Abstract

Exogenous mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV) is carried from the gut of suckling pups to the mammary glands by lymphocytes and induces mammary gland tumors. MMTV-induced tumor incidence in inbred mice of different strains ranges from 0 to as high as 100%. For example, mice of the C3H/HeN strain are highly susceptible, whereas mice of the I/LnJ strain are highly resistant. Of the different factors that together determine the susceptibility of mice to development of MMTV-induced mammary tumors, genetic elements play a major role, although very few genes that determine a susceptibility-resistance phenotype have been identified so far. Our data indicate that MMTV fails to infect mammary glands in I/LnJ mice foster nursed on viremic C3H/HeN females, even though the I/LnJ mammary tissue is not refractory to MMTV infection. Lymphocytes from fostered I/LnJ mice contained integrated MMTV proviruses and shed virus but failed to establish infection in the mammary glands of susceptible syngeneic (I × C3H.JK)F1 females. Based on the susceptible-resistant phenotype distribution in N2 females, both MMTV mammary gland infection and mammary gland tumor development in I/LnJ mice are controlled by a single locus.

Exogenous mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV) is transmitted from infected female mice to newborns through the milk and causes mammary carcinomas in susceptible animals (36). In addition, all common strains of laboratory mice contain endogenous mouse mammary tumor viruses (Mtv) (16). The majority of endogenous Mtv do not produce infectious viral particles because of mutations in either their transcriptional regulatory or coding regions (16). The long terminal repeat (LTR) of exogenous MMTV and endogenous Mtv encodes a superantigen (SAg) (15). SAgs play an important role in the MMTV life cycle. Cells of the immune system, particularly B cells, are the first targets of this virus (11). The infected B cells present viral SAgs in the context of major histocompatibility (MHC) class II molecules to T cells, leading to the stimulation and consequent proliferation of specific Vβ-bearing T cells and, in turn, proliferation of bystander cells (27). These events result in viral amplification and subsequent virus transport to the mammary glands. SAgs present in the germ line cause deletion of the Vβ+ T-cell subsets during formation of the immune repertoire (2). SAg function is indispensable to the MMTV life cycle, because mice that lack SAg-cognate T cells due to the expression of transgenes (23) or endogenous proviruses (27) cannot be infected with exogenous viruses bearing SAgs of the same Vβ specificity. In addition, viruses without functional SAgs can not propagate in vivo (24).

Once integrated into a chromosome, expression of proviral DNA is regulated by specific sequences within the LTR that cause increased viral transcription in response to glucocorticoid receptor/steroid hormone complexes (43). The increased virion production that occurs during lactation results in a greater number of infected mammary gland cells and more proviral integrations into the genome. MMTV does not encode an oncogene, and mammary tumorigenesis therefore takes place after proviral insertion near specific cellular proto-oncogenes, activating them (37). MMTV-induced mammary adenocarcinomas develop from either hyperplastic alveolar nodules (HANs) or plaques (36). HANs are focal proliferations of lobuloalveolar epithelium. They contain immortal cells that can be propagated as hyperplastic outgrowths by serial transplantation in gland-free mammary fat pads of a syngeneic host (36). Mammary carcinomas are postulated to arise from HANs, hyperplastic outgrowths, and plaques by progressive clonal selection of variants with increased growth autonomy.

The generation of inbred strains of mice has led to our understanding that genetic factors play a role in the induction of different forms of cancer, including mammary gland tumors. Resistance or susceptibility to MMTV infection and subsequent tumorigenesis was mapped, in part, to the MHC locus (33). Class II MHC proteins are polymorphic membrane glycoproteins essential for presenting peptides generated by degradation of endocytosed foreign antigens to CD4+ T cells. In the mouse, there are two isotypic class II heterodimeric proteins, AαAβ (I-A) and EαEβ (I-E), both of which can present processed peptides to T cells. Inbred mice of b, f, q, and s MHC haplotypes do not express I-E molecules due to mutations in either the Eα or Eβ gene (10, 17). Since the I-E product of MHC class II molecules is required for SAg presentation, mice with the I-E-negative MHC class II haplotypes (for instance, C57BL/6) are relatively resistant to MMTV infection and MMTV-induced mammary tumors (42).

Another type of resistance is associated with endogenous Mtv loci. The presence of a particular endogenous Mtv in the genome of a particular mouse strain can be deduced from the absence of T cells expressing T-cell receptors (TCRs) with the Vβ element that interacts with the SAg of that particular Mtv (16, 20). As a result, mice exposed to an exogenous virus that encodes a SAg with the same specificity as the endogenous Mtv are resistant to the virus and do not develop mammary gland tumors (23, 27).

Mice of the I/LnJ strain are resistant to MMTV(C3H)-induced mammary tumors (5, 12). However, F1 females produced from matings between I/LnJ mice and another resistant strain, C57BL/6J, were susceptible to MMTV(C3H) infection and mammary tumor development (7, 8; T. Golovkina et al., unpublished data), suggesting that the mechanism of resistance to mammary tumorigenesis in I/LnJ mice differs from that in C57BL mice and does not rest in the MHC class II locus. Mammary tissue fragments from parental I/LnJ mice, transplanted into mammary parenchyma-free fat pads of MMTV-infected (C57BL/6 × I)F1 hybrids, were susceptible to milk-borne MMTV infection (34, 35). HANs and tumors developed in mammary transplants from I/LnJ donors upon hormonal treatment. Both tumors and HANs contained large numbers of MMTV particles (34, 35). These data suggested that resistance to MMTV-induced mammary tumors in I/LnJ mice is not due to the refractoriness of their mammary gland tissues to MMTV infection.

