Abstract

Virion infectivity factor (Vif) is a protein encoded by human immunodeficiency virus type I (HIV-1) and is essential for viral replication. It appears that Vif functions in the virus-producing cells and affects viral assembly. Viruses with defects in the vif gene (vif−) generated from the “nonpermissive cells” are not able to complete reverse transcription. In previous studies, it was demonstrated that defects in the vif gene also affect endogenous reverse transcription (ERT) when mild detergents were utilized to permeabilize the viral envelope. In this report, we demonstrate that defects in the vif gene have much less of an effect on ERT if detergent is not used. When ERT was driven by addition of deoxyribonucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs) at high concentrations, certain levels of plus-strand viral DNA could also be achieved. Interestingly, if vif− viruses, generated from nonpermissive cells and harboring large quantities of viral DNA generated by ERT, were allowed to infect permissive cells, they could partially bypass the block at intracellular reverse transcription, through which vif− viruses without dNTP treatment could not pass. Consequently, viral infectivity can be partially rescued from the vif− phenotype. Based on our observations, we suggest that vif defects may cause the reverse transcription complex (RT complex) to become sensitive to mild detergent treatments within HIV-1 virions and become unstable in the target cells, such that the process of reverse transcription cannot be efficiently supported. Further dissection of RT complexes of vif− viruses may be key to uncovering the molecular mechanism(s) of Vif in HIV-1 pathogenesis.

Human and simian immunodeficiency viruses are complex retroviruses. Their genomes contain not only gag, pol, and env genes but also several regulatory and accessory genes such as tat, rev, vif, nef, vpr, and vpu. The vif (virion infectivity factor) gene is required for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) replication in vivo and in vitro for certain cell types (so-called “nonpermissive cells”), such as peripheral blood lymphocytes, macrophages, and H9 T cells (15, 17, 18, 44, 47). It appears that Vif functions in the virus-producing cells and affects viral assembly (2, 17, 47). It has been shown that the Vif protein is not specifically incorporated into virions (9, 13, 42). The infectivity of vif− virions generated from nonpermissive cells is dramatically decreased compared to that of the wild type (15, 17, 18, 44, 47). Vif-defective HIV-1 virions have an altered morphology and cannot perform intracellular reverse transcription and endogenous reverse transcription (ERT) when detergent is utilized to permeabilize the viral envelope (5, 6, 11, 23, 24, 43, 47). For ERT, it has been shown that the impairment of reverse transcription is global (23). Compared to that in wild-type viruses, the level of reverse transcription achieved in Vif-defective virus was significantly decreased. It has been reported that there are two types of defects in the processing of intracellular reverse transcription. The first one occurs during negative-strand viral DNA synthesis in certain cells, such as H9 and MT4 T cells (43, 47). This is a global defect during reverse transcription. Another problem is the impairment of the accumulation of viral DNA in some target cells such as C8166, possibly because of instability of the viral nucleoprotein complex (41).

Our previous studies have demonstrated that, without detergent, ERT can be processed only in the presence of deoxyribonucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs) and polyamines and participates in the viral life cycle. As such, we have termed this stage the in viral life cycle natural ERT (NERT) (51). We have also shown that the C terminus of gp41 can penetrate the viral envelope and allows the dNTPs to pass through the envelope (49). The virus infectivity for quiescent or initially quiescent cells can be enhanced by intravirion reverse transcription driven by low concentrations (e.g., 50 nM) of dNTPs and by some physical microenvironments, such as seminal fluids (51). To increase viral infectivity for replicating cells, however, dNTPs at high concentrations (e.g., 5 mM) is required to synthesize increased intravirion DNA (53). This may be due to virions harboring large quantities of viral DNA, which can bypass certain negative factors which inhibit the efficiency of intracellular reverse transcription. As intravirion reverse transcription can enhance viral infectivity, several groups have adopted this strategy for treating HIV-1-derived vectors and thus enhancing the transduction efficiency (3, 22, 26, 35).

As defects in the vif gene impair intracellular reverse transcription and ERT with detergent, we asked whether NERT might also be affected and, further, whether the function of Vif can be complemented by driving intravirion reverse transcription with dNTPs at high concentrations. Our studies demonstrated that instability of the reverse transcription complex (RT complex) in the target cells can be partially bypassed by driving intravirion reverse transcription with dNTPs at high concentrations. These data support the hypothesis that the instability of RT complexes in target cells is mainly responsible for the phenotype of a defective vif gene.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid constructions.

An infectious HIV-1 clone with a deletion in the vif region (234-bp deletion), pNL4-3Δvif, was constructed by replacing the AgeI-EcoRI fragment of pNL4-3 with that of p197-1 (5′ half mutant of pNL4-3 with vif deletion) (21). To construct an infectious HIV-1 clone with deletions in both the vif and env regions, pNL4-3ΔvifΔenv, and an infectious HIV-1 clone with a deletion only in the env region, pNL4-3Δenv, the BglII-BglII fragment (nucleotides 7031 to 7611) was deleted from pNL4-3Δvif and pNL4-3, respectively. The pMD.G construct (expressing vesicular stomatitis virus [VSV] env) was obtained from D. Trono (35).

Generation of an H9 cell line which consistently produces vif− viruses.

pNL4-3Δvif (10 μg) was transfected into human rhabdomyosarcoma (RD) cells by the calcium phosphate coprecipitation method (49). After 72 h, H9 cells were added, and the coculture was allowed to progress for 48 h. H9 cells were then harvested. By limiting-dilution analyses, single H9 cells were isolated and allowed to proliferate (46). After approximately 104 H9 cells were grown from a single cell, HIV-1NL4-3Δvif-producing H9 cell clones were screened to detect HIV-1 p24 antigen in the supernatant, via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA). H9 cell clones which were HIV-1 p24 antigen positive in the supernatant were then selected, further propagated, and frozen at −140°C. Additionally, pNL4-3 was transfected into RD cells to generate wild-type HIV-1 viruses. The wild-type viruses were then allowed to infect H9 cells. The infected H9 cells were maintained in the culture for several months. These chronically infected H9/HIV-1NL4-3 cells were than utilized as the controls for the following experiments.

ERT.

