The patient should be the primary manager of chronic disease, guided and coached by a doctor or other practitioner to devise the best therapeutic regimen.1 The practitioner and patient should work as partners,2 developing strategies that give the patient the best chance to control his or her own disease and reduce the physical, psychological, social, and economic consequences of chronic illness.

In this article we consider the quality of education for patients and practitioners who are trying to manage chronic disease. We argue that neither patients nor practitioners are taught the skills that will most enable each to carry out his or her role and responsibility for disease management. We use asthma, a chronic lung disease, to show how patients and practitioners are being taught the wrong things.

Summary points

Disease control, especially asthma, depends on the quality of partnership between patient and physician

Most current patient education activities are not adequately based on evaluated models of effective disease management

One such model, self regulation, has been shown to change patients' behaviour and improve their health status

Specific techniques can help doctors to develop partnerships with patients

Including these techniques in doctors' education can lead to reduced use of and higher satisfaction with health care by patients with asthma

Methods

We searched Medline and used previously published reviews to find articles on managing asthma. We did not formally assess the methodological quality of individual studies.

Asthma: the knowledge gap

In recent decades there have been striking advances in the clinical treatment of asthma,2 yet morbidity and mortality for the disease are at an all time high.3 This gap between the scientific evidence and the continuing negative effect of asthma on society depends to a considerable extent on patients' behaviour and practitioners' performance.4 To understand what patients and clinicians must be taught to achieve disease control, we have to look first at the goals of treatment.

The goals of asthma treatment

The aim of treatment of asthma is to control symptoms, restore full physical and psychosocial functioning, and eliminate interference with social relationships and quality of life.2 To reach these goals, people with asthma (including children and their parents) must at least be able to use prescribed drugs in the proper manner to prevent or control symptoms, identify and avoid the things that cause symptoms, develop or maintain family and other necessary social support, and communicate effectively with healthcare providers. Complicating this process is the fact that, apart from some very basic management strategies that are important for almost all people with asthma, the tasks of management are largely unique to each person. These tasks depend on individual disease characteristics, personal attributes, and aspects of lifestyle considerations, and on the way these change over time. Because asthma management is dynamic, people must develop their own repertoires of effective behavioural strategies and use a decision making process that allows them to change or refine strategies as needed.5 Furthermore, it is impossible for clinicians to provide direction for every contingency a patient may face, so individuals must exercise a high degree of independent decision making about asthma within their doctor's general guidelines.

These goals clearly reflect the need for full involvement of practitioner and patient in a partnership, a concept discussed extensively in the literature about disease management.6 But the dismal epidemiology of asthma suggests that neither partner is sufficiently effective in controlling the disease, and we think that inadequate preparation for this management role is an important factor in this.

Preparing the patient for effective disease management

The failure to adequately prepare patients for chronic disease management has two components: firstly, the failure to adopt and adapt existing education programmes of proved value7,8 and, secondly, the failure to see management by patients as a behavioural process based largely on an individual's ability to self regulate.9,10

Education programmes

Education for patients with asthma has become a routine part of many medical services. But most education provided, whether informal within consultations or formally organised into scheduled classes for groups of patients, is based on an ad hoc set of messages and skills that professionals believe patients need to acquire.11 The relatively poor quality of most formal patient education on asthma, usually comprising didactic lectures from clinicians,11 is surprising.

Since the mid-1980s several models of asthma education for children and adults, well designed and based on behavioural theory, have been evaluated and shown to achieve the desired outcomes, such as reduced use of health services and better quality of life. (Tables A and B on the BMJ's website give details such model programmes.) These programmes are diverse and vary in format, teaching methods, and materials used. Each, however, is formulated from a theoretical understanding of human behaviour and motivation and recognises what predisposes patients to manage disease.

