Abstract

Retroviral RNA molecules are plus, or sense in polarity, equivalent to mRNA. During reverse transcription, the first strand of the DNA molecule synthesized is minus-strand DNA. After the minus strand is polymerized, the plus-strand DNA is synthesized using the minus-strand DNA as the template. In this study, a helper cell line that contains two proviruses with two different mutated gfp genes was constructed. Recombination between the two frameshift mutant genes resulted in a functional gfp. If recombination occurs during minus-strand DNA synthesis, the plus-strand DNA will also contain the functional sequence. After the cell divides, all of its offspring will be green. However, if recombination occurs during plus-strand DNA synthesis, then only the plus-strand DNA will contain the wild-type gfp sequence and the minus-strand DNA will still carry the frameshift mutation. The double-stranded DNA containing this mismatch was subsequently integrated into the host chromosomal DNA of D17 cells, which were unable to repair the majority of mismatches within the retroviral double-strand DNA. After the cell divided, one daughter cell contained the wild-type gfp sequence and the other daughter cell contained the frameshift mutation in the gfp sequence. Under fluorescence microscopy, half the cells in the offspring were green and the other half of the cells were colorless or clear. Thus, we demonstrated that more than 98%, if not all, retroviral recombinations occurred during minus-strand DNA synthesis.

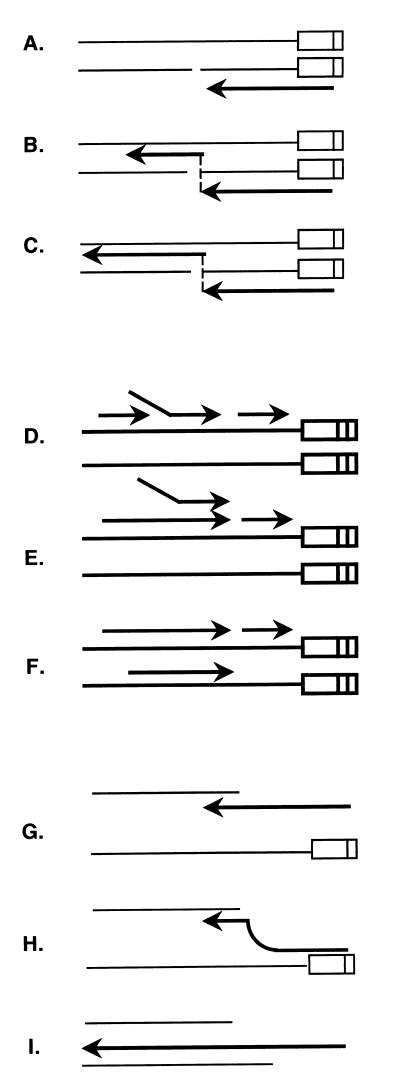

Recombinations in retroviral genes play important roles in retroviral carcinogenesis and in the AIDS epidemic. Two plausible models for retrovirus recombination were first proposed 16 years ago. A third model has recently been proposed. However, none of these models have been critically tested. The first model (Fig. 1A to C) proposed that recombination occurred during minus-strand synthesis using RNA as the template (7). This model proposed that retroviral genomes contain considerable numbers of breaks within the RNA molecule and that when reverse transcriptase encounters such breaks, it switches to the homologous sequence on the other RNA molecule and continues synthesis. This model is called the forced-copy-choice model. The second model (Fig. 1D to F) proposed that recombination occurs during plus-strand DNA synthesis (15, 16). This model proposed that two minus-strand DNAs are made in one virion using both RNA templates (retrovirus packages two RNA molecules in each virion). Since plus-strand DNA synthesis is initially discontinuous, a fragment of product DNA might be displaced by continuous DNA synthesis. The displaced DNA fragment may then hybridize to the minus-strand DNA synthesized from the other molecule of viral RNA used as the template. This model is called the plus-strand replacement model. The third model differs from the original copy choice models because it does not require preexisting breaks in the RNA (6) (Fig. 1G to I). Since reverse transcriptase has a relatively low processivity and because the RNA template is degraded approximately 18 nucleotides from the point of DNA synthesis, it is proposed that an extended single-stranded DNA molecule is left tailing behind. This DNA molecule is free to form a hybrid duplex with another RNA molecule. If the reverse transcriptase molecule detaches from the template, it is likely that the short (18-bp) hybrid with the original template will be displaced by branch migration of the second RNA and that this RNA molecule will then become the template for continued synthesis. This model is called the minus-strand replacement model.

FIG. 1.

Models of retroviral recominations. The light lines represent RNA molecules, and the heavy lines represent DNA molecules. (A to C) Model of forced copy choice for retroviral recombination. This model proposes that retroviral genomes contain breaks within the RNA molecule (A) and that when reverse transcriptase encounters such breaks, it switches to the homologous sequence on the other genome (B) and continues minus-strand DNA synthesis (C). (D to F) Model of strand displacement-assimilation for retroviral recombination. This model proposes that two minus-strand DNAs are made within one virion (D). Since plus-strand DNA synthesis is initially discontinuous, a fragment of product DNA might be displaced by continuous DNA synthesis (E). The displaced DNA fragment may then hybridize to the other minus-strand DNA (F). (G to I) Model of minus-strand exchange for retroviral recombination. An extended single-stranded DNA molecule is left tailing behind during synthesis of minus-strand DNA (G). This DNA molecule forms a hybrid duplex with another RNA molecule (H). The reverse transcriptase molecule detaches from the template and is displaced by the second RNA (I).

Data have demonstrated that poly(A) sequences exist in some recombinants of one naturally occurring acute oncogenic virus (14) and in three other experimental systems, including the one we have described previously (22, 25, 28). The poly(A) tracts exist only on the RNA molecules and not on the minus-strand DNA molecules during reverse transcription, since the minus-strand strong stop DNA jumps to the R region [upstream of the poly(A) tract] to continue synthesis of minus-strand DNA. Therefore, some, if not all, recombination events should use an RNA molecule as the template. Since minus-strand DNA synthesis uses RNA as a template, these results suggest that some retroviral recombinations occur during minus-strand DNA synthesis.

The retroviral RNA molecules are positive sense in polarity, equivalent to mRNA. During reverse transcription, the first strand of DNA synthesized is minus in polarity since it is synthesized from the positive-sense RNA molecule, which is used as the template. The minus-strand DNA is complementary to the plus or sense viral genomic RNA. After the minus-strand DNA is polymerized, the plus-strand DNA is synthesized using the minus-strand DNA as the template. By this rationale, if a change results from recombination that occurs during minus-strand DNA synthesis, the plus-strand DNA would also contain this change, because during synthesis of the plus-strand DNA, the minus-strand DNA is used as the template. However, if changes occurs during plus-strand DNA synthesis, the double-stranded DNA would contain a mismatch. A mismatch within retroviral double-stranded DNA can also be introduced by a preexisting mutation within the primer binding site (PBS) of the positive-sense viral RNA genome (3, 8). The PBS is the binding site for a host tRNA within the viral RNA molecule. The PBS is 18 bases in length in Moloney leukemia virus (MLV). The 18-base sequence is reverse transcribed into a minus-strand DNA using the viral RNA genome as the template, while the plus-strand DNA is synthesized using the host tRNA 3′ end as the template. If there is a preexisting mutation within this PBS on the viral RNA molecule, the minus-strand DNA contains the mutation while the plus strand remains the wild type (wt). Therefore, the double-stranded DNA should contain a mismatch within the PBS.