After growth in fresh, conditioned medium for 2 days, the chronically infected H9/HIV-1NL4-3 cells and H9/HIV-1NL4-3Δvif cell clones, which consistently produced vif− viruses, were pelleted at 300 g for 10 min. The HIV-1 wild-type and vif− virion-containing supernatants were then aliquoted and mixed with a NERT-stimulating cocktail (1 mM dNTPs [Sigma], 30 μM spermidine [pH 7.2; Sigma], 2.5 mM MgCl2). The ERT reaction was then allowed to progress at 37°C for 4 h. For nascent viral DNA detection, the virions were then treated with DNase at 37°C for 15 min. DNase was heat inactivated, and viral DNA was extracted and amplified by PCR with various primer pairs. As described in previous studies (48, 50–53), the RU5 region (negative-strand “strong-stop” DNA) was detected using the primer/probe set M667-AA55/SK31, the U3 region was detected by the primer/probe set U31-U32/U33, the gag region was detected by the primer/probe set SK38-SK39/SK19, and the region in the RU5 primer binding site (PBS) 5′ noncoding region (5NC), which amplified reverse transcripts consisting of moieties containing positive-strand DNA after the second template switch and past the PBS, were detected by the primer/probe set M667-M661/SK31. Analysis by Southern blotting was performed as described previously (48, 50–53).

Quantitative PCR analysis of intracellular HIV-1 reverse transcription.

HIV-1NL4-3 and HIV-1NL4-3Δvif virions produced from H9 cells were mixed with a NERT-stimulating cocktail, as described above, or left without treatment. After incubation at 37°C for 4 h, the mixtures were placed onto a 20% sucrose-TN solution (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 100 mM NaCl) and virions were pelleted in an A481 rotor (Sorvall) at 90,000 × g for 1 h. The virions (60 ng of HIV-1 p24 antigen equivalents) were resuspended in RPMI 1640 media and allowed to incubate with 3 × 106 Jurkat or C8166 T-cell lines at 4°C for 10 min and then at 37°C for 6 h. As a control, heat-inactivated HIV-1 virions (56°C for 1 h) were also used to infect these target cells. The unbound viruses were washed off with phosphate-buffered saline, and soluble DNA was eliminated by DNase treatment at 37°C for 30 min. The infected cells were then aliquoted into three portions. One portion was immediately added to lysing buffer and frozen, while the two other cell aliquots were cultured at 37°C. At 24 and 48 h postinfection, the cells were harvested. Viral DNA was extracted from the infected cells via a “quick-lysis” methodology and amplified by PCR with various primer pairs. Analysis by Southern blotting was then performed as described previously (48, 50–53). Further, two-long terminal repeat (2-LTR) circular DNA was detected by a “nested” PCR with outer primer set M667-U32, followed by inner primer set 2LTR-U5/2LTR-U5. Analysis by Southern blotting was then performed as described previously (31). The positive control for the 2-LTR circular DNA was from the PCR product of extrachromosomal DNA, which was extracted from a coculture of H9/HIV-1NL4-3 and H9 cells, amplified with primer set M667-U32, and then diluted.

Viral infectivity assays.

HIV-1NL4-3 and HIV-1NL4-3Δvif virions (1 ng of HIV-1 p24 antigen equivalents) produced from H9 cells were mixed with the NERT cocktail, various reagents, or left untreated. After incubation at 37°C for 4 h, the virions were then allowed to infect 2 × 106 Jurkat or C8166 cells at 37°C for 4 h. The unbound viruses were washed off via three vigorous washes with phosphate-buffered saline. The infected cells (2 × 106) were then cultured, in duplicate, in 2 ml of RPMI 1640 medium plus 10% fetal calf serum. After overnight incubation, the supernatants (0.5 ml) were collected for HIV-1 p24 antigen detection on day 0. The cells were then cultured in 2 ml of RPMI 1640 medium plus 10% fetal bovine serum. Portions of the supernatants (0.5 ml) were collected at various time points. The HIV-1 p24 antigen levels were quantitated by ELISA.

Single-round infection assays (multinuclear activation of a galactosidase indicator [MAGI] assay).

pNL4-3ΔvifΔenv and pNL4-3Δenv constructs were cotransfected with the pMD.G construct into H9 cells using the SuperFect system (Qiagen, Valencia, Calif.). The manufacturer's protocol was followed. Seventy-two hours after transfection, the supernatants were collected and the pseudotyped viral particles were pelleted by ultracentrifugation at 90,000 × g for 2 h. The resuspended viral particles were normalized using p24 antigen detected by ELISA (DuPont) and treated with the NERT cocktail for 4 h at 37°C. The viruses (4.0 ng of p24 equivalents) were then allowed to infect HeLaCD4-LTR/β-gal cells (27). At 72 h postinfection, the infected cells were fixed and stained for the detection of β-galactosidase activity, as described previously (28). Briefly, HeLaCD4-LTR/β-gal cells were fixed with 0.2% glutaraldehyde and 2% formaldehyde for 5 min at room temperature. The cells were then washed with phosphate-buffered saline three times, and X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside) solution (X-Gal [1 mg/ml] predissolved in dimethylformamide, 4 mM potassium ferricyanide, 4 mM potassium ferrocyanide, 2 mM MgCl2 in phosphate-buffered saline) was added. The staining was allowed to develop at 37°C for 4 h. The cells which turned dark blue under visible light were counted as positive.

RESULTS

Generation of H9 cell clones which consistently produce vif− viruses.

To produce vif− virus from nonpermissive cells such as peripheral blood lymphocytes, macrophages, and H9 T cells, transfection of an infectious HIV-1 clone with a deletion in the vif region into these cells could be utilized. However, this assay is neither convenient nor able to generate large quantities of vif− viruses, because of low efficiency of transfection into these nonpermissive cells. Further, it is difficult to eliminate the remaining plasmid in the supernatant, which could be indistinguishable from newly synthesized viral DNA by intravirion or intracellular reverse transcription. To generate large quantities of vif− viruses from nonpermissive cells, we followed a strategy used to select single HIV-1NL4-3Δvif-infected H9 cells, which are able to generate vif− viruses consistently, via a limiting dilution assay (6). To this end, human RD cells were transfected with pNL4-3Δvif (49). After 4 days, H9 cells were mixed with the RD cells. This coculture procedure assured that some of the H9 cells would be infected and produce vif− viruses. As H9 cells are nonpermissive, the viruses generated from an H9 cell are unable to infect other H9 cells. By limiting-dilution assays, single H9 cells were isolated and allowed to proliferate. HIV-1NL4-3Δvif-producing H9 cell clones were screened by the detection of HIV-1 p24 antigen in the supernatant.