To determine whether the resistance of I/LnJ strain mice to MMTV-induced mammary tumor development is inherited as a Mendelian trait, crosses between susceptible C3H/He MMTV+ females and resistant I/LnJ males were examined (6). The F1 female mice derived from these crosses were as susceptible as C3H/He MMTV+ mice to MMTV-induced mammary tumor development. Thus, the resistance to MMTV-induced mammary tumors in I/LnJ mice is inherited in a recessive manner.

We have found that resistance to MMTV-induced mammary tumors in I/LnJ mice results from the failure of the virus to infect mammary gland cells. However, the MHC class II H-2-haplotype carried by I/LnJ mice expresses the I-E molecule and can present viral SAg. In addition, I/LnJ mice have a normal percentage of MMTV(C3H) SAg-cognate CD4+ Vβ14+ T cells. Thus, these data suggest that resistance to MMTV(C3H) viral infection and subsequent mammary tumorigenesis in I/LnJ mice does not rest in an inappropriate MHC class II haplotype or in the inheritance of an endogenous Mtv locus with the same MMTV(C3H) SAg specificity. Thus, I/LnJ mice have a novel mechanism of resistance to MMTV infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

All mice used in this study were bred and maintained at the animal facility of The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, Maine. I/LnJ and C3H.JK-H2j H2-T18b/Sn (C3H.JK) mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. C3H/HeN MMTV+ mice were purchased from the National Cancer Institute, Frederick Cancer Research Facility, Frederick, Md.

Antibodies and fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis.

Mononuclear peripheral blood lymphocytes were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate-coupled monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) against the Vβ14 TCR chain (PharMingen, Inc., San Diego, Calif.). Anti-CD4 antibodies (GK 1.5) coupled to phycoerythrin (Life Technologies, Grand Island, N.Y.) were used in the second dimension. Leukocytes were recovered from a heparinized blood sample by centrifugation through a Ficoll-Hypaque cushion. Peripheral blood lymphocytes were analyzed by a FACScan (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, Calif.) flow cytometer and CellQuest software program.

Isolation of B and T cells.

Primary lymphocytes were isolated from the spleens and lymph nodes of MMTV(C3H)-infected C3H/HeN, I/LnJ, and C3H.JK mice. T and B cells were purified from the pooled lymphoid organs of two or three mice. Single-cell suspensions were prepared in phosphate buffered saline solution. Cells were washed and erythrocytes were lysed. T cells were isolated by treatment with MAbs against CD4 (GK1.5, made in rat) and CD8 (TIB 105, made in rat) for 30 min on ice, followed by positive selection with magnetic beads bound to anti-rat immunoglobulin G (IgG) from PerSeptive Biosystems (Framingham, Mass.) according to the manufacturer's protocol. B cells were isolated from the spleens of mice indicated by treatment with MAbs against B220 (TIB 146, made in rat) and MAbs against MHC class II I-E molecule (14.4.S, made in mouse) for 30 min on ice, followed by positive selection with a mixture of magnetic beads bound to anti-mouse IgM, IgG, and anti-rat IgG.

Genomic DNA isolation, PCR, and Southern blot analysis.

High-molecular-weight DNA (0.25 μg) isolated from spleens, thymi, Peyer's patches, and T and B cells was amplified by PCR. Amplification of newly integrated copies of exogenous MMTV(C3H) viruses in infected I/LnJ, C3H.JK, and C3H/HeN mice was accomplished using the following primers: a forward primer specific for the MMTV(C3H) LTR (5′ GACAGTGGCTGGACTAATAGAACATT 3′, nucleotides 897 to 922) and a primer-binding site-specific MMTV BR6 reverse primer (5′ CCTACCTCTTCTCTGTAGGCGAGAC 3′, nucleotides 1613 to 1589) as previously described (24). Semiquantitative PCR was carried out as follows: 28 cycles of 1 min at 49°C, 1 min at 72°C, and 1 min at 94°C gave linear DNA amplification, whereas after 32 cycles, the amplification had plateaued (nonquantitative conditions). After PCR amplification, 1/100 part (semiquantitative conditions) or 1/20 part (nonquantitative conditions) of the original volume was run on a 1.5% agarose gel. Southern blots of the PCR products were hybridized with an LTR-specific probe as previously published (24).

Virus purification and reverse transcription (RT)-PCR analysis.

Primary lymphocytes isolated from spleens of two (see Fig. 2B) or four (Fig. 2B) 4-month-old MMTV-infected I/LnJ and C3H/HeN mice were plated at 4 · 106 cells/ml in Click's medium (Life Technologies) supplemented with 5% fetal calf serum in the presence of 1 μg of lipopolysaccharide (Sigma, Inc., St. Louis, Mo.) per ml. After 48 h of culture, supernatants were filtered through 0.45-μm-pore-size filters, and virus was pelleted by centrifugation at 124,000 × g for 1 h at 4°C. RNA was extracted from the virus pellet by guanidine thiocyanate extraction and CsCl gradient centrifugation (23).

FIG. 2.

