Abstract

-

»

Tumors of the brachial plexus are uncommon and can present as a mass, with or without neurological symptoms. At times, asymptomatic tumors are also picked up incidentally when imaging is performed for other reasons.

-

»

Magnetic resonance imaging is the main imaging modality used to evaluate tumors of the brachial plexus. Other imaging modalities can be used as required.

-

»

Benign tumors that are asymptomatic should be observed. Excision can be considered for those that are found to be growing over time.

-

»

Biopsies of tumors of the brachial plexus are associated with the risk of nerve injury. Despite this, they should be performed for tumors that are suspected to be malignant before starting definitive treatment.

-

»

For malignant tumors, treatment decisions should be discussed at multidisciplinary tumor boards, and include both the oncology and peripheral nerve surgical team, musculoskeletal radiology, neuroradiology, and general radiology.

Less than 5% of upper extremity tumors originate from the brachial plexus. The true incidence, however, is not known, since there may be many small, asymptomatic lesions that are not detected or reported. However, a significant proportion (about one-third) of peripheral nerve tumors involve the brachial plexus1-3. This is possibly because of the large nerve volume contained in the plexus.

Within this structure, the tumors can be intrinsic, arising from nerve tissue, or they can be extrinsic, arising from the surrounding tissue. Cancers affecting the brachial plexus can also arise from adjacent organs such as the breasts, lungs, or lymph nodes. One example is the Pancoast tumor, which was first described by Hare in 1838 as “a tumor affecting certain nerves.”4,5 The last etiology is metastatic—though this is rare, these tumors can arise from almost any primary tumor site. A variant of metastatic tumors, neurolymphomatosis, where the peripheral nerves are involved in patients with advanced lymphoma, can also arise within the brachial plexus6.

In a systematic review by Shekouhi and Chim7, 91% of brachial plexus tumors reported were benign while 9% were malignant. Among the benign tumors, the majority were schwannomas (61%) and neurofibromas (18%), with a smaller number of other types of tumors like lipomas, desmoid tumors, and hemangiomas. Most malignant tumors were malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNSTs), comprising 7% of all tumors of the brachial plexus while other malignant tumors like synovial sarcomas and lymphomas were also described. Most of the lesions were found to originate in the supraclavicular region (70%)7.

Clinical Presentation

Patients with tumors of the brachial plexus tend to present in middle age, 41.7 ± 8.7 years (range, 1-92 years), with a slight female preponderance. 11.5% have a history of neurofibromatosis. The most common clinical symptom is swelling (65%), followed by neural symptoms such as paresthesias (47%), sensory deficits (48%), and motor deficits (19%).

Patients with malignant tumors tend to have bigger tumors (>5 cm) that are fast growing, and because of their invasive nature, they tend to have neurological deficits more frequently at the time of presentation. Treatment is often delayed, with the mean duration of symptoms before medical intervention of 25.2 ± 12.3 months7.

There are also patients who present after tumors are incidentally picked up (“incidentalomas”) on imaging performed to evaluate other conditions. These tumors are almost always asymptomatic.

Workup and Diagnosis

Imaging Studies

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the mainstay of imaging for soft-tissue tumors. Some of the findings for schwannomas include a round or fusiform shape and eccentric location in the nerve. They appear isointense or slightly hyperintense to the skeletal muscle on T1 sequences and hyperintense on T2-weighted images. By contrast, neurofibromas tend to occupy a central location within the nerve and frequently exhibit a target sign on T2 sequences, with low-signal intensity in the center and a peripheral rim of higher signal intensity (though the target sign is not unique to neurofibromas). Neurofibromas also exhibit a predominantly central enhancement pattern after contrast injection. Cystic or hemorrhagic changes are less commonly seen in neurofibromas compared with schwannomas. Additional MRI methods like diffusion-weighted imaging can also be helpful in differentiating between schwannomas and neurofibromas8,9.

