Abstract

Monoclonal antibodies prepared against recombinant Vif derived from the 34TF10 strain of feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) were used to assess the expression and localization of Vif in virus-infected cells. Analyses by Western blotting and by immunoprecipitation from cells infected with FIV-34TF10 revealed the presence of a single 29-kDa species specific for virus-infected cells. Confirmation of antibody specificity was also performed by specific immunoprecipitation of in vitro-transcribed and -translated recombinant Vif. Localization experiments were also performed on virus-infected cells, using different fixation procedures. Results for methanol fixation protocols similar to those reported for localization of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) Vif showed a predominant cytoplasmic localization for FIV Vif, very similar to localization of HIV type 1 Vif and virtually identical to the localization observed for the Gag antigens of the virus. However, with milder fixation procedures that used 2% formaldehyde at 4°C, FIV Vif was strongly evident in the nucleus. The localization was distinct from the nuclear localization noted with Rev and did not involve the nucleolus. Attempts to show colocalization or coprecipitation of Vif with Gag antigens were unsuccessful. In addition, Vif was not detected in purified FIV virions. The results are consistent with the notion that the primary role of Vif in virus infection initiates in the nucleus.

Vif (viral infectivity factor) is an accessory protein encoded by all lentiviruses except equine infectious anemia virus (32). Mutagenesis studies of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) Vif have revealed that the expression of this gene product is critical for generation of infectious HIV-1 progenitor virus from certain nonpermissive cell types but not from other permissive ones (10, 11, 13, 38, 48, 52).

The vif gene of both HIV-1 and feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) resides 3′ of the pol gene in the viral genome, and the product is translated from a unique spliced RNA (35, 50). However, comparison of the linear sequence of HIV-1 and FIV Vif proteins reveals only a vestige of relatedness at the amino acid level, the two proteins sharing only the conserved (S/T)LQ(F/Y/R)LA motif also shared by Vifs of other lentiviruses (31, 32). Mutagenesis of this motif in both HIV-1 (54) and FIV (42) results in inactivation of the phenotype.

Although Vif has been extensively studied since it was first recognized as a gene product encoded by HIV-1, its precise role in the virus life cycle remains to be understood. Vif positively modulates infection such that virus produced in the absence of a functional Vif is able to bind and penetrate susceptible T cells but is limited in its ability to cause productive viremia (45, 48, 52). It has also been proposed that the defect in Vif-deficient infections may relate to postentry instability of viral nucleoprotein complex (45). Presence of Vif in target cells challenged with Vif-deficient virus is not sufficient for the rescue of productive virus (13, 52), leading to the hypothesis that this protein functions in the late stages of the viral life cycle to confer infectivity on progeny virus. This would indicate that Vif is important for one or more of the stages involving assembly, budding, maturation, or a combination of these steps. Vif-deficient virus replicates in certain cells such as SupT1 (3, 37) and C8166 (17, 45, 48) but not in others such as primary peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) (5, 10, 11) and the H-9 T-cell line (2, 3, 10, 45, 48). Furthermore, the kinetics of infection by Vif HIV-1 is substantially delayed in Jurkat cells (20). These findings point to the involvement of host cell factors that can substitute for Vif function (44, 46, 47, 51). Heterokaryons generated by the fusion of permissive and nonpermissive cells bear the latter phenotype, suggesting that nonpermissive cells harbor a suppressor of viral infectivity that Vif helps to overcome (44).

FIV Vif has also been studied, although not to the degree of the primate lentivirus Vifs. Studies have shown that a Vif-negative mutant of FIV-TM2 produced in Crandell feline kidney (CrFK) cells could not productively infect the primary T-cell line Mya 1 (50). The mutant virus could, however, be transmitted by cocultivation of Mya-1 cells with CrFK transfected with the mutant proviral clone. It was also shown by Shacklett and Luciw (42) that mutations in Vif of FIV-34TF10 resulted in production of a markedly lowered level of cell-free virus and viral protein in CrFK cells. These authors went on to analyze the effect of the mutations within the vif gene on cell growth and concluded that several regions analyzed were critical for the replication of FIV-34TF10 in CrFK and G355-5 glial cells. The single conserved motif, (S/T)LQ(F/Y/R)LA in all primate and nonprimate lentivirus Vifs, is critical for biological function (54). These findings parallel the results seen with the primate Vifs, in spite of the observed primary structure differences, implying a similar role for the Vifs of human and feline lentiviruses. However, cells that complement a Vif defect have not been defined for the feline system.

Studies to localize HIV-1 Vif have indicated that the primate lentivirus protein is primarily localized in the cytoplasm (14, 15). It has been reported that Vif is associated with Gag and becomes part of the virus particle (2, 4, 12, 23, 30). Recent studies, however, have suggested that the level seen in mature virus particles is no more than would be expected from contamination with cellular proteins (6). Additionally, it has been shown that the extent of Vif incorporation into virions depends on cellular expression levels and is nonspecific (46). Overall, the findings are more consistent for a cellular role for Vif.

In the present study, we have prepared monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) to FIV Vif and have attempted to localize the protein in infected feline cells. The results yielded the surprising finding that FIV Vif, under mild fixation procedures, localizes to the nucleus of the infected cell. This observation indicates that the primary role of Vif must involve functions initially orchestrated in the nucleus but does not appear to involve the nucleolar complex.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and virus.

Adherent glial cells (G355-5; a kind gift from Don Blair) were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Gemini Bioproducts, Calabasas, Calif.), 2 mM l-glutamine (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.), 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Sigma), 10 mM HEPES buffer (Sigma), 1× nonessential amino acids (Sigma), 1× β-mercaptoethanol (Gibco-BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.), and 50 μg of gentamicin (Gemini Bioproducts). The molecular clone FIV-34TF10 (49), derived from the FIV-Petaluma isolate (33), was used in all studies described below. Additionally, we used a variant of FIV-PPR, a molecular clone derived from the San Diego isolate (35); this clone, termed FIV-PPRchim42, has the ability to infect G355-5 cells but is otherwise identical to FIV-PPR (28). Importantly, this clone has the same Vif sequence as does FIV-PPR and served as a convenient control for FIV-34TF10 in the identical host background. Culture supernatants from FIV-34TF10-, FIV-PPRchim42-infected, or mock-infected cells were assayed for reverse transcriptase (RT) activity and then used for preparation of gradient purified FIV as described previously (9).

Preparation and screening of Vif MAbs.

