Tobacco litigation has transformed the prospects for tobacco control, first in the United States and more recently worldwide. It has forced tobacco companies to sit at the bargaining table with tobacco control advocates, has produced settlements under which the industry is committed to paying about $10bn each year to reimburse American states for healthcare expenditure caused by tobacco, and it has generally put the industry on the political defensive. For example, the millions of pages of internal documents from the tobacco industry that are now open for public inspection in Minneapolis, Minnesota, and in Guildford, England, as a result of the Minnesota state litigation continue to fuel exposés of industry misconduct, and only a fraction of the material has yet been analysed.

This article describes tobacco litigation in the United States and reviews developments elsewhere. It concludes with the bleak picture in Great Britain.

Summary points

Tobacco litigation is transforming the prospects for tobacco control worldwide

Litigation in the United States is moving forward on several fronts, including individual cases, class actions, third party reimbursement actions, and secondhand smoke cases

Other countries have followed suit, with governmental actions in courts both in the United States and locally and with private individual, class action, and reimbursement cases

Australia has seen a major ruling on the dangers of environmental tobacco smoke, and there is currently a viable smokers' class action

Britain has not been hospitable to tobacco litigation, with a recent negative judicial decision forcing a group action to be abandoned

Methods

We examined the reported judicial decisions in tobacco litigation, and we collected and analysed other legal documents in other tobacco cases.

Cases in the United States

Tobacco litigation, even in the United States, has not been easy or uniformly successful. Indeed, for the first 42 years of litigation, from 1954 to 1996, the industry maintained its proud record of never having paid a penny to its victims. It did this through litigation tactics that made the cases prohibitively expensive for plaintiffs and their attorneys. One internal memo by R J Reynolds Tobacco Company stated, “The way we won these cases, to paraphrase Gen. Patton, is not by spending all of Reynolds' money, but by making the other son of a bitch spend all of his.”1 Although the industry persistently refused to admit that smoking caused any disease, it was remarkably successful at convincing judges and juries that the smoker was entirely at fault for “choosing” to smoke in the face of known risks as well as the government mandated health warnings included on cigarette packs since 1966.

“Global settlements”

The industry's solid phalanx cracked in 1996 when Brooke Group Ltd, parent of what had once been the major player Liggett & Myers Tobacco Company, settled with several suing states. It agreed to pay monetary damages, add meaningful warnings on cigarette packages, and provide testimony about industry misconduct in pending cases against its competitors.2 The remainder of the American tobacco industry rushed to the bargaining table with the states' attorneys, class action attorneys, and one public health advocate (later, two), reaching an agreement in June 1997. The resulting “global settlement,” which ironically would have applied only within the United States, would have provided substantial money and public health concessions from the tobacco industry in return for virtual immunity from further tobacco litigation. It never obtained the requisite approval from Congress, but none the less this showed how frightened the industry was of tobacco litigation and how far it would go to put this litigation behind it.

