Let me die a young man's death, not a clean and inbetween the sheets holywater death not a famous-last-words peaceful out of breath death. Roger McGough1

We all want to go quickly when the time comes—but most of us linger and more of us will become enmeshed with health services before we die. Most of us will see our 85th birthday, but unfortunately for a quarter of us, that will be through the haze of a dementia syndrome or some other chronic disease or disability.

Summary points

Increasing subspecialisation in medicine produces doctors who are unable to deal with the complexity of multiple pathology found in most older people

Undergraduate medical education reforms are forcing specific training in geriatric medicine out of the curriculum

Postgraduate education requires reorganisation, including mandatory attachments in geriatric medicine, to ensure that all doctors are capable of managing elderly patients appropriately

Globalisation of employment for doctors and nurses means that curriculums in developing countries may not meet the needs of those who practise in industrialised countries

Traditional medical careers are changing so that many doctors will need to gain new skills and consider career changes over the course of their lives

Demographic change and medical training

Industrialised countries will see a massive increase in the numbers of both young old (age 60-74) and old old (age 75 or more) over the next two decades. The postwar baby boom generation will become the young pensioners in 2020 and the numbers of very elderly people will also increase substantially from current levels. In Great Britain, the number of people aged 85 years and over has increased by 25% over seven years.2 Populations in developing countries are ageing more rapidly than those in the developed world, and this has implications for medical training in these places. The growing globalisation of employment for many health professionals, particularly nurses, means that demographic shifts have implications for training of health professionals world wide.

With an ageing population come increases in chronic and degenerative diseases and the problems of multiple pathology. It is multiple pathologythat makes current medical training so likely to lead toinappropriate and poor quality care. Increasing specialisation carries the danger of a failure to see the whole patient. Demands to keep up to date in ever smaller areas of medical care drive out time for developing and maintaining more general skills. I overheard a colleague telling a local general practitioner that he no longer dealt with jaundiced patients but was confining himself to the hepatocyte.

The appropriately trained specialist

Consider this 2020 vision of the teaching hospital. The consultant cardiologist, Professor Gupta, enters the ward with her team. She sits down in the ward day room with other members of the interdisciplinary team. The nurse explains that Mr A, a 79 year old man who was admitted two days ago with severe chest pain, is now stable. He is very worried about his dog, which was in the house when the ambulance came. The nurse says that Mr A also seems to be a bit confused and has been incontinent of urine several times since admission. Professor Gupta asks the house officer what Mr A's mental test score was on admission, what the general practitioner said about medical history, and about medication and social circumstances. The house officer explains that the patient was disorientated in time and place. He put this down to left ventricular failure and hypoxia. The general practitioner told him that Mr A had been very depressed since the death of his wife from a heart attack two years ago. He has been taking amitryptiline and this had probably caused the faecal impaction and urinary incontinence that the district nurse was managing. A neighbour was looking after the dog and the general practitioner said he would come in to say hello to Mr A today. The social work assistant was planning to see Mr A to review his services and to arrange some extra support from the early discharge team. “If only....”

The ageing population is placing all doctors (except paediatricians) in the front line of geriatric medicine. Ageing and sickness go together, and the consequence is that hospitals are filled with elderly people who require a very different approach from the traditional inpatient or primary care services.

Undergraduate medical education

Health care for elderly people requires interdisciplinary team work, as no single member of the team is capable of providing all the skills and knowledge needed for the care of elderly patients. We know only too well what is required, and we have known for a very long time.3 In 1970 the British Medical Students' Association called for a joint core curriculum for all health professionals which would foster better understanding of and respect for each other's roles. Our elders knew better then and it never happened.

The reorganisation of London teaching hospitals over the past five years, following the publication of the Tomlinson report, has not resulted in new alliances with the former polytechnics, schools of nursing and therapies to produce a health sciences campus. Deans and vice chancellors have failed to realise that the pursuit of “excellence” through a retreat into basic science is more likely to result in stagnation of education and more grossly ill-trained doctors than ever before. Similar patterns are arising in most of the provincial medical schools, although the recent announcement of new medical schools4 and allocation of additional medical school places to universities that proposed novel alliances with new universities shows the levers that are required to achieve change.

The implementation of the General Medical Council's reforms for undergraduate education have put the process and setting of learning at centre stage—small group, problem based learning in community and primary care settings is the preferred model.5 The efforts put into educational process should be paralleled by similar effort in determining content through assessments of knowledge and skills required by a newly qualified doctor.6

The move from a proliferation of small, underresourced academic departments—typical of many departments of geriatric medicine—to much larger groupings of academic staff in research focused groups serves research well. It is less clear how well such broad groupings will serve elderly patients. As one medical student reviewing a proposal for a third edition of the textbook I co-write said:“The new course does not cover geriatric medicine ... but general medical and surgical teaching is not yet good enough on focusing on the problems in old age.”7The role of academic departments of geriatric medicine to provide leadership and a focus for teaching will remain; the departments may not. The traditional power relationships in medical schools make it likely that considerable imagination and strong partnerships with community and primary care teachers will be required by geriatricians and psychogeriatricians to maintain sufficient input into new curriculums.8 Elderly patients have served as efficient vehicles for learning the examination of common physical signs—their histories were too long for the attention span of the average medic—for a generation of doctors. We now need to ensure that current doctors know how to assess elderly patients and what to do about the common problems of incontinence, immobility, instability, insanity, and iatrogenesis, among other issues (box). Specialists in health care for elderly people know how do to this.9–11

