Abstract

Background: Distal junctional kyphosis (DJK) is a concerning complication for surgeons performing cervical deformity (CD) surgery. Patients sustaining such complications may demonstrate worse recovery profiles compared to their unaffected peers. Methods: DJK was defined as a >10° change in kyphosis between LIV and LIV-2, and a >10° index angle. CD patients were grouped according to the development of DJK by 3M vs. no DJK development. Means comparison tests and regression analyses used to analyze differences between groups and arelevant associations. Results: A total of 113 patients were included (17 DJK, 96 non-DJK). DJK patients were more sagittally malaligned preop, and underwent more osteotomies and combined approaches. Postop, DJK patients experienced more dysphagia (17.7% vs. 4.2%; p = 0.034). DJK patients remained more malaligned in cSVA through the 2-year follow-up. DJK patients exhibited worse patient-reported outcomes from 3M to 1Y, but these differences subsided when following patients through to 2Y; they also exhibited worse NDI (65.3 vs. 35.3) and EQ5D (0.68 vs. 0.79) scores at 1Y (both p < 0.05), but these differences had subsided by 2Y. Conclusions: Despite patients exhibiting similar preoperative health-related quality of life metrics, patients who developed early DJK exhibited worse postoperative neck disability following the development of their DJK. These differences subsided by the 2-year follow-up, highlighting the prolonged but eventually successful course of many DJK patients after CD surgery.

Keywords: cervical deformity, alignment, distal junctional kyphosis, recovery kinetics

1. Introduction

Adult cervical deformity (CD) is a complex pathology characterized by the interruption of the normal cervical vertebral alignment in the sagittal and/or coronal planes [1,2]. CD is of heterogenous etiology, with the potential to cause severe discomfort and disability, and is also associated with poor health-related quality of life metrics [3]. Surgical intervention for CD can provide affected patients with significant improvements in quality of life [4,5]. However, it is a complex surgery and is associated with considerable complication and revision rates [2,5].

Distal junctional kyphosis (DJK) is a mechanical failure complication which remains of particular concern following surgical correction for CD, and is a frequent reason for revision surgery [6,7]. DJK denotes a progression in the degree of kyphosis of the vertebral segment adjacent to the lower instrumented vertebra postoperatively [8]. DJK can result in considerable morbidity, including pain, imbalance, and degenerative disc pathology due to increased mechanical stress on adjacent vertebral segments [9,10]. The development of early DJK (within three months postoperatively) is associated with particularly more severe radiographic malalignment and neurologic decline [11]. To our knowledge, there is limited information on the effect of early postoperative DJK on CD surgical recovery.

Mechanical failure complications following surgery to the thoracolumbar spine, such as proximal junctional kyphosis and proximal junctional failure, have been well studied and a body of literature exists which provides strategy for preventing such complications and identifying particularly at-risk patients [12,13]. DJK, which is the more likely mechanical complication following CD surgery, has not been studied as extensively. In this context, this study aims to investigate the recovery course following CD surgery in patients who develop early DJK, particularly examining the variation in health-related quality of life metrics up to two years postoperatively.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

This was a retrospective cohort study of adult cervical deformity (CD) patients aged 18 years and older who were prospectively enrolled into a single-center registry between 2012 and 2019. Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was obtained prior to enrolment and all included individuals provided informed consent. CD was defined as ≥1 of the following: C2–C7 sagittal kyphosis > 15°; T1 slope–cervical lordosis mismatch (TS-CL) > 35°; C2–C7 sagittal vertical axis (cSVA) > 40 mm; chin-brow vertical angle (CBVA) > 25°; McGregor’s slope (MGS) > 20°; or segmental cervical kyphosis > 15° across any 3 vertebrae between C2 and T1. Patients included in the present study underwent surgical intervention for CD and had complete demographic, radiographic, and health-related quality of life (HRQL) data at baseline and up to at least 2 years preoperatively. Patients who underwent revision surgery for any reason were excluded.