Ultrasound imaging is useful in differentiating between benign and malignant tumors of the brachial plexus. Benign tumors tend to be well defined and without associated peritumoral edema. They also exhibit either no or homogeneous enhancement after contrast injection. Malignant tumors tend to be poorly defined. Peritumoral edema is frequently seen, as well as central necrosis and hemorrhage. They also exhibit heterogeneous enhancement with contrast8,10.

Another modality that can help in this critical diagnostic differentiation is 18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography scans. Malignant tumors tend to have higher metabolic activity, which is reflected by a higher maximum standardized uptake value. The cutoff level between benign and malignant tumors is still a matter of debate. However, when used in conjunction with other imaging modalities like MRI scans, the diagnostic accuracy is improved11.

In patients with type 1 neurofibromatosis, sequential imaging may be required, due to the higher risk of developing malignancies, need to monitor multiple nerve sheath tumors, and the poorer survival prognosis for these patients12.

Role of Biopsy

It is not uncommon for a diagnosis to remain indeterminate after imaging13. Since there is a big difference between the treatment approaches for benign and malignant tumors, and also between different types of malignant tumors, it is important to establish a clear working diagnosis before initiating treatment. Biopsies of the brachial plexus are challenging as they have the dual risk of damage to a nerve, and the difficulty and unpredictability of operating in a field where there is possible malignant tissue. While there is a risk of contamination of the surgical field and compromising the outcome for the patient during all biopsies14, this is especially critical in the brachial plexus. Balancing all these factors, it may be better in some cases, especially where the suspicion of malignancy is low, to opt for close observation and early repeat imaging, rather than intervening immediately. Conversely, should the suspicion of malignancy be high, then it is better to proceed with a biopsy to get a definitive diagnosis before treatment is initiated.

It is tempting to proceed with a marginal excision of the mass, given the concerns of both avoiding progression of the tumor, and avoiding multiple procedures for the patient when performing a biopsy alone. However, a bigger morbidity can be caused when incomplete excision of a malignant tumor is performed. The resultant contamination of the surgical field will make subsequent surgical clearance very difficult, possibly converting a salvageable situation into one that is not15,16. Hence, it is important that these cases be discussed at multidisciplinary team meetings before a decision on biopsy or surgical excision is made.

Treatment Strategy

A summary of the treatment strategy for the various tumor types is provided in Table I.

TABLE I.

Treatment of Brachial Plexus Tumors*

| Tumor Type | Considerations | Suggested Treatment |

|---|---|---|

| Benign | ||

| Intrinsic | ||

| Schwannoma | Marked increase in size/worsening neurological deficit | Marginal excision |

| Stable size/minimal neurological deficit | Observation | |

| Neurofibroma | Marked increase in size, severe neurological deficit | Excision possible reconstruction |

| Stable size/nonprogressive neurological deficit | Observation | |

| Perineurioma | Observation unless there is marked progression | |

| Lipofibromatous hamartoma | Observation unless there is marked progression | |

| Extrinsic | ||

| Lipoma | Observation unless there is marked progression/suspicion of atypical lipomatous tumor | |

| Hemangioma | Observation unless there is marked progression | |

| Desmoid tumor | Discussion at MTB. Observation unless there is marked progression—to consider nonsurgical options as well | |

| Malignant | ||

| Intrinsic | ||

| MPNST | Discussion at MTB. Consider neoadjuvant radiotherapy before resection | |

| Extrinsic | ||

| Other sarcomas | Discussion at MTB. Consider neoadjuvant radiotherapy before resection | |

| Other malignant tumors | Discussion at MTB. Treatment dependent on symptoms and cancer type |

MPNST = malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor, and MTB = multidisciplinary tumor board.

Benign Tumors

Many benign tumors, especially those that are asymptomatic and/or are picked up incidentally, can be observed. Schwannomas, which are the most common tumors, may not need to be excised unless they are causing significant functional deficits or when there is a significant rate of growth.