Retroviral double-stranded DNA is then integrated into the cellular chromosome DNA to form a provirus. Most cells contain a system to repair different types of mismatches. Some cell lines, such as the HCT 116 cell line, contain defects in their DNA repair systems and are incapable of repairing mismatches (10, 20). To date it is not clear if the mismatch in the provirus can be repaired by the host cellular DNA repair system. If the target cells does not repair the mismatch before an infected cell divides, one daughter cell will contain this mutation while the other daughter cell will not contain this mutation. Therefore, the offspring of the infected cells should carry two different proviruses. However, in the host cell, these two different proviruses would be integrated into the same site of the host chromosome if the integration resulted from a single event. This report demonstrates that D17 cells (target cells) are unable to repair the majority of mismatches within the retroviral double-stranded DNA. This property of D17 cells, therefore, is useful for determining at which step(s) retroviral recombinations occur.

Previous studies that were designed to determine the recombination rate of a retrovirus have used selectable genes and cell culture systems (12, 28). In this report, drug selection markers have been exchanged for an unselected color reporter gene, gfp (green fluorescent protein) (5). Cells containing the wt gfp reporter gene appear green under fluorescence microscopy, while cells with a mutant gfp appear colorless or clear (24, 27). A helper cell containing two proviruses that encoded two mutated gfp genes was constructed. We reasoned that recombination between the two mutations would produce a functional gfp gene. Because the plus-strand DNA is synthesized from the minus-strand DNA template—the recombination occurs during minus-strand DNA synthesis—the plus-strand DNA will also carry the functional gfp sequence. After the cell divides, all the offspring cells will be green under a fluorescence microscope. However, if the recombination occurs during plus-strand DNA synthesis, only the plus-strand DNA will contain the functional gfp sequence and the minus-strand DNA will contain the mutated gfp. The double-stranded DNA, which contains a mismatch, integrates into the host chromosomal DNA to form a provirus. Because D17 cells are unable to repair this mismatch, after the cell divides into two daughter cells, one of the daughter cells will encode wt gfp and the other daughter cell will encode a mutated gfp. Growth of the offspring of these two daughter cells will produce a colony. Under the fluorescence microscope, this colony should be a mixture of green and clear cells.

However, a colony of a mixture of green and clear cells is not necessarily a result from a recombination (one event) occurring during plus-strand DNA synthesis. Another possibility for the formation of a mixed colony is an infection with two viruses of two daughter cells that have just undergone division from one cell (or two cells that were plated together on a dish) (two separate events). One virus is a parent-type virus (clear), and the other virus is a recombinant formed during minus-strand DNA synthesis (green). If a colony of cells results from two infection events, the resulting colony should be a mixture of two different cells, each of which contains a different provirus resulting from an independent integration event. However, in this scenario these two proviruses will have integrated into two different sites. If a colony of mixed cells results from a recombination occurring during plus-strand DNA synthesis, however, the provirus in the green cells should be integrated into the same site as the clear cells in their mixed colony. Using this rationale, we demonstrate that more than 98%, if not all, of retroviral recombinations occur during minus-strand DNA synthesis. In other words, the model of copy choice or minus-strand displacement is the mechanism of most, if not all, retroviral recombination events.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Nomenclature.

Plasmids are designated, for example pJZ425 and pJZ468; viruses made from these plasmids are designated, for example, JZ425 and JZ468.

Vector constructions.

All recombinant techniques were carried out according to conventional procedures (23). All vector sequences are available upon request.

(i) Construction of pLT2.

To construct a retroviral vector that contains one base mutation in its PBS region, three fragments were ligated. The first fragment was derived from pLN (19) and contained two MLV long terminal repeats (LTRs) and a neomycin resistance gene (neo). pLN was digested with PshAI and BstEII. PshAI digested 17 bp upstream of the PBS, while BstEII digested within the package signal, 537 bp downstream of the PBS. The second fragment was a double-stranded DNA created by annealing two artificially synthesized oligonucleotides. The first oligonucleotide was GGGTCTTTCATTTGGGGGCTCGc, while the second oligonucleotide was CCGGgCGAGCCCCCAAATGAAAGACCC (the lowercase letters represent the nucleotides that are different from those of the wt PBS sequence). The 5′ end of this DNA was blunt and compatible with the PshAI-digested DNA fragment. The 3′ double-stranded DNA contained a sticky end, which was identical to the sticky end formed by digestion with XmaI. This double-stranded DNA was designated the PshAI-XmaI fragment. The third fragment was also derived from pLN. Sequences of pLN were amplified by PCR using two primers. The first primer (GGGGGCTCGcCCGGGATTT) was located at the PBS; however, the thymidine (T) within the PBS at position 744 was changed to cytosine (C) so that the mutated PBS would be digested with XmaI (cCCGGG) (underlined). The amplified fragment was digested with XmaI and BstEII. The BstEII-PshAI fragment isolated from pLN, the double-stranded DNA artificially synthesized with PshAI and XmaI and the XmaI- and BstEII-digested PCR-amplified fragment were ligated. The resulting plasmid was designated pLT2, which was identical to pLN except that the T at position 744 was changed to C so that this plasmid would contain an additional SmaI site at the PBS. (SmaI recognizes the same CCCGGG as XmaI does, except that the SmaI-cut fragment is blunt ended while the XmaI-cut fragment forms a sticky end.)

(ii) Construction of a retroviral vector with deletion of the downstream PBS.

The EcoRI fragment which contained the MLV 5′ LTR was cloned into pSP73 (Promega, Madison, Wis.). To delete the downstream PBS, the MLV vector was amplified by PCR using two primers. The first primer (TAGAACCAGATCTGATATCATC) was located on pSP73, and the second primer (GACGAGgtCgacAATGAAAGACCCCCGTCGTGGGT) was located at the U5 region of the 3′ LTR. The first six nucleotides (CCCCCA) of the PBS region were changed to (gtCgac), so that the amplified fragment could be digested with SalI. The amplified fragment was digested with BglII and SalI, and this BglII-SalI fragment did not contain the downstream PBS.

(iii) Construction of a retroviral vector which contains an additional SmaI site at its PBS and deletes the downstream PBS.