Indications for surgery included the following: neurological deficit, persistent severe pain despite conservative measures, spondylotic myelopathy, functionally limiting postural deformity, and airway and/or esophageal compromise. Distal junctional kyphosis was defined by the development of an angle <−10° from the distal end of the fusion construct to the second adjacent distal vertebra, and/or a change in this angle by <−10° from baseline [14]. “Early DJK” denoted patients developing this complication by three months postoperatively. No patients included in this study underwent revision for DJK or any other reason.

2.2. Data Collection

Demographic, radiographic, surgical, and HRQL data were collected. HRQL data collected preoperatively and at all follow-up timepoints include the Neck Disability Index (NDI), Numeric Rating Scale for the neck (NRS-Neck), EuroQol-5 Dimension (EQ-5D), and modified Japanese Orthopaedic Association (mJOA) assessment. The minimally clinically important difference (MCID) for the mJOA was set at 2 based on published values [15,16]. The MCID for NDI was set as 15, which is double the published MCID value, due to our employed NDI score being collected on a 0–100 scale as opposed to 0–50 [17,18]. The NRS-Neck MCID was set as 2 as per previously published values [17,19].

Lateral erect spine radiographs were used to assess radiographic parameters at baseline and follow-up intervals. All images were analyzed with SpineView® (ENSAM, Laboratory of Biomechanics, Paris, France). Spinopelvic radiographic parameters assessed included pelvic tilt (PT), pelvic incidence–lumbar lordosis mismatch (PI-LL), and the sagittal vertical axis (SVA). Cervical spine parameters assessed included cervical lordosis (C2–C7 angle), cervical sagittal vertical axis (cSVA: C2 plumb line relative to the posterosuperior corner of C7), T1 slope (T1S), C2 slope (C2S), T1 slope minus cervical lordosis (TS-CL), and McGregor’s slope (MGS).

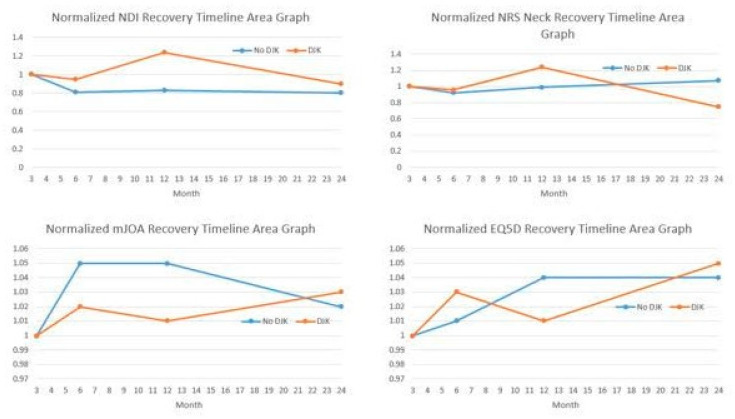

2.3. Development of the Normalized Integrated Health State

Normalized HRQLs were developed and analyzed, permitting the calculation of an integrated health state using the following validated novel area-under-the-curve methodology [20,21]. Collected HRQL metrics at any postoperative timepoint (e.g., 3-month, 6-month, 1-year, and 2-year) were divided by the corresponding preoperative score for each patient. The resulting preoperative normalized HRQL score for all patients was therefore 1, with any follow-up normalized HRQL score being >1, equal to 1, or <1, corresponding to whether the patient improved or deteriorated relative to baseline. Normalized HRQL scores were then plotted on an area graph, with the x-axis representing time (in months, starting at the preoperative interval) and the y-axis representing normalized HRQL scores (Figure 1). Regarding Integrated Health State (IHS) values for varying outcome metrics, lower NDI IH, lower NRS neck his, and higher mJOA IHS scores indicated a better outcome (better recovery process).

Figure 1.

