Abstract

Glioblastoma is the most common malignant primary brain tumor. Despite its infiltrative nature, extra-cranial glioblastoma metastases are rare. We present a case of a 63-year-old woman with metastatic glioblastoma in the lungs. Sarcomatous histology, a reported risk factor for disseminated disease, was found. Genomic alterations of TP53 mutation, TERT mutation, PTEN mutation, and +7/-10 were also uncovered. Early evidence suggests these molecular aberrations are common in metastatic glioblastoma. Treatment with third-line lenvatinib resulted in a mixed response. This case contributes to the growing body of evidence for the role of genomic alterations in predictive risk in metastatic glioblastoma. There remains an unmet need for treatment of metastatic glioblastoma.

Keywords: : extra-neural glioblastoma, gliosarcoma, lenvatinib, metastatic glioblastoma, vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitor, VEGF

Plain language summary

Glioblastoma is the most common malignant primary brain tumor. Glioblastoma can spread into healthy tissue, but metastases beyond the brain are rare. We present a case of a 63-year-old woman with metastatic glioblastoma in the lungs. We identified risk factors associated with spread beyond the brain, including factors related to tissue structure and specific molecular alterations. Treatment with third-line lenvatinib resulted in a mixed response. This case adds to the limited existing data for the use of molecular alterations to serve as risk factors for metastatic glioblastoma. Treatment options are needed for this devastating disease.

TWEETABLE ABSTRACT

Despite the infiltrative nature of glioblastoma, extra-cranial metastases are rare. Sarcomatous histology and genomic alterations of TP53 mutation, TERT mutation, PTEN mutation, and +7/-10 are described as risk factors for the development of glioblastoma metastases. No effective treatments exist. In our metastatic glioblastoma patient, third-line lenvatinib resulted in a mixed response. #glioblastoma #metastaticglioblastoma #lenvatinib #VEGF #VEGFinhibitor.

Plain language summary

Executive Summary.

Metastatic glioblastoma is a rare phenomenon.

Risk factors for the development of metastatic glioblastoma include gliosarcoma, surgery, tumor recurrence and prolonged survival.

Preliminary evidence suggests that genomic alterations may play a potential role in predicting the risk of metastatic glioblastoma.

Treatment options for metastatic glioblastoma remains an unmet need.

Lenvatinib for glioblastoma is under investigation.

1. Background

Glioblastoma is the most commonly occurring malignant primary brain tumor [1]. Despite the infiltrative nature of glioblastoma, metastases are infrequent with an incidence of only 0.4–2.0% [2–5]. Accordingly, the rare detection of metastases has resulted in the forgoing of staging for glioblastoma [6]. However, cases are on the rise due to heightened awareness and evidence suggests that 20% of glioblastoma cases are found to have tumor-circulating cells [7–9]. Despite this finding, glioblastoma predominantly remains an intracranial disease [7–9]. There are several reasons for restricted disease dissemination beyond the brain [10]. First, shortened survival prior to the development of metastases has been postulated [10–12]. Second, the failure of tumor cells to proliferate in unfavorable extra-cranial ‘soil’ that lacks brain-specific growth factors may preclude the distal spread of glioblastoma cells [10–15]. Last, immunocompetency may drive circulating glioblastoma cells into dormancy and prohibit tumor development [16]. For the subset of cases in which metastases do occur, extra-cranial intra-neural drop metastases to the spine are more common than extra-neural dissemination to outside organs. Extra-neural glioblastoma metastases have been previously reported in the lung, liver, bone, lymph nodes, and spleen [12,17–25]. Prognosis remains especially poor with a median overall survival of 10.5 months and a median time from metastasis to death of 1.5 months [19]. We present a case of a 63-year-old woman with metastatic glioblastoma in the lungs. We examine possible risk factors, including genomic alterations, for the development of her extra-neural disease. We also describe her treatment response to lenvatinib monotherapy. Our case adds to the limited, but growing body of evidence supporting the early identification and prompt treatment for metastatic glioblastoma (Table 1).

Table 1. Extra-neural glioblastoma cases.

| Publication | Age/gender | Site of initial disease | EOR | Pre-metastases treatment | Site of metastases | Interval from Dx to metastases (months) | Sarcomatous component | Metastases treatment | Outcome and cause of death | Interval from metastasis to death | Interval from initial Dx to death | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yuen et al., 2024 (present case) | 63/F | L frontal | NTR | XRT, TMZ, BEV, CCNU | Lung | 8.5 | Y | Lenvatinib | PD | 1.5 | 10 | |

| Potter et al., 1983 | 41/M | L frontal | STR | WBRT | Submandible | 11 | NR | XRT, CCNU | SD at 9 month follow-up | – | – | [26] |

| Wallace et al., 1996 | 41/M | R frontal | GTR | XRT, BCNU | LN | NR | NR | XRT, chemo | Aspiration | NR | 8 | [27] |

| Beauchesne et al., 2000 | 54/M | R temporal | STR | XRT, etoposide | Heart, lung, bone | 7 | NR | – | – | 2 | 9 | [28] |

| Hübner et al., 2001 | 47/M | R cerebellum | NR | XRT, chemo | Neck and LN | 10 | NR | RT | PD | 7 | 17 | [29] |

| Allan et al., 2004 | 60/M | NR | STR | XRT | Scalp | 12 | NR | Steroids | NR | 2 | 14 | [30] |

| Ogungbu et al., 2005 | 49/F | R occipital | Resection | XRT, CCNU, procarbazine | Lung, parotid gland | 7 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 16 | [31] |

| Taha et al., 2005 | 33/M | L frontal | STR | XRT | Parotid gland | 6 | XRT, PCV | NR | PD | 3.5 | NR | [32] |

| Templeton et al., 2008 | 58/M | L frontal | GTR | XRT, TMZ | Epidural spine, lungs, bone, retroperitoneum | 5 | Y | Resection, XRT, TMZ | Metastases to soft tissue and spine and PE | 6 | 11 | [33] |

| 47/F | R frontal | STR | TMZ | Pleura | 24 | NR | – | Respiratory insufficiency | 24 | 24 | ||

| Zhen et al., 2010 | 25/M | R frontoparietal | GTR | Re-resection, XRT | Bone and LN | 2 | N | Chemo | NR | NR | NR | [34] |

| Armstrong et al., 2011 | 30/F | L frontal | STR | XRT, TMZ, sorafenib and erlotinib | Soft tissue scalp | NR | N | Irinotecan and bevacizumab | Stable for 11 months then metastases to bone | NR | NR | [35] |

| Kalokhe et al., 2012 | 72/M | R temporal and occipital | GTR | XRT, TMZ, BEV, BCNU | Lung, bone | 10 | NR | – | NR | 9 | 19 | [36] |

| 31/F | L cerebellum | GTR | Erlotinib, BEV | Bone | 4 | NR | RT, TMZ, BEV | PD | 5 | 9 | ||

| Seo et al., 2012 | 46/M | L frontoparietal | Resection | GKRS, PCV, TMZ | Cervical LN | 60 | NR | Resection and unspecified aggressive treatment | PD | 6 | 66 | [37] |

