Abstract

Background: Breastfeeding could improve a child’s health early on, but its long-term effects on childhood behavioral and emotional development remain inconclusive. We aimed to estimate the associations of feeding practice with childhood behavioral and emotional development. Methods: In this population-based birth cohort study, data on feeding patterns for the first 6 mo of life, the duration of breastfeeding, and children’s emotional and behavioral outcomes were prospectively collected from 2489 mother–child dyads. Feeding patterns for the first 6 mo included exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) and non-exclusive breastfeeding (non-EBF, including mixed feeding or formula feeding), and the duration of breastfeeding (EBF or mixed feeding) was categorized into ≤6 mo, 7–12 mo, 13–18 mo, and >18 mo. Externalizing problems and internalizing problems were assessed with the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) and operationalized according to recommended clinical cutoffs, corresponding to T scores ≥64. Multivariable linear regression and logistic regression were used to evaluate the association of feeding practice with CBCL outcomes. Results: The median (interquartile range) age of children at the outcome measurement was 32.0 (17.0) mo. Compared with non-EBF for the first 6 mo, EBF was associated with a lower T score of internalizing problems [adjusted mean difference (aMD): −1.31; 95% confidence interval (95% CI): −2.53, −0.10], and it was marginally associated with T scores of externalizing problems (aMD: −0.88; 95% CI: −1.92, 0.15). When dichotomized, EBF versus non-EBF was associated with a lower risk of externalizing problems (aOR: 0.54, 95% CI: 0.34, 0.87), and it was marginally associated with internalizing problems (aOR: 0.75, 95% CI: 0.54, 1.06). Regarding the duration of breastfeeding, breastfeeding for 13–18 mo versus ≤6 mo was associated with lower T scores of internalizing problems (aMD: −2.50; 95% CI: −4.43, −0.56) and externalizing problems (aMD: −2.75; 95% CI: −4.40, −1.10), and breastfeeding for >18 mo versus ≤6 mo was associated with lower T scores of externalizing problems (aMD: −1.88; 95% CI: −3.68, −0.08). When dichotomized, breastfeeding for periods of 7–12 mo, 13–18 mo, and >18 mo was associated with lower risks of externalizing problems [aOR (95% CI): 0.96 (0.92, 0.99), 0.94 (0.91, 0.98), 0.96 (0.92, 0.99), respectively]. Conclusions: Exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 mo and a longer duration of breastfeeding, exclusively or partially, are beneficial for childhood behavioral and emotional development.

Keywords: breastfeeding, behavioral outcomes, emotional outcomes, children, cohort study

1. Introduction

Childhood behavioral and emotional development is a public health concern [1] since its dysregulations could increase the risk of developing mental health problems during adulthood [2,3]. Behavioral and emotional dysregulation among school-aged children has an average multinational prevalence of 9% (range, 2−18%; n = 56,666) [4]. Approximately 10% of American children younger than 5 y experienced clinically significant emotional and behavioral problems [5], and the corresponding prevalence among school-aged children was 15.9% in China [6]. Behavioral and emotional development is influenced by various biological, social, and environmental factors [7,8,9]. Identifying modifiable factors in early life provides opportunities for early intervention and the prevention of behavioral and emotional problems.

The feeding practices of infants may be among the potential modifiable factors for behavioral and emotional problems. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) for the first 6 months (mo) of life, with the introduction of appropriate complementary foods thereafter and continued breastfeeding up to 2 y of age or beyond [10]. Attributed to the abundant vital nutrients in breastmilk [11] and mother–infant interaction during breastfeeding [12], breastfeeding confers a wide range of benefits for infants [13], such as lower risks of asthma, obesity, diabetes, and leukemia in later life [14]. Accumulating evidence suggests that the feeding practices of infants may affect offspring’s cognitive performance. A meta-analysis of 17 studies showed that breastfeeding was related to an improved intelligence quotient (IQ) among children and adolescents [15]. Although the association between breastfeeding and children’s IQs has been well studied, studies on breastfeeding and offspring’s behavioral and emotional development are limited.

There are only two studies that have assessed the associations of EBF with offspring behavioral and emotional development. A cohort study involving American children showed that ≥3 mo of EBF combined with ≥6 mo of breastfeeding was associated with better emotional and conduct performance at 6 y old compared to children who were never breastfed [16]. The other cohort study, involving Chinese children, found a modest but significant lower score of emotional problems at 5 y old in those who underwent EBF versus non-EBF, whereas no results were reported for behavioral problems [17]. Several studies were conducted to explore the effect of breastfeeding duration on offspring behavioral and emotional development but reported inconsistent results. Some found that a longer duration of breastfeeding was associated with better childhood behavioral and emotional development [18,19,20,21,22], whereas others did not find significant associations [16,23]. In addition, these studies focused on breastfeeding within the first 12 mo of life, and little is known about breastfeeding duration up to 1–2 y of age, as recommended by the WHO. Furthermore, all of these studies treated breastfeeding duration as a categorical variable, and few have explored its relationship as a continuous variable with behavioral and emotional development. Most studies were restricted to a Caucasian population, and the data are sparse for Asian populations, especially Chinese populations [24,25].

The objective of this study was to estimate the associations of EBF as well as a duration of breastfeeding prolonged to >18 mo with childhood behavioral and emotional development using data from a large prospective cohort study in China. Simultaneously, we tried to explore whether the associations varied based on children’s sex.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Study Design

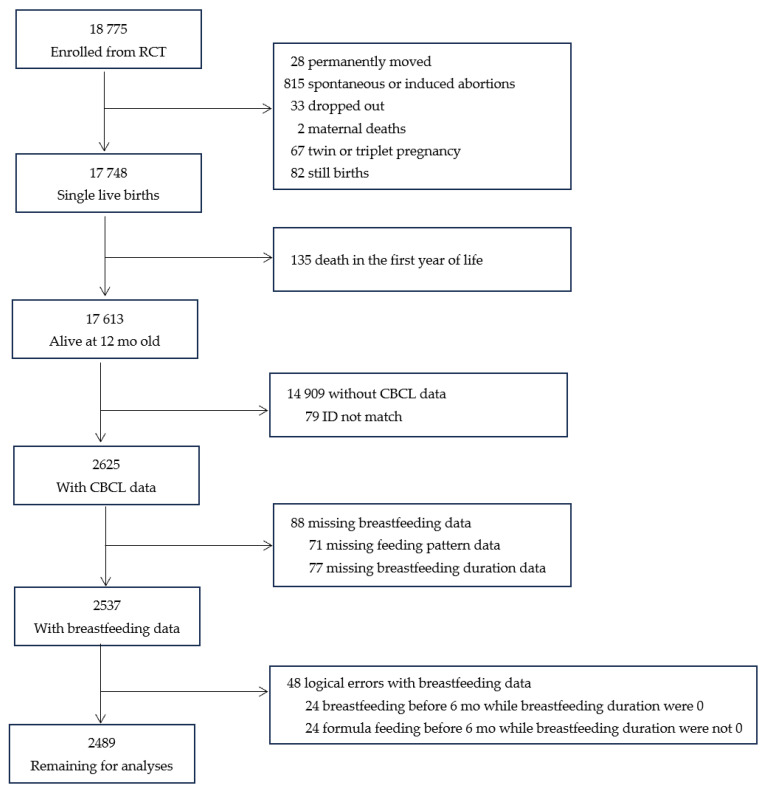

This prospective cohort study was conducted based on a randomized controlled trial (RCT) implemented from May 2006 to April 2009 in Hebei Province, China. The details of the RCT have been provided elsewhere [26]. In brief, 18,775 singleton nulliparous women in early pregnancy were enrolled and randomly assigned to receive folic acid, iron–folic acid, or multiple micronutrients daily until delivery, and their infants were followed up with until 12 mo after birth. Among the 17,613 infants alive at 12 mo old, 2715 children were randomly selected to participate in a follow-up program conducted from May to August in 2011 when they were 18–60 mo old. In this follow-up program, information on duration of breastfeeding and children’s emotional and behavioral development was collected. In this study, we excluded 136 children who had incomplete (n = 88) or incorrect (n = 48) information on feeding practice, leaving 2489 children in the final analysis (Figure 1). Maternal and children characteristics were comparable between the included (n = 2489) and excluded children (n = 15,124). (Table A1).

Figure 1.

Participant flow chart.

Both the RCT and the follow-up study were approved by the Peking University Health Science Center Institutional Review Board with identifiers of NCT00133744 and NCT01404416 on Clinicaltrials.gov, respectively. All caregivers of the participants provided written informed consent.

2.2. Exposure, Outcomes, and Covariates

The exposure variables for the present study were the feeding pattern for the first 6 mo of life and the duration of breastfeeding until the follow-up in 2011. The feeding patterns for the first 6 mo were extracted from the RCT dataset and were categorized as EBF, formula feeding, or mixed feeding. EBF was defined as breastfeeding only without other liquids or solid food [27]. Due to the limited numbers of formula feeding and mixed feeding, they were combined in the non-EBF group in the analysis below. Duration of breastfeeding (EBF and mixed feeding) was used as a continuous variable and a categorical variable, as detailed in the following statistical analysis.

The outcomes, including a range of behavioral and emotional problems, were assessed using a validated Chinese version of the Child Behavior Checklist for ages in the range of 1.5–5.0 y (CBCL 1.5–5.0) [28]. The CBCL, completed by caregivers under the guidance of trained doctors, consists of 99 closed items describing behaviors exhibited by the child during the preceding 2 mo. Each closed item scored 0 (not true), 1 (somewhat or sometimes true), or 2 points (very true or often true). Subscores were calculated for (1) seven syndromes, including emotionally reactive, anxiety/depression, somatic complaints, withdrawn behavior, sleep problems, attention problems, and aggressive behavior; (2) three composite problem scales: emotional or internalizing problems (emotionally reactive, anxious/depressed, somatic complaints, and withdrawn behavior), behavioral or externalizing problems (attention problems and aggressive behavior), and total problems; (3) five scales were oriented to the following Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th edition) (DSM-V) categories: affective problems, anxiety problems, pervasive developmental problems, attention deficit/hyperactivity problems, and oppositional defiant problems. A normalized T score was assigned for each scale according to a normative sample [28]. The behavioral and emotional problems were operationalized according to recommended clinical cutoffs, corresponding to T scores ≥64 for the three composite problems and T scores ≥70 for seven syndromes and five DSM-V-oriented problems.

