Abstract

Consumer engagement and partnership are increasingly recognised as a significant component of healthcare planning, provision, quality improvement and research. This article provides an overview of consumer engagement embedded in two different projects: a quality improvement project and a research project. The considerations and steps taken to effectively engage and partner with consumers throughout both projects will be discussed such as the prompt for consumer engagement, how the consumer/s were recruited and their specific contributions. The commonly reported advantages and challenges as well as reflections on what we might do differently with the benefit of hindsight are presented, including time required by both consumers and health professionals; funding and remuneration; and reporting findings to the wider community. In demonstrating consumer engagement and our learnings, we aim to encourage further consumer engagement activities amongst medical radiation professionals.

Keywords: Consumer and community involvement, quality improvement, radiotherapy, research

This article describes how we incorporated consumer engagement into a quality improvement activity and a research study. In demonstrating consumer engagement steps, considerations and our learnings, we aim to encourage further consumer engagement activities amongst medical radiation professionals.

Background

There is a recognised need and increasing expectation for effective consumer engagement in healthcare. 1 , 2 , 3 Partnering with consumers, a standard within the Australian National Safety and Quality Health Service, covers the concepts of engaging and partnering with consumers and the community. Additionally, it needs to be ‘a basic element in discussions and decisions about the design, implementation and evaluation of health policies, programs and services’. 1 Consumer engagement and partnership can happen on many levels within healthcare, from informing to initiating or leading projects. 4 , 5 Figure 1 illustrates examples of the levels of involvement, increasing commitment and other considerations required for different levels of engagement. The commonly reported benefits and challenges for consumer engagement in quality improvement and research activities are summarised in Table 1.

Figure 1.

The various levels of consumer engagement, highlighting examples of what these levels might involve.

Table 1.

The commonly reported benefits and challenges of consumer engagement in quality improvement and research activities.

| Benefits 8 , 9 , 10 | Challenges 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 |

|---|---|

|

|

Engaging and partnering with consumers in developing and conducting quality improvement projects and research ensures that community priorities and consumer relevance are considered and incorporated. 6 There is national momentum through the recently released National Clinical Trials Governance Framework, of which one of the five components is partnering with consumers. 7 With consumer partnership in clinical trials now to be assessed at accreditation, consumer engagement is a vital component for all health professionals to consider in the development and conduct of their research and quality improvement projects.

There are various terminologies used to describe consumer engagement and partnership in different jurisdictions, including but not limited to: patient or public involvement; lay collaborator; community expert; citizen scientist; client consultation; consumer partner/consumer partnering and indeed, several iterations of these terms. We will utilise the terms ‘consumer’ and ‘consumer engagement’ for this article.

We write from the perspective of engaging consumers for two different projects in two different health services within Queensland: a quality improvement project developing an educational resource for adolescents and young adults (AYAs) who require radiation therapy (RT) treatment and a research study investigating patient preferences for image‐guidance in RT.

This article aims to demonstrate consumer engagement in action by drawing on our experiences throughout the two projects as case studies. We acknowledge that while our two case studies are based within RT and that there are nuances present between healthcare provision for medical imaging and RT professions, we believe that the information we present is valuable for any medical radiation professional (MRP) considering consumer engagement.