| Blume et al., 2013 | 40/M | R parasagittal | STR | XRT, TMZ | Lung, LN, bone, muscle, epidura | 36 | NR | STR, XRT, TMZ | NR | NR | NR | [38] |

| Dawar et al., 2013 | 57/F | R temporal | GTR | XRT, TMZ | Pre-auricular region | 51 | NR | Mesna, adriamycin, ifosfamide, gemcitabine, docetaxel, SRS | PD | 6.5 | 57.5 | [39] |

| Lettau et al., 2013 | 80/NR | L temporal | GTR | XRT and TMZ | Dura | 7 | NR | Resection | NR | NR | NR | [40] |

| Romero-Rojas et al., 2013 | 26/M | Frontal | NR | XRT, TMZ | Parotid gland, LN, bone | NR | NR | XRT, TMZ | NR | NR | NR | [41] |

| Undabeitia et al., 2015 | 20/F | R temporal | GTR | XRT, chemo | Lung | 5 | NR | – | – | 3 | 8 | [42] |

| Anghileri et al., 2016 | 30/M | L central sulcus | NR | XRT, RT, re-resection, BEV | Neck | 82 | No | – | PD | 1.5 | 83.5 | [7] |

| 43/M | L frontal | GTR | XRT, TMZ, BEV, re-resection | Subcutaneous | 23.5 | – | – | PD | 1.5 | 25 | ||

| Franceschi et al., 2016 | 70/M | NR | STR | NR | Lung, liver, bone | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | [43] |

| Lewis et al., 2017 | 47/F | L cerebellum | GTR | XRT, TMZ | Soft tissue and LM | NR | NR | CSI, TMZ, thymalfasin | Stable LMD, excision of subcutaneous mass | NR | NR | [44] |

| Semonetti et al., 2017 | 38/M | L parietal | GTR | XRT, TMZ, re-resection, BEV | Lung, LN, bone | 48 | NR | Etoposide, oncocarbide | Metastases to liver, intralesional hemorrhage, pleural effusion | NR | NR | [45] |

| Hori et al., 2018 | 75/F | L fronto-temporal, L BG and R frontal | STR | – | LN and pleura | 2.8 | NR | – | Respiratory failure | 0.3 | 3.4 | [46] |

| Janik et al., 2019 | 51/M | R temporal | GTR | XRT, TMZ | Lung | 3 | NR | – | NR | 3.5 | 22.5 | [47] |

| Tamai et al., 2019 | 49/M | R temporal | GTR | XRT, TMZ | Ventricle, dura, LM, lung | NR | NR | Resection, XRT, TMZ, BEV | Respiratory failure | NR | 12 | [48] |

| Houston et al., 2000 | 19/M | L parietal | STR | XRT, 125I brachytherapy | Bone | 16 | NR | RT, cisplatin, VP-16, MTX/adriamycin/vincristine/taxol | Recurrence | 1 | 17 | [49] |

| 32/M | L temporal | STR | XRT, BCNU, 125I brachytherapy | Scalp | 6 | Y | Excision | Recurrence | 6 | 13 | ||

| 36/F | Frontal | bx | XRT, 125I brachytherapy | Neck | 17 | NR | Procarbazine | PD | 9 | 26 | ||

| Hsu et al., 2020 | 53F | R temporo-parieto-occipital | NTR | PBRT, re-resection, Gliadel wafers, TMZ, BEV | Bone | 15 | Y | Resection | NR | NR | 20 | [50] |

| Liu et al., 2020 | 46/M | L temporal | GTR | XRT, TMZ | Scalp | 6 | NR | XRT, irinotecan, TMZ | Metastases to lung after 9 months | 14 | 20 | [2] |

| Rossi et al., 2020 | 29/F | R frontal | STR | Multiple resections, XRT, TMZ | Lymphatic and bone metastases | 39 | NR | XRT, procarbazine, CCNU | PD and sepsis | 12 | 48 | [51] |

| Umphlett et al., 2020 | 74/F | L occipital | Resection | XRT, TMZ, SRS | Lungs, heart, breast, liver, thyroid, bowel, bone, LN | 1 | N | – | – | NR | 12 | [52] |

| Sickler et al., 2021 | 57/M | R temporal | NTR | XRT, TMZ | Bone | 12 | N | XRT, TMZ | NR | NR | NR | [24] |

| Alsardi et al., 2022 | 43/F | R parasagittal | GTR | XRT, TMZ, atorvastatin, BEV, multiple resections, irinotecan, re-RT | Lung, LN | 59 | N | Carboplatin, etoposide | NR | NR | NR | [53] |

| Hersh et al., 2022 | 46/F | L parietal | STR | XRT, TMZ | Bone | 10 | NR | Percutaneous microwave ablation, vertebroplasty, palliative RT, chemo | NR | NR | NR | [23] |

| Kumaria et al., 2022 | 65/M | L temporal | STR | XRT, TMZ | Lung | 17 | NR | – | Respiratory failure | NR | NR | [54] |

| Nakib et al., 2022 | 53/M | R PLIC and thalamus | STR | XRT, TMZ, BEV, CCNU, irinotecan | Skin | 6 | N | BEV | Asystole | NR | NR | [55] |

BCNU: Carmustine; BEV: Bevacizumab; BG: Basal ganglia; Chemo: Chemotherapy; CCNU: Lomustine; CSI: Craniospinal irradiation; Dx: Diagnosis; EOR: Extent of resection; F: Female; GKRS: Gamma knife radiosurgery; GTR: Gross total resection; IFN-β: Interferon-β; LM: Leptomeninges; LMD: Leptomeningeal disease; LN: Lymph node; M: Male; NR: Not reported; NTR: Near total resection; PCV: Procarbazine, CCNU, vincristine; PD: Progressive disease; PLIC: Posterior limb of internal capsule; RT: Radiation therapy; SD: Stable disease; SRS: Stereotactic radiosurgery; STR: Subtotal resection; TMZ: Temozolomide; WBRT: Whole brain radiation therapy.