Ten H9 cell clones generating vif− viruses, from a total of approximately 300 clones, were selected by this method. The amount of viral particles detected by HIV-1 p24 antigen was approximately 0.1 to 2 ng of p24 antigen equivalents/ml. Interestingly, if the cultures were maintained for a longer time, up to 1 month, most of these positive clones (8 of 10) gradually stopped generating viral particles. Only two clones (clones 54 and 175) could consistently generate virus particles for up to 1 year. The p24 antigen level generated by clone 175 was approximately 0.1 to 0.5 ng/ml, while that generated by clone 54 was approximately 0.8 to 3.6 ng/ml. As such, we utilized clone 54 for all the following studies. Reverse transcription-PCR was performed to detect the vif regions of virion-associated RNA of vif− viruses generated by clone 54. Deletion in the vif gene was confirmed, as the PCR product for the vif region generated from clone 54 was 234 bp shorter than that generated from the wild type (data not shown).

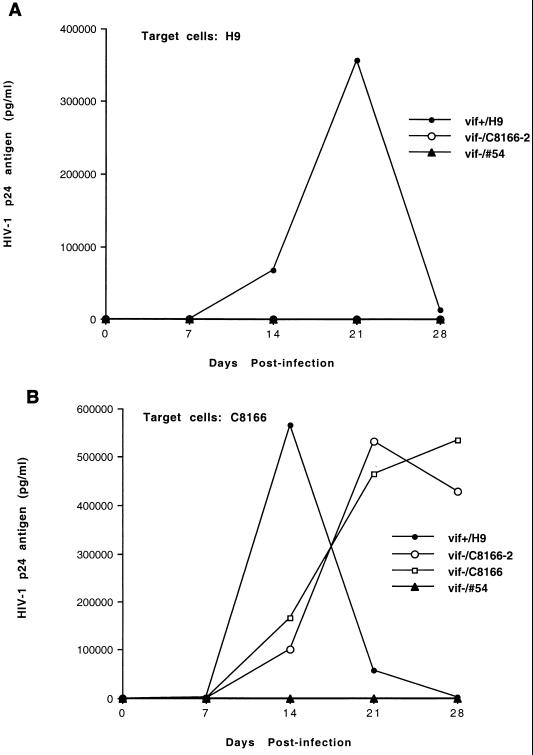

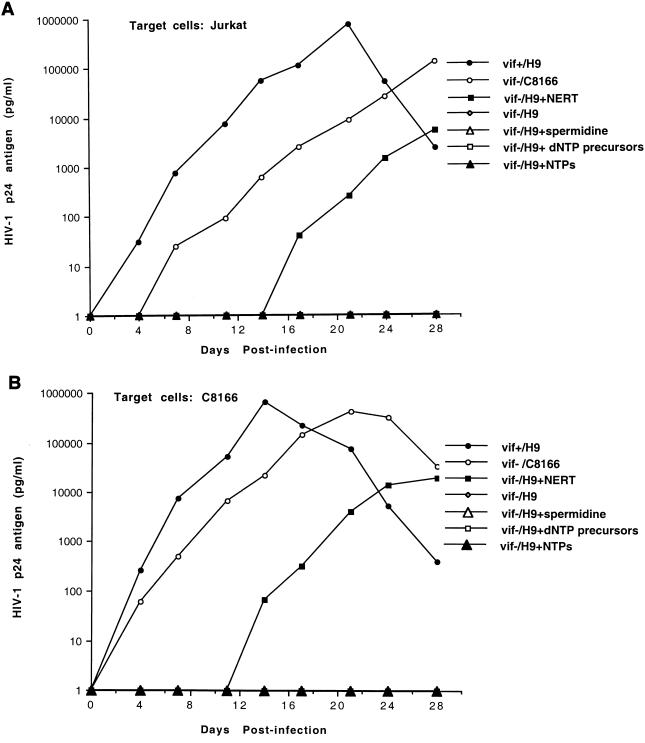

To test the infectivities of vif− viruses generated from cell clone 54, various human T-cell lines, such as H9 and C8166, were infected by cell-free viruses. Figure 1 indicates that vif− viruses generated from cell clone 54 did not infect H9 or C8166 cells. As controls, viruses from HIV-1NL4-3-infected H9 cells or from HIV-1NL4-3Δvif-infected C8166 cells were also allowed to infect these cells. vif− viruses generated from C8166 were able to replicate in target C8166 cells (Fig. 1). As such, our data support the hypothesis that a defect of the vif gene affects the viral life cycle in the virus-producing cells (2, 17, 47). Previous studies indicated that the replication kinetics of vif− viruses generated from C8166 in the target C8166 cells was almost the same as that of wild-type HIV-1 viruses (39, 40a). However, our data (Fig. 1b) indicated that the replication kinetics of vif− viruses generated from C8166 cells in the target C8166 cells was slightly slower than that of wild-type HIV-1 viruses. This minor difference may be due to the variations in the different experiments. When vif− viruses generated from the cell clone 54 were treated with a NERT cocktail and allowed to establish infection in C8166 cells (see below), vif− viruses generated from these C8166 cells again had infectivities for fresh target C8166 cells similar to those of the wild-type HIV-1 viruses, further supporting this conclusion (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Infectivities of HIV-1 viruses generated from various T-cell lines. The vif− viruses (1 ng of HIV-1 p24 antigen equivalents), generated from H9 cells (clone 54 cells) or from C8166 cells, were allowed to infect 2 × 106 H9 (A) or C8166 (B) cells at 37°C for 4 h. As a control, wild-type HIV-1 viruses were also allowed to infect these cells. After the unbound viruses were washed off, the cells were cultured and portions of the supernatants were collected at the specified time points for detection of HIV-1 p24 antigen. C8166-2, C8166 cells which were infected by vif− viruses generated from clone 54 cells after the vif− viruses were treated with a NERT cocktail (see Fig. 4B).

Impact of a Vif defect on intravirion reverse transcription.

