Editor—In their study on the prospective risk of unexplained stillbirth in singleton pregnancies at term Cotzias et al performed a secondary analysis1 of data that we published.2 The proposed rationale for this mathematical exercise was that no published data provide accurate gestation-specific risks of stillbirth at term. In fact, our publication evaluates risks of stillbirth and neonatal and infant mortality throughout pregnancy.2

The original data for the North East Thames region, with the addition of births for 1992, were used to inform the confidential inquiry into stillbirths and deaths in infancy (CESDI) concerning antepartum stillbirths (L Hilder and N Datta, unpublished data). When both fetal and neonatal causes cited on stillbirth registrations were used the proportion of stillbirths that are unexplained increased from 0.1392 at 37 weeks to 0.5000 at 43 weeks. Even if stillbirth is explainable it is not necessarily preventable and is inevitably unexpected. We acknowledge that when doctors deal with parents who have had a recent stillbirth, information on aetiology is invaluable. We continue to believe, however, that when prospective risks are being estimated for clinical purposes all stillbirths should be included.

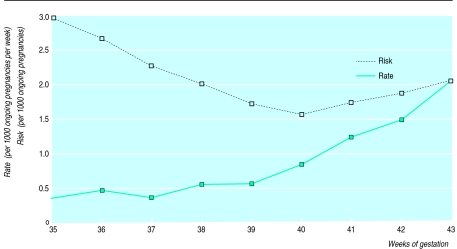

The results presented by the authors are critically flawed by the reliance on cumulative prospective risk of stillbirth. The authors total the number of stillbirths in the remaining weeks of pregnancy in order to estimate the prospective risk of stillbirth at a specific week of gestation. This methodology produces clinically implausible results, explaining the authors' paradoxical conclusion that the risk of stillbirth at 38 weeks is greater than that at 42 weeks. If this was taken to absurdity their prospective risk of stillbirth at 24 weeks would be 1 in 330 while that at 43 weeks would be 1 in 633.

We analysed data from 158 945 singleton pregnancies in the North East Thames region in which the fetuses were congenitally normal (table). Our data give clinically relevant estimates of prospective weekly risk of stillbirth, showing a sharp increase in risk after 40 weeks. Current strategies of elective induction of labour after 41 weeks seek to avert fetal death without increasing rates of obstetric intervention. Until large enough trials are performed to justify this course of management the correct interpretation of observational data from large population based analysis is vital.

Table.

Prospective risk of stillbirth by week of gestation for singleton pregnancies in North East Thames region, 1989-91

| Gestation (weeks) | No of ongoing pregnancies | No of stillbirths | Risk of stillbirth/1000 ongoing pregnancies (95% CI) | Risk of stillbirth in ensuing week |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 35 | 161 638 | 48 | 0.30 (0.23 to 0.37) | 1:3332 |

| 36 | 159 723 | 62 | 0.39 (0.31 to 0.46) | 1:2536 |

| 37 | 155 791 | 47 | 0.30 (0.23 to 0.37) | 1:3332 |

| 38 | 147 631 | 77 | 0.52 (0.44 to 0.60) | 1:1922 |

| 39 | 126 448 | 62 | 0.49 (0.40 to 0.58) | 1:2039 |

| 40 | 93 539 | 81 | 0.87 (0.80 to 0.96) | 1:1148 |

| 41 | 39 245 | 50 | 1.27 (0.94 to 1.60) | 1:786 |

| 42 | 10 305 | 16 | 1.55 (0.93 to 2.78) | 1:644 |

| 43 | 1 874 | 4 | 2.13 (0.28 to 3.99) | 1:486 |

References

- 1.Cotzias CS, Paterson-Brown S, Fisk NM. Prospective risk of unexplained stillbirth in singleton pregnancies at term: population based analysis. BMJ. 1999;319:287–288. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7205.287. . (31 July.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hilder L, Costeloe K, Thilaganathan B. Prolonged pregnancy: evaluating gestation-specific risks of fetal and infant mortality. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1998;105:169–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1998.tb10047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]