Introduction

Over recent decades the incidence of Crohn's disease has increased in the United Kingdom and it now affects about 1 in 1500 people. Symptoms start at any age, with peaks in early and late adulthood. Although the disease is incurable its adverse effects on health and quality of life can be substantially reduced by appropriate treatment. This paper reviews the current management of adults with common presentations of Crohn's disease.

Summary points

Morbidity from Crohn's disease can be lessened by meticulous specialist management

New techniques for clarifying the site of disease, activity, and complications include scanning with radiolabelled leucocytes, ultrasound, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging

Budesonide, high dose mesalazine and, for refractory disease, methotrexate and antitumour necrosis factor α antibody are new therapeutic options

Other new therapeutic possibilities include a liquid formula diet, endoscopic stricture dilatation, and laparoscopic surgery

The most effective measure for maintenance of remission is stopping smoking

Patients should participate in decisions about their treatment

Methods

I searched Medline with the key terms Crohn's disease, drug therapy, dietary therapy, surgery, and therapy. Pharmacotherapeutic advances were derived from peer reviewed controlled clinical trials and meta-analyses published since 1993. Recent data were from the annual meeting of the American Gastroenterological Association. Citations about other aspects of Crohn's disease were mainly from review articles.

Aetiopathogenesis

The progressive elucidation of the pathogenesis, if not yet the cause, of Crohn's disease has improved our understanding of the possible modes of action of conventional treatment and has led to the development of new anti-inflammatory agents aimed at specific pathophysiological targets.

Epidemiological and genetic studies suggest that Crohn's disease is a polygenic disorder without any single Mendelian pattern of inheritance. Susceptibility loci for the disease have been reported recently on chromosomes 16, 3, 7, and 12; the latter three being shared with ulcerative colitis.1 Several environmental factors have been implicated.1 Claims for initiating roles for gut flora, food constituents, or specific infections such as mycobacterium paratuberculosis and measles have not yet been substantiated. The pathogenic significance of the strong association between cigarette smoking and Crohn's disease, and why smoking worsens the clinical course of the disease,2 remains unclear.

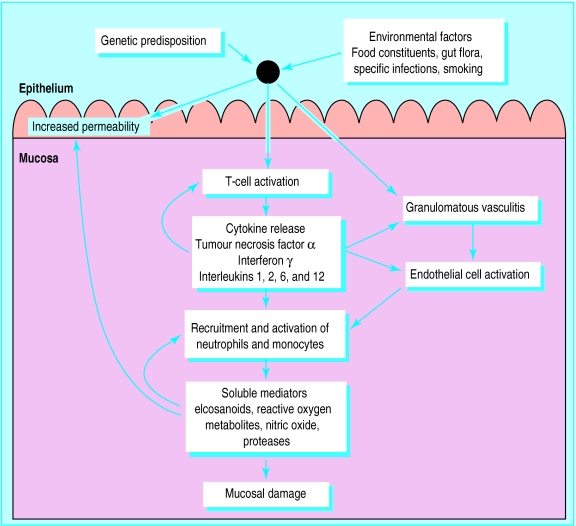

Whatever the initiating factors in Crohn's disease, excessive activation of mucosal T cells leads to transmural inflammation, which is amplified and perpetuated by the release of proinflammatory cytokines and soluble mediators (fig 1).1

Figure 1.

Aetiopathogenesis of Crohn's disease. Genetic and environmental factors activate mucosal T lymphocytes causing cytokine driven inflammation; increased epithelial permeability and granulomatous vasculitis, leading to focal intestinal microinfarction, may also contribute to the inflammatory process1

Assessment

Treatment of Crohn's disease depends not only on the site of the disease but also on the pathological process underlying the patient's presentation.3,4 Inflammation, obstruction, abscess, and fistula need to be distinguished by appropriate investigation (table).Clinical evaluation and blood tests5 remain central to the assessment of symptomatic Crohn's disease, but recently there have been changes in the subsequent diagnostic approach.

