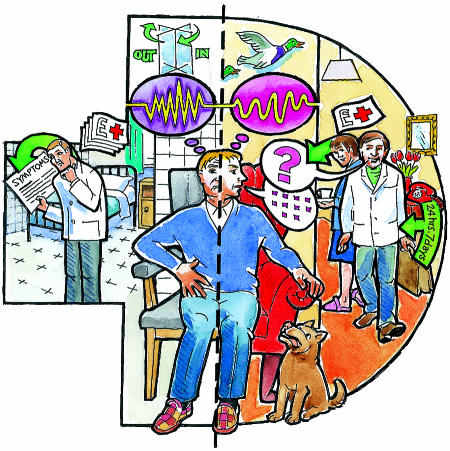

Why is home treatment for acute psychiatric illness generally ignored as an alternative to conventional admission to hospital in the United Kingdom? Despite evidence showing that home treatment is feasible, effective, and generally preferred by patients and relatives, its widespread implementation is still awaited. Furthermore, no study has shown that hospital treatment is better than home treatment for any measure of improvement. In general, patients are denied the option of home treatment as a realistic, less restrictive alternative to formal admission under the Mental Health Act 1983, although the recent white paper Modernising Mental Health Services recommends that it should be provided.1

In any economic analysis, hospital admission remains the most expensive element of psychiatric care. Although the pressure on acute beds in inner city psychiatric hospitals in the United Kingdom is increasing—and it has reached breaking point in some areas2,3—it is claimed that managing these patients outside hospital would be out of the question.4 The pressure on hospital beds has been linked indirectly with the practice of discharging psychiatric patients too early and with well publicised reports of official inquiries into “psychiatric scandals.” In a recent article that was critical of the current state of British psychiatry, it was alleged that the Department of Health and health authorities had misconstrued research into home treatment and that this had resulted in a reduction in the provision of acute beds.4 We aim to examine the issues, real and imagined, that are behind the resistance to treatment at home.

Summary points

Home treatment is a safe and feasible alternative to hospital care for patients with acute psychiatric disorder, and one that they and their carers generally prefer

Hospital treatment has not been shown to have major advantages over home treatment and is more expensive

Home treatment has not been widely supported and adopted in the United Kingdom

This delayed implementation reflects criticism that is largely unfounded

Home treatment is valuable in its own right, but its ultimate usefulness is as part of an integrated comprehensive community strategy that includes assertive outreach services

SUE SHARPLES

What is home treatment?

By home treatment we mean a service for people with serious mental illness who are in crisis and are candidates for admission to hospital. A home treatment team does not stand alone. It is an integral part of the overall provision for psychiatric care and plugs a gap between community mental health teams and inpatient units. The features of an effective home treatment team are set out in the box.

Features of an effective home treatment team

Available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week

Capable of rapid response—usually within the hour in urban areas

Able to spend time flexibly with the patient and their social network, including several visits daily if required

Addresses the social issues surrounding the crisis right from the beginning

Medical staff accompany the team at assessment and are available round the clock

Is able to administer and supervise medication

Can provide practical, problem solving help

Is able to provide explanation, advice, and support for carers

Provides counselling

Acts as a gatekeeper to acute inpatient care

Remains involved throughout the crisis until its resolution

Ensures that patients are linked up to further, continuing care

The research evidence

Home treatment has been shown empirically to be safe, effective, and feasible for up 80% of patients presenting for admission to hospital.5–12 In these studies patients have been randomised to home or inpatient treatment at the time of admission. Five reviews have endorsed positively the overall findings.13–17

Advantages

Research points to the advantages of home treatment. These are set out below.

Reduced admissions and bed use

Studies show that home treatment can reduce admissions to hospital by a mean of 66%.5–11 The most pessimistic calculation, based on adequately randomised controlled studies only, yields a figure of 55%.14 Those who advocate this model have never claimed that inpatient beds are no longer necessary. The disadvantages of admission to hospital include: cost, emotional trauma,18 stigma (still attached by the public to patients who have been admitted to a psychiatric hospital), delay in recognising social problems, increased likelihood of readmission (at worst, leading to the “revolving door syndrome”), and “medicalisation.” With regard to this last point, the focus in hospital may be on symptoms and behavioural conformity. Patients in hospital quickly learn that staff are interested in symptoms and this can dominate the discourse and clinical decision making. However, even when a patient is admitted to hospital, the length of stay can be reduced appreciably by home treatment. This has been described as a reduction in the stay of up to 80%19or a home:hospital bed day ratio of 17:60.15

Patients' and relatives' preference

We know of no study in which most subjects have preferred hospital admission to a reasonable alternative. When asked by researchers why they did not like hospital, inpatients discussed issues such as deprivation of liberty, lack of autonomy, unsatisfactory surroundings, lack of status and recognition, an emphasis on behavioural conformity, and removal from their family.20

Equal clinical outcomes

Studies mainly involve patients with severe mental illness (functional psychosis accounts for 75% of cases on average). Most reports show that the clinical outcome is similar in patients treated at home or in hospital.