Most covariates were extracted from the RCT database, including maternal age at delivery (y), gestational age (week, wk), education (primary school, middle school, or high school or above), occupation (farmer or others), height, weight in early pregnancy, anemia in mid-pregnancy (hemoglobin concentration <110 g/L [29]), supplementation during pregnancy (folic acid, iron–folic acid, or multiple micronutrients), delivery mode (vaginal delivery or cesarean delivery), children’s sex (boy or girl), and birthweight (g). Maternal body mass index (BMI) was calculated as the maternal weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared and categorized as <18.5, 18.5–22.9, 23.0–27.4, or ≥27.5 kg/m2 according to criteria for Asians [30]. Information on the main caregivers of the child (parents or grandparents), kindergarten attendance (yes or no), and child’s age at follow-up (mo) were collected in the follow-up program.

2.3. Statistical Analyses

Continuous variables were presented using the mean (standard deviation, SD) or median (interquartile range, IQR) depending on the distribution’s normality assessed by the Shapiro–Wilk test. Categorical variables were presented using frequency (%). Differences between groups of feeding patterns for the first 6 mo of life (EBF and non-EBF) were analyzed by Welch t-test for means since the Bartlett test indicated variance heterogeneity between groups, Mann–Whitney test for medians, and chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test for frequencies.

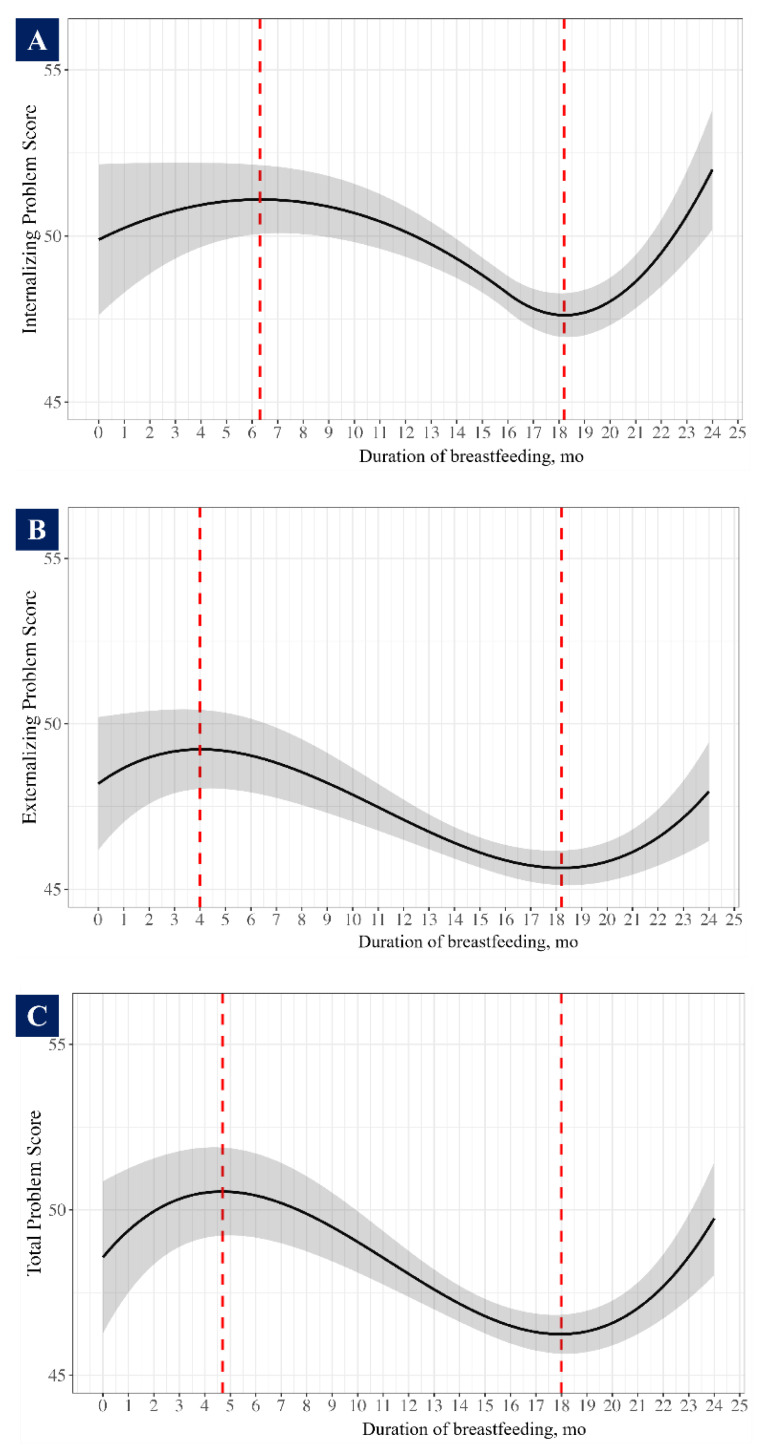

Duration of breastfeeding was first used as a continuous variable in multivariable restricted cubic spline (RCS) models to explore its linear or non-linear relationship with T scores of behavioral and emotional problems. If a non-linear relationship was observed, a 10-fold cross-validation approach was used to identify the optimal degree of freedom that yielded the highest R-squared value. Then, the inflection points of the constructed curves were determined (Figure A1). On the basis of the inflection points and to make comparisons with previous studies, the duration of breastfeeding was categorized as ≤6 mo, 7–12 mo, 13–18 mo, and >18 mo in the following analysis.

Univariable and multivariable linear regression models were used to calculate the crude mean differences (cMDs) and adjusted mean differences (aMDs) in T scores across different groups of feeding patterns for the first 6 mo and on the duration of breastfeeding. Univariable and multivariable logistic regression models were used to estimate the crude odds ratios (cORs) and adjusted odds ratios (aORs) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) for behavioral and emotional problems. In multivariable analyses, we adjusted for maternal age, gestational age, education, occupation, BMI in early pregnancy, anemia in mid-pregnancy, supplementation during pregnancy, delivery mode, children’s sex, birthweight, main caregiver, kindergarten attendance, and child’s age at outcome measurement.

Because the emotional and behavioral development of children differs based on their sex [31], we performed a subgroup analysis stratified by children’s sex (boys and girls) and evaluated whether the associations varied by children’s sex by adding an interaction term into the multivariable regression models.

All p-values were 2-sided, and statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. All analyses were conducted using R software (version 4.2.3).

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

The median (IQR) maternal age at delivery was 22.7 (3.0) years. A total of 98.8% of the mothers were of Han ethnicity, 99.0% possessed middle school education or above, and 93.5% were farmers. The median (IQR) age of the children at the outcome measurement was 32.0 (17.0) mo. Of the 2489 children, 51.8% were boys, 83.8% underwent EBF for the first 6 mo of life, and their median (IQR) duration of breastfeeding was 16.0 (6.0) mo. The maternal and children characteristics, according to the feeding patterns for the first 6 mo of life, are presented in Table 1. Compared with children who underwent EBF, non-EBF children were more likely to be boys (50.7% vs. 57.4%), to be taken care of by their grandparents (17.8% vs. 34.4%), and to have attended kindergarten (25.3% vs. 30.4%).

Table 1.

Maternal and children characteristics according to feeding patterns for first 6 mo of life.

| Characteristics | Overall | Non-EBF | EBF | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 2489) | (N = 404) | (N = 2085) | ||

| Maternal | ||||

| Age at delivery, y, median (IQR) | 22.7 (3.0) | 22.6 (2.9) | 22.7 (3.1) | 0.081 |

| Gestational age, wk, mean (SD) | 39.7 (1.6) | 39.6 (1.7) | 39.7 (1.5) | 0.165 |

| Ethnicity, no. (%) | 0.624 | |||

| Han | 2458 (98.8) | 398 (98.5) | 2060 (98.8) | |

| Other | 31 (1.2) | 6 (1.5) | 25 (1.2) | |

| Education, no. (%) | 0.116 | |||

| ≥High school | 397 (16.0) | 78 (19.3) | 319 (15.3) | |

| Middle school | 2066 (83.0) | 321 (79.5) | 1745 (83.7) | |

| ≤Primary school | 26 (1.0) | 5 (1.2) | 21 (1.0) | |

| Occupation, no. (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Farmer | 2327 (93.5) | 358 (88.6) | 1969 (94.4) | |

| Other | 162 (6.5) | 46 (11.4) | 116 (5.6) | |

| BMI in early pregnancy, kg/m2, no. (%) | 0.014 | |||

| <18.5 | 207 (8.3) | 49 (12.1) | 158 (7.6) | |

| 18.5–22.9 | 1562 (62.8) | 237 (58.7) | 1325 (63.5) | |

| 23.0–27.4 | 612 (24.6) | 97 (24.0) | 515 (24.7) | |

| ≥27.5 | 108 (4.3) | 21 (5.2) | 87 (4.2) | |

| Anemia in mid-pregnancy, no. (%) | 0.359 | |||

| No | 2329 (93.6) | 372 (92.1) | 1957 (93.9) | |

| Yes | 149 (6.0) | 28 (6.9) | 121 (5.8) | |

| Missing | 11(0.4) | 4(1.0) | 7(0.3) | |

| Supplementation during pregnancy, no. (%) | 0.937 | |||

| Folic acid | 812 (32.6) | 129 (31.9) | 683 (32.8) | |

| Iron–folic acid | 855 (34.4) | 139 (34.4) | 716 (34.3) | |

| Multiple micronutrients | 822 (33.0) | 136 (33.7) | 686 (32.9) | |

| Delivery mode, no. (%) | 0.624 | |||

| Vaginal delivery | 1300 (52.2) | 216 (53.5) | 1084 (52.0) | |

| Cesarean delivery | 1188 (47.7) | 188 (46.5) | 1000 (48.0) | |

| Missing | 1(0.0) | 0(0) | 1(0.0) | |

| Children | ||||

| Sex, no. (%) | 0.014 | |||

| Male | 1290 (51.8) | 232 (57.4) | 1058 (50.7) | |

| Female | 1199 (48.2) | 172 (42.6) | 1027 (49.3) | |

| Birthweight, no. (%) | 0.354 | |||

| <2500 | 43 (1.7) | 9 (2.2) | 34 (1.6) | |

| 2500–3999 | 2337 (93.9) | 373 (92.3) | 1964 (94.2) | |

| ≥4000 | 109 (4.4) | 22 (5.4) | 87 (4.2) | |

| Age at follow-up, mo, median (IQR) | 32.0 (17.0) | 31.0 (14.1) | 32.0 (17.0) | 0.172 |

