Abstract

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) glycoprotein gp350/gp220 association with cellular CD21 facilitates virion attachment to B lymphocytes. Membrane fusion requires the additional interaction between virion gp42 and cellular HLA-DR. This binding is thought to catalyze membrane fusion through a further association with the gp85-gp25 (gH-gL) complex. Cell lines expressing CD21 but lacking expression of HLA class II molecules are resistant to infection by a recombinant EBV expressing enhanced green fluorescent protein. Surface expression of HLA-DR, HLA-DP, or HLA-DQ confers susceptibility to EBV infection on resistant cells that express CD21. Therefore, HLA-DP or HLA-DQ can substitute for HLA-DR and serve as a coreceptor in EBV entry.

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection is prevalent in all human populations and is linked to a variety of human diseases. EBV causes infectious mononucleosis and is associated with a variety of hemopoietic malignancies, such as Burkitt's lymphoma, some forms of Hodgkin's lymphoma, and adult T-cell leukemia (17, 24, 29). EBV is also etiologically associated with two diseases of epithelial cell origin, nasopharyngeal carcinoma and oral hairy leukoplakia (17, 22, 29). In vitro, the EBV host range is largely restricted to B cells. The entry of EBV into a B cell occurs through a cascade of events that requires the association of multiple cellular and viral factors. The initial event required for entry is the interaction of the major viral envelope glycoprotein, gp350, with complement receptor type 2 molecule CD21, previously referred to as CR2 (27, 33). Virion penetration of the B-cell membrane requires the additional interaction of the ternary EBV glycoprotein gp85-gp25-gp42 complex with its cellular ligand (20, 35). gp85 and gp25 are the EBV homologs of herpes simplex virus gH and gL, respectively. gp42 can interact with the HLA class II protein HLA-DR (32). The ability of EBV to utilize HLA-DR as a coreceptor for entry is demonstrated by the observation that certain B-cell lines lacking HLA-DR expression are not susceptible to superinfection unless the expression of HLA-DR is restored (19).

Studies of EBV infection have been limited by the lack of a recombinant EBV bearing a reporter gene. Such studies typically utilize cellular transformation, immortalization, or the detection of EBV antigens as indicators of viral infection. To investigate the dependence of EBV infection on cellular receptors, a recombinant EBV reporter virus expressing enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP), designated EBfaV-GFP, has been constructed (30). Two CD21-positive, HLA class II-negative cell lines, HPB-ALL and 721.174, were used to determine if the introduction of HLA-DP and/or HLA-DQ molecules to the surfaces of HLA class II-deficient cells could substitute for HLA-DR and mediate EBV entry. Here we show that surface expression of HLA-DP or HLA-DQ is sufficient to render CD21-expressing cells susceptible to infection by EBfaV-GFP.