Case Study 1

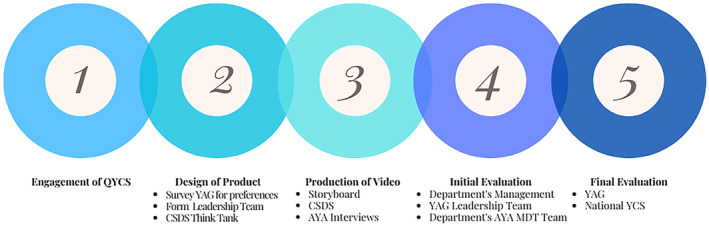

There is a crucial need to prioritise and improve radiation therapy education resources for AYAs. This patient cohort faces various disadvantages due to poorly developed health models of care not meeting this population's unique needs. 17 , 18 , 19 Whilst the use of multimedia in providing patient education is well supported throughout the literature, in 2021, no RT education resource had been created and was available for young people in Australia. To appropriately and successfully design a resource tailored for AYA cancer patients, we harnessed a collaborative framework promoting early consumer engagement and employed co‐design principles (Table 2). Figure 2 depicts our consumer and stakeholder co‐design processes, steps 1–5, highlighting the multifaceted design and evaluation with our target audience and broadly with professional streams who provide care to AYA oncology patients across Queensland. From step 1, this project utilised a partnership with the Queensland Youth Cancer Service (QYCS) and their Youth Advisory Group (YAG) (Table 3). Steps 2 and 3 allowed the formation and development of the resource in partnership with the Metro North Hospital and Health Service Clinical Skills Development Service (CSDS). Step 2 engaged seven AYA consumers (58% response rate) in a survey exploring RT education needs including design, style and essential topics for inclusion in the resource. Their feedback suggested that a general overview of RT was essential and that the inclusion of patient stories was important. From this group, two young consumers joined two radiation therapists to form the project leadership team. Step 3 consisted of the project leadership team meeting on a monthly basis to design the resource using the results from the stage 2 survey and each member's expertise. Patient experiences were also recorded with four young patients who had undergone RT treatment in Queensland. During steps 4 and 5, the production and finalisation of the resource were evaluated via surveys and direct feedback within our department; the YAG; through our region's AYA Multidisciplinary Team (MDT); and more broadly through the National Youth Cancer Service (YCS). This included 15 submissions of formal survey feedback (22% response rate) and approximately 20 feedback submissions via email, telephone and in‐person. These networks are made up of multidisciplinary health professionals from multiple service sites providing care to oncology patients, young patients and families. Feedback from this stage of consultation provided valuable insight to improve the drafted resource's design and the results supported the adoption of the resource in clinical education practices for RT.

Table 2.

Overview of the processes for case study 1 (quality improvement project) and case study 2 (research project).

| Case Study 1: Harnessing the power of consumer co‐design to create multimedia patient education resources for AYA patients who require radiation therapy | Case Study 2: Preferences for Image‐guidance in prostate cancer radiation therapy | |

| Type of Project | A quality improvement project with ethics exemption | A research study, with ethics approval |

| Who was involved |

2 Radiation Therapists in Project Leadership Team 2 Consumers in Project Leadership Team 1 Allied Health Research Coordinator 7 Consumers participated in design and content proposals |

Principle Investigator (PI): A Radiation Therapist PhD Candidate 5 PhD Supervisors (both clinical and academic) 1 Consumer Investigator |

| What prompted consumer engagement | Our target audience was the catalyst for consumer engagement and strong advocacy within the sector to engage AYA consumers in all aspects of health improvement work. 22 | Suggestion by an academic supervisor, as this was standard practice at their institution for patient preference methodology |

| Consumer involvement (Fig. 1) | Collaborate | Collaborate |

| Requirement for ‘right’ consumer |

Design of Product: Any AYA with experience in oncology previously provided with education materials about cancer treatment. Leadership Team: Former AYA RT patients who had the capacity to meet monthly for 6 months. AYA Interviews: 4 former AYA RT patients who desired to share their treatment experiences |

Lived experience, specifically: a patient with prostate cancer who had recently undergone radiation therapy treatment with image‐guidance |

| How consumer/s were recruited | Through collaboration with the Queensland Youth Cancer Service (QYCS) Youth Advisory Group (YAG) | A shortlist of patients who had recently completed treatment at the department was compiled by the PI and clinical supervisor/co‐investigator. A brief letter of introduction was sent out, with a follow‐up telephone call by the PI |

| Specific Considerations |

|

|

| Funding | Project funding was secured through the Metro North Health Collaborative for Allied Health Research, Learning and Innovation (CAHRLI) | Hospital research grant awarded included parking costs for consumers and costs (travel, accommodation and registration) for co‐presenting at a conference |

| Final outcome and/or output |

Two video resources used locally and across the state: CCS Radiotherapy overview for adolescent and young adult (AYA) patients on Vimeo 1 Radiation Therapy – TBI from CSDS on Vimeo 2 |

Two research publications Three conference presentations with consumer videos incorporated |

AYA, adolescents and young adults; CSDS, Clinical Skills Development Service; MDT, Multidisciplinary Team; PhD, Doctor of Philosophy; PI, Principal Investigator; QLD, Queensland; QYCS, Queensland Youth Cancer Service; YAG, Youth Advisory Group.