2. Case presentation

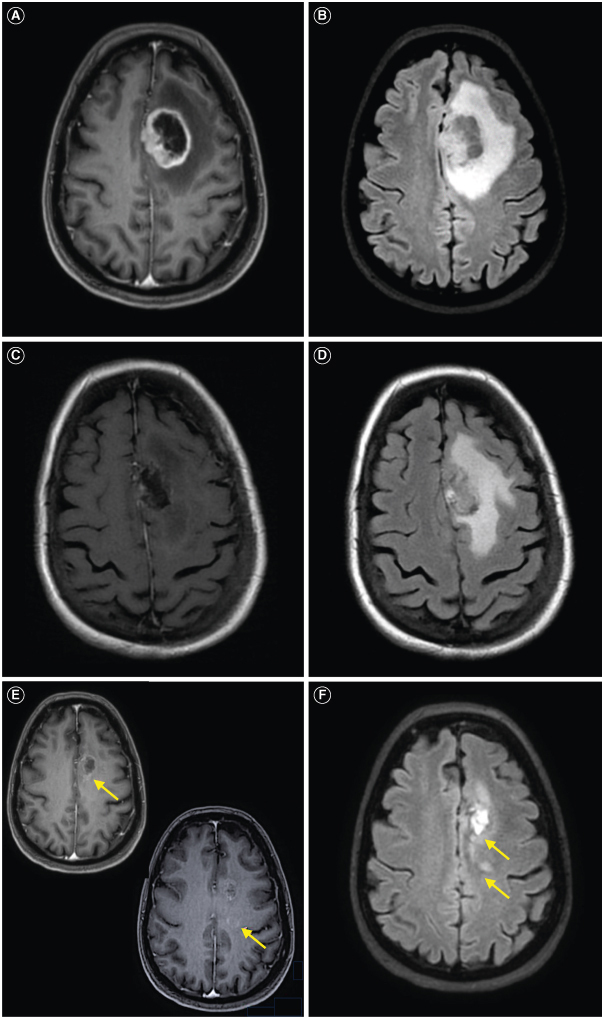

A 63-year-old female with a past medical history of hypertension presented with expressive aphasia secondary to a left frontal heterogeneously enhancing mass with surrounding vasogenic edema (Figure 1A & B). She underwent a left frontal craniotomy for tumor resection. Postoperative brain MRI demonstrated near total resection of her enhancing tumor and persistent vasogenic edema (Figure 1C & D).

Figure 1.

Patient's intracranial glioblastoma throughout the therapy course. (A) Preoperative axial T1 post-contrast brain MRI shows a left frontal heterogeneously enhancing mass. (B) Preoperative axial T2/FLAIR brain MRI shows surrounding vasogenic edema. (C) Postoperative axial T1 postcontrast brain MRI shows near total resection of the previously seen enhancing tumor. (D) Post-operative axial T2/FLAIR brain MRI shows persistent hyperintensity. (E) Radiation planning axial T1 post-contrast brain MRI shows interval development of contrast-enhancing lesions at the posterior margin of the resection cavity and posterior to the resection cavity (yellow arrows). (F) Radiation planning axial T2/FLAIR brain MRI shows hyperintensity associated with the new enhancing lesions. (G) Post-radiation axial T1 post-contrast brain MRI shows interval enlargement of the prior lesion posterior to the resection cavity. (H) Post-radiation T2/FLAIR axial brain MRI shows surrounding vasogenic edema. (I) Re-resection postoperative T1 postcontrast axial brain MRI shows near total resection of the prior enhancing mass. (J) Re-resection postoperative T2/FLAIR axial brain MRI shows improvement in the surrounding vasogenic edema. (K) Post 2 cycles of lomustine and 3 cycles of bevacizumab, T1 post-contrast axial brain MRI shows interval development of a contrast-enhancing mass. (L) Post 2 cycles of lomustine and 3 cycles of bevacizumab, T2/FLAIR axial brain MRI shows surrounding vasogenic edema. (M) Post 2 cycles of lomustine and 4 cycles of bevacizumab, T1 post-contrast axial brain MRI shows interval enlargement of the contrast-enhancing mass. (N) Post 2 cycles of lomustine and 4 cycles of bevacizumab, T2/FLAIR axial brain MRI shows surrounding vasogenic edema. (O) Post 10 days of lenvatinib, T1 post-contrast axial brain MRI shows an interval decrease in the previously seen contrast-enhancing mass. (P) Post 10 days of lenvatinib, T2/FLAIR axial brain MRI shows an interval decrease in the previously seen T2/FLAIR hyperintensity. (Q) Post 10 days of lenvatinib, DWI axial brain MRI shows associated abnormal signals with the aforementioned mass. (R) Post 10 days of lenvatinib, ADC axial brain MRI shows minimal ADC correlate along the lateral margin of the mass.

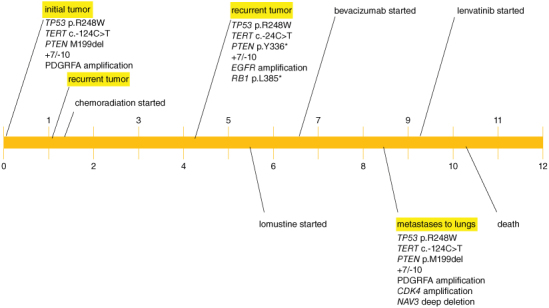

Histopathologic evaluation showed an IDH wildtype glioblastoma, WHO grade 4 with characteristic features of both necrosis and microvascular proliferation, which was MGMT unmethylated. Next-generation sequence analysis revealed mutations in TP53 (p.R248W), TERT promoter (c.-124C>T), PTEN (p.M199del), PDGFRA amplification and trisomy 7/monosomy 10 (+7/-10). Her radiation planning brain MRI demonstrated significant resolution of the prior vasogenic edema, but new contrast enhancement at the posterior margin of the resection and a minimally ring-enhancing mass posterior to the resection cavity with associated T2 FLAIR hyperintensity (Figure 1E & F). During her standard 6-week course of radiation (60 Gy) and chemotherapy (temozolomide 75 mg/m2), dexamethasone 4 mg twice daily was started for new right hemiparesis. Her post-radiation brain MRI with and without contrast showed a new 2.6 cm enhancing mass posterior to the resection cavity with surrounding vasogenic edema (Figure 1G & H) that was subsequently near totally resected with stable T2 FLAIR hyperintensity (Figure 1I & J). Histopathology confirmed residual/recurrent glioblastoma with giant cell features, and repeat sequencing showed mutations in TP53 (p.R248W), TERT promoter (c.-124T>C), PTEN (p.Y336*), RB1 (p.L385*), amplification of EGFR; and +7/-10 (Figure 2A & B). Second-line combination therapy was started with bevacizumab for steroid dependence and lomustine for tumor-directed therapy. Following 2 doses of lomustine with a dose reduction for severe neutropenia and 3 doses of bevacizumab, her brain MRI showed a second recurrence in the most recent operative bed (Figure 1K & L). Lomustine was discontinued after 2 cycles for severe neutropenia. Despite her history of hypertension, bevacizumab therapy did not require any interruptions for hypertension. Following 1 additional dose of bevacizumab, her brain MRI revealed further progressive disease (Figure 1M & N).