| Age at follow-up, mo, no. (%) | 0.051 | |||

| 18–29 | 1102 (44.3) | 178 (44.1) | 924 (44.3) | |

| 30–35 | 437 (17.6) | 90 (22.3) | 347 (16.6) | |

| 36–41 | 280 (11.2) | 44 (10.9) | 236 (11.3) | |

| 42–47 | 400 (16.1) | 53 (13.1) | 347 (16.6) | |

| 48–60 | 270 (10.8) | 39 (9.7) | 231 (11.1) | |

| Main caregivers, no. (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Parents | 1975 (79.3) | 265 (65.6) | 1710 (82.0) | |

| Grandparents | 510 (20.5) | 139 (34.4) | 371 (17.8) | |

| Missing | 4 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 4 (0.2) | |

| Kindergarten attendance, no. (%) | 0.035 | |||

| Yes | 1835 (73.7) | 281 (69.6) | 1554 (74.5) | |

| No | 650 (26.1) | 123 (30.4) | 527 (25.3) | |

| Missing | 4 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 4 (0.2) |

3.2. Feeding Patterns for the First 6 mo and Behavioral and Emotional Development

According to a univariable analysis, EBF children versus non-EBF children had statistically significant lower T scores of internalizing problems (cMD: −1.39; 95% CI: −2.59, −0.20), externalizing problems (cMD: −1.33; 95% CI: −2.36, −0.30), and total problems (cMD: −1.54; 95% CI: −2.71, −0.37) (Table 2). After a multivariable adjustment, the EBF children had significantly lower T scores of internalizing problems (aMD: −1.31; 95% CI: −2.53, −0.10) and total problems (aMD: −1.26; 95% CI: −2.44, −0.08) and marginally higher T scores of externalizing problems (aMD: −0.88; 95% CI: −1.92, 0.15). EBF was associated with lower T scores regarding somatic complaints (aMD: −1.26; 95% CI: −1.93, −0.59), aggressive behavior (aMD: −0.57; 95% CI: −1.08, −0.06), and DSM-V-oriented anxiety problems (aMD: −0.79; 95% CI: −1.47, −0.10). Multivariable logistic regression models showed that EBF was associated with lower risks of externalizing problems (aOR: 0.54; 95% CI: 0.34, 0.87), and it was marginally associated with lower risks of internalizing problems (aOR: 0.75; 95% CI: 0.54, 1.06) and total problems (aOR: 0.69; 95% CI: 0.47, 1.01), as well as with DSM-V-oriented attention deficit/hyperactivity problems (aOR: 0.35; 95% CI: 0.18, 0.69) (Table 3). No other behavioral or emotional scales were significantly associated with feeding patterns.

Table 2.

Mean differences in T scores for child behavioral and emotional problems based on feeding patterns for first 6 mo of life; mean (SD).

| Items | Non-EBF (n = 404) |

EBF (n = 2085) |

cMD (95% CI) | p | aMD (95% CI) * | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Syndrome | ||||||

| Emotionally reactive | 54.4 (5.78) | 53.9 (5.71) | −0.48 (−1.09, 0.13) | 0.124 | −0.49 (−1.11, 0.14) | 0.126 |

| Anxious/depressed | 53.6 (5.35) | 53.3 (5.49) | −0.35 (−0.93, 0.23) | 0.241 | −0.46 (−1.06, 0.13) | 0.126 |

| Somatic complaints | 55.2 (6.67) | 53.9 (6.07) | −1.25 (−1.91, −0.60) | <0.001 | −1.26 (−1.93, −0.59) | <0.001 |

| Withdrawn behavior | 55.7 (6.47) | 55.2 (6.69) | −0.50 (−1.21, 0.21) | 0.166 | −0.37 (−1.09, 0.36) | 0.320 |

| Sleep problems | 52.3 (3.94) | 52.2 (3.92) | −0.13 (−0.55, 0.29) | 0.536 | −0.14 (−0.57, 0.28) | 0.511 |

| Attention problems | 53.8 (5.19) | 53.2 (4.79) | −0.53 (−1.05, −0.01) | 0.045 | −0.26 (−0.79, 0.26) | 0.324 |

| Aggressive behavior | 53.0 (5.17) | 52.3 (4.63) | −0.74 (−1.24, −0.23) | 0.004 | −0.57 (−1.08, −0.06) | 0.030 |

| Stress problems | 53.8 (5.64) | 53.3 (5.53) | −0.47 (−1.06, 0.12) | 0.121 | −0.48 (−1.08, 0.13) | 0.122 |

| Composite problem | ||||||

| Internalizing problems | 50.1 (11.4) | 48.7 (11.2) | −1.39 (−2.59, −0.20) | 0.022 | −1.31 (−2.53, −0.10) | 0.034 |

| Externalizing problems | 47.6 (10.1) | 46.3 (9.56) | −1.33 (−2.36, −0.30) | 0.011 | −0.88 (−1.92, 0.15) | 0.094 |

| Total problems | 48.6 (11.5) | 47.0 (10.9) | −1.54 (−2.71, −0.37) | 0.010 | −1.26 (−2.44, −0.08) | 0.037 |

| DSM-oriented problem | ||||||

| Affective problems | 55.6 (6.96) | 55.1 (6.60) | −0.53 (−1.24, 0.18) | 0.140 | −0.54 (−1.26, 0.18) | 0.142 |

| Anxiety problems | 54.9 (6.85) | 54.2 (6.17) | −0.66 (−1.33, 0.01) | 0.053 | −0.79 (−1.47, −0.10) | 0.024 |

| Pervasive developmental problems | 55.6 (6.92) | 55.1 (7.07) | −0.49 (−1.24, 0.26) | 0.204 | −0.38 (−1.14, 0.39) | 0.336 |

| Attention deficit/hyperactivity problems | 54.1 (5.63) | 53.4 (5.03) | −0.69 (−1.23, −0.14) | 0.014 | −0.45 (−1.00, 0.11) | 0.114 |

| Oppositional defiant problems | 52.4 (4.35) | 52.0 (4.12) | −0.46 (−0.90, −0.02) | 0.042 | −0.34 (−0.79, 0.11) | 0.141 |

Notes: * Adjusted for maternal age, gestational week, education, occupation, BMI in early pregnancy, anemia in mid-pregnancy, supplementation during pregnancy, delivery mode, children’s sex, age, birthweight, main caregiver, and kindergarten attendance.

Table 3.

Risks of childhood behavioral and emotional problems based on feeding patterns for first 6 mo of life.

| Items | Non-EBF (n = 404) |

EBF (n = 2085) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Events (%) | Events (%) | cOR (95% CI) | p | aOR (95% CI) * | p | |

| Syndrome | ||||||

| Emotionally reactive | 5 (1.2) | 25 (1.2) | 0.97 (0.37, 2.54) | 0.948 | 0.87 (0.32, 2.34) | 0.785 |

| Anxious/depressed | 6 (1.5) | 37 (1.8) | 1.20 (0.50, 2.86) | 0.683 | 1.12 (0.46, 2.72) | 0.802 |

| Somatic complaints | 19 (4.7) | 66 (3.2) | 0.66 (0.39, 1.12) | 0.122 | 0.67 (0.39, 1.15) | 0.144 |

| Withdrawn behavior | 20 (5.0) | 103 (4.9) | 1.00 (0.61, 1.63) | 0.993 | 1.04 (0.63, 1.72) | 0.889 |

| Sleep problems | 2 (0.5) | 14 (0.7) | 1.36 (0.31, 6.00) | 0.686 | 1.29 (0.28, 5.90) | 0.741 |

| Attention problems | 8 (2.0) | 35 (1.7) | 0.85 (0.39, 1.84) | 0.671 | 0.95 (0.43, 2.10) | 0.891 |

| Aggressive behavior | 3 (0.7) | 21 (1.0) | 1.36 (0.40, 4.58) | 0.620 | 1.51 (0.43, 5.28) | 0.521 |

| Stress problems | 11 (2.7) | 63 (3.0) | 1.11 (0.58, 2.13) | 0.746 | 1.11 (0.57, 2.16) | 0.752 |

| Composite problem | ||||||

| Internalizing problems | 49 (12.1) | 200 (9.6) | 0.77 (0.55, 1.07) | 0.121 | 0.75 (0.54, 1.06) | 0.106 |

| Externalizing problems | 27 (6.7) | 72 (3.5) | 0.50 (0.32, 0.79) | 0.003 | 0.54 (0.34, 0.87) | 0.011 |

| Total problems | 41 (10.1) | 147 (7.1) | 0.67 (0.47, 0.97) | 0.032 | 0.69 (0.47, 1.01) | 0.056 |

| DSM-oriented problem | ||||||

| Affective problems | 29 (7.2) | 122 (5.9) | 0.80 (0.53, 1.22) | 0.307 | 0.77 (0.50, 1.18) | 0.230 |

| Anxiety problems | 21 (5.2) | 83 (4.0) | 0.76 (0.46, 1.24) | 0.265 | 0.70 (0.42, 1.16) | 0.164 |

| Pervasive developmental problems | 27 (6.7) | 129 (6.2) | 0.92 (0.60, 1.41) | 0.707 | 0.89 (0.58, 1.39) | 0.620 |

| Attention deficit/hyperactivity problems | 15 (3.7) | 26 (1.2) | 0.33 (0.17, 0.62) | 0.001 | 0.35 (0.18, 0.69) | 0.002 |

| Oppositional defiant problems | 5 (1.2) | 36 (1.7) | 1.40 (0.55, 3.59) | 0.482 | 1.64 (0.62, 4.30) | 0.317 |

Notes: * Adjusted for maternal age, gestational week, education, occupation, BMI in early pregnancy, anemia in mid-pregnancy, supplementation during pregnancy, delivery mode, children’s sex, age, birthweight, main caregiver, and kindergarten attendance.

3.3. Duration of Breastfeeding and Behavioral and Emotional Development

Non-linear relationships were exhibited between breastfeeding duration continuum and T scores of internalizing problems, externalizing problems, and total problems. The shapes of their curves were similar, with consistent inflections at around 6 mo and 18 mo. The T scores significantly decreased during the 6–18 mo period, but not for ≤6 mo or >18 mo (Table A2).

