Abstract

Background:

The global burden of trauma disproportionately affects low-income countries and middle-income countries (LMIC), with variability in trauma systems between countries. Military and civilian healthcare systems have a shared interest in building trauma capacity for use during peace and war. However, in LMICs it is largely unknown if and how these entities work together. Understanding the successful integration of these systems can inform partnerships that can strengthen trauma care. This scoping review aims to identify examples of military-civilian trauma systems integration and describe the methods, domains, and indicators associated with integration including barriers and facilitators.

Methods:

A scoping review of all appropriate databases was performed to identify papers with evidence of military and civilian trauma systems integration. After manuscripts were selected for inclusion, relevant data was extracted and coded into methods of integration, domains of integration, and collected information regarding indicators of integration, which were further categorized into facilitators or barriers.

Results:

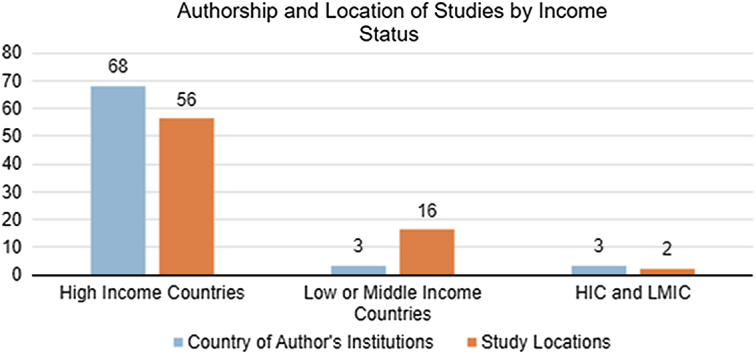

Seventy-four studies were included with authors from 18 countries describing experiences in 23 countries. There was a predominance of authorship and experiences from High-Income Countries (91.9 and 75.7%, respectively). Five key domains of integration were identified; Academic Integration was the most common (45.9%). Among indicators, the most common facilitator was administrative support and the lack of this was the most common barrier. The most common method of integration was Collaboration (50%).

Conclusion:

Current evidence demonstrates the existence of military and civilian trauma systems integration in several countries. High-income country data dominates the literature, and thus a more robust understanding of trauma systems integration, inclusive of all geographic locations and income statuses, is necessary prior to development of a framework to guide integration. Nonetheless, the facilitators identified in this study describe the factors and environment in which integration is feasible and highlight optimal indicators of entry.

Keywords: global surgery, integration, military-civilian partnerships, trauma, trauma systems

Introduction

Highlights

Military-civilian integration in trauma systems occurs at varying levels: coordination, collaboration, partial integration, and full integration, with collaboration being the most common.

Five key domains of integration were identified: skills sustainment, academic integration, geographical location, event based integration, and high-level government support.

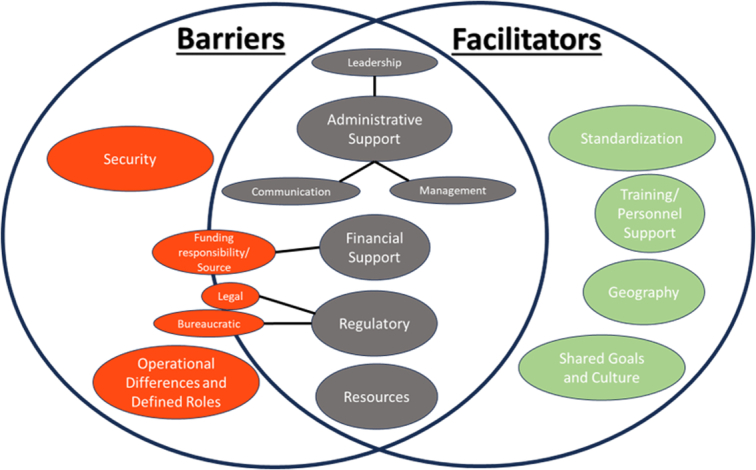

Facilitators to integration include administrative support, financial support, regulatory support, geography, training and personnel support, standardization, and shared goals and cultural bridging.

Barriers to integration include administrative, financial, regulatory, resources, security, and operational differences and defined roles.

There is a predominance of high income country literature on military-civilian partnerships in trauma care.

Trauma is a leading cause of mortality worldwide, accounting for about 4.4 million deaths per year1. Globally, trauma drives morbidity and disability, with road injuries ranking sixth in years of life lost (YLL) and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) in 20192. This is projected to worsen, with road injuries and falls projected to become the 7th and 17th leading cause of death by 2030, respectively3. Trauma disproportionately affects younger individuals, thereby reducing workforce productivity with economic ramifications that account for more productive years of work lost than other illnesses4. Furthermore, the global impact is not uniformly distributed, with up to 90% of injury-related deaths occurring in low-income countries and middle-income countries (LMICs)5.

Patient outcomes are improved when comprehensive trauma systems are available6–10. Military healthcare systems exist in over 80 countries and are invested in improving trauma care as a direct application to improving combat medicine and force sustainment11. However, the volume of traumatically injured patients treated in military facilities expands and contracts with war and peacetime. Civilian health systems perpetually provide trauma care but unless they are near active conflict, generally treat fewer patients with the complex war-related injuries seen in combat zones. In the US, a landmark report by the National Academies of Science summarized this and pointed out mutual benefit for both systems, advocating for greater integration between civilian and military trauma care12. Furthermore, growing interest in the ‘Walker Dip’, where advances in trauma care from wartime experience are lost during peacetime, has prompted more research into skills sustainment13.

Though the American College of Surgeons published guidelines for developing integration partnerships, they remain specific to the US healthcare system and largely involve embedding military teams into civilian trauma centers which has been shown to increase military experience with trauma but has not necessarily been proven to increase distribution of trauma resources nationally14. The role and application of similar military-civilian integration to support developing comprehensive trauma care in LMICs has not been systematically investigated and there are currently no internationally applicable frameworks to guide the development of these partnerships.

The IMPACT (Integrated Military Partnerships and Civilian Trauma Systems) Study aims to quantify integration globally as well as identify indicators for the ultimate aim of building a national framework of military and civilian trauma system integration that would fit within a National Surgical Obstetric and Anesthesia Plan (NSOAP)15. Phase 1 of the IMPACT Study showed that in geographically and developmentally diverse countries, despite varying cultures, there are commonalities in indicators of military and civilian trauma system integration16. This scoping review, also part of Phase 1, was designed to determine previous or ongoing integration between military and civilian trauma systems globally and to quantify indicators of integration from existing literature.

Methods

Review question

This scoping review was carried out in accordance with the guidance document developed by the Joanna Briggs Institute and the PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/JS9/C138)17,18. A copy of the protocol (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/7HKR4) can be accessed online (https://osf.io/4sp5b/). A systematic database search was conducted to answer the following research question: what evidence exists that demonstrates military and civilian trauma systems integration and describes methods, domains, and barriers and facilitators to integration?

