In surveys of users of complementary medicine, about 80% are satisfied with the treatment they received. Interestingly, this is not always dependent on an improvement in their presenting complaint. For example, in one UK survey of cancer patients, changes attributed to complementary medicine included being emotionally stronger, less anxious, and more hopeful about the future even if the cancer remained unchanged.

Satisfaction may influence further use of complementary medicine: a Community Health Council survey found that over two thirds of complementary medicine users returned for further courses of treatment and that over 90% thought that they might use complementary medicine in the future. What is it that patients find worth while and what does this tell us about their expectations of healthcare services in general?

Attraction of complementary medicine

The specific effects of particular therapies obviously account for a proportion of patient satisfaction, but surveys and qualitative research show that many patients also value some of the general attributes of complementary medicine. These may include the relationship with their practitioner, the ways in which illness is explained, and the environment in which they receive treatment. When these augment the therapeutic outcome of treatment, they contribute to what is sometimes called “the placebo effect.” None of these is unique to complementary medicine, but many are facilitated by the private, non-institutional settings in which most complementary practitioners work. The relative therapeutic importance of specific and non-specific attributes obviously depends on individual patients and practitioners, but some complementary practitioners may be better than their conventional colleagues at using and maximising “the placebo effect.”

Time and continuity

Patients often cite the amount of time available for consultation as a reason for choosing complementary medicine, and contrast this with their experiences of seeing conventional NHS doctors. This is partly a feature of all private medicine, but even when complementary practitioners work in the NHS their first appointments tend to be up to an hour long in order to take the detailed case history that diagnosis and treatment requires.

Particularly when the problem is chronic and multifactorial, this type of consultation, in which patients are encouraged to explain their experience and understanding of their problem, can itself be therapeutic. Patients also generally see the same complementary practitioner over their course of treatment, and this continuity further facilitates the development of a therapeutic patient-practitioner relationship.

Attention to personality and personal experience

All healthcare practitioners, conventional or complementary, aim to tailor their interventions to the needs of individual patients. However, conventional practitioners generally direct treatment at the underlying disease processes, whereas many complementary practitioners base treatment more on the way patients experience and manifest their disease, including their psychology and response to illness. Treatment is “individualised” in both cases, but patients' personalities and emotions may be more influential in the latter approach.

Although good conventional care involves considering the patient as a person, not a disease, time pressures can lead to an apparent emphasis on the physical aspects of illness. Some patients cite the lack of personal attention paid by conventional practitioners as a reason for choosing a complementary approach. The quality of personal attention is obviously influenced by time and continuity as described above.

Patient involvement and choice

Some users cite the increased opportunities for active participation in the process of recovery as a reason for choosing complementary medicine. Although self help measures are increasingly part of conventional healthcare advice, patients feel that complementary practitioners give this greater emphasis.

Patients also value being able to choose a complementary therapist or therapy which suits them. To some extent, this is true of all private sector health care, but it is also possible when a choice of different complementary approaches is available on the NHS. An example would be the range of complementary therapies available in many hospices.

Hope

Patients often come to complementary medicine after having tried everything that conventional medicine has to offer. Complementary practitioners can offer hope to such patients, both by attempting to influence the underlying disease and, often more importantly, by addressing emotional states, energy levels, coping styles, and other aspects that contribute to quality of life. This is particularly important for patients with chronic diseases and no prospect of cure from conventional medicine. However, practitioners need to balance their claims carefully, considering the realistic chances of improvement and the dangers of creating false hope and further disappointment.

Touch

Many complementary treatments and diagnostic techniques involve more physical contact between patients and practitioners than is usual in conventional medicine. Touch can facilitate more open and honest communication, and patients may turn to the “low tech” consulting rooms of aromatherapists and reflexologists for a less distancing and more human experience of health care.