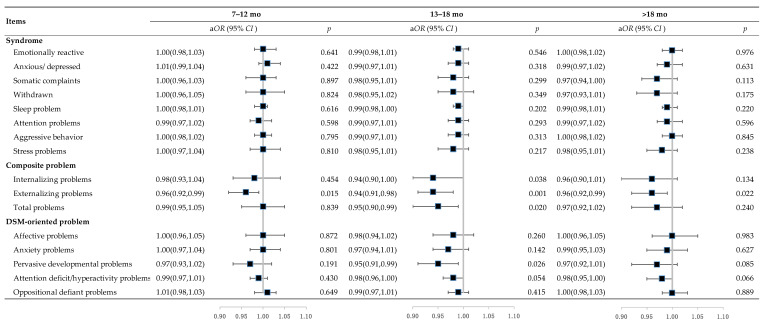

Analyses of breastfeeding duration categories showed that, compared with children who were breastfed for ≤6 mo, those who were breastfed for 7–12 mo had no significant differences in behavioral or emotional T scores, whereas those who were breastfed for 13–18 mo had significantly lower T scores of internalizing problems (aMD: −2.50; 95% CI: −4.43, −0.56), externalizing problems (aMD: −2.75; 95% CI: −4.40, −1.10), and total problems (aMD: −2.96; 95% CI: −4.84, −1.07), and those who were breastfed for >18 mo had lower T scores of externalizing problems (aMD: −1.88; 95% CI: −3.68, −0.08) (Table 4). In addition, children who were breastfed for 13–18 mo had lower T scores of emotionally reactive behavior, somatic complaints, attention problems, aggressive behavior, as well as DSM-V-oriented pervasive developmental problems, attention deficit/hyperactivity problems, and oppositional defiant problems (Table 4). Multivariable logistic regression models showed that breastfeeding for periods of 7–12 mo, 13–18 mo, and >18 mo was associated with lower risks of externalizing problems [aOR (95% CI): 0.96 (0.92, 0.99), 0.94 (0.91, 0.98), 0.96 (0.92, 0.99), respectively], and breastfeeding for 13–18 mo was associated with a lower risk of total problems (aOR: 0.95, 95% CI: 0.90, 0.99) compared with breastfeeding for ≤6 mo (Figure 2). No other behavioral or emotional scales were significantly associated with the duration of breastfeeding.

Table 4.

Mean differences of T scores for child behavioral and emotional problems based on duration of breastfeeding.

| Items | 7–12 mo (n = 489) | 13–18 mo (n = 1408) | >18 mo (n = 450) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cMD (95% CI) | p | aMD (95% CI) * | p | cMD (95% CI) | p | aMD (95% CI) * | p | cMD (95% CI) | p | aMD (95% CI) * | p | |

| Syndrome | ||||||||||||

| Emotionally reactive | −0.47 (−1.54, 0.59) | 0.385 | −0.33 (−1.40, 0.74) | 0.550 | −1.29 (−2.28, −0.31) | 0.010 | −1.22 (−2.22, −0.23) | 0.016 | −0.82 (−1.89, 0.26) | 0.138 | −0.79 (−1.88, 0.29) | 0.152 |

| Anxious/depressed | 0.24 (−0.78, 1.25) | 0.650 | 0.32 (−0.70, 1.34) | 0.537 | −0.84 (−1.78, 0.10) | 0.079 | −0.92 (−1.87, 0.03) | 0.058 | −0.44 (−1.47, 0.59) | 0.398 | −0.53 (−1.57, 0.51) | 0.317 |

| Somatic complaints | 0.07 (−1.08, 1.22) | 0.907 | 0.13 (−1.03, 1.28) | 0.832 | −1.05 (−2.12, 0.01) | 0.053 | −1.08 (−2.16, −0.01) | 0.048 | −0.84 (−2.01, 0.32) | 0.157 | −0.88 (−2.05, 0.30) | 0.144 |

| Withdrawn behavior | 0.11 (−1.13, 1.35) | 0.861 | 0.24 (−1.00, 1.49) | 0.703 | −1.05 (−2.20, 0.10) | 0.073 | −0.88 (−2.03, 0.28) | 0.138 | −0.42 (−1.67, 0.84) | 0.515 | −0.27 (−1.53, 0.99) | 0.674 |

| Sleep problems | 0.08 (−0.65, 0.82) | 0.821 | 0.18 (−0.55, 0.92) | 0.629 | −0.15 (−0.83, 0.52) | 0.658 | −0.12 (−0.80, 0.56) | 0.726 | −0.03 (−0.77, 0.71) | 0.943 | −0.01 (−0.76, 0.73) | 0.976 |

| Attention problems | −0.53 (−1.44, 0.37) | 0.249 | −0.37 (−1.27, 0.53) | 0.423 | −1.27 (−2.11, −0.44) | 0.003 | −1.01 (−1.85, −0.18) | 0.017 | −0.97 (−1.88, −0.05) | 0.038 | −0.78 (−1.69, 0.13) | 0.095 |

| Aggressive behavior | −0.71 (−1.59, 0.17) | 0.113 | −0.53 (−1.41, 0.35) | 0.238 | −1.60 (−2.41, −0.79) | <0.001 | −1.42 (−2.23, −0.60) | 0.001 | −1.19 (−2.08, −0.30) | 0.009 | −1.05 (−1.94, −0.16) | 0.021 |

| Stress problems | 0.30 (−0.74, 1.33) | 0.573 | 0.34 (−0.70, 1.38) | 0.523 | −0.62 (−1.57, 0.34) | 0.205 | −0.62 (−1.58, 0.35) | 0.210 | −0.42 (−1.47, 0.62) | 0.426 | −0.48 (−1.53, 0.58) | 0.377 |

| Composite problem | ||||||||||||

| Internalizing problems | −0.29 (−2.38, 1.80) | 0.788 | 0.04 (−2.05, 2.13) | 0.971 | −2.68 (−4.61, −0.75) | 0.007 | −2.50 (−4.43, −0.56) | 0.012 | −1.15 (−3.26, 0.96) | 0.285 | −1.07 (−3.19, 1.04) | 0.320 |

| Externalizing problems | −1.47 (−3.27, 0.33) | 0.110 | −1.02 (−2.79, 0.76) | 0.262 | −3.28 (−4.94, −1.61) | <0.001 | −2.75 (−4.40, −1.10) | 0.001 | −2.28 (−4.09, −0.46) | 0.014 | −1.88 (−3.68, −0.08) | 0.041 |

| Total problems | −1.16 (−3.20, 0.89) | 0.268 | −0.72 (−2.74, 1.31) | 0.488 | −3.32 (−5.21, −1.44) | 0.001 | −2.96 (−4.84, −1.07) | 0.002 | −2.01 (−4.08, 0.05) | 0.056 | −1.78 (−3.84, 0.28) | 0.090 |

| DSM-oriented problem | ||||||||||||

| Affective problems | −0.03 (−1.28, 1.21) | 0.957 | 0.06 (−1.18, 1.30) | 0.926 | −0.96 (−2.11, 0.18) | 0.100 | −0.97 (−2.12, 0.19) | 0.102 | −0.20 (−1.46, 1.05) | 0.751 | −0.25 (−1.51, 1.02) | 0.701 |

| Anxiety problems | −0.04 (−1.22, 1.13) | 0.816 | −0.04 (−1.22, 1.13) | 0.941 | −1.19 (−2.29, −0.10) | 0.039 | −1.19 (−2.29, −0.10) | 0.032 | −0.36 (−1.56, 0.83) | 0.631 | −0.36 (−1.56, 0.83) | 0.551 |

| Pervasive developmental problems | −0.38 (−1.70, 0.93) | 0.409 | −0.55 (−1.87, 0.76) | 0.569 | −1.24 (−2.46, −0.02) | 0.030 | −1.34 (−2.56, −0.13) | 0.047 | −0.49 (−1.83, 0.84) | 0.381 | −0.59 (−1.92, 0.73) | 0.469 |

| Attention deficit/hyperactivity problems | −0.82 (−1.78, 0.14) | 0.093 | −0.66 (−1.61, 0.29) | 0.175 | −1.55 (−2.43, −0.66) | 0.001 | −1.29 (−2.17, −0.41) | 0.004 | −1.05 (−2.02, −0.09) | 0.033 | −0.88 (−1.85, 0.08) | 0.074 |

| Oppositional defiant problems | −0.01 (−0.79, 0.76) | 0.97 | 0.07 (−0.71, 0.84) | 0.863 | −1.05 (−1.76, −0.33) | 0.004 | −0.93 (−1.65, −0.21) | 0.011 | −0.49 (−1.27, 0.29) | 0.222 | −0.39 (−1.18, 0.40) | 0.333 |

Notes: * Adjusted for maternal age, gestational week, education, occupation, BMI in early pregnancy, anemia in mid-pregnancy, supplementation during pregnancy, delivery mode, children’s sex, age, birthweight, main caregiver, and kindergarten attendance.

Figure 2.

Risks of child behavioral and emotional problems based on duration of breastfeeding, aOR (95% CI). Notes: Adjusted for maternal age, gestational week, education, occupation, BMI in early pregnancy, anemia in mid-pregnancy, supplementation during pregnancy, delivery mode, children’s sex, age, birthweight, main caregiver, and kindergarten attendance.

3.4. Subgroup Analysis Based on Children’s Sex

When we performed a subgroup analysis stratified by children’s sex, the significant associations of feeding patterns and breastfeeding duration with behavioral and emotional scales remained in boys but not in girls. In boys, compared with non-EBF children, those who underwent EBF had lower T scores for almost all behavioral and emotional scales except for sleep problems, stress problems, and DSM-V-oriented pervasive developmental problems (Table A3), and they had significantly lower risks of clinically internalizing problems, externalizing problems, total problems, as well as DSM-V-oriented attention deficit/hyperactivity problems (Table A4). As for the duration of breastfeeding, boys who were breastfed for 13–18 mo had lower T scores for internalizing problems, externalizing problems, total problems, emotionally reactive behavior, anxiety/depression, withdrawn behavior, attention problems, aggressive behavior, as well as DSM-V-oriented pervasive developmental problems, attention deficit/hyperactivity problems, and oppositional defiant problems (Table A5); they also had lower risks of clinically externalizing problems (Table A6).