Identifying studies

Studies reporting on military-civilian integration supporting trauma systems were identified by searching the electronic databases PubMed (NCBI), Embase (Elsevier), Web of Science Core Collection (Clarivate), CINAHL (EBSCO), Global Health (EBSCO), and the WHO’s Global Index Medicus. Additional searches were carried out in Google Scholar. The search was constructed with terms for integration or partnership, terms for military activities, and terms for emergency services (see Appendix A, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/JS9/C139). Controlled vocabulary terms were included when available. Searches were carried out in October of 2021. Studies were only included if published between January 1976 and October 2021, as these followed the end of the Vietnam War, the inception of Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS), and subsequently the systems approach to trauma care. The full inclusion/exclusion criteria are listed in Supplementary Materials (Supplemental Table 1, Supplemental Digital Content 3, http://links.lww.com/JS9/C140). The Covidence systematic review software (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia. Available at www.covidence.org) was used to conduct abstract and full-text reviews. Two authors (M.B. and E.M.) independently assessed the full text for study inclusion, with a senior author resolving conflicts. Two authors (M.B. and E.M.) independently completed this data extraction and resolved conflicts with a third senior author as needed. The reported sources of funding for the included studies are listed in Appendix B (Supplemental Digital Content 4, http://links.lww.com/JS9/C141). This scoping review was not funded.

Charting data

The data extraction was charted in Microsoft Excel Version 2302 (Microsoft). Data collected included: country of authors’ institutions, study location, design, method of integration, occurrence of a disaster or conflict, and facilitators and barriers to integration as described by the studies. The intersection of military and civilian trauma care can exist via multiple methods as described by Ratnayake et al.19 (Table 1) and these definitions were used to label the method of integration seen in each paper. Domains were identified and defined (Table 1); articles were re-examined to ensure those present in each paper were consistently identified.

Table 1.

Definitions of terms related to integration including methods and domains.

| Methods of integration | |

| Coordination | Event-based interconnectedness of two or more institutions without formal agreements |

| Collaboration | Formal agreement between two or more institutions |

| Partial integration | Interconnectedness of two or more systems at one or more levels |

| Full integration | Blending into a unified system with interconnectedness at all levels |

| Domains associated with integration | |

| Skill sustainment (Readiness) | Developing and/or maintaining skills needed for trauma care delivery for a ready military medical force |

| Academic integration (Research, training, and education) | Collaboration in academic environment promoting knowledge base through research in trauma, improving skills and care, and active educational programs |

| Geographic location | Utilization of existing local and regional trauma care resources and/or infrastructure |

| Event based integration | Use of trauma resources and/or infrastructure in response to a specific event with resulting casualties |

| High level government support | Integration and/or collaboration fostered by state/provincial or national level government bodies through means including funding, legislation, logistical support |