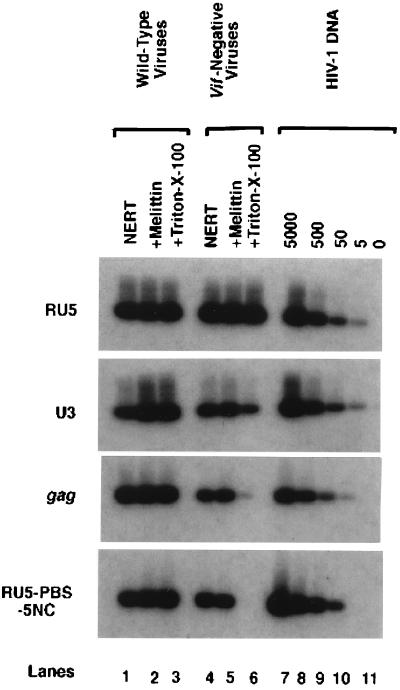

To investigate the effect of a vif− gene on intravirion reverse transcription, viruses generated from clone 54 were treated with dNTPs and spermidine, with or without mild detergent or amphipathic peptide (melittin) (51). As a control, wild-type HIV-1 virions generated from chronically infected H9 cells were also treated by the same procedure. To monitor the viral DNA synthesis at various regions, primer pairs at RU5, U3, gag, and RU5-PBS-5NC were utilized in quantitative PCR analyses (48). Figure 2 indicates that negative-strand strong-stop DNA (RU5 region) can be synthesized normally in vif− viruses. However, compared with ERT in wild-type HIV-1 virions, a global decrease of ERT in vif− viruses was demonstrated. Interestingly, the defect of ERT of vif− virions was significantly altered when different agents were utilized to permeabilize the viral envelope. When melittin, an amphipathic peptide, was utilized to permeabilize the viral envelope, the defect of ERT was slight (lane 5) (49). Without detergent or amphipathic peptide, NERT of vif− virus was decreased (lane 4) compared to that of wild-type virus without detergent or amphipathic peptide treatments (lane 1). However, compared to NERT of vif− viruses treated with melittin (lane 5), it was only slightly decreased (lane 4). It is notable that NERT of vif− viruses can still lead to some plus-strand DNA synthesis (lane 4). Strikingly, when mild detergent (0.01% Triton X-100) was utilized, the defect of ERT was more severe (Fig. 2, lane 6) in vif− viruses. Few reverse transcripts could reach the region of gag DNA and plus-strand DNA. As the synthesis of negative-strand strong-stop DNA (RU5 region) is almost the same as that of the wild type, while that of U3 DNA is significantly decreased, Triton X-100 may severely impair the first template transfer during reverse transcription.

FIG. 2.

Effect of a vif defect on intravirion reverse transcription. The HIV-1 wild-type and vif− virions generated from H9 cells were mixed with a NERT cocktail. In addition, melittin (15 μg/ml) or Triton X-100 (0.01%) was added to the reaction system. The ERT reaction was then allowed to progress at 37°C for 6 h. The DNase-resistant intravirion DNA was extracted and amplified by PCR with various primer pairs. As described in previous studies, the RU5 region (negative-strand strong-stop DNA) was detected using the primer/probe set M667-AA55/SK31, the U3 region was detected by the primer/probe set U31-U32/U33, the gag region was detected by the primer/probe set SK38-SK39/SK19, and the RU5-PBS-5NC region, which amplified reverse transcripts consisting of moieties containing plus-strand DNA after the second template switch and past the PBS, was detected by the primer/probe set M667-M661/SK31 (48, 50–53).

Impact of a Vif defect on intracellular reverse transcription.

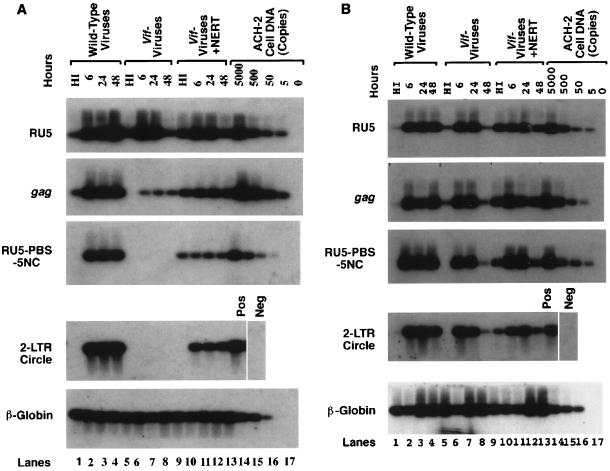

It has been reported that a defect in the vif gene may affect negative-strand DNA synthesis when some cells, such as H9 or MT4, are chosen as the targets (43, 47). Conversely, when other cells such as C8166 were chosen as the targets, both negative-strand DNA and plus-strand DNA (at least the RU5-PBS-5NC region) could be synthesized, while viral DNA could not be accumulated, possibly because of the instability of the nucleocapsid complex. To confirm this phenomenon, C8166 and Jurkat cells were infected with vif− viruses at the same time. The vif− viruses that were treated with a NERT cocktail to initiate intravirion reverse transcription were also allowed to infect these cells at the same time point. Figure 3A indicates that in the Jurkat cells, as in other target cells, the negative-strand DNA synthesis of vif− viruses is severely impaired at several time points, except for the synthesis of negative-strand strong-stop DNA (lanes 4 to 8) (43, 47). Conversely, in C8166 cells, negative-strand DNA and RU5-PBS-5NC plus-strand DNA can be synthesized by the vif− viruses at 24 h postinfection (Fig. 3B). Interestingly, synthesis of 2-LTR circular DNA can also be completed at 24 h postinfection (31). At 48 h postinfection, however, all viral DNAs, including 2-LTR circular DNA, were significantly decreased. This result is consistent with the observations by others (41). Of note, it has been demonstrated that the formation of 2-LTR DNA results from the ligation of the 5′ and 3′ blunt ends of double-strand viral DNA and occurs only after the synthesized viral DNA has entered the nucleus (38). As such, the degradation of viral DNA of vif− viruses in C8166 cells could also have occurred in the nucleus. To exclude the possibility that the decrease of viral DNA of vif− viruses at 48 h is due to lack of reinfection, 3′-azido-3′-deoxythymidine (AZT) was utilized at 24 h postinfection to stop the newly synthesized DNA of wild-type viruses. Viral DNA of wild-type viruses at 48 h postinfection was not significantly altered even after AZT treatment, suggesting that the accumulation of viral DNA from the first round of infection could extend up to 48 h postinfection.

FIG. 3.