4. Discussion

In this prospective cohort study among 2489 children from China, we found that breastfeeding practices including EBF for the first 6 mo of life and a prolonged duration of breastfeeding were significantly associated with better behavioral and emotional performance in children at ages in the range of 1.5–5.0 y. We also found that these beneficial associations were more likely exhibited in boys rather than in girls.

In our population, children who underwent EBF for the first 6 mo of life versus non-EBF children had lower T scores for behavioral and emotional problems and lower risks of the corresponding clinical problems. These findings were supported by a previous American study which examined the combined effects of EBF and breastfeeding duration on psychosocial development using the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire, a briefer tool in assessing behavioral performance. This study showed that ≥3 mo of EBF combined with ≥6 mo of breastfeeding versus non-breastfeeding was associated with better emotional and conduct performance in children at 6 y old [16]. Another cohort study in Chinese children aged 5 y also found that EBF children had a lower score of emotional problems assessed by CBCL compared to non-EBF children [17]. It is worth noting that the differences in symptoms or composite scores might not be clinically meaningful, but they are relevant on a population level [32].

Our study showed that a longer duration of breastfeeding was associated with better childhood behavioral and emotional development outcomes, whether measured continuously or categorically. These results were consistent with findings from most previous studies that examined the effect of breastfeeding duration within 12 mo, which reported that a longer duration of breastfeeding could improve behavioral and emotional performance in children [17,19,20,21,24,25,33]. When associations were observed, a duration of 4–6 mo appeared to be most common, and two studies extended the durations to 9 and 10 months. Our study extended the duration of breastfeeding to beyond 18 mo and found that the risks of total problems were significantly reduced in children who were breastfed for 13–18 mo versus those who were breastfed for ≤6 mo. Our study also extended previous work on the non-linear relationships between the duration of breastfeeding and the T scores of child behavioral and emotional problems. Inflection points were observed around 6 mo and 18 mo, and the T scores significantly decreased during the 6–18 mo period for both behavioral and emotional problems. These results support the WHO recommendations for breastfeeding children up to 2 y of age or beyond.

Several potential mechanisms may explain the links between breastfeeding practice and child behavioral and emotional development. First, breast milk contains large amounts of essential long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LCPUFAs), such as docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), which are essential for central nervous system development and may improve cognitive scores [34]. Second, the milk fat globule membrane (MFGM), a heterogeneous mixture of proteins, phospholipids, sphingolipids, gangliosides, choline, and sialic acid, improves neurodevelopment in cognitive, mental, and motor outcomes [35]. Third, non-nutrient bioactive factors in breast milk, such as human milk oligosaccharides (HMOs), lactoferrin, and microbes, were proven to have effects in early brain development [36,37]. These links could also be explained by mother–infant interaction during breastfeeding, which has been shown to benefit children’s behavioral outcomes through active talking, eye contact, and skin-to-skin touch [17]. As suggested by the differential susceptibility hypothesis, boys might be more sensitive to the aforementioned nutrient or non-nutrient exposure in early life, and more pronounced benefits of breastfeeding regarding behavioral and emotional development were exhibited [38], as shown in our subgroup analysis and the results from African children [39].

Our study also has some limitations. First, information on potential confounders, such as complementary feeding and formula types, was not collected in this study. Second, although the mothers generally had good mental health at recruitment, we did not collect data on maternal mental health, like postpartum anxiety, which might affect both feeding practices and children’s behavioral and emotional outcomes. Third, this study was conducted among a rural population, which limits the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, given the cohort study design, our findings might be influenced by residual confounding from unmeasured factors. Future studies considering mother–infant interaction are warranted to better understand the relationship between feeding practice and childhood neurobehavioral development.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, we found that EBF for the first 6 mo of life and a prolonged duration of breastfeeding, exclusively or partially, to 13–18 mo benefits childhood behavioral and emotional performance. Our findings support the WHO recommendation on breastfeeding up to 2 y and highlight the necessity of strengthening breastfeeding in China, where less than 40% of infants are exclusively breastfed for the first 6 mo of life [40]. Further studies across regions and among different populations with a stricter control of bias are warranted to confirm these associations and explore the underlying mechanisms.

Acknowledgments

We thank all physicians and other staff members who have contributed to this study across five counties (Fengrun, Mancheng, Laoting, Xianghe, and Yuanshi in Hebei Province, China). We are also indebted to all of the mother–child dyads who participated in this study for their cooperation.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Characteristics of excluded and included populations.

| Characteristics | Overall | Included | Excluded |

|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 17,613) | (N = 2489) | (N = 15,124) | |

| Maternal | |||

| Age, y, median (IQR) | 22.9 (3.20) | 22.7 (3.00) | 23.0 (3.20) |

| Gestational week, wk, mean (SD) | 39.6 (1.67) | 39.7 (1.57) | 39.6 (1.68) |

| Education, no. (%) | |||

| ≥High school | 3204 (18.2) | 397 (16.0) | 2807 (18.6) |

| Middle school | 14,130 (80.2) | 2066 (83.0) | 12,064 (79.8) |

| ≤Primary school | 279 (11.6) | 26 (1.0) | 253 (1.7) |

| Occupation, no. (%) | |||

| Farmer | 16,018 (90.9) | 2327 (93.5) | 13,691 (90.5) |

| Others | 1595 (9.1) | 162 (6.5) | 1433 (9.5) |

| BMI in early pregnancy, kg/m2, no. (%) | |||

| <18.5 | 1568 (8.9) | 207 (8.3) | 1361 (9.0) |

| 18.5–22.9 | 11,115 (63.1) | 1562 (62.8) | 9553 (63.2) |

| 23.0–27.4 | 4187 (23.8) | 612 (24.6) | 3575 (23.6) |

| ≥27.5 | 743 (4.2) | 108 (4.3) | 635 (4.2) |

| Anemia in mid-pregnancy, no. (%) | |||

| Yes | 16,402 (93.2) | 2329 (93.6) | 14,073 (93.1) |

| No | 1097 (6.2) | 149 (6.0) | 948 (6.3) |

| Missing | 114 (0.6) | 11 (0.4) | 103 (0.7) |

| Supplementation during pregnancy, no. (%) | |||

| Folic acid | 5861 (33.3) | 812 (32.6) | 5049 (33.4) |

| Iron–folic acid | 5882 (33.4) | 855 (34.4) | 5027 (33.2) |

| Multiple micronutrients | 5870 (33.3) | 822 (33.0) | 5048 (33.4) |

| Delivery mode, no. (%) | |||

| Vaginal delivery | 8995 (51.1) | 1300 (52.2) | 7695 (50.9) |

| Cesarean delivery | 8545 (48.5) | 1188 (47.7) | 7357 (48.6) |

| Missing | 73 (0.4) | 1 (0.0) | 72 (0.5) |

| Offspring | |||

| Age, mo, median (IQR) | 38.0 (1.00) | 39.0 (1.00) | 38.0 (1.00) |

| Sex, no. (%) | |||

| Male | 9240 (52.5) | 1290 (51.8) | 7950 (52.6) |

| Female | 8365 (47.5) | 1199 (48.2) | 7166 (47.4) |

| Missing | 8 (0.0) | 0 (0) | 8 (0.1) |

| Birthweight, g, mean (SD) | 3300 (386) | 3290 (377) | 3300 (388) |

| Feeding pattern for the first 6 mo, no. (%) | |||

| Exclusive breastfeeding | 12,342 (70.1) | 2085 (83.8) | 10,257 (67.2) |

| Non-exclusive breastfeeding | 2781 (15.8) | 404 (16.2) | 2377 (15.6) |

| Missing | 2625 (14.9) | 0 (0) | 2625 (17.2) |

| Duration of breastfeeding, mo, mean (SD) | 15.3 (5.26) | 15.5 (5.09) | 15.3 (5.30) |

| Main caregivers, no. (%) | |||

| Parents | 11,489 (65.2) | 1975 (79.3) | 9514 (62.9) |

| Grandparents | 3595 (20.4) | 510 (20.5) | 3085 (20.4) |

| Missing | 2529 (14.4) | 4 (0.2) | 2525 (16.7) |

| Kindergarten attendance, no. (%) | |||

| Yes | 8902 (50.5) | 1835 (73.7) | 7067 (46.7) |

| No | 6207 (35.2) | 650 (26.1) | 5557 (36.7) |

| Missing | 2504 (14.2) | 4 (0.2) | 2500 (16.5) |

Figure A1.

Restricted cubic spline curves depicting a non-linear relationship between the duration of breastfeeding and T scores of internalizing problems (A), externalizing problems (B), and total problems (C). Notes: Adjusted for maternal age, gestational week, education, occupation, BMI in early pregnancy, anemia in mid-pregnancy, supplementation during pregnancy, delivery mode, children’s sex, age, birthweight, main caregiver, and kindergarten attendance. The black solid line represents the fitted curve, and the gray area denotes the 95% confidence interval of the fitted values. The red dashed line indicates the location of the inflection point.

Table A2.

Segmented linear regression for association between duration of breastfeeding and T scores for internalizing problems, externalizing problems, and total problems.