Attitudes to touch through massage

Staff member in learning difficulties unit—“People with profound disabilities often become isolated from any special caring touch. It's inappropriate for us to go around hugging and cuddling pupils, but we can use hand and foot massage”

Cancer patient—“They're too busy, the nurses, ... rushing round the wards .... With massage, as soon as the hands go on, you know she's there, she's calm, she's touching you, she has time for you”

Patient in primary care—“Touch had never been common in my family. Massage has been complementary in giving me a structured experience of touch. The main benefit, though, was relearning to be at ease with my body, relax my mind, without being overcome with weeping or anxieties”

Example of a complementary practitioner's view of illness

A patient with chronic ear infections consulted a complementary practitioner, who associated his problem with bad dietary habits and longstanding digestive problems:

“She said that, from a holistic point of view, if you cannot eliminate in the normal way, where does the residual muck go? It can go into your eyes, your breath, and your ears. And, lo and behold, I realised it. She said I was excreting rubbish through my ears, and this, of course, fitted into place, because it was black and sticky. No one ever told me that; they just said, ‘You’re producing too much wax'”

Taken from Sharma 1995

Dealing with ill defined symptoms

Practitioners of modern Western medicine have become expert in recognising, identifying, and treating disease. When there is no organic disease present but simply ill defined symptoms or a general “lack of health” they may have less to offer. As a result, patients presenting with illnesses such as chronic fatigue, functional back pain, or irritable bowel syndrome may feel that their doctor does not take their symptoms seriously or does not really believe that they are ill. Complementary practitioners do not need a conventional diagnosis to initiate treatment; in fact, many think that their treatments are most effective in patients without organic pathology. (The risks of missing serious conditions if complementary treatments are given to patients without definite diagnoses are considered in the next article.)

Making sense of illness

Patients often want to incorporate their experience of illness into their understanding of themselves and their world. They ask questions like “Why has this happened to me?” and “What in my life has caused my problem?” Complementary practitioners may have explanations that make sense to patients—such as describing illness as a result of environmental factors or as a physical expression of emotional patterns.

Conventional medicine may have problems with such explanations if they have no scientific justification, but sociological research shows that patients consider them beneficial when they reinforce their own beliefs and expectations. Sometimes the explanations given by complementary practitioners can cause problems—for example, if illness is attributed to childhood vaccinations or patients are made to feel guilty for past behaviour.

Spiritual and existential concerns

Some patients have existential concerns that conventionally trained professionals may not feel competent to address. These range from the otherwise healthy adolescent who can find no meaning or purpose in life to the terminally ill patient confronting his or her own mortality. Many complementary disciplines make no distinction between spiritual symptoms and any other types of symptom and offer treatments aimed at this aspect of a person's life or illness.

Concern over complementary medicine

The general attributes of complementary medicine do not always lead to increased patient satisfaction. Complementary medicine has some features that can cause patients problems or produce negative effects. Those that primarily involve patients' practical or emotional responses are described below. Those that may pose risks to patients' overall healthcare are covered in the next article.

Safety and competence

There is public anxiety that some complementary practitioners may not be adequately qualified, although patients who have already used complementary medicine show less concern. Patients' inability to trust in the competence of their complementary practitioner will influence their experience of treatment. The lack of nationally recognised professional standards for some therapies is a major problem.

Potential for inducing guilt and blame in complementary medicine literature

Louise Hay—“All disease comes from a state of unforgiveness”

Edward Bach—“Rigidity of mind will give rise to those diseases which produce rigidity and stiffness of the body”

Alexander Lowen—“A weakness in the backbone must be reflected in serious personality disturbance ... the individual with sway back cannot have the ego strength of a person whose back is straight”

Patients often make assumptions about the safety of complementary medication bought over the counter. As many of these contain pharmacologically active agents, they have the potential for adverse effects, particularly where they are taken in combination with other complementary or conventional medication.

Guilt

One potential danger of empowering patients to play an active part in improving their health is that some come to believe that they are solely responsible for their ill health or lack of recovery. For example, patients who are encouraged to take a positive attitude in fighting cancer can suffer increased distress if they infer that their illness is a product of an excessively negative personality. Complementary practitioners need to be aware of this potential when giving advice and explanations to vulnerable patients.

Denial

Some patients continue to try different complementary therapies even though none has given any relief. This behaviour can promote an unhelpful pattern of denial about a condition. Repeated attempts to find a cure through complementary medicine can prevent appropriate acceptance and adjustment. Complementary practitioners need to be aware of the risks of colluding with this behaviour.

Blame

Some of the explanations given by complementary practitioners emphasise external and environmental causes of illness. For example, they may claim a disease is caused by vaccinations, conventional drugs, drinking water, dental fillings, or pollution. Placing the blame for ill health solely on external factors that cannot easily be altered may lead to patients feeling victimised, disempowered, and bitter. There may be other factors influencing their illness, and helpful coping strategies, that could be more usefully addressed.