Adapted from Ratnayake et al., BMJ Mil Health14

Results

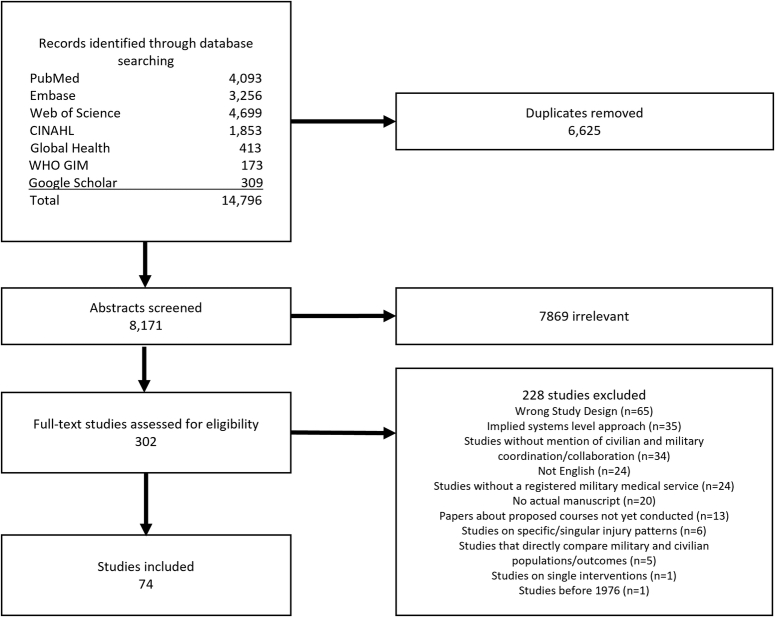

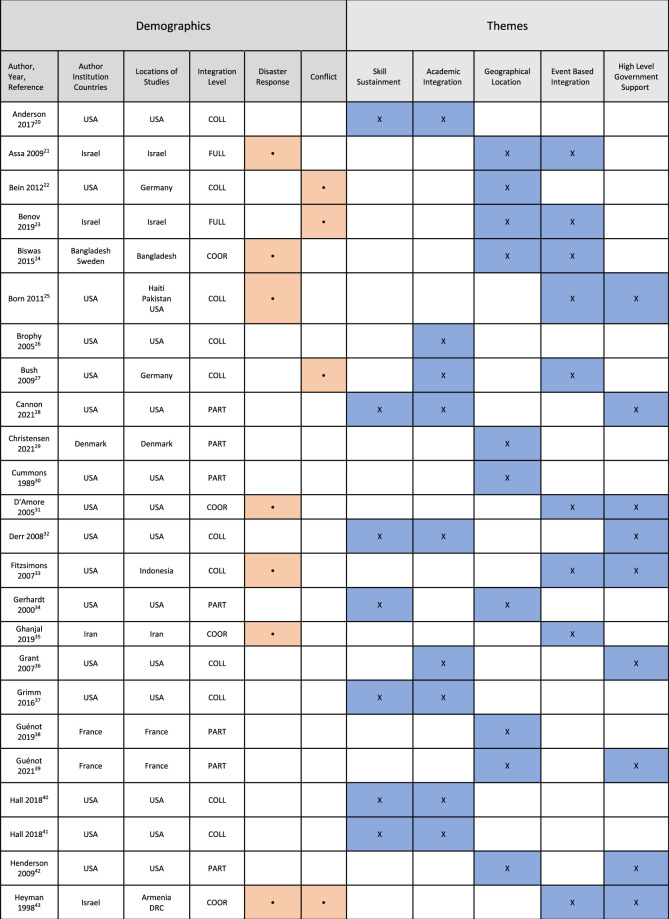

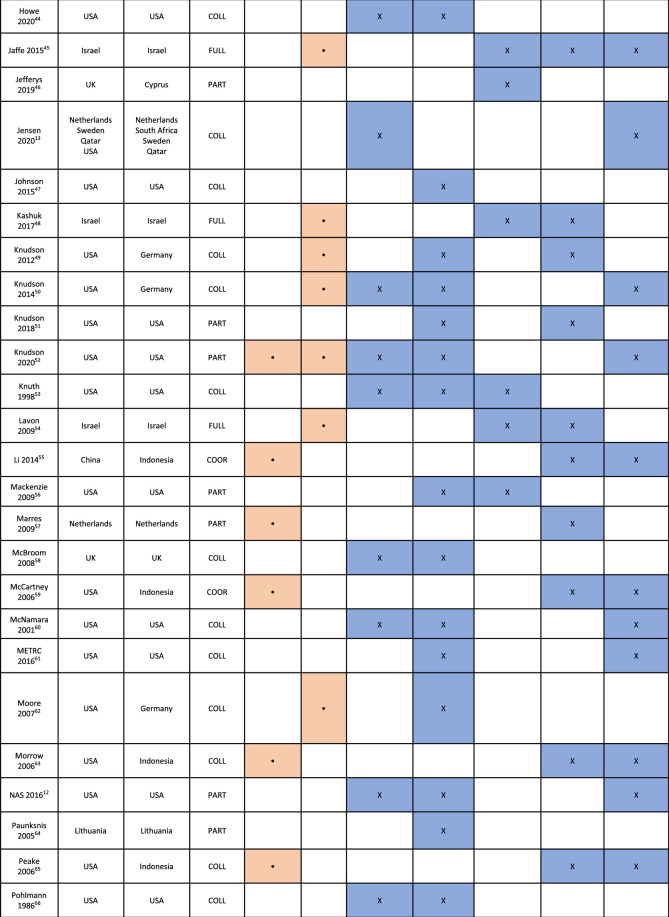

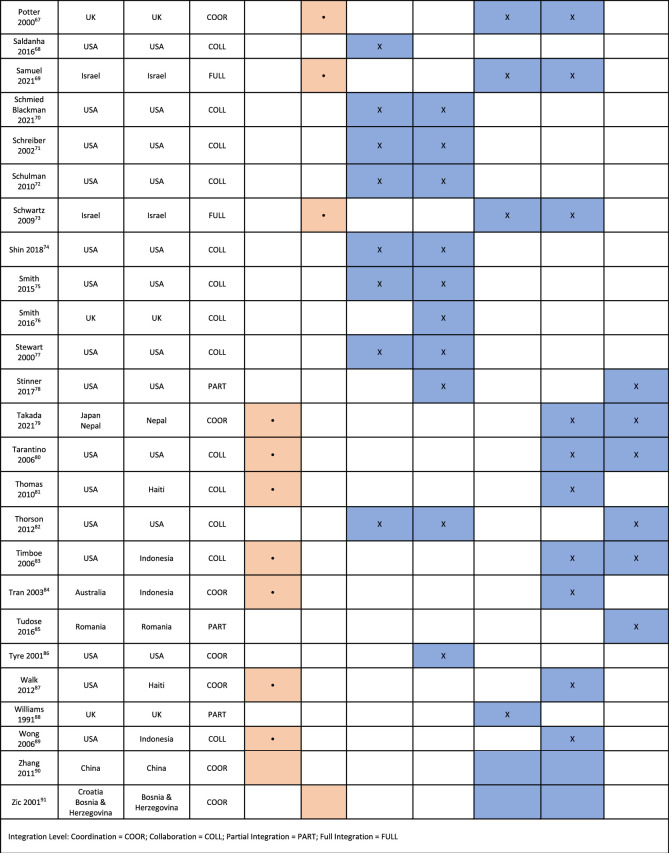

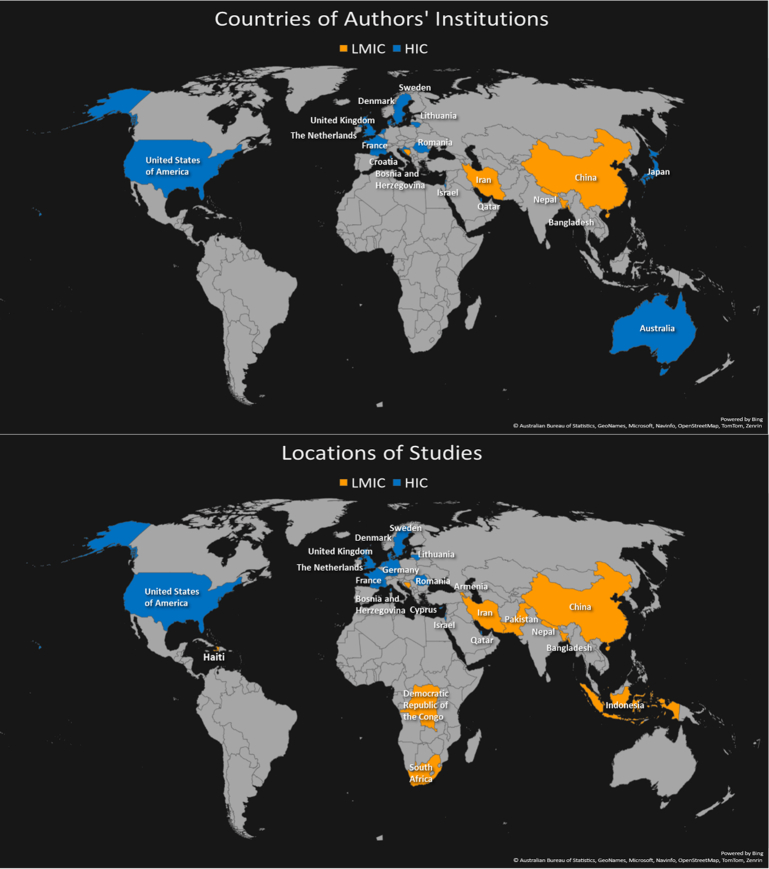

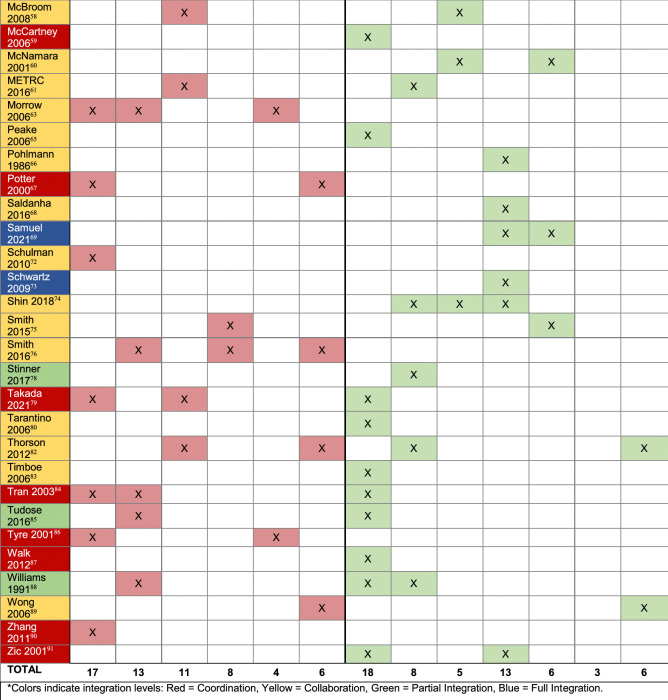

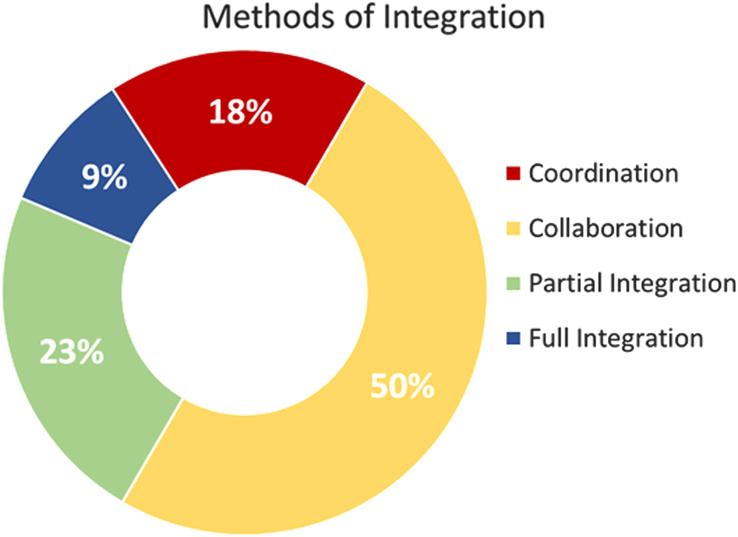

The search yielded 8171 unique publications. A total of 302 full text articles were then reviewed for inclusion, with 74 publications meeting the eligibility criteria of military and civilian integration in the context of trauma care (Fig. 1). The most common causes for exclusion were a focus on psychological trauma or describing hypothetical descriptions of military-civilian integration. Table 2 summarizes the demographics of the articles included. These 74 studies were written by authors from institutions in 18 different countries and described experiences in 23 different countries (Fig. 2). The most common method of integration was Collaboration (n=37), followed by Partial Integration (n=17), Coordination (n=13), and Full Integration (n=7), as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 1.