| Items | ≤6 mo | 7–18 mo | >18 mo | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| βadj (95% CI) | p | βadj (95% CI) | p | βadj (95% CI) | p | |

| Syndrome | ||||||

| Emotionally reactive | 0.05 (−0.38, 0.49) | 0.813 | −0.14 (−0.23, −0.05) | 0.003 | 0.01 (−0.19, 0.21) | 0.927 |

| Anxious/depressed | 0.24 (−0.19, 0.66) | 0.274 | −0.16 (−0.25, −0.08) | <0.001 | 0.04 (−0.14, 0.21) | 0.664 |

| Somatic complaints | −0.08 (−0.56, 0.40) | 0.750 | −0.14 (−0.24, −0.04) | 0.005 | 0.14 (−0.05, 0.33) | 0.153 |

| Withdrawn behavior | 0.20 (−0.25, 0.64) | 0.390 | −0.19 (−0.30, −0.09) | <0.001 | 0.18 (−0.03, 0.39) | 0.099 |

| Sleep problems | 0.01 (−0.31, 0.33) | 0.957 | −0.04 (−0.10, 0.02) | 0.228 | −0.02 (−0.14, 0.10) | 0.718 |

| Attention problems | 0.02 (−0.36, 0.39) | 0.929 | −0.06 (−0.14, 0.02) | 0.122 | 0.04 (−0.13, 0.20) | 0.674 |

| Aggressive behavior | −0.15 (−0.56, 0.27) | 0.494 | −0.11 (−0.19, −0.04) | 0.002 | 0.12 (−0.03, 0.28) | 0.125 |

| Stress problems | −0.07 (−0.47, 0.33) | 0.728 | −0.13 (−0.22, −0.05) | 0.003 | 0.06 (−0.12, 0.24) | 0.532 |

| Composite problem | ||||||

| Internalizing problems | 0.41 (−0.40, 1.22) | 0.321 | −0.39 (−0.57, −0.21) | <0.001 | 0.19 (−0.17, 0.55) | 0.303 |

| Externalizing problems | 0.02 (−0.69, 0.72) | 0.960 | −0.27 (−0.42, −0.12) | <0.001 | 0.15 (−0.16, 0.47) | 0.333 |

| Total problems | 0.21 (−0.60, 1.03) | 0.610 | −0.33 (−0.50, −0.15) | <0.001 | 0.19 (−0.17, 0.54) | 0.302 |

| DSM-oriented problem | ||||||

| Affective problems | 0.23 (−0.28, 0.74) | 0.375 | −0.14 (−0.25, −0.04) | 0.007 | 0.14 (−0.08, 0.37) | 0.216 |

| Anxiety problems | −0.10 (−0.61, 0.41) | 0.713 | −0.17 (−0.27, −0.07) | 0.001 | 0.02 (−0.19, 0.23) | 0.866 |

| Pervasive developmental problems | 0.02 (−0.50, 0.54) | 0.948 | −0.13 (−0.24, −0.02) | 0.023 | 0.23 (0.01, 0.46) | 0.045 |

| Attention deficit/hyperactivity problems | −0.22 (−0.62, 0.18) | 0.279 | −0.03 (−0.11, 0.05) | 0.504 | −0.05 (−0.22, 0.11) | 0.529 |

| Oppositional defiant problems | −0.04 (−0.36, 0.28) | 0.824 | −0.15 (−0.21, −0.08) | <0.001 | 0.11 (−0.04, 0.27) | 0.146 |

Notes: Negative values indicate decrease in T score of behavioral and emotional problems, which means better behavioral and emotional development; positive values indicate increase in T score of behavioral and emotional problems, which means worse behavioral and emotional development. All models were adjusted for maternal age, gestational week, education, occupation, BMI in early pregnancy, anemia in mid-pregnancy, supplementation during pregnancy, delivery mode, children’s sex, age, birthweight, main caregiver, and kindergarten attendance.

Table A3.

Mean differences in T scores for childhood behavioral and emotional problems based on feeding pattern (EBF vs. non-EBF) for first 6 mo of life stratified by children’s sex.

| Items | Boys (n = 1290) | Girls (n = 1199) | p for Interaction | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aMD (95% CI) | p | aMD (95% CI) | p | ||

| Syndrome | |||||

| Emotionally reactive | −1.01 (−1.81, −0.20) | 0.014 | 0.19 (−0.79, 1.16) | 0.707 | 0.093 |

| Anxious/depressed | −1.04 (−1.82, −0.26) | 0.009 | 0.25 (−0.68, 1.17) | 0.602 | 0.029 |

| Somatic complaints | −1.03 (−1.95, −0.11) | 0.028 | −1.53 (−2.52, −0.53) | 0.003 | 0.479 |

| Withdrawn behavior | −1.14 (−2.08, −0.20) | 0.018 | 0.70 (−0.42, 1.83) | 0.220 | 0.009 |

| Sleep problems | −0.25 (−0.78, 0.29) | 0.365 | 0.05 (−0.64, 0.74) | 0.884 | 0.458 |

| Attention problems | −0.85 (−1.56, −0.14) | 0.019 | 0.51 (−0.27, 1.28) | 0.198 | 0.011 |

| Aggressive behavior | −1.20 (−1.92, −0.47) | 0.001 | 0.24 (−0.48, 0.95) | 0.518 | 0.009 |

| Stress problems | −0.71 (−1.51, 0.09) | 0.083 | −0.15 (−1.08, 0.77) | 0.749 | 0.423 |

| Composite problem | |||||

| Internalizing problems | −2.12 (−3.75, −0.50) | 0.011 | −0.16 (−2.00, 1.67) | 0.862 | 0.115 |

| Externalizing problems | −1.87 (−3.29, −0.46) | 0.010 | 0.41 (−1.11, 1.93) | 0.599 | 0.048 |

| Total problems | −2.24 (−3.83, −0.65) | 0.006 | 0.11 (−1.66, 1.88) | 0.902 | 0.056 |

| DSM-oriented problem | |||||

| Affective problems | −0.97 (−1.91, −0.03) | 0.043 | 0.08 (−1.05, 1.20) | 0.894 | 0.080 |

| Anxiety problems | −1.24 (−2.13, −0.34) | 0.007 | −0.20 (−1.26, 0.86) | 0.711 | 0.149 |

| Pervasive developmental problems | −0.99 (−2.00, 0.01) | 0.053 | 0.40 (−0.78, 1.58) | 0.509 | 0.071 |

| Attention deficit/hyperactivity problems | −0.92 (−1.69, −0.15) | 0.019 | 0.15 (−0.64, 0.95) | 0.706 | 0.048 |

| Oppositional defiant problems | −0.72 (−1.36, −0.07) | 0.029 | 0.15 (−0.48, 0.79) | 0.636 | 0.071 |

Notes: Adjusted for maternal age, gestational week, education, occupation, BMI in early pregnancy, anemia in mid-pregnancy, supplementation during pregnancy, delivery mode, children’s sex, age, birthweight, main caregiver, and kindergarten attendance. p for interaction was p-value of interaction term for sex and feeding pattern for first 6 mo.

Table A4.

Risks of child behavioral and emotional problems based on feeding pattern (EBF vs. non-EBF) for first 6 mo stratified by children’s sex.

| Items | Boys (n = 1290) | Girls (n = 1199) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| aOR (95% CI) | p | aOR (95% CI) | p | |

| Syndrome | ||||

| Emotionally reactive | 0.67 (0.17, 2.58) | 0.558 | 1.26 (0.27, 5.86) | 0.772 |

| Anxious/depressed | 1.19 (0.33, 4.35) | 0.788 | 1.09 (0.31, 3.92) | 0.890 |

| Somatic complaints | 0.75 (0.37, 1.55) | 0.442 | 0.52 (0.22, 1.19) | 0.122 |

| Withdrawn behavior | 0.81 (0.42, 1.59) | 0.544 | 1.58 (0.70, 3.60) | 0.271 |

| Sleep problems | / | 0.997 | 0.72 (0.14, 3.66) | 0.695 |

| Attention problems | 0.53 (0.19, 1.44) | 0.210 | 2.02 (0.45, 9.08) | 0.361 |

| Aggressive behavior | 1.61 (0.35, 7.45) | 0.542 | 2.04 (0.17, 24.52) | 0.572 |

| Stress problems | 1.40 (0.52, 3.75) | 0.503 | 0.95 (0.38, 2.38) | 0.918 |

| Composite problem | ||||

| Internalizing problems | 0.62 (0.39, 0.97) | 0.037 | 0.98 (0.57, 1.70) | 0.956 |

| Externalizing problems | 0.40 (0.23, 0.71) | 0.002 | 1.07 (0.40, 2.87) | 0.895 |

| Total problems | 0.54 (0.33, 0.86) | 0.011 | 1.02 (0.53, 1.95) | 0.958 |

| DSM-oriented problem | ||||

| Affective problems | 0.67 (0.38, 1.20) | 0.180 | 0.98 (0.50, 1.94) | 0.951 |

| Anxiety problems | 0.60 (0.30, 1.19) | 0.145 | 0.82 (0.39, 1.75) | 0.610 |

| Pervasive developmental problems | 0.79 (0.44, 1.43) | 0.432 | 1.01 (0.51, 1.98) | 0.980 |

| Attention deficit/hyperactivity problems | 0.34 (0.14, 0.80) | 0.014 | 0.46 (0.14, 1.46) | 0.187 |

| Oppositional defiant problems | 1.44 (0.47, 4.42) | 0.525 | 2.50 (0.31, 19.90) | 0.388 |

Notes: Adjusted for maternal age, gestational week, education, occupation, BMI in early pregnancy, anemia in mid-pregnancy, supplementation during pregnancy, delivery mode, children’s sex, age, birthweight, main caregiver, and kindergarten attendance.

Table A5.

Mean differences in T scores for childhood behavioral and emotional problems based on duration of breastfeeding, stratified by children’s sex, aMD (95% CI).

| Items | Boys (n = 1290) | Girls (n = 1199) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7–12 mo | p | 13–18 mo | p | >18 mo | p | 7–12 mo | p | 13–18 mo | p | >18 mo | p | |

| Syndrome | ||||||||||||

| Emotionally reactive | −0.58 (−1.97, 0.80) | 0.411 | −1.58 (−2.85, −0.31) | 0.015 | −0.88 (−2.27, 0.52) | 0.218 | −0.01 (−1.68, 1.66) | 0.990 | −0.70 (−2.27, 0.88) | 0.387 | −0.57 (−2.27, 1.14) | 0.515 |

| Anxious/depressed | −0.14 (−1.48, 1.20) | 0.838 | −1.75 (−2.97, −0.52) | 0.005 | −1.07 (−2.42, 0.27) | 0.119 | 0.93 (−0.65, 2.51) | 0.250 | 0.16 (−1.33, 1.65) | 0.832 | 0.24 (−1.37, 1.85) | 0.769 |

| Somatic complaints | 0.47 (−1.11, 2.06) | 0.558 | −1.38 (−2.83, 0.07) | 0.063 | −0.80 (−2.39, 0.80) | 0.326 | −0.12 (−1.83, 1.60) | 0.895 | −0.66 (−2.28, 0.96) | 0.424 | −0.82 (−2.57, 0.93) | 0.358 |

| Withdrawn behavior | −0.43 (−2.06, 1.20) | 0.607 | −1.67 (−3.16, −0.18) | 0.028 | −0.59 (−2.23, 1.05) | 0.484 | 1.09 (−0.84, 3.02) | 0.269 | 0.25 (−1.57, 2.06) | 0.791 | 0.22 (−1.75, 2.18) | 0.830 |

| Sleep problems | 0.23 (−0.69, 1.16) | 0.621 | −0.12 (−0.97, 0.73) | 0.785 | −0.04 (−0.97, 0.90) | 0.939 | 0.16 (−1.02, 1.34) | 0.789 | −0.08 (−1.19, 1.03) | 0.893 | 0.09 (−1.12, 1.29) | 0.889 |