Self regulation

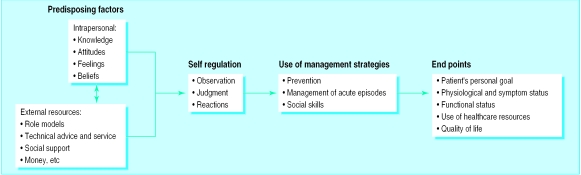

Theories of human behaviour based on accepted principles of learning and motivation can help us achieve the goal of optimum disease management. As an example, the figure shows a behavioural model based on three ideas.12 The first idea is that several factors predispose or enable one to manage a disease. Secondly, management by the patient involves the conscious use of strategies to manipulate situations and thereby reduce the impact of disease on daily life. The patient learns what strategies work (or do not) through processes of self regulation. Thirdly, management is not an end in itself but is the means to other ends.

Self regulation is the process of observing, making judgments, and reacting realistically and appropriately to one's own efforts to manage a task. It is a means by which patients determine what they will do, given their specific goals, social context, and their perceptions of their own capability. For example, a young man with asthma who wants to play basketball thinks drugs will help and so uses them preventively, takes a reliever drug when exercising strenuously, seeks moral support from his friends and coaches, and uses other strategies that enable him to reach his personal goal. He learns which strategies are effective through self regulation.

Self regulation may be particularly important in diseases like asthma for which there is no proved formula for optimum management and patients and their families must exercise a high degree of decision making, usually in the absence of health professionals. Patients have to recognise when their disease impedes reaching their goals, judge what they might do to improve the situation, test management strategies by trying new behaviour; and draw conclusions. Patients also have to develop the confidence to carry out effective behaviour—that is, develop self efficacy.9

Thus effective patient education should not be a matter of simply providing information about the disease but should allow patients to develop the capacity to observe themselves, make sensible judgments, feel confident, and recognise desirable outcomes.13–16 There is little correlation between general knowledge about asthma and health outcomes.17 Similarly, the link between general attitudes and specific health behaviours is weak.18 Feeling able to carry out a management task makes people more likely to try the task,13,19 but confidence alone does not ensure suitable behaviour.

Defining success

What is the goal of patient education in asthma and what signals that the goal has been reached? Practitioners and patients bring different expertise to asthma control (technical versus experiential) and focus on different outcomes. The practitioner will often be concerned with the results of objective measures, such as pulmonary function tests, and the need for drugs. Patients focus more readily on their quality of life, such as the degree of disruption of normal activities. Measures assessing clinical outcome, functional health status, and quality of life do not always correlate well with each other.20 A patient is much more likely to be motivated to follow a practitioner's recommendations when the goal of management reflects the patient's own interests and concerns.

Preparing the practitioner for effective partnership with patients

While the general state of patient education in asthma falls far short of the standard set by evaluated models, the state of clinical education is even less robust. A review of postgraduate courses on asthma for doctors that are sponsored by professional associations, medical care facilities, pharmaceutical companies, and other providers, shows that they focus almost solely on therapeutic recommendations to doctors. The predominant topics are the correct choice and administration of drugs, the basic mechanisms of disease, the use of spirometry, and use of monitoring devices for patients (such as peak flow meters and symptom diaries). Furthermore, despite the wide availability of clinical education on asthma, research shows that in the United States doctors are not prescribing adequately21–23 and that their patients are not following medical recommendations.1,24

Only a few empirical studies have examined the effect of education for practising doctors on the health of their patients25–27 or on patients' views about practitioners' performance.28,29

Communication and teaching skills for doctors

Many barriers to effective communication have been identified in studies of the doctor-patient relationship. Patients often feel that they are wasting the doctor's valuable time, omit details they deem unimportant, are embarrassed to mention things they think will place them in an unfavourable light, do not understand medical terms, and may believe the doctor has not really listened and therefore does not have the information needed to make a good treatment decision.30 The box shows 10 proved techniques for improving communication and patient education.31

Communication techniques derived from studies of the doctor-patient relationship

1 Attend to the patient (signalled by cues such as making eye contact, sitting rather than standing when conversing with the patient, moving closer to the patient, and leaning slightly forward to attend to the discussion)

2 Elicit the patient's underlying concerns about the condition

3 Construct reassuring messages that alleviate fears (reducing fear as a distraction enables the patient to focus on what you are saying)

4 Address any immediate concerns that the family expresses (enabling patients to refocus their attention toward the information being provided)

5 Engage the patient in interactive conversation through use of open ended questions, simple language, and analogies to teach important concepts (dialogue that is interactive produces richer information)