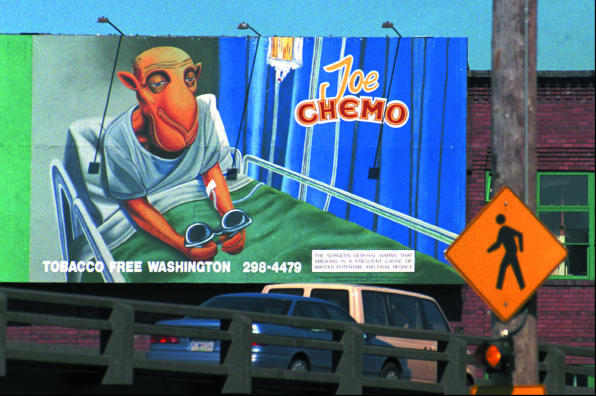

While the Congressional deliberations were pending, the industry settled with four states suing to recover their Medicaid costs for treatment of diseases attributable to smoking, with a class of non-smoking airline flight attendants suing for health injuries caused by environmental tobacco smoke, and with a “private attorney general” suing in California to end the infamous “Joe Camel” marketing campaign. After the industry turned against the “global settlement” implementation legislation, which had become much more pro-health by adding more money and public health protections and taking away the immunity from litigation, the legislation died in the US Senate. The industry then turned towards settling the remaining state Medicaid lawsuits, doing so in November 1998 for a lot of money (together with the first four settling states, about $10bn/year in perpetuity), an agreement to ban most outdoor advertising, and some other modest public health measures. Unlike the “global settlement,” the 1998 agreement with the states neither required the concurrence of Congress nor affected litigation brought by parties other than US states or their political subdivisions.

Individual cases

Litigation continues briskly in the United States. Individual cases, which had been going nowhere for more than four decades, have scored impressive wins. So far in 1999 there have been two jury verdicts against Philip Morris, assessing a total of $130m (subsequently judicially reduced to $57m) in punitive damages—amounts added to the compensatory damages to punish past wrongdoing and deter others. What moved the juries were the incriminating documents produced in the Minnesota case and elsewhere: Philip Morris made the usual “blame the smoker” arguments, but the juries concluded that far greater blame attached to the industry. In three other cases, where the plaintiffs' efforts to introduce incriminating documents were thwarted, juries continued to side with the industry.

Class actions

Class actions, in which a few named individuals sue on behalf of all others similarly situated, have also been important in the American tobacco litigation scene. Although some courts have dismissed these actions on the basis that the smokers' claims are too diverse, a case in Louisiana seeking medical monitoring for smokers3 and two class actions in Florida have been allowed to proceed. The first Florida case, on behalf on non-smoking flight attendants exposed to environmental tobacco smoke, was settled in October 1997 in exchange for a $300m fund to research the diagnosis and treatment of diseases caused by environmental tobacco smoke, as well as an agreement on procedures to simplify and facilitate future trials.4 The second case, on behalf of all Florida smokers who had diseases caused by tobacco (or their survivors), resulted in July 1999 in a jury verdict finding 20 diseases to be caused by cigarette smoking, cigarettes to be defective and unreasonably dangerous products, and all major US tobacco companies to have been guilty of negligence, fraud, fraudulent concealment, conspiracy to commit fraud and fraudulent concealment, and intentional infliction of emotional distress.5 Damages to individual smokers, as well as the amount of punitive damages to be imposed, will be assessed in subsequent proceedings.

Environmental tobacco smoke

In addition to the flight attendants' class action, there have been other successful environmental tobacco smoke cases in the United States. In October 1997 an asthmatic corrections officer who became seriously ill from breathing environmental tobacco smoke at work won $300 000 after a jury determined that the New York Department of Corrections unlawfully failed to accommodate his disability.6 The US Supreme Court recognised a prisoner's claim that being housed with a smoking cellmate constituted cruel and unusual punishment, in violation of the 8th amendment to the US constitution.7 A court has even allowed tenants to withhold rent when their landlord failed to protect them from environmental tobacco smoke seeping into their apartment from a nightclub on the premises.8

Third party reimbursement

Third party reimbursement cases, modelled on the successful state Medicaid reimbursement cases, continue to be filed. Health insurers, including Blue Cross Blue Shield plans and health and welfare funds managed by unions, have cases pending. Many Native American tribes recently sued the industry for the cost of treating the high incidence of diseases caused by tobacco among their members. And the federal government filed a lawsuit to recover the tobacco related expenses of its Medicare, veterans, and military health programmes, as well as to require the industry to change its behaviour and to disgorge profits received as a result of its violations of the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organisations Act.9 Courts have differed in their responses to these third party cases, with some opining that the payer's injury is too indirect to be compensable and others approving the cases as a direct and efficient way to make cigarette companies pay for the harm they cause. The only such case to have gone to trial, on behalf of union funds in Ohio, resulted in a jury verdict for the companies.