| Attention problems | −0.48 (−1.71, 0.74) | 0.440 | −1.49 (−2.61, −0.36) | 0.010 | −1.13 (−2.36, 0.11) | 0.074 | −0.17 (−1.50, 1.16) | 0.801 | −0.35 (−1.61, 0.90) | 0.580 | −0.31 (−1.67, 1.05) | 0.655 |

| Aggressive behavior | −0.54 (−1.79, 0.71) | 0.397 | −1.89 (−3.03, −0.74) | 0.001 | −1.15 (−2.41, 0.11) | 0.074 | −0.51 (−1.73, 0.72) | 0.416 | −0.82 (−1.97, 0.34) | 0.165 | −0.89 (−2.14, 0.36) | 0.161 |

| Stress problems | 0.40 (−0.98, 1.78) | 0.573 | −1.02 (−2.28, 0.25) | 0.115 | −0.40 (−1.79, 0.99) | 0.574 | 0.37 (−1.22, 1.95) | 0.649 | −0.06 (−1.56, 1.43) | 0.934 | −0.46 (−2.07, 1.16) | 0.581 |

| Composite problem | ||||||||||||

| Internalizing problems | −0.43 (−3.23, 2.37) | 0.766 | −3.48 (−6.05, −0.92) | 0.008 | −1.31 (−4.13, 1.51) | 0.361 | 0.76 (−2.38, 3.91) | 0.636 | −1.04 (−4.01, 1.92) | 0.490 | −0.54 (−3.75, 2.67) | 0.742 |

| Externalizing problems | −0.76 (−3.20, 1.68) | 0.544 | −3.26 (−5.50, −1.03) | 0.004 | −1.63 (−4.09, 0.83) | 0.194 | −1.29 (−3.89, 1.32) | 0.334 | −2.09 (−4.54, 0.37) | 0.097 | −2.16 (−4.82, 0.50) | 0.112 |

| Total problems | −0.65 (−3.39, 2.09) | 0.642 | −3.57 (−6.08, −1.06) | 0.005 | −1.76 (−4.52, 1.00) | 0.212 | −0.67 (−3.70, 2.36) | 0.666 | −2.04 (−4.89, 0.82) | 0.162 | −1.67 (−4.76, 1.42) | 0.289 |

| DSM-oriented problem | ||||||||||||

| Affective problems | 0.07 (−1.56, 1.69) | 0.937 | −1.41 (−2.90, 0.08) | 0.063 | −0.26 (−1.89, 1.38) | 0.760 | 0.15 (−1.78, 2.08) | 0.882 | −0.33 (−2.15, 1.49) | 0.722 | −0.07 (−2.04, 1.90) | 0.944 |

| Anxiety problems | −0.86 (−2.41, 0.68) | 0.272 | −1.99 (−3.40, −0.58) | 0.006 | −1.12 (−2.67, 0.44) | 0.159 | 0.98 (−0.84, 2.80) | 0.291 | −0.08 (−1.79, 1.64) | 0.930 | 0.65 (−1.20, 2.51) | 0.490 |

| Pervasive developmental problems | −1.24 (−2.98, 0.51) | 0.180 | −2.02 (−3.61, −0.44) | 0.015 | −0.85 (−2.59, 0.90) | 0.417 | 0.31 (−1.69, 2.32) | 0.627 | −0.47 (−2.34, 1.41) | 0.779 | −0.19 (−2.24, 1.85) | 0.892 |

| Attention deficit/hyperactivity problems | −0.35 (−1.69, 0.98) | 0.604 | −1.44 (−2.67, −0.22) | 0.021 | −0.96 (−2.31, 0.38) | 0.160 | −1.03 (−2.39, 0.34) | 0.140 | −1.13 (−2.42, 0.16) | 0.086 | −0.82 (−2.22, 0.57) | 0.246 |

| Oppositional defiant problems | −0.11 (−1.22, 0.99) | 0.840 | −1.33 (−2.35, −0.32) | 0.010 | −0.52 (−1.64, 0.59) | 0.357 | 0.27 (−0.82, 1.36) | 0.626 | −0.47 (−1.49, 0.55) | 0.369 | −0.22 (−1.33, 0.89) | 0.700 |

Notes: Adjusted for maternal age, gestational week, education, occupation, BMI in early pregnancy, anemia in mid-pregnancy, supplementation during pregnancy, delivery mode, children’s sex, age, birthweight, main caregiver, and kindergarten attendance.

Table A6.

Risks of childhood behavioral and emotional problems based on duration of breastfeeding, stratified by children’s sex, aOR (95% CI).

| Items | Boys (n = 1290) | Girls (n = 1199) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7–12 mo | p | 13–18 mo | p | >18 mo | p | 7–12 mo | p | 13–18 mo | p | >18 mo | p | |

| Syndrome | ||||||||||||

| Emotionally reactive | 1.01 (0.98, 1.04) | 0.439 | 0.99 (0.97, 1.01) | 0.419 | 1.01 (0.98, 1.03) | 0.530 | 1.00 (0.97, 1.04) | 0.940 | 1.00 (0.97, 1.03) | 0.998 | 0.99 (0.96, 1.03) | 0.693 |

| Anxious/depressed | 1.01 (0.98, 1.04) | 0.421 | 0.98 (0.95, 1.01) | 0.209 | 0.99 (0.96, 1.02) | 0.401 | 1.01 (0.97, 1.05) | 0.568 | 1.00 (0.96, 1.04) | 0.996 | 1.01 (0.97, 1.05) | 0.751 |

| Somatic complaints | 1.01 (0.96, 1.06) | 0.818 | 0.98 (0.94, 1.02) | 0.322 | 0.97 (0.93, 1.02) | 0.247 | 0.99 (0.94, 1.04) | 0.600 | 0.99 (0.94, 1.03) | 0.537 | 0.97 (0.93, 1.02) | 0.255 |

| Withdrawn behavior | 1.00 (0.95, 1.05) | 0.890 | 0.98 (0.94, 1.03) | 0.424 | 0.96 (0.91, 1.01) | 0.136 | 1.01 (0.95, 1.08) | 0.691 | 0.98 (0.93, 1.05) | 0.621 | 0.99 (0.92, 1.05) | 0.677 |

| Sleep problems | 1.01 (0.99, 1.02) | 0.264 | 1.01 (0.99, 1.02) | 0.448 | 1.00 (0.99, 1.02) | 0.676 | 0.98 (0.95, 1.01) | 0.158 | 0.97 (0.95, 1.00) | 0.034 | 0.98 (0.95, 1.00) | 0.077 |

| Attention problems | 1.00 (0.96, 1.03) | 0.833 | 0.99 (0.96, 1.02) | 0.454 | 0.99 (0.96, 1.03) | 0.708 | 0.99 (0.95, 1.03) | 0.626 | 0.99 (0.96, 1.03) | 0.584 | 0.99 (0.96, 1.03) | 0.741 |

| Aggressive behavior | 1.02 (0.99, 1.05) | 0.207 | 0.99 (0.96, 1.01) | 0.391 | 1.01 (0.98, 1.04) | 0.405 | 0.99 (0.96, 1.01) | 0.281 | 0.99 (0.97, 1.02) | 0.569 | 0.99 (0.97, 1.02) | 0.476 |

| Stress problems | 1.03 (0.98, 1.07) | 0.233 | 0.99 (0.96, 1.03) | 0.724 | 1.00 (0.96, 1.04) | 0.992 | 0.98 (0.93, 1.03) | 0.476 | 0.97 (0.92, 1.02) | 0.202 | 0.96 (0.91, 1.01) | 0.137 |

| Composite problem | ||||||||||||

| Internalizing problems | 0.97 (0.90, 1.04) | 0.374 | 0.93 (0.87, 1.00) | 0.039 | 0.94 (0.88, 1.02) | 0.134 | 0.99 (0.91, 1.08) | 0.829 | 0.96 (0.89, 1.04) | 0.368 | 0.97 (0.89, 1.06) | 0.542 |

| Externalizing problems | 0.94 (0.89, 1.00) | 0.035 | 0.91 (0.87, 0.96) | <0.001 | 0.94 (0.89, 0.99) | 0.031 | 0.97 (0.93, 1.02) | 0.285 | 0.99 (0.94, 1.03) | 0.519 | 0.98 (0.93, 1.03) | 0.457 |

| Total problems | 1.00 (0.93, 1.07) | 0.937 | 0.94 (0.88, 1.00) | 0.038 | 0.96 (0.89, 1.03) | 0.209 | 0.99 (0.92, 1.06) | 0.786 | 0.96 (0.90, 1.03) | 0.230 | 0.98 (0.91, 1.06) | 0.678 |

| DSM-oriented problem | ||||||||||||

| Affective problems | 1.02 (0.96, 1.08) | 0.497 | 0.98 (0.93, 1.03) | 0.383 | 1.00 (0.94, 1.06) | 0.974 | 0.98 (0.92, 1.05) | 0.603 | 0.97 (0.91, 1.04) | 0.399 | 1.00 (0.93, 1.07) | 0.926 |

| Anxiety problems | 1.00 (0.95, 1.05) | 0.959 | 0.96 (0.92, 1.01) | 0.087 | 0.99 (0.94, 1.04) | 0.575 | 1.02 (0.96, 1.08) | 0.611 | 0.99 (0.94, 1.05) | 0.793 | 1.00 (0.94, 1.06) | 0.984 |

| Pervasive developmental problems | 0.98 (0.92, 1.04) | 0.433 | 0.96 (0.91, 1.01) | 0.148 | 0.98 (0.92, 1.04) | 0.499 | 0.96 (0.89, 1.03) | 0.214 | 0.94 (0.88, 1.00) | 0.070 | 0.94 (0.87, 1.00) | 0.067 |

| Attention deficit/hyperactivity problems | 1.02 (0.98, 1.05) | 0.389 | 1.00 (0.97, 1.04) | 0.799 | 1.00 (0.97, 1.04) | 0.830 | 0.96 (0.93, 0.99) | 0.007 | 0.95 (0.92, 0.97) | <0.001 | 0.94 (0.91, 0.97) | <0.001 |

| Oppositional defiant problems | 1.00 (0.97, 1.04) | 0.872 | 0.97 (0.94, 1.00) | 0.057 | 0.99 (0.95, 1.02) | 0.498 | 1.01 (0.98, 1.05) | 0.489 | 1.01 (0.98, 1.05) | 0.348 | 1.02 (0.99, 1.05) | 0.237 |

Notes: Adjusted for maternal age, gestational week, education, occupation, BMI in early pregnancy, anemia in mid-pregnancy, supplementation during pregnancy, delivery mode, children’s sex, age, birthweight, main caregiver, and kindergarten attendance.