Conventional radiology and colonoscopy

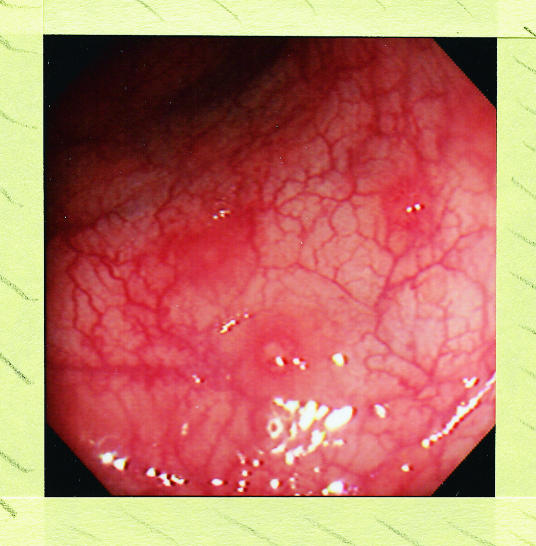

Plain abdominal radiography is still essential if intestinal obstruction is suspected: as in ulcerative colitis it helps to estimate the extent and severity of Crohn's colitis. For imaging the small intestine a barium follow through is more comfortable for patients, is less likely to miss proximal disease, and is safer than a small bowel enema (enteroclysis).6 Colonoscopy with ileoscopy, because it allows detection of superficial disease, biopsy and, when necessary, dilatation of strictures is now usually preferred to barium enema for investigation of the lower bowel (fig 2).6 Colonoscopy may also have a role, as in ulcerative colitis, in surveillance for colorectal cancer in patients with longstanding extensive Crohn's colitis.7

Figure 2.

Superficial aphthoid erosions in sigmoid colon in patient with ileocolonic Crohn's disease. Subtle lesions such as these are more readily seen at ileocolonoscopy than on barium enema

Newer imaging techniques

Scanning with radiolabelled leucocytes identifies sites of intestinal inflammation and intra-abdominal abscess non-invasively. Labelling with 99technetium-hexamethyl propylene amine oxime is superior to 111indium tropolonate in ease of use, availability, image quality, and radiation dose.6 Scintigraphic scanning with monoclonal antibodies to upregulated cellular adhesion molecules such as E selectin represents an ingenious application of improved understanding of the pathogenesis of Crohn's disease.1,8

Transabdominal ultrasound for the assessment of bowel wall abnormalities, abscess, and fistula is becoming more widespread.6 Changes in mucosal and superior mesenteric arterial blood flow indicating active Crohn's disease are detectable by colour Doppler ultrasound, whereas endoanal and transvaginal ultrasound can help to evaluate perianal disease. Although its non-invasive nature and lack of radiation exposure make ultrasound an appealing investigative technique results are dependent on operator skill and equipment quality.

Abdominal computed tomography now has a major role in the diagnosis of abscess, fistula, and perianal and parastomal complications of Crohn's disease.6 The contribution of magnetic resonance imaging is evolving but it is already invaluable for the delineation of pelvic and perianal disease.9

Treatment of active ileocaecal Crohn's disease

General measures

Explanation, hospital care, and dietary advice

Patients need their illness fully explained, not least to enable them to participate in decisions about their therapy: discussion can be reinforced with information from support groups such as the National Association for Colitis and Crohn's disease. Hospital care is best undertaken by a team of medical and surgical gastroenterologists, dieticians, and nurse practitioners with a special interest in inflammatory bowel disease, nutrition, and stoma care. Undernourished patients need liquid protein supplements, whereas special nutritional measures are required for patients with short bowel syndrome due to extensive Crohn's disease or resection.10

Non-specific drugs

Codeine phosphate and loperamide remain useful antidiarrhoeal agents in Crohn's disease but may cause acute colonic dilatation in active colitis. By binding bile salts cholestyramine (4 g 1-3 times daily) reduces diarrhoea due to terminal ileal disease or resection. Haematinics, calcium, magnesium, zinc, and fat soluble vitamins may be needed for the replacement of particular deficiencies as may bisphosphonates, calcium, vitamin D, and hormone replacement therapy for osteoporosis. Sick inpatients may require intravenous fluid and electrolytes and blood transfusion, with subcutaneous heparin to reduce the risk of systemic venous thromboembolism.11Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may precipitate relapse of inflammatory bowel disease12 and should be avoided.

Specific drug therapy

Clinical trials in Crohn's disease are bedevilled by difficulties in defining outcome measures, and by the heterogeneity, fluctuating course, and unpredictable placebo response of the disease.13 Nevertheless, several new treatments have been introduced recently as a result of well conducted controlled trials.