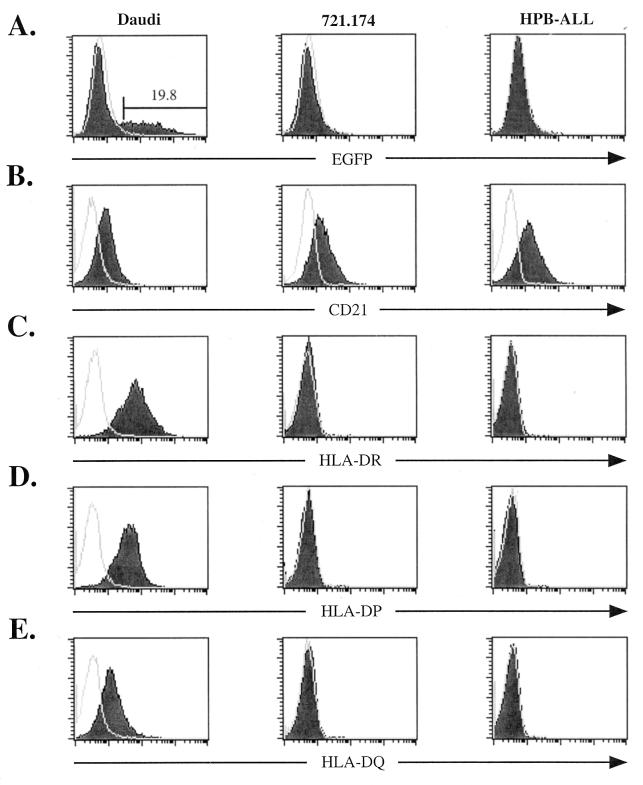

EBfaV-GFP was used to screen a panel of CD21-expressing cell lines. A Burkitt's lymphoma cell line, Daudi (18), is one of many cell lines that not only abundantly express CD21 but also are readily infectible by EBfaV-GFP as measured by EGFP expression within the cell (Fig. 1A and B). Two other cell lines, 721.174, a lymphoblastoid cell line (9), and HPB-ALL, an immature T-cell lymphoma cell line (26), are resistant to infection by EBfaV-GFP but express abundant CD21 (Fig. 1A and B). A previous study has indicated that EBV can enter HPB-ALL cells (28); however, our experiments demonstrate that HPB-ALL cells are not readily infectible (Fig. 1A). No EGFP expression is detected in HPB-ALL cells even when cultures are grown for 5 days after exposure to EBfaV-GFP (data not shown). CD21 expression does not correlate with efficiency of infection, as HPB-ALL cells express a higher level of CD21 than do Daudi cells (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

Susceptibility of CD21-expressing cell lines to EBfaV-GFP infection corresponds with surface expression of HLA class II molecules. (A) Daudi, 721.174, or HPB-ALL cells (106) were infected with 3 × 105 green units as previously described (31). Twenty-four hours after infection, cells were analyzed for EGFP fluorescence by flow cytometry using a FacsCalibur (Becton Dickinson). Unshaded histograms represent EGFP fluorescence of cells in the absence of exposure to EBfaV-GFP. Shaded histograms represent EGFP fluorescence after exposure to the virus. The number above the marked region represents the percentage of Daudi cells infected. (B) Surface expression of CD21 on Daudi, 721.174, or HPB-ALL cells, analyzed by flow cytometry using the monoclonal antibody HB5 (34). Isotype-specific monoclonal antibodies were used to detect the surface expression of HLA-DR (TÜ36) (C), HLA-DP (HI43) (D), and HLA-DQ (Ia3) (E) on Daudi, 721.174, and HPB-ALL cells. Unshaded histograms (B to E) represent cells stained with an immunoglobulin isotype-matched control immunoglobulin G2a antibody recognized by a secondary goat anti-mouse antibody conjugated to allophycocyanin (Caltag Laboratories). Shaded histograms represent cells stained with the appropriate antibody recognized by the same secondary antibody.

Since HLA-DR has been shown to be important for the infection of B cells by EBV, surface expression of HLA-DR on 721.174 and HPB-ALL cells was measured by flow cytometry using an HLA-DR-specific monoclonal antibody (TÜ36; Pharmingen). As shown in Fig. 1C, neither the 721.174 nor the HPB-ALL cell line expresses detectable levels of HLA-DR. In contrast, Daudi cells liberally express HLA-DR (Fig. 1C). Surface expression measured by flow cytometry on Daudi cells by using isotype-specific monoclonal antibodies for HLA-DP (HI43; Pharmingen) and HLA-DQ (Ia3; ICN Biomedicals) illustrates that Daudi cells express all three class II molecules (Fig. 1D and E). This phenotype is similar to that of another B-cell line, Raji (13), that expresses all three class II isotypes and is also readily infectible by EBfaV-GFP in culture (data not shown). Conversely, both 721.174 and HPB-ALL cells lack expression of HLA-DP and HLA-DQ (Fig. 1D and E). The observation that Daudi and Raji cells express all three class II isotypes and are efficiently infected by EBfaV-GFP raises the possibility of a previously undefined role for HLA-DP and HLA-DQ in EBV entry.

Transient transfection of different class II molecules was used to determine whether HLA-DP and HLA-DQ could substitute for HLA-DR and mediate EBfaV-GFP entry. In order to perform these assays, appropriate expression vectors were constructed. The cDNAs encoding HLA-DRα and HLA-DPα126 were excised from pRSV.5(gpt) (23) with EcoRI and BamHI endonucleases and were inserted into pSG5 (Stratagene). Similarly, the cDNAs encoding HLA-DRβ008 and HLA-DPβ003 were excised from pRSV.5(neo) (23) with EcoRI and BamHI endonucleases and were inserted into pSG5. The cDNAs for HLA-DQα*0501 and HLA-DQβ*0201 were created by PCR amplification of cDNAs contained in pLNLc6 (14) by using 5′ primers that contained an EcoRI site incorporated into the 5′ untranslated region and 3′ primers that contained a BamHI site incorporated into the 3′ end of the cDNA downstream of the stop codon. HLA-DQ clones created in this manner were sequenced on both strands, and comparison to HLA-DQ sequences present in available databases ensured that no mutations were introduced by PCR.