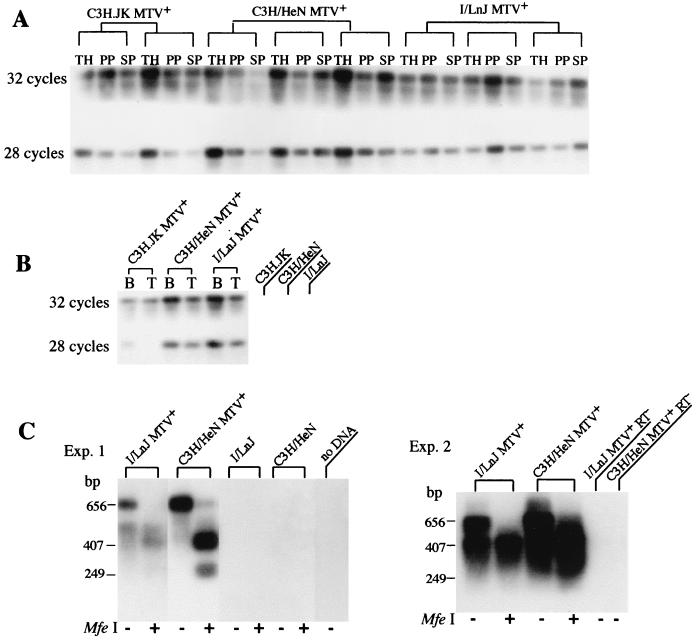

Primary lymphoid cells from neonatally infected I/LnJ mice are productively infected. (A) PCR was carried out with the MMTV(C3H) LTR-gag-specific primers under nonquantitative (32 cycles) or semiquantitative (28 cycles) conditions (24) with 0.25 mg of DNA isolated from thymi (TH), Peyer's patches (PP), and spleens (SP) of I/LnJ, C3H.JK, and C3H/HeN mice nursed on C3H/HeN MMTV+ females. Southern blots of PCR products were hybridized with LTR-specific probe as previously published (24). (B) DNA (0.25 mg) extracted from purified primary B cells (B) and T cells (T) was subjected to PCR analysis under nonquantitative or semiquantitative conditions. C3H.JK, C3H/HeN, and I/LnJ, tail DNA isolated from C3H.JK, C3H/HeN, and I/LnJ mice, respectively. All mice analyzed were 2 months old. (C) Primary lymphocytes isolated from spleens of two (experiment 1) or four (experiment 2) 4-month-old MMTV-infected I/LnJ (I/LnJ MTV+), C3H/HeN (C3H/HeN MTV+), and uninfected I/LnJ (I/LnJ) and C3H/HeN (C3H/HeN) mice were cultured for 48 h. Virus was pelleted from cell supernatants. RNA extracted from the virus pellet was subjected to RT-PCR analysis with MMTV(C3H) LTR-specific primers or followed by digestion with MfeI (previously described (24). After amplification and agarose gel electrophoresis, the products were transferred to nylon membranes and hybridized with a probe specific to the MMTV LTR (24). I/LnJ MTV+RT− and C3H/HeN MTV+RT−, samples in which RT was not included to control for possible DNA contamination. In the second experiments, the 249-bp band is not readily observed due to the brief exposure.

Semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis was accomplished by synthesis of cDNA from RNA isolated from viral particles with MMTV(C3H) LTR-specific primers, followed by digestion with MfeI (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.) as previously described (24). After amplification and agarose gel electrophoresis, the products were transferred to nylon membranes and hybridized with a probe specific to the MMTV LTR (24).

RNase T1 protection assays.

RNase T1 protection assays were performed as previously described (22) with a probe specific for MMTV(C3H) viral transcripts (25). Forty micrograms of total RNA isolated from the lactating mammary glands and 5 μg of RNA isolated from milk were used.

Mammary gland tumorigenesis.

Mammary gland tumor incidence in (C3H/HeN × I/LnJ)F1 MMTV+, N2, and C3H/HeN MMTV+ mice was monitored by weekly palpation of the animals. Tumor-bearing mice were sacrificed, and DNA isolated from a portion of each tumor was subjected to Southern blot analysis as described previously (25, 40). All of the tumors contained new MMTV integrants, indicating that the tumors were caused by the virus (results not shown).

RESULTS

The I/LnJ strain, developed by Strong, was used for mammary tumor studies in the laboratories of Andervont and Nandi, who showed that mammary tumor incidence is very low in breeding females, with or without MMTV infection (6, 7, 34). However, the nature of MMTV infection in I/LnJ mice or even whether these mice were infectable remained unknown, because only mammary tumor incidence was monitored. Therefore, in order to uncover the mechanism of resistance to MMTV-induced tumors, we first determined whether I/LnJ mice are susceptible to MMTV infection.

T-cell deletion in I/LnJ mice fostered by C3H/HeN MMTV+ mice.

Whereas conventional antigens are recognized by T cells as peptide fragments bound to MHC molecules and activate a limited fraction of T cells, SAgs affect relatively large numbers of T cells based on their intrinsic affinity for certain Vβ chains of the TCR (31). Another distinctive feature of SAgs is the requirement for presenting cells that express MHC class II molecules, such as B cells or dendritic cells. I-E molecules are the most efficient presenters for almost all known MMTV SAgs (2, 28). Because MMTV requires SAg function to invade its host, most resistant phenotypes found in different inbred mice were mapped to the MHC locus (18).

I/LnJ mice have the H-2j haplotype. To determine whether MHC class II molecules of this haplotype express the I-E molecule, we tested a panel of hybridomas directed against I-E molecules of different haplotypes. We found that a hybridoma (14.4.S) originally raised against I-Ed MHC class II molecules cross-reacted with I-Ej molecules expressed on I/LnJ spleen cells (data not shown). Therefore, H-2j MHC class II proteins express I-E molecules. I/LnJ mice have two endogenous Mtv: Mtv7 and Mtv17 (data not shown). The Mtv7 endogenous provirus interacts with Vβ6+ and Vβ8.2+ T cells (30), and mice inheriting Mtv7 lack these T-cell subsets due to negative selection (20, 30). Indeed, flow cytometry analysis of peripheral blood lymphocytes stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-Vβ6 antibodies revealed only 0.6% of CD4+-Vβ6+ T cells in the immune repertoire of Mtv7-bearing I/LnJ mice, whereas 10 to 12% of CD4+ T cells were Vβ6+ in Mtv7-negative mice (20). Thus, the H-2j MHC class II molecules of I/LnJ mice can present endogenous Mtv.