PRISMA-ScR Flow Diagram.

Table 2.

Summary of literature included in this scoping review and identified themes.

Integration Level: Coordination=COOR; Collaboration=COLL; Partial Integration=PART; Full Integration=FULL.

Figure 2.

Maps depicting countries of authors' institutions and locations of studies.

Figure 3.

Percentage breakdown of methods of integration seen in reviewed articles.

In total, 21 studies reported disaster response, and 15 described armed conflict as the impetus for integration. Disaster responses predominantly demonstrated Coordination (47.6%, n=10) or Collaboration (38.1%, n=8); only three demonstrated Partial Integration (9.52%, n=2) or Full Integration (4.76%, n=1). Among 15 studies involving conflict, Full Integration was most common with 40% (n=6), followed by Collaboration in 33.3% (n=5), Coordination in 20.0% (n=3), and Partial Integration in 6.67% (n=1). In two papers, responses to both disaster and conflict were reported with each paper citing multiple examples43,52. Heyman et al. described two separate examples of integration, one in response to an earthquake in what was then Soviet Armenia, the other in response to Rwandan refugees escaping to Goma in then Zaire (Democratic Republic of the Congo). Knudson described multiple examples of integration, in both disaster and conflict settings, when discussing military-civilian partnerships.

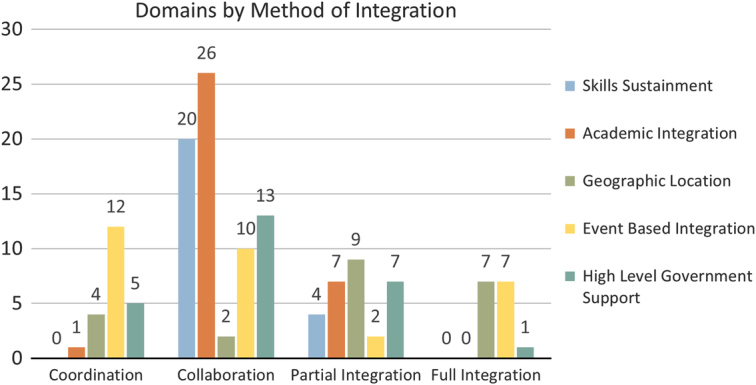

Analysis of the included articles identified five domains that were associated with integration, defined in Table 1. Academic Integration was most common, reported in 45.9% (n=34) of studies. Event Based Integration was next, described in 41.9% (n=31), followed by High-Level Government Support in 35.1% (n=26), Skill Sustainment in 32.4% (n=24), and Geographic Location in 29.7% (n=22). The full list of studies with associated domains is found in Table 2. Skills Sustainment and Academic Integration were not exclusive to physicians and included allied healthcare providers such as first responders/medics and nurses12,13,28,32,34,37,40,41,44,51,52,58,60,66,70,72,75–78,82. Studies that involved Skills Sustainment and/or training largely focused on military personnel12,13,20,27,28,32,34,37,40,41,44,49–53,58,60,62,66,68,70–72,74–78,82. The remainder involved joint military-civilian training for mass casualty events and disaster response26,36,47,56,64,83,86.

The most common domains by method of integration were Event Based Integration (Coordination), Academic Integration (Collaboration), Geographic Location (Partial Integration), and Geographic Location/Event Based Integration (Full Integration) as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Domains of integration by methods of integration.

The articles were reviewed for barriers and facilitators to effective partnerships described by their authors. Table 3 identifies indicators of integration, reported as barriers or facilitators, with Supplemental Table 2 (Supplemental Digital Content 5, http://links.lww.com/JS9/C142) containing text descriptors. A total of 39 and 44 studies described barriers and facilitators, respectively.

Table 3.

Articles describing indicators identified as barriers and/or facilitators to integration.

Colors indicate integration levels: Red=Coordination, Yellow=Collaboration, Green=Partial Integration, Blue=Full Integration.

Among barriers, indicators included Administrative (management, leadership, and communication), Financial, Regulatory (legal and bureaucratic), Resources, Security, and Operational Differences and Defined Roles. Administrative barriers included lack of cross-organizational communication, ill-defined leadership roles, and logistics. Financial limitations included inconsistent or unavailable funding sources, often nonsustained and/or unreliable. Regulatory barriers included credentialing and liability concerns. Resources encompassed differences in training, staffing levels, and resource availability. Security barriers included arranging force protection and Operational Differences involved unclear roles for military and civilian personnel in training environments.

In contrast, many indicators were found to be facilitators when present (Fig. 5). These indicators included Administrative Support (management, leadership, and communication), Financial Support, Regulatory Support, Geography, Training and Personnel Support, Standardization, and Shared Goals and Cultural Bridging. Administrative Support was described as invested leadership, facilitated communication between organizations, and support from professional organizations. Financial Support included dedicated funding streams. Regulatory Support encompassed facilitation of credentialing and liability coverage. Co-location of resources was an attribute in Geography. Training and Personnel Support were described by utilizing personnel experience and certification appropriately, allowing providers to focus on trauma skills instead of learning institution-specific tasks, and maintaining military employment in civilian settings. Standardization was identified in operational practices as well as data management. Shared Goals and Cultural Bridging included orientations to military culture for civilian personnel, sharing of best practices, and augmenting capabilities for trauma care.

Figure 5.

Indicators identified within articles related to integration noted as barriers or facilitators.

Evidence of integration was presented by institutions located in 18 different countries, with 72.2% (n=13) of those being HICs. The experiences described in the studies occurred in 23 unique countries, with 52.2% (n=12) being HICs. Authorship sources were assessed to determine the perspective of the reporting and relationship to the integration. Specifically, whether the evidence was HIC-only perspective in an LMIC, joint HIC and LMIC perspective in an LMIC, or LMIC perspective in an LMIC. Figure 6 demonstrates the breakdown of authors’ institutions and study locations by country income status. Of the 74 studies analyzed, a majority were written solely by authors from HIC institutions (91.9%, n=68) and described examples of integration taking place in HICs (75.7%, n=56). Only six studies included authors from LMIC institutions24,35,55,79,90,91. Of these, half were published in collaboration with authors from HICs, such that only three publications (4.1%) had authors solely from LMIC institutions35,55,90. Eighteen studies described experiences in LMICs13,24,25,33,35,43,55,59,63,65,79,81,83,84,87,89–91, of which only six included authors from those settings24,35,55,79,90,91.

Figure 6.

Number of studies written by authors from institutions in HIC, LMIC, or both, as well as number of studies taking place in HIC, LMIC, or both.