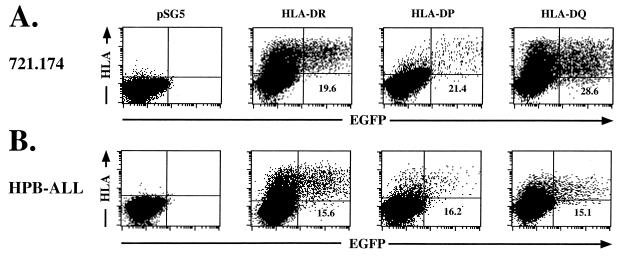

Isotype-matched HLA-DR, -DP, and -DQ alpha and beta chain or pSG5 vector control DNA was electroporated into 721.174 cells. Twenty-four hours after electroporation, 1 × 106 cells were exposed to an EBfaV-GFP stock containing approximately 3 × 105 “green” units. One green unit is defined as the amount of EBfaV-GFP stock necessary to give rise to one EGFP fluorescent Daudi cell (31). After an additional 24 h, cells were analyzed by two-color flow cytometry using a pan-class II antibody (TÜ39; Pharmingen) against HLA-DR, -DP, and -DQ. Analysis by flow cytometry of 721.174 cells electroporated with HLA-DR revealed that expression of HLA-DR renders these cells susceptible to infection by EBfaV-GFP as measured by EGFP expression (Fig. 2A). Likewise, expression of HLA-DP or -DQ also renders both cell lines infectible (Fig. 2A). Further, the percentage of cells that express HLA-DR and are infectible is similar to the percentage of cells that express HLA-DP or -DQ and are infectible (Fig. 2A). The number of cells expressing HLA class II isotypes at the time of infection was similar to that observed when the number of cells infected was monitored by two-color flow cytometry (data not shown). In cells transfected with the pSG5 vector control, no class II protein was expressed, and no EBfaV-GFP infection was apparent (Fig. 2A). At no time did any EGFP accumulate in these cells, even after a 5-day incubation period.

FIG. 2.

Expression of HLA-DR, -DP, or -DQ mediates EBV entry into 721.174 and HPB-ALL cells. Daudi or HPB-ALL cells (106) electroporated with HLA-DR, HLA-DP, or HLA-DQ were infected with EBfaV-GFP and analyzed by two-color flow cytometry. The flow cytometer was gated for EGFP fluorescence and class II expression using a pan-class II antibody, TÜ39, detected by a goat anti-mouse allophycocyanin-conjugated secondary antibody. pSG5-electroporated cells were exposed to EBfaV-GFP and stained identically to class II-transfected cells. The number given in the lower right quadrant represents the percentage of cells expressing the appropriate class II molecule which are infected by EBfaV-GFP. Each plot shows 40,000 events.

To confirm that HLA-DP or -DQ can substitute for HLA-DR as a cofactor in EBV entry, class II molecules were expressed on cells of non-B-cell origin. Isotype-matched HLA-DR, -DP, and -DQ alpha and beta chain or pSG5 vector control DNA was transfected into HPB-ALL cells, which were infected as described above. Two-color flow cytometric analysis again demonstrated that all three class II isotypes are capable of mediating entry (Fig. 2B). Moreover, HPB-ALL and 721.174 cells expressing class II molecules become infected at a similar frequency, indicating that it is unlikely that B-cell-specific factors besides CD21 are required for the entry of EBV into B cells (Fig. 2). It is possible that because the HPB-ALL cell line is derived from a lymphoma, a B-cell-specific molecule is aberrantly expressed; however, surface expression of HLA-DR and CD21 is sufficient to render multiple cell lines susceptible to EBV infection (K. M. Haan, unpublished data).