Exogenous MMTVs are transmitted via milk. After newborn pups ingest milk containing MMTV particles, the virus is taken up in the gut. The primary targets for MMTV are probably B cells present in the intestinal environment, including Peyer's patches (26, 29). Once MMTV has integrated into the host genome and the sag gene in the 3′ LTR is transcribed, SAgs are produced. Subsequently, infected B cells present viral SAg on their surface in the context of MHC class II molecules to the cognate Vβ+ T cells, leading to specific T-cell proliferation. The activated T cells transmit proliferation signals to the B cells and thereby amplify MMTV infection. Later, these activated T cells undergo clonal deletion (32). SAg of exogenous MMTV(C3H) virus interacts with Vβ14+ T cells (15) and therefore, mice successfully infected with MMTV(C3H) show a slow progressive loss of their Vβ14+ T cells (32).

To test whether I/LnJ mice can present and respond to the exogenous viral SAg, newborn I/LnJ pups were foster nursed on C3H/HeN MMTV+ females, and the percentage of CD4+/Vβ14+ T cells in the periphery was analyzed at different ages. A slow progressive loss of CD4+/Vβ14+ T cells was seen in fostered I/LnJ mice as they aged, similar to that observed in C3H/HeN MMTV+ mice (H-2k haplotype), indicating that SAg of exogenous MMTV was efficiently presented by the MHC class II molecules with the H-2j haplotype (Fig. 1). By 6 weeks, 50% of the CD4+/Vβ14+ T cells were deleted in both I/LnJ and C3H/HeN mice nursed on the same viremic females (Fig. 1). Analysis of the frequency of SAg-cognate T cells in the thymus of I/LnJ mice revealed 12% of CD4+/Vβ14+ cells in uninfected I/LnJ mice, but only 5.6% of CD4+/Vβ14+ cells in chronically infected 4-month-old I/LnJ mice. Therefore, MMTV(C3H) SAg is presented by the MHC class II molecules with the H-2j haplotype and interacts with SAg-responsive T cells in I/LnJ mice.

FIG. 1.

Deletion of CD4+/Vβ14+ T cells in I/LnJ mice foster nursed on C3H/HeN MMTV+ mice. Kinetics of the Vβ repertoire of peripheral CD4+ T cells from I/LnJ and C3H/HeN mice foster nursed on C3H/HeN MMTV+ females are shown. Five mice were used at each data collection point. Data are expressed as means and standard deviations. I/LnJ f C3H/HeN MMTV+, I/LnJ mice foster nursed on viremic C3H/HeN females.

Primary lymphoid cells from neonatally infected I/LnJ mice contain integrated MMTV DNA and shed virus.

Nonquantitative PCR analysis of DNA isolated from spleens of I/LnJ mice foster nursed on viremic C3H/HeN females using MMTV(C3H)-specific primers revealed integrated MMTV proviruses in all infected I/LnJ mice (Fig. 2A). As a positive control, we used MMTV-infected congenic C3H.JK-H2j mice (hereafter termed C3H.JK), which are identical to C3H/He mice except for the MHC locus derived from I/LnJ. To determine whether the virus load in I/LnJ was similar to that in infected C3H/HeN or C3H.JK mice, semiquantitative PCR analysis was performed with the same DNA samples. The virus load in I/LnJ mice did not differ from that in the other infected susceptible strains (Fig. 2A). In addition, both B and T cells were infected equally in I/LnJ, C3H.JK MMTV+, and C3H/HeN MMTV+ mice (Fig. 2B).

To determine whether I/LnJ lymphocytes were productively infected by MMTV, we assayed supernatants from equal numbers of cultured splenocytes isolated from MMTV(C3H)-infected I/LnJ and C3H/HeN mice for the presence of virus. RNA isolated from viral particles pelleted from the filtered supernatants was subjected to RT-PCR analysis. MMTV-specific RNA was detected in the supernatants from infected I/LnJ mice (Fig. 2C). Thus, the lymphocytes of I/LnJ mice nursed on C3H/HeN MMTV+ females became productively infected, as indicated by the deletion of SAg-reactive T cells (Fig. 1), by acquisition of MMTV(C3H) proviral copies, and by virus production (Fig. 2).

Impaired mammary gland infection in I/LnJ mice foster nursed on viremic C3H/HeN females.

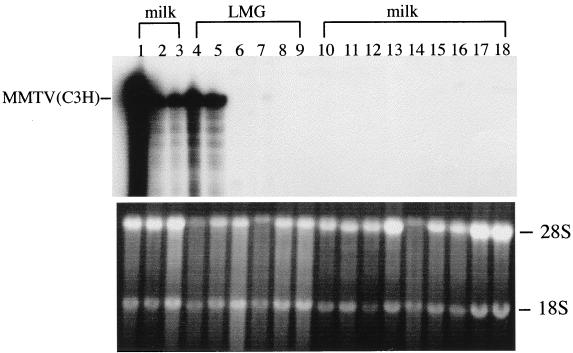

To test whether the mammary glands of I/LnJ mice foster nursed on viremic C3H/HeN females were infected and whether the virus was present in milk, RNA isolated from their lactating mammary glands and the milk was examined by RNase T1 protection analysis with the MMTV(C3H)-specific probe (25). The probe spans the region encoding the C terminus of the MMTV SAg protein, which shows the least homology among different SAgs (13). No MMTV(C3H)-specific RNA was detected in either the mammary glands or milk of any I/LnJ females nursed on viremic mothers even after the third pregnancy (Fig. 3, lanes 6 to 17), whereas milk samples of C3H/HeN mice nursed on the same mothers contained large amounts of viral RNA (Fig. 3, lanes 1 to 5). These results indicate that MMTV infection does not progress to the mammary glands of I/LnJ mice. Although it is possible that epithelial cells of I/LnJ mammary glands do not express the viral receptor, this explanation seems unlikely, since Nandi et al. (34) showed that the mammary glands of these mice can be infected when placed into mammary parenchyma-free fat pads of susceptible (C57BL × I)F1 hybrids.

FIG. 3.