Effect of a vif defect and NERT on intracellular reverse transcription. HIV-1NL4-3 and HIV-1NL4-3Δvif virions produced from H9 cells were mixed with a NERT cocktail or left untreated. After incubation at 37°C for 4 h, the virions were concentrated via ultracentrifugation. The virions (60 ng of HIV-1 p24 antigen equivalents) were incubated with Jurkat (A) or C8166 (B) T-cell lines at 4°C for 10 min and then at 37°C. As a control, heat-inactivated (HI) HIV-1 virions (56°C for 1 h), inactivated after stimulation by NERT in the relevant infections, were also used to infect these target cells. At 6, 24, and 48 h postinfection, the cells were harvested. Viral DNA was extracted from the infected cells via a quick-lysis methodology and amplified by PCR with various primer pairs for different regions of viral DNA. (C) At 24 h postinfection, AZT (10 μM) was added to C8166 cells, which were infected by the indicated viruses. The cells were then harvested at 48 h postinfection, and viral DNA was extracted from the infected cells via a quick-lysis methodology and amplified by PCR.

Stimulation of NERT can partially overcome the blockage in early events of the viral life cycle for vif− viruses.

In both Jurkat and C8166 cell lines, we investigated the impact of NERT on the intracellular reverse transcription of vif− viruses. Figure 3A shows that, in Jurkat cells, viral DNA synthesized in the virions can be carried into the cells and that some moieties can complete RU5-PBS-5NC plus-strand DNA synthesis, form 2-LTR circular DNA, and maintain the newly synthesized DNA in the cells up to 48 h (lanes 9 to 12). This result indicated that the reverse transcription machinery within vif− virions is less affected by a vif defect than that within newly infected Jurkat cells. Conversely, at 48 h postinfection, the amount of vif− viral DNA in C8166 cells which were infected by NERT-initiated virions was higher than that in cells infected by untreated vif− virions, indicating that the stability of viral DNA of vif− viruses in C8166 cells could be enhanced by the process of reverse transcription within cell-free virions (Fig. 3B, lane 12). Alternatively, this result may suggest that the instability of newly synthesized viral DNA of vif− viruses in C8166 cells could be due to defects during reverse transcription. As with full-length negative-strand DNA, some plus-strand DNA (RU5-PBS-5NC region) and both negative- and plus-strand (at the 5′ and 3′ ends) viral DNA (2-LTR circular DNA) were synthesized properly in C8166 cells. Thus, this defect of viral DNA synthesis is likely to be in the process of plus-strand DNA synthesis in the center of the viral genome.

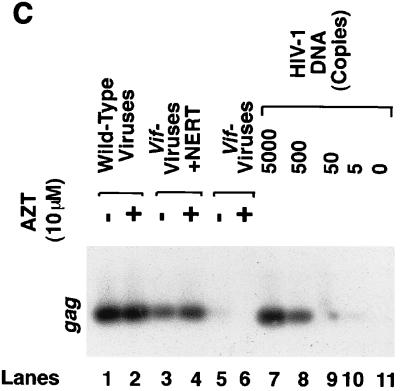

Based on the above observations, we hypothesize that the viral infectivity of vif− viruses from nonpermissive cells could be rescued by driving intravirion reverse transcription prior to infection of target cells. vif− viruses generated from clone 54 cells were treated with the NERT cocktail to initiate NERT and were then allowed to infect Jurkat or C8166 cells. As controls, vif− viruses generated from clone 54 cells without treatment by the NERT cocktail and wild-type HIV-1 viruses generated from chronically infected H9 cells were also allowed to infect Jurkat or C8166 cells. Figure 4 illustrates that vif− viruses generated from clone 54 cells without treatment with dNTPs and spermidine did not yield any infection of the target cells in up to 28 days, while vif− viruses generated from the clone 54 cell line by treatment with dNTPs and spermidine could establish viral infection in either Jurkat or C8166 cells. As controls, spermidine (30 μM) alone, ribonucleoside triphosphates (1 mM), or deoxyribonucleosides (precursors of dNTPs) (1 mM) were utilized to treat vif− viruses generated from cell clone 54. vif− viruses treated by these reagents were allowed to infect C8166 or Jurkat cells, and no viral infection was observed in these treatments. These controls support the hypothesis that NERT is important in rescuing the viral infectivity of vif− viruses generated from nonpermissive cells.

FIG. 4.

Viral infectivity after vif− virions were treated with a NERT cocktail. vif− virions (1 ng of HIV-1 p24 antigen equivalents) generated from H9 cells (clone 54 cells) were treated with a NERT cocktail, other reagents, or left untreated at 37°C for 4 h. The viruses were then allowed to infect Jurkat (A) or C8166 (B) cells. As controls, vif− virions generated from C8166 cells or wild-type viruses from H9 cells were also used to infect these cells. The infection was allowed to progress at 37°C for 4 h. The unbound viruses were washed off, and the infected cells were then cultured. Portions of the supernatants were collected at the specified time points. The HIV-1 p24 antigen levels were quantitated by ELISA.

To further confirm this phenomenon, a single-round infection was tested. pNL4-3ΔvifΔenv and pNL4-3Δenv were cotransfected, along with the pMD.G construct containing the VSV env gene, into H9 cells. Seventy-two hours after transfection, the supernatants were collected and the pseudotyped viral particles were pelleted by ultracentrifugation. The resuspended viral particles were normalized for p24 antigen and treated with the NERT cocktail. The viruses were then allowed to infect HeLaCD4-LTR/β-gal cells (MAGI assay) (27). As no envelope gene is associated with the genomic RNA, only a single round of infection could take place. Figure 5 demonstrates that the viral infectivity of vif− virions generated from H9 cells could be directly enhanced by the initiation of intravirion reverse transcription.

FIG. 5.

Impact of NERT upon vif− viruses in a single-round viral infection assay (MAGI assay). pNL4-3ΔvifΔenv (ΔEΔvif) or pNL4-3Δenv (ΔE) plasmids were cotransfected with pMD.G (containing VSV env) into H9 cells to generate pseudotyped viral particles. After concentration via ultracentrifugation, the viral particles were normalized by p24 antigen levels and treated with the NERT cocktail for 4 h at 37°C. The viruses were then allowed to infect HeLaCD4-LTR/β-gal cells (27). After 72 h, the cells were fixed and stained for the detection of β-galactosidase activity. The cells that turned dark blue were considered to have been infected. This figure is representative of three independent experiments. Values are means ± standard deviation.

