In assessing the ability to benefit from treatment, chronological age is less important than other factors concerned with the biological ageing process and the presence of associated disease.1

Any rationing because of limitation of health resources should be on the basis of assessed individual physiological ability to benefit, not on the basis of age any more than on sex or skin colour.2

Summary points

The rates of use of potentially life saving and life enhancing investigations and interventions decline as patients get older

Ageism in clinical medicine and health policy reflects the ageism evident in wider society

A wide ranging approach is required to tackle ageism in medicine; clinical guidelines should be improved, more specific monitoring of health care should be introduced, and educational and research initiatives should be developed

Older people could be empowered to influence the choice and standard of health care offered

Legislation may be required to end ageism in society

Evidence

The ageing of the population is one of the major challenges facing health services. The growing number of older people is likely to place increasing demands on health services for access to effective health technology in cases in which this can enhance the quality, not just the quantity, of life. There is some evidence that age has been used as a criterion in allocating health care3 and in inviting participation in screening programmes.4 However, the idea that a patient's age may be used as an explicit basis for priority setting has rarely been acknowledged.5

Cardiovascular diseases are a common cause of death and disability among older people, and the use of appropriate health technologies for diagnosis and treatmentis expensive. Despite the slightly higher risks of perioperative mortality and morbidity in older people, if they are selected appropriately they are likely to gain substantial health benefits from cardiological interventions.1,6,7 Ironically, although cardiac surgeons are increasingly operating on people aged 75 and older, analyses in Europe and the United States which examined both the rates and types of interventions used indicate that age biases exist in cardiology. The argument presented here—that ageism exists in health care—uses research on the equity of access to cardiological services.

Rates of potentially life saving and life enhancing cardiological interventions, such as revascularisation, have been reported to vary widely by country, ethnic group, place of residence, economic activity (that is, whether someone is in paid employment), sex, and age.8–13 Higher rates of intervention occur among younger people than among older people, despite the prevalence of cardiovascular disease being considerably higher among the latter group. Older people, and older women in particular, are less likely to receive appropriate cardiological investigations—from echocardiography to measuring cholesterol concentrations.14 Older people are more likely to have more severe disease and to be treated medically rather than surgically,15,16 and they are less likely to receive the most effective treatment after acute myocardial infarction.17 They receive thrombolytic treatment less often than younger people, even in the absence of contraindications.18–20 The effects of age on access to health care occur independently of sex.

Reasons

It is unknown whether implicitly age based referrals, investigations, and treatment policies in primary care and secondary care reflect rationing criteria or prejudices against older people. The consequences of both rationing and prejudices are that younger people take priority over older people.5 In relation to rationing, shortages of resources might lead to discrimination against older patients on the basis of the belief that they are more expensive to treat (for example, they may need longer to recover after surgery) or that they have a shorter life expectancy and therefore resources should be diverted to younger people who would be expected to live longer. Age is frequently discussed as a criteria for rationing. It is defended on the grounds that older people have had their “fair innings.”21 It is rejected on the grounds that decision making on the basis of sociodemographic characteristics, without reference to relevant comorbidity and ability to benefit, is unethical.22,23

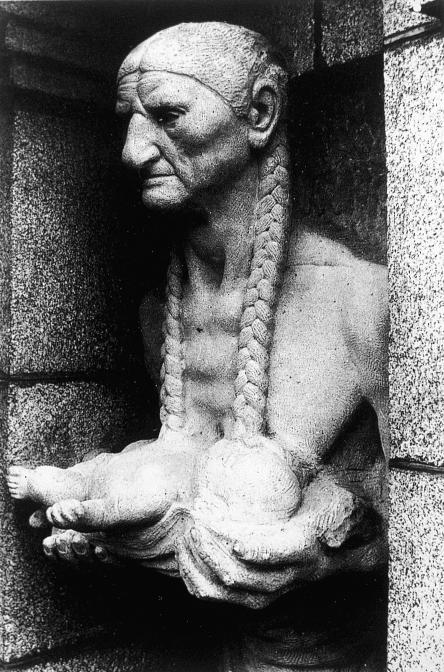

Age biases are likely to be a consequence of different values being attributed to different social groups and to age stereotyping. Any ageism in medicine is simply a reflection of ageist attitudes that exist in the wider society, where youth is given priority over age.24,25 Older people are frequently portrayed as frail and haggard, contrasting strongly with images of children (fig 1). However, advertisers increasingly look to the futureand are adept at shaking up society's common stereotypes of age (fig 2).