Corticosteroids

In active disease oral steroids still provide the quickest and most reliable response; about 70% of patients improve within 4 weeks. Conventionally, prednisolone (40-60 mg/day) is used, the dose being tapered by 5 mg every 7-10 days once improvement has begun. Very ill patients, or those with intestinal obstruction, need intravenous hydrocortisone or methylprednisolone initially.

Budesonide is a new steroid with high topical potency; because of poor absorption and rapid first pass metabolism it causes less adrenocortical suppression than prednisolone. Formulated in a pH sensitive coating, which delivers the drug to the distal ileum and caecum, budesonide (Entocort CR (Astra) or Budenofalk (Cortecs), 9 mg/day) approaches oral prednisolone (40 mg/day) in efficacy in ileocaecal Crohn's disease.14–16 It has become a useful although comparatively expensive option for patients in whom minimisation of steroid induced side effects is particularly important.

Aminosalicylates

The newer oral 5-aminosalicylate formulations are better tolerated than sulphasalazine and can be used in higher doses. The pH dependent delayed release (Asacol, Salofalk) and, particularly, slow release (Pentasa) mesalazine preparations release 5-aminosalicylate more proximally in the gut than sulphasalazine making them useful in small bowel disease as well as colitis. High dose oral mesalazine (Pentasa 2 g twice daily, Asacol 1.2 g three times daily) given for up to 4 months induces remission in about 40% of patients with moderately active ileocaecal Crohn's disease.16–18 However, even mesalazine may cause rash, headache, nausea, diarrhoea, pancreatitis, or blood dyscrasias in up to 5% of patients; interstitial nephritis occurs in around 1 in 500.19

Antibiotics

Metronidazole alone3,4 or with ciprofloxacin20 is moderately effective in active Crohn's disease. Treatment is given for up to 3 months but may be complicated by nausea, an unpleasant taste, alcohol intolerance, and a peripheral neuropathy, which can be irreversible. Preliminary reports have suggested possible therapeutic roles for ciprofloxacin, clarithromycin, rifabutin, and clofazimine, singly or in combination,3,4 but conventional antituberculous triple therapy is ineffective.21

Immunosuppressive drugs

For patients refractory to, or dependent on, corticosteroids, who because of extensive disease or previous resection need to avoid surgery, adjunctive azathioprine (2-2.5 mg/kg/day) or 6-mercaptopurine (1-1.5 mg/kg/day) remain invaluable, the dose of steroids being tapered as improvement occurs.22 Response to the thiopurines may take up to 4 months, but hopes that intravenous azathioprine could be used to accelerate improvement have not been confirmed by a controlled trial.23 Homozygous deficiency of 6-thiopurine methyltransferase, the enzyme responsible for the safe metabolic disposal of purine analogues, occurs in about 0.2% of people and may predispose to azathioprine's occasionally serious side effects (bone marrow depression,24 acute pancreatitis, chronic hepatitis). Routine assay of 6-thiopurine methyltransferase is not yet available but in the future may help identify patients at particular risk. The British National Formulary recommends that patients starting a thiopurine require blood counts every week for the first 8 weeks of treatment and at least every 3 months thereafter. Existing data about the risk of malignancy in patients with Crohn's disease given thiopurines long term are reassuring.25 It is not yet clear how long azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine should be used in Crohn's disease. However, in patients maintained in remission on a thiopurine the risk of relapse after 4 years seems to be similar whether the drug is continued or stopped.26

Methotrexate 25 mg intramuscularly weekly improves symptoms and reduces steroid requirements in about 40% of patients with chronically active steroid dependent Crohn's disease,27 but its side effects (bone marrow depression, hepatic fibrosis, pneumonitis, opportunistic infections) restrict its use to patients with very refractory disease. A lower oral dose (12.5 mg weekly) may also have a beneficial effect and prove safer.28 Patients given methotrexate need blood monitoring as for azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine; the necessity for routine lung function tests, chest x ray, or liver biopsy is not clear.

Cyclosporin has not been confirmed as useful in ileocaecal Crohn's disease.3 However, data from an unblinded controlled trial show that mycophenolate mofetil, an immunosuppressive drug that inhibits purine synthesis in lymphocytes, produces a quicker response than azathioprine in patients taking steroids with active Crohn's disease, with few adverse effects29: this report requires confirmation in a double blind controlled study.