Illustration of recovery kinetics in different patient-reported outcome metrics. EQ5D = EuroQol 5-domain questionnaire; mJOA = modified Japanese Orthopaedic Association; NDI = Neck Disability Index; NRS = Numeric Rating Scale.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Means comparisons tests (t-tests and ANOVA) were used to analyze collected variables, with Pearson chi-square tests used for categorical variables. Multivariable analyses (ANCOVA) were used to determine the differences between groups in achieving the MCID in HRQL score improvements while factoring any baseline and perioperative differences. Multivariable logistic regression analysis assessed associations between DJK development and changes in HRQL outcomes. All analyses were performed using SPSS software (v28.0, IBM Armonk, NY, USA), with significance set to p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Cohort Overview

There were 113 patients included in this study. The mean age was 61.1 ± 16.3 years, the mean body mass index (BMI) was 27.1 ± 5.7 kg/m2, and the mean Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) was 0.75 ± 0.5. In total, 65% of patients were female.

3.2. Surgical Descriptors

The mean amount of levels fused was 5.2 ± 3.5, the mean estimated blood loss (EBL) was 894 ± 564 mL, and the mean length of operation was 405.0 ± 185.1 min. By surgical approach, 7.0% of patients underwent an anterior-only approach, 59.7% underwent posterior-only approach, and 31.3% underwent a combined approach. The most common upper instrumented vertebra (UIV) was C3, and the most common lower instrumented vertebra (LIV) was C7. Overall, 60.4% underwent an osteotomy as part of their procedure (Table 1). DJK patients demonstrated more severe malalignment in cSVA and CBVA at baseline (Table 2). There were no differences in other measured radiographic parameters.

Table 1.

Demographic and surgical factor comparisons.

| DJK | Non-DJK | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 60.3 | 62.2 | 0.355 |

| Gender, % female | 71% female | 61% female | 0.080 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27.0 | 28.3 | 0.311 |

| CCI | 1.11 | 0.95 | 0.684 |

| Levels fused | 7.0 | 6.0 | 0.147 |

| EBL, mL | 1028.3 | 843.9 | 0.052 |

| Operative length, mins | 484.0 | 556.5 | 0.064 |

| Osteotomies, % | 76.5 | 49 | 0.005 |

BMI = body mass index, CCI = Charlson Comorbidity Index; EBL = estimated blood loss.

Table 2.

Baseline radiographic comparisons.

| Parameter | DJK | Non-DJK | p-Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| PT, ° | 12.8 | 19.0 | 0.188 |

| PI, ° | 54 | 53.0 | 0.851 |

| PI-LL, ° | 3.20 | 5.01 | 0.051 |

| TK, ° | −30.8 | −16.8 | 0.071 |

| SVA, mm | −18.9 | −14.5 | 0.535 |

| TS-CL, ° | 28 | 23 | 0.442 |

| CL, ° | −9.5 | −4.5 | 0.117 |

| cSVA, mm | 59 | 43.9 | 0.031 |

| CBVA, ° | −9.5 | −1 | 0.037 |

| C2 slope, ° | 30.2 | 32.2 | 0.169 |

CBVA = chin-brow to vertical angle, CL = cervical lordosis; cSVA = cervical (C2–C7) sagittal vertical axis; PT = pelvic tilt; PI = pelvic incidence; PI-LL = pelvic incidence–lumbar lordosis mismatch; SVA = C7–S1 sagittal vertical axis; TK = T4–T12 thoracic kyphosis, TS-CL = T1 slope-cervical lordosis mismatch.

3.3. Postoperative Distal Junctional Kyphosis

Of the 113 patients included in the analysis, 17 developed DJK and 96 did not. Comparing those that developed DJK and those who did not, age (60.3 vs. 62.2), gender (F: 71.0% vs. 61.0%), BMI (27.0 vs. 28.3 kg/m2), CCI (0.77 vs. 0.98), operating time (484.0 vs. 556.5 min), EBL (1028.3 vs. 843.9 mL), and the presentation of neurologic symptoms (70.6% vs. 76.0%) were similar between groups (p > 0.05). Patients who developed early DJK had more severe preoperative deformity (cervical sagittal vertical axis {cSVA}: 59.0 vs. 43.9 mm, p = 0.031), underwent more osteotomies (76.5% vs. 49.0%, p = 0.005), and underwent more combined approaches (64.7% vs. 26.0%, p = 0.002). There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups with regard to posterior approaches, decompressions, and the amount of levels fused. Following surgery, the rate of complications and the development of neurological symptoms were similar between groups, except that DJK patients experienced more dysphagia (17.7% vs. 4.2%; p = 0.034).

