Doctors deal with complementary medicine in a variety of professional situations. Patients may ask for advice about whether to pursue complementary therapies or which therapist to consult; they may request referral or delegation, either privately or on the NHS; or they may want to discuss treatment or advice given by complementary practitioners. Doctors prescribing drugs to patients taking complementary treatments may have concerns about possible interactions. Doctors should therefore consider strategies for minimising risk and facilitating sensible and appropriate discussions with patients and complementary practitioners.

Medical attitudes

Surveys of doctors' attitudes to complementary medicine show that, overall, physicians believe it is moderately effective, but low response rates make some studies unreliable. Although hospital doctors and older general practitioners tend to be more sceptical than younger doctors and medical students, most respondents believe that some of the more established forms are of benefit and should be available on the NHS. Younger doctors and medical students are more likely to perceive their knowledge of complementary medicine as inadequate and to want more tuition in the subject.

Common concerns of doctors about complementary medicine

Patients may see unqualified complementary practitioners

Patients may risk missed or delayed diagnosis

Patients may stop or refuse effective conventional treatment

Patients may waste money on ineffective treatments

Patients may experience dangerous adverse effects from treatment

The mechanism of some complementary treatments is so implausible they cannot possibly work

Qualitative research shows that many doctors want to be supportive of patients' choices and would welcome further information, although they generally regard complementary therapies as scientifically unproved. Doctors' concerns about such therapies include whether they are used as an adjunct or an alternative to conventional care, how effective conventional treatments are in the given condition, and the possibility of adverse effects.

Promoting good practice

Doctors can have an important role in identifying patients who use complementary medicine, minimising their risk of harm, and, as far as possible, ensuring that their choice of treatment is in their best interests. The key to achieving this in practice is often to maintain open, clear, and effective communication with patients, and sometimes complementary practitioners.

Consider asking about complementary medicine use when

Patient has chronic or relapsing disease

Conventional approaches require maintenance treatment

Patient is experiencing or is concerned about adverse drug reactions

Patient is unhappy about progress

There is unexplained poor compliance with treatment or follow up

Useful questions when inquiring about use of complementary medicine

Healthcare behaviour

Have you tried any other treatment approaches for this problem?

Have you ever seen a complementary or alternative practitioner for this problem?

Have you ever tried changing your diet because you thought it might help this problem?

Have you used any herbal or natural remedies that you have bought from a chemist or health food shop?

Healthcare attitudes

What are you hoping will come out of your complementary treatment?

What was it that encouraged you to try complementary medicine?

Communication and cooperation

Would you like to ask your complementary therapist to let me know about your treatment and progress?

Identifying complementary medicine users

There is evidence that most people who have used complementary medicine do not tell their doctors. Specific questions may be required to elicit use, as when inquiring about drugs and alcohol intake.

Minimising potential risks

As discussed in earlier articles, there are potential risks associated with the use of complementary medicine. Although these are likely to be rare, it is important that patients are adequately informed and take basic precautions to reduce their chances of harm.

Delayed or missed diagnosis

Many conventional professionals are concerned that, if complementary treatments are given to patients before a definite diagnosis has been made, serious pathology and opportunities for effective conventional treatment may be missed. This is a real concern; there are a few reports of fatalities occurring for this reason. However, evidence indicates that most patients with ongoing symptoms consult their general practitioners before trying complementary medicine.

Essentials of good practice in complementary medicine

The practitioner should practise only to the level to which he or she has achieved competence

The practitioner should take a sufficient medical history to ensure there are no contraindications to the intended treatment

The practitioner should not advise any changes to conventional treatment without seeking the advice of a doctor

The practitioner should ideally communicate with the patient's general practitioner, including the following information: complementary medicine diagnosis, all treatment and advice given, likely duration of treatment, date of discharge or any follow up plans

There should an agreed time frame in which progress should be assessed

In addition, practitioner members of the main complementary medicine regulatory bodies are usually trained to recognise “red flag” symptoms and redirect patients to conventional care. For example, there are reports of chiropractors and osteopaths diagnosing spinal malignancies and referring appropriately. Problems are less likely if patients are using complementary medicine alongside conventional care. Doctors and complementary practitioners both have a role in ensuring that patients seek medical assessment and follow up before, during, and after complementary treatment for persisting problems.

Stopping or refusing conventional care

There are reports of serious adverse consequences of complementary practitioners giving advice which contradicts that of a doctor. Most of these occur because patients suddenly stop beneficial maintenance medication such as asthma or anticonvulsant treatment. Immunisations, antibiotics, and diet are other areas where the influence of complementary medicine can cause particular difficulties. Again, good communication between all parties is the most effective protection, and patients should be made aware of the risks of sudden changes. Patients taking long term medication should be encouraged to find a complementary practitioner who is happy to liaise and cooperate with their general practitioner.