6 Tailor the treatment regimen by eliciting and addressing potential problems in the timing, dose, or side effects of the drugs recommended

7 Use appropriate non-verbal encouragement (such as a pat on the shoulder, nodding in agreement) and verbal praise when the patient reports using correct disease management strategies

8 Elicit the patient's immediate objective related to controlling the disease and reach agreement with the family on a short term goal (that is, a short term objective both provider and patient will strive to reach that is important to the patient)

9 Review the long term plan for the patient's treatment so the patient knows what to expect over time, knows the situations under which the physician will modify treatment, and knows the criteria for judging the success of the treatment plan

10 Help the patient plan in advance for decision making about the chronic condition (such as using diary information or guidelines for handling potential problems and exploring contingencies in managing the disease)

A large randomised controlled trial tested the inclusion of these communication principles in the education of paediatricians, evaluating the effects of this training on the doctors' behaviour and on the health status of their patients with asthma.31,32 The intervention was an interactive seminar comprising brief lectures from specialists, a videotape showing effective use of the 10 communication techniques, case studies presenting troublesome clinical problems, a protocol by which doctors could assess their own behaviour regarding communication with patients, and a review of messages to communicate and materials to use when teaching patients. The clinical content of the seminar was based on the guidelines of the US National Asthma Education Program Expert Panel.2 At follow up about two years later, the doctors in the intervention group were more likely than those in the control group to write down for patients how to adjust drugs according to symptoms experienced and to provide guidelines for patients on how to adjust treatment when clinical conditions changed.32 Children seen by the doctors in the intervention group had fewer hospital admissions than the controls' patients, and their parents communicated more effectively with the doctors. Yet these doctors spent no more time with their asthma patients than did the control doctors, and appropriate clinical treatment alone did not improve patients' health status.

Conclusions

Neither patients nor practitioners are being taught the right things about managing asthma. Relying on intuition, convenience, and habit (apparently the basis of most current education on asthma) will not do enough to enable patients and practitioners to control chronic disease. Effective teaching on chronic disease must be based more closely on the findings of behavioural research.

Supplementary Material

Figure.

Model of patient management of chronic lung disease (adapted with permission from Clark and Starr 199412)

Footnotes

Funding: The work presented here was supported by grant HL-44976, “MD/Family Partnership: Education in Asthma Management,” from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Competing interests: None declared.

website extra: Two tables listing studies of asthma patient education appear on the BMJ's website www.bmj.com

References

- 1.Mellins RB, Evans D, Clark N, Zimmerman B, Wiessemann S. Developing and communicating a long-term treatment plan for asthma in the primary care setting. Am Fam Physician (in press). [PubMed]

