Heart failure is the end stage of all diseases of the heart and is a major cause of morbidity and mortality. It is estimated to account for about 5% of admissions to hospital medical wards, with over 100 000 annual admissions in the United Kingdom.

“The very essence of cardiovascular practice is the early detection of heart failure”Sir Thomas Lewis, 1933

Some definitions of heart failure

“A condition in which the heart fails to discharge its contents adequately” (Thomas Lewis, 1933)

“A state in which the heart fails to maintain an adequate circulation for the needs of the body despite a satisfactory filling pressure” (Paul Wood, 1950)

“A pathophysiological state in which an abnormality of cardiac function is responsible for the failure of the heart to pump blood at a rate commensurate with the requirements of the metabolising tissues” (E Braunwald, 1980)

“Heart failure is the state of any heart disease in which, despite adequate ventricular filling, the heart's output is decreased or in which the heart is unable to pump blood at a rate adequate for satisfying the requirements of the tissues with function parameters remaining within normal limits” (H Denolin, H Kuhn, H P Krayenbuehl, F Loogen, A Reale, 1983)

“A clinical syndrome caused by an abnormality of the heart and recognised by a characteristic pattern of haemodynamic, renal, neural and hormonal responses” (Philip Poole-Wilson, 1985)

“[A] syndrome ... which arises when the heart is chronically unable to maintain an appropriate blood pressure without support” (Peter Harris, 1987)

“A syndrome in which cardiac dysfunction is associated with reduced exercise tolerance, a high incidence of ventricular arrhythmias and shortened life expectancy” (Jay Cohn, 1988)

“Abnormal function of the heart causing a limitation of exercise capacity” or “ventricular dysfunction with symptoms” (anonymous and pragmatic)

“Symptoms of heart failure, objective evidence of cardiac dysfunction and response to treatment directed towards heart failure” (Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology, 1995)

The overall prevalence of heart failure is 3-20 per 1000 population, although this exceeds 100 per 1000 in those aged 65 years and over. The annual incidence of heart failure is 1-5 per 1000, and the relative incidence doubles for each decade of life after the age of 45 years. The overall incidence is likely to increase in the future, because of both an ageing population and therapeutic advances in the management of acute myocardial infarction leading to improved survival in patients with impaired cardiac function.

Unfortunately, heart failure can be difficult to diagnose clinically, as many features of the condition are not organ specific, and there may be few clinical features in the early stages of the disease. Recent advances have made the early recognition of heart failure increasingly important as modern drug treatment has the potential to improve symptoms and quality of life, reduce hospital admission rates, slow the rate of disease progression, and improve survival. In addition, coronary revascularisation and heart valve surgery are now regularly performed, even in elderly patients.

A brief history

Descriptions of heart failure exist from ancient Egypt, Greece, and India, and the Romans were known to use the foxglove as medicine. Little understanding of the nature of the condition can have existed until William Harvey described the circulation in 1628. Röntgen's discovery of x rays and Einthoven's development of electrocardiography in the 1890s led to improvements in the investigation of heart failure. The advent of echocardiography, cardiac catheterisation, and nuclear medicine have since improved the diagnosis and investigation of patients with heart failure.

Blood letting and leeches were used for centuries, and William Withering published his account of the benefits of digitalis in 1785. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, heart failure associated with fluid retention was treated with Southey's tubes, which were inserted into oedematous peripheries, allowing some drainage of fluid.

A brief history of heart failure

| 1628 | William Harvey describes the circulation |

| 1785 | William Withering publishes an account of medical use of digitalis |

| 1819 | René Laennec invents the stethoscope |

| 1895 | Wilhelm Röntgen discovers x rays |

| 1920 | Organomercurial diuretics are first used |

| 1954 | Inge Edler and Hellmuth Hertz use ultrasound to image cardiac structures |

| 1958 | Thiazide diuretics are introduced |

| 1967 | Christiaan Barnard performs first human heart transplant |

| 1987 | CONSENSUS-I study shows unequivocal survival benefit of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors in severe heart failure |

| 1995 | European Society of Cardiology publishes guidelines for diagnosing heart failure |