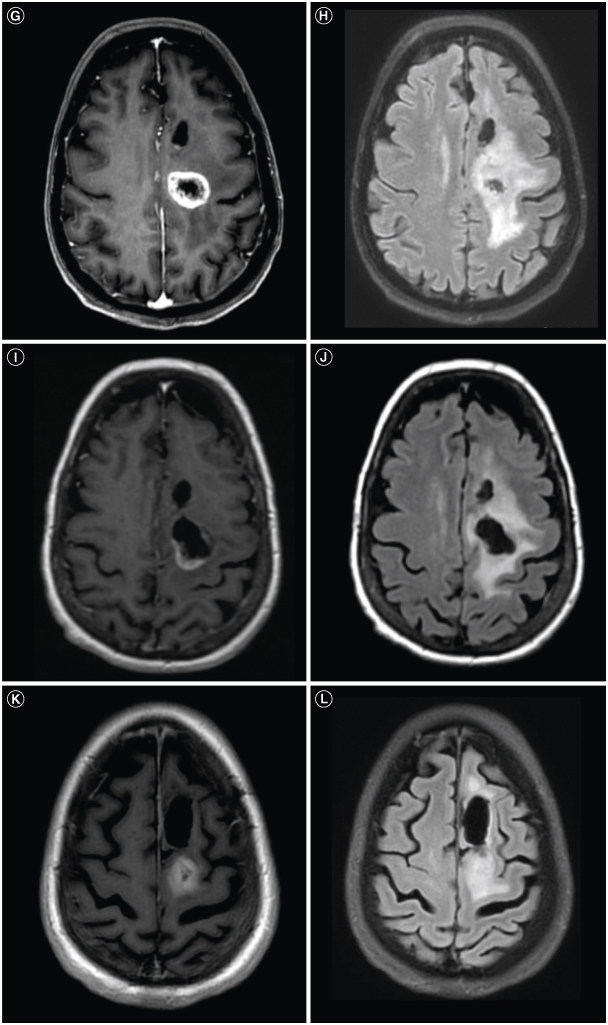

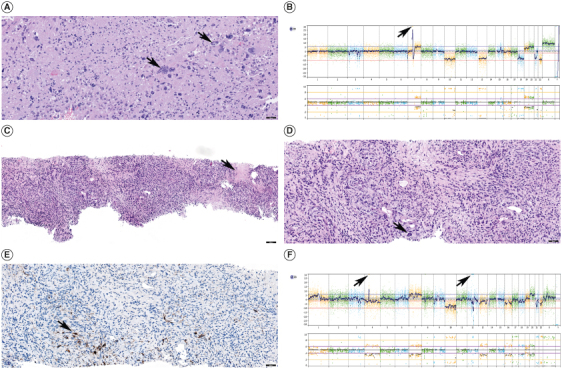

Figure 2.

Patient's residual/recurrent glioblastoma patholog. (A) Histologic section of the residual/recurrent glioblastoma with giant cell features (black arrows), Hematoxylin and Eosin, scale bar 50 microns. (B) Whole genome copy number profile of residual/recurrent glioblastoma showing gains of chromosomes 7, 19 and 20, losses of chromosomes 10, 13, 18, 21 and 22 and amplification of EGFR on chromosome 7 (black arrow). (C) Histologic section of the lung mass demonstrating predominantly spindle cell neoplasm with areas of necrosis (black arrow) morphologically consistent with residual/recurrent glioblastoma with sarcomatous features. Hematoxylin and Eosin, scale bar 100 microns. (D) Histologic section of the lung mass demonstrating predominantly spindle cell neoplasm consistent with residual/recurrent glioblastoma with sarcomatous features, scattered multinucleated giant cells (black arrow) are present similar to the patient's intracranial tumor. Hematoxylin and Eosin, scale bar 50 microns. (E) Immunohistochemical stain for GFAP performed on lung mass showed scattered positive cells (black arrow), confirming the glial nature of the neoplasm. Scale bar 50 microns. (F) Whole genome copy number profile of lung mass showing gains of chromosomes 1p, 7 and 20, losses of chromosomes 4, 10, 13, 16, 18, 21 and 22 and amplifications of PDGFRA and CDK4 on chromosomes 4 and 12, respectively (black arrows).

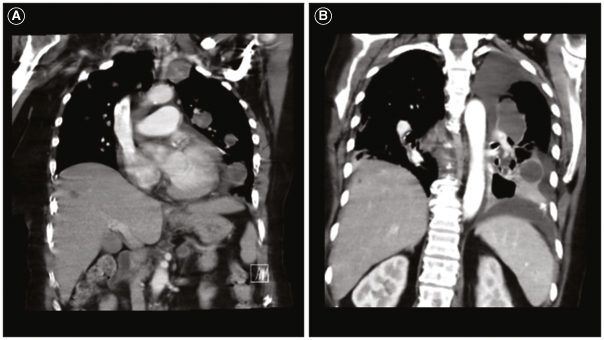

She subsequently developed a persistent cough. CT chest obtained to evaluate for pulmonary fibrosis instead showed multiple enhancing pulmonary masses (Figure 3A). CT imaging of her abdomen and pelvis and complete spine MRI showed no evidence of disease. Histopathologic analyses from her lung biopsy showed metastatic glioblastoma with sarcomatoid features (Figure 2C–E). Next-generation sequencing analysis demonstrated mutations in TP53 (p.R248W), TERT promoter (c.-124T>C) PTEN (p.M199del) amplifications of PDGFRA and CDK4, focal deep deletion of NAV3 and +7/-10 (Figure 2F). Salvage therapeutic options were restricted to oral therapies due to transportation limitations at her rehabilitation facility. She decided to proceed with lenvatinib.

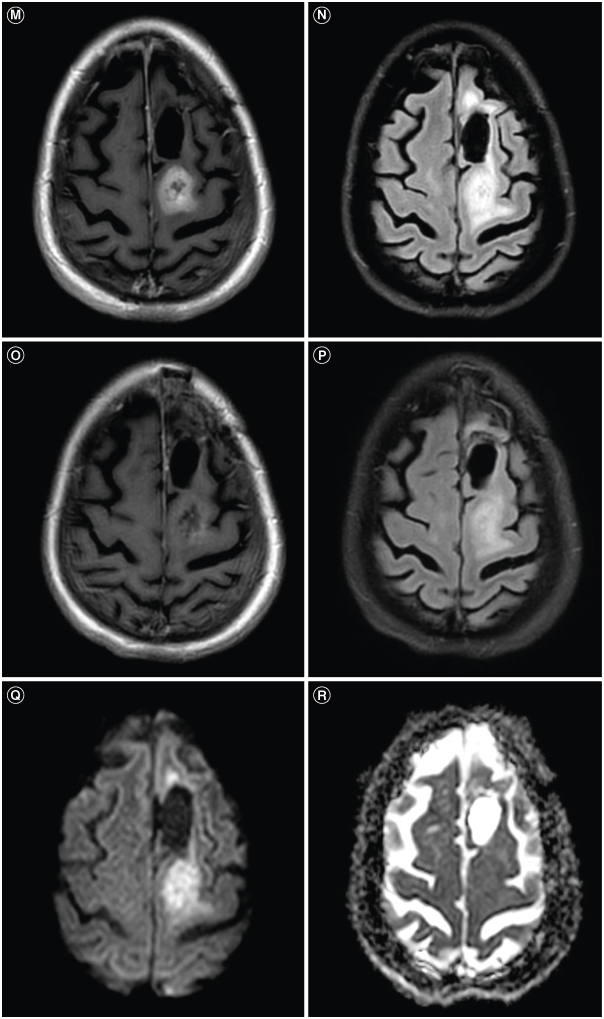

Figure 3.

Patient's metastatic glioblastoma to the lungs. (A) Coronal computed tomography (CT) chest shows multiple enhancing pulmonary metastases. (B) Coronal CT chest shows further progression of pulmonary metastases and new hepatic metastases.