Lubelski et al. found that solitary schwannomas tend to fall into slow or fast growing categories. Sequential imaging makes extrapolation of the rate of growth of the tumor possible, and this guides the decision for surgery. Size alone is not a definite indication for surgery3.

When required, schwannomas can be excised using techniques that lower the risk of neural morbidity. In most of the cases, with control of the proximal and distal aspects of the involved nerve, complete excision can be performed by sharp separation under magnification from the surrounding fascicles, preserving the uninvolved fascicles.

Neurofibromas, on the other hand, can only rarely be completely excised without deficits, and the balance between the morbidity of surgery and the desire for complete removal needs to be considered. Neurofibromas tend to involve more nerve fascicles, and excision is not possible without their sacrifice. Should these fascicles serve important functions, significant morbidity for the patient will result. Selective sacrifice of nerves is possible in the course of an excision when intraoperative nerve stimulation is used. Occasionally, subtotal excision of a benign tumor may need to be performed to preserve function2,17. Hence, careful consideration needs to be taken when deciding whether to attempt excision of a neurofibroma—often, it may be better not to excise the tumor and accept the symptoms and/or nerve deficit.

Low recurrence rates are seen in patients with schwannomas and neurofibromas following gross total resection2,17,18. Most experience improvements clinically, with decreased pain and improved sensation, even if gross total resection was not achieved. However, approximately 15% still reported persistent or significant pain2,18, while up to 25% reported worsened motor function following surgery18.

When a deficit occurs, reconstruction with nerve transfers, tendon transfers, or nerve grafting should be part of the treatment plan communicated to the patient. It is not often that this can be anticipated; hence, reconstruction will need to be performed in a staged manner. The exact technique of reconstruction used will depend on the deficit encountered.

The treatment of benign extrinsic tumors follow similar principles and are also determined by the primary pathology. For example, lipomas and hemangiomas can also be excised without deficits.

Malignant Tumors

For malignant tumors, the aim of treatment is focused on the preservation of life followed by salvage of the limb. There are different treatment options for different malignant tumors; hence, it is recommended that a biopsy be performed, despite the risks, so that a definite diagnosis can be established, before definitive treatment.