Author Contributions

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows: Conceptualization, J.L. and Y.Z.; methodology, J.L. and Y.Z.; validation, Y.M. and H.Y.; formal analysis, Y.M.; investigation, Y.Z., H.L. and J.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.M.; writing—review and editing, J.L., Y.Z., Y.M., H.Y. and M.Z.; visualization, Y.M. and H.Y.; supervision, J.L. and H.L.; project administration, J.L.; funding acquisition, J.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Both the RCT and the follow-up study were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Peking University Institutional Review Board (approval code: IRB00001052-09075, approval date: 29 October 2009), and this study is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (identifiers: NCT00133744, first registered at 24 August 2005; NCT01404416, first registered at 28 July 2011).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data are presented in the manuscript; the code book and analytic code will not be made available because specific consent has not been obtained from the participants nor the Ethics Committee when receiving approval for this study at the time it was conducted.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

This study was funded by the National Basic Research Program of China (no. 2007CB5119001) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 81571517).

Footnotes

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

References

- 1.Belfer M.L. Child and adolescent mental disorders: The magnitude of the problem across the globe. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 2008;49:226–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01855.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Orri M., Galera C., Turecki G., Forte A., Renaud J., Boivin M., Tremblay R.E., Côté S.M., Geoffroy M.-C. Association of Childhood Irritability and Depressive/Anxious Mood Profiles With Adolescent Suicidal Ideation and Attempts. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75:465–473. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.0174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bevilacqua L., Hale D., Barker E.D., Viner R. Conduct Problems Trajectories and Psychosocial Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2018;27:1239–1260. doi: 10.1007/s00787-017-1053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rescorla L.A., Jordan P., Zhang S., Baelen-King G., Althoff R.R., Ivanova M.Y., International Aseba Consortium Latent Class Analysis of the CBCL Dysregulation Profile for 6- to 16-Year-Olds in 29 Societies. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2021;50:551–564. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2019.1697929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Egger H.L., Angold A. Common emotional and behavioral disorders in preschool children: Presentation, nosology, and epidemiology. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 2006;47:313–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cui Y., Li F., Leckman J.F., Guo L., Ke X., Liu J., Zheng Y., Li Y. The prevalence of behavioral and emotional problems among Chinese school children and adolescents aged 6-16: A national survey. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2021;30:233–241. doi: 10.1007/s00787-020-01507-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodríguez-Barranco M., Lacasaña M., Aguilar-Garduño C., Alguacil J., Gil F., González-Alzaga B., Rojas-García A. Association of arsenic, cadmium and manganese exposure with neurodevelopment and behavioural disorders in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2013;454–455:562–577. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.03.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hosokawa R., Katsura T. Effect of socioeconomic status on behavioral problems from preschool to early elementary school—A Japanese longitudinal study. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0197961. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0197961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cimino S., Cerniglia L., Ballarotto G., Marzilli E., Pascale E., D’Addario C., Adriani W., Maremmani A.G.I., Tambelli R. Children’s DAT1 Polymorphism Moderates the Relationship Between Parents’ Psychological Profiles, Children’s DAT Methylation, and Their Emotional/Behavioral Functioning in a Normative Sample. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2019;16:2567. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16142567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization. United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) Global Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koletzko B., Lien E., Agostoni C., Böhles H., Campoy C., Cetin I., Decsi T., Dudenhausen J.W., Dupont C., Forsyth S., et al. The roles of long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in pregnancy, lactation and infancy: Review of current knowledge and consensus recommendations. J. Perinat. Med. 2008;36:5–14. doi: 10.1515/JPM.2008.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fergusson D.M., Woodward L.J. Breast feeding and later psychosocial adjustment. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 1999;13:144–157. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3016.1999.00167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meek J.Y., Noble L. Section on Breastfeeding Policy Statement: Breastfeeding and the Use of Human Milk. Pediatrics. 2022;150:e2022057988. doi: 10.1542/peds.2022-057988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ip S., Chung M., Raman G., Chew P., Magula N., DeVine D., Trikalinos T., Lau J. Breastfeeding and Maternal and Infant Health Outcomes in Developed Countries. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); Rockville, MD, USA: 2007. pp. 1–186. Evidence Reports/Technology Assessments. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horta B.L., Loret de Mola C., Victora C.G. Breastfeeding and intelligence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Paediatr. 2015;104:14–19. doi: 10.1111/apa.13139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lind J.N., Li R., Perrine C.G., Schieve L.A. Breastfeeding and later psychosocial development of children at 6 years of age. Pediatrics. 2014;134((Suppl. S1)):S36–S41. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-0646G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu J., Leung P., Yang A. Breastfeeding and active bonding protects against children’s internalizing behavior problems. Nutrients. 2013;6:76–89. doi: 10.3390/nu6010076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Julvez J., Ribas-Fitó N., Forns M., Garcia-Esteban R., Torrent M., Sunyer J. Attention behaviour and hyperactivity at age 4 and duration of breast-feeding. Acta Paediatr. 2007;96:842–847. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heikkilä K., Sacker A., Kelly Y., Renfrew M.J., Quigley M.A. Breast feeding and child behaviour in the Millennium Cohort Study. Arch. Dis. Child. 2011;96:635–642. doi: 10.1136/adc.2010.201970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Speyer L.G., Hall H.A., Ushakova A., Murray A.L., Luciano M., Auyeung B. Longitudinal effects of breast feeding on parent-reported child behaviour. Arch. Dis. Child. 2021;106:355–360. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2020-319038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oddy W.H., Kendall G.E., Li J., Jacoby P., Robinson M., de Klerk N.H., Silburn S.R., Zubrick S.R., Landau L.I., Stanley F.J. The long-term effects of breastfeeding on child and adolescent mental health: A pregnancy cohort study followed for 14 years. J. Pediatr. 2010;156:568–574. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Girard L.-C., Farkas C. Breastfeeding and behavioural problems: Propensity score matching with a national cohort of infants in Chile. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e025058. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Belfort M.B., Rifas-Shiman S.L., Kleinman K.P., Bellinger D.C., Harris M.H., Taveras E.M., Gillman M.W., Oken E. Infant Breastfeeding Duration and Mid-Childhood Executive Function, Behavior, and Social-Emotional Development. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2016;37:43–52. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang T., Yue Y., Wang H., Zheng J., Chen Z., Chen T., Zhang M., Wang S. Infant Breastfeeding and Behavioral Disorders in School-Age Children. Breastfeed. Med. Off. J. Acad. Breastfeed. Med. 2019;14:115–120. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2018.0151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu F., Ma L.-J., Yi M.-J. Association of breastfeeding with behavioral problems and temperament development in children aged 4–5 years. Zhongguo Dang Dai Er Ke Za Zhi/Chin. J. Contemp. Pediatr. 2006;8:334–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu J., Mei Z., Ye R., Serdula M.K., Ren A., Cogswell M.E. Micronutrient supplementation and pregnancy outcomes: Double-blind randomized controlled trial in China. JAMA Intern. Med. 2013;173:276–282. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.1632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.World Health Organization . Indicators for Assessing Breast-Feeding Practices. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rescorla L.A., Achenbach T. Manual for the ASEBA Preschool Forms & Profiles. Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families, University of Vermont; Burlington, NJ, USA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 29.World Health Organization . Haemoglobin Concentrations for the Diagnosis of Anaemia and Assessment of Severity. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 30.WHO Expert Consultation Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet. 2004;363:157–163. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15268-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hofheimer J.A., McGrath M., Musci R., Wu G., Polk S., Blackwell C.K., Stroustrup A., Annett R.D., Aschner J., Carter B.S., et al. Assessment of Psychosocial and Neonatal Risk Factors for Trajectories of Behavioral Dysregulation Among Young Children from 18 to 72 Months of Age. JAMA Netw. Open. 2023;6:e2310059. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.10059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bellinger D.C. What is an adverse effect? A possible resolution of clinical and epidemiological perspectives on neurobehavioral toxicity. Environ. Res. 2004;95:394–405. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2003.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Girard L.-C., Doyle O., Tremblay R.E. Breastfeeding, Cognitive and Noncognitive Development in Early Childhood: A Population Study. Pediatrics. 2017;139:e20161848. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Makrides M., Uauy R. LCPUFAs as conditionally essential nutrients for very low birth weight and low birth weight infants: Metabolic, functional, and clinical outcomes-how much is enough? Clin. Perinatol. 2014;41:451–461. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2014.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brink L.R., Lönnerdal B. Milk fat globule membrane: The role of its various components in infant health and development. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2020;85:108465. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2020.108465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lis-Kuberka J., Orczyk-Pawiłowicz M. Sialylated Oligosaccharides and Glycoconjugates of Human Milk. The Impact on Infant and Newborn Protection, Development and Well-Being. Nutrients. 2019;11:306. doi: 10.3390/nu11020306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fleming S.A., Mudd A.T., Hauser J., Yan J., Metairon S., Steiner P., Donovan S.M., Dilger R.N. Human and Bovine Milk Oligosaccharides Elicit Improved Recognition Memory Concurrent with Alterations in Regional Brain Volumes and Hippocampal mRNA Expression. Front. Neurosci. 2020;14:770. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2020.00770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Belsky J., Bakermans-Kranenburg M.J., Van IJzendoorn M.H. For better and for worse differential susceptibility to environmental influences. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2007;16:300–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00525.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rochat T.J., Houle B., Stein A., Coovadia H., Coutsoudis A., Desmond C., Newell M.-L., Bland R.M. Exclusive Breastfeeding and Cognition, Executive Function, and Behavioural Disorders in Primary School-Aged Children in Rural South Africa: A Cohort Analysis. PLoS Med. 2016;13:e1002044. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li Q., Tian J., Xu F., Binns C. Breastfeeding in China: A Review of Changes in the Past Decade. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17:8234. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17218234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data are presented in the manuscript; the code book and analytic code will not be made available because specific consent has not been obtained from the participants nor the Ethics Committee when receiving approval for this study at the time it was conducted.