Interaction between complementary and conventional treatments

Little information has been published on the combined use of complementary and conventional treatments, but some serious interactions have been reported. These have mostly involved herbal products or dietary supplements. The lack of a formal reporting system makes their true incidence unknown, and more reliable information is needed. Encouraging patients who are taking conventional medication to disclose and discuss intentions to use complementary therapies, and to initiate treatment only under medical supervision, may help to reduce risks.

Preventing fragmentation of care

Use of complementary medicine is not generally recorded in general practitioners' notes. A patient's health care may therefore become fragmented and uncoordinated. Again, good communication between complementary practitioners and general practitioners can greatly improve this situation.

Finding a reputable practitioner

Patients should be encouraged to follow a few simple rules when choosing a complementary practitioner (see box).

Finding a reputable complementary medicine practitioner

The practitioner should have current registration and follow the code of conduct laid out by the appropriate complementary medicine professional body

The practitioner should hold full insurance to practise in the relevant setting (employers or regular referrers should ask to see current insurance certificates)

In addition, references from a respected and impartial third party (such as a previous client, NHS employer, etc) may be sought

Knowing what to expect

Increased awareness of some of the general problems that can occur with complementary treatment and the specific adverse effects of the individual therapies (see earlier articles) can help patients make more informed choices.

Ensuring treatment is in the patient's best interests

Although most patients seek complementary medicine on quite reasonable grounds, there are cases when a patient's use of complementary treatments should be questioned.

Patient has unrealistic expectations

High expectations can be generated or encouraged by complementary practitioners and sensational media coverage. However, they are often a feature of a patient's unwillingness to accept a diagnosis of chronic or progressive disease.

Costs outweigh the benefits

Patients often seek complementary medicine for longstanding and difficult to manage problems. In order to maintain hope of improvement or cure they may continue to pay for treatment long after it has become clear that it is not of value. The lack of routine assessments or incentives for private practitioners to bring treatment to an end may exacerbate this situation. Patients may sometimes feel guilty about lack of progress and find it difficult to stop seeing a complementary practitioner. Most reputable practitioners assess progress regularly with their patients.

Taking patients seriously

Patients who are considering complementary medicine may have underlying motives that need exploration. Discussing these fully with a doctor may be therapeutic, and sometimes sufficient in itself. Patients may be experiencing unacceptable side effects from conventional treatment or have difficulty adjusting to their illness. While doctors cannot be expected to provide detailed advice about complementary treatments, they should be aware of their patients' health concerns and beliefs. A doctor who listens and supports patient choice, and whose advice minimises risk, rather than dismisses complementary medicine on principle is more likely to encourage patients to use it appropriately, as an adjunct rather than an alternative to conventional care.

Facilitating effective communication

This article has stressed the need for effective communication between doctors, patients and complementary practitioners. There are, however, often considerable barriers to such communication. These may result from philosophical and cultural differences, private versus NHS settings, and from underlying issues of power and control. Practitioners should be aware that they may not all speak the same healthcare “language” or be looking for the same type of patient response. Written referral and discharge letters, discussions about individual patients, and multidisciplinary meetings can be helpful strategies.

Dealing with interdisciplinary issues with complementary practitioners

Encourage patients to voice their concerns

Refrain from personally directed criticism of other practitioners

Offer your professional opinion neutrally

Offer patients a chance for a second opinion

If malpractice or abuse is suspected, obtain as much information as possible to support your position and seek advice from your defence society and from the relevant complementary medicine professional body

Which therapy and which practitioner?

Doctors are used to a one to one correspondence between particular diseases and particular treatments. Many complementary techniques, however, have broad and overlapping indications. For example, evidence shows that acupuncture can treat conditions as disparate as stroke, nausea, and chronic pain and that pain can respond to treatments as disparate as acupuncture, manipulation, and hypnosis.

Determining the most appropriate therapy for an individual patient is therefore generally a case of identifying those techniques for which there is the strongest evidence of benefit in the given condition and choosing the one that the patient finds most acceptable and believes is most likely to be of benefit. Finding the right practitioner—one who is appropriately qualified, with whom the patient and doctor can communicate and trust—is a prime consideration.