DISCUSSION

In this report, we have demonstrated that vif− viruses generated from nonpermissive cells may have a dysfunctional RT complex, such that reverse transcription cannot be properly processed. Unfortunately, our knowledge regarding the RT complexes of wild-type HIV-1 viruses is relatively limited and data accumulated to date are from somewhat indirect evidence. In addition to the reverse transcription and integration enzymes, viral genomic RNA, and tRNAlys, Ncp7 should be part of the RT complex, as Ncp7 is tightly associated with genomic RNA and plays an important role in the initiation, processivity, and strand transferal of reverse transcription (12, 29, 30, 36). It has been demonstrated that some mutations in the Ncp7 region have a limited effect on RNA encapsidation and viral protein maturation but were associated with a strong reduction of viral DNA synthesis and instability in the target cells (45). However, it remains controversial whether p24, the major capsid protein which is the shell of the viral core in the cell-free virions, is in the RT complex. As the major capsid protein (p30) of murine leukemia virus (MLV) was found to be in the preintegration complex, it was hypothesized that p30 should be part of the RT complex and that reverse transcription occurs within the viral core or viral core-derived particle (within the major capsid protein) (7). Further, the murine Fv1 gene, which is believed to be from endogenous gag sequences, can block viral DNA synthesis (1). Some mutations in p30 capsid protein can relieve this block (4, 37). This phenomenon further indicates that the capsid protein of MLV is involved in reverse transcription. For HIV-1, however, p24 is not copurified with the reverse transcription machinery and/or preintegration complex in newly infected cells (8, 14, 19, 20, 33). Furthermore, we recently demonstrated that the morphology of the viral core of wild-type HIV-1 dramatically changed during intravirion reverse transcription, suggesting that HIV-1 reverse transcription may not take place within a fully intact viral core (H. Zhang, G. Dornadula, J. Orenstein, and R. J. Pomerantz, submitted for publication). Nevertheless, p24 may still supply a three-dimensional structure for efficient reverse transcription, especially during template switching.

Recently, we have demonstrated that Vif is an RNA binding protein and an integral component of the mRNP complex of viral RNA (Zhang et al., submitted). Vif proteins in mRNP complexes of viral RNA could initially bind to NcP7 domains of the Gag precursor to mediate the engagement of HIV-1 genomic RNA to Gag precursors. If Vif is not expressed in nonpermissive cells, the genomic viral RNA may be damaged by the hostile environment of the cytoplasm, i.e., by endogenous inhibitors described by others (40), or the interaction between genomic RNA and the NcP7 domain of Gag precursor may be improperly processed (32, 40; Zhang et al., submitted). As a result, the folding and condensation of genomic RNA would occur in a dysfunctional manner and a virion generated from such a producing cell would have morphological alterations. The electron density substance (the RNA-Ncp7 complex is most likely part of this substance) may be partially within the viral core but at the lateral body (24). As the normal structure of the nucleocapsid complex has been altered, reverse transcription could not be accomplished properly.

In this report, we have demonstrated that vif− viruses have much less of an effect upon ERT if detergent is not utilized (Fig. 2, lane 4). When NERT was driven by the addition of dNTPs at high concentrations, certain quantities of plus-strand viral DNA could also be synthesized. vif− viruses harboring more viral DNA, generated by NERT, can bypass the block at intracellular reverse transcription through which vif− viruses without dNTP treatment cannot pass. The reverse transcription process of vif− viruses within virions may have some advantages over that in the target cells. (i) RT complexes of vif− viruses may be relatively stable within virions. Some essential components for RT complexes of vif− viruses may be obligatorily maintained by the viral envelope. (ii) Improperly folded genomic RNA of vif− viruses may be exposed to an RNase-like substance(s) in the target cells and thus would not serve as an intact template for the reverse transcription process. Intravirion reverse transcription may avoid this possible mechanism of damage. Compared to those of wild-type HIV-1 viruses, however, the infectivities of vif− viruses generated from nonpermissive cells with initiated NERT were still low. This partial recovery of viral infectivity could be due to several causes. (i) Intravirion reverse transcripts, even driven with dNTPs at high concentrations and optimized with mild detergent or amphipathic peptide, are still of heterogeneous lengths, as the limited space within virions could not allow the completion of reverse transcription (51). (ii) Natural pores generated by amphipathic domains at the C terminus of gp41 may not be numerous enough or of sufficient size to allow maximal quantities of dNTPs into virions to fuel intravirion reverse transcription (49, 51). (iii) Other impairments caused by the vif defect, besides that in reverse transcription, may also exist, such that intravirion reverse transcription could not completely rescue viral infectivity (5).

We have also demonstrated that in some target cells, such as Jurkat, a defect of the vif gene causes a global dysfunction during the process of intracellular reverse transcription. In these circumstances, intracellular reverse transcription cannot even process the negative-strand viral DNA. However, it has also been reported that the accumulation of vif− viral DNA is affected in some target cells (i.e., C8166) (41). Our data support this observation. As the synthesis of negative-strand DNA, RU5-PBS-5NC plus-strand DNA, and the plus strands at the 5′ and 3′ ends of viral DNA (2-LTR circular DNA) is not affected and as NERT can increase the stability of viral DNA and also partially rescue viral infectivity, we hypothesized that defects of plus-strand DNA synthesis in the center of the HIV-1 genome could be responsible for the instability of vif− viral DNA in C8166 cells. It is well known that plus-strand DNA synthesis of lentiviruses is a discontinuous process (10, 25). There is a central polypurine tract, which functions as a second initiation site for viral plus-strand DNA synthesis (10, 16). Moreover, viral DNA containing discontinuous plus strands is competent for integration (34). Based on our data, we propose that the completion of the central part of plus-strand viral DNA could be important for the stability of vif− viral DNA in the target cells. How a defect in the vif gene impairs this process merits further evaluation. Conversely, it will be interesting to further investigate why the defect in the reverse transcription of vif− viruses occurs during negative-strand viral DNA synthesis in some cells (e.g., Jurkat and H9), while occurring during plus-strand viral DNA synthesis in other cell types (e.g., C8166).