Cases outside the United States

Governments other than the US government have filed third party reimbursement suits in the United States. Guatemala, Venezuela, Bolivia, and Nicaragua all have cases pending in the federal district court in Washington, DC, seeking recovery of national healthcare expenses related to tobacco. Similar cases have also been filed in some other countries' own courts. A court in the Marshall Islands has permitted its government to proceed there against the international tobacco companies that supply the local market.10 The Canadian province of British Columbia has filed such a suit, as has the government health insurance body in the department of St Nizaire, France. Two private health insurers in Israel, covering the majority of Israeli citizens, have filed similar actions.

Building on the American experience, lawyers in several countries have brought individual suits against the tobacco industry. Argentina, Ireland, and Israel each have several such cases pending, and cases have also been filed in Finland, France, Japan, Norway, Sri Lanka, Thailand, and Turkey.

Australian cases

Tobacco litigation has a long history in Australia. In 1991 the Federal Court ruled that advertisements run in 1986 by the Tobacco Institute of Australia denying adverse health effects from environmental tobacco smoke violated the Trade Practices Act (1974), which prohibits misleading or deceptive conduct in trade or commerce.11 More recently, a representative proceeding (class action) against the major Australian tobacco companies was started in the Federal Court of Australia on behalf of persons who have suffered loss from smoking related disease. The lawsuit alleges liability in common law negligence as well as various claims under the Trade Practices Act (1974). In August 1999 the Federal Court refused the defendants' request to dismiss the class action proceedings and indicated that the case would be tried sometime in 2000.12 A second representative proceeding, on behalf of public health and medical organisations, was filed in the federal court in September 1999. This case seeks reimbursement of money spent on tobacco control since 1992 and judicial orders (injunctions) changing the industry's behaviour. As regards passive smoking, a claim brought in the Australian Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission under the Disability Discrimination Act (1992) was successful when it was held that the failure to provide access to a smoke free environment in a nightclub constituted unlawful discrimination in respect of a person with a disability due to asthmatic lungs. Compensation of $A2000 was awarded, and further orders are expected requiring the hotel in question to make adequate provision for access to smoke free areas for people with such a disability.13

British cases

The litigation situation in Britain has had serious setbacks. A group action by 54 people with lung cancer was killed off in March 1999 by a hostile judge who refused to exercise his discretion to allow an extension of the three year statute of limitations for 28 of the claimants and commented that the prospects of success for the remaining 16 claimants were “by no means self-evident.”14 Furthermore, potential claims by health authorities have faced political opposition from the Department of Health, and passive smoking cases have yet to succeed. The only silver lining is the success of workplace passive smoking actions at employment tribunals by non-smokers who have been forced to leave their jobs. The Legal Aid Board has refused to support tobacco litigation, which means that lawyers must proceed on a “no win, no fee” basis, taking a commercial view of the risk and likely rewards. If a tobacco company wins, the plaintiffs' lawyers lose the value of thousands of hours of time and out of pocket expenses, but the afflicted smokers are responsible for the defendants' costs and face bankruptcy. (In the United States, the unsuccessful plaintiff does not have to pay the defendants' costs and does not therefore face such a severe disincentive to take legal action.) Indeed, in response to the industry's threat to bankrupt his clients, the experienced and dedicated solicitor for a group of smokers was forced to agree not to bring any more cases against any part of the tobacco industry for the next five years and against the defendants, Imperial Tobacco and Gallaher, for the next 10 years, once it became apparent that the trial judge was inclined to accept the defendants' arguments.

As well as severe “down side” risks, the “up side” is not as attractive in the United Kingdom as in the United States. In Britain there are not the prospects of very large punitive damages against tobacco companies if the action is successful. Individual US smokers have seen awards of tens of millions of dollars, but the outlook for a successful case in Britain would be around £100 000 ($160 000). The lengthy procedural battles will drain the resources of all but the wealthiest plaintiffs' lawyers, and the risk of failure and low level of potential reward make such actions very risky in the British courts. In contrast to the United States, in the United Kingdom there is no cadre of super-rich personal injury lawyers with the deep pockets to face the unfavourable economics and risks of tobacco litigation.