Figure 2.

Consumer and stakeholder co‐design strategy—the five key steps in the process. AYA, adolescents and young adults; CSDS, Clinical Skills Development Service; MDT, Multidisciplinary Team; QLD, Queensland; QYCS, Queensland Youth Cancer Service; YAG, Youth Advisory Group.

Table 3.

Specific contributions and reflections of the consumers.

| Case Study 1: Harnessing the power of consumer co‐design to create multimedia patient education resources for AYA patients who require radiation therapy | Case Study 2: Preferences for Image‐guidance in prostate cancer radiation therapy | |

| Specific Contributions of the Consumer/s |

1. YAG contribution: Provided feedback on design of the product and final evaluation via surveys. 2. Project Leadership Team:

3. AYA Interviews: Lived experience of radiation therapy treatment shared via recorded interviews |

The consumer was a named co‐investigator on all study‐related material, including protocol, ethics and governance applications etc; and the study outputs including presentation and publications. Contributed to:

|

| Reflection of consumer representative |

‘I did not find radiation therapy easy but being a part of this project has been cathartic and empowering for me.’ ‘This project has been very inclusive, and I am impressed with the quality of what we have produced’ |

‘It's enlightened me to find out how much effort is put into the research that's done to help the patients, not just to do the job but to help the patient. They leave no stone unturned, and it makes me very happy to have been a part of that. It allowed me to voice my feelings as a layperson and it may make it better for other future patients’ |

Case Study 2

In the very early stages of developing a research study investigating the preferences for image‐guidance in prostate cancer RT, an academic supervisor on the project team suggested consumer engagement with the ideal goal of having a consumer join the research team. As it was a requirement to bring their lived experience to the project, a shortlist of patients meeting these criteria was compiled and a letter of invitation was sent out. From this, a consumer expressed interest in joining, with processes outlined in Table 2. While contributing to a PhD study, the research was embedded in clinical practice, thus approvals for ethics and governance were obtained through the hospital and health service (HHS) along with acknowledgement approval from the university. The consumer joined at the stage of developing the research protocol and actively contributed to all stages of the project (Table 3). This resulted in two publications with the consumer as a co‐author. 20 , 21 Initial plans were for the consumer investigator to co‐present findings at professional conferences. However, this was altered due to the COVID‐19 pandemic which resulted in conferences either being cancelled or migrating to a virtual format. Therefore, three virtual conference presentations, in which the consumer provided insights through embedded videos, were delivered to clinical and/or researcher audiences.

Reflections and Learnings

Through our collective experiences in consumer engagement, we can reflect on the learnings and offer suggestions for other MRPs to take forward in their engagement with consumers.

Clear guidelines and support

It was evident that there are varying levels of consumer engagement guidelines across the two major HHSs where the two case study projects were conducted. The existing HHS guidelines and support provided focused on consumer engagement within day‐to‐day hospital activities such as consumer representatives sitting on hospital committees or within working groups.

We suggest that any MRP considering consumer engagement for a project, to first liaise with their consumer engagement representative if one exists in their organisation. Other avenues of information and support could include state‐based consumer reference guides and groups such as the Department of Health Consumer Engagement Guide and Health Consumers Queensland. 3 , 23

In the setting of a research project, early consultation with organisational ethics and governance offices is highly recommended to ensure the necessary requirements are met. In case study 2, as previously mentioned, there were organisational guidelines regarding consumer involvement in regular hospital activities but not specifically for research which required liaising with both the consumer engagement representative and the research unit.

It may also be necessary to train or upskill the consumer to ensure they feel empowered and comfortable contributing to the project; for example, supply specific readings about the health condition or health services being investigated or provide training regarding the project methods. Some health services and organisations may have an orientation program or specific consumer training available to the consumers, and in some cases, as a mandatory requirement. There is also consumer organisation training available to both consumers and researchers, valuable to those new to consumer engagement.