Seventeen of the studies describing experiences in LMICs (94.4%) described integration occurring in response to an event; disasters (n=14)24,25,33,35,43,55,59,63,65,79,81,83,87,89,90, conflict (n=2)84,91, and both disaster and conflict (n=1)43. The remaining study described Swedish surgeons traveling to South Africa for Skills Sustainment13. All three studies written entirely by LMIC authors described disaster response35,55,90. Similarly, the other three studies that included both HIC and LMIC authors described disaster response (n=2) and conflict (n=1)24,79,91.

Discussion

With the globally growing need for trauma care capacity worldwide, it is essential to study potential avenues to augment and improve trauma systems. To study the potential of military-civilian integration as an avenue, this scoping review evaluated methods of military-civilian trauma integration and tabulated 13 indicators that can be used to inform a framework (Table 3).

Methods of integration

Collaboration was the most common method followed sequentially by Partial Integration, Coordination, and Full Integration. Collaboration is defined by formal partnerships and does not involve systems interconnectedness. Therefore, it is theoretically the easiest to implement and may be the first step toward sustained integration. Some examples of Collaboration were achieved within a matter of weeks, such as when civilians from Project HOPE joined the USNS Mercy disaster response mission in 200433,63,65,83,89. Collaboration arose when a specific need could be met by an element of another system, most frequently manifesting in the domains of Skills Sustainment and Academic Integration, such as agreements for providers to work in high volume trauma centers for patient care opportunities. Coordination arose rapidly and predominantly in disaster and conflict settings. The urgent nature of the setting often precluded drafting the formal agreements that define Collaboration. Partial and Full Integration were seen where combining medical assets was part of routine trauma system function; in particular, aeromedical evacuation and prehospital care29,30,34,38,39,46,85,88.

In this review, Full Integration was only seen in Israel, a nation with a history of regular and ongoing conflict. Alswaiti et al.16 described the fully integrated Israeli trauma system where all civilian providers receive experience through obligatory military service and factors such as conflict, patriotism, and proximity to battlefronts support integration. Congruently, Geographic Location and Event Based Integration were the most common domains seen in Full Integration. These results cannot be used to infer anything about integration’s effect on patient outcomes but can demonstrate feasibility.

Of the 74 studies, 21 described responses to disaster and 15 to conflict. Militaries are well equipped to conduct operations in austere conditions requiring flexibility and adaptation; the training, personnel, and equipment appropriately translates to the disaster response setting. Additionally, the unique injury pattern associated with blasts and high-velocity firearms employed by terrorists has led to some advocating for partnerships to leverage the experience of military surgeons more familiar with severe trauma to manage violently injured civilians92. While this review focused on the integration of trauma care, military, and civilian organizations partner across the various components of disaster response93. With more severe weather events due to the effects of climate change94, identifying ways to augment disaster response capabilities gains greater significance.

Integration domains

The most common domain was Academic Integration, followed by Event Based Integration, High-Level Government Support, Skills Sustainment, and Geographic Location. Regardless of the method of integration, the focus of most papers with Skills Sustainment and Academic Integration was on training/sustaining skills for military rather than civilian personnel. Examples include the Senior Visiting Surgeon program where experienced vascular surgeons assisted military colleagues early in the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan49,50,62. Though not highlighted by these results, the relationship between military and civilian sectors can and should be bidirectional. This is evident in the influence of military research and battlefield experience on civilian trauma practices, such as the use of balanced resuscitation with blood products, balloon occlusion of the aorta, and early prehospital tourniquet application95–98. Having military providers with adequate and well-maintained trauma skills and knowledge is critical for a ready medical force, which likely motivated research to focus on the applications for military personnel. One reason cited by many papers reflected an aspect of the Military Health System (MHS), in which only one hospital is an American College of Surgeons-verified Level 1 trauma center and the remainder see low volumes of trauma12,13,20,32,37,40,51–53,60,68,70,71,74,77,78. Accordingly, military providers must spend time at civilian hospitals to gain substantive trauma exposure during peacetime. This applied to providers of varying scopes of practice and demonstrated a recognition of the need to train an entire team to deliver appropriate trauma care.

Geographic Location, Event Based Integration, and High-Level Government Support were seen across all methods of integration. Geographic Location involved utilizing proximity of resources for partnerships. There were many examples of medevac resources being used for aeromedical evacuation and patient transport21,29,30,34,38,39,85,88,90. It stands to reason that sharing resources would take advantage of proximity; this also conforms with a Golden Hour mentality and regional trauma coverage. Event Based Integration coincided with disaster and conflict response. Rather than driving integration, these studies highlighted benefits of the comprehensive, integrated trauma system developed in Israel that were apparent when tested by mass casualty incidents, which allowed for quick determination and disposition of critically injured patients from point of injury.

High-Level Government Support was defined as government bodies at the state/provincial level or higher that fostered integration. Established legal mandates provide authority and can create requirements to integrate. Having higher level support can also help overcome regulatory and bureaucratic obstacles while enhancing the sustainability of successful programs. In cases where appropriate credentialing was a challenge, support from government agencies was able to facilitate or create expedited pathways32,42,60,82. This support also took form when specific senior leaders directly fostered new partnerships65,80,83. This domain was especially important for successful communication and logistical coordination59,60,65,79,84,87.

Barriers and facilitators

The administrative indicator was cited most among barriers and facilitators (Table 3). Absence of high-level command coordination across organizations can be an obstacle while strong and supportive leadership is an advantage. Administrative support facilitates essential communication and helps define specific mission parameters, whilst likely leading to more expedient mobilization of resources. When dealing with high-level government entities, the political environment unique to the time and country must be considered. Development of sustainable integration requires ongoing support, which can be subject to different priority-setting between political bodies, especially where funding is concerned. Additionally, support from agencies responsible for medicolegal functions is important for ensuring appropriate credentialing and liability coverage. Streamlining pathways for meeting these needs can circumvent potential legal obstacles.

When bringing together civilian and military entities, it is also important to recognize potential differences in organizational culture and systems of operation. Militaries tend to follow stricter hierarchy than civilian organizations. Understanding this is important for the personnel involved. Differences in equipment and training standards must also be considered, such as with military prehospital providers who have expanded scopes of practice compared to civilian counterparts, given the specific needs of the battlefield environment32.

Knowledge gaps

These studies represent mainly snapshots of their described trauma systems. Some focused on specific aspects of trauma care delivery within the confines of an event or focused on components related to training and readiness. As such, there was little discussion of a country’s trauma system in its entirety. Therefore, all examples of integration are likely not captured in this review.

A notable finding was that most literature came from HICs, with 91.9% of the included studies produced solely by authors from HIC institutions and 75.7% documenting experiences within HICs. Of the six studies with authors from LMICs, three included co-authors from HICs and all were related to disaster/conflict events. Whether this HIC predominance in the literature is related to a lack of integration in LMICs is unclear. Other reasons that may explain this include systemic barriers to LMIC researchers publishing in peer-reviewed indexed journals99, sensitivities in describing military operations, and a relative paucity of comprehensive trauma systems in LMICs. To successfully construct a framework for military-civilian integration that is globally applicable, perspectives of LMICs must be specifically sought.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. Only English search terms were used, and the final studies included were full-text studies in English. Another potential limitation was the ability to capture all reporting of integration. While gray literature was included, there may be more examples of integration that exist in news media and press releases not captured in an academic database search. Similarly, internal or classified government reports on partnerships are not available for review. Additionally, the available literature may suffer from a form of publication bias through which reports of successful integration are more likely to be published. As shown in Figure 2, most countries in the world were not represented by the studies identified for this review. Due to these limitations, the findings cannot be deemed generalizable to the wider global community of military and civilian trauma systems. An additional limitation of this work is that terminology related to integration may change as it is relatively novel work and may update as more research is done. It is likely that this language will evolve as further analysis is conducted.