Absence of MMTV infection in the mammary gland of I/LnJ mice foster nursed on C3H/HeN MMTV+ females. RNA isolated from the lactating mammary glands (LMG) (lanes 4 to 9) or milk (lanes 1 to 3 and 10 to 18) of I/LnJ (lanes 6 to 17) or C3H/HeN (lanes 1 to 5) mice foster nursed on C3H/HeN MMTV+ was subjected to RNase T1 protection analysis. Lane 18, RNA isolated from the milk of uninfected I/LnJ mice. Protection [MMTV(C3H)] corresponds to MMTV(C3H)-specific RNA. All mice were analyzed after their third pregnancy.

Mammary gland infection could be impaired if the H-2j haplotype of MHC class II molecules somehow hinders the normal spread of virus within the mammary gland. It was recently shown that SAg activity is required for MMTV spread within the mammary gland, and it was hypothesized that a cytokine(s) produced by SAg-stimulated T cells might induce the expression of gene products necessary for MMTV infection of mammary gland cells (24). Thus, SAg presentation by the MHC class II H-2j haplotype might not induce expression of some gene(s) required for the normal spread of MMTV within the mammary gland. To test this hypothesis, congenic C3H.JK mice were examined. Newborn C3H.JK mice were foster nursed on C3H/HeN MMTV+ females, and the percentages of CD4+/Vβ14+ T cells in the periphery were analyzed at different ages. In 8-week-old C3H.JK mice foster nursed on viremic C3H females, 55% of the CD4+/Vβ14+ T cells were deleted and their lymphocytes contained newly integrated MMTV proviruses (Fig. 2A), suggesting that their immune system was infected. RNase T1 protection analysis with the MMTV(C3H)-specific probe revealed large amounts of MMTV-specific RNA in samples isolated from their milk (Fig. 4A). Thus, the MHC class II H-2j haplotype does not affect normal MMTV spread within the mammary gland or virus secretion into the milk.

FIG. 4.

MMTV-infected I/LnJ lymphocytes fail to deliver virus to the mammary glands of susceptible (I × C3H.JK)F1 hybrid mice. (A) RNA was isolated from milk of C3H.JK and (I × C3H.JK)F1 females foster nursed on C3H/HeN MMTV+ females and subjected to RNase T1 protection analysis with a probe specific for MMTV(C3H). (I × C3H.JK)F1 and C3H.JK, milk RNA from uninfected (I × C3H.JK)F1 and C3H.JK mice, respectively. Mice were analyzed after their first pregnancy. (B) (Top) RNA was isolated from the milk of C3H.JK mice inoculated intraperitoneally with I/LnJ MMTV+ splenocytes and subjected to RNase T1 protection analysis with a probe specific for MMTV(C3H). RNA isolated from the milk of C3H.JK mice inoculated with C3H.JK MMTV+ splenocytes was used as a positive control. (Bottom) The same RNA samples run on a 1% formaldehyde gel were stained with ethidium bromide to verify their integrity. All mice were analyzed after their second pregnancy.

MMTV-infected I/LnJ lymphocytes fail to deliver virus to the mammary glands of susceptible (I × C3H.JK)F1 mice.

Although mice naturally acquire MMTV through milk, the virus can also be introduced by the transfer of lymphocytes isolated from infected syngeneic mice (41). To test whether the impaired mammary gland infection in I/LnJ mice reflected the inability of I/LnJ lymphocytes to spread MMTV within the mammary gland, lymphocytes (5 · 106 cells) isolated from spleens of infected I/LnJ (H-2j) mice were adoptively transferred to 3-week-old susceptible (I × C3H.JK)F1 (H-2j) females by intraperitoneal injection. The recipient F1 females were bred, and RNA was isolated from their milk. It has previously been shown that infection of mammary gland tissue increases with parity (21). Therefore, to ensure ample time for virus amplification, all mice were analyzed after their second pregnancy. Positive control C3H.JK mice received 5 · 106 lymphocytes isolated from the spleens of C3H.JK MMTV+ mice. Even though mammary glands of F1 hybrid females fostered on viremic C3H/HeN mothers were susceptible to MMTV infection and shed virus into the milk (Fig. 4A), RNA isolated from the milk of F1 females inoculated with infected I/LnJ MMTV+ splenocytes contained no detectable MMTV(C3H)-specific RNA (Fig. 4B). At the same time, C3H.JK mice inoculated with C3H.JK MMTV+ splenocytes produced virus, as evidenced by MMTV-specific RNA detected in their milk. Thus, although I/LnJ lymphocytes are productively infected with MMTV, they failed to establish infection in the mammary gland of susceptible mice.

Both impaired mammary gland infection and resistance to mammary tumors in I/LnJ mice are inherited as recessive traits.