3.4. Recovery Kinetics

There were no significant differences between DJK and non-DJK patients at baseline in NDI, NRS-Neck, mJOA, and EQ5D scores. Non-DJK patients generally trended towards better HRQL scores at 1 year, with no significant differences at 2 years (Table 3). Radiographic metrics similarly did not differ between the groups at the 2-year follow-up (Table 4). DJK patients exhibited worse neck disability (NDI) Integrated Health State recovery from 3 months to 1 year, but these differences subsided when following patients through 2 years (Figure 1). DJK patients had worse NDI, NRS, and mJOA scores at 1 year, but these differences had subsided by the 2-year follow up (Figure 1). Non-DJK patients had higher rates of achieving the MCID in NDI at 3 months (39.5 vs. 28%, p = 0.031) and at 1 year (44 vs. 35%, p = 0.043). However, there were no significant differences at 2 years (46.2 vs. 39.7%, p = 0.051). Similar trends in the MCID for NRS neck scores were seen at 3 months (67.3 vs. 46%, p = 0.012) and 1 year (65.2 vs. 49%, p = 0.033), but not at 2 years (64% vs. 55%, p = 0.054). There were no significant differences between DJK and non-DJK patients with regard to the MCID in the mJOA score at all timepoints. Logistic regression analyses controlling for preop deformity (by cSVA magnitude) and surgical invasiveness (osteotomy and combined approach use) revealed that patients experiencing DJK were more likely to experience worsening from baseline NDI score postoperatively by 3 months (OR 2.11, 95% CI: 1.36–5.81) and at 1 year (OR 1.25, 95% CI: 1.05–1.49, p = 0.035). These trends were not seen for NRS, mJOA, and EQ5D scores.

Table 3.

Health-related quality of life metrics.

| DJK | Non-DJK | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| NDI BL | 54.9 | 57.6 | 0.099 |

| NDI 1Y | 45.6 | 38.2 | 0.046 |

| NDI 2Y | 40 | 37.2 | 0.289 |

| NRS-Neck BL | 7 | 6.5 | 0.743 |

| NRS-Neck 1Y | 4 | 4.4 | 0.048 |

| NRS-Neck 2Y | 6 | 4.7 | 0.162 |

| mJOA BL | 9.8 | 11.2 | 0.671 |

| mJOA 1Y | 11 | 14.5 | 0.023 |

| mJOA 2Y | 13.3 | 14.3 | 0.718 |

| EQ5D BL | 6.7 | 5.6 | 0.882 |

| EQ5D 1Y | 6.7 | 5.8 | 0.245 |

| EQ5D 2Y | 4.5 | 5.3 | 0.468 |

EQ5D = EuroQol 5 domain questionnaire; mJOA = modified Japanese Orthopaedic Association score; NDI = Neck Disability Index; NRS-Neck = Numeric Rating Scale score.

Table 4.

Postoperative radiographic and complication comparisons.

| Parameter | DJK | Non-DJK | p-Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| PT 1Y, ° | 19.2 | 20.4 | 0.844 |