In Britain, the blame the smoker argument still holds great sway. It is widely assumed that the warnings and the high level of awareness of the dangers somehow absolve the tobacco companies of their responsibilities. As a result, the conduct of the tobacco companies since 1950 has not been examined in detail under oath in court. The decisive success of the US lawyers in exposing thousands of incriminating tobacco company documents and concentrating on arguments of addiction and the targeting of children has yet to be repeated in Britain, even though many of these documents reveal unethical (if not criminal) behaviour by British tobacco companies.

In Britain, however, a legislative and policy approach is achieving results. Taxes raised on tobacco in the United Kingdom exceed the value per smoker of the US master settlement agreement between the industry and the states by a factor of eight—with no payments to lawyers or risk of failure in court. Tobacco advertising is to be comprehensively banned, and existing health and safety legislation will be deployed to reduce passive smoking in the workplace. A white paper, Smoking Kills, sets out a comprehensive package of measures to tackle smoking. In the United States, such a national strategy would, without question, be blocked by Congress. Perhaps the success of litigation in the United States is a response to the failure of the legislative and executive branches of the US government to curb the excesses of the tobacco industry.

Conclusions

Thus tobacco litigation remains a productive and promising strategy in much of the world, with the unfortunate exception of Britain. Up to date information on tobacco litigation can be found at the Tobacco Control Resource Center and Tobacco Products Liability Project website (www.tobacco.neu.edu).

Figure.

ELAINE THOMPSON/AP PHOTO

“Joe Chemo” was a counterblast to the “Joe Camel” marketing campaign

Acknowledgments

We thank Edward L Sweda for information on lawsuits involving environmental tobacco smoke and for help with references.

Editorial by Davis

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Haines v Liggett Group, Inc, 818 F Supp 414, 421 (DNJ 1993).

- 2.Tobacco Products Litigation Reporter. 1996. p. 11. :3.160-3.174. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scott v American Tobacco Co, 731 So.2d 189 (Louisiana Supreme Court 1999).

- 4.Broin v Philip Morris Companies, Inc, aff'd sub. nom. Ramos v Philip Morris Companies, Inc, 1999 Fla App LEXIS 3422 (4th Dept 1999).

- 5.Engle v RJ Reynolds Tobacco Co, No. 94-08273 CA 22 (Dade County Circuit Court, Florida).

- 6.Muller v Costello, 997 F Supp 299 (NDNY 1998).

- 7.Helling v McKinney, 509 US 25 (1993).

- 8.50-58 Gainsborough Realty Trust v Haile (Massachusetts Housing Court, Boston Division, 1998) Tobacco Products Litigation Reporter. 1998;13:2. .302-2.312. [Google Scholar]

- 9.US Department of Justice v Philip Morris, Inc (US District Court, District of Columbia) Tobacco Products Litigation Reporter. 1999;4:3. .171-3.220. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Republic of the Marshall Islands v American Tobacco Co, Civil Case No 1997-261 (Marshall Islands High Court 1998) Tobacco Products Litigation Reporter. 1998;13:2. .501-2.522. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Australian Federation of Consumer Organizations Inc v The Tobacco Institute of Australia Ltd (Federal Court, NSW District) Tobacco Products Litigation Reporter. 1991;6:2. .77-2.293. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nixon v Philip Morris (Australia) Ltd [1999] FCA 1107.

- 13.Meeuwissen v Hilton Hotels of Australia Pty Ltd, Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission, H97/51, 25 September 1997.

- 14.Hodgson v Imperial Tobacco Ltd, Order of Justice Wright, 5 March 1999 (High Court).