Fourteen-week-old female BALB/c mice were immunized intraperitoneally with 30.0, 45.0, and 60.0 μg of recombinant Vif at days 0, 21, and 42, respectively. Recombinant Vif injected at days 0 and 21 was mixed with adjuvant (Ribi MPL + TDM emulsion, used as instructed by the manufacturer [Ribi Immunochem, Hamilton, Mont.]). The immunization at day 42 employed no adjuvant. On day 45, mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation; spleens and mesenteric lymph nodes were dissected out and then disrupted by passage through a fine wire mesh screen. The washed, immune, lymphoid cell population was fused with X-63 Sc2 cells (a proprietary multiply cloned mouse hybridoma cell line derived originally from the NS-1 hybridoma cell line). For fusion, polyethylene glycol 1500 was obtained from Boehringer GmbH, Mannheim, Germany. Emerging hybridomas were cultured in 96-well plates (product no. 3072; Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, N.J.) in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with hypoxanthine-aminopterin-thymidine (HAT) plus Origen (Igen International, Inc., Gaithersburg, Md.). Culture plates were fed every second day by replacing approximately 50% of the volume with fresh growth medium.

Emerging hybridoma supernatants were screened by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) against recombinant Vif (plated at 0.2 μg/well) on day 11 postfusion, and the cells plus supernatants from all wells giving >5-fold background were expanded to 24-well plates (Becton Dickinson product no. 3047) in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with HAT plus Origen. Putative Vif-specific hybridoma supernatants were then rescreened by ELISA against recombinant Vif and also against three other unrelated FIV recombinant proteins also derived from Escherichia coli. Hybridomas producing anti-Vif antibody were then cloned by limiting dilution in 96-well plates using RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with HAT plus Origen.

Emerging cloned hybridoma supernatants were rescreened by ELISA against recombinant E. coli-derived Vif antigen (plus unrelated E. coli-derived recombinant FIV gene products). Putative Vif-specific hybridoma supernatants were then checked by Western blotting against recombinant Vif antigen, and hybridomas producing anti-Vif MAbs were frozen down to LN2 storage; they were also expanded in cell culture for MAb isolation utilizing Staphylococcus aureus protein A (SpA) columns (16).

Preparation of recombinant Vif.

For expressing the recombinant protein in E. coli, we modified the pUC112 vector (a kind gift of Steve Hughes, National Cancer Institute) to include a six-histidine tag at the N terminus of the coding sequence, to facilitate nickel column chromatography of expressed proteins. The original NdeI site was destroyed by oligonucleotide-directed mutagenesis, coding sequences for methionine and six histidines were added, and a new NdeI site was generated at the 3′ end of this insert. This generated a convenient cloning site, with the first half of NdeI (CAT↓ATG) coding for the sixth histidine residue and the second half coding for the first methionine of the cloned gene. This His-tagged vector, pUC112Nhis, allowed for an easy one-step purification based on Ni affinity chromatography (36) on an Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid column (Qiagen Inc., Chatsworth, Calif.) (18, 19, 27). The gene corresponding to Vif from FIV-34TF10 was cloned between the NdeI site and a downstream EcoRI site of the above vector and checked on both strands by dideoxy sequencing (40). The protein was purified to homogeneity by Ni affinity chromatography (21) after purification of inclusion bodies, as described earlier (26). All the steps during purification were assessed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) as described elsewhere (39).

Synthetic oligonucleotide primers.

To amplify and clone the vif gene from FIV-34TF10 into a eukaryotic expression vector, the primers 5′34Vif (5′-CCCTGCGCTCTTCCTGAATTCGATGAGTGA-3′) and 3′-34Vif (5′-GAATAATACTATTATTTCCTCGAGTCATAG) were synthesized and used in PCR (conditions noted below) for amplification of vif. The EcoRI and XbaI restriction sites (italicized) were then used to clone the PCR product after digestion with these enzymes into the pCR3 vector (Invitrogen, La Jolla, Calif.), using standard protocols (39).

PCR.

PCRs were carried out in 100 μl containing 200 μM deoxynucleoside triphosphates (Promega), 1× KlenTaq PCR buffer (Clontech, Palo Alto, Calif.), 100 ng of template DNA, 700 ng of each of the 5′ and 3′ primers, and 0.5× KlenTaq polymerase mix (Clontech). Reactions were carried out in a Perkin-Elmer Cetus thermocycler with 5-min presoak at 94°C, followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 15 s, 58°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 60 s, with a final 10-min soak at 72°C.

Cloning and sequencing of amplified DNA.

The PCR-amplified product was purified using the Wizard PCR preps DNA purification system (Promega, Madison, Wis.), either directly or after purification on a gel, and cloned into the pCR3 vector (Invitrogen) under control of the eukaryotic cytomegalovirus and bacterial T7 promoters. Sequencing was done by the dideoxy-chain termination method (40) using a Sequenase version 2.0 kit (Amersham Life Sciences, Cleveland, Ohio) as recommended by the manufacturer. The Vif expression clone is referred to hereafter as pCR3vif34. We also used the expression construct pCR3gag (a kind gift of Aymeric de Parseval), where the gag gene from FIV-PPR was cloned under control of the T7 promoter of the pCR3 vector as a control in the cross-linking studies detailed below.

In vitro transcription-translation and immunoprecipitation.

All clones under the T7 promoter were tested for the ability to express in a coupled transcription-translation (TnT) reaction in rabbit reticulocytes (Promega) in vitro. The lysate was assayed for the correctly translated Vif by analysis on a 10 to 20% Tricine SDS-polyacrylamide gel (Novex) followed by gel drying and autoradiography; 20 μl of the in vitro-translated product was also simultaneously analyzed by immunoprecipitation. In brief, the lysate was precleared with goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (Sigma) coupled to agarose followed by another preclearing with protein A–Tris-Acryl (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.). Two micrograms of the Vif-specific MAb, Vif1-3, was used per immunoprecipitation for 2 h at room temperature followed by a 2-h incubation with protein A–Tris-Acryl. Immunoprecipitates were washed extensively with LiCl–NP-40 and then analyzed on a 10 to 20% tricine SDS-polyacrylamide gel that was autoradiographed as above.

Immunocytochemistry.