Conclusion

Integration is a potential avenue for increasing trauma care delivery and maintaining readiness to treat patients injured by combat. This scoping review identified evidence of military and civilian trauma systems integration, from one-time coordination to full systems integration. Domains of integration included Skills Sustainment, Academic Integration, Geographic Location, Event Based Integration, and High-Level Government Support. Available literature largely originated from HICs. Though those examples may potentially serve as guides for integration in the LMIC settings, identifying context-specific examples will allow for a more comprehensive evaluation. Further research is needed to collect this critical data. This information, along with additional cross-sectional analyses from a large and diverse cohort of countries, will provide an initial foundation for the development of a globally applicable integration framework.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent

Not applicable.

Sources of funding

Not applicable.

Author contribution

M.D.B.: abstract review, full text review, data analysis, writing, and study design; E.S.M.: abstract review, full text review, data analysis, and writing; M.A.: abstract review, full text review, and writing/editing; G.C.: abstract review, full text review, and study design; S.N.H.K.: data collection, abstract review, and full text review; R.H.: data collection, abstract review, and full text review; M.B.: data collection, abstract review, and full text review; T.P.M.: data collection, abstract review, and full text review; E.L.R.: data collection, abstract review, and full text review; Y.G.P.: data collection, abstract review, and full text review; E.K.: data collection, abstract review, and full text review; P.A.B.: data collection, review, study accumulation, and methods; G.A.: study design and writing/editing; T.W.: abstract review, full text review, writing/editing, and study design; A.R.: abstract review, full text review, writing/editing, and study design; M.J.: abstract review, full text review, writing/editing, and study design. Group Authors/Contributors - ‘IMPACT Scoping Review Group’ T.B., R.M.K.D.G., C.H., C.J., P.J., T.K., R.L., C.S., H.S., S.W., and N.Y.: initial abstract screening.

Conflicts of interest disclosure

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Research registration unique identifying number (UIN)

Not applicable.

Guarantor

Michael Baird, Emad Madha, Amila Ratnayake, Tamara Worlton, and Michelle Joseph.

Data availability statement

The data was derived from articles published in the literature which are publicly available (on a per journal basis).

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

Presentation

Society of Military Surgeons 10th Annual Military Surgical Symposium, SAGES 2023 Annual Meeting – Montreal, QC, Canada, March 29th, 2023.

In 22nd European Congress of Trauma and Emergency Surgery, ESTES – Ljublajana, Slovenia, May 7th, 2023.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Assistance with Study: IMPACT Scoping Review Group

Tahler Bandarra, MD, Department of General Surgery, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, MD, USA; Rathnayaka M.K.D. Gunasingha, MD, Department of General Surgery, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, MD, USA; Clara Hua, MD, Department of General Surgery, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL, USA; Peter Joo, MD, MPH, Department of Orthopaedics and Rehabilitation, Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA; Carolyn Judge, MD, Navy Medical Research Command, Silver Spring, MD, USA; Tess Komarek, MD, Department of General Surgery, Brooke Army Medical Center, San Antonio, TX, USA; Robert Laverty, MD, Department of General Surgery, Brooke Army Medical Center, San Antonio, TX, USA; Sarah Walsh, PhD, School of Medicine, Uniformed Services University, Bethesda, MD, USA; Carlie Skellington, MPH, School of Medicine, Uniformed Services University, Bethesda, MD, USA; Hannah Szapary, MS, Harvard Medical School, Harvard University, Boston, MA, USA; Nava Yarahmadi, MBBS, MA, Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK

Footnotes

Sponsorships or competing interests that may be relevant to content are disclosed at the end of this article.

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article. Direct URL citations are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal's website, www.lww.com/international-journal-of-surgery.

Published online 18 March 2024

Contributor Information

Michael D. Baird, Email: mdb280@gmail.com.

Emad S. Madha, Email: echomike9102@gmail.com.

Matthew Arnaouti, Email: matthew_arnaouti@hms.harvard.edu.

Gabrielle L. Cahill, Email: gaby.cahill@gmail.com.

Sadeesh N. Hewa Kodikarage, Email: sadeesh.niroshan@gmail.com.

Rachel E. Harris, Email: rachel.harris@usuhs.edu.

Timothy P. Murphy, Email: tim.p.murphy14@gmail.com.

Megan C. Bartel, Email: megan.c.bartel@gmail.com.

Elizabeth L. Rich, Email: elizabethrich91@gmail.com.

Yasar G. Pathirana, Email: yasserpathirana@gmail.com.

Eungjae Kim, Email: njkim2015@gmail.com.

Paul A. Bain, Email: paul_bain@hms.harvard.edu.

Ghassan T. Alswaiti, Email: alsweaiti@gmail.com.

Amila S. Ratnayake, Email: amila.rat@gmail.com.

Tamara J. Worlton, Email: tamara.worlton@usuhs.edu.

Michelle N. Joseph, Email: michelle_joseph@hms.harvard.edu.

Collaborators: Tahler Bandarra, Rathnayaka M.K.D. Gunasingha, Clara Hua, Peter Joo, Carolyn Judge, Tess Komarek, Robert Laverty, Sarah Walsh, Carlie Skellington, Hannah Szapary, and Nava Yarahmadi

References

- 1.WHO . Injuries and violence: World Health Organization; 2021. Accessed March 24, 2023. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/injuries-and-violence#:~:text=Impact%3A,as%20poverty%2C%20crime%20and%20violence

- 2.WHO. Global Health Estimates 2020: Disease burden by Cause, Age, Sex, by Country and by Region, 2000–2019. World Health Organization; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO . Injuries and violence: the facts 2014. World Health Organization; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sakran JV, Greer SE, Werlin E, et al. Care of the injured worldwide: trauma still the neglected disease of modern society. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2012;20:64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gosselin RA, Spiegel DA, Coughlin R, et al. Injuries: the neglected burden in developing countries. Bull World Health Organ 2009;87:246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dijkink S, Nederpelt CJ, Krijnen P, et al. Trauma systems around the world: a systematic overview. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2017;83:917–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mock C, Joshipura M, Arreola-Risa C, et al. An estimate of the number of lives that could be saved through improvements in trauma care globally. World J Surg 2012;36:959–963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mullins RJ, Mann NC. Population-based research assessing the effectiveness of trauma systems. J Trauma 1999;47(3 Suppl):S59–S66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peleg K, Aharonson-Daniel L, Stein M, et al. Increased survival among severe trauma patients: the impact of a national trauma system. Arch Surg 2004;139:1231–1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Razzak JA, Bhatti J, Wright K, et al. Improvement in trauma care for road traffic injuries: an assessment of the effect on mortality in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet 2022;400:329–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nations with Armed Forces/Military Medical Services 2023. Accessed September 12, 2023. https://military-medicine.com/almanac/countries/index.html