Antitumour necrosis factor α antibody

The first specific cytokine related therapy to reach clinical application in Crohn's disease is infliximab, a mouse-human chimeric antibody (cA2) to tumour necrosis factor α; this preparation was launched in the United States in late 1998 and in the United Kingdom in September 1999.30,31

In patients with Crohn's disease refractory to steroids or conventional immunosuppressive drugs a single infusion of infliximab at 4 weeks produced improvement in 64% of patients and remission in 33% compared with 17% and 4% respectively after placebo.30 Relapse tended to occur in the ensuing months: repeated infusions at 4-8 weeks may produce more lasting remissions.32

Infliximab is infused intravenously over 2 hours—each 5 mg/kg infusion costs about £1000. Infusion reactions occur in up to 20% of patients and mean that treatment should be given in hospital, albeit on a daycare basis, where full resuscitation facilities are available. Common minor side effects include headache, nausea, and upper respiratory tract infections. Serious, although not opportunistic, infections including salmonella enterocolitis, pneumonia, and cellulitis have been reported. The production of human antichimeric antibodies may cause delayed hypersensitivity reactions (arthralgia, fever, rash) in patients given a repeat infusion after an interval of 2 or more years; anti-double stranded DNA and cardiolipin antibodies may cause a lupus syndrome. Rapid healing and fibrosis of intestinal strictures may precipitate obstruction. Lastly, there are reports of lymphoma in patients given infliximab for Crohn's disease and rheumatoid arthritis, although it is not yet clear if these are a complication of the disease or due to the drug.

In the future, selection of patients to be treated with antitumour necrosis factor α antibody may depend on their genotype as well as disease phenotype: patients with particular tumour necrosis factor microsatellite haplotypes, for instance, may respond poorly to infliximab.33 At present, because of uncertainties about its efficacy, safety and, cost-benefit ratio antitumour necrosis factor α antibody should be restricted to patients with very refractory inflammatory disease.

Possible new treatments

The place of other new approaches specifically targeting steps in the inflammatory process awaits clarification. Possible treatments include bone marrow transplant, lymphapheresis, antiCD4 and cellular adhesion molecule antibodies, interleukin 10, interleukin 11, and antisense oligonucleotides to nuclear transcription factors.34–37

Dietary therapy

In patients with a poor response to, or preference for avoiding, corticosteroids, and particularly in children, a liquid formula diet is a valuable option. Elemental (amino acid based), oligomeric (containing peptides), and polymeric (containing whole protein) feeds all approach the efficacy of corticosteroids if taken for 4-6 weeks as the sole nutritional source.38 The usefulness of enteral therapy is unfortunately limited by its cost, the difficulty many patients have in adhering to it, the need often to give the feed by nasogastric tube or percutaneous gastrostomy, and the high relapse rate that follows its discontinuation.10,38

Surgery

Surgery is usually indicated for patients whose ileocaecal disease fails to respond to drug or dietary therapy. Resection is not curative: there is a 50% chance of recurrence requiring further surgery at 10 years. Some patients prefer surgery at presentation to pharmacological or nutritional treatment of indefinite duration, but there are no controlled data to confirm the best approach. Although right hemicolectomy and stricturoplasty can both now be undertaken laparoscopically trials are required to compare open and laparoscopic surgery in this setting.39

Principles of treatment of active ileocaecal disease

General measures

Explanation, multidisciplinary care

Nutritional support

Drugs—antidiarrhoeals, haematinics, heparin (inpatients); avoid non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

Specific pharmacological options

Intravenous corticosteroids then tapered oral prednisolone or budesonide

High dose mesalazine

Metronidazole alone or with ciprofloxacin

Azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine (steroid non-responders)

Methotrexate (thiopurine and steroid non-responders)

Antitumour necrosis factor α antibody (thiopurine and steroid non-responders)