To localize the Vif product within the cells, we tried both organic solvent-based cell fixing and prior fixing with a protein cross-linking reagent, followed by detergent permeabilization. In brief, adherent G355-5 cells transfected with FIV-34TF10 or mock transfected were cultured on four- or eight-chambered glass slides (Nalge Nunc, Naperville, Ill.) and then assayed for infectivity by RT assay as previously described (29). Cells were fixed by dipping in methanol at −20°C for 3 min (43) and then immunostained. As an alternate method, the cells were fixed for 5 min at 4°C in a 2% formaldehyde solution in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then permeabilized for 15 min in 0.2% Triton X-100 with gentle rocking. For both procedures, the cells were blocked for nonspecific reactivity by placing the slides in a freshly made solution of 1% bovine serum albumin in PBS for 1 h. Cells were incubated in a 1:100 dilution of the primary antibody for 1 h, followed by a 30-min wash in PBS with gentle rocking. Anti-mouse antibody conjugated to fluorescein isothiocyanate was used as the secondary reagent at a dilution of 1:200 in 1% bovine serum albumin for 1 h. Cells were visualized by fluorescence microscopy on a Zeiss Axioscope at ×25 magnification.

Cross-linking.

To identify the factor(s) interacting with Vif in vitro, we used a number of homobifunctional cross-linkers. The methodology, as well as results for only the dimethyl pimelidate (DMP; Pierce) cross-linking, is included here. Vif and Gag were expressed in vitro from the T7 promoter of pCR3vif34 and pCR3gag, respectively, in a coupled transcription-translation system (Promega). Cross-linking reactions were carried out in 0.1 M N-ethyl morpholinoacetic acid (pH 8.5) using 1 mM DMP for 30 min at 26°C. Reactions were terminated by adding sample buffer, and the reaction products were analyzed by 10 to 20% Tricine SDS-PAGE. Gels were dried and exposed to an X-ray film to analyze the radioactive signals.

Protease digestion of in vitro-expressed Gag was carried out using bacterially expressed and biologically active FIV protease (a generous gift from Y.-C. Lin). The protease reaction was carried out at 37°C in 0.1 M NaH2PO4–0.1 M sodium citrate–0.2 M NaCl–0.1 mM dithiothreitol–5% glycerol–5% dimethyl sulfoxide. Digested products were cross-linked with DMP as described above.

Preparation of nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts.

To determine the distribution of Vif in cells, we made nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts from both uninfected and FIV-infected cells according to well-established protocols (7, 8). We started with 109 G355-5 cells either mock infected or chronically infected with FIV-34TF10 or FIV-PPRchim42 as determined by RT assays. We normalized the salt concentration during the nuclear extraction step as suggested elsewhere (1) in order to be able to reproduce the results. For Western blot analysis, 250 μg of each lysate was loaded on a denaturing 10 to 20% Tricine SDS-polyacrylamide gel as described earlier. We also carried out Western blot analysis with a MAb to the human TATA-binding protein as a marker for nuclear proteins. As expected, the results showed the intended enrichment of this protein in the nuclear but not the cytoplasmic extract (data not shown).

RESULTS

FIV Vif is detectable in cells infected with FIV-34TF10.

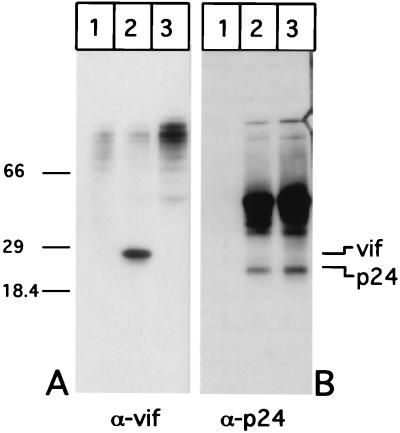

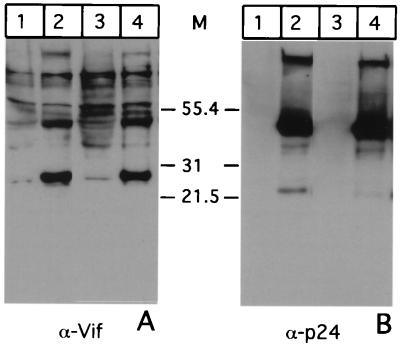

To characterize the expression and cellular localization of Vif in infected cells, we generated a panel of MAbs to bacterially expressed and affinity purified Vif from FIV-34TF10 (see Materials and Methods). The purified protein was used to generate a panel of MAbs that were screened by Western blotting for the ability to react with the 29-kDa band in FIV-34TF10-infected (Fig. 1A, lane 2) but not uninfected G355-5 glial cells (lane 1). Cell lysate from cells infected with the PPRchim42 strain, a variant of FIV-PPR that is able to grow on glial cells (28), is not recognized by MAb Vif1-3, however, due to differences in Vif sequence between the two strains. The same blots were subsequently stripped and analyzed for the p24 capsid protein using the PAK-3-2C1 MAb (Fig. 1B). The presence of equivalent amounts of the capsid protein in both 34TF10- and PPRchim42-infected cell lysates (lanes 2 and 3, respectively) indicates that the 29-kDa reactive species in the lane corresponding to 34TF10 is not an artifact generated by the infection process. Cell lysates from uninfected cells did not react (lane 1) to the anti-p24 MAb as expected.

FIG. 1.

Vif in cell lysates. Equal amounts of lysates from G355-5 cells mock infected (lane 1) and infected with FIV-34TF10 (lane 2) or FIV-PPRchim42 (lane 3) were resolved in duplicate by 10 to 20% Tricine SDS-PAGE and Western transferred. Half of the sample was incubated with MAb Vif1-3 (A), and the other half was incubated with PAK-3-2C1 (B). Positions (in kilodaltons) of molecular weight markers are shown at the left.