The pLN plasmid contains two MLV LTRs and a neo gene. Plasmid pLT5 is similar to pLN except that pLT5 contains a T→C transition at the PBS and the PBS downstream of the 3′ LTR is deleted (Fig. 2A). Plasmid pLT5 was constructed by ligations of five fragments from three vectors. The five fragments are as follows: the SalI-EcoRI fragment (positions 5324 to 2232), which contains the pUC18 (26) backbone; the EcoRI-AscI fragment of pLN (positions 2233 to 2816), which contains half of the 5′ LTR; the AscI-BstEII fragment (positions 2817 to 3519) of pLT2, which contains the other half of the 5′ LTR and a mutation within the PBS region; the BstEII-XbaI fragment (positions 3520 to 5027) from pLN, which contains the neo gene and half of the 3′ LTR; and the XbaI-SalI fragment of pLN (positions 5028 to 5323), which contains the second part of the 3′ LTR and the deleted downstream PBS region.

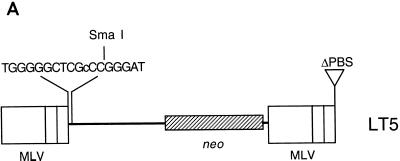

FIG. 2.

(A) Structure of a retrovirus vector which contains a transition mutation on its PBS. The retroviral vector LT5 contains the neo gene between two MLV LTRs. Retroviral replication uses host tRNA as its primer. This 18-base PBS (GGGCTCGTCCGGGAT) is complementary to the tRNAPro 3′ end on the acceptor arm. The T at the 11th nucleotide (underlined) was changed to C so that the 11th to 16th nucleotides within the PBS region could be digested with SmaI (cCCGGG) (the lowercase letter represents the nucleotide that is different from the nucleotide in the wt PBS sequence.) The PBS downstream from the 3′ LTR was deleted. The 18-base sequence is reverse transcribed into a minus-strand DNA using the viral RNA genome as the template; the plus-strand DNA is synthesized using the host tRNA 3′ end as the template. Because of this preexisting mutation within this PBS region on the viral RNA molecule, the minus-strand DNA contains the mutation (i.e., C) while the plus-strand sequence remains wt (i.e., T). Therefore, the double-stranded DNA should contain a mismatch (C or T) within the PBS region. (B) Electrophoresis of the PCR-amplified fragment of the PBS region of DNA isolated from D17 cells infected with LT5. The cellular DNA of each Neor colony infected with LT5 was amplified by PCR, followed by digestion with SmaI. After digestion, the amplified parental fragment was cut into two fragments, 686 and 207 bp in length. If the amplified mutant PBS fragments contained an additional SmaI site within the PBS region and this amplified fragment was digested with SmaI, there would be three fragments, which would be 558, 207, and 128 bp in length. Lane 1, SmaI-digested amplified DNA fragments from plasmid pLT5; lane 2, SmaI-digested amplified DNA fragments from plasmid pLN; lanes 3 to 26, SmaI-digested amplified DNA fragments from DNA isolated from individual Neor colonies infected with pLT5.

(iv) Introduction of restriction enzyme sites within the gfp gene.

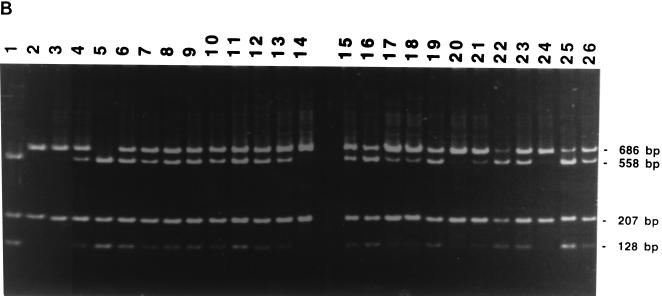

The gfp gene was isolated from the jellyfish Aequorea victoria (wt GFP; Clontech, Palo Alto, Calif.). The wt gfp open reading frame contains an NcoI site at the 5′ end and a BstBI site at the 3′ end (Fig. 3A). Three amino acids between the two sites have been changed so that the gfp gene emits brighter light. In addition, wt gfp has also been engineered to contain silent mutations in all of its amino acid codons to fit the human codon usage preference in order to increase its translational efficiency (Clontech). In this study, the gfp gene containing these silent mutations is designated h-gfp (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 3.

Structures of retroviral vectors used for determining in which step(s) the recombinations in retroviral replication occur. (A) wt gfp gene. The gfp gene was isolated from the jellyfish A. victoria, which contains an NcoI site at the 5′ end and a BstBI site at the 3′ end. (B) h-gfp gene. wt gfp has also been engineered to contain silent mutations in all of its amino acid codons to fit the human codon usage preference in order to increase the translational efficiency and is designated h-gfp. (C) Chimeric gfp-BstBI gene. The gfp-BstBI gene contains a BstBI site, which was constructed by PCR with the h-gfp sequence to allow the construction of an h-gfp–wt-gfp chimeric gene. The 5′ end upstream of the BstBI site remains the h-gfp sequence. (D) Chimeric gfp-NcoI gene. The gfp-NcoI gene contains an NcoI site in wt gfp, and the construction in the h-gfp sequence upstream of the NcoI site was replaced with the wt gfp gene to produce this chimeric gene. (E) Structure of the retroviral vector pJZ425. pJZ425 contains a selectable marker (hyg) and an unselectable color reporter gene, gfp-BstBI. The gfp gene is transcriptionally expressed from the MLV 5′ LTR (containing the promoter and enhancer), and the selectable gene (hyg) is expressed from an IRES. A frameshift mutation is at the 3′ end of the gfp gene. (F) Structure of the retroviral vector pJZ468. pJZ468 is similar to pJZ425; however, the neo gene is replaced with the hyg gene and a frameshift mutation is at the 5′ end of the gfp-NcoI gene.

h-gfp was mutated by PCR to create a BstBI site within the wt gfp, and the sequence downstream of the BstBI site was replaced with the wt gfp gene. The 5′ end upstream of the BstBI site was maintained as the h-gfp sequence. This resulted in the construction of the first chimeric gfp gene, which we have designated gfp-BstBI (Fig. 3C). h-gfp was also mutated so that it would contain an NcoI site at the same 5′ end site as the wt gfp gene. The sequence upstream of this NcoI site was also replaced by the 5′ end of wt gfp. This resulted in the construction of the second chimeric gfp gene, which we have designated gfp-NcoI (Fig. 3D). Chimeric gfp-BstBI and gfp-NcoI were inserted into retroviral vectors, and the vector DNAs were each introduced into helper cell lines. Cells that contained the two chimeric gfp genes emitted bright green light under a fluorescence microscope (data not shown). These results indicated that the two chimeric gfp genes were functional.

(v) Introduction of a frameshift mutation into the gfp gene.