Nutritional therapy

Liquid formula diet

Endoscopic treatment

Balloon dilatation of strictures

Surgery

Resection or stricturoplasty

Treatment of other common presentations of active Crohn's disease

Obstructive small bowel disease

A raised platelet count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, or C reactive protein concentration,5 and a positive radiolabelled leucocyte scan may distinguish active from fibrostenotic Crohn's disease, but usually a trial of intravenous corticosteroids is given. Parenteral nutrition is required if resumption of eating is unlikely within a week. Although patients not settling after 48-72 hours of conservative treatment usually need surgery, short upper jejunal, terminal ileal, or colonic strictures can now be treated by enteroscopic or colonoscopic balloon dilatation40; the value of concomitant intralesional injection of triamcinolone is uncertain.41

Intra-abdominal abscess

Ultrasound and computed tomography are now used not only diagnostically but also to drain abscesses percutaneously. In patients whose abscesses have no enteric connection, this approach can obviate surgery.6

Intestinal fistula

Where there is no obstruction distal to the site of the fistula, enteral or parenteral nutrition, an oral thiopurine, or intravenous cyclosporin or antitumour necrosis factor α antibody cause some fistulae to heal.3,22,31 Many patients, however, still require surgical resection of the fistula and involved intestine.

Perianal disease

Non-suppurative perianal Crohn's disease may respond to oral metronidazole or ciprofloxacin, or both, given for up to 3 months3,4 and to long term thiopurine.22 Successful healing of perianal fistulae was reported in 62% of patients treated with three intravenous infusions over 6 weeks of antitumour necrosis factor α antibody compared with 26% of those given placebo.31 Although reopening of fistulae was common in the 3 months after treatment was stopped, antitumour necrosis factor α antibody may prove a useful advance in patients with refractory perianal disease. Patients with suppurating perianal Crohn's disease need surgery, minimised as far as possible: abscesses are drained and loose (seton) sutures inserted to facilitate the continued drainage of chronic fistulae.42

Crohn's colitis

Medical treatment of active Crohn's colitis resembles that of active ulcerative colitis. Oral or, in ill patients, intravenous corticosteroids remain the mainstay of treatment. Colonic release formulations of budesonide are under development. Oral aminosalicylates, including sulphasalazine, are an alternative in patients not acutely ill.3,4 In contrast with ulcerative colitis about 50% of patients with moderately active Crohn's colitis respond to oral metronidazole for up to 3 months,3 but there are no data about the efficacy of cyclosporin. Compliant patients with Crohn's colitis, like ileitis, may respond to a liquid formula diet.38

In patients who require total panproctocolectomy permanent ileostomy is usually preferred to ileoanal pouch because of a high incidence of pouch breakdown and sepsis in Crohn's disease. However, a recent series suggests that ileoanal pouches may be viable in patients with Crohn's disease without perianal or small bowel disease.43

Current management of other common presentations of Crohn's disease

Subacute obstruction

Intravenous corticosteroids, fluids, nasogastric suction

Endoscopic balloon dilatation (if accessible)

Surgery

Intra-abdominal abscess

Antibiotics

Percutaneous drainage

Surgery

Intestinal fistula

Enteral or parenteral nutrition

Azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, or intravenous cyclosporin

Antitumour necrosis factor α antibody

Surgery

Perianal disease

Metronidazole or ciprofloxacin, or both

Azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine

Antitumour necrosis factor α antibody

Surgery

Colitis

Corticosteroids

Aminosalicylates

Metronidazole

Liquid formula diet

Surgery

Maintenance of remission of Crohn's disease

The most effective prophylactic measure in patients who smoke is to stop: the risk of relapse in non-smokers at 5 years is about 30% lower than in smokers.2 The efficacy of drug prophylaxis is limited and depends on whether remission has been achieved by medical or surgical treatment.

Patients in remission after medical treatment

Meta-analysis shows that, unlike in ulcerative colitis, long term aminosalicylates have little or no prophylactic effect in this setting.44 Prednisolone in safe doses has no routine prophylactic role.3,4 Unfortunately long term budesonide (6 mg/day), although less likely to cause steroid related complications, delays time to relapse without increasing the remission rate at 1 year.45,46 Thiopurines are of proved value in maintaining remission and reducing steroid requirements in the minority of patients dependent on long term corticosteroids in whom symptoms recur whenever their dose is reduced.22

High potency ileal release fish oil capsules (Purepa), if commercially available, would be an attractive option should their prophylactic efficacy in one study47 be confirmed.