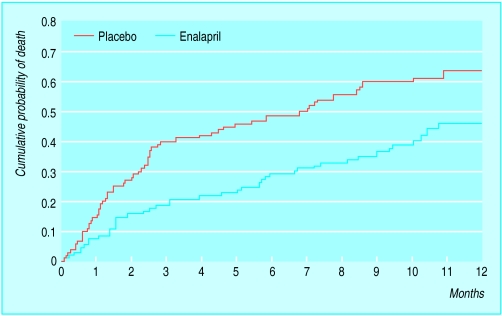

It was not until the 20th century that diuretics were developed. The early, mercurial agents, however, were associated with substantial toxicity, unlike the thiazide diuretics, which were introduced in the 1950s. Vasodilators were not widely used until the development of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors in the 1970s. The landmark CONSENSUS-I study (first cooperative north Scandinavian enalapril survival study), published in 1987, showed the unequivocal survival benefits of enalapril in patients with severe heart failure.

Epidemiology

Studies of the epidemiology of heart failure have been complicated by the lack of universal agreement on a definition of heart failure, which is primarily a clinical diagnosis. National and international comparisons have therefore been difficult, and mortality data, postmortem studies, and hospital admission rates are not easily translated into incidence and prevalence. Several different systems have been used in large population studies, with the use of scores for clinical features determined from history and examination, and in most cases chest radiography, to define heart failure.

The Framingham heart study has been the most important longitudinal source of data on the epidemiology of heart failure

Contemporary studies of the epidemiology of heart failure in United Kingdom

| Study | Diagnostic criteria |

|---|---|

| Hillingdon heart failure study (west London) | Clinical (for example, shortness of breath, effort intolerance, fluid retention), radiographic, and echocardiographic |

| ECHOES study (West Midlands) | Clinical and echocardiographic (ejection fraction <40%) |

| MONICA population (north Glasgow) | Clinical and echocardiographic (ejection fraction ⩽30%) |

The Task Force on Heart Failure of the European Society of Cardiology has recently published guidelines on the diagnosis of heart failure, which require the presence of symptoms and objective evidence of cardiac dysfunction. Reversibility of symptoms on appropriate treatment is also desirable. Echocardiography is recommended as the most practicable way of assessing cardiac function, and this investigation has been used in more recent studies.

In the Framingham heart study a cohort of 5209 subjects has been assessed biennially since 1948, with a further cohort (their offspring) added in 1971. This uniquely large dataset has been used to determine the incidence and prevalence of heart failure, defined with consistent clinical and radiographic criteria.

Several recent British studies of the epidemiology of heart failure and left ventricular dysfunction have been conducted, including a study of the incidence of heart failure in one west London district (Hillingdon heart failure study) and large prevalence studies in Glasgow (north Glasgow MONICA study) and the West Midlands ECHOES (echocardiographic heart of England screening) study. It is important to note that epidemiological studies of heart failure have used different levels of ejection fraction to define systolic dysfunction. The Glasgow study, for example, used an ejection fraction of 30% as their criteria, whereas most other epidemiological surveys have used levels of 40-45%. Indeed, prevalence of heart failure seems similar in many different surveys, despite variation in the levels of ejection fraction, and this observation is not entirely explained.

Prevalence of heart failure (per 1000 population), Framingham heart study

| Age (years) | Men | Women |

|---|---|---|

| 50-59 | 8 | 8 |

| 80-89 | 66 | 79 |

| All ages | 7.4 | 7.7 |

Prevalence of heart failure

During the 1980s the Framingham study reported the age adjusted overall prevalence of heart failure, with similar rates for men and women. Prevalence increased dramatically with increasing age, with an approximate doubling in the prevalence of heart failure with each decade of ageing.