To introduce a frameshift mutation into the gfp gene, the gfp-BstBI gene sequence was digested with BstBI, followed by repair with Klenow fragment. BstBI digestion creates two DNA ends that contain a 2-base overhang. When the overhang was repaired by the Klenow fragment, it created two blunt ends. Ligation of these two blunt ends with T4 ligase created a 2-bp insertion, which shifted the gfp open reading frame by two (+2). The gfp-NcoI was digested with NcoI, followed by repair with the Klenow fragment and ligation. NcoI digestion created two DNA ends that contained a 4-base overhang. As a result, this shifted the gfp open reading frame by one (+1). The first gfp gene contained a frameshift mutation at BstBI within the 3′ end of the gfp gene, and the second gfp gene contained another frameshift mutation at the NcoI site within the 5′ end of the gfp gene. The two mutated gfp genes contained identical sequences between their individual frameshift mutation sites, which were separated by about 0.55 kb. The gfp gene is approximately 0.7 kb in length.

(vi) Construction of pJZ425 and pJZ468.

JZ425 (Fig. 3E) contained the frameshift mutation gfp-BstBI gene, the hygromycin resistance gene (hyg), and an internal ribosome entry segment (IRES) sequence located between the two genes. The gfp gene was expressed by the conventional ribosome scanning model from the viral 5′ R region, while the hyg gene in JZ425 was expressed by the IRES (1, 4). In pJZ425, the 4.6-kb ClaI-BamHI fragment (from positions 4055 to 1630) was isolated from pLNCX (19) and contained the two MLV LTRs. The 0.7-kb BamHI-SalI fragment (from positions 1631 to 2389) was derived from gfp-BstBI (Fig. 3C) and contained a frameshift mutation at the BstBI site. The 0.6-kb SalI-NdeI fragment (from positions 2390 to 2991), which contained the IRES sequence, was isolated from pCITE-1 (Novagen, Madison, Wis.). The 1.1-kb NdeI-ClaI fragment (from positions 2992 to 4054) was isolated from pJD214 Hyg (9) and contained the hyg sequence.

The retroviral vector JZ468 (Fig. 3F) was similar to JZ425, except that JZ468 contained the gfp gene with the frameshift mutation at the NcoI site (Fig. 3D) and the neo gene. In pJZ468, the 5.4-kb NdeI-BamHI fragment (from positions 2993 to 1630) was isolated from pLN and contained the neo gene and the two MLV LTRs. The 0.7-kb BamHI-SalI fragment (from positions 1631 to 2391) was derived from gfp-NcoI (Fig. 3D) and contained a frameshift mutation at the NcoI site. The 0.6-kb SalI-NdeI fragment (from positions 2392 to 2992) was isolated from pCITE-1 (Novagen) and contained the IRES sequence.

Preparation of virus LT5.

DNA of pLT5 was used to transfect the xenotropic helper cell line PG13 (18) using Lipofectamine Plus (Life Technologies, Grand Island, N.Y.) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Three hours after transfection, cells were washed four times with Dulbecco modified Eagle medium to remove the residual DNA from the plates. Viruses were detected as early as 6 h by infection of D17 cells and selection for neomycin resistance (Neor). The viruses were collected 10 to 12 h after transfection.

Isolation of Neor cellular DNA and amplification of the PBS.

D17 cells infected with LT5 were selected for Neor with visible colonies formed about 12 days after infection. Well-separated colonies were cloned into 24-well plates. The cells were harvested once they covered the bottom of the well. Cellular chromosomal DNAs were isolated with a Wizard genomic DNA purification kit (Promega) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

The PBS region was amplified using primer U3 601 (GGCAAGCTAGCTTAAGTAACGC), located at the U3 region, and primer Neo-rev (CCACCCAAGCGGCCGGAGAA), located at the neo gene, for 25 cycles. Primers were removed with a Wizard PCR Preps DNA purification kit (Promega) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The PCR product was further amplified using primer U3-2770 (CCAGATGCGGTCCAGCCC), located between the U3 region (downstream of U3 601) and primer MLV BstEII (AGCAGAAGGTAACCCAACGTCT), located at the package signal.

Cells, transfection, and infection.

The processing of D17 cells (ATCC CRL-8468), PA317 helper cells (ATCC CRL-9078), and PG13 helper cells (ATCC CRL-10686); DNA transfections; virus harvesting; and virus infections were performed as previously described (28).

Fluorescence microscopy.

An inverted fluorescence microscope (Zeiss Axiovert 25) with a mercury arc lamp (100 W) and a fluorescence filter set (CZ909) consisting of a 470- by 40-nm exciter, a 515-nm emitter, and a 500-nm beam splitter was used to detect green fluorescent protein in living cells.

Relations between hyg and neo RNA frequencies in the step 3 virion.

The relations between hyg and neo RNA frequencies in the step 3 virion were described previously (28). The relation between hyg and neo RNA frequencies in step 3 virions can be described in algebraic terms by means of the Hardy-Weinberg equation as follows.

Let h be the frequency of hyg RNA in STEP 3 virions and n be the frequency of neo RNA in step 3 virions, so that h + n = 1.

Assuming random packaging, the frequencies of different hyg and neo dimers are determined with the formula h2 + 2hn + n2 = 1, where h2 is the frequency of virions containing two hyg RNAs, 2hn is the frequency of virions containing one hyg RNA and one neo RNA, and n2 is the frequency of virions containing two neo RNAs. Neor colonies result from infection by all virions containing two neo RNAs and half virions containing one neo and one hyg RNA. Therefore, the frequency of virions capable of forming Neor colonies is determined as follows: Tn = n2 + hn, where Tn is the titer of Neor CFU. The frequency of virions capable of forming hygromycin-resistant (Hygr) colonies is determined with the formula Th = h2 + hn. These last two equations can be resolved with the equation h = Th/(Tn + Th) and also n = Tn/(Tn + Th).

Therefore, the number of virions containing one hyg RNA and one neo RNA (2hn) is (2Th × Tn)/(Tn + Th)2.

RESULTS

Construction of a retroviral vector that contained a mutation within the PBS.

Retroviral replication uses host tRNA as its primer. A host tRNAPro binds to an 18-base sequence of the MLV genome. This 18-base sequence is called the PBS (8). The 18-base sequence, TGGGGGCTCGTCCGGGAT, is complementary to the tRNAPro 3′ end on the acceptor arm. The T at the 11th nucleotide (underlined) was changed to C using a PCR technique so that the 11th to 16th nucleotides within the PBS could be digested with SmaI (CCCGGG). This MLV vector was derived from pLN (19). The pLN plasmid contains a neomycin resistance gene between two MLV LTRs. The 3′ LTR of pLN was cloned from a 5′ LTR that contained a PBS positioned downstream of the 3′ LTR. Fifteen percent of the progeny virus utilized the downstream 3′ LTR PBS to initiate minus-strand DNA synthesis, and a complete minus-strand DNA can be transcribed without a strong stop DNA jump (J. Zhang, unpublished data). To force all progeny viruses to use their natural PBS, the PBS downstream from the 3′ LTR was deleted using standard PCR techniques. The vector designated LT5 (Fig. 2A), which contained a deletion of this 3′ PBS, was constructed so that it contained a SmaI site within its normally positioned PBS.