| PT 2Y, ° | 20.6 | 19.6 | 0.111 |

| PI 1Y, ° | 52.9 | 58.6 | 0.501 |

| PI 2Y, ° | 53.9 | 57.6 | 0.690 |

| PI-LL 1Y, ° | 1.11 | 0.75 | 0.352 |

| PI-LL 2Y, ° | 3.5 | 2.6 | 0.071 |

| TK 1Y, ° | −7.3 | −8.1 | 0.665 |

| TK 2Y, ° | −7.5 | −7.3 | 0.822 |

| SVA 1Y, mm | 3.36 | 3.58 | 0.993 |

| SVA 2Y, mm | 2.44 | 1.56 | 0.754 |

| TS-CL 1Y, ° | 24 | 19.9 | 0.470 |

| TS-CL 2Y, ° | 26.9 | 23.5 | 0.628 |

| CL 1Y, ° | 4.7 | 6.2 | 0.332 |

| CL 2Y, ° | 1.25 | 4.3 | 0.132 |

| cSVA 1Y, mm | 16.9 | 19.5 | 0.171 |

| cSVA 2Y, mm | 15.3 | 18.7 | 0.231 |

| CBVA 1Y, ° | −1.9 | −1.3 | 0.075 |

| CBVA 2Y, ° | 1.6 | 1.1 | 0.210 |

| C2 slope 1Y, ° | 20.4 | 18.7 | 0.247 |

| C2 slope 2Y, ° | 23.6 | 20 | 0.601 |

| DJF 2Y, % | 16.5 | 6.3 | 0.015 |

| Neurologic complications 2Y, % | 25.4 | 8 | 0.023 |

CL = cervical lordosis; cSVA = cervical (C2–C7) sagittal vertical axis; DJF = distal junctional failure; PT = pelvic tilt; PI = pelvic incidence; PI-LL = pelvic incidence–lumbar lordosis mismatch; SVA = C7–S1 sagittal vertical axis; TK = T4–T12 thoracic kyphosis; TS-CL = T1 slope-cervical lordosis mismatch.

4. Discussion

The frequency of surgical intervention for CD surgery is increasing due to advancements in technique and patient selection [22]. With the increased frequency of cervical vertebra instrumentation, mechanical failure complications such as distal junctional kyphosis (DJK) are becoming more notable [10]. In the cervical spine specifically, DJK has been defined by the development of an angle <−10° from the distal end of the fusion construct to the second adjacent distal vertebra, and/or a change in this angle by <−10° from baseline [14]. DJK is an important issue to address as it can significantly impact the affected patients’ surgical journey, potentially resulting in increased overall cost and also deterioration in achieved clinical and radiographic improvements. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the differences between patients developing postoperative DJK and their unaffected counterparts, with a view to assessing if DJK patients eventually experienced similar levels of improvements as the non-DJK patients.

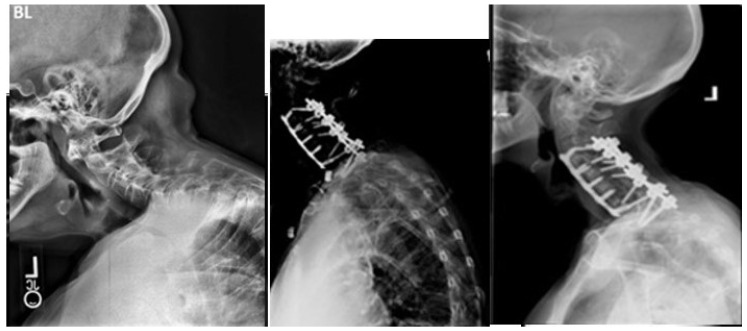

Our study reports a DJK rate of 15% among the patients included in analysis. Perhaps unsurprisingly, patients who developed DJK had significantly worse cervical sagittal malalignment preoperatively (Figure 2 and Figure 3). Excess preoperative malalignment has previously been reported to be predictive of DJK development [9,10,14,23]. Passias et al. studied 101 patients undergoing CD surgery and reported that excessive preoperative malalignment beyond certain thresholds of cervical lordosis (<−12°, cSVA > 56.3 mm, and TS-CL > 36.4°) resulted in a five to six times increased risk for DJK [14]. Patients who developed DJK also underwent a significantly higher frequency of osteotomies and combined surgical approaches, compared to non-DJK patients. Combined surgical approaches and the Smith Peterson osteotomy have previously been reported as notable predictors of DJK [11,14].

Figure 2.