Time and remuneration/funding

Both case studies had significant time implications for the health professionals and consumers involved. The consumers' time in both case studies was completely voluntary. The project funding awarded in case study 1 covered in‐kind costs for the health professionals' time as part of departmental quality improvement activity but did not cover remuneration of the consumers. In case study 2, basic research training such as devising a protocol, ethics and governance applications as well as specifics around discrete choice experiment methodology and content‐analysis was required by both the consumer and the principal investigator which led to a significant time investment.

We firmly believe that the immeasurable value of consumers' lived experience should be formally acknowledged through remuneration in future projects. Indeed, whilst it would have been ideal to have consumer co‐author(s) for this paper, this was not pursued due to a lack of specific funding to remunerate their invested time in writing and reviewing. We strongly encourage MRPs to investigate every possible avenue to secure consumer remuneration so that consumers continue to feel empowered to contribute their time and expertise in improving the health system. Avenues of remuneration could be explored through the primary organisation, any supporting or collaborating organisations such as universities or specific consumer organisations, or through targeted funding opportunities.

Related to funding, there is an increasing emphasis on consumer engagement in competitive grant rounds. These include Category 1 grants such as the National Health and Medical Research Council and Medical Research Future Fund where consumers form a part of the peer review assessment panels, particularly for targeted research grants. 24 , 25 Applications for many major funding schemes now include a mandatory section on consumer engagement and/or involvement.

Unique consumer considerations

There are unique considerations in collaborating with consumers on projects such as privacy and confidentiality of data, intellectual property, their willingness to be recognised and associated with a particular health condition and potential power imbalances. 6

Depending on the project specifics, the team should carefully consider and discuss privacy and confidentiality. 6 Thus, a mechanism such as a confidentially agreement signed by all members of the project team is recommended. Moreover, if the consumer will be accessing identified and/or sensitive data, this needs appropriate ethics and governance approvals and incorporated into the confidentially agreement with participants informed accordingly as per standard consent procedures. The consumer(s) need an understanding that they are privy to information not yet widely known and formal intellectual property management may need to be considered.

Another consideration around privacy is the consumer's willingness to be recognised as associated with a particular health condition. 26 This needs to be an up‐front discussion with the option of pseudonyms explored in presentations and publications should the consumer not wish to be identifiable (subject to conference organisers and journal publishers allowing this). It is also important to note that not all consumer involvement will meet authorship guidelines, and an acknowledgement may be most appropriate. 27 , 28 Where authorship guidelines are met, the contributions, affiliation and roles of the consumers should be clearly identified as per the specific journal guidelines.

While uniquely placed to bring their lived experience to a project, consumers often feel a power imbalance in joining a team of health professionals and/or researchers. 29 Suggestions to mitigate this include a team member meeting the consumer(s) in person to introduce the project in a less intimidating setting, assigning a team member as the consumer's primary contact and mentor and all team members being open to hearing the opinions of the consumer in all key stages of the project.

What we might do differently next time

In both projects, we would seek further funding for remuneration of the consumers' time. At the start of both projects described in this article, there were limited or no organisational guidelines regarding this issue. Increasingly, there are specific organisational policies or guidelines around appropriate remuneration including gift cards, parking vouchers and recurrent payments for ongoing involvement, depending on the level of involvement and commitment expected to be contributed. One such example is the Health Consumers Queensland Position Statement, 30 which has been adopted by Queensland Health to guide consumer remuneration. 31

When preparing the funding application for case study 1, the MRS professionals underestimated the pivotal role the consumers would play in crafting and refining the end resources and did not apply for funding to remunerate the consumers. The MRS professionals were also advised that consumers do not have to be paid and can, of course, volunteer if that is clear in the terms of reference for the project. Executive approvals to purchase gift cards/parking vouchers and the significant administrative onboarding required to recurrently pay a consumer for ongoing involvement in a quality improvement activity are examples of other barriers that impact consumers' successful remuneration process.