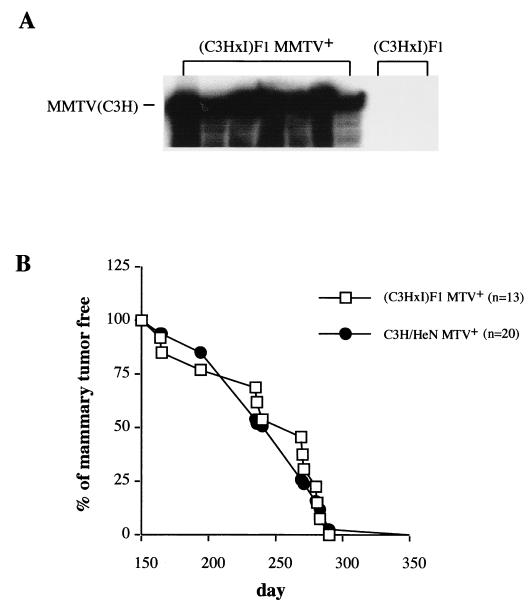

The data described in the preceding sections demonstrated that MMTV infection does not progress to the mammary gland of infected I/LnJ mice. To determine whether the resistance of I/LnJ strain mice to MMTV infection and subsequent tumor development is inherited as a Mendelian trait, we examined crosses between susceptible C3H/HeN MMTV+ females and resistant I/LnJ males. We chose to use C3H/HeN instead of C3H.JK mice for these studies, because C3H.JK mice were originally derived from C3H/HeJ mice, which exhibit attenuated mammary tumorigenesis (38). C3H/HeN MMTV+ females were crossed to I/LnJ males. The F1 female mice derived from these crosses were as susceptible as C3H/HeN MMTV+ mice to MMTV mammary gland infection (Fig. 5A) and MMTV-induced mammary tumor development (Fig. 5B). Thus, both resistance to MMTV mammary gland infection and MMTV-induced mammary tumors in I/LnJ mice are inherited as recessive traits.

FIG. 5.

Impaired mammary gland infection and susceptibility to MMTV-induced mammary tumors are inherited as recessive traits. (A) Infected C3H/HeN females were crossed to I/LnJ males. RNA was isolated from the milk of resulting infected (C3H × I)F1 females and subjected to RNase T1 protection analysis with a probe specific for MMTV(C3H). RNA isolated from the milk of uninfected (C3H × I)F1 females was used as a negative control. (B) Infected (C3H × I)F1 females as well as parental C3H/HeN MMTV+ females were bred and monitored for mammary gland tumors. All animals developed tumors by 290 days. n, number of mice used.

The impaired mammary gland infection in I/LnJ mice is controlled by a single locus.

To determine whether the impaired mammary gland infection in I/LnJ mice is inherited as a Mendelian trait, we backcrossed infected, susceptible (C3H/HeN × I/LnJ)F1 females to resistant I/LnJ males (Fig. 6). Since F1 hybrid females were susceptible to MMTV infection and produced virus into the milk (Fig. 5A), their offspring (generation N2) mice received virus through the milk. At puberty, N2 females were bred, and RNA was isolated from their milk after the first pregnancy and subjected to RNase T1 analysis with the MMTV(C3H)-specific probe. Fifty of the 102 N2 females analyzed had infected mammary glands and produced virus into the milk, and 52 N2 females did not have infected mammary glands (Fig. 6; 17 N2 females are shown). We have noticed some deviations in the amount of virus produced by different N2 females; however, the virus produced is within the range of variation normally observed in C3H/HeN MMTV+ females (data not shown). This 1:1 distribution suggests that only one gene controls the impaired mammary gland infection in I/LnJ mice. These mice were monitored for mammary gland tumor development. In our C3H/HeN MMTV+ colony, 10 months is defined as latency time when 99% of the females develop mammary tumors. All but one of the susceptible N2 mice (12 of 13; 26 total) developed mammary gland tumors by 10 months, and none of the resistant N2 females (0 of 13) developed mammary tumors by that time. Therefore, in I/LnJ mice resistance to both MMTV mammary gland infection and tumorigenesis is controlled by a single locus.

FIG. 6.

Both impaired MMTV mammary gland infection and subsequent tumorigenesis are controlled by a single locus. Hybrid (C3H/HeN × I/LnJ)F1 infected females were backcrossed to I/LnJ males. The resulting N2 females were bred and RNA was isolated from their milk and subjected to RNase T1 protection analysis with a MMTV(C3H)-specific probe. Lanes 1 to 17, RNA isolated from the milk of the infected N2 females. Mice were analyzed after their first pregnancy. All but one MMTV-infected N2 females developed mammary tumors by 10 months.

DISCUSSION

Susceptible mice infected with MMTV secrete viral particles into the milk and transmit them to their offspring. B and T cells are the targets for the virus in the immune system of neonatally infected pups, and they deliver the virus to the mammary glands. Both lymphocyte subsets can produce infectious viral particles (19) and are also necessary for MMTV spread within the mammary gland (24), where tumors are induced after MMTV integration next to a cellular proto-oncogene (37). In contrast to susceptible C3H/He animals, mice of the I/LnJ strain are highly resistant to mammary gland tumor development, even when the young receive MMTV at birth (5). However, when mammary gland tissues from I/LnJ mice are transplanted into an infected susceptible (C57BL/6 × I)F1 hybrid, they form large numbers of precancerous nodules and tumors upon hormonal treatment (34, 35). These nodules and tumors contained MMTV particles (34, 35). Therefore, mammary tissues of I/LnJ mice do express the MMTV receptor and are susceptible to MMTV infection and subsequent tumorigenesis. My data suggest that abrogation of the MMTV life cycle is a key to the absence of tumors in this strain of mice.

The block of the viral life cycle may occur at several levels: presentation of SAg to T cells leading to the failure of amplification within the immune compartment, infection of T and B lymphocytes, migration of T and B cells to the mammary gland, virus production by lymphocytes, and the spread of infection within the mammary epithelium. We demonstrated that MMTV(C3H) SAg is efficiently presented by MHC class II molecules with the H-2j haplotype and interacts with SAg-responsive T cells in I/LnJ mice (Fig. 1). In addition, C3H.JK mice which express the same MHC haplotype as I/LnJ mice are readily infected with MMTV and produce virus in milk (Fig. 4A). Therefore, the mechanism of resistance to MMTV infection in I/LnJ mice does not rest in the MHC locus and thus is different from that in C57BL/6 mice. Indeed, the progeny of crosses between these two resistant strains are susceptible to MMTV infection and consequent tumorigenesis (34, 35).