A 71-year-old female from the DJK group. Images from left-to-right: preoperative, immediate postoperative, and 3-month postoperative X-rays. History of progressive right-sided neck pain with progressive radiculopathy and myelopathy. Symptoms unresolved with conservative measures. Underwent C3–C7 ACDF with C3-T1 posterior fusion. Symptoms initially showed some improvement up to 6 weeks, before showing gradual worsening.

Figure 3.

A 70-year-old male from the non-DJK group. Images from left-to-right: preoperative, immediate postoperative, and 3-month postoperative X-rays. History of intractable neck pain with sensory and motor right upper limb deficits. Had also previously undergone L2-to-pelvis fusion for degenerative lumbar disc disease. Underwent C3–C5 and C6–C7 ACDF with C3-T2 posterior fusion. Symptoms showed improvement and radiographic alignment was maintained without evidence of DJK.

Predictably, patients in our study who developed early DJK still exhibited significantly worse cervical sagittal malalignment (cSVA) than their unaffected counterparts at two years. Both preoperative and postoperative malalignment have been associated with increased rates of DJK [9,24]. These patients also exhibited consistently worse HRQL metrics (NDI and EQ-5D) at follow up until one year. Interestingly, these differences were insignificant at two years postoperatively. This indicates that despite these patients still displaying radiographic evidence of malalignment after two years, their overall levels of disability and symptomaticity had eventually improved to comparable levels with their non-DJK counterparts. This was especially evident in the patients who underwent revision surgery due to DJK, who also achieved comparable HRQL outcomes at two years. We have not been able to identify factors contributing to this improvement between one year and two years postoperatively. Previous studies into mechanical failure after cervical vertebra instrumentation predominantly involved follow-up until one-year postoperatively [6,9,10,14,24]. Future studies will need to include longer term follow-up in order to further shed light on this.

This study is not without limitations. The retrospective nature combined with relatively small sample sizes may limit the generalizability of findings. The relatively limited sample size may potentially result in restricted clinical variation and truncation in certain areas. Additionally, due to the heterogenous nature of CD, there is potential for limitations in the applicability of radiographic parameters employed in analyzing this pathology. The heterogeneous nature of CD does not allow for a more in-depth analysis of focal preoperative malalignments either. We have not included an analysis of additional therapeutic modalities used postoperatively either. Such an analysis may have shed some light on the HRQL improvements noted in the DJK patients between one and two years postoperatively.

5. Conclusions

Despite exhibiting similar preoperative health-related quality of life metrics, patients who developed early postoperative DJK exhibited worse postoperative neck disability following the development of their DJK, when compared with their unaffected counterparts. These differences had subsided by the 2-year follow-up, highlighting the prolonged but eventually successful course of many DJK patients after CD surgery without needing to undergo revision surgery.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.G.P.; Methodology, O.O.O., T.W., A.D., M.G., N.L. and P.G.P.; Formal analysis, O.O.O., B.I., A.D., J.M.M., M.G. and N.L.; Investigation, O.O.O., B.I. and P.G.P.; Data curation, O.O.O., B.I., T.W. and J.M.M.; Writing—original draft, O.O.O., B.I., T.W., A.D., J.M.M., M.G. and N.L.; Writing—review & editing, O.O.O. and P.G.P.; Supervision, P.G.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Institutional Review Board approval (NYU School of medicine, protocol code S13-00422, date of approval 3 August 2013) was obtained before enrolling patients in the prospective database. Informed consent was obtained from each patient prior to enrollment.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study is not publicly available due to Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act and Institutional restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding Statement

This research received no external funding.