Majority of mismatches within MLV double-stranded DNA was not corrected by D17 cells.

DNA containing the vector LT5 was transfected into a murine retroviral helper cell line PG13 (18). The virus-containing cell supernatants were collected 10 h after transfection. The viruses were used to infect D17 cells. Since the target cells did not contain the retrovirus structural genes (gag-pol and env), virus was not released from infected target cells after infection with the retrovirus vector (28). Therefore, this infection assay represented only a single round of replication. Since pLT5 (DNA) contained a mutation in its PBS region (Fig. 2A), the virus RNA transcribed from the viral DNA also contained this mutation. After this viral vector entered D17 cells, the single-stranded RNA was reverse transcribed into double-stranded DNA. The PBS within the minus-strand DNA was copied with the viral RNA molecule as its template, while the plus-strand PBS DNA was synthesized with the host tRNAPro as its template (8). As a consequence, the viral double-stranded DNA contained a mismatch within this PBS. The viral double-stranded DNA was then integrated into the host chromosome as a provirus. Infected D17 cells were selected for Neor, and resistant colonies appeared in about 12 days. Well-separated individual colonies were cloned, and the DNAs from cells of these single colonies were isolated. The cellular DNA of each colony was amplified using two primers. The upstream primer (U32770) was located within the U3 region of the LTR, while the downstream primer was located within the packaging signal (MLV BstEII). The amplified fragment was 893 bp in length.

If the target cells (D17 cells) were capable of mismatch repair before the infected cells divided, all cells in the Neor colony would contain either all mutant PBSs or the wt PBS. If the target cells did not repair the mismatch, half of the cells in the colony would contain the mutant PBS and the other half of the cell population would contain the wt PBS. The amplified fragments were digested with SmaI. Amplified fragments with the wild-type PBS contained a SmaI site in the R region. After digestion, the amplified wild-type product was cut into two fragments of 686 and 207 bp in length (Fig. 2B, lane 2). The amplified mutant PBS fragments contained an additional SmaI site within the PBS. After being digested with SmaI, three fragments of 558, 207, and 128 bp in length (Fig. 2B, lane 1) were observed for the mutant product. Twenty-two of 24 Neor colonies examined (Fig. 2B, lanes 3 to 26) contained both wt and mutant PBS sequences in the DNA isolated from a single colony. Only one of the 24 clones contained only the wt PBS (Fig. 2B, lane 14) and one of the 24 clones contained only the mutant PBS (Fig. 2B, lane 5). Therefore, the target cells (D17) were unable to repair the majority of mismatches within MLV double-stranded DNA. The frequency of the mismatch repair in the D17 cells was less than 10% before division.

Construction of vectors for the determination of the mechanisms of retroviral recombination.

Two additional MLV vectors were constructed. The first vector contained a drug resistance gene (hyg) and an unselected color reporter gene (gfp-BstBI−) between the two MLV LTRs and is designated JZ425 (Fig. 3E). The gfp-BstBI− gene was expressed downstream of the viral 5′ R region, while the hyg gene in JZ425 was expressed downstream of an IRES (1, 4). This IRES allows internal ribosome binding to the transcript expressed from the 5′ LTR retroviral promoter. gfp-BstBI− contained a frameshift mutation near its 3′ end, inside the gene's open reading frame. As a result of this frameshift, the gfp gene was no longer functional. The second vector, JZ468 (Fig. 3F), contained another selectable marker, neo, and an unselected color reporter gene, gfp-NcoI−, between the two MLV LTRs. gfp-NcoI− contained a frameshift mutation at the NcoI site. Cells containing either JZ425 or JZ468 did not emit green light (data not shown). These two frameshift mutations are separated by 0.55 kb, while the gfp gene is about 0.7 kb in length.

The rates of backward frameshift mutation of JZ425 and JZ468 were very low.

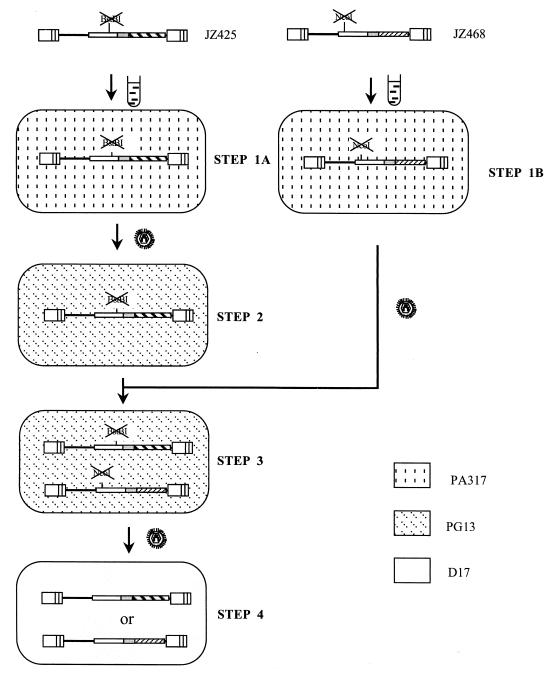

pJZ425 was used for transfection into the MLV amphotropic helper cell line PA317 (17). PA317 cells containing pJZ425 were designated step 1A cells (Fig. 4). Viruses from step 1A cells were used to infect the xenotropic helper cell line PG13 (18). Infected cells were selected for Hygr. Four individual Hygr cell clones were isolated and designated step 2 cells. The pJZ468 vector was used for transfection into fresh PA317 cells. PA317 cells containing JZ468 were designated step 1B cells (Fig. 4). Viruses from step 1B cells were used to infect fresh PG13 cells. Infected cells were selected for Neor. Four individual Neor cell clones were isolated.

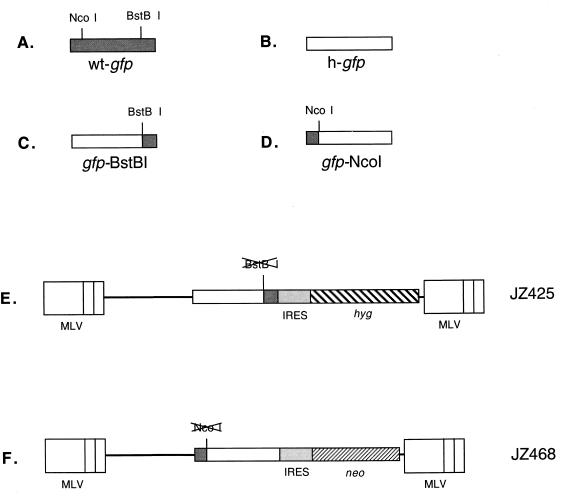

FIG. 4.