The entry of viruses into cells is a complex process, with several viruses having been shown to require multiple cellular receptors to facilitate virion attachment and penetration. Although it has been reported that EBV can infect CD21-positive, HLA class II-negative cells (1, 21, 28), quantification of EBV infection efficiency as assayed here by the measurement of EGFP expression has not been demonstrated. Our results suggest that CD21-positive, HLA class II-negative cells, such as 721.174 and HPB-ALL cells, show low susceptibility to infection in the absence of a coreceptor such as HLA class II. Efficient infection by EBV can occur only if these cell lines are transfected with HLA class II molecules (Fig. 2). In addition to lymphoid cells, EBV also causes disease in epithelial cells. Since epithelial cells do not express HLA class II molecules, the quantification of EBV infection of epithelial cell lines, such as SVK-CR2 (21), can now be pursued to determine receptors that are important for epithelial cell entry.

Herpes simplex virus can use several dissimilar cofactors to catalyze penetration of the host cell membrane (16, 25). Human immunodeficiency virus utilizes a number of chemokine receptors as cofactors to facilitate membrane fusion (2, 7, 10–12, 15). The ability of EBV to enter cells via all three isotypes of HLA class II molecules emphasizes the concept that some viruses can enter cells through multiple entry mediators. Tissue specificity of HLA class II genes is typically restricted to immune cells, including B cells, dendritic cells, activated T cells, macrophages, and the thymic epithelial cells. Additionally, transcription of class II genes may be induced by gamma interferon in many cell types (5, 8), potentially allowing these cells to present antigens to T cells and become infected by EBV. HLA-DQ is particularly sensitive to induction by gamma interferon in class II-positive cells (3, 4), while the induction of HLA-DP and -DR occurs in HLA class II-negative cells (8). Gamma interferon is produced in response to many viral infections. Increased gamma interferon levels in response to EBV infection may serve to increase HLA-DQ levels on B cells and enhance infectivity. Alternatively, the inducible expression of HLA-DP and -DR upon class II-negative cells may facilitate infection of cell types that express low levels of CD21.

The finding that EBV does not rely upon a particular isotype of class II molecule to mediate infection implies that the host cell range of EBV includes cells other than those explicitly expressing HLA-DR. Given the high prevalence of EBV infection in humans and the multitude of HLA class II alleles, it is probable that EBV entry does not require specific class II allele combinations and that many allele pairs within each locus can serve as cofactors for entry. HLA class II molecules exhibit between 65 and 70% amino acid identity but are highly polymorphic within the region from amino acids 48 to 108, which has been shown to be crucial for gp42 interaction with the HLA-DR beta chain (32). The most prominent structural feature within this region is the α-helix, which stretches from amino acids 56 to 90 and composes one side of the peptide binding pocket (6). This indicates that the α-helix structural motif could encompass the gp42 binding pocket for HLA class II molecules. Of interest, this α-helix has a pronounced kink compared to its HLA class I counterpart (6). The highly polymorphic nature of the gp42 binding region of HLA class II molecules also suggests that although many alleles may mediate EBV infection, other alleles may not encode the residues necessary to facilitate EBV entry. Considering this, it will be important to determine what amino acids within this region are vital to the entry process and to determine if certain class II alleles intrinsically offer natural resistance to EBV infection.

Acknowledgments

We thank the people in the laboratories of R. Longnecker and P. Spear for providing advice and help. We also thank E. O. Long, R. M. Hershberg, and L. Hutt-Fletcher for the gifts of invaluable reagents and advice.