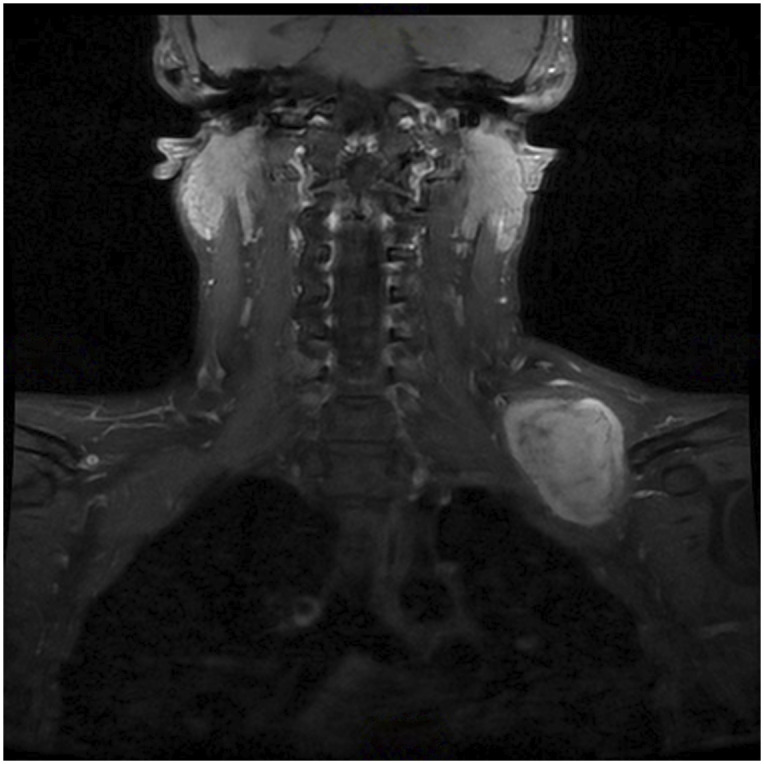

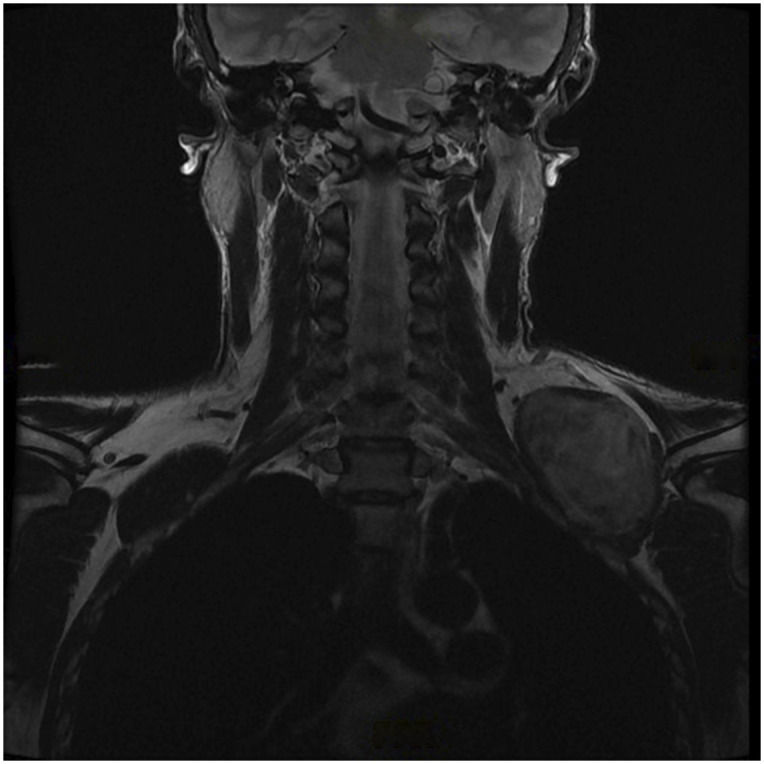

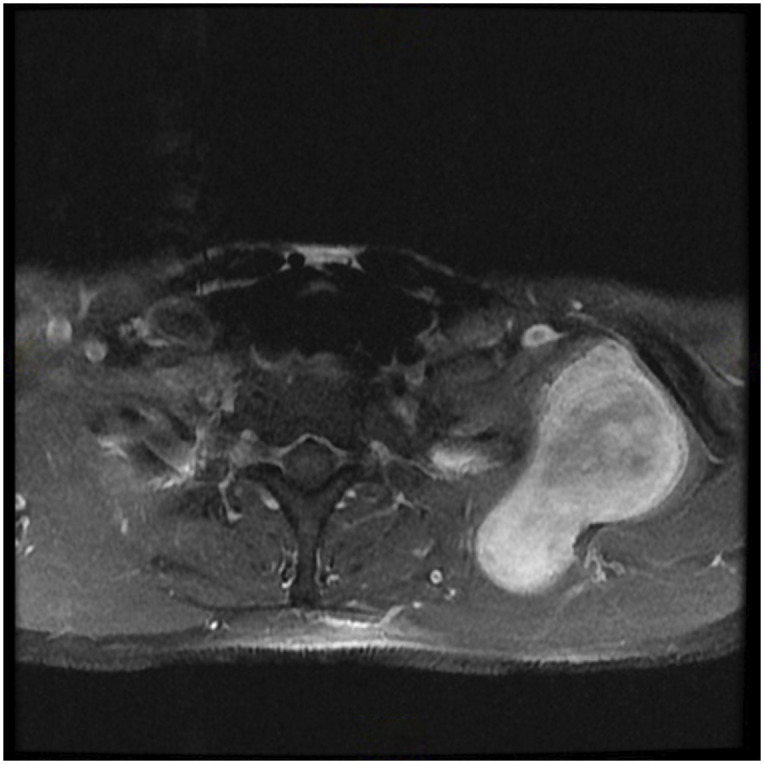

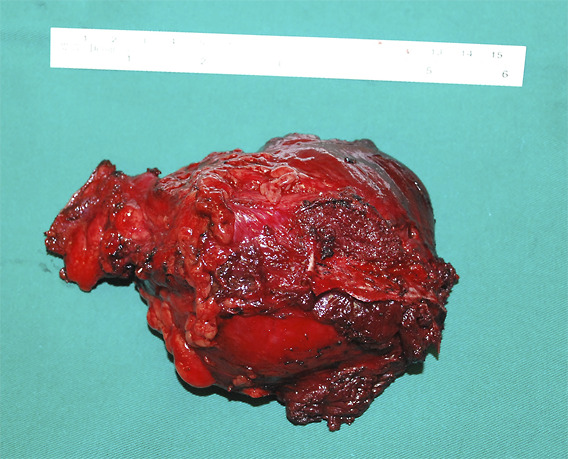

MPNSTs are the most commonly encountered malignant tumors in the brachial plexus. The best outcomes for MPNSTs and other sarcomas are achieved with complete resection of the tumor19,20. An example of the management of such a case is illustrated in Figures 1, 2, and 3.

Figs. 1-A, 1-B, and 1-C MRI images showing a soft-tissue mass around the brachial plexus. A core biopsy was performed, and histology showed a synovial sarcoma. MRI = magnetic resonance imaging.

Fig. 1-A.

Fig. 1-B.

Fig. 1-C.

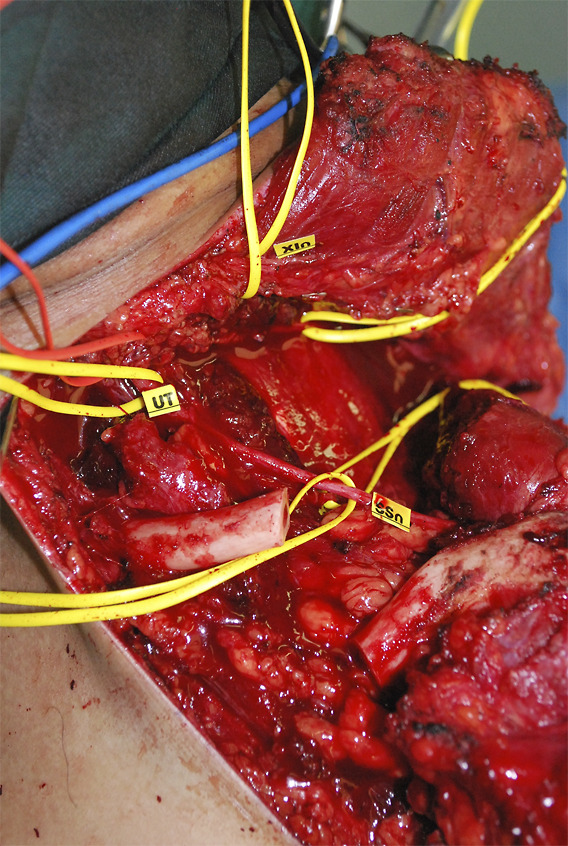

Fig. 2.

Wide excision of the mass was performed. The surgical approach required osteotomy of the clavicle.

Fig. 3.

Complete excision with clear margins was achieved. The patient had no neurological deficits after surgery and underwent postoperative radiotherapy. He remained disease-free 6 years after treatment and was subsequently lost to follow-up.

There is conflicting data about benefit of both radiotherapy and chemotherapy19-23, and the decision on the appropriate treatment for each patient should be discussed at a multidisciplinary tumor board.

Despite the difficulties created during surgery, our preferred option for MPNSTs (and other high grade sarcomas) is for preoperative radiotherapy, followed by complete resection of the tumor. If intraplexal reconstruction is required, then it can be performed at the same time as tumor resection, since attempting to do so in a staged manner following preoperative radiotherapy is expected to be extremely difficult.