Learning about complementary medicine

It has been argued that doctors should learn about complementary medicine because it is widely used and because it may have substantial beneficial and harmful effects. Informal methods of education—such as reading books or journals, searching the internet, or via contact with practitioners or practitioner organisations—are not always objective or reliable. The BMA recommends establishing more formal “familiarisation” initiatives.

Sources of further information

General databases

Medline—Includes some published research on complementary medicine, including papers from some specialist complementary medicine journals

Cochrane Library—Includes most published controlled trials of complementary medicine

CISCOM database

Specialist database of published research

Held at Research Council for Complementary Medicine, 505 Riverbank House, 1 Putney Bridge Approach, London SW6 3JD. Tel: 020 7384 1772. Fax: 020 7384 1736. Email: info@rccm.org.uk

Complementary medicine registering bodies

Hold codes of conduct, details of insurance cover, and lists of contraindications for most therapies

See earlier articles for full lists and addresses

Information on safety issues

See earlier articles about individual therapies

Information on the internet

US National Institute of Health National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (formerly Office of Alternative Medicine). URL: http://nccam.nih.gov

Focus on Alternative and Complementary Medicine. URL: www.exeter.ac.uk/FACT

See earlier articles for details about individual therapies

Nearly half of all UK medical schools now offer limited teaching in complementary medicine, although standards vary and courses are usually an option for only a few students. Some postgraduate medical centres run courses of varying content and quality that are approved for postgraduate education allowance to provide a basic introduction to several complementary disciplines.

Some doctors undertake training to enable them to practise some form of complementary therapy. The basic choice is between courses that train non-medically qualified practitioners and those specifically designed for doctors. The former take considerably more time and involve a more detailed study of traditional techniques; the latter are shorter and often take a “medicalised” view of the complementary technique. Doctors may decide to learn a few simple techniques or to change their practice more fundamentally to specialise in a complementary discipline.

Further reading

Lewith G, Kenyon J, Lewis P. Complementary medicine: an integrated approach. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996. (Oxford General Practice Series)

Sharma U. Complementary medicine today: practitioners and patients. Rev ed. London: Routledge, 1995

Complementary medicine: new approaches to good practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993

Medical attitudes to complementary medicine: a resource pack. London: Research Council for Complementary Medicine, 1998

Figure.

Most patients do not tell their general practitioner if they are using complementary medicine. This may place some at unnecessary risk

Figure.

A Chinese herbal pharmacy. As many complementary medicines contain pharmacologically active agents it is important to establish what patients are using in order to minimise the risk of interactions with conventional drugs

Figure.

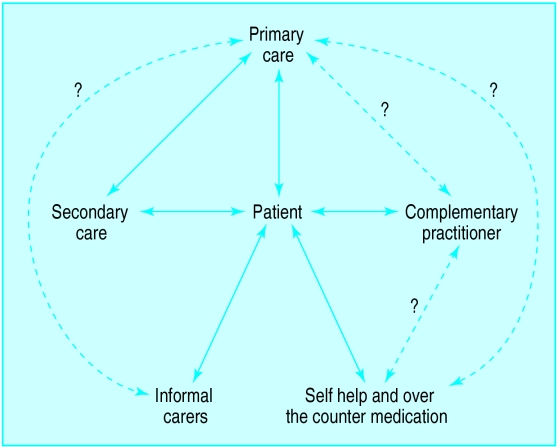

The patient is at the centre of a complicated web of healthcare activity and communication: the use of complementary medicine may increase the potential for fragmented care

Figure.

Reputable complementary practitioners should regularly assess progress with their patients

Figure.

Although doctors may claim to be unaware of published data on complementary medicine, results from many randomised controlled trials of complementary medicine have been published in major, peer reviewed journals

Acknowledgments

The picture of a general practice consultation is reproduced with permission of Antonia Reeve/Science Photo Library. The picture of a Chinese herbal pharmacy is reproduced with permission of Phil Schermeister/Corbis. The pictures of a chiropractic assessment and of medical journals are reproduced with permission of BMJ/Ulrike Preuss.

For their assistance with photographs used to illustrate this series, we thank Dr Carl D Irwin, chiropractic; Jill Hedison, osteopathy; David Charlaff, acupuncture; Roxanne Clark, massage; Carol Taylor, reflexology. We also thank Dr Sadeem Abutrab, Cassandra Marks, Helen Robertson, and Harrison Smith.

Footnotes

The ABC of complementary medicine is edited and written by Catherine Zollman and Andrew Vickers. Catherine Zollman is a general practitioner in Bristol, and Andrew Vickers will shortly take up a post at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York. At the time of writing, both worked for the Research Council for Complementary Medicine, London. The series will be published as a book in Spring 2000.