Figure 1.

New Born by Jacob Epstein (from the former BMA building, the Strand). Reproduced with the permission of Kitty Godley, copyright estate of the artist

Figure 2.

ALON REININGER/CONTACT/COLORIFIC!

Some advertisers have recently used images like this one to sell energy drinks

Ageism in medicine may be partly a consequence of a lack of awareness of the evidence based literature on the treatment of older people. Variations in clinical decisions made on the basis of the age of the patient might also be caused by the differing thresholds for intervention that exist when a healthcare professional is faced with clinical uncertainty; these variations might also reflect preferences for selecting low risk, rather than high risk, patients to undergo interventions. That variations in treatment exist is unsurprising given that people aged 65 and older, and certainly those who are 75 and older (most of whom are women), have been largely excluded from major clinical trials. They are therefore significantly underrepresented in the evidence base used to determine clinical effectiveness.19,26,27 Investigators have traditionally used age limits as cut off points when recruiting patients into clinical trials to minimise analytical problems caused by factors such as comorbidity and an increased risk of loss to long term follow up caused by death. Most of the evidence on the clinical effectiveness of treatments for older people is based on a few smaller trials and cohort studies. This research bias may have led clinicians to be cautious in treating very old people, especially older women.

The collective consequences of these biases, whatever their causes, is that older people may not be treated equitably when it comes to allocating healthcare resources.Moreover, current practice is not necessarily the most efficient for health or social services. Clinical delay or denying older people the benefit of certain interventions may lead to greater spending on “maintenance” services such as those provided by district nurses, home helps, and “meals on wheels” programmes. The provision of more invasive treatments could be cost effective if they enabled people to function independently.

Solutions

Patients are not usually in a position to assess the appropriateness of the care they receive, and they trust their doctors to act in their best interests. Ageism in medicine needs to be tackled to preserve—or recapture—this trust within an ageing population. Clinicians, managers, and educationalists need to work together to eradicate it. A wide ranging approach is required if equity in the provision of health care by age is to be ensured.

Clinical guidelines should be developed and regularly updated to enable clinicians to make more informed decisions about treating older people, and access to investigations and treatments should be monitored centrally.28 These developments may be given impetus in the United Kingdom by the recently established National Institute for Clinical Excellence and internationally by the emphasis on clinical governance. Hospital league tables of intervention rates by the age and sex of the patient and standardised for the age and sex distribution in the population could be published. Educational efforts are needed to increase the awareness of the public and professionals that age stereotyping and ageist attitudes are not acceptable and that ageist stances in clinical and health policy decision making are unethical. The major medical bodies that fund research now specify that exclusions from clinical trials on the grounds of age alone are no longer acceptable without justification. Research organisations should also encourage those who design clinical trials to include large numbers of older people in an effort to redress the balance of evidence on clinical outcomes. Methodological research should be funded to assess the implications of ending the traditional exclusions from clinical trials that have been made on the basis of a participant's age (for example, to determine the scale of the increase in sample size required to control for multiple comorbidity and to allow for attrition due to increased numbers of deaths at follow up).

We should empower older people to influence the choices and standards of treatments offered. This could be achieved by publicly disseminating information on treatment alternatives and investigating patients' preferences for treatments. Finally, recourse to the law to eradicate ageist attitudes and practices could be considered through the enactment of an age discrimination act (MM Rivlin, personal communication, 1999). Older people would then be less likely to suffer discrimination, particularly if discrimination perpetrated to save money became illegal, as it is under the Race Relations Act. It is only by eliminating ageism in clinical research and practice that valid information on clinical effectiveness can be established and the necessary level of funding for health services can be identified.29