Undergraduate curriculum in geriatric medicine: topics and examples of learning experiences

Talking to elderly patients: taking time, use of communication aids, and short repeated interviews

Understanding what it is like to be an elderly person: “instant” ageing games where students experience painful feet, visual and hearing impairment, and immobility

Interdisciplinary team work: seeing how different professionals assess and treat patients, gaining respect for their contribution, and attending team meetings

Presentation of disease in elderly patients: recognising non-specific presentations of common diseases

Ageism among doctors: realising that “social” problems are usually poorly assessed medical problems

Prescribing in elderly patients: examining and critically appraising prescription charts

Rehabilitation: taking part in the processes of reablement and resettlement in patients with acute and chronic diseases

Care in the community: visit elderly people at home and in residential or nursing homes and understand how health and social services are organised

Postgraduate medical training

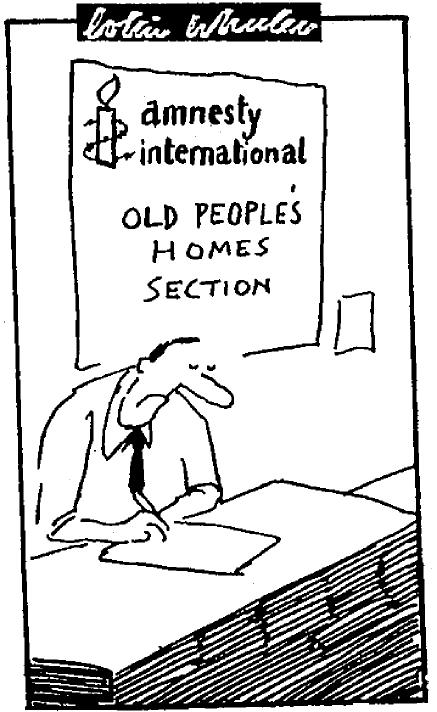

Vocational training schemes, specialist registrar training programmes, and continuing professional development all require new thinking to meet the reasonable demands of elderly patients. The energy that has gone into defining the skills required of preregistration house officers has not yet been applied to those of us further on in our careers.6 Postgraduate deans are silent on the matter. But why not require all general practitioners and hospital specialists (except the paediatricians) to have six months' experience in health care for elderly people? Mandatory attachments would not be sufficient to reduce the ageism and negativity of some doctors, but they would help many doctors to improve their history taking, examination, and management skills to a safe level.

A meeting in May 1999 on global perspectives in healthcare and clinical training, jointly organised by the Royal Colleges of Physicians and Surgeons, discussed topics as diverse as molecular medicine, hepatocellular carcinoma, and herbal medicine. Ageing was never mentioned. The blindness of our royal colleges, our medical schools, and our postgraduate deaneries must be challenged.

Globalisation of health care has resulted in doctors and nurses trained in one country seeking, and finding, work in another. The “needs based” undergraduate and postgraduate curriculums in developing countries do not include study of health care for older people. In many of these countries, substantially more doctors and nurses are trained than are required for local needs or can be afforded. The human resource potential currently lost to individuals and society might be captured by reorientation of our educational programmes and a deliberate policy of training for export. The potential for asset stripping of poorer countries to supply the needs of industrialised ones remains a dilemma.

Doctors, ourselves

We are all growing older, and if current employment patterns apply to medicine, many of us will need to consider second or even third careers. The traditional medical career from general practitioner principal or consultant from early 30s to retirement at 65 is likely to change dramatically. Increasingly, those who can are opting for early retirement, and all of us are at risk of redundancy in our early 50s. We have only just begun to think about the need for increasing the range of skills doctors possess throughout the course of their careers. However, much of continuing professional development does not consider new directions in medical and other careers but is conducted to ensure that we all get sufficient credits to maintain the status quo.

Ultimately, the narrow focus that dominates medicine from the undergraduate phase to the end our professional lives will be our undoing. We are guilty of providing a poor service to our elderly patients, and we will be doing ourselves a disservice in our own old age.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.McGough R. The Mersey sound. Harmondsworth: Penguin; 1967. Let me die a young man's death; p. 91. . (Penguin modern poets, vol 10.) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ebrahim S, Kalache A. Epidemiology in old age. London: BMJ Publications; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Young A. There is no such thing as geriatric medicine, and it's here to stay. Lancet. 1989;ii:263–265. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)90440-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brindle D. Three new schools for doctors aimed at broader social range. Guardian 1999 June 23.

- 5.Harden RM, Davis MH, Crosby JR. The new Dundee medical curriculum: a whole that is greater than the sum of the parts. Med Educ. 1997;31:264–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1997.tb02923.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bax ND, Godfrey J. Identifying core skills for the medical curriculum. Med Educ. 1997;31:347–351. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.1997.00676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bennett G, Ebrahim S. London: Arnold; 1995. Essentials of health care in old age. 2nd ed. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turpie ID, Blumberg P. Integrating geriatrics into medical school through problem-based learning. Gerontol Geriatr Educ. 1995;15:29–43. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dickinson EJ, Young A. Framework for medical assessment of functional performance. Lancet. 1990;335:778–779. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)90881-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lorraine V, Allen S, Lockett A, Rutledge CM. Sensitizing students to functional limitations in the elderly: an aging simulation. Family Med. 1998;30:15–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.International Review Syllabus in Geriatrics. www.healthandage.com/fphysi.htm (accessed 25 October 1999).