Burden on relatives

Carers are more willing to help the patient at home and avoid the disruption and trauma of admission when they know that immediate help is at hand. Carers witness at first hand the interaction of staff and patients and are better informed about the disorder and the management of eventualities, and of the rationale for different drug treatments. In hospital, carers may never see the medical or nursing staff working directly with the patient.

Better service retention

Higher patient satisfaction should not be dismissed as a “soft” finding. This preference is reflected in significantly higher rates of service retention for home treatment compared with standard hospital treatment.11,17 This issue is central to good psychiatric practice.

Other advantages

There are rich descriptive and conceptual studies of the widely differing impact of hospital admission or home treatment on the lives and experience of patients and their families during an acute episode.21–23 Avoiding admission to hospital provides a critical opportunity to alter for the better the personal set of meanings surrounding mental illness and to impact on the trajectory and personal narrative of the psychiatric patient's experience of his or her illness. These meanings attract powerful emotions and can affect the patient's clinical condition and become inseparable from the individual's life history.24

Problems of implementation

Since the research evidence points in its favour, why has implementation of home treatment in the United Kingdom been delayed? Mosher believed that early opposition in the United States resulted from resistance to change and a desire to protect vested interests within the medical profession.25 UK research reports which view home treatment positively have commonly been accompanied by critical editorials written by those with no clinical experience in this area.26,27 These critiques reflect the polarised debate around an unhelpful dichotomy between hospital and community care. They highlight issues which are discussed and refuted below.

Specific criticisms

Burnout among staff

Until recently there has been no research at all on the phenomenon of burnout in members of home treatment teams. This lack of evidence has not, however, stemmed speculation. Minghella et al found low levels of burnout and significantly higher job satisfaction in home treatment teams compared with results from a previous large study of community mental health nurses and ward based staff.12

Homicide and suicide

In the 25 years since home treatment became reality, there has been only one reported instance of homicide carried out by a patient who was participating in an experimental home treatment initiative.10 All the other homicides perpetrated by psychiatric patients over this period occurred while they were being treated by other parts of the mental health service. The most recent meta-analysis concurs with previous reviews—it finds no evidence for higher rates of suicide or deliberate self harm in patients having home treatment compared with hospital care.17 The risks of suicide and homicide remain a critical issue in the decision to admit patients to hospital when there are other options. However, recommendations for admitting these patients have been advanced in the published reports on home treatment.5

Sustainable and generalisable

It has been claimed that home treatment is not generalisable or sustainable. In Madison, Wisconsin, and in Sydney, Australia, model home treatment programmes are still going strong after 20 and 17 years respectively. The Madison model, which included a mental health crisis team, has had a major impact on US psychiatric care. After the Sydney initiative, emergency mobile psychiatric teams were developed in several Australian states. In north Birmingham, the availability of home treatment has expanded so much that it is the first line of response for psychiatric emergencies in a population of over half a million.

Conclusions

Negative editorial propaganda is not the sole reason for delayed implementation of home treatment in the United Kingdom. We suspect that the rapid developments in community psychiatry involving closure of institutions; cuts in numbers of psychiatric beds; and a high profile culture of blame after tragic, untoward events have created the sort of environment that promotes the more defensive practice of psychiatry. It is worth remembering that these most unfortunate events have occurred even though home treatment is not widely available.