Outline of an experimental approach for the determination of the rate of recombination during a single cycle of retroviral replication. No plasmid backbone sequences are shown. Transfections are indicated by test tube shapes. Infections are indicated by virion shapes. The different backgrounds represent the indicated cell lines. The lines in the LTR separate the U3, R, and U5 regions. The provirus in step 4 cells is the construct of Neor or Hygr recombinants, which result from recombination between the two frameshift mutations located on pJZ425 and pJZ468 (step 3).

To confirm that the backward frameshift mutation (or the secondary frameshift mutation) rate is low, the viruses harvested from the step 2 Hygr cells were used to infect D17 target cells. The infected cells were selected for Hygr. The Hygr colonies were examined under a fluorescence microscope. Likewise, the supernatant containing viruses harvested from PG13 cells which contained JZ468 were used to infect D17 cells. The infected cells were selected for Neor. The Neor colonies were examined under a fluorescence microscope. A total of 105 Hygr colonies of D17 cells infected with JZ425 and 105 Neor colonies of D17 cells infected with JZ468 were examined, and no green colonies were detected. This result indicates that the backward frameshift mutation of JZ425 and JZ468 was undetectable.

Determination of the rate of retroviral recombination.

Figure 4 shows the outline of an experimental approach for the determination of the rate of retroviral recombination. The virus from step 1B cells was used to infect step 2 Hygr cells. The two vector proviruses were introduced into a single helper cell line by selection for Neor. Individual well-separated Neor PG13 cells were cloned. PG13 cells containing JZ425 and JZ428 were designated step 3 cells (Fig. 4). Viruses from this step 3 helper cell line can contain two nonidentical RNA molecules, one transcribed from provirus JZ425 and the other transcribed from provirus JZ468. Viruses from this helper cell line were used to infect target D17 cells. Infected cells were selected for Hygr and Neor, respectively. Unlike the helper cell lines, these target cells do not contain the retroviral structural genes (gag-pol and env), so that after infection with the retrovirus vector, no virus was released from the infected target cells (28). Thus, this infection represented only a single round of replication. Since both proviruses in PG13 cells contain a frameshift mutation within their gfp genes, if not mutation or recombination events occur, no green Neor (or Hygr) colonies should be observed. Green Neor (and Hygr) colonies can occur by two plausible mechanisms. The first possibility is that a reverse mutation occurs to overcome the frameshift mutation, but this is less likely since the reverse frameshift mutation rate is very low (<10−5) (see above). The second possibility that may cause a green colony to form is that a recombination event occurs between the two frameshift mutation sites of these two vectors. The two frameshift mutations are located at a distance of 0.55 kb from one another. The ratio of the number of green colonies to the number of virions which contain both hyg (JZ425) RNA and neo (JZ468) RNAs is the rate of recombination during a single round of retroviral replication. To limit double infections, the multiplicity of infection was lower than 1:1,000. To determine if green colonies resulted from a single infection, 11 green colonies were randomly isolated. The DNA of each colony was digested with BamHI and hybridized with a gfp probe. BamHI digested JZ425 and JZ468 proviral DNAs 5′ of the gfp gene and in cellular flanking sequences 3′ of the gfp gene. All of 11 colonies analyzed contained only one copy of the gfp gene, indicating that most green cells did not result from double infections (data not shown).

The ratio of the number of green colonies to the number of virions that contained both hyg (JZ425) RNA and neo (JZ468) RNA was about 0.17% ± 0.14% or 0.80% ± 0.43% per replication cycle, which represent the rate of recombination (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Microscopic analysis of D17 cells infected with JZ468 and JZ425

| Clone | No. of cells with indicated trait infected with JZ425/JZ468

|

Rate of recombination (%)g | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neor/Hygra | Virions containing neo and hyg RNAb | Solid greenc | Mixed coloniesd | Not well separatede | Total coloniesf | ||

| 1-1 | 8,100/5,490 | 4,050/8,235 | 7/13 | 2/1 | 43/0 | 52/14 | 1.3/0.17 |

| 1-2 | 4,140/2,496 | 1,356/4,181 | 15/8 | 3/1 | 0/0 | 18/9 | 1.3/0.22 |

| 2-1 | 2,646/2,400 | 1,462/3,480 | 8/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 8/0 | 0.54/0 |

| 2-2 | 4,324/4,100 | 2,275/6,050 | 12/5 | 3/2 | 1/0 | 16/7 | 0.70/0.12 |

| 3-1 | 7,155/7,560 | 3,395/11,529 | 8/14 | 1/1 | 3/0 | 12/15 | 0.35/0.13 |

| 3-2 | 4,350/3,649 | 3,619/4,264 | 11/4 | 6/0 | 6/1 | 23/5 | 0.64/0.12 |

| 4-1 | 5,980/8,820 | 1,047/15,960 | 6/8 | 6/5 | 2/8 | 14/21 | 1.3/0.13 |

| 4-2 | 6,027/4,324 | 7,732/3,090 | 13/15 | 4/0 | 7/0 | 24/15 | 0.30/0.49 |

| Total | 42,722/38,839 | 80/67 | 25/10 | 62/9 | 167/86 | 0.8 ± 0.43/0.17 ± 0.14h | |

Total numbers of colonies observed.

Numbers of virions which contained both hyg and neo RNAs (or JZ425 and JZ468) as described in Materials and Methods.

Numbers of colonies observed that contained only green cells.

Numbers of colonies observed that contained both green cells and clear cells.

Numbers of colonies observed that contained green cells and were in such close proximity with the other colonies that it was difficult to determine the nature of the colonies.

Numbers of total colonies that contained green cells, i.e., the sum of the numbers of colonies defined in footnotes c, d, and e.

The ratio of the total number of colonies as defined in footnote f to the number of virions which contained both hyg and neo RNAs, as defined in footnote b.

Values are means ± standard deviations.

Most retroviral recombinations occur during minus-strand DNA synthesis.

If recombination occurred during minus-strand DNA synthesis, the minus-strand DNA would contain a functional gfp sequence, and since the plus-strand DNA uses the minus-strand DNA as a template, the plus-strand DNA would contain the functional gfp sequence. After the cell divides, all the cells in a Neor (or Hygr) colony would be green. However, if the recombination occurs during plus-strand DNA synthesis, then only the plus-strand DNA would contain a functional gfp sequence and the minus-strand DNA would still carry a frameshift mutation. The double-stranded DNA containing this mismatch subsequently integrates into the host chromosomal DNA of the D17 cells, which are unable to repair the majority of mismatches within retroviral DNA. After the cell divides, one daughter cell would carry a functional gfp sequence while the other daughter cell would contain a frameshift mutation in the gfp sequence. Under fluorescence microscopy, one-half of the cells in this colony should be green and one-half of the cells in this colony should be clear.