Ten days later, repeat systemic imaging showed worsening pulmonary metastases and new hepatic lesions (Figure 3B). However, repeat brain MRI showed significant improvement in the enhancing tumor and T2 FLAIR hyperintensity (Figure 1O & P). Her care was transitioned to hospice and she unfortunately passed away 1.5 months after her metastatic glioblastoma diagnosis. Our patient's disease course is summarized in Figure 4. Ethical guidelines set out by the Declaration of Helsinki were followed in the preparation of this report and the patient provided written consent.

Figure 4.

Patient disease course (timeline in months).

3. Discussion

Metastatic glioblastoma is a rare disease with an especially poor prognosis [2–5,19,56]. The time from metastasis to death in our patient was 1.5 months, which corroborates with the median time from metastasis to death of 1.5 months in a study conducted by Lun et al. [19]. In the aforementioned study, analyses from 88 metastatic glioblastoma cases showed a median overall survival of 10.5 months and a median time from the initial diagnosis to extra-neural metastases of 8.5 months [19]. Our patient's findings substantiate these findings with an overall survival of 10 months and a time from the initial diagnosis to extra-neural metastases of 8.5 months. Despite her shortened overall survival which should preclude tumor cells from distal spread [10–12], she developed metastatic disease. Accordingly, we assessed for additional contributory risk factors that may have pre-determined her disease course. First, prior neurosurgical intervention is a described risk factor for the development of metastatic glioblastoma [57]. Our patient underwent two craniotomies with anatomic barrier compromise. However, there was no radiographic evidence of lateral ventricular violation or drop metastases with spinal dissemination. The postsurgical iatrogenic spread was unlikely to explain her metastases. Further, extra-neural metastases have been reported even in the absence of craniotomy and therefore does not account for her metastatic spread in its entirety [58–60]. Second, tumor recurrence has been reported to increase the risk for metastases, which may have contributed to her metastases. Following her initial diagnosis, early progression was noted on her postradiation brain MRI. Despite standard-of-care chemoradiation, she developed a second recurrence 4 months after her initial diagnosis, followed by a rapid third recurrence in her brain and lungs 4.5 months later. Taken together, these findings suggest that her tumor had an exceptionally aggressive biology. Though the pathogenesis for metastatic glioblastoma is poorly understood, we posit that the aggressive molecular characteristics of her tumor coupled with her immunocompromised state increased her risk for the eventual rise of metastatic disease.

Our patient's aggressive tumor biology is supported by an unmethylated MGMT status, which portends a poorer prognosis compared with methylated MGMT glioblastomas [61]. However, given that the vast majority of unmethylated MGMT glioblastomas do not spread distally, further investigation into the pathology from her lung biopsy was warranted. The pathology revealed sarcomatous histology, which is a recognized risk factor for disease dissemination in glioblastomas [15,39,62–67]. This new histologic finding was not present in her original or recurrent intracranial tumors. Limited investigations evaluating genetic alterations in metastatic glioblastoma show that TP53, TERT, PTEN and RB1 mutations are frequent alterations in metastatic glioblastoma [22,48]. Gain of chromosome 7 with loss of chromosome 10 has also been reported in metastatic glioblastoma [68,69]. Our patient's metastatic tumor carried alterations in TP53, TERT, PTEN and +7/-10, which were retained among her initial intracranial, recurrent intracranial and metastatic lung tumors (Figure 3). While our patient's intracranial glioblastoma and metastatic glioblastoma to the lung samples all harbored TP53, TERT promoter and PTEN mutations and +7/-10, these are some of the most frequent alterations in glioblastoma in adults and are not specific to metastatic tumors, or any particular histologic subtype [48].

We reason that our patient's immunocompromised state secondary to steroid dependence contributed to the development of her metastases. It is plausible that prior to the initiation of steroids, low-level latent circulating glioblastoma cells in her systemic circulation bearing no clinical consequence were controlled by her immune system. Following chronic steroid administration, dysregulated immune surveillance and immunosuppression set these previously quiescent circulating glioblastoma cells into motion with ultimate clinical relevance presenting as respiratory distress. This is substantiated by evidence garnered from organ donor-derived glioblastoma in transplant recipients on chronic immunosuppression to prevent organ rejection [9,70,71].

Routes of dissemination have been described for metastatic glioblastoma, including direct dissemination, hematogenous spread and lymphatic meningeal spread, [3,9,19]. Hematogenous spread was the most likely route of dissemination for metastases to her lungs on several bases. First, the lung is the most common site for glioblastoma dissemination [18]. Second, glioblastoma is an infiltrative tumor that can breach the blood–brain barrier, which may allow for vascular permeation of tumor cells. Third, the lungs are the first organ to receive deoxygenated blood from the brain following the heart. Based on the sequence of vascular flow from the brain to the heart and then systemic circulation, we propose the following: the tumor cells intravasated into the intracranial veins, proceeded onward to the heart, passed through the large pulmonary artery and into the tiny pulmonary capillaries where the tumor cells likely became entrapped, extravasated out and deposited into the lungs. Direct dissemination through the cerebral spinal fluid was unlikely given that evaluation of her complete spine with MRI showed no evidence of metastatic disease.

Treatment for metastatic glioblastoma is challenging and no standard treatment exists [11,72,73]. Therapeutic options gleaned from existing literature includes bevacizumab, surgery, temozolomide rechallenge, etoposide, irinotecan, procarbazine and immunotherapy [12,72,74,75]. Despite bevacizumab and lomustine, our patient developed metastatic glioblastoma to the lungs. In a similar case of metastatic glioblastoma to the lungs, Yang et al. reported a prolonged response of 27 months with combined bevacizumab and pembrolizumab [72]. The addition of pembrolizumab to bevacizumab was considered for our patient, but transport barriers from her rehabilitation facility restricted any intravenous therapy. Based on this limitation and her lack of response to bevacizumab, lenvatinib monotherapy, an oral multi-targeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor currently under investigation for glioblastoma [76–79], was initiated. A dramatic response was observed in her intracranial tumor on her follow-up post-contrast brain MRI (Figure 1O & P). For this imaging finding, we considered pseudo-response, a widely accepted imaging alteration associated with decreased vascular permeability from antiangiogenic therapy to explain this radiographic finding [80,81]. Lenvatinib has antiangiogenic, immunomodulatory and antitumor-inhibitory effects on multiple tyrosine kinase inhibitors [82,83]. However, our patient was also treated with 4 cycles of bevacizumab, a pure VEGF inhibitor [81], prior to lenvatinib with no apparent pseudo-response (Figure 1K–N).

Interestingly, her systemic lung disease did not demonstrate a response to lenvatinib. We speculate that her systemic glioblastoma originated from a subset of glioblastoma cells that were more aggressive than her intracranial glioblastoma. The vast differences in the histologic and molecular features of her intracranial glioblastoma compared to her sarcomatous lung glioblastoma corroborate these findings (Figure 2).

Limitations of the study include the nature of a single case report. In addition, this study is limited by short-term follow-up due to her transition to hospice. Firm conclusions cannot be drawn about the efficacy of lenvatinib given the shortened follow-up. As standard practice, we did not assess for metastatic disease at the time of initial glioblastoma diagnosis nor prior to her respiratory symptom development. It remains unknown if asymptomatic metastatic disease developed earlier in her disease course. Furthermore, we did not assess for tumor-circulating cells.