- 2.Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma. National Asthma Education Program expert panel report. Bethesda, MD: National Asthma Education Program, Office of Prevention, Education and Control, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; 1997. . (NIH Publication 97-3042.) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weiss KB, Gergen PJ, Wagener DK. Breathing better or worse? The changing epidemiology of asthma morbidity and mortality. Annu Rev Public Health. 1993;14:491–513. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pu.14.050193.002423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Global Initiative on Asthma. A practical guide for public health officials and health care professionals based on the global strategy for asthma management and prevention. NHLBI/WHO workshop report. Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Health; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilson-Pessano S, Mellins RB. Summary of workshop discussion. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1987;80:487. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cherniak NS, Altose MD, Homma I, editors. Rehabilitation of the patient with respiratory disease. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clark NM, Nothwehr FK. Self-management of asthma by adult patients. Patient Educ Counselling. 1997;32(1):S5–20. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(97)00092-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gibson PG, Coughlan J, Abramson M. Self-management education for adults with asthma improves health outcomes. West J Med. 1999;170:266. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: a social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clark N, Zimmerman BJ. A social cognitive view of self-regulated learning about health. Health Educ Res. 1990;5:371–379. doi: 10.1177/1090198114547512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Asthma certification project consensus conference. Washington DC: American Lung Association; 1999. pp. 24–25. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clark NM, Starr NS. Management of asthma by patients and families. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;149:S54–S66. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/149.2_Pt_2.S54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clark N, Rosenstock I, Hassan H, Wasilewski Y, Evans D, Feldman C, et al. The effect of health beliefs and feelings of self-efficacy on self-management behavior of children with a chronic disease. Patient Counseling Educ. 1988;11(2):131–139. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clark NM, Janz NK, Dodge JA, Sharpe PA. Self-regulation in health behavior: The “take PRIDE” program. Health Educ Q. 1992;19:341–354. doi: 10.1177/109019819201900306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clark NM, Evans D, Zimmerman BJ, Levison MJ, Mellins RB. Patient and family management of asthma: theory-based techniques for the clinician. J Asthma. 1994;3:427–435. doi: 10.3109/02770909409089484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clark NM, Dodge JA. Exploring self-efficacy as a predictor of disease management. Health Educ Behav. 1999;26:72–89. doi: 10.1177/109019819902600107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takakura S, Hasegawa T, Ishihara K, Fujji H, Nishimura T, Okazaki M, et al. World Asthma Meeting, Barcelona, Spain, 1998. Abstracts. New York: American Thoracic Society, European Respiratory Society; 1998. Assessment of patients' understanding of their asthmatic condition established in an outpatient clinic. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Becker MH. Patient adherence to prescribed therapies. Med Care. 1985;23:539–555. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198505000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O'Leary A. Self-efficacy and health. Behav Res Ther. 1985;23:437–451. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(85)90172-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Juniper EF, Guyatt GH, Epstein RS, Ferrie PJ, Jaeschke R, Hiller TK. Evaluation of impairment of health related quality of life in asthma: Development of a questionnaire for use in clinical trials. Respir Med. 1991;85:76–83. doi: 10.1136/thx.47.2.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crain EF, Weiss KB, Fagan MJ. Pediatric asthma care in US emergency departments: current practice in the context of the National Institutes of Health Guidelines. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1995;149:898–901. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1995.02170210067012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goodman DC, Lozano P, Stukel TA, Chang C, Hecht J. Has asthma medication use in children become more frequent, more appropriate, or both? Pediatrics. 1999;104:187–194. doi: 10.1542/peds.104.2.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lomas J, Anderson GM, Domnick-Pierre K, Vayda E, Inking MW, Hannah WJ. Do practice guidelines guide practice? The effect of a consensus statement on the practice of physicians. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:1306–1311. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198911093211906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rand CS, Wise RA, Nides M, Simmons MS, Bleecker ER, Kusek JW, et al. Metered-dose inhaler adherence in a clinical trial. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;146:1559–1564. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/146.6.1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davis DA, Thomson MA, Oxman AD, Haynes RB. Evidence for the effectiveness of CME. JAMA. 1992;268:1111–1117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Inui TS, Yourtee EL, Williamson JW. Improving outcomes in hypertension after physician tutorials. Ann Intern Med. 1976;84:646–651. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-84-6-646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maiman LA, Becker MH, Kiptak GS, Nazarian LF, Rounds KA. Improving pediatricians' compliance-enhancing practices: a randomized trial. Am J Dis Child. 1988;142:733–779. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1988.02150070087033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roter DL, Hall JA, Kern DE, Barker LR, Cole KA, Roca RP. Improving physicians' interviewing skills and reducing patients' emotional distress: a randomized clinical trial. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:1877–1884. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roter DL, Stewart M, Putnam S, Lipkin M, Stiles W, Inui T. Communication patterns of primary care physicians. JAMA. 1997;270:35–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Becker MH. Theoretical models of adherence and strategies for improving adherence. In: Schumaker SA, Schron EG, Ockene JK, editors. Handbook of health behavior change. New York, NY: Springer Publishing; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clark NM, Gong M, Schork A, Evans D, Roloff D, Hurwitz M, et al. Impact of education for physicians on patient outcomes. Pediatrics. 1998;101:831–836. doi: 10.1542/peds.101.5.831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clark NM, Gong M, Schork A, Maiman L, Evans D, Hurwitz M, et al. A scale for assessing health care providers' teaching and communication behavior regarding asthma. Health Educ Behav. 1997;24:245–256. doi: 10.1177/109019819702400211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.