Patients in remission after surgical treatment

Long term aminosalicylates (at least 3 g/day mesalazine) reduce the risk of symptomatic relapse after resection by less than 15%.44 Oral budesonide (6 mg/day) halves endoscopic, although not symptomatic, recurrence rate at 1 year after resection for active but not fibrostenotic Crohn's disease.48 Oral metronidazole given for 3 months postoperatively reduces symptomatic as well as endoscopic recurrence rate at 1 year although not over a longer period49: it may be a useful option in patients reluctant to take drugs long term.

Maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease

Remission achieved medically

Stop smoking

Azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine (patients dependent on steroids)

Remission achieved surgically

Stop smoking

Mesalazine

Metronidazole (3 months only)

The future

Advances in medical treatment are likely to take several directions. Efforts are being made to formulate corticosteroids, aminosalicylates, and azathioprine in ways that focus delivery more accurately to the site of the disease. Our improved understanding of the aetiopathogenesis of Crohn's disease will lead to the development of further drugs, of which antitumour necrosis factor α antibody has been the first to reach the bedside, that are selectively targeted at specific points in the inflammatory pathway. The choice of treatment will depend increasingly not only on the phenotypic expression of patients' disease but also on their genotype. Finally, gene therapy, for example, applied topically to inflamed gut mucosa is an imminent possibility.

In view of the increasing variety and complexity of therapeutic options it will be essential to ensure that the patient remains at the centre of the decision making process as the fully informed and final arbiter of the type of treatment he or she is to be given.

Table.

Usefulness of imaging techniques for assessment of Crohn's disease

| Information obtained

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Site | Activity | Complications* | |

| Conventional radiology: | |||

| Plain abdominal film | + | + | − |

| Barium follow through | ++ | ++ | + |

| Ileocolonoscopy and biopsy | ++ | ++ | + |

| Newer imaging techniques: | |||

| Radiolabelled leucocyte scan | + | ++ | + |

| Ultrasound | + | − | + |

| Computed tomography | + | − | ++ |

| Magnetic resonance imaging | − | − | ++ |

Abscess, fistula, perianal disease.

Acknowledgments

The address of the National Association for Colitis and Crohn's Disease is 4 Beaumont House, Sutton Road, St Albans, Herts AL1 5HH.

Footnotes

Competing interests: DSR has received grants from Astra, Ferring, GlaxoWellcome, Janssen-Cilag, Pharmacia-Upjohn, Roche, SmithKline Beecham, and Wyeth for recruiting patients to clinical trials (none relevant to this review), for self initiated pathophysiological studies, for giving non-promotional lectures, and for travel to international meetings.