Methods of assessing prevalence of heart failure in published studies

Clinical and radiographic assessment

Echocardiography

General practice monitoring

Drug prescription data

In Nottinghamshire, the prevalence of heart failure in 1994 was estimated from prescription data for loop diuretics and examination of the general practice notes of a sample of these patients, to determine the number who fulfilled predetermined criteria for heart failure. The overall prevalence of heart failure was estimated as 1.0% to 1.6%, rising from 0.1% in the 30-39 age range to 4.2% at 70-79 years. This method, however, may exclude individuals with mild heart failure and include patients treated with diuretics who do not have heart failure.

Incidence of heart failure

The Framingham data show an age adjusted annual incidence of heart failure of 0.14% in women and 0.23% in men. Survival in the women is generally better than in the men, leading to the same point prevalence. There is an approximate doubling in the incidence of heart failure with each decade of ageing, reaching 3% in those aged 85-94 years.

Annual incidence of heart failure (per 1000 population), Framingham heart study

| Age (years) | Men | Women |

|---|---|---|

| 50-59 | 3 | 2 |

| 80-89 | 27 | 22 |

| All ages | 2.3 | 1.4 |

The recent Hillingdon study examined the incidence of heart failure, defined on the basis of clinical and radiographic findings, with echocardiography, in a population in west London. The overall annual incidence was 0.08%, rising from 0.02% at age 45-55 years to 1.2% at age 86 years or over. About 80% of these cases were first diagnosed after acute hospital admission, with only 20% being identified in general practice and referred to a dedicated clinic.

The MONICA study is an international study conducted under the auspices of the World Health Organisation to monitor trends in and determinants of mortality from cardiovascular disease

Prevalence (%) of left ventricular dysfunction, north Glasgow (MONICA survey)

| Age group (years) | Asymptomatic | Symptomatic | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | Men | Women | ||

| 45-54 | 4.4 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 1.2 | |

| 55-64 | 3.2 | 0.0 | 2.5 | 2.0 | |

| 65-74 | 3.2 | 1.3 | 3.2 | 3.6 | |

The Glasgow group of the MONICA study and the ECHOES Group have found that coronary artery disease is the most powerful risk factor for impaired left ventricular function, either alone or in combination with hypertension. In these studies hypertension alone did not appear to contribute substantially to impairment of left ventricular systolic contraction, although the Framingham study did report a more substantial contribution from hypertension. This apparent difference between the studies may reflect improvements in the treatment of hypertension and the fact that some patients with hypertension, but without coronary artery disease, may develop heart failure as a result of diastolic dysfunction.

Prevalence of left ventricular dysfunction

Large surveys have been carried out in Britain in the 1990s, in Glasgow and the West Midlands, using echocardiography.

In Glasgow the prevalence of significantly impaired left ventricular contraction in subjects aged 25-74 years was 2.9%; in the West Midlands, the prevalence was 1.8% in subjects aged 45 and older.

The higher rates in the Scottish study may reflect the high prevalence of ischaemic heart disease, the main precursor of impaired left ventricular function in both studies. The numbers of symptomatic and asymptomatic cases, in both studies, were about the same.

Ethnic differences

Ethnic differences in the incidence of and mortality from heart failure have also been reported. In the United States, African-American men have been reported as having a 33% greater risk of being admitted to hospital for heart failure than white men; the risk for black women was 50%.

In the United States mortality from heart failure at age <65 years has been reported as being up to 2.5-fold higher in black patients than in white patients

Cost of heart failure

| Country | Cost | % Healthcare costs | % Of costs due to admissions |

|---|---|---|---|

| UK, 1990-1 | £360m | 1.2 | 60 |

| US, 1989 | $9bn | 1.5 | 71 |

| France, 1990 | FF11.4bn | 1.9 | 64 |

| New Zealand, 1990 | $NZ73m | 1.5 | 68 |

| Sweden, 1996 | Kr2.6m | 2.0 | 75 |

A similar picture emerged in a survey of heart failure among acute medical admissions to a city centre teaching hospital in Birmingham. The commonest underlying aetiological factors were coronary heart disease in white patients, hypertension in black Afro-Caribbean patients, and coronary heart disease and diabetes in Indo-Asians. Some of these racial differences may be related to the higher prevalence of hypertension and diabetes in black people and coronary artery disease and diabetes mellitus in Indo-Asians.