We found next that lymphocytes from I/LnJ mice foster nursed on viremic C3H/HeN females are productively infected with MMTV (Fig. 2). Moreover, the virus load in the immune compartment of infected I/LnJ mice does not differ significantly from that in infected, susceptible C3H.JK and C3H/HeN mice (Fig. 2). The small difference observed in virus production between I/LnJ and C3H/HeN lymphocytes cannot account for the failure to infect the mammary gland in I/LnJ mice. MMTV mammary gland infection in C57BL/6J (I-E−) mice becomes evident by the second pregnancy and reaches the same levels as in C3H/HeN mice by the third pregnancy (42), even though virus amplification within the immune system compartment occurs at much lower levels than in C3H/HeN mice (data not shown). In contrast, MMTV-infected I/LnJ mice do not produce virus into the milk even after the fourth pregnancy (data not shown). Therefore, it becomes apparent that the block of the MMTV cycle in I/LnJ mice is at the level of transmission of the virus from lymphocytes to the mammary epithelium.

Several mechanisms (however, the list may not be complete) may account for the impaired virus transmission to the mammary gland. First, it is possible that homing of lymphocytes to the mammary gland might be affected in I/LnJ mice by mutation(s) in chemokines, chemokine receptors, or adhesion molecules. Lymphocyte homing is based on multiple interactions of adhesion molecules and their ligands that may be both homophylic and heterophylic (14). We found that I/LnJ MMTV-infected lymphocytes fail to deliver virus to the mammary gland of susceptible (I × C3H.JK)F1 mice (Fig. 4B). In contrast, the I/LnJ mammary epithelium becomes infected with MMTV when placed under the mammary parenchyma-free fat pads of susceptible (C57BL/6 × I)F1 MMTV+ hybrids (34, 35). Thus, resistance to infection in I/LnJ mice might be due to the lack of homophilic interaction between some molecule (factor X, mutated in I/LnJ mice) expressed on the cell surface of MMTV-infected B or T cells and some other cells surrounding the mammary gland (for instance, stromal connective tissue).

Second, it is also possible that I/LnJ mice may produce an efficient cellular or humoral immune response against MMTV. However, the immune system of adult I/LnJ mice is not cleared of the virus (Fig. 2), suggesting that the virus source is not eliminated by the immune response. Neutralizing antibodies are an unlikely factor, as they are easily found in animals that have successful MMTV infection (3). Whatever the mechanism of tumor resistance in I/LnJ mice, it is likely to be determined by identification of the controlling gene. Based on distribution of the milk virus production phenotype in infected N2 females obtained from crosses between susceptible infected (C3H/HeN × I/LnJ)F1 females and resistant I/LnJ males, the impaired mammary gland infection in I/LnJ mice is controlled by a single locus (Fig. 6). Since only virus-producing mice succumbed to mammary tumors (Fig. 6), it appears that a single gene controls susceptibility to virus-induced mammary tumorigenesis via blockade of the infection of mammary epithelium.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I thank Sharon Overlock for excellent technical assistance and Alexander V. Chervonsky and Susan R. Ross for helpful discussion.

This work was supported in part by a grant from the V Foundation, by Public Health Service grants CA65795 and CA34196, and by a grant from The Jackson Laboratory (TOTVG). This work was also supported by grant CA34196 from the National Cancer Institute to the Jackson Laboratory.