In case study 2, a second consumer‐investigator may have been beneficial. This would have provided peer‐support and further alleviated the initial pressure the consumer investigator expressed as feeling like he had to speak for all prostate cancer patients.

Additionally, communicating and sharing our results to the wider community was not undertaken, and this could be a key component to enhance our partnership with consumers for future projects. Indeed, consumers could guide how to effectively facilitate this process within the community.

Conclusion

Consumer engagement considerably enriched both of the case studies presented. As such, we encourage all MRS professionals to consider how they can engage further with consumers in their work, particularly in quality improvement and research projects. Organisations must continue to improve consumer engagement and remuneration processes to better meet national standards in safety and quality health service delivery while supporting all health professionals to proactively embed lived expertise into our work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

Ethics exemption was granted for Case Study 1 and ethics approval was granted for Case Study 2 (Table 2).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the consumers who so generously gave their expertise and time to both of the case studies presented. Brianna and Yovanna acknowledge the contributions of Emilie Eadie to Case Study 1. Amy is thankful for the encouragement and support of her PhD supervisory team in embarking on consumer engagement.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed.

References

- 1. The National Safety and Quality Health Service Standards: Partnering with Consumers Standard. 2022. [Accessed May 19, 2023]. Available from: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/standards/nsqhs‐standards.

- 2. Consumer engagement | Cancer Australia. [Accessed May 19, 2023]. Available from: https://www.canceraustralia.gov.au/about‐us/who‐we‐work/consumer‐engagement.

- 3. Queensland Health . Partnering with consumers | Queensland Health Intranet. [Accessed May 19, 2023]. Available from: https://qheps.health.qld.gov.au/csd/business/consumer‐engagement/partnering‐with‐consumers.

- 4. Cancer Australia . National Framework for Consumer Involvement in Cancer Control. Published September 8, 2012. [Accessed May 23, 2023]. Available from: https://www.canceraustralia.gov.au/publications‐and‐resources/cancer‐australia‐publications/national‐framework‐consumer‐involvement‐cancer‐control.

- 5. Amirav I, Vandall‐Walker V, Rasiah J, Saunders L. Patient and researcher engagement in health research: a parent's perspective. Pediatrics 2017; 140: e20164127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. National Health and Medical Research Council . Statement on Consumer and Community Involvement in Health and Medical Research. 2016.

- 7. Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care . The National Clinical Trials Governance Framework and User Guide for Health Service Organisations Conducting Clinical Trials. ACSQHC. 2022. [Accessed October 11, 2023]. Available from: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/publications‐and‐resources/resource‐library/national‐clinical‐trials‐governance‐framework‐and‐user‐guide.

- 8. Manafo E, Petermann L, Mason‐Lai P, Vandall‐Walker V. Patient engagement in Canada: a scoping review of the ‘how’ and ‘what’ of patient engagement in health research. Health Res Policy Syst 2018; 16: 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Daykin N, Evans D, Petsoulas C, Sayers A. Evaluating the impact of patient and public involvement initiatives on UK health services: a systematic review. Evid Policy 2007; 3: 47–65. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Leese J, Macdonald G, Kerr S, et al. ‘Adding another spinning plate to an already busy life’. Benefits and risks in patient partner–researcher relationships: a qualitative study of patient partners' experiences in a Canadian health research setting. BMJ Open 2018; 8: e022154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Machin K, Shah P, Nicholls V, et al. Co‐producing rapid research: Strengths and challenges from a lived experience perspective. Front Sociol 2023; 8: 996585. [Accessed May 23, 2023]. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fsoc.2023.996585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Richards DP, Cobey KD, Proulx L, Dawson S, de Wit M, Toupin‐April K. Identifying potential barriers and solutions to patient partner compensation (payment) in research. Res Involv Engagem 2022; 8: 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cox R, Molineux M, Kendall M, Tanner B, Miller E. ‘Learning and growing together’: Exploring consumer partnerships in a PhD, an ethnographic study. Res Involv Engagem 2023; 9: 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Greenhalgh T, Hinton L, Finlay T, et al. Frameworks for supporting patient and public involvement in research: Systematic review and co‐design pilot. Health Expect 2019; 22: 785–801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Carlini J, Muir R, McLaren‐Kennedy A, Grealish L. Researcher perceptions of involving consumers in health research in Australia: A qualitative study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2023; 20: 5758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Anderst A, Conroy K, Fairbrother G, Hallam L, McPhail A, Taylor V. Engaging consumers in health research: A narrative review. Aust Health Rev 2020; 44: 806–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Australia C . National Service Delivery Framework for Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer. Published February 6, 2014. [Accessed May 19, 2023]. Available from: https://www.canceraustralia.gov.au/publications‐and‐resources/cancer‐australia‐publications/national‐service‐delivery‐framework‐adolescents‐and‐young‐adults‐cancer.