Impact on health services

Heart failure accounts for at least 5% of admissions to general medical and geriatric wards in British hospitals, and admission rates for heart failure in various European countries (Sweden, Netherlands, and Scotland) and in the United States have doubled in the past 10-15 years. Furthermore, heart failure accounts for over 1% of the total healthcare expenditure in the United Kingdom, and most of these costs are related to hospital admissions. The cost of heart failure is increasing, with an estimated UK expenditure in 1996 of £465m (£556m when the costs of community health services and nursing homes are included).

Key references

Clarke KW, Gray D, Hampton JR. Evidence of inadequate investigation and treatment of patients with heart failure. Br Heart J 1994;71:584-7.

Cowie MR, Mosterd A, Wood DA, Deckers JW, Poole-Wilson PA, Sutton GC, et al. The epidemiology of heart failure. Eur Heart J 1997;18:208-25.

Cowie MR, Wood DA, Coats AJS, Thompson SG, Poole-Wilson PA, Suresh V, et al. Incidence and aetiology of heart failure: a population-based study. Eur Heart J 1999;20:421-8.

Dries DL, Exner DV, Gersh BJ, Cooper HA, Carson PE, Domanski MJ. Racial differences in the outcome of left ventricular dysfunction. N Engl J Med 1999;340:609-16.

Ho KK, Pinsky JL, Kannel WB, Levy D. The epidemiology of heart failure: the Framingham study. J Am Coll Cardiol 1993;22:6-13A.

Lip GYH, Zarifis J, Beevers DG. Acute admissions with heart failure to a district general hospital serving a multiracial population. Int J Clin Pract 1997;51:223-7.

McDonagh TA, Morrison CE, Lawrence A, Ford I, Tunstall-Pedoe H, McMurray JJV, et al. Symptomatic and asymptomatic left-ventricular systolic dysfunction in an urban population. Lancet 1997;350:829-33.

The Task Force on Heart Failure of the European Society of Cardiology. Guidelines for the diagnosis of heart failure. Eur Heart J 1995;16:741-51.

Hospital readmissions and general practice consultations often occur soon after the diagnosis of heart failure. In elderly patients with heart failure, readmission rates range from 29-47% within 3 to 6 months of the initial hospital discharge. Treating patients with heart failure with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors can reduce the overall cost of treatment (because of reduced hospital admissions) despite increased drug expenditure and improved long term survival.

R C Davis is clinical research fellow and F D R Hobbs is professor in the department of primary care and general practice, University of Birmingham.

Figure.

The foxglove was used as a medicine in heart disease as long ago as Roman times

Figure.

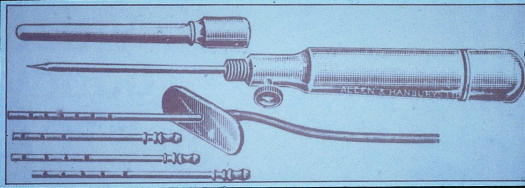

Southey's tubes were at one time used for removing fluid from oedematous peripheries in patients with heart failure

Figure.

In 1785 William Withering of Birmingham published an account of medicinal use of digitalis

Figure.

Mortality curves from the CONSENSUS-I study

Acknowledgments

The pictures of William Withering and of the foxglove are reproduced with permission from the Fine Art Photographic Library. The box of definitions of heart failure is adapted from Poole-Wilson PA et al, eds (Heart failure. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1997:270). The table showing the prevalence of left ventricular dysfunction in north Glasgow is reproduced with permission from McDonagh TA et al (see key references box). The table showing costs of heart failure is adapted from McMurray J et al (Br J Med Econ 1993;6:99-110).

Footnotes

The ABC of heart failure is edited by C R Gibbs, M K Davies, and G Y H Lip. CRG is research fellow and GYHL is consultant cardiologist and reader in medicine in the university department of medicine and the department of cardiology, City Hospital, Birmingham; MKD is consultant cardiologist in the department of cardiology, Selly Oak Hospital, Birmingham. The series will be published as a book in the spring.