Future investigations should be directed at evaluating the potential role of genomic alterations to inform of potential metastatic risk in glioblastoma patients. Larger cohorts and longer follow-ups investigating the use of lenvatinib may impact treatment for metastatic glioblastoma. Lastly, new symptoms in a glioblastoma patient necessitate further diagnostic evaluation as early identification of metastases can expedite treatment and may improve overall survival.

4. Conclusion

Though rare, extra-neural metastases should be considered in the differential of a glioblastoma patient with new systemic symptoms. Early evidence gleaned from metastatic glioblastoma case studies suggests that genomic alterations may play a role in predicting risk for metastatic glioblastoma. Treatment options are needed for metastatic glioblastoma and novel therapies should be investigated.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the family (sister, brother, sister-in-law, niece and nephews) of our patient for their devoted support in the care of this patient.

Author contributions

CA Yuen – study concept, data collection, analysis, interpretation, manuscript drafting, revision and final approval. M Pekmezci – data collection, analysis, interpretation, manuscript drafting, revision and final approval. S Bao – data collection and final approval. X-T Kong – manuscript revision and final approval.

Financial disclosure

The authors have no financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Competing interests disclosure

Xiao-Tang Kong, MD received honorarium from Zai Lab for invited speeches for symposiums prior to July of 2021. The authors have no other competing interests or relevant affiliations with any organization or entity with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Writing disclosure

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Ethical conduct of research

The authors state that they have obtained appropriate institutional review board approval or have followed the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki for all human or animal experimental investigations. In addition, for investigations involving human subjects, informed consent has been obtained from the participants involved.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Need for ethics approval was needed.

Consent for publication

Written consent was obtained.

Data availability statement

The datasets from this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as: • of interest; •• of considerable interest

- 1.Ostrom QT, Price M, Neff C, et al. CBTRUS Statistical Report: Primary Brain and Other Central Nervous System Tumors Diagnosed in the United States in 2015–2019. Neuro Oncol. 2022;24(Suppl. 5):v1–v95. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noac202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu J, Shen L, Tang G, et al. Multiple extracranial metastases from glioblastoma multiforme: a case report and literature review. J Int Med Res. 2020;48(6):300060520930459. doi: 10.1177/0300060520930459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carvalho J, Barbosa CCL, Feher O, et al. Systemic dissemination of glioblastoma: literature review. Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992). 2019;65(3):460–468. doi: 10.1590/1806-9282.65.3.460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robert M, Wastie M. Glioblastoma multiforme: a rare manifestation of extensive liver and bone metastases. Biomed Imaging Interv J. 2008;4(1):e3. doi: 10.2349/biij.4.1.e3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beauchesne P. Extra-neural metastases of malignant gliomas: myth or reality? Cancers (Basel). 2011;3(1):461–477. doi: 10.3390/cancers3010461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Erlich SS, Davis RL. Spinal subarachnoid metastasis from primary intracranial glioblastoma multiforme. Cancer. 1978;42(6):2854–2864. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197812)42:6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anghileri E, Castiglione M, Nunziata R, et al. Extraneural metastases in glioblastoma patients: two cases with YKL-40-positive glioblastomas and a meta-analysis of the literature. Neurosurg Rev. 2016;39(1):37–45; discussion 45–36. doi: 10.1007/s10143-015-0656-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pietschmann S, Von Bueren AO, Kerber MJ, Baumert BG, Kortmann RD, Muller K. An individual patient data meta-analysis on characteristics, treatments and outcomes of glioblastoma/gliosarcoma patients with metastases outside of the central nervous system. PLOS ONE. 2015;10(4):e0121592. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muller C, Holtschmidt J, Auer M, et al. Hematogenous dissemination of glioblastoma multiforme. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(247):247ra101. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3009095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sullivan JP, Nahed BV, Madden MW, et al. Brain tumor cells in circulation are enriched for mesenchymal gene expression. Cancer Discov. 2014;4(11):1299–1309. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-0471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chai M, Shi Q. Extracranial metastasis of glioblastoma with genomic analysis: a case report and review of the literature. Transl Cancer Res. 2022;11(8):2917–2925. doi: 10.21037/tcr-22-955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yasuhara T, Tamiya T, Meguro T, et al. Glioblastoma with metastasis to the spleen – case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2003;43(9):452–456. doi: 10.2176/nmc.43.452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fidler IJ. The pathogenesis of cancer metastasis: the “seed and soil” hypothesis revisited. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3(6):453–458. doi: 10.1038/nrc1098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nduom EK, Yang C, Merrill MJ, Zhuang Z, Lonser RR. Characterization of the blood–brain barrier of metastatic and primary malignant neoplasms. J Neurosurg. 2013;119(2):427–433. doi: 10.3171/2013.3.JNS122226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kurdi M, Baeesa S, Okal F, et al. Extracranial metastasis of brain glioblastoma outside CNS: pathogenesis revisited. Cancer Rep (Hoboken). 2023;6(12):e1905. doi: 10.1002/cnr2.1905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Describes the possible pathogenesis of extra-neural glioblastoma.

- 16.Fonkem E, Lun M, Wong ET. Rare phenomenon of extracranial metastasis of glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(34):4594–4595. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.0187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goodwin CR, Liang L, Abu-Bonsrah N, et al. Extraneural glioblastoma multiforme vertebral metastasis. World Neurosurg. 2016;89:578–582; e573. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2015.11.061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Piccirilli M, Brunetto GM, Rocchi G, Giangaspero F, Salvati M. Extra central nervous system metastases from cerebral glioblastoma multiforme in elderly patients. Clinico-pathological remarks on our series of seven cases and critical review of the literature. Tumori. 2008;94(1):40–51. doi: 10.1177/030089160809400109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lun M, Lok E, Gautam S, Wu E, Wong ET. The natural history of extracranial metastasis from glioblastoma multiforme. J Neurooncol. 2011;105(2):261–273. doi: 10.1007/s11060-011-0575-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Describes the biology of extra-neural glioblastoma.

- 20.Mirzayan MJ, Samii M, Petrich T, Borner AR, Knapp WH, Samii A. Detection of multiple extracranial metastases from glioblastoma multiforme by means of whole-body [18F]FDG-PET. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2005;32(7):853. doi: 10.1007/s00259-004-1749-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Onda K, Tanaka R, Takahashi H, Takeda N, Ikuta F. Cerebral glioblastoma with cerebrospinal fluid dissemination: a clinicopathological study of 14 cases examined by complete autopsy. Neurosurgery. 1989;25(4):533–540. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198910000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Noch EK, Sait SF, Farooq S, Trippett TM, Miller AM. A case series of extraneural metastatic glioblastoma at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. Neurooncol Pract. 2021;8(3):325–336. doi: 10.1093/nop/npaa083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hersh AM, Lubelski D, Theodore N. Management of glioblastoma metastatic to the vertebral spine. World Neurosurg. 2022;161:52–53. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2022.01.074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sickler R 3rd, Bhattacharjee M, Tandon N, Zhu J, Stark J. Metastatic glioblastoma multiforme to the vertebral column. JCO Oncol Pract. 2021;17(2):113–115. doi: 10.1200/OP.20.00347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lawton CD, Nagasawa DT, Yang I, Fessler RG, Smith ZA. Leptomeningeal spinal metastases from glioblastoma multiforme: treatment and management of an uncommon manifestation of disease. J Neurosurg Spine. 2012;17(5):438–448. doi: 10.3171/2012.7.SPINE12212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Potter CR, Kaufman R, Page RB, Chung C. Glioblastoma multiforme metastatic to the neck. Am J Otolaryngol. 1983;4(1):74–76. doi: 10.1016/S0196-0709(83)80007-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wallace CJ, Forsyth PA, Edwards DR. Lymph node metastases from glioblastoma multiforme. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1996;17(10):1929–1931. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beauchesne P, Soler C, Mosnier JF. Diffuse vertebral body metastasis from a glioblastoma multiforme: a technetium-99m Sestamibi single-photon emission computerized tomography study. J Neurosurg. 2000;93(5):887–890. doi: 10.3171/jns.2000.93.5.0887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hubner F, Braun V, Richter HP. Case reports of symptomatic metastases in four patients with primary intracranial gliomas. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2001;143(1):25–29. doi: 10.1007/s007010170134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Allan RS. Scalp metastasis from glioblastoma. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75(4):559. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ogungbo BI, Perry RH, Bozzino J, Mahadeva D. Report of GBM metastasis to the parotid gland. J Neurooncol. 2005;74(3):337–338. doi: 10.1007/s11060-005-1480-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taha M, Ahmad A, Wharton S, Jellinek D. Extra-cranial metastasis of glioblastoma multiforme presenting as acute parotitis. Br J Neurosurg. 2005;19(4):348–351. doi: 10.1080/02688690500305506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Templeton A, Hofer S, Topfer M, et al. Extraneural spread of glioblastoma – report of two cases. Onkologie. 2008;31(4):192–194. doi: 10.1159/000118627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhen L, Yufeng C, Zhenyu S, Lei X. Multiple extracranial metastases from secondary glioblastoma multiforme: a case report and review of the literature. J Neurooncol. 2010;97(3):451–457. doi: 10.1007/s11060-009-0044-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Armstrong TS, Prabhu S, Aldape K, et al. A case of soft tissue metastasis from glioblastoma and review of the literature. J Neurooncol. 2011;103(1):167–172. doi: 10.1007/s11060-010-0370-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kalokhe G, Grimm SA, Chandler JP, Helenowski I, Rademaker A, Raizer JJ. Metastatic glioblastoma: case presentations and a review of the literature. J Neurooncol. 2012;107(1):21–27. doi: 10.1007/s11060-011-0731-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seo YJ, Cho WH, Kang DW, Cha SH. Extraneural metastasis of glioblastoma multiforme presenting as an unusual neck mass. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2012;51(3):147–150. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2012.51.3.147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blume C, Von Lehe M, Van Landeghem F, Greschus S, Bostrom J. Extracranial glioblastoma with synchronous metastases in the lung, pulmonary lymph nodes, vertebrae, cervical muscles and epidural space in a young patient – case report and review of literature. BMC Res Notes. 2013;6:290. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-6-290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dawar R, Fabiano AJ, Qiu J, Khushalani NI. Secondary gliosarcoma with extra-cranial metastases: a report and review of the literature. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2013;115(4):375–380. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2012.06.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lettau M, Jedrusik P, Laible M. Dural metastases of a glioblastoma. Clin Neuroradiol. 2013;23(4):323–325. doi: 10.1007/s00062-012-0192-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Romero-Rojas AE, Diaz-Perez JA, Amaro D, Lozano-Castillo A, Chinchilla-Olaya SI. Glioblastoma metastasis to parotid gland and neck lymph nodes: fine-needle aspiration cytology with histopathologic correlation. Head Neck Pathol. 2013;7(4):409–415. doi: 10.1007/s12105-013-0448-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Undabeitia J, Castle M, Arrazola M, Pendleton C, Ruiz I, Urculo E. Multiple extraneural metastasis of glioblastoma multiforme. An Sist Sanit Navar. 2015;38(1):157–161. doi: 10.4321/S1137-66272015000100022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Franceschi S, Lessi F, Aretini P, et al. Molecular portrait of a rare case of metastatic glioblastoma: somatic and germline mutations using whole-exome sequencing. Neuro Oncol. 2016;18(2):298–300. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nov314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lewis GD, Rivera AL, Tremont-Lukats IW, Ballester-Fuentes LY, Zhang YJ, Teh BS. GBM skin metastasis: a case report and review of the literature. CNS Oncol. 2017;6(3):203–209. doi: 10.2217/cns-2016-0042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Simonetti G, Silvani A, Fariselli L, et al. Extra central nervous system metastases from glioblastoma: a new possible trigger event? Neurol Sci. 2017;38(10):1873–1875. doi: 10.1007/s10072-017-3036-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hori YS, Fukuhara T, Aoi M, Oda K, Shinno Y. Extracranial glioblastoma diagnosed by examination of pleural effusion using the cell block technique: case report. Neurosurg Focus. 2018;44(6):E8. doi: 10.3171/2017.8.FOCUS17403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Janik K, Och W, Popeda M, et al. Glioblastoma with BRAFV600E mutation and numerous metastatic foci: a case report. Folia Neuropathol. 2019;57(1):72–79. doi: 10.5114/fn.2019.83833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tamai S, Kinoshita M, Sabit H, et al. Case of metastatic glioblastoma with primitive neuronal component to the lung. Neuropathology. 2019;39(3):218–223. doi: 10.1111/neup.12553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Describes histological features of metastatic glioblastoma.

- 49.Houston SC, Crocker IR, Brat DJ, Olson JJ. Extraneural metastatic glioblastoma after interstitial brachytherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;48(3):831–836. doi: 10.1016/S0360-3016(00)00662-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hsu BH, Lee WH, Yang ST, Han CT, Tseng YY. Spinal metastasis of glioblastoma multiforme before gliosarcomatous transformation: a case report. BMC Neurol. 2020;20(1):178. doi: 10.1186/s12883-020-01768-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rossi J, Giaccherini L, Cavallieri F, et al. Extracranial metastases in secondary glioblastoma multiforme: a case report. BMC Neurol. 2020;20(1):382. doi: 10.1186/s12883-020-01959-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Umphlett M, Shea S, Tome-Garcia J, et al. Widely metastatic glioblastoma with BRCA1 and ARID1A mutations: a case report. BMC Cancer. 2020;20(1):47. doi: 10.1186/s12885-020-6540-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Al-Sardi M, Alfayez A, Alwelaie Y, Al-Twairqi A, Hamadi F, Alokla K. A rare case of metastatic glioblastoma diagnosed by endobronchial ultrasound-transbronchial needle aspiration. Case Rep Pulmonol. 2022;2022:5453420. doi: 10.1155/2022/5453420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kumaria A, Teale A, Kulkarni GV, Ingale HA, Macarthur DC, Robertson IJA. Glioblastoma multiforme metastatic to lung in the absence of intracranial recurrence: case report. Br J Neurosurg. 2022;36(2):290–292. doi: 10.1080/02688697.2018.1529296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nakib CE, Hajjar R, Zerdan MB, et al. Glioblastoma multiforme metastasizing to the skin, a case report and literature review. Radiol Case Rep. 2022;17(1):171–175. doi: 10.1016/j.radcr.2021.10.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cunha M, Maldaun MVC. Metastasis from glioblastoma multiforme: a meta-analysis. Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992). 2019;65(3):424–433. doi: 10.1590/1806-9282.65.3.424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• This publication is a meta-analysis of glioblastoma metastases.