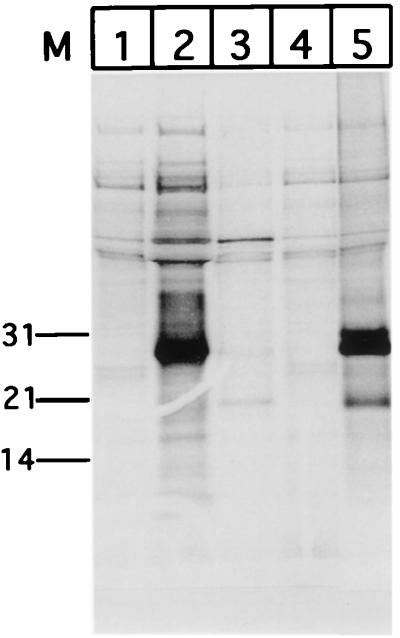

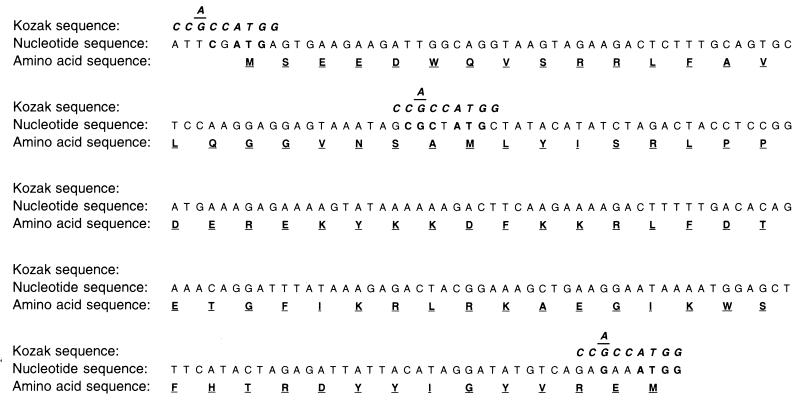

To rule out the possibility that the 29-kDa band in cells infected with 34TF10 seen to react with MAb Vif1-3 is a nonspecific artifact, we tested this antibody against Vif expressed in vitro under control of the T7 promoter of the pCR3 vector (Invitrogen). The vif gene from the 34TF10 isolate was PCR amplified, cloned under control of the T7 promoter in pCR3, and verified by sequencing. The gene was transcribed and translated in vitro, and the ability of Vif1-3 to immunoprecipitate the Vif protein from the translation mix was determined. Autoradiography of the immunoprecipitate resolved by 10 to 20% Tricine SDS-PAGE indicated the presence of a 35S-labeled product of 29 kDa (Fig. 2, lane 5), the size expected for the Vif product in vitro. The same antibody was not able to immunoprecipitate any detectable product from identical reactions with the pCR3 vector template (lane 1), pT7luc (a vector expressing the firefly luciferase from the T7 promoter; Promega) (lane 3), or the lysate without any input template (lane 4). We expressed Rev from the same vector and immunoprecipitated it with the anti-Rev polyclonal serum (Fig. 2, lane 2) as a positive control. In addition to the 29-kDa band, we were able to pick up bands corresponding to approximately 27 and 20 kDa in the in vitro reactions immunoprecipitated with MAb Vif1-3 (Fig. 2, lane 5). We attribute these extra products to translation initiation from the methionines at positions 24 and 80 relative to the first Met (Fig. 3). The band most intense in these reactions corresponded to the Vif product starting with the second methionine, which may reflect a better Kozak sequence around the second methionine than around the first (Fig. 3). Computational analysis of the DNA sequence at this position (Fig. 3) confirms that six out of nine bases match the perfect Kozak sequence (CC[A/G]CCATGG) (24, 25) around the second methionine, as opposed to four of nine in case of the first methionine. The third Met has a five-residue match, which probably explains why a truncated product from this sequence is also generated. Importantly, the results indicate the epitope that is recognized by Vif1-3 lies downstream of the third methionine. A probable site for this could be residues 83 to 94 or 242 to 250, regions that vary significantly between the 34TF10 and PPRchim42 strains of FIV, which would explain why MAb Vif1-3 is selective in its recognition of Vif from the former.

FIG. 2.

Reactivity of in vitro-expressed Vif to MAb Vif1-3. Vif was expressed in vitro from the T7 promoter in a coupled transcription-translation system (Promega). 35S-labeled proteins were immunoprecipitated with Vif1-3 and resolved by SDS-PAGE (10 to 20% gel) (lane 5). Similar reactions with the T7 vector alone (lane 1), pT7luc (lane 3), and lysate only (lane 4) were similarly immunoprecipitated with Vif1-3. Rev expressed from the same vector and immunoprecipitated with an anti-Rev polyclonal serum (lane 2) served as a positive control. Positions (in kilodaltons) of weight markers (M) are indicated at the left.

FIG. 3.

Translation initiation context sequences around the first, second, and third methionines of Vif from FIV-34TF10.

The Vif protein is not present in virus.

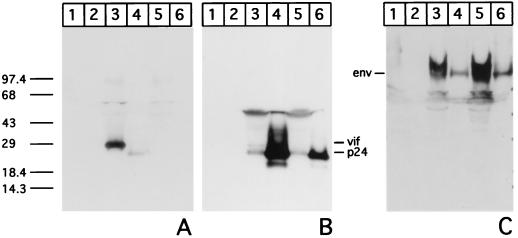

Evidence has been presented that HIV-1 Vif is associated with the virus core (23, 30). We examined this possibility with FIV, using both gradient-purified virus (data not shown) as well as preparations of the virus pelleted by ultracentrifugation from culture supernatants. The latter material was used, since virus surface-associated proteins are sometimes lost or disrupted during gradient purification procedures (D. Lerner and J. H. Elder, unpublished observation) and not detected in Western blot analysis. Equivalent amounts of RT activity for each of the two strains of FIV (mentioned earlier) from culture supernatants and a volume of supernatant from the mock-infected cells equaling that used for 34TF10 were pelleted by ultracentrifugation. The pellets were resolved by SDS-PAGE (10 to 20% gel), and Western blot analysis with Vif1-3 was carried out using the extremely sensitive Super Signal West Dura chemiluminescent assay (Pierce). We were unable to detect the Vif protein in the virus preparations (Fig. 4A, lanes 4 and 6) or from similarly treated mock-infected cells (lane 2). Cell lysates from the same cultures that were used for pelleting the virus from culture supernatants were run alongside (lanes 1, 3, and 5) for simultaneous analysis. The same blots, when stripped of MAb Vif1-3 and reacted with the anti-p24 MAb PAK-3-2C1, showed capsid protein and Gag precursor polyprotein (65 kDa) as the major reactive species in both cell lysates (Fig. 4B, lanes 3 and 5). Capsid protein was the predominant species in ultracentrifuged virus from culture supernatants (lanes 4 and 6) but not from mock-infected cells or culture supernatants therefrom (lanes 1 and 2).

FIG. 4.

Vif in cells and virus. Equal amounts of protein from mock-, FIV-34TF10-, and FIV-PPRchim42-infected cells (lanes 1, 3, and 5, respectively) and RT equivalents of ultracentrifuged FIV-34TF10 and FIV-PPRchim42 (lanes 4 and 6, respectively) or volume equivalent of the culture supernatant from mock-infected cells (lane 2) was resolved by 10 to 20% Tricine SDS-PAGE and Western transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Reactivities of the transferred proteins to MAb Vif1-3 (A) and, after complete stripping, to PAK-3-2C1 (B) were tested. The same proteins were also analyzed in a replicate set by Western blotting against the anti-surface protein polyclonal serum (C) to rule out the possible loss of proteins on the surface of the virus.