Sophisticated evaluation of the clinical and other factors that determine admission to hospital with acute psychiatric illness remains a neglected area in the United Kingdom compared with the United States.28,29 As clinicians faced with the daily decision to admit or not, we believe that the availability of home treatment allows us to scrutinise the factors influencing this decision in a more refined way. We mostly decide on home treatment as the preferred option to hospital admission, but we also recognise when this is not a safe or feasible alternative. It is our experience that the availability of home treatment in parallel with hospital admission means that beds are readily available (rather than too few) when we need them. This further promotes safe practice. Rapid response alleviates suffering and stems the patient's clinical deterioration and the social escalation that commonly dictate admission to hospital. Finally, while endorsing home treatment in its own right, we also emphasise that its ultimate usefulness is within the context of an integrated comprehensive community strategy that includes assertive outreach provision.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Department of Health. Modernising mental health services. London: Stationery Office; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Monitoring Inner London Mental Illness Services Project Group. Monitoring inner London mental illness services. Psychiatr Bull. 1995;19:276–280. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marshall M. London's mental health service in crisis. BMJ. 1997;314:246. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7076.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deahl M, Turner T. General psychiatry in no man's land. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;171:6–8. doi: 10.1192/bjp.171.1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stein LI, Test MA. Alternative to mental hospital treatment. Conceptual model, treatment program, and clinical evaluation. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1980;37:392–397. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1980.01780170034003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fenton FR, Tessier L, Struening ELA. A comparative trial of home and psychiatric hospital care; one year follow up. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1979;36:1073–1079. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1979.01780100043003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pasaminick B, Scarpetti FR, Dinitz S. Schizophrenia in the community: an experimental model in the prevention of hospitalisation. New York: Appleton Century Crofts; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoult J. Community care of the acutely mentally ill. Br J Psychiatry. 1986;149:137–144. doi: 10.1192/bjp.149.2.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Polak PR, Kirby MW. A model to replace psychiatric hospitals. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1976;162:13–22. doi: 10.1097/00005053-197601000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muijen M, Marks IM, Connolly J, Audini B. Home-based care versus standard hospital-based care with severe mental illness: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 1992;304:749–754. doi: 10.1136/bmj.304.6829.749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dean C, Phillips J, Gadd EM, Joseph M, England S. Comparison of community based service with hospital based service for people with acute, severe psychiatric illness. BMJ. 1993;307:473–476. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6902.473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Minghella E, Ford R, Freeman T, Hoult J, McGlynn P, O'Halloran P. Open all hours. 24-hour response for people with mental health emergencies. London: Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Braun P, Kochansky G, Shapiro R, Greenberg S, Gudeman J, Johnson S, et al. Overview: deinstitutionalisation of psychiatric patients; a critical review of outcome studies. Am J Psychiatry. 1981;138:736–749. doi: 10.1176/ajp.138.6.736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kiesler CA. Mental hospitals and alternative care. Am Psychol. 1982;37:349–360. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.37.4.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kliuter H. In-patient treatment and care arrangements to replace or avoid it—searching for an evidence based balance. Curr Opinion Psychiatry. 1997;10:160–167. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Szmukler GI. Alternatives to hospital treatment. Curr Opinion Psychiatry. 1990;3:273–277. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joy CB, Adams CE, Rice K. Cochrane Library. Issue 4. Oxford: Update Software; 1998. Crisis intervention for severe mental illness. In: Cochrane Collaboration. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scott RD. A family orientated psychiatric service to the London Borough of Barnet. Health Trends. 1980;12:65–68. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Audini B, Marks IM, Lawrence RE, Connolly J, Watts V. Home-based versus out-patient/in-patient care for people with serious mental illness. Phase II of a controlled study. Br J Psychiatry. 1994;165:204–210. doi: 10.1192/bjp.165.2.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Young L, Reynolds I. Evaluation of selected psychiatric admission wards. Report for the New South Wales Health Commission. Sydney: NSW Department of Health; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Polak P. The crisis of admission. Soc Psychiatry. 1967;2:150–157. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Querido A. The shaping of community health care. Br J Psychiatry. 1968;114:293–302. doi: 10.1192/bjp.114.508.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smyth M, Bracken P. Senior registrar training and home treatment. Psychiatr Bull. 1994;18:408–409. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kleinman A. The illness narratives. New York: Basic Books; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mosher LR. Alternatives to psychiatric hospitalisation. Why has research failed to be translated into practice? N Engl J Med. 1983;309:1579–1580. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198312223092512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coid J. Failure in community care: psychiatry's dilemma. BMJ. 1994;308:805–806. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6932.805a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dedman P. Home treatment for psychiatric disorder. BMJ. 1993;306:1359–1360. doi: 10.1136/bmj.306.6889.1359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marson DC, McGovern MP, Hyman CP. Psychiatric decision making in the emergency room: a research overview. Am J Psychiatry. 1988;145:918–925. doi: 10.1176/ajp.145.8.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rabinowitz DSW, Massad MSW, Fennig MD. Factors influencing disposition decisions for patients seen in a psychiatric emergency service. Psychiatr Serv. 1995;46:712–718. doi: 10.1176/ps.46.7.712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]