Acknowledgments

I thank Dorothy McKee and Joy Windsor for their comments on earlier drafts of this manuscript, Michael Rivlin for his helpful thoughts, and Graham Ward of Phaidon Press picture library archive for advice.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Royal College of Physicians. Cardiological intervention in elderly patients. A report of a working group of the Royal College of Physicians. London: RCP; 1991. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carnegie Institute. Life, work and livelihood in the third age: final report of the Carnegie Inquiry into the Third Age. Dunfermline: Carnegie United Kingdom Trust; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Audit Commission. Dear to our hearts? Commissioning services for the treatment and prevention of coronary heart disease. London: HMSO; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sutton GC. Will you still need me, will you still screen me, when I'm past 64? BMJ. 1997;315:1032–1033. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7115.1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coast J, Donovan J. Conflict, complexity and confusion: the context for priority setting. In: Coast J, Donovan J, Frankel S, editors. Priority setting: the health care debate. Chichester: John Wiley; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gilbert T, Orr W, Banning AP. Surgery for aortic stenosis in severely symptomatic patients older than 80 years: experience in a single UK centre. Heart. 1999;82:138–142. doi: 10.1136/hrt.82.2.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheitlin MD. Coronary artery bypass surgery in the elderly. Clin Geriatr Med. 1996;12:195–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yusuf S, Flather M, Pogue J, Hunt D, Varigos J, Piegas L, et al. Variations between countries in invasive procedures and outcomes in patients with suspected unstable angina or myocardial infarction without initial ST elevation: OASIS (organisation to assess strategies for ischaemic syndromes) registry investigators. Lancet. 1998;352:507–514. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)11162-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peterson ED, Shaw LK, Delong ER, Pryor DB, Califf RM, Mark DB. Racial variation in the use of coronary-revascularisation procedures. Are the differences real? Do they matter? N Engl J Med. 1997;336:480–486. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199702133360706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Black N, Langham S, Pettigrew M. Coronary revascularisation: why do rates vary geographically in the UK? J Epidemiol Commun Health. 1995;49:408–412. doi: 10.1136/jech.49.4.408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gaffney B, Kee F. Are the economically active more deserving? Br Heart J. 1995;73:385–389. doi: 10.1136/hrt.73.4.385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Black N, Langham S, Pettigrew M. Trends in the age and sex of patients undergoing revascularisation in the UK. Br Heart J. 1994;72:317–329. doi: 10.1136/hrt.72.4.317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pilote L, Miller DP, Califf RM, Rao JS, Weaver WD, Topol EJ. Determinants of the use of coronary angioplasty and revascularisation after thrombolysis for acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1198–1205. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199610173351606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bowling A, Ricciardi G, La Torre G, Boccia S, McKee D, McClay M, et al. The effect of age on the treatment and referral of older people with cardiovascular disease [abstract] J Epidemiol Commun Health. 1999;53:658. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stone PH, Thompson B, Anderson HV, Kronenberg MW, Gibson RS, Rogers WJ, et al. Influence of race, sex and age on management of unstable angina and non-Q-wave myocardial infarction. The TIMI III registry. JAMA. 1996;275:1104–1112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wenger NK. Coronary heart disease: an older woman's major health risk. BMJ. 1997;315:1085–1090. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7115.1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McLaughlin TJ, Soumerai SB, Willison DJ, Gurwitz JH, Borbas C, Guadagnoli E, et al. Adherence to national guidelines for drug treatment of suspected acute myocardial infarction. Evidence for undertreatment in women and the elderly. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:799–805. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.European Secondary Prevention Study Group. Translation of clinical trials into practice: a European population-based study of the use of thrombolysis for acute myocardial infarction. Lancet. 1996;347:1203–1207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McMechan SR, Adgey AAJ. Age related outcome in acute myocardial infarction. BMJ. 1998;317:1334–1335. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7169.1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dudley NJ, Burns E. The influence of age on policies for admission and thrombolysis in coronary care units in the United Kingdom. Age Ageing. 1992;21:95–98. doi: 10.1093/ageing/21.2.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williams A. Rationing health care by age: the case for. BMJ. 1997;314:820–822. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7083.820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grimley Evans J. Rationing health care by age: the case against. BMJ. 1997;314:822–825. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7083.820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rivlin MM. Protecting elderly people: flaws in ageist arguments. BMJ. 1995;310:1179–1182. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6988.1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bowling A. What people say about prioritising health services. London: King's Fund; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bowling A. Healthcare rationing: the public's debate. BMJ. 1996;312:670–674. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7032.670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bugeja G, Kumar A, Banerjee AK. Exclusion of elderly people from clinical research: a descriptive study of published reports. BMJ. 1997;315:1059. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7115.1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gurwitz JH, Col NF, Avorn J. The exclusion of the elderly and women from clinical trials in acute myocardial infarction. JAMA. 1992;268:1417–1422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sculpher MJ, Pettigrew M, Kelland JL, Elliott RA, Holdright DR, Buxton MJ. Resource allocation for chronic stable angina: a systematic review of the effectiveness, costs and cost-effectiveness of alternative interventions. Health Technol Assess. 1998;2:1–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Elder AT, Shaw TRD, Turnbull CM, Starkey IR. Elderly and younger patients selected to undergo coronary angiography. BMJ. 1991;303:950–953. doi: 10.1136/bmj.303.6808.950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]