References

- 1.Fiocchi C. Inflammatory bowel disease: aetiology and pathogenesis. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:182–205. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70381-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cosnes J, Carbonnel F, Beaugerie L, Le Quintrec Y, Gendre JP. Effects of cigarette smoking on the long-term course of Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:424–431. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8566589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanauer SB, Meyers S. Management of Crohn's disease in adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:559–566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hanauer SB. Inflammatory bowel disease. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:841–848. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199603283341307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hodgson HJF. Laboratory markers of inflammatory bowel disease. In: Allan RN, Rhodes JM, Hanauer SB, Keighley MF, Alexander-Williams J, Fazio VW, editors. Inflammatory bowel diseases. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1997. pp. 329–334. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wills JS, Lobis IF, Denstman FJ. Crohn's disease: state of the art. Radiology. 1997;202:597–610. doi: 10.1148/radiology.202.3.9051003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sachar DB. Cancer in Crohn's disease: dispelling the myths. Gut. 1994;35:1507–1508. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.11.1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhatti M, Chapman P, Peters M, Haskard D, Hodgson HJF. Visualising E-selectin in the detection and evaluation of inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 1998;43:40–47. doi: 10.1136/gut.43.1.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haggett PJ, Moore NR, Shearman JD, Travis SPL, Jewell DP, Mortensen NJ. Pelvic and perineal complications of Crohn's disease: assessment using magnetic resonance imaging. Gut. 1995;36:407–410. doi: 10.1136/gut.36.3.407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lennard-Jones JE. Practical management of the short bowel. Aliment Pharmacol Therap. 1994;8:563–579. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.1994.tb00332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thromboembolism Risk Factors (THRIFT) Consensus Group. Risk of and prophylaxis for venous thromboembolism in hospital patients. BMJ. 1992;305:567–574. doi: 10.1136/bmj.305.6853.567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaufmann HJ, Taubin HL. Non steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs activate quiescent inflammatory bowel disease. Ann Intern Med. 1987;107:513–516. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-107-4-513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feagan BG, McDonald JWD, Koval JJ. Therapeutics and inflammatory bowel disease: a guide to the interpretation of randomised controlled trials. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:275–283. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8536868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rutgeerts P, Lofberg R, Malchow H, Lamers C, Olaison G, Jewell D, et al. A comparison of budesonide with prednisolone for active Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:842–845. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199409293311304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Campieri M, Ferguson A, Doe W, Persson T, Nilsson LG. Oral budesonide is as effective as oral prednisolone in active Crohn's disease. Gut. 1997;41:209–214. doi: 10.1136/gut.41.2.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thomsen OO, Cortot A, Jewell DP, Wright JP, Winter T, Veloso FT, et al. A comparison of budesonide and mesalamine for active Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:370–374. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199808063390603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singleton JW, Hanauer SB, Gitnick GL, Peppercorn MA, Robinson MG, Wruble LD, et al. Mesalamine capsules for the treatment of active Crohn's disease: results of a 16-week trial. Gastroenterology. 1993;104:1293–1301. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90337-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tremaine WJ, Schroeder KW, Harrison JM, Zinsmeister AR. A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of the oral mesalamine (5-ASA) preparation, Asacol, in the treatment of symptomatic Crohn's colitis and ileocolitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1994;19:278–282. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199412000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World MJ, Stevens PE, Ashton MA, Rainford DJ. Mesalazine-associated interstitial nephritis. Nephrol Dialysis Transplant. 1996;11:614–621. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.ndt.a027349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prantera C, Zannoni F, Scribano ML, Berto E, Andreoli A, Kohn A, et al. An antibiotic regimen for the treatment of active Crohn's disease: a randomised, controlled clinical trial of metronidazole plus ciprofloxacin. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:328–332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thomas GA, Swift GL, Green JT, Newcombe RG, Braniff-Mathews C, Rhodes J, et al. Controlled trial of anti-tuberculous chemotherapy in Crohn's disease: a five year follow up study. Gut. 1998;42:497–500. doi: 10.1136/gut.42.4.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pearson DC, May GR, Fick GH, Sutherland LR. Azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine in Crohn's disease: a meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122:132–142. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-123-2-199507150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sandborn WJ, Tremaine WJ, Wolf DC, Targan SR, Sninsky CA, Sutherland LR, et al. Lack of effect of intravenous administration on time to respond to azathioprine for steroid-treated Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:527–535. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70445-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Connell WR, Kamm MA, Ritchie JK, Lennard-Jones JE. Bone marrow toxicity caused by azathioprine in inflammatory bowel disease: 27 years of experience. Gut. 1993;34:1081–1085. doi: 10.1136/gut.34.8.1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Connell WR, Kamm MA, Dickson M, Balkwill AM, Ritchie JK, Lennard-Jones JE. Long term neoplasia risk after azathioprine treatment in inflammatory bowel disease. Lancet. 1994;343:1249–1252. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)92150-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bouhnik Y, Lémann NM, Mary JY, Scemama G, Tai R, Matuchansky C, et al. Long term follow up of patients with Crohn's disease treated with azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine. Lancet. 