In summary, we have demonstrated that viral DNA synthesis from vif− viruses produced from nonpermissive cells is abnormal in detergent-treated virions and in target cells. As NERT of vif− viruses can lead to plus-strand DNA and partially rescue intracellular reverse transcription and viral infectivity, the instability of the reverse transcription machinery in the target cells is likely responsible for the defect in reverse transcription. As such, dissecting the components and structure of intravirion and intracellular RT complexes of vif− viruses and the viral DNA molecular moieties of vif− viruses may lead to the further elucidation of the precise role(s) of Vif in the lentiviral life cycle.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Didier Trono and Mohamad Bouhamdan for helpful discussions and Rita M. Victor and Brenda O. Gordon for excellent secretarial assistance.

This work was supported by Thomas Jefferson University funds to H.Z. and by USPHS grant AI38666 to R.J.P.

REFERENCES

- 1.Best S, Le Tissier P, Towers G, Stoye J P. Positional cloning of the mouse retrovirus restriction gene Fv1. Nature. 1996;382:826–829. doi: 10.1038/382826a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blanc D, Patience C, Schulz T F, Weiss R, Spire B. Transcomplementation of VIF− HIV-1 mutants in CEM cells suggests that VIF affects late steps of the viral life cycle. Virology. 1993;193:186–192. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blomer U, Naldini L, Kafri T, Trono D, Verma I M, Gage F H. Highly efficient and sustained gene transfer in adult neurons with a lentivirus vector. J Virol. 1997;71:6641–6649. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.9.6641-6649.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boone L R, Glover P L, Innes C L, Niver L A, Bondurant M C, Yang W K. Fv-1 N- and B-tropism-specific sequences in murine leukemia virus and related endogenous proviral genomes. J Virol. 1988;62:2644–2650. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.8.2644-2650.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borman A M, Quillent C, Charneau P, Dauguet C, Clavel F. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vif− mutant particles from restrictive cells: role of Vif in correct particle assembly and infectivity. J Virol. 1995;69:2058–2067. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.4.2058-2067.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bouyac M, Rey F, Nascimbeni M, Courcoul M, Sire J, Blanc D, Clavel F, Vigne R, Spire B. Phenotypically Vif− human immunodeficiency virus type 1 is produced by chronically infected restrictive cells. J Virol. 1997;71:2473–2477. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.2473-2477.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bowerman B, Brown P O, Bishop J M, Varmus H E. A nucleoprotein complex mediates the integration of retroviral DNA. Genes Dev. 1989;3:469–478. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.4.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bukrinsky M I, Sharova N, McDonald T L, Pushkarskaya T, Tarpley W G, Stevenson M. Association of integrase, matrix, and reverse transcriptase antigens of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 with viral nucleic acids following acute infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:6125–6129. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.13.6125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Camaur D, Trono D. Characterization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vif particle incorporation. J Virol. 1996;70:6106–6111. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.9.6106-6111.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Charneau P, Alizon M, Clavel F. A second origin of DNA plus-strand synthesis is required for optimal human immunodeficiency virus replication. J Virol. 1992;66:2814–2820. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.5.2814-2820.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Courcoul M, Patience C, Rey F, Blanc D, Harmache A, Sire J, Vigne R, Spire B. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells produce normal amounts of defective Vif− human immunodeficiency virus type 1 particles which are restricted for the preretrotranscription steps. J Virol. 1995;69:2068–2074. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.4.2068-2074.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Darlix J L, Lapadat-Tapolsky M, de Rocquigny H, Roques B P. First glimpses at structure-function relationships of the nucleocapsid protein of retroviruses. J Mol Biol. 1995;254:523–537. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dettenhofer M, Yu X F. Highly purified human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reveals a virtual absence of Vif in virions. J Virol. 1999;73:1460–1467. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.2.1460-1467.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farnet C M, Haseltine W A. Determination of viral proteins present in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 preintegration complex. J Virol. 1991;65:1910–1915. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.4.1910-1915.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fisher A G, Ensoli B, Ivanoff L, Chamberlain M, Petteway S, Ratner L, Gallo R C, Wong-Staal F. The sor gene of HIV-1 is required for efficient virus transmission in vitro. Science. 1987;237:888–893. doi: 10.1126/science.3497453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fuentes G M, Palaniappan C, Fay P J, Bambara R A. Strand displacement synthesis in the central polypurine tract region of HIV-1 promotes DNA to DNA strand transfer recombination. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:29605–29611. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.47.29605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gabuzda D H, Lawrence K, Langhoff E, Terwilliger E, Dorfman T, Haseltine W A, Sodroski J. Role of vif in replication of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in CD4+ T lymphocytes. J Virol. 1992;66:6489–6495. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.11.6489-6495.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gabuzda D H, Li H, Lawrence K, Vasir B S, Crawford K, Langhoff E. Essential role of vif in establishing productive HIV-1 infection in peripheral blood T lymphocytes and monocyte/macrophages. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1994;7:908–915. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gallay P, Stitt V, Mundy C, Oettinger M, Trono D. Role of the karyopherin pathway in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nuclear import. J Virol. 1996;70:1027–1032. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.2.1027-1032.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gallay P, Swingler S, Song J, Bushman F, Trono D. HIV nuclear import is governed by the phosphotyrosine-mediated binding of matrix to the core domain of integrase. Cell. 1995;83:569–576. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90097-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gibbs J S, Regier D A, Desrosiers R C. Construction and in vitro properties of HIV-1 mutants with deletions in “nonessential” genes. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1994;10:343–350. doi: 10.1089/aid.1994.10.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goldman M J, Lee P S, Yang J S, Wilson J M. Lentiviral vectors for gene therapy of cystic fibrosis. Hum Gene Ther. 1997;8:2261–2268. doi: 10.1089/hum.1997.8.18-2261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goncalves J, Korin Y, Zack J, Gabuzda D. Role of Vif in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcription. J Virol. 1996;70:8701–8709. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.12.8701-8709.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoglund S, Ohagen A, Lawrence K, Gabuzda D. Role of vif during packing of the core of HIV-1. Virology. 1994;201:349–355. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hungnes O, Tjotta E, Grinde B. The plus strand is discontinuous in a subpopulation of unintegrated HIV-1 DNA. Arch Virol. 1991;116:133–141. doi: 10.1007/BF01319237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kafri T, Blomer U, Peterson D A, Gage F H, Verma I M. Sustained expression of genes delivered directly into liver and muscle by lentiviral vectors. Nat Genet. 1997;17:314–317. doi: 10.1038/ng1197-314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kimpton J, Emerman M. Detection of replication-competent and pseudotyped human immunodeficiency virus with a sensitive cell line on the basis of activation of an integrated β-galactosidase gene. J Virol. 1992;66:2232–2239. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.4.2232-2239.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kulkosky J, BouHamdan M, Geist A, Pomerantz R J. A novel Vpr peptide interactor fused to integrase (IN) restores integration activity to IN-defective HIV-1 virions. Virology. 1999;255:77–85. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lapadat-Tapolsky M, Gabus C, Rau M, Darlix J L. Possible roles of HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein in the specificity of proviral DNA synthesis and in its variability. J Mol Biol. 1997;268:250–260. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.0978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lener D, Tanchou V, Roques B P, Le Grice S F, Darlix J L. Involvement of HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein in the recruitment of reverse transcriptase into nucleoprotein complexes formed in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:33781–33786. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.50.33781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levy-Mintz P, Duan L, Zhang H, Hu B, Dornadula G, Zhu M, Kulkosky J, Bizub-Bender D, Skalka A M, Pomerantz R J. Intracellular expression of single-chain variable fragments to inhibit early stages of the viral life cycle by targeting human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase. J Virol. 1996;70:8821–8832. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.12.8821-8832.1996. . (Erratum, 72:3505–3506, 1998.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Research Misconduct Found]