For lymphomas, surgery is generally not required, with chemotherapy and radiotherapy being the main modalities used. For extrinsic malignancies, there may be a benefit in excising tumors arising from adjacent organs that abut and compress the brachial plexus. However, we have not found any benefit for surgery in patients where there is evidence of direct invasion causing neurological deficits. When there is interfascicular spread of the tumor, w nerve-preserving excision is not possible. In patients with advanced local disease with no evidence of distant metastases, options like forequarter amputations can be considered.

In patients with metastatic disease, resection of the tumor is not possible or required, and maximal efforts should be made to manage symptoms and pain.

A summary of the recommendations for care is presented in Table II.

TABLE II.

Recommendations for Care in Patients with Brachial Plexus Tumors*

| Recommendations | Grade of Evidence† |

|---|---|

| Imaging for brachial plexus tumors | |

| MRI | B |

| Ultrasound | B |

| 18-FDG PET scans | B |

| Role of biopsy in diagnosis of brachial plexus tumors | I |

| Conservative excision for benign brachial plexus tumors | C |

| Wide excision for sarcomas involving the brachial plexus | C |

| Adjuvant treatment (radiotherapy and chemotherapy) for MPNSTs | I |

18-FDG PET = 18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography, MPNST = malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor, and MRI = magnetic resonance imaging.

According to Wright24, grade A indicates good evidence (Level I studies with consistent findings) for or against recommending intervention; grade B, fair evidence (Level II or III studies with consistent findings) for or against recommending intervention; grade C, poor-quality evidence (Level IV or V studies with consistent findings) for or against recommending intervention; and grade I, insufficient or conflicting evidence not allowing a recommendation for or against intervention.

Conclusion

The treatment of brachial plexus tumors is dependent on the diagnosis, severity of symptoms, and rate of growth. Benign tumors that are asymptomatic and picked up incidentally should be observed while those that are growing and/or causing severe symptoms may need to be excised or debulked. In cases where the diagnosis is not clear, observation with sequential imaging can be considered before a biopsy or excision. Finally, for tumors that are more likely malignant, a biopsy and discussion at a multidisciplinary tumor board before starting definitive treatment is recommended.

Sources of Funding

No funding was provided in the investigation of this study.

Footnotes

Investigation performed at the National University Hospital, Singapore

Disclosure: The Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest forms are provided with the online version of the article (http://links.lww.com/JBJSREV/B108).