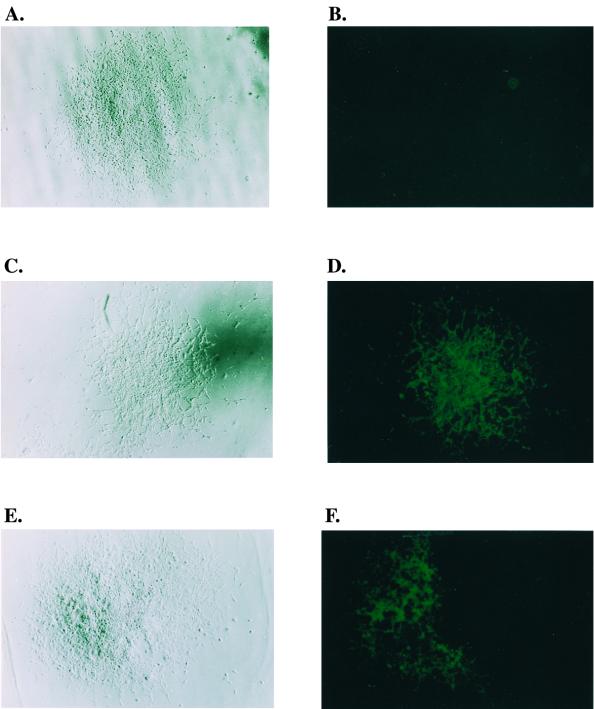

To determine the mechanism of recombination, each Hygr and Neor colony was carefully examined under a fluorescence microscope for green cells. More than 80,000 colonies (42,000 Neor colonies and 38,000 colonies Hygr) were examined. Among them there were 105 (77%) well-separated solid green colonies (Fig. 5C and D) and 32 (23%) well-separated mixed colonies (Fig. 5E and F). (In addition, 71 colonies contained green cells that were in such close proximity with other colonies that it was difficult to determine the exact nature of the colonies.) A colony of solid green indicates that the recombination had occurred during minus-strand DNA synthesis, while a colony of cells containing both clear and green cells indicates that either the mixture was a result of a recombination that was formed during plus-strand DNA synthesis or that the mixture was the result of the close contact between two cells infected with different viruses. One (green cell) of the two infected cells resulted from a recombination between JZ425 and JZ468 during minus-strand DNA synthesis, and the other resulted from a parental viral infection (clear cells). The former resulted from one integration event, while the latter resulted from two integration events.

FIG. 5.

Microscopic analyses of D17 cells infected with viruses from step 3 cells. (A) Visible light microscopy of a Hygr colony, which contains the parental type of Hygr provirus. (B) Fluorescence microscopy of a Hygr colony, which contains the parental type of Hygr provirus. The same colony as that shown in panel A was examined under a fluorescence microscope. (C) Visible light microscopy of a Hygr colony which resulted from a recombination between JZ425 and JZ468. (D) Fluorescence microscopy of a solid green Hygr colony, which resulted from a recombination between JZ425 and JZ468. The same colony as that shown in panel C was examined under fluorescence microscopy. (E) Visible light microscopy of a Hygr mixed cell colony, which contains both green and clear cells. (F) Fluorescence microscopy of a Hygr mixed cell colony, which contains both green and clear cells. The same colony as that shown in panel C was examined under fluorescence microscopy.

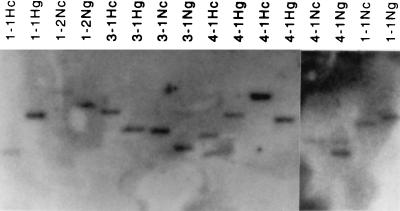

The colonies containing both clear and green cells were subcloned. The cellular DNAs from clear cells and green cells were isolated from these subclones. Cellular DNA was digested with BamHI and hybridized with a gfp probe. BamHI digested JZ425 and JZ468 proviral DNA 5′ of the gfp gene and in cellular flanking sequences 3′ of the gfp gene. If a recombinant colony containing both clear and green cells resulted from a recombination, the provirus in the clear and green cells should integrate at the same site; therefore, the BamHI-digested gfp fragments from the clear and green cells should be the same length. Southern blot analysis indicated that the proviruses in the clear and green cells were integrated at different sites in 11 of 12 mixed colonies analyzed (Fig. 6). The green cells of one mixed colony (Fig. 6, lane 4-1Ng) contained an additional copy of the gfp fragment, suggesting that either a parental infection of one daughter cell followed a plus-strand recombination or a recombinant infection of one daughter cell followed a parental infection. Therefore, about 92% [1 − (1/12)], if not all, of the mixed colonies resulted from two independent integration events. If the D17 cells could not repair 100% of the mismatches, we estimate that approximately 98%, if not all, of the retroviral recombinations resulted from a mechanism that is engaged during minus-strand DNA synthesis {[1 − 23% × (1 − 92%)] = 98%}. Since the D17 cells were still able to repair only about 10% of the mismatches, it appears that the frequency of recombination during plus-strand synthesis is extremely low.

FIG. 6.

Southern blot analysis of recombinants between JZ425 and JZ468. Chromosomal DNAs of Hygr (H) or Neor (N) step 4 clones were used. Cellular DNAs isolated from green (g) cells and clear (c) cells were digested with BamHI and hybridized to a gfp gene probe.

DISCUSSION

Eukaryotic cells possess several distinct mismatch repair pathways. A mismatch can be introduced in retroviral double-stranded DNA by a preexisting mutation within the PBS of the viral RNA genome. MLV-based vectors with a mutation in their PBSs were used to infect mismatch-repair-competent cell lines as well as mismatch-repair-deficient cell lines. Almost all mismatch-repair-deficient cells colonies analyzed (cell lines HCT 116 and PMS2−/−) (2, 10, 20, 21) contained both the wild-type and mutated PBS. Therefore, mismatches within retroviral double-strand DNA could not be repaired by the mismatch-repair-deficient cells. Only 2 of 45 colonies analyzed showed a pattern corresponding to the presence of a repaired PBS. The two exceptions probably represent an infected cell that divided into two daughter cells and one daughter cell died so that the resulting colony contained only either the wild-type or the mutant PBS (11). Two of 24 (10%) D17 colonies analyzed showed a pattern corresponding to the presence of a repaired PBS, suggesting that D17 is a mismatch-repair-deficient cell line.

In contrast, approximately 25% of the mismatch-repair-competent cell clones analyzed (cell lines HeLa and PMS2+/+) were repaired while 75% were not. Therefore, the normal cellular mismatch repair system is not able to repair the majority of mismatches within the viral double-stranded DNA. One possible explanation is that the cells do not have enough time to repair the mismatch after integration of the double-strand DNA before the cell divides. After a retrovirus enters host cells, the single-strand RNA genome is reverse transcribed into double-strand DNA within the retroviral capsid in the host cell cytoplasm. Before retroviral integration, the retroviral double-stranded DNA exists as a structure called the preintegration complex (PIC) (8). This PIC contains retroviral capsid protein and other proteins. The cellular mismatch repair system is probably unable to recognize a DNA mismatch within this PIC. MLV, like other simple retroviruses, can infect only dividing cells, and it has been hypothesized that the PIC enters the nucleus only during mitosis (8, 11). Therefore, the window for the cellular mismatch repair system to repair a mismatch within the retroviral double-stranded DNA would be constrained to mitosis. Only a very low percentage of mismatches within retroviral double-stranded DNA were repaired in these experiments.