A replicate of the same Western blot was incubated with a rabbit polyclonal serum to a synthetic peptide directed to the surface region of the envelope protein (Fig. 4C). A reactive species at about 100 kDa was observed in lysates from 34TF10- and PPRchim42-infected cells (Fig. 4C, lanes 3 and 5) or corresponding virus from culture supernatants (lanes 4 and 6). Control cell lysates (Fig. 4, all panels, lanes 1) or ultracentrifuged control culture supernatant pellet (lanes 2) did not react. The reactivity to anti-surface protein polyclonal serum served as a control to confirm the presence of viral surface proteins during the ultracentrifugation of virus-containing culture supernatants.

FIV Vif localizes to the nucleus.

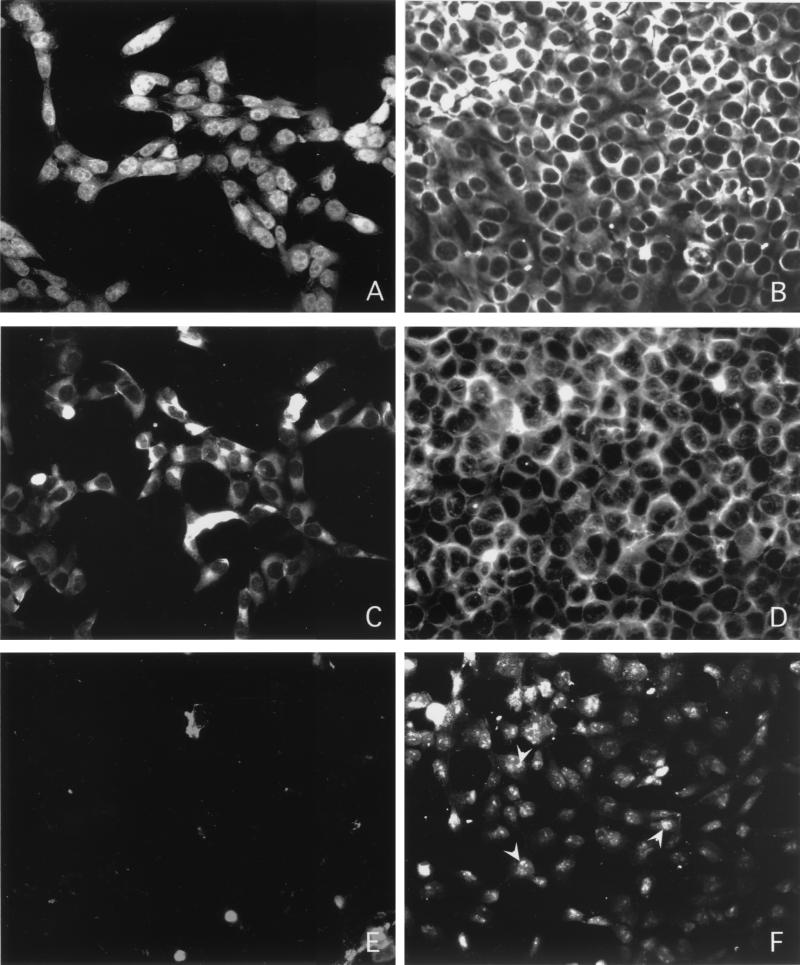

Earlier studies reported the presence of the FIV Vif protein in the cytoplasm (42, 43). In addition to reporting a cytoplasmic distribution of the FIV Vif in G355-5 cells, Simon et al. also reported that the staining did not appear to be excluded from the nucleus (43). These reports were, however, based on a polyclonal serum to a synthetic peptide corresponding to amino acids 192 to 205 (42) or to purified recombinant protein that carried the terminal extension Met-Arg-Gly-Ser-His6-Ser (43). In the present study, we examined the localization of Vif by using MAb Vif1-3 coupled with both organic solvent-based fixation and detergent permeabilization of formaldehyde-fixed cells. The latter is a far gentler method and helps retain the natural interactions through protein-protein cross-linking. Analysis of cells infected with FIV-34TF10 and fixed using formaldehyde showed that the Vif protein was typically localized in the nucleus (Fig. 5A), as opposed to the cytoplasmic localization of the p24 capsid protein detected with PAK-3-2C1 (Fig. 5B). However, when we used methanol to fix these same cells and performed immunocytochemistry with the appropriate MAbs, both Vif and the capsid protein localized to the cytoplasm (Fig. 5C and D, respectively). Mock-infected cells showed no reactivity to either Vif1-3 (Fig. 5E) or PAK-3-2C1 (data not shown). FIV-34TF10-infected glial cells fixed with formaldehyde and permeabilized as above showed nuclear and nucleolar localization of Rev (Fig. 5F), as reported earlier (34).

FIG. 5.

Indirect immunofluorescence staining of Vif and p24 capsid protein in G355-5 cells. Cells fixed with either formaldehyde (A, B, E, and F) or methanol (C and D) were stained with anti-Vif MAb Vif1-3 (A, C, and E) or anti-p24 MAb PAK-3-2C1 (B and D). Most of the Vif was found to be localized in the nucleus when cells were fixed with formaldehyde (A) but was detected typically in the cytoplasm when methanol was used as the fixative. Uninfected cells did not stain in either the cytoplasm or the nucleus with MAb Vif1-3 (E). Infected G355-5 cells stained with a rabbit polyclonal Rev antiserum showed nuclear and nucleolar localization (F).

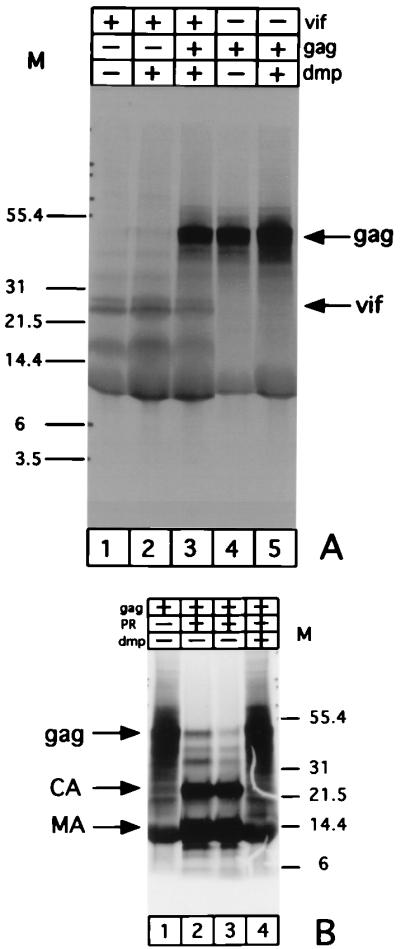

The Vif protein does not cross-link with FIV Gag precursor in vitro.