References

- 1.Kim DH, Murovic JA, Tiel RL, Moes G, Kline DG. A series of 397 peripheral neural sheath tumors: 30-year experience at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center. J Neurosurg. 2005;102(2):246-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Desai KI. The surgical management of symptomatic benign peripheral nerve sheath tumors of the neck and extremities: an experience of 442 cases. Neurosurgery. 2017;81(4):568-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lubelski D, Pennington Z, Ochuba A, Azad TD, Mansouri A, Blakeley J, Belzberg AJ. Natural history of brachial plexus, peripheral nerve, and spinal schwannomas. Neurosurgery. 2022;91(6):883-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hare E. Tumor involving certain nerves. London Med Gazette. 1838(1):16-8. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pancoast HK. Importance of careful roentgen-ray investigations of apical chest tumors. JAMA. 1924;83(18):1407-11. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foo TL, Yak R, Puhaindran ME. Peripheral nerve lymphomatosis. J Hand Surg Asian Pac Vol. 2017;22(1):104-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shekouhi R, Chim H. Patient demographics, tumor characteristics, and outcomes following surgical treatment of benign and malignant brachial plexus tumors: a systematic review. Int J Surg. 2023;109(4):972-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lefebvre G, Le Corroller T. Ultrasound and MR imaging of peripheral nerve tumors: the state of the art. Skeletal Radiol. 2023;52(3):405-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yun JS, Lee MH, Lee SM, Lee JS, Kim HJ, Lee SJ, Chung HW, Lee SH, Shin MJ. Peripheral nerve sheath tumor: differentiation of malignant from benign tumors with conventional and diffusion-weighted MRI. Eur Radiol. 2021;31(3):1548-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Winter N, Dohrn MF, Wittlinger J, Loizides A, Gruber H, Grimm A. Role of high-resolution ultrasound in detection and monitoring of peripheral nerve tumor burden in neurofibromatosis in children. Childs Nerv Syst. 2020;36(10):2427-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Broski SM, Johnson GB, Howe BM, Nathan MA, Wenger DE, Spinner RJ, Amrami KK. Evaluation of (18)F-FDG PET and MRI in differentiating benign and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Skeletal Radiol. 2016;45(8):1097-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lim Z, Gu TY, Tai BC, Puhaindran ME. Survival outcomes of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNSTs) with and without neurofibromatosis type I (NF1): a meta-analysis. World J Surg Oncol. 2024;22(1):14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Papp DF, Khanna AJ, McCarthy EF, Carrino JA, Farber AJ, Frassica FJ. Magnetic resonance imaging of soft-tissue tumors: determinate and indeterminate lesions. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(suppl 3):103-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mankin HJ, Mankin CJ, Simon MA. The hazards of the biopsy, revisited. Members of the Musculoskeletal Tumor Society. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78(5):656-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Noria S, Davis A, Kandel R, Levesque J, O'Sullivan B, Wunder J, Bell R. Residual disease following unplanned excision of soft-tissue sarcoma of an extremity. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78(5):650-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Donaldson EK, Winter JM, Chandler RM, Clark TA, Giuffre JL. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors of the brachial plexus: a single-center experience on diagnosis, management, and outcomes. Ann Plast Surg. 2023;90(4):339-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jia X, Yang J, Chen L, Yu C, Kondo T. Primary brachial plexus tumors: clinical experiences of 143 cases. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2016;148:91-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pisapia JM, Adeclat G, Roberts S, Li YR, Ali Z, Heuer GG, Zager EL. Tumors of the brachial plexus region: a 15-year experience with emphasis on motor and pain outcomes and literature review. Surg Neurol Int. 2023;14:162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martin E, Coert JH, Flucke UE, Slooff WBM, Ho VKY, van der Graaf WT, van Dalen T, van de Sande MAJ, van Houdt WJ, Grünhagen DJ, Verhoef C. A nationwide cohort study on treatment and survival in patients with malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours. Eur J Cancer. 2020;124:77-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roohani S, Claßen NM, Ehret F, Jarosch A, Dziodzio T, Flörcken A, Märdian S, Zips D, Kaul D. The role of radiotherapy in the management of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors: a single-center retrospective cohort study. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2023;149(20):17739-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alektiar KM, Brennan MF, Healey JH, Singer S. Impact of intensity-modulated radiation therapy on local control in primary soft-tissue sarcoma of the extremity. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(20):3440-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kroep JR, Ouali M, Gelderblom H, Le Cesne A, Dekker TJA, Van Glabbeke M, Hogendoorn PCW, Hohenberger P. First-line chemotherapy for malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST) versus other histological soft tissue sarcoma subtypes and as a prognostic factor for MPNST: an EORTC soft tissue and bone sarcoma group study. Ann Oncol. 2011;22(1):207-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Widemann BC, Lu Y, Reinke D, Okuno SH, Meyer CF, Cote GM, Chugh R, Milhem MM, Hirbe AC, Kim A, Turpin B, Pressey JG, Dombi E, Jayaprakash N, Helman LJ, Onwudiwe N, Cichowski K, Perentesis JP. Targeting sporadic and neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) related refractory malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNST) in a phase II study of everolimus in combination with bevacizumab (SARC016). Sarcoma. 2019;2019:7656747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wright JG. Revised grades of recommendation for summaries or reviews of orthopaedic surgical studies. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(5):1161-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]