- 12.National Academies of Sciences E, and Medicine . A National Trauma Care System: Integrating Military and Civilian Trauma Systems to Achieve Zero Preventable Deaths After Injury. The National Academies Press; 2016:530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jensen G, van Egmond T, Örtenwall P, et al. Military civilian partnerships: international proposals for bridging the Walker Dip. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2020;89:S4–S7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knudson MM, Elster EA, Hoyt DB, et al. The Blue Book: Military-Civilian Partnerships for Trauma Training, Sustainment, and Readiness. American College of Surgeons; 2020:32. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sonderman KA, Citron I, Mukhopadhyay S, et al. Framework for developing a national surgical, obstetric and anaesthesia plan. BJS Open 2019;3:722–732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alswaiti GT, Worlton TJ, Arnaouti M, et al. Military and civilian trauma system integration: a global case series. J Surg Res 2022;283:666–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peters MD, Godfrey C, McInemey P, et al. Scoping Reviews (2020 version) In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI; 2020. p. 406-51. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018;169:467–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ratnayake AS, Joseph MN, Worlton TJ. Framework for analysing and fostering civilian-military medical relations. BMJ Mil Health 2023;169:101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anderson JE, David EA, Loge HB, et al. A model for military-civilian collaboration in academic surgery beyond trauma care. JAMA Surgery 2017;152:891–893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Assa A, Landau DA, Barenboim E, et al. Role of air-medical evacuation in mass-casualty incidents-a train collision experience. Prehosp Disaster Med 2009;24:271–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bein T, Zonies D, Philipp A, et al. Transportable extracorporeal lung support for rescue of severe respiratory failure in combat casualties. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2012;73:1450–1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Benov A, Shkolnik I, Glassberg E, et al. Prehospital trauma experience of the Israel defense forces on the Syrian border 2013–2017. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2019;87:S165–S171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Biswas A, Rahman A, Mashreky SR, et al. Rescue and emergency management of a man-made disaster: lesson learnt from a collapse factory building, Bangladesh. ScientificWorldJournal 2015;2015:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Born CT, Cullison TR, Dean JA, et al. Partnered disaster preparedness: lessons learned from international events. J Am Academy Orthop Surg 2011;19:S44–S48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brophy JR. Shoulder to shoulder: joint military-civilian training benefits both sectors. Homeland First Response 2005;3:18–21. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bush RL, Fairman RM, Flaherty SF, et al. The role of SVS volunteer vascular surgeons in the care of combat casualties: results from Landstuhl, Germany. J Vasc Surg 2009;49:226–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cannon JW, Gross KR, Rasmussen TE. Combating the peacetime effect in military medicine. JAMA Surg 2021;156:5–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Christensen RE, Ottosen CI, Sonne A, et al. Search and rescue helicopters for emergency medical service assistance: a retrospective study. Air Med J 2021;40:269–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cummons CL, Bonham RT, French BP. MAST: an integral part of Hawaii state emergency medical services. Hawaii Med J 1989;48:421–422; 5-6, 9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.D’Amore AR, Hardin CK. Air Force expeditionary medical support unit at the Houston floods: use of a military model in civilian disaster response. Mil Med 2005;170:103–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Derr RE, Roepke DL, Lyons WH. Community hospitals and military sustainment training. J Trauma Nurs 2008;15:200–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fitzsimons MG, Sparks JW, Jones SF, et al. Anesthesia services during Operation Unified Assistance, aboard the USNS mercy, after the tsunami in Southeast Asia. Mil Med 2007;172:227–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gerhardt RT, Stewart T, De Lorenzo RA, et al. Army air ambulance operations in El Paso, Texas: a descriptive study and system review. Prehosp Emerg Care 2000;4:136–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ghanjal A, Bahadori M, Ravangard R. An overview of the health services provision in the 2017 Kermanshah Earthquake. Disaster Med Public Health Prep 2019;13:691–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grant WD, Secreti L. Joint civilian/national guard mass casualty exercise provides model for preparedness training. Mil Med 2007;172:806–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grimm J, Johnson K. Saint Louis Center for sustainment of trauma and readiness skills: a collaborative air force-civilian trauma skills training program. J Emerg Nurs 2016;42:104–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guénot P, Leigh-Smith S, Granger-Veyron N, et al. The involvement of the French military medical service in helicopter rescue missions for Emergency Medical Aid at Sea: the current situation and prospects for the future. J R Nav Med Serv 2019;105:95–102. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guénot P, Coudreuse M, Lely L, et al. Helicopter rescue missions for emergency medical aid at sea: a new assignment for the french military medical service? Air Med J 2021;40:225–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hall MA, Boecker MF, Englert MZ, et al. Objective military trauma team performance improvement from military-civilian partnerships. Am Surg 2018;84:e555–e557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hall MAB, Englert MZ, Hanseman D, et al. Self-efficacy improvement for performance of trauma-related skills due to a military-civilian partnership. Am Surg 2018;84:e505–e507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Henderson DK, Malanoski MP, Corapi G, et al. Bethesda hospitals’ emergency preparedness partnership: a model for transinstitutional collaboration of emergency responses. Disaster Med Public Health Prep 2009;3:168–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Heyman SN, Eldad A, Wiener M. Airborne field hospital in disaster area: lessons from Armenia (1988) and Rwanda (1994). Prehosp Disaster Med 1998;13:21–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Howe CA, Ruane BM, Latham SE, et al. Promotion of cadaver-based military trauma education: integration of civilian and military trauma systems. Mil Med 2020;185:e23–e27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jaffe E, Strugo R, Wacht O. Operation protective edge - a unique challenge for a civilian EMS agency. Prehosp Disaster Med 2015;30:539–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jefferys S, Martin-Bates AJ, Harold A, et al. Epidemiological study of emergency ambulance activation in the British Eastern Sovereign Base Area of Cyprus, September 2013 to August 2016. J R Army Med Corps 2019;165:159–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Johnson AE, Gerlinger TL, Born CT. The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons/Society of Military Orthopaedic Surgeons/Orthopaedic Trauma Associations/Pediatric Orthopaedic Association Disaster Response and Preparedness Course. J Orthop Trauma 2015;29:S23–S25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kashuk JL, Peleg K, Glassberg E, et al. Potential benefits of an integrated military/civilian trauma system: experiences from two major regional conflicts. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2017;25:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Knudson MM, Rasmussen TE. The senior visiting surgeons program: a model for sustained military-civilian collaboration in times of war and peace. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2012;73:S536–S542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Knudson MM, Evans TW, Fang R, et al. A concluding after-action report of the Senior Visiting Surgeon program with the United States Military at Landstuhl Regional Medical Center, Germany. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2014;76:878–883; discussion 83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Knudson MM, Elster EA, Bailey JA, et al. Military–civilian partnerships in training, sustaining, recruitment, retention, and readiness: proceedings from an exploratory first-steps meeting. J Am Coll Surg 2018;227:284–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Knudson MM. A Perfect Storm: 2019 scudder oration on trauma. J Am Coll Surg 2020;230:269–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Knuth TE, Wilson A, Oswald SG. Military training at civilian trauma centers: the first year’s experience with the Regional Trauma Network. Mil Med 1998;163:608–614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lavon O, Hershko D, Barenboim E. Large-scale air-medical transport from a peripheral hospital to level-1 trauma centers after remote mass-casualty incidents in Israel. Prehosp Disaster Med 2009;24:549–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li XH, Zheng JC. Efficient post-disaster patient transportation and transfer: experiences and lessons learned in emergency medical rescue in Aceh after the 2004 Asian tsunami. Mil Med 2014;179:913–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mackenzie C, Donohue J, Wasylina P, et al. How will military/civilian coordination work for reception of mass casualties from overseas? Prehosp Disaster Med 2009;24:380–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Marres G, Bemelman M, van der Eijk J, et al. Major incident hospital: development of a permanent facility for management of incident casualties. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 2009;35:203–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McBroom RJ. Collaborative training with ambulance service NHS trusts. J R Army Med Corps 2008;154:149–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McCartney SF. Combined Support Force 536: Operation Unified Assistance. Mil Med 2006;171:24–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McNamara KJ, Schulman C, Jepsen D, et al. Establishing a collaborative trauma training program with a community trauma center for military nurses. Int J Trauma Nurs 2001;7:49–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.(METRC) TMETRC . Building a Clinical Research Network in Trauma Orthopaedics: The Major Extremity Trauma Research Consortium (METRC). J Orthop Trauma 2016;30:353–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Moore EE, Knudson MM, Schwab CW, et al. Military-civilian collaboration in trauma care and the senior visiting surgeon program. N Engl J Med 2007;357:2723–2727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Morrow RC, Llewellyn DM. Tsunami overview. Mil Med 2006;171:5–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Paunksnis A, Barzdziukas V, Kurapkiene S, et al. An assessment of telemedicine possibilities in massive casualties situations. Rocz Akad Med Bialymst 2005;50:201–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Peake JB. The Project HOPE and USNS Mercy tsunami “experiment”. Mil Med 2006;171:27–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pohlmann GP, Reynolds NC, Zimmerman RC. Training military reserve medics in combat casualty care: an example of military-civilian collaboration. Mil Med 1986;151:97–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Potter SJ, Carter GE. The Omagh bombing–a medical perspective. J R Army Med Corps 2000;146:18–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Saldanha V, Yi F, Lewis JD, et al. Staying at the cutting edge: partnership with a level 1 trauma center improves clinical currency and wartime readiness for military surgeons. Mil Med 2016;181:459–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Samuel N, Epstein D, Oren A, et al. Severe pediatric war trauma: a military-civilian collaboration from retrieval to repatriation. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2021;90:e1–e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schmied Blackman V, Torres T, Stakley JA, et al. Quantifying clinical opportunities at the navy trauma training center. Mil Med 2021;186:40–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schreiber MA, Holcomb JB, Conaway CW, et al. Military trauma training performed in a civilian trauma center. J Surg Res 2002;104:8–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schulman CI, Graygo J, Wilson K, et al. Training forward surgical teams: do military-civilian collaborations work? The United States Army Medical Department Journal. 2010;October - December:17-21. [PubMed]