We also tested the hypothesis that the FIV Vif protein could interact with the Gag protein from the same virus in a manner suggested for HIV. The Gag and Vif proteins were transcribed and translated in vitro in separate reactions, and then equal aliquots of the reactions were mixed or treated separately with DPM cross-linking. As a control, we digested part of the same Gag polyprotein with purified FIV protease. We used the same cross-linker to check for the ability of this reagent to cross-link the protease-cleaved Gag back to the same molecular mass as uncleaved Gag when analyzed by SDS-PAGE. As shown in Fig. 6A, the Gag polyprotein and Vif do not migrate as a single species corresponding to the cumulative mass of both proteins, and only the individual Gag and Vif proteins are observed. The protease-digested Gag, on the other hand, migrated as a single species corresponding to the mass of the polyprotein (Fig. 6B).

FIG. 6.

FIV Vif fails to bind to Gag in vitro. (A) Autoradiogram of the 35S-labeled in vitro-expressed Vif (lanes 1 to 3) and Gag (lanes 3 to 5) incubated with DMP either alone (lanes 2 and 5) or together (lane 3). (B) As a control, in vitro-expressed FIV Gag polyprotein was digested with FIV protease (PR) (lanes 2 and 4) and then incubated with either the DMP buffer (lane 3) or 1 mM DMP in the same buffer (lane 4). Sizes of markers (M) indicated in kilodaltons. CA, capsid protein; MA, matrix protein.

FIV Vif is equally partitioned between the nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts in FIV-infected cells.

To test our contention that the Vif protein localizes to the nucleus, we made nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts from G355-5 glial cells mock infected or chronically infected with FIV-34TF10 and FIV-PPRchim42 (data not shown). Cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting and incubating the same blot with the anti-Vif MAb followed by anti-p24 MAb after stripping off the first antibody. As shown in Fig. 7A, both the cytoplasmic (lane 2) and nuclear (lane 4) extracts from cells infected with 34TF10 had almost equivalent amounts of Vif. The same blots, on the other hand, showed the presence of both the Gag polyprotein and the 24-kDa capsid protein in the case of the cytoplasmic extract (Fig. 7B, lane 2), whereas the polyprotein was predominant in the nuclear extracts (lane 4).

FIG. 7.

The Vif protein partitions equally between nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts. Equal amounts of protein from cytoplasmic (lanes 1 and 2) and nuclear (lanes 3 and 4) extracts from mock-infected (lanes 1 and 3) or FIV-34TF10-infected cells were resolved by 10 to 20% Tricine SDS-PAGE. The proteins were electroblotted to a nitrocellulose membrane and tested for reactivity to MAb Vif 1-3 (A). The same blot was completely stripped and incubated with the anti-p24 MAb PAK-3-2C1 (B). Positions of markers (M) are indicated in kilodaltons.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have demonstrated that FIV Vif is present in the nucleus of the infected cell. We were able to do this by using a newly generated MAb. Vif1-3, generated against recombinant Vif protein from FIV-34TF10. This MAb is reactive to the Vif from the strain against which it was developed but not to FIV-PPR. The availability of this reagent provided a convenient tool to explore the expression and localization of this protein in cells infected with FIV. Interestingly, the Vif staining excluded the nucleolus, opposite the pattern noted for Rev staining (34). Although binding to the nuclear membrane cannot be excluded, Vif localization was not consistent with exclusive membrane association.

We failed to detect any Vif on either gradient-purified virus or in crude preparations of ultracentrifuged culture supernatants by Western blotting and development using an extremely sensitive enhanced chemiluminescent substrate. There have been a number of studies, almost exclusively in HIV, where Vif has been reported to be present on the virus or to copurify with it (2, 4, 12, 23, 30). The Vif protein has been stated to be present in 60 to 100 copies per virus particle (30), raising the possibility that it may have an important role in the early replication events. A more recent report (6), however, disputes those earlier claims and shows data consistent with the notion that purifying HIV through OptiPrep removes contaminating microvesicles, leading to the detection of <1 Vif molecule per virion. This level of Vif would be within the limits of purification and essentially equal to the contamination expected from cellular proteins (6). Additionally, it has been demonstrated that the packaging of Vif in virions is neither specific nor essential for function and that the level of incorporation depends on cellular expression levels (46). The findings reported here support the conclusions of the latter reports.

MAb Vif1-3 worked well in Western blot analysis, as well as in immunoprecipitations, to detect Vif in glial cells infected with the FIV-34TF10. It could not, however, detect Vif from FIV-PPR, confirming its specificity. Since these isolates have 90% sequence identity, the recognized epitope must lie within the 10% region of variance. Given that the antibody recognized truncated forms of Vif produced in in vitro translation via initiation from methionine residues at positions 24 and 80, the findings indicate that the antibody epitope is C terminal to this region. Experiments are in progress to further map this epitope.

Immunocytochemistry specific to Vif in FIV-infected cells was earlier reported to be cytoplasmic (42). Simon et al. (43), using a rabbit polyclonal antibody, observed a punctate distribution of the protein that included the nucleus, whereas Gag localized exclusively to the cytoplasm. Given the findings of the present study, it is likely that the cytoplasmic localization of Vif is a result of the methanol fixation used in the earlier studies. The use of 2% formaldehyde leads to protein cross-linking with minimal chances for nonspecific leaching of the nuclear proteins. Flow cytometric evaluation of DNA content and nuclear immunofluorescence in mammalian cells using either acetone-methanol, methanol, paraformaldehyde-methanol, or paraformaldehyde followed by Triton X-100 solubilization shows the latter to be optimal for maintaining the molecular architecture of the nucleus (41). These authors postulated that the paraformaldehyde–Triton X-100 combination permeabilizes cells but retains native supramolecular structure, whereas methanol-based fixatives disrupt this structure and randomize the availability of the epitope to the antibody. In addition, permeabilization in 0.2% Triton X-100 should theoretically leave the nuclear membrane intact and help to reveal any specific interactions thereon. It has been demonstrated that the distribution of flavivirus-specific envelope, prM, and NS1 proteins was influenced by whether the cells were fixed with acetone or formaldehyde (53). It has also been determined that the choice of formaldehyde leads to the detection of both cytoplasmic and nuclear human papillomavirus E7 protein in immunofluorescence, whereas acetone-fixed cells show only the cytoplasmic component, using the same panel of MAbs (22). Cytoplasmic localization for HIV-1 Vif has been demonstrated by methanol fixation methods (14, 23, 43). Goncalves et al. (15) used a 4% paraformaldehyde fixation method in their immunocytochemistry studies and found that while HIV-1 Vif was predominantly cytoplasmic, some cells showed light staining of Vif in the nucleus. In light of our finding that FIV Vif is nuclear localized, we predict that HIV Vif follows a similar pattern under identical experimental conditions, although it remains to be shown that FIV Vif and HIV-1 Vif have identical functions. Several attempts were made to perform similar analyses to localize HIV Vif (performed in collaboration with B. Torbett, Scripps Research Institute) as a function of fixation conditions. Unfortunately, the antibodies that we were able to obtain (AIDS Repository catalog no. 2221 [HIV-1HXB2 Vif rabbit antiserum] and 2550 [HIV-1 Vif mouse MAb TG 0001]) all gave high background reactivity with normal cells. Although trends were the same, the results were not suitable for publication. We are currently trying to obtain better antibodies to use for these analyses.