Footnotes

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

References

- 1.Kim H.J., Virk S., Elysee J., Passias P., Ames C., Shaffrey C., Mundis G., Protopsaltis T., Gupta M., Klineberg E., et al. The morphology of cervical deformities: A two-step cluster analysis to identify cervical deformity patterns. J. Neurosurg. Spine SPI. 2020;32:353–359. doi: 10.3171/2019.9.SPINE19730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koller H., Ames C., Mehdian H., Bartels R., Ferch R., Deriven V., Toyone H., Shaffrey C., Smith J., Hitzl W., et al. Characteristics of deformity surgery in patients with severe and rigid cervical kyphosis (CK): Results of the CSRS-Europe multi-centre study project. Eur. Spine J. 2019;28:324–344. doi: 10.1007/s00586-018-5835-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith J.S., Line B., Bess S., Shaffrey C.I., Kim H.J., Mundis G., Scheer J.K., Klineberg E., O’brien M., Hostin R., et al. The Health Impact of Adult Cervical Deformity in Patients Presenting for Surgical Treatment: Comparison to United States Population Norms and Chronic Disease States Based on the EuroQuol-5 Dimensions Questionnaire. Neurosurgery. 2017;80:716–725. doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyx028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ailon T., Smith J.S., Shaffrey I.C., Kim H.J., Mundis G., Gupta M., Klineberg E., Schwab F., Lafage V., Lafage R., et al. Outcomes of Operative Treatment for Adult Cervical Deformity: A Prospective Multicenter Assessment with 1-Year Follow-up. Neurosurgery. 2018;83:1031–1039. doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyx574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zuckerman S.L., Devin C.J. Outcomes and value in elective cervical spine surgery: An introductory and practical narrative review. J. Spine Surg. 2020;6:89–105. doi: 10.21037/jss.2020.01.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Passias P.G., Horn S.R., Oh C., Lafage R., Lafage V., Smith J.S., Line B., Protopsaltis T.S., Yagi M., Bortz C.A., et al. Predicting the Occurrence of Postoperative Distal Junctional Kyphosis in Cervical Deformity Patients. Neurosurgery. 2020;86:E38–E46. doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyz347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akıntürk N., Zileli M., Yaman O. Complications of adult spinal deformity surgery: A literature review. J. Craniovertebral Junction Spine. 2022;13:17–26. doi: 10.4103/jcvjs.jcvjs_159_21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang P.Y., Chen C.W., Lee Y.F., Hu M.H., Wang T.M., Lai P.L., Yang S.H. Distal Junctional Kyphosis after Posterior Spinal Fusion in Lenke 1 and 2 Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis-Exploring Detailed Features of the Sagittal Stable Vertebra Concept. Glob. Spine J. 2023;13:1112–1119. doi: 10.1177/21925682211019692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee J.J., Park J.H., Oh Y.G., Shin H.K., Park B.G. Change in the Alignment and Distal Junctional Kyphosis Development after Posterior Cervical Spinal Fusion Surgery for Cervical Spondylotic Myelopathy–Risk Factor Analysis. J. Korean Neurosurg. Soc. 2022;65:549–557. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2021.0192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lafage R., Smith J.S., Soroceanu A., Ames C., Passias P., Shaffrey C., Mundis G., Alshabab B.S., Protopsaltis T., Klineberg E., et al. Predicting Mechanical Failure Following Cervical Deformity Surgery: A Composite Score Integrating Age-Adjusted Cervical Alignment Targets. Glob. Spine J. 2022;13:2432–2438. doi: 10.1177/21925682221086535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pierce K.E., Passias P.G., Lafage V., Lafage R., Kim H.J., Daniels A.H., Eastlack R.K., Klineberg E.O., Line B., Protopsaltis T.S., et al. P48. Disparities in etiology, clinical presentation and determinants for distal junctional kyphosis based on timing of occurrence: Are we treating two separate issues? Spine J. 2020;20((Suppl. S9)):S169. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2020.05.446. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Echt M., Ranson W., Steinberger J., Yassari R., Cho S.K. A Systematic Review of Treatment Strategies for the Prevention of Junctional Complications after Long-Segment Fusions in the Osteoporotic Spine. Glob. Spine J. 2021;11:792–801. doi: 10.1177/2192568220939902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao J., Chen K., Zhai X., Chen K., Li M., Lu Y. Incidence and risk factors of proximal junctional kyphosis after internal fixation for adult spinal deformity: A systematic evaluation and meta-analysis. Neurosurg. Rev. 2021;44:855–866. doi: 10.1007/s10143-020-01309-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Passias P.G., Vasquez-Montes D., Poorman G.W., Protopsaltis T., Horn S.R., Bortz C.A., Segreto F., Diebo B., Ames C., Smith J., et al. Predictive model for distal junctional kyphosis after cervical deformity surgery. Spine J. Off. J. N. Am. Spine Soc. 2018;18:2187–2194. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2018.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kato S., Oshima Y., Matsubayashi Y., Taniguchi Y., Tanaka S., Takeshita K. Minimum Clinically Important Difference and Patient Acceptable Symptom State of Japanese Orthopaedic Association Score in Degenerative Cervical Myelopathy Patients. Spine. 2019;44:691–697. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000002928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soroceanu A., Lau D., Kelly M.P., Passias P.G., Protopsaltis T.S., Gum J.L., Lafage V., Kim H.-J., Scheer J.K., Gupta M., et al. Establishing the minimum clinically important difference in Neck Disability Index and modified Japanese Orthopaedic Association scores for adult cervical deformity. J. Neurosurg. Spine. 2020;33:441–445. doi: 10.3171/2020.3.SPINE191232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carreon L.Y., Glassman S.D., Campbell M.J., Anderson P.A. Neck Disability Index, short form-36 physical component summary, and pain scales for neck and arm pain: The minimum clinically important difference and substantial clinical benefit after cervical spine fusion. Spine J. Off. J. N. Am. Spine Soc. 2010;10:469–474. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Young B.A., Walker M.J., Strunce J.B., Boyles R.E., Whitman J.M., Childs J.D. Responsiveness of the Neck Disability Index in patients with mechanical neck disorders. Spine J. Off. J. N. Am. Spine Soc. 2009;9:802–808. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khan I., Pennings J.S., Devin C.J., Oleisky E.R., Bydon M., Asher A.M.B., Archer K.R. Clinically Meaningful Improvement Following Cervical Spine Surgery: 30% Reduction Versus Absolute Point-change MCID Values. Spine. 2021;46:717–725. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000003887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu S., Tetreault L., Fehlings M.G., Challier V., Smith J.S., Shaffrey C.I., Arnold P.M., Scheer J.K., Chapman J.R., Kopjar B., et al. Novel Method Using Baseline Normalization and Area under the Curve to Evaluate Differences in Outcome Between Treatment Groups and Application to Patients with Cervical Spondylotic Myelopathy Undergoing Anterior Versus Posterior Surgery. Spine. 2015;40:E1299–E1304. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000001152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Segreto A.F., Lafage V., Lafage R., Smith J.S., Line B.G., Eastlack R.K., Scheer J.K., Chou D., Frangella N.J., Horn S.R., et al. Recovery Kinetics: Comparison of Patients Undergoing Primary or Revision Procedures for Adult Cervical Deformity Using a Novel Area under the Curve Methodology. Neurosurgery. 2019;85:E40–E51. doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyy435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith J.S., Shaffrey C.I., Bess S., Shamji M.F., Brodke D., Lenke L.G., Fehlings M.G., Lafage V., Schwab F., Vaccaro A.R., et al. Recent and Emerging Advances in Spinal Deformity. Neurosurgery. 2017;80:S70–S85. doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyw048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith J.S., Buell T.J., Shaffrey C., Kim H.J., Klineberg E., Protopsaltis T., Passias P., Mundis G.M., Eastlack R., Deviren V., et al. Prospective multicenter assessment of complication rates associated with adult cervical deformity surgery in 133 patients with minimum 1-year follow-up. J. Neurosurg. Spine. 2020;33:588–600. doi: 10.3171/2020.4.SPINE20213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ayres E.W., Protopsaltis T.S., Ani F., Lafage R., Walia A., Mundis G.M., Jr., Smith J.S., Hamilton D.K., Klineberg E.O., Sciubba D.M., et al. Predicting the Magnitude of Distal Junctional Kyphosis Following Cervical Deformity Correction. Spine. 2023;48:232–239. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000004492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study is not publicly available due to Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act and Institutional restrictions.