1996;347:215–219. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)90402-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feagan BG, Rochon JR, Fedorak RN, Irvine EJ, Wild G, Sutherland L, et al. Methotrexate for the treatment of Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:292–297. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199502023320503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oren R, Moshkowitz M, Odes S, Becker S, Keter D, Pomeranz I, et al. Methotrexate in chronic active Crohn's disease: a double-blind, randomised, Israeli multi-centre trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:2203–2209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Neurath MF, Wanitschke R, Peters M, Krummenauer F, Meyer zum Büschenfelde K-H, Schlaak JF. Randomised trial of mycophenolate mofetil versus azathioprine for treatment of chronic active Crohn's disease. Gut. 1999;44:625–628. doi: 10.1136/gut.44.5.625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Targan SR, Hanauer SB, van Deventer SJH, Mayer L, Present DH, Braakman T, et al. A short-term study of chimeric monoclonal antibody cA2 to tumour necrosis factor alpha for Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1029–1035. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199710093371502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Present DH, Rutgeerts P, Targan S, Hanauer SB, Mayer L, van Hogesand RA, et al. Infliximab for the treatment of fistulas in patients with Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1398–1405. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199905063401804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rutgeerts P, D'Haens G, Targan S, Vasiliauskas E, Hanauer SB, Present DH, et al. Efficacy and safety of retreatment with anti-tumour necrosis factor antibody (Infliximab) to maintain remission in Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:761–769. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70332-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Plevy SE, Taylor K, DeWoody KL, Schaible TF, Shealy D, Targan SR. Tumour necrosis factor micro-satellite haplotypes and perinuclear anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (pANCA) identify Crohn's disease patients with poor clinical responses to anti-TNF monoclonal antibody (cA2) Gastroenterology. 1997;112:A1062. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lopez-Cupero SO, Sullivan KM, McDonald GB. Course of Crohn's disease after allogeneic marrow transplantation. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:433–440. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70525-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bickston SJ, Cominelli F. Inflammatory bowel disease: short- and long-term treatments. Adv Intern Med. 1998;43:143–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Van Deventer SJH, Elson CO, Fedorak RN. Multiple doses of intravenous interleukin-10 in steroid-refractory Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:383–389. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v113.pm9247454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Neurath MF, Pettersson S, Meyer zum Büschenfelde K-H, Strober W. Local administration of antisense phosphothiolate oligonucleotides to the p65 subunit of NF-kB abrogates established experimental colitis in mice. Nature Med. 1996;2:998–1004. doi: 10.1038/nm0996-998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Griffiths AM, Ohlsson A, Sherman PM, Sutherland LR. Meta-analysis of enteral nutrition as a primary therapy of active Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:1056–1067. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90203-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ogunbiyi OA, Fleshman JW. Place of laparoscopic surgery in Crohn's disease. Baillière's Clin Gastroenterol. 1998;12:157–165. doi: 10.1016/s0950-3528(98)90090-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Couckuyt H, Gevers AM, Coremans G, Hiele M, Rutgeerts P. Efficacy and safety of hydrostatic balloon dilatation of ileocolonic Crohn's strictures: a prospective longterm analysis. Gut. 1995;36:577–580. doi: 10.1136/gut.36.4.577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lavey A. Triamcinolone improves outcome in Crohn's disease strictures. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:184–186. doi: 10.1007/BF02054985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kodner IJ. Perianal Crohn's disease. In: Allan RN, Rhodes JM, Hanauer SB, Keighley MF, Alexander-Williams J, Fazio VW, editors. Inflammatory bowel diseases. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1997. pp. 863–872. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Panis Y, Poupard B, Nemeth J, Lavergne A, Hautefeuille P, Valleur P. Ileal pouch/anal anastomosis for Crohn's disease. Lancet. 1996;347:854–857. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)91344-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cammà C, Giunta M, Rosselli M, Cottone M. Mesalazine in the maintenance treatment of Crohn's disease: a meta-analysis adjusted for confounding variables. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:1465–1473. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v113.pm9352848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Greenberg GR, Feagan BG, Martin F, Sutherland LR, Thomson ABR, Williams CN, et al. Oral budesonide as maintenance treatment for Crohn's disease: a placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:45–51. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8536887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lofberg R, Rutgeerts P, Malchow H, Lamers C, Danielsson Å, Olaison G, et al. Budesonide prolongs time to relapse in ileal and ileocaecal Crohn's disease. A placebo-controlled one year study. Gut. 1996;39:82–86. doi: 10.1136/gut.39.1.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Belluzi A, Brignola C, Campieri M, Pera A, Boschi S, Miglioli M. Effect of an enteric-coated fish-oil preparation on relapses in Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1557–1560. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199606133342401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hellers G, Cortot A, Jewell DP, Leijonmarck CE, Löfberg R, Malchow H, et al. Oral budesonide for prevention of post surgical recurrence in Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:294–300. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70125-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rutgeerts P, Hiele M, Geboes K, Peeters P, Penninckx F, Aerts R, et al. Controlled trial of metronidazole treatment for prevention of Crohn's recurrence after ileal resection. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:1617–1621. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90121-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]