The presence of Vif in the nuclear extract as well as the cytoplasmic extract strengthens our observation that the FIV Vif protein has a primary role in the nucleus of infected cells. Transfection studies using the wild-type HIV-1 expression vector and also the subgenomic vector pgVif showed that Vif was expressed in the nucleus as well as the cytoplasm of HeLa cells at 18 h posttransfection (43). It may be possible that different lentiviruses follow broadly similar mechanisms of cellular interactions and that Vif plays a central role in at least in the context of certain cell types. The role of Vif remains to be elucidated. However, the present findings indicate that the search for a Vif function should concentrate on the nucleus. Continued studies will eventually resolve this issue.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by NIH grants R01 AI25825 and R01 AI40882 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

We thank Danica Lerner, Bruce Torbett, Aymeric de Parseval, and Ying-Chuan Lin for careful reading of the manuscript and for helpful comments. We also thank Ying-Chuan Lin for the gift of FIV protease used in these studies.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. Vol. 2. New York, N.Y: Greene Publishing Associates and John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borman A M, Quillent C, Charneau P, Dauguet C, Clavel F. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vif- mutant particles from restrictive cells: role of Vif in correct particle assembly and infectivity. J Virol. 1995;69:2058–2067. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.4.2058-2067.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bouyac M, Rey F, Nascimbeni M, Courcoul M, Sire J, Blanc D, Clavel F, Vigne R, Spire B. Phenotypically Vif− human immunodeficiency virus type 1 is produced by chronically infected restrictive cells. J Virol. 1997;71:2473–2477. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.2473-2477.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Camaur D, Trono D. Characterization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vif particle incorporation. J Virol. 1996;70:6106–6111. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.9.6106-6111.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Courcoul M, Patience C, Rey F, Blanc D, Harmache A, Sire J, Vigne R, Spire B. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells produce normal amounts of defective Vif− human immunodeficiency virus type 1 particles which are restricted for the preretrotranscription steps. J Virol. 1995;69:2068–2074. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.4.2068-2074.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dettenhofer M, Yu X F. Highly purified human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reveals a virtual absence of Vif in virions. J Virol. 1999;73:1460–1467. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.2.1460-1467.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dignam J D, Lebovitz R M, Roeder R G. Accurate transcription initiation by RNA polymerase II in a soluble extract from isolated mammalian nuclei. Nucleic Acids Res. 1983;11:1475–1489. doi: 10.1093/nar/11.5.1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dignam J D, Martin P L, Shastry B S, Roeder R G. Eukaryotic gene transcription with purified components. Methods Enzymol. 1983;101:582–598. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(83)01039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elder J H, Schnolzer M, Hasselkus-Light C S, Henson M, Lerner D A, Phillips T R, Wagaman P C, Kent S B. Identification of proteolytic processing sites within the Gag and Pol polyproteins of feline immunodeficiency virus. J Virol. 1993;67:1869–1876. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.4.1869-1876.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fan L, Peden K. Cell-free transmission of Vif mutants of HIV-1. Virology. 1992;190:19–29. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)91188-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fisher A G, Ensoli B, Ivanoff L, Chamberlain M, Petteway S, Ratner L, Gallo R C, Wong-Staal F. The sor gene of HIV-1 is required for efficient virus transmission in vitro. Science. 1987;237:888–893. doi: 10.1126/science.3497453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fouchier R A, Simon J H, Jaffe A B, Malim M H. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vif does not influence expression or virion incorporation of gag-, pol-, and env-encoded proteins. J Virol. 1996;70:8263–8269. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.12.8263-8269.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gabuzda D H, Lawrence K, Langhoff E, Terwilliger E, Dorfman T, Haseltine W A, Sodroski J. Role of vif in replication of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in CD4+ T lymphocytes. J Virol. 1992;66:6489–6495. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.11.6489-6495.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goncalves J, Jallepalli P, Gabuzda D H. Subcellular localization of the Vif protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1994;68:704–712. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.2.704-712.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goncalves J, Shi B, Yang X, Gabuzda D. Biological activity of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vif requires membrane targeting by C-terminal basic domains. J Virol. 1995;69:7196–7204. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.11.7196-7204.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grant C K. Purification and characterization of feline IgM and IgA isotypes and three subclasses of IgG. In: Willett B J, Jarrett O, editors. Feline immunology and immunodeficiency. New York, N.Y: Oxford University Press; 1995. pp. 95–107. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hevey M, Donehower L A. Complementation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 vif mutants in some CD4+ T-cell lines. Virus Res. 1994;33:269–280. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(94)90108-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hochuli E, Bannwarth W, Dobeli H, Gentz R, Stuber D. Genetic approach to facilitate purification of recombinant proteins with a novel metal chelate adsorbent. Bio/Technology. 1988;6:1321–1325. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hochuli E, Dobeli H, Schacher A. New metal chelate adsorbent selective for proteins and peptides containing neighbouring histidine residues. J Chromatogr. 1987;411:177–184. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(00)93969-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoglund S, Ohagen A, Lawrence K, Gabuzda D. Role of vif during packing of the core of HIV-1. Virology. 1994;201:349–355. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Janknecht R, de Martynoff G, Lou J, Hipskind R A, Nordheim A, Stunnenberg H G. Rapid and efficient purification of native histidine-tagged protein expressed by recombinant vaccinia virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:8972–8976. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.20.8972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kanda T, Zanma S, Watanabe S, Furuno A, Yoshiike K. Two immunodominant regions of the human papillomavirus type 16 E7 protein are masked in the nuclei of monkey COS-1 cells. Virology. 1991;182:723–731. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90613-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karczewski M K, Strebel K. Cytoskeleton association and virion incorporation of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vif protein. J Virol. 1996;70:494–507. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.1.494-507.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kozak M. Context effects and inefficient initiation at non-AUG codons in eucaryotic cell-free translation systems. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:5073–5080. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.11.5073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kozak M. Regulation of protein synthesis in virus-infected animal cells. Adv Virus Res. 1986;31:229–292. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(08)60265-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laco G S, Fitzgerald M C, Morris G M, Olson A J, Kent S B, Elder J H. Molecular analysis of the feline immunodeficiency virus protease: generation of a novel form of the protease by autoproteolysis and construction of cleavage-resistant proteases. J Virol. 1997;71:5505–5511. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.7.5505-5511.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Le Grice S F, Gruninger-Leitch F. Rapid purification of homodimer and heterodimer HIV-1 reverse transcriptase by metal chelate affinity chromatography. Eur J Biochem. 1990;187:307–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb15306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lerner D L, Elder J H. Expanded host cell tropism and cytopathic properties of feline immunodeficiency virus-PPR subsequent to passage through interleukin-2-independent T cells. J Virol. 2000;74:1854–1863. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.4.1854-1863.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lerner D L, Grant C K, de Parseval A, Elder J H. FIV infection of IL-2-dependent and -independent feline lymphocyte lines: host cells range distinctions and specific cytokine upregulation. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 1998;65:277–297. doi: 10.1016/S0165-2427(98)00162-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu H, Wu X, Newman M, Shaw G M, Hahn B H, Kappes J C. The Vif protein of human and simian immunodeficiency viruses is packaged into virions and associates with viral core structures. J Virol. 1995;69:7630–7638. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.12.7630-7638.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Myers G B, Berzofsky J A, Korber B, Smith R F, Pavlakis G N. Human retroviruses and AIDS 1992: a compilation and analysis of nucleic acid and amino acid sequences. Los Alamos, N.M: Los Alamos National Laboratory; 1992. . ex. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oberste M S, Gonda M A. Conservation of amino-acid sequence motifs in lentivirus Vif proteins. Virus Genes. 1992;6:95–102. doi: 10.1007/BF01703760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pedersen N C, Ho E W, Brown M L, Yamamoto J K. Isolation of a T-lymphotropic virus from domestic cats with an immunodeficiency-like syndrome. Science. 1987;235:790–793. doi: 10.1126/science.3643650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Phillips T R, Lamont C, Konings D A, Shacklett B L, Hamson C A, Luciw P A, Elder J H. Identification of the Rev transactivation and Rev-responsive elements of feline immunodeficiency virus. J Virol. 1992;66:5464–5471. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.9.5464-5471.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Phillips T R, Talbott R L, Lamont C, Muir S, Lovelace K, Elder J H. Comparison of two host cell range variants of feline immunodeficiency virus. J Virol. 1990;64:4605–4613. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.10.4605-4613.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Porath J, Carlsson J, Olsson I, Belfrage G. Metal chelate affinity chromatography, a new approach to protein fractionation. Nature. 1975;258:598–599. doi: 10.1038/258598a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reddy T R, Kraus G, Yamada O, Looney D J, Suhasini M, Wong-Staal F. Comparative analyses of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) and HIV-2 Vif mutants. J Virol. 1995;69:3549–3553. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.6.3549-3553.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sakai H, Shibata R, Sakuragi J, Sakuragi S, Kawamura M, Adachi A. Cell-dependent requirement of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vif protein for maturation of virus particles. J Virol. 1993;67:1663–1666. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.3.1663-1666.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schimenti K J, Jacobberger J W. Fixation of mammalian cells for flow cytometric evaluation of DNA content and nuclear immunofluorescence. Cytometry. 1992;13:48–59. doi: 10.1002/cyto.990130109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shacklett B L, Luciw P A. Analysis of the vif gene of feline immunodeficiency virus. Virology. 1994;204:860–867. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Simon J H, Fouchier R A, Southerling T E, Guerra C B, Grant C K, Malim M H. The Vif and Gag proteins of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 colocalize in infected human T cells. J Virol. 1997;71:5259–5267. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.7.5259-5267.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Simon J H, Gaddis N C, Fouchier R A, Malim M H. Evidence for a newly discovered cellular anti-HIV-1 phenotype. Nat Med. 1998;4:1397–1400. doi: 10.1038/3987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Simon J H, Malim M H. The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vif protein modulates the postpenetration stability of viral nucleoprotein complexes. J Virol. 1996;70:5297–5305. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.8.5297-5305.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Simon J H, Miller D L, Fouchier R A, Malim M H. Virion incorporation of human immunodeficiency virus type-1 Vif is determined by intracellular expression level and may not be necessary for function. Virology. 1998;248:182–187. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Simon J H, Miller D L, Fouchier R A, Soares M A, Peden K W, Malim M H. The regulation of primate immunodeficiency virus infectivity by Vif is cell species restricted: a role for Vif in determining virus host range and cross-species transmission. EMBO J. 1998;17:1259–1267. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.5.1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sova P, Volsky D J. Efficiency of viral DNA synthesis during infection of permissive and nonpermissive cells with vif-negative human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1993;67:6322–6326. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.10.6322-6326.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Talbott R L, Sparger E E, Lovelace K M, Fitch W M, Pedersen N C, Luciw P A, Elder J H. Nucleotide sequence and genomic organization of feline immunodeficiency virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:5743–5747. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.15.5743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tomonaga K, Norimine J, Shin Y S, Fukasawa M, Miyazawa T, Adachi A, Toyosaki T, Kawaguchi Y, Kai C, Mikami T. Identification of a feline immunodeficiency virus gene which is essential for cell-free virus infectivity. J Virol. 1992;66:6181–6185. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.10.6181-6185.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Trono D. HIV accessory proteins: leading roles for the supporting cast. Cell. 1995;82:189–192. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90306-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.von Schwedler U, Song J, Aiken C, Trono D. Vif is crucial for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 proviral DNA synthesis in infected cells. J Virol. 1993;67:4945–4955. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.8.4945-4955.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Westaway E G, Goodman M R. Variation in distribution of the three flavivirus-specified glycoproteins detected by immunofluorescence in infected Vero cells. Arch Virol. 1987;94:215–228. doi: 10.1007/BF01310715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yang X, Goncalves J, Gabuzda D. Phosphorylation of Vif and its role in HIV-1 replication. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:10121–10129. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.17.10121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]