- 57.Hamilton JD, Rapp M, Schneiderhan T, et al. Glioblastoma multiforme metastasis outside the CNS: three case reports and possible mechanisms of escape. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(22):e80–e84. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.48.7546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Anzil AP. Glioblastoma multiforme with extracranial metastases in the absence of previous craniotomy. Case Rep J Neurosurg. 1970;33(1):88–94. doi: 10.3171/jns.1970.33.1.0088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Describes the phenomenon of extra-cranial glioblastoma without neurosurgical intervention, one of the potential risk factors for glioblastoma dissemination.

- 59.Hulbanni S, Goodman PA. Glioblastoma multiforme with extraneural metastases in the absence of previous surgery. Cancer. 1976;37(3):1577–1583. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197603)37:3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Describes the phenomenon of extra-cranial glioblastoma without neurosurgical intervention, one of the potential risk factors for glioblastoma dissemination.

- 60.Brew BJ, Garrick R. Gliomas presenting outside the central nervous system. Clin Exp Neurol. 1987;23:111–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hegi ME, Diserens AC, Gorlia T, et al. MGMT gene silencing and benefit from temozolomide in glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(10):997–1003. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Huang P, Allam A, Taghian A, Freeman J, Duffy M, Suit HD. Growth and metastatic behavior of five human glioblastomas compared with nine other histological types of human tumor xenografts in SCID mice. J Neurosurg. 1995;83(2):308–315. doi: 10.3171/jns.1995.83.2.0308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Morantz RA, Feigin I, Ransohoff J 3rd. Clinical and pathological study of 24 cases of gliosarcoma. J Neurosurg. 1976;45(4):398–408. doi: 10.3171/jns.1976.45.4.0398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Friker LL, Tzaridis T, Enkirch SJ, et al. Gliosarcoma with extensive extracranial metastatic spread and familial coincidence: a case report. Pathol Res Pract. 2023;244:154399. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2023.154399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Describes the risk factor of glioblastoma metastases with the risk factor of gliosarcoma.

- 65.Perry JR, Laperriere N, O'Callaghan CJ, et al. Short-course radiation plus temozolomide in elderly patients with glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(11):1027–1037. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1611977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wick W, Platten M, Meisner C, et al. Temozolomide chemotherapy alone versus radiotherapy alone for malignant astrocytoma in the elderly: the NOA-08 randomised, Phase III trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(7):707–715. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70164-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Reis RM, Konu-Lebleblicioglu D, Lopes JM, Kleihues P, Ohgaki H. Genetic profile of gliosarcomas. Am J Pathol. 2000;156(2):425–432. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64746-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Marinari E, Dutoit V, Nikolaev S, et al. Clonal evolution of a high-grade pediatric glioma with distant metastatic spread. Neurol Genet. 2021;7(2):e561. doi: 10.1212/NXG.0000000000000561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Georgescu MM, Olar A. Genetic and histologic spatiotemporal evolution of recurrent, multifocal, multicentric and metastatic glioblastoma. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2020;8(1):10. doi: 10.1186/s40478-020-0889-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schonsteiner SS, Bommer M, Haenle MM, et al. Rare phenomenon: liver metastases from glioblastoma multiforme. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(23):e668–e671. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.9232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jimsheleishvili S, Alshareef AT, Papadimitriou K, et al. Extracranial glioblastoma in transplant recipients. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2014;140(5):801–807. doi: 10.1007/s00432-014-1625-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Describes the immunocompromised state as a possible risk factor for glioblastoma metastases.

- 72.Yang G, Fang Y, Zhou M, et al. Case report: the effective response to pembrolizumab in combination with bevacizumab in the treatment of a recurrent glioblastoma with multiple extracranial metastases. Front Oncol. 2022;12:948933. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.948933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pietschmann S, Von Bueren AO, Henke G, Kerber MJ, Kortmann RD, Muller K. An individual patient data meta-analysis on characteristics, treatments and outcomes of the glioblastoma/gliosarcoma patients with central nervous system metastases reported in literature until 2013. J Neurooncol. 2014;120(3):451–457. doi: 10.1007/s11060-014-1596-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Liu H, Chen C, Li F, et al. Glioblastoma multiforme with vertebral metastases: a case report. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2022;28(2):310–313. doi: 10.1111/cns.13785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Engelhard HH, Willis AJ, Hussain SI, et al. Etoposide-bound magnetic nanoparticles designed for remote targeting of cancer cells disseminated within cerebrospinal fluid pathways. Front Neurol. 2020;11:596632. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.596632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Perez-Fidalgo JA, Martinelli E. Lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab a new effective combination of targeted agents. ESMO Open. 2023;8(2):101157. doi: 10.1016/j.esmoop.2023.101157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Szklener K, Mazurek M, Wieteska M, Waclawska M, Bilski M, Mandziuk S. New directions in the therapy of glioblastoma. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(21):5377. doi: 10.3390/cancers14215377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Li J, Zou CL, Zhang ZM, Lv LJ, Qiao HB, Chen XJ. A multi-targeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor lenvatinib for the treatment of mice with advanced glioblastoma. Mol Med Rep. 2017;16(5):7105–7111. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2017.7456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Arai N, Sasaki H, Tamura R, Ohara K, Yoshida K. Unusual magnetic resonance imaging findings of a glioblastoma arising during treatment with lenvatinib for thyroid cancer. World Neurosurg. 2017;107:1047.e1049–1047.e1015. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2017.08.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wen PY, Cloughesy TF, Ellingson BM, et al. Report of the jumpstarting brain tumor drug development coalition and FDA clinical trials neuroimaging endpoint workshop (January 30, 2014, Bethesda MD). Neuro Oncol. 2014;16(Suppl. 7):vii36–vii47. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nou226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chinot OL, De La Motte Rouge T, Moore N, et al. AVAglio: Phase III trial of bevacizumab plus temozolomide and radiotherapy in newly diagnosed glioblastoma multiforme. Adv Ther. 2011;28(4):334–340. doi: 10.1007/s12325-011-0007-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Motzer RJ, Taylor MH, Evans TRJ, et al. Lenvatinib dose, efficacy, and safety in the treatment of multiple malignancies. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2022;22(4):383–400. doi: 10.1080/14737140.2022.2039123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Casadei-Gardini A, Rimini M, Tada T, et al. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab versus lenvatinib for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a large real-life worldwide population. Eur J Cancer. 2023;180:9–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2022.11.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets from this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.