- 32.Madani N, Kabat D. An endogenous inhibitor of human immunodeficiency virus in human lymphocytes is overcome by the viral Vif protein. J Virol. 1998;72:10251–10255. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.12.10251-10255.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miller M D, Farnet C M, Bushman F D. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 preintegration complexes: studies of organization and composition. J Virol. 1997;71:5382–5390. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.7.5382-5390.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miller M D, Wang B, Bushman F D. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 preintegration complexes containing discontinuous plus strands are competent to integrate in vitro. J Virol. 1995;69:3938–3944. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.6.3938-3944.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Naldini L, Blomer U, Gage F H, Trono D, Verma I M. Efficient transfer, integration, and sustained long-term expression of the transgene in adult rat brains injected with a lentiviral vector. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11382–11388. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Negroni M, Buc H. Recombination during reverse transcription: an evaluation of the role of the nucleocapsid protein. J Mol Biol. 1999;286:15–31. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ou C Y, Boone L R, Koh C K, Tennant R W, Yang W K. Nucleotide sequences of gag-pol regions that determine the Fv-1 host range property of BALB/c N-tropic and B-tropic murine leukemia viruses. J Virol. 1983;48:779–784. doi: 10.1128/jvi.48.3.779-784.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pauza C D, Trivedi P, McKechnie T S, Richman D D, Graziano F M. 2-LTR circular viral DNA as a marker for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection in vivo. Virology. 1994;205:470–478. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sakai H, Shibata R, Sakuragi J, Sakuragi S, Kawamura M, Adachi A. Cell-dependent requirement of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vif protein for maturation of virus particles. J Virol. 1993;67:1663–1666. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.3.1663-1666.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Simon J H, Gaddis N C, Fouchier R A, Malim M H. Evidence for a newly discovered cellular anti-HIV-1 phenotype. Nat Med. 1998;4:1397–1400. doi: 10.1038/3987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40a.Simon J H, Southerling T E, Peterson J C, Meyer B E, Malim M H. Complementation of vif-defective human immunodeficiency virus type 1 by primate, but not nonprimate, lentivirus vif genes. J Virol. 1995;69:4166–4172. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.7.4166-4172.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Simon J H, Malim M H. The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vif protein modulates the postpenetration stability of viral nucleoprotein complexes. J Virol. 1996;70:5297–5305. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.8.5297-5305.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Simon J H, Miller D L, Fouchier R A, Malim M H. Virion incorporation of human immunodeficiency virus type-1 Vif is determined by intracellular expression level and may not be necessary for function. Virology. 1998;248:182–187. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sova P, Volsky D J. Efficiency of viral DNA synthesis during infection of permissive and nonpermissive cells with vif-negative human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1993;67:6322–6326. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.10.6322-6326.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Strebel K, Daugherty D, Clouse K, Cohen D, Folks T, Martin M A. The HIV 'A' (sor) gene product is essential for virus infectivity. Nature. 1987;328:728–730. doi: 10.1038/328728a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tanchou V, Decimo D, Pechoux C, Lener D, Rogemond V, Berthoux L, Ottmann M, Darlix J L. Role of the N-terminal zinc finger of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nucleocapsid protein in virus structure and replication. J Virol. 1998;72:4442–4447. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.4442-4447.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Taswell C. Limiting dilution assays for the determination of immunocompetent cell frequencies. I. Data analysis. J Immunol. 1981;126:1614–1619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.von Schwedler U, Song J, Aiken C, Trono D. vif is crucial for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 proviral DNA synthesis in infected cells. J Virol. 1993;67:4945–4955. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.8.4945-4955.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang H, Bagasra O, Niikura M, Poiesz B J, Pomerantz R J. Intravirion reverse transcripts in the peripheral blood plasma of human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected individuals. J Virol. 1994;68:7591–7597. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.11.7591-7597.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang H, Dornadula G, Alur P, Laughlin M A, Pomerantz R J. Amphipathic domains in the C terminus of the transmembrane protein (gp41) permeabilize HIV-1 virions: a molecular mechanism underlying natural endogenous reverse transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:12519–12524. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.22.12519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang, H., G. Dornadula, M. Beumont, L. Livornese, Jr., B. Van Uitert, K. Henning, and R. J. Pomerantz. 1998. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in the semen of men receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 339:1803–1809. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Zhang H, Dornadula G, Pomerantz R J. Endogenous reverse transcription of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in physiological microenvironments: an important stage for viral infection of nondividing cells. J Virol. 1996;70:2809–2824. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.5.2809-2824.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang H, Dornadula G, Wu Y, Havlir D, Richman D D, Pomerantz R J. Kinetic analysis of intravirion reverse transcription in the blood plasma of human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected individuals: direct assessment of resistance to reverse transcriptase inhibitors in vivo. J Virol. 1996;70:628–634. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.1.628-634.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang H, Zhang Y, Spicer T P, Abbott L Z, Abbott M, Poiesz B J. Reverse transcription takes place within extracellular HIV-1 virions: potential biological significance. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1993;9:1287–1296. doi: 10.1089/aid.1993.9.1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]