REFERENCES

- 1.Acha-Orbea H, Shakhov A N, Scarpellino L, Kolb E, Muller V, Vessaz Shaw A, Fuchs R, Blochlinger K, Rollini P, Billotte J, Sarafidou M, MacDonald H R, Diggelmann H. Clonal deletion of V beta 14-bearing T cells in mice transgenic for mammary tumour virus. Nature. 1991;350:207–211. doi: 10.1038/350207a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Acha-Orbea H, MacDonald H R. Superantigens of mouse mammary tumor virus. Annu Rev Immunol. 1995;13:459–486. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.13.040195.002331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altrock B W, Cardiff R D, Blair P B. Murine mammary tumor virus seroepidemiology in BALB/cfC3H mice: correlation with tumor development. JNCI. 1981;67:163–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andervont H, Stewart H. Adenomatous lesion in the stomach of strain I mice. Science. 1937;86:566–567. doi: 10.1126/science.86.2242.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andervont H B. Fate of the C3H mammary tumor agent in mice of strains C57BL, I, and BALB/c. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1964;32:1189–1198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andervont H B. Further studies on the susceptibility of hybrid mice to induced and spontaneous tumors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1940;1:135–145. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andervont H B. The influence of foster nursing upon the incidence of spontaneous mammary cancer in resistant and susceptible mice. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1940;1:147–153. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andervont H B. Influence of hybridization upon the occurrence of mammary tumors in mice. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1943;3:359–365. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andervont H B. The use of pure strain animals in studies on natural resistance to transplantable tumors. Public Health Rep. 1937;52:1885–1895. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Begovich A B, Vu T H, Jones P P. Characterization of the molecular defects in the mouse Ebf and Ebq genes. Implications for the origin of MHC polymorphism. J Immunol. 1990;144:1957–1964. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beutner U, Kraus E, Kitamura D, Rajewsky K, Huber B T. B cells are essential for murine mammary tumor virus transmission, but not for presentation of endogenous superantigens. J Exp Med. 1994;179:1457–1466. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.5.1457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bittner J J. Genetic concepts in mammary cancer in mice. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1958;71:943–975. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1958.tb46816.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brandt-Carlson C, Butel J S, Wheeler D. Phylogenetic and structural analysis of MMTV LTR ORF sequences of exogenous and endogenous origins. Virology. 1993;185:171–185. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Butcher E C, Picker L J. Lymphocyte homing and homeostasis. Science. 1996;272:60–66. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5258.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choi Y, Kappler J W, Marrack P. A superantigen encoded in the open reading frame of the 3′ long terminal repeat of the mouse mammary tumor virus. Nature. 1991;350:203–207. doi: 10.1038/350203a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coffin J M. Retroviridae: the viruses and their replication. 3rd ed. New York, N.Y: Raven Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dembic Z, Ayane M, Klein J, Steinmetz M, Benoist C O, Mathis D J. Inbred and wild mice carry identical deletions in their E alpha MHC genes. EMBO J. 1985;4:127–131. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb02326.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dux A, Demant P. MHC-controlled susceptibility to C3H-MTV-induced mouse mammary tumors is predominantly systemic rather than local. Int J Cancer. 1987;40:372–377. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910400315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dzuris J, Golovkina T V, Ross S R. Both T and B cells shed infectious mouse mammary tumor virus. J Virol. 1997;71:6044–6048. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.8.6044-6048.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frankel W N, Rudy C, Coffin J M, Huber B T. Linkage of Mls genes to endogenous mammary tumour viruses of inbred mice. Nature. 1991;349:526–528. doi: 10.1038/349526a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Golovkina T, Prescott J, Ross S. Mouse mammary tumor virus-induced tumorigenesis in sag transgenic mice: a laboratory model of natural selection. J Virol. 1993;67:7690–7694. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.12.7690-7694.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Golovkina T V, Chervonsky A, Prescott J A, Janeway C A, Ross S R. The mouse mammary tumor virus envelope gene product is required for superantigen presentation to T cells. J Exp Med. 1994;179:439–446. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.2.439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Golovkina T V, Chervonsky A V, Dudley J P, Ross S R. Transgenic mouse mammary tumor virus superantigen expression prevents viral infection. Cell. 1992;69:637–645. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90227-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Golovkina T V, Dudley J P, Ross S R. B and T cells are required for mouse mammary tumor virus spread within the mammary gland. J Immunol. 1998;161:2375–2382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Golovkina T V, Jaffe A B, Ross S R. Coexpression of exogenous and endogenous mouse mammary tumor virus RNA in vivo results in viral recombination and broadens the virus host range. J Virol. 1994;68:5019–5026. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.8.5019-5026.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Golovkina T V, Shlomchik M, Hannum L, Chervonsky A. Organogenic role of B lymphocytes in mucosal immunity. Science. 1999;286:1965–1968. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5446.1965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Held W, Waanders G, Shakhov A N, Scarpellino L, Acha-Orbea H, MacDonald H R. Superantigen-induced immune stimulation amplifies mouse mammary tumor virus infection and allows virus transmission. Cell. 1993;74:529–540. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80054-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Held W, Waanders G A, MacDonald H R, Acha Orbea H. MHC class II hierarchy of superantigen presentation predicts efficiency of infection with mouse mammary tumor virus. Int Immunol. 1994;6:1403–1407. doi: 10.1093/intimm/6.9.1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karapetian O, Shakhov A N, Kraehenbuhl J P, Acha Orbea H. Retroviral infection of neonatal Peyer's patch lymphocytes: the mouse mammary tumor virus model. J Exp Med. 1994;180:1511–1516. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.4.1511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.MacDonald H R, Glasebrook A L, Schneider R, Lees R K, Pircher H, Pedrazzini T, Kanagawa O, Nicolas J F, Howe R C, Zinkernagel R M, Hengartner H. T-cell reactivity and tolerance to Mlsa-encoded antigens. Immunol Rev. 1989;107:89–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1989.tb00004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.MacDonald H R, Schneider R, Lees R K, Howe R C, Acha Orbea H, Festenstein H, Zinkernagel R M, Hengartner H. T-cell receptor V beta use predicts reactivity and tolerance to Mlsa-encoded antigens. Nature. 1988;332:40–45. doi: 10.1038/332040a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marrack P, Kushnir E, Kappler J. A maternally inherited superantigen encoded by mammary tumor virus. Nature. 1991;349:524–526. doi: 10.1038/349524a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Muhlbock O, Dux A. Histocompatability genes and mammary cancer. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier/North-Holland Biomedical Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nandi S, Handin M, Robinson A, Pitelka D R, Webber L E. Susceptibility of mammary tissues of “genetically resistant” strains of mice to mammary tumor virus. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1966;36:783–801. doi: 10.1093/jnci/36.4.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nandi S, Haslam S, Helmich C. Mechanisms of resistance to mammary tumor development in C57BL and I strains of mice. I. Noduligenesis, tumorigenesis, and characteristics of nodules and tumors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1972;48:1005–1012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nandi S, McGrath C M. Mammary neoplasia in mice. Adv Cancer Res. 1973;17:353–414. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nusse R. The int genes in mammary tumorigenesis and in normal development. Trends Genet. 1988;4:291–295. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(88)90172-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Outzen H C, Corrow D, Shultz L D. Attenuation of exogenous murine mammary tumor virus in the C3H/HeJ mouse substrain bearing the Lps mutation. JNCI. 1985;75:917–923. doi: 10.1093/jnci/75.5.917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pucillo C, Cepeda R, Hodes R J. Expression of a MHC class II transgene determines both superantigenicity and susceptibility to mammary tumor virus infection. J Exp Med. 1993;178:1441–1445. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.4.1441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shackleford G M, Varmus H E. Construction of a clonable, infectious and tumorigenic mouse mammary tumor virus provirus and a derivative genetic vector. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:9655–9659. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.24.9655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Waanders G A, Shakhov A N, Held W, Karapetian O, Acha-Orbea H, MacDonald H R. Peripheral T cell activation and deletion induced by transfer of lymphocytes subsets expressing endogenous or exogenous mouse mammary tumor virus. J Exp Med. 1993;177:1359–1366. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.5.1359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wrona T, Dudley J P. Major histocompatibility complex class II I-E-independent transmission of C3H mouse mammary tumor virus. J Virol. 1996;70:1246–1249. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.2.1246-1249.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yamamoto K. Steroid receptor regulated transcription of specific genes and gene networks. Annu Rev Genet. 1985;19:209–252. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.19.120185.001233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]