Further reading

Benson H. Timeless healing; the power and biology of belief. London: Simon and Schuster 1996

Bishop B. A time to heal. 2nd ed. London: Arkana, 1996

Sharma U. Complementary medicine today: practitioners and patients. Rev ed. London: Routledge, 1995

Financial risk

The amount of money some patients spend on complementary medicine is considerable. Costs vary widely, and higher prices do not necessarily mean better or more effective treatment. The lack of evidence concerning many complementary interventions means that the likelihood of a successful outcome is often impossible to predict. Patients should be aware of this risk. They should also be encouraged to ask practitioners, and seek guidance from the main regulatory bodies, about estimated costs for a complete course of treatment, including tests and medications, before starting complementary therapy.

Social factors

Most users of complementary medicine in Britain are of middle to high socioeconomic status. Possibly as a result, the effects of poverty, poor housing, and discrimination are underplayed in complementary accounts of disease causation.

Figure.

Increasing availability of and demand for complementary medicine is evidence of its popularity. The question is whether this represents a passing fashion or a deeper need for change within the healthcare system

Figure.

Patients seem to appreciate the time and attention they receive during a complementary medicine consultation

Figure.

Whereas a doctor may be primarily interested in diagnosing atopic dermatitis from other skin conditions, complementary practitioners often take as much account of personality and emotions as they do of physical signs and symptoms

Figure.

“Prostate Roar” by Ian Summers (1998), painted during art therapy after his prostate cancer had been diagnosed. Art therapy, like many complementary therapies, can help patients to construct a meaningful narrative of disease

Figure.

Aromatherapy massage in a hospice. Many forms of complementary medicine involve physical contact with patients

Figure.

Conventional medicine may leave patients' spiritual and existential concerns unmet

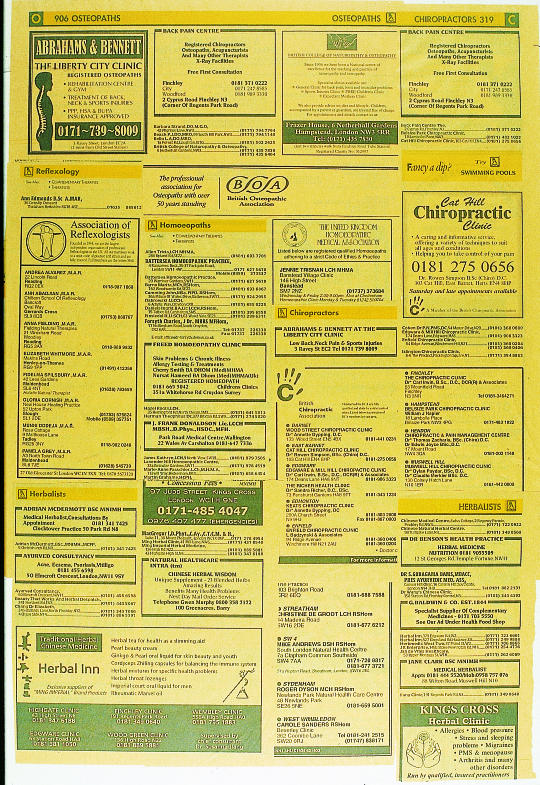

Figure.

It is often difficult to assess the training and competence of complementary practitioners

Acknowledgments

The picture of a health food shop is reproduced with permission of Holland and Barrett. The picture of acupuncture is reproduced with permission of the Royal London Homoeopathic Hospital. The picture of eczematous hands is reproduced with permission of the National Medical Slide Bank. “Prostate Roar” is reproduced with permission of the University of Pennsylvania Cancer Center. The picture of aromatherapy is reproduced with permission of John Cole/ Impact. The picture of a hospital patient is reproduced with permission of Tony Stone Images/Adam Hinton.

Footnotes

The ABC of complementary medicine is edited and written by Catherine Zollman and Andrew Vickers. Catherine Zollman is a general practitioner in Bristol, and Andrew Vickers is a research methodologist at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York. At the time of writing, both worked for the Research Council for Complementary Medicine, London. The series will be published as a book in spring 2000.