- 73.Schwartz D, Resheff A, Geftler A, et al. Aero-medical evacuation from the second Israel-Lebanon war: a descriptive study. Mil Med 2009;174:551–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Shin DH, Hooten KG, Sindelar BD, et al. Direct enhancement of readiness for wartime critical specialties by civilian-military partnerships for neurosurgical care: residency training and beyond. Neurosurg Focus 2018;45:E17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Smith BD. Advances in military medic training. How civilian paramedics helped upgrade training for U.S Army flight medics. EMS World 2015;44:46–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Smith JE, Withnall RD, Rickard RF, et al. A pilot study to evaluate the utility of live training (LIVEX) in the operational preparedness of UK military trauma teams. Postgrad Med J 2016;92:697–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Stewart TS. Smart training: the US Army’s pilot project for combat trauma surgical training. Seminars in Perioperative. Nursing 2000;9:11–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Stinner DJ, Johnson AE, Pollak A, et al. Zero Preventable Deaths and Minimizing Disability”-The Challenge Set Forth by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. J Orthop Trauma 2017;31:e110–e115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Takada Y, Otomo Y, Karki KB. Evaluation of emergency medical team coordination following the 2015 Nepal earthquake. Disaster Med Public Health Prep 2021;15:308–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tarantino D. Asian Tsunami relief: Department of Defense public health response: policy and strategic coordination considerations. Mil Med 2006;171:15–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Thomas S. Making a difference: CRNAs aboard the USNS Comfort respond to the disaster in Haiti. AANA J 2010;78:264–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Thorson CM, Dubose JJ, Rhee P, et al. Military trauma training at civilian centers: a decade of advancements. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2012;73:S483–S489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Timboe HL, Holt GR. Project HOPE volunteers and the Navy Hospital Ship Mercy. Mil Med 2006;171:34–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tran MD, Garner AA, Morrison I, et al. The Bali bombing: civilian aeromedical evacuation. Med J Aust 2003;179:353–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tudose DC, Nica D. Air MEDEVAC in case of multiple casualties - The experience of civilian-military cooperation in RoAF. Romanian J Military Med 2016;119:23–26. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tyre TE. Wake-up call: A bioterrorism exercise. Mil Med 2001;166:90–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Walk RM, Donahue TF, Stockinger Z, et al. Haitian earthquake relief: disaster response aboard the USNS comfort. Disaster Med Public Health Prep 2012;6:370–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Williams MJ. A review of medical airlifts by a search and rescue squadron on the east coast of England over 18 years. Arch Emerg Med 1991;8:108–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wong W, Brandt L, Keenan ME. Massachusetts General Hospital participation in Operation Unified Assistance for tsunami relief in Banda Aceh, Indonesia. Mil Med 2006;171:37–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zhang L, Liu Y, Liu X, et al. Rescue efforts management and characteristics of casualties of the Wenchuan earthquake in China. Emerg Med J 2011;28:618–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zic R, Skegro M, Mitar D, et al. Organization and work of the war hospital in Tomislavgrad during the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina from 1992 to 1995. Mil Med 2001;166:59–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Craigie RJ, Farrelly PJ, Santos R, et al. Manchester Arena bombing: lessons learnt from a mass casualty incident. BMJ Military Health 2020;166:72–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Michaud J, Moss K, Licina D, et al. Militaries and global health: peace, conflict, and disaster response. The Lancet 2019;393:276–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.IPCC . Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Cambridge University Press; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bulger EM, Perina DG, Qasim Z, et al. Clinical use of resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA) in civilian trauma systems in the USA, 2019: a joint statement from the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma, the American College of Emergency Physicians, the National Association of Emergency Medical Services Physicians and the National Association of Emergency Medical Technicians. Trauma Surg Acute Care Open 2019;4:e000376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.France K, Handford C. Impact of military medicine on civilian medical practice in the UK from 2009 to 2020. BMJ Mil Health 2021;167:275–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Holcomb JB, del Junco DJ, Fox EE, et al. The Prospective, Observational, Multicenter, Major Trauma Transfusion (PROMMTT) study: comparative effectiveness of a time-varying treatment with competing risks. JAMA Surg 2013;148:127–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hughes CW. Use of an intra-aortic balloon catheter tamponade for controlling intra-abdominal hemorrhage in man. Surgery 1954;36:65–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Busse CE, Anderson EW, Endale T, et al. Strengthening research capacity: a systematic review of manuscript writing and publishing interventions for researchers in low-income and middle-income countries. BMJ Glob Health 2022;7:e008059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data was derived from articles published in the literature which are publicly available (on a per journal basis).