Previous reports suggested that a recombinant may be a result of one or more crossover events (13). In our system, one crossover is sufficient to form a Neor recombinant. The reverse transcription growing points synthesize the neo gene and the 3′ end of the gfp gene using JZ468 as a template and then shift to the JZ425 RNA to complete the functional gfp gene (Fig. 3E and F). However, the formation of a Hygr recombinant requires at least two crossover events. The reverse transcription growing points at first synthesize the hyg gene using JZ425 as the template and then shift the template to copy the 3′ end of the gfp gene from JZ468. The template is shifted once again to copy the 5′ end of the gfp gene of JZ425. Results in this report indicate that the Hygr recombinants formed with approximately equal frequencies as Neor recombinants, which indicates that the two crossover events occurred at the same rate as one crossover event during the minus-strand DNA synthesis. Furthermore, these results suggest that after one recombination occurs, the frequency of a second recombination rate must be much higher than the average recombination rate.

In this report, we have estimated that most, if not all, recombinations occur during minus-strand DNA synthesis. Therefore, the mechanism of retroviral recombination is either the copy choice model or the minus-strand replacement model. Further work needs to be done to distinguish between these two minus-strand DNA synthesis models.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank W. Bargmann, K. Boris-Lawrie, G. Li, and A. Kaplan for helpful comments on the manuscript.

This research was supported by Public Health Service research grant CA70407 from the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adam M A, Ramesh N, Miller A D, Osborne W R. Internal initiation of translation in retroviral vectors carrying picornavirus 5′ nontranslated regions. J Virol. 1991;65:4985–4990. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.9.4985-4990.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baker S M, Bronner C E, Zhang L, Plug A W, Robatzek M, Warren G, Elliott E A, Yu J, Ashley T, Arnheim N, et al. Male mice defective in the DNA mismatch repair gene PMS2 exhibit abnormal chromosome synapsis in meiosis. Cell. 1995;82:309–319. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90318-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berwin B, Barklis E. Retrovirus-mediated insertion of expressed and non-expressed genes at identical chromosomal locations. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:2399–2407. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.10.2399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boris-Lawrie K A, Temin H M. Recent advances in retrovirus vector technology. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1993;3:102–109. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(05)80349-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chalfie M, Tu Y, Euskirchen G, Ward W W, Prasher D C. Green fluorescent protein as a marker for gene expression. Science. 1994;263:802–805. doi: 10.1126/science.8303295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coffin J M. Retroviridae: the viruses and their replication. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, editors. Fields virology. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1996. pp. 1767–1847. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coffin J M. Structure, replication, and recombination of retrovirus genomes: some unifying hypotheses. J Gen Virol. 1979;42:1–26. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-42-1-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coffin J M, Hughes S H, Varmus H. Retroviruses. Plainview, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dougherty J P, Temin H M. High mutation rate of a spleen necrosis virus-based retrovirus vector. Mol Cell Biol. 1986;6:4387–4395. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.12.4387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drummond J T, Li G M, Longley M J, Modrich P. Isolation of an hMSH2-p160 heterodimer that restores DNA mismatch repair to tumor cells. Science. 1995;268:1909–1912. doi: 10.1126/science.7604264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hajihosseini M, Iavachev L, Price J. Evidence that retroviruses integrate into post-replication host DNA. EMBO J. 1993;12:4969–4974. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06190.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hu W S, Temin H M. Genetic consequences of packaging two RNA genomes in one retroviral particle: pseudodiploidy and high rate of genetic recombination. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:1556–1560. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.4.1556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu W S, Temin H M. Retroviral recombination and reverse transcription. Science. 1990;250:1227–1233. doi: 10.1126/science.1700865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang C C, Hammond C, Bishop J M. Nucleotide sequence and topography of chicken c-fps. Genesis of a retroviral oncogene encoding a tyrosine-specific protein kinase. J Mol Biol. 1985;181:175–186. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(85)90083-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Junghans R P, Boone L R, Skalka A M. Products of reverse transcription in avian retrovirus analyzed by electron microscopy. J Virol. 1982;43:544–554. doi: 10.1128/jvi.43.2.544-554.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Junghans R P, Boone L R, Skalka A M. Retroviral DNA H structures: displacement-assimilation model of recombination. Cell. 1982;30:53–62. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90011-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller A D, Buttimore C. Redesign of retrovirus packaging cell lines to avoid recombination leading to helper virus production. Mol Cell Biol. 1986;6:2895–2902. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.8.2895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller A D, Garcia J V, von Suhr N, Lynch C M, Wilson C, Eiden M V. Construction and properties of retrovirus packaging cells based on gibbon ape leukemia virus. J Virol. 1991;65:2220–2224. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.5.2220-2224.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller A D, Rosman G J. Improved retroviral vectors for gene transfer and expression. BioTechniques. 1989;7:980–990. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parsons R, Li G M, Longley M J, Fang W H, Papadopoulos N, Jen J, de la Chapelle A, Kinzler K W, Vogelstein B, Modrich P. Hypermutability and mismatch repair deficiency in RER+ tumor cells. Cell. 1993;75:1227–1236. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90331-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prolla T A, Baker S M, Harris A C, Tsao J L, Yao X, Bronner C E, Zheng B, Gordon M, Reneker J, Arnheim N, Shibata D, Bradley A, Liskay R M. Tumour susceptibility and spontaneous mutation in mice deficient in Mlh1, Pms1 and Pms2 DNA mismatch repair. Nat Genet. 1998;18:276–279. doi: 10.1038/ng0398-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raines M A, Maihle N J, Moscovici C, Crittenden L, Kung H-J. Mechanism of c-erbB transduction: newly released transducing viruses retain poly(A) tracts of erbB transcripts and encode C-terminally intact erbB proteins. J Virol. 1988;62:2437–2443. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.7.2437-2443.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sapp C M, Li T, Zhang J. Systematic comparison of a color reporter gene and drug resistance genes for the determination of retroviral titers. J Biomed Sci. 1999;6:342–348. doi: 10.1007/BF02253523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Swain A, Coffin J M. Mechanism of transduction by retroviruses. Science. 1992;255:841–845. doi: 10.1126/science.1371365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vieira J, Messing J. The pUC plasmids, an M13mp7-derived system for insertion mutagenesis and sequencing with synthetic universal primers. Gene. 1982;19:259–268. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(82)90015-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang J, Sapp C M. Recombination between two identical sequences within the same retroviral RNA molecule. J Virol. 1999;73:5912–5917. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.7.5912-5917.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang J, Temin H M. Rate and mechanism of nonhomologous recombination during a single cycle of retroviral replication. Science. 1993;259:234–238. doi: 10.1126/science.8421784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]