K.M.H. is supported by the training program in the Cellular and Molecular Basis of Disease (T32 GM08061) from the National Institutes of Health. R.L. is a Scholar of the Leukemia Society of America and is supported by Public Health Service grants CA62234 and CA73507 from the National Cancer Institute and DE13127 from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahearn J M, Hayward S D, Hickey J C, Fearon D T. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection of murine L cells expressing recombinant human EBV/C3d receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:9307–9311. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.23.9307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alkhatib G, Combadiere C, Broder C C, Feng Y, Kennedy P E, Murphy P M, Berger E A. CC CKR5: a RANTES, MIP-1alpha, MIP-1beta receptor as a fusion cofactor for macrophage-tropic HIV-1. Science. 1996;272:1955–1958. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5270.1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ameglio F, Capobianchi M R, Dolei A, Tosi R. Differential effects of gamma interferon on expression of HLA class II molecules controlled by the DR and DC loci. Infect Immun. 1983;42:122–125. doi: 10.1128/iai.42.1.122-125.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Basham T, Smith W, Lanier L, Morhenn V, Merigan T. Regulation of expression of class II major histocompatibility antigens on human peripheral blood monocytes and Langerhans cells by interferon. Hum Immunol. 1984;10:83–93. doi: 10.1016/0198-8859(84)90075-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Basta P V, Sherman P A, Ting J P. Identification of an interferon-gamma response region 5′ of the human histocompatibility leukocyte antigen DR alpha chain gene which is active in human glioblastoma multiforme lines. J Immunol. 1987;138:1275–1280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown J H, Jardetzky T S, Gorga J C, Stern L J, Urban R G, Strominger J L, Wiley D C. Three-dimensional structure of the human class II histocompatibility antigen HLA-DR1. Nature. 1993;364:33–39. doi: 10.1038/364033a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choe H, Farzan M, Sun Y, Sullivan N, Rollins B, Ponath P D, Wu L, Mackay C R, LaRosa G, Newman W, Gerard N, Gerard C, Sodroski J. The beta-chemokine receptors CCR3 and CCR5 facilitate infection by primary HIV-1 isolates. Cell. 1996;85:1135–1148. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81313-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collins T, Korman A J, Wake C T, Boss J M, Kappes D J, Fiers W, Ault K A, Gimbrone M A, Jr, Strominger J L, Pober J S. Immune interferon activates multiple class II major histocompatibility complex genes and the associated invariant chain gene in human endothelial cells and dermal fibroblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:4917–4921. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.15.4917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeMars R, Chang C C, Shaw S, Reitnauer P J, Sondel P M. Homozygous deletions that simultaneously eliminate expressions of class I and class II antigens of EBV-transformed B-lymphoblastoid cells. I. Reduced proliferative responses of autologous and allogeneic T cells to mutant cells that have decreased expression of class II antigens. Hum Immunol. 1984;11:77–97. doi: 10.1016/0198-8859(84)90047-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deng H, Liu R, Ellmeier W, Choe S, Unutmaz D, Burkhart M, Di Marzio P, Marmon S, Sutton R E, Hill C M, Davis C B, Peiper S C, Schall T J, Littman D R, Landau N R. Identification of a major co-receptor for primary isolates of HIV-1. Nature. 1996;381:661–666. doi: 10.1038/381661a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doranz B J, Rucker J, Yi Y, Smyth R J, Samson M, Peiper S C, Parmentier M, Collman R G, Doms R W. A dual-tropic primary HIV-1 isolate that uses fusin and the beta-chemokine receptors CKR-5, CKR-3, and CKR-2b as fusion cofactors. Cell. 1996;85:1149–1158. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81314-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dragic T, Litwin V, Allaway G P, Martin S R, Huang Y, Nagashima K A, Cayanan C, Maddon P J, Koup R A, Moore J P, Paxton W A. HIV-1 entry into CD4+ cells is mediated by the chemokine receptor CC-CKR-5. Nature. 1996;381:667–673. doi: 10.1038/381667a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Epstein M A, Achong B G, Barr Y M, Zajac B, Henle G, Henle W. Morphological and virological investigations on cultured Burkitt tumor lymphoblasts (strain Raji) J Nat Cancer Inst. 1966;37:547–559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ettinger R A, Liu A W, Nepom G T, Kwok W W. Exceptional stability of the HLA-DQA1*0102/DQB1*0602 alpha beta protein dimer, the class II MHC molecule associated with protection from insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Immunol. 1998;161:6439–6445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feng Y, Broder C C, Kennedy P E, Berger E A. HIV-1 entry cofactor: functional cDNA cloning of a seven-transmembrane, G protein-coupled receptor. Science. 1996;272:872–877. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5263.872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Geraghty R J, Krummenacher C, Cohen G H, Eisenberg R J, Spear P G. Entry of alphaherpesviruses mediated by poliovirus receptor-related protein 1 and poliovirus receptor. Science. 1998;280:1618–1620. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5369.1618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kieff E. Epstein Barr virus and its replication. In: Fields B, Knipe D, Howley P, editors. Fundamental virology. New York, N.Y: Raven Press; 1996. pp. 1109–1162. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klein G, Clements G, Zeuthen J, Westman A. Somatic cell hybrids between human lymphoma lines. II. Spontaneous and induced patterns of the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) cycle. Int J Cancer. 1976;17:715–724. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910170605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li Q, Spriggs M K, Kovats S, Turk S M, Comeau M R, Nepom B, Hutt-Fletcher L M. Epstein-Barr virus uses HLA class II as a cofactor for infection of B lymphocytes. J Virol. 1997;71:4657–4662. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.6.4657-4662.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Q, Turk S M, Hutt-Fletcher L M. The Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) BZLF2 gene product associates with the gH and gL homologs of EBV and carries an epitope critical to infection of B cells but not of epithelial cells. J Virol. 1995;69:3987–3994. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.7.3987-3994.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li Q X, Young L S, Niedobitek G, Dawson C W, Birkenbach M, Wang F, Rickinson A B. Epstein-Barr virus infection and replication in a human epithelial cell system. Nature. 1992;356:347–350. doi: 10.1038/356347a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liebowitz D. Pathogenesis of Epstein-Barr virus. In: McCance D J, editor. Human tumor viruses. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1998. pp. 175–199. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Long E O, Rosen-Bronson S, Karp D R, Malnati M, Sekaly R P, Jaraquemada D. Efficient cDNA expression vectors for stable and transient expression of HLA-DR in transfected fibroblast and lymphoid cells. Hum Immunol. 1991;31:229–235. doi: 10.1016/0198-8859(91)90092-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Longnecker R. Molecular biology of Epstein-Barr virus. In: McCance D J, editor. Human tumor viruses. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1998. pp. 135–174. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Montgomery R I, Warner M S, Lum B J, Spear P. Herpes simplex type 1 entry mediated by a novel member of the TNF/NGF receptor family. Cell. 1996;87:427–436. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81363-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morikawa S, Tatsumi E, Baba M, Harada T, Yasuhira K. Two E-rosette-forming lymphoid cell lines. Int J Cancer. 1978;21:166–170. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910210207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nemerow G R, Houghten R A, Moore M D, Cooper N R. Identification of an epitope in the major envelope protein of Epstein-Barr virus that mediates viral binding to the B lymphocyte EBV receptor (CR2) Cell. 1989;56:369–377. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90240-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paterson R L, Kelleher C, Amankonah T D, Streib J E, Xu J W, Jones J F, Gelfand E W. Model of Epstein-Barr virus infection of human thymocytes: expression of viral genome and impact on cellular receptor expression in the T-lymphoblastic cell line, HPB-ALL. Blood. 1995;85:456–464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rickinson A, Kieff E. Epstein-Barr virus. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, Chanock R M, Melnick J L, Monath T P, Roizman B, Straus S E, editors. Fields virology. 3rd ed. Vol. 2. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven; 1996. pp. 2397–2446. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Speck P, Kline K A, Cheresh P, Longnecker R. Epstein-Barr virus lacking latent membrane protein 2 immortalizes B cells with efficiency indistinguishable from wild-type virus. J Gen Virol. 1999;80:2193. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-8-2193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Speck P, Longnecker R. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection visualized by EGFP expression demonstrates dependence on known mediators of EBV entry. Arch Virol. 1999;144:1123–1137. doi: 10.1007/s007050050574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spriggs M K, Armitage R J, Comeau M R, Strockbine L, Farrah T, Macduff B, Ulrich D, Alderson M R, Müllberg J, Cohen J I. The extracellular domain of the Epstein-Barr virus BZLF2 protein binds the HLA-DR β chain and inhibits antigen presentation. J Virol. 1996;70:5557–5563. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.8.5557-5563.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tanner J, Weis J, Fearon D, Whang Y, Kieff E. Epstein-Barr virus gp350/220 binding to the B lymphocyte C3d receptor mediates adsorption, capping, and endocytosis. Cell. 1987;50:203–213. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90216-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tedder T F, Goldmacher V S, Lambert J M, Schlossman S F. Epstein Barr virus binding induces internalization of the C3d receptor: a novel immunotoxin delivery system. J Immunol. 1986;137:1387–1391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang X, Hutt-Fletcher L M. Epstein-Barr virus lacking glycoprotein gp42 can bind to B cells but is not able to infect. J Virol. 1998;72:158–163. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.1.158-163.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]