- 18. Ricadat É, Schwering KL, Fradkin S, Boissel N, Aujoulat I. Adolescents and young adults with cancer: How multidisciplinary health care teams adapt their practices to better meet their specific needs. Psychooncology 2019; 28: 1576–1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Psychosocial management of AYAs diagnosed with cancer: Guidance for health professionals – Cancer Guidelines Wiki. [Accessed May 19, 2023]. Available from: https://wiki.cancer.org.au/australia/COSA:Psychosocial_management_of_AYA_cancer_patients.

- 20. Brown A, Tan A, Anable L, Callander E, De Abreu Lourenco R, Pain T. Perceptions and recall of treatment for prostate cancer: A survey of two populations. Tech Innov Patient Support Radiat Oncol 2022; 24(September): 78–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Brown A, Pain T, Tan A, et al. Men's preferences for image‐guidance in prostate radiation therapy: A discrete choice experiment. Radiother Oncol 2022; 167(S1): 49–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Patterson P, Allison KR, Hornyak N, Woodward K, Johnson RH, Walczak A. Advancing consumer engagement: Supporting, developing and empowering youth leadership in cancer care. Eur J Cancer Care 2018; 27: e12958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Health Consumers Queensland . Consumer and Community Engagement Framework . 2017. [Accessed May 19, 2023]. Available from: https://www.hcq.org.au/wp‐content/uploads/2017/03/HCQ‐CCE‐Framework‐2017.pdf.

- 24. National Health and Medical Research Council . Consumer and community representatives in peer review for Targeted Calls for Research | NHMRC. [Accessed November 14, 2023]. Available from: https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/about‐us/consumer‐and‐community‐involvement/consumer‐and‐community‐representative‐involvement‐peer‐review‐process‐targeted‐calls‐research.

- 25. Medical Research Future Fund . Principles for consumer involvement in research funded by the Medical Research Future Fund. 2023. Available from: https://www.health.gov.au/committees‐and‐groups/medical‐research‐future‐fund‐consumer‐reference‐panel.

- 26. Richards DP, Birnie KA, Eubanks K, et al. Guidance on authorship with and acknowledgement of patient partners in patient‐oriented research. Res Involv Engagem 2020; 6: 38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. National Health and Medical Research Council . Authorship: A Guide Supporting the Australian Code for the Responsible Conduct of Research . National Health and Medical Research Council, Australian Research Council and Universities Australia, 2019.

- 28. International Committee of Medical Journal Editors . Defining the Role of Authors and Contributors. [Accessed November 14, 2023]. Available from: https://www.icmje.org/recommendations/browse/roles‐and‐responsibilities/defining‐the‐role‐of‐authors‐and‐contributors.html.

- 29. Bird M, Ouellette C, Whitmore C, et al. Preparing for patient partnership: A scoping review of patient partner engagement and evaluation in research. Health Expect 2020; 23: 523–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Health Consumers Queensland . Remuneration and Reimbursement of Consumers – Position Statement. 2015. [Accessed August 29, 2023]. Available from: https://www.hcq.org.au/wp‐content/uploads/2015/12/Consumer‐Remuneration‐Rates‐Dec‐2015.pdf.

- 31. Queensland Health . Consumer payment and re‐imbursement of expenses – Queensland Clinical Guidelines. 2019. [Accessed August 29, 2023]. Available from: https://www.health.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0016/143350/o‐consum‐fees.pdf.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed.