Abstract

Background and Objectives

Previously we demonstrated that 90% of infarcts in children with sickle cell anemia occur in the border zone regions of cerebral blood flow (CBF). We tested the hypothesis that adults with sickle cell disease (SCD) have silent cerebral infarcts (SCIs) in the border zone regions, with a secondary hypothesis that older age and traditional stroke risk factors would be associated with infarct occurrence in regions outside the border zones.

Methods

Adults with SCD 18–50 years of age were enrolled in a cross-sectional study at 2 centers and completed a 3T brain MRI. Participants with a history of overt stroke were excluded. Infarct masks were manually delineated on T2–fluid-attenuated inversion-recovery MRI and registered to the Montreal Neurological Institute 152 brain atlas to generate an infarct heatmap. Border zone regions between anterior, middle, and posterior cerebral arteries (ACA, MCA, and PCA) were quantified using the Digital 3D Brain MRI Arterial Territories Atlas, and logistic regression was applied to identify relationships between infarct distribution, demographics, and stroke risk factors.

Results

Of 113 participants with SCD (median age 26.1 years, interquartile range [IQR] 21.6–31.4 years, 51% male), 56 (49.6%) had SCIs. Participants had a median of 5.5 infarcts (IQR 3.2–13.8). Analysis of infarct distribution showed that 350 of 644 infarcts (54.3%) were in 4 border zones of CBF and 294 (45.6%) were in non–border zone territories. More than 90% of infarcts were in 3 regions: the non–border zone ACA and MCA territories and the ACA-MCA border zone. Logistic regression showed that older participants have an increased chance of infarcts in the MCA territory (odds ratio [OR] 1.08; 95% CI 1.03–1.13; p = 0.001) and a decreased chance of infarcts in the ACA-MCA border zone (OR 0.94; 95% CI 0.90–0.97; p < 0.001). The presence of at least 1 stroke risk factor did not predict SCI location in any model.

Discussion

When compared with children with SCD, in adults with SCD, older age is associated with expanded zones of tissue infarction that stretch beyond the traditional border zones of CBF, with more than 45% of infarcts in non–border zone regions.

Introduction

Children and adults with sickle cell disease (SCD) have a high prevalence of silent cerebral infarcts (SCIs). SCIs are associated with cognitive impairment and accumulate with age.1,2 Prior work has shown that SCIs in children occur most commonly in the deep white matter of the frontal and parietal lobes, within the border zones of cerebral artery blood flow. Furthermore, peak SCI density occurs in the region of lowest cerebral blood flow (CBF), suggesting a hemodynamic etiology.3 The border zone distribution of SCIs is present even in the absence of intracranial stenosis.

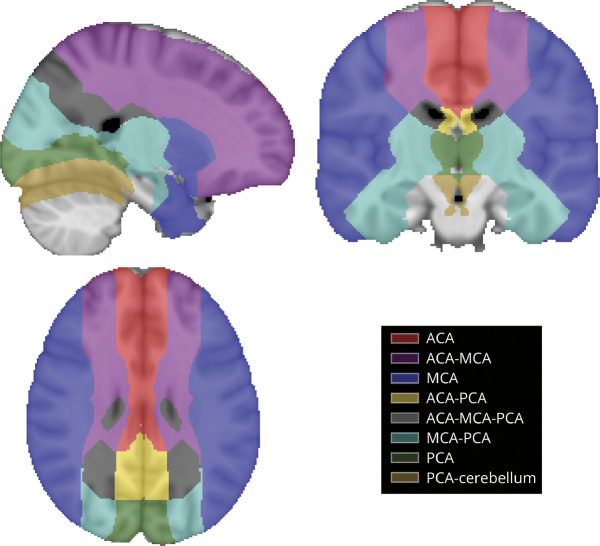

Cerebral infarct patterns have not been well characterized in adults with SCD. Yet, we hypothesize that adults may have a similar regional cerebral ischemic vulnerability to children with SCD due to anemic hypoxia and associated hematometabolic stress. Furthermore, adults may have additional vulnerability to stroke related to the accumulation of more traditional stroke risk factors outside of SCD or may develop stroke risk factors in the setting of SCD-related organ dysfunction. Recently, a 3D Brain MRI Arterial Territories Atlas defined the brain regions supplied by cerebral arteries,4 allowing a more refined analysis of infarct distribution and potential etiologies within specific arterial and border zone territories (Figure 1).

Figure 1. CBF Territories.

Visualization of the atlas of vascular territories and border zones of CBF used for this study.4 CBF = cerebral blood flow.

We aimed to expand the understanding of cerebral infarct patterns and stroke mechanisms in SCD using a large sample of adults with SCD. We tested the hypothesis that: (1) similar to children, adults with SCD have infarcts in the border zones between arterial blood flow territories, but that advanced age is associated with a wider spread of infarcts beyond the usual border zones and (2) traditional stroke risk factors (hypertension, diabetes, smoking, and chronic kidney disease) are associated with expanded regions of infarction beyond the border zones.

Methods

Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations, and Patient Consents

All participants provided written informed consent for this study, which was Institutional Review Board approved at Vanderbilt and Washington University Medical Centers. All eligible participants with SCD were approached and recruited sequentially from SCD clinics at 2 academic medical centers from September 2014 to December 2021 with MRI completion and cross-sectional data collection during this period. Inclusion criteria were as follows: age = 18–50 years, and SCD was defined as hemoglobin HbSS, HbSβ0 thalassemia, or HbSC. Exclusion criteria were as follows: history of overt stroke, contraindication to 3T MRI, major neurologic or psychiatric condition besides SCD, and major structural brain abnormality. Approximately 20% of those approached for study participation declined or initially agreed and then could not be reached to schedule a study visit. Another 5% initially agreed but failed MRI screening due to a contraindication such as metal in the body or claustrophobia.

Sequences

Each participant was imaged on a 3T MR scanner (Philips Achieva or Elition at one academic institution or Siemens Trevo, Trio, or Prisma at the other academic institution). A 3D T1-weighted magnetization‐prepared rapid gradient echo sequence (1.0 mm isotropic) was acquired for spatial referencing along with a 2D axial T2 fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) sequence (Philips: 1.0 × 1.1 × 3.0 mm Philips; Siemens: 1.0 × 0.9 × 3.0 mm).

Infarct Definition and Distribution Visualization

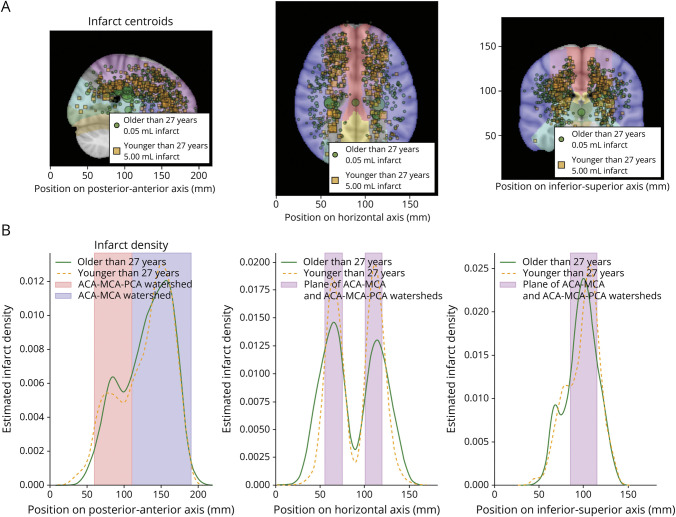

The FLAIR image was used to identify infarcts. Infarcts were manually delineated by an imaging analyst and board-certified vascular neurologist and confirmed by a board-certified neuroradiologist. Lesions at least 3 mm in size on axial FLAIR without clinical symptoms or signs were defined as SCI and were traced to create an infarct mask for each participant. Lesion position was determined using the centroid of the lesion (i.e., the average coordinate value of all voxels in a lesion), and the infarct was assigned to the arterial territory or border zone that the centroid fell within. Infarct distribution, overlap, and size were plotted for participants with SCD (Figure 2). To visualize distribution, the center position of each infarct was plotted as a projection onto the sagittal, axial, and coronal planes of the Montreal Neurological Institute 152 brain atlas; each point was scaled by the size of the infarct. Infarct positions for participants over and under the mean SCD age (27.0 years) were plotted with separate colors. These 2D infarct positions were then further projected onto a 1D axis, posterior-anterior, horizontal (i.e., anatomical right-left), and inferior-superior, and the probability density of infarcts as a function of position on this axis along each visualized using a kernel density estimation with a bandwidth of 10 mm. Plotting in this way allowed visualization of infarct distribution without infarct size as a confounder.

Figure 2. Silent Cerebral Infarct Distributions in Individuals With Sickle Cell Disease, Separated by Age (Younger or Older Than 27 Years).

Row A shows infarct distributions and relative infarct sizes as projected onto a plane, separately for younger individuals with SCD (younger than 27 years; orange squares) and older individuals with sickle cell disease (older than 27 years of age; green circles). Data are scaled by infarct volume. There was no significant difference in lesion size by age or location. Row B shows kernel density estimate of infarcts along single axes corresponding to the corresponding panel above in row A. The border zones (watersheds) of CBF, the ACA-MCA, and ACA-MCA-PCA triple border zone have high numbers of infarcts. ACA = anterior cerebral artery; CBF = cerebral blood flow; MCA = middle cerebral artery; PCA = posterior cerebral artery; SCD = sickle cell disease.

In addition, infarct maps within each age group (under vs over age = 27 years) were summed and plotted as heatmaps (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Infarct Heatmaps.

Axial and coronal heatmaps showing the sum of all infarct maps for all participants younger (left) or older (right) than 27 years, the mean age of study participants. Color intensities are normalized within each group. The infarct distribution in the older than 27 years group shows marked lateral spread compared with the younger than 27 years group, suggesting that the zones of susceptibility to silent cerebral infarction in SCD expand with age. SCD = sickle cell disease.

Variables were gathered from the medical record and through participant interviews including age, sex, hemoglobin phenotype, and traditional stroke risk factors (hypertension, diabetes, smoking, chronic kidney disease, and diabetes). For both study populations, laboratory studies including venous Hb, quantification of the percentage of HbS, and vital signs including oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry (SpO2) and systolic blood pressure were obtained before the MRI and pre transfusion in those receiving transfusions.

Descriptive Analysis

Demographic and clinical characteristics were summarized with the mean and standard deviation (normal data) or median and interquartile range (IQR) (non-normal data) for continuous variables and count and percent for categorical variables. Differences in continuous variables were assessed with independent sample t tests or Mann-Whitney U tests for non-normally distributed data. Categorical variables were evaluated using a χ2 test or Fisher exact test for small cell counts. All tests were two-sided.

With an overall goal of assessing whether infarct distribution is affected by age and stroke risk factors in SCD, we used logistic regression to calculate the odds of a given infarct occurring in a particular border zone or a vascular territory vs an infarct in any other area of the brain. We constructed 1 model each for the blood flow territories or border zones with the most infarcts (anterior cerebral artery [ACA], middle cerebral artery [MCA], and ACA-MCA). For each region of interest, the model used a binary variable indicating whether an infarct was within that region, or not, as the dependent variable, with age, sex, and a binary variable representing the presence of at least 1 traditional stroke risk factor (hypertension, diabetes, smoking, and chronic kidney disease) as covariates.

A participant could be represented multiple times in the logistic regression model based on the number of their infarcts. To adjust for this, we clustered by participant, using robust clustered standard errors based on the Huber-White sandwich estimator. The standard errors allowed for interperson correlation rather than requiring independence of the observations. A p value of 0.05 was used to assess statistical significance. Statistical models were constructed using Stata 18.0.

Data Availability

Anonymized data not published within this article and code used for its statistical analysis will be made available by request from any qualified investigator with appropriate approvals for at least 5 years from the date of publication of this article.

Results

A total of 145 participants with SCD were enrolled with high-quality MRI of the brain, and 5 participants did not have an adequate FLAIR sequence for infarct assessment; participants with a diagnosis of overt stroke based on history, neurologic examination, and neuroimaging (N = 27) were excluded for a final sample of 113 participants (median age 26.1 years, IQR 21.6–31.4 years and mean age = 27.3 ± 6.3 years, 51% male) including 56 (49.6%) with at least 1 SCI, see eFigure 1 for flowchart. In total, 644 infarcts were identified and used for calculations. Participant demographic information is summarized in Table 1. There was no missing data on any of these clinical variables. The number of infarcts for a participant ranged from 1 to 72. The median number of infarcts per participant was 5.5 (IQR 3.2–13.8).

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Baseline Information for Participants With SCD With and Without Silent Cerebral Infarcts (N = 113)

| Variable | No infarcts (n = 57) | Infarcts present (n = 56) | p Valuea |

| Age at MRI, y, median (IQR) | 24.6 (20.6–29.5) | 28.0 (23.1–32.9) | 0.024 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 31 (54.4) | 27 (48.2) | 0.64 |

| Hemoglobin phenotype, n (%) | 0.99b | ||

| SS and Sβthal0 | 53 (93.0) | 52 (92.9) | |

| SC, other | 4 (7.0) | 4 (7.1) | |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL, mean (SD) | 9.4 (1.5) | 9.0 (1.7) | 0.23 |

| HbS%, median (IQR) | 75.1 (58.6–81.3) | 76.6 (51.2–83.7) | 0.86 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 23.8 (4.5) | 23.5 (4.6) | 0.72 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg, mean (SD) | 116.2 (12.2) | 116.8 (13.9) | 0.81 |

| Type 1 diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.8) | 0.50# |

| Hypercholesterolemia, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | NA |

| Chronic kidney disease, n (%) | 3 (5.3) | 3 (5.4) | 1.00# |

| Smoking currently, n (%) | 7 (12.3) | 8 (14.3) | 0.97 |

| Antihypertensive medication, n (%) | 5 (8.8) | 3 (5.4) | 0.72 |

| At least 1 traditional stroke risk factor, n (%) | 11 (19.3) | 13 (23.2) | 0.611 |

| Infarct volume, mL, median (IQR), (n = 56) | NA | 0.52 (0.22–1.85) | NA |

| Intracranial stenosis >50%, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (10.7) | 0.013 |

Abbreviations: IQR = interquartile range; NA = not applicable.

Chi-square test for counts, t test for mean values, and Mann-Whitney test for medians.

Fisher exact test.

Infarct distribution by zone and territory is summarized in Table 2. Notably, 54.3% (350 of 644 infarcts) were in 4 border zones of CBF, and 45.6% (294 of 644) were in non–border zone territories. Infarcts had a predilection for the anterior circulation because the ACA and MCA territories and the ACA-MCA border zone together accounted for 90% of infarcts.

Table 2.

Number and Percentage of Infarcts by Blood Flow Territory and Border Zone (n = 56 Participants)

| Region or territory | Number of infarcts | Percentage |

| ACA | 92 | 14.3 |

| ACA-MCA | 302 | 46.9 |

| MCA | 198 | 30.7 |

| ACA-PCA | 2 | 0.3 |

| ACA-MCA-PCA | 27 | 4.2 |

| MCA-PCA | 19 | 3.0 |

| PCA | 4 | 0.6 |

| PCA-cerebellum | 0 | 0.0 |

| Total | 644 | 100 |

Abbreviations: ACA = anterior cerebral artery, MCA = middle cerebral artery; PCA = posterior cerebral artery.

Visualization of Infarct Distribution in SCD

Representations of infarct distributions in SCD are shown in Figure 2. Row A shows the distribution of infarcts on each anatomical plane, while row B shows the distribution of those infarcts as a probability density function corresponding to a single 1D axis that aligns to the x-axis of the anatomical plane above it. The data in rows A and B are plotted separately for participants older and younger than the mean age in this cohort (27.0 years). A noticeable change in distributions between the older and younger cohorts is observable in the axial and coronal planes, where the infarcts in the older group seem to be distributed across a wider lateral region than in the younger group. The density function in the horizontal (right-left) axis (row B column 2) further supports this, showing a tight peak in the younger group that widens in the older group, indicating that the infarcts in the older group are distributed more broadly. Peaks in infarct distribution coincide with border zones on all axes. On the posterior-anterior axis, the largest peak occurs in the ACA-MCA border zone, while a smaller peak occurs at the ACA-MCA-PCA border zone.

We further visualized the infarct distribution by creating infarct density maps for each age group (participants older or younger than 27 years). These maps were created by summing all infarct maps for each group on a voxel-wise basis; greater intensities of a voxel indicate the greater prevalence of infarction in that voxel. This is shown in Figure 3. Again, infarcts are noticeably restricted to the ACA-MCA border zone in the younger group but expand laterally in the older group. Additional visualization of infarct number and age is in eFigure 2.

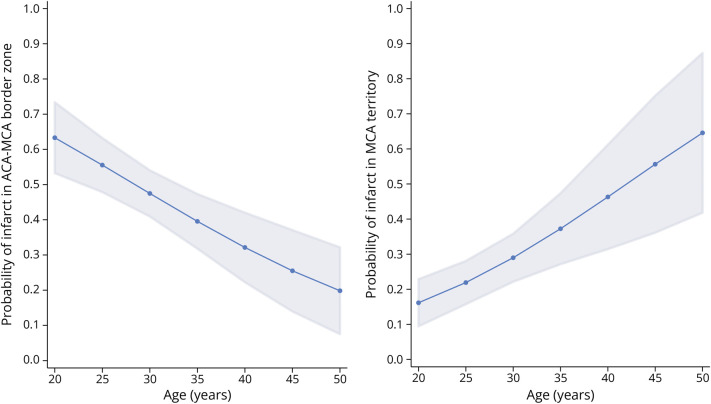

Because 90% of infarcts were found in the 3 regions, the ACA territory, MCA territory and ACA-MCA border zone, the other blood flow regions and border zones were not included in the regression models. The logistic regression model for the presence of an infarct in the ACA territory found no effect for age (odds ratio [OR] 1.01; p = 0.537) while controlling for risk factors (Table 3). The logistic regression model for the presence of an infarct in the MCA territory found an association with age (OR = 1.08; 95% CI 1.03–1.13; p = 0.001), such that older participants have an increased chance of an infarct in the MCA territory, with each additional year of age increasing the odds by 1.08. Figure 4 displays the predicted probability from the model of an infarct occurring in the MCA territory by age. The logistic regression model for the presence of an infarct in the ACA-MCA border zone found an association with age (OR = 0.94; 95% CI 0.90–0.97; p < 0.001), such that older participants have a decreased chance of an infarct in the ACA-MCA border zone, with each additional year of age decreasing the odds by 0.94. The presence of at least 1 risk factor was not significant in any model.

Table 3.

Logistic Regression Models for Infarct Location in the ACA or MCA Territories or the ACA-MCA Border Zonea

| Territory or border zone | Variable | Odds ratio | 95% CI | p Value |

| ACA | Age | 1.01 | 0.97–1.06 | 0.537 |

| Sex, male | 0.91 | 0.42–1.97 | 0.814 | |

| At least one risk factor | 1.62 | 0.75–3.50 | 0.223 | |

| MCA | Age | 1.08 | 1.03–1.13 | 0.001 |

| Sex, male | 0.76 | 0.39–1.46 | 0.410 | |

| At least one risk factor | 1.71 | 0.74–3.95 | 0.210 | |

| ACA-MCA | Age | 0.94 | 0.90–0.97 | <0.001 |

| Sex, male | 1.38 | 0.86–2.24 | 0.184 | |

| At least one risk factor | 0.62 | 0.33–1.14 | 0.122 |

N = 56 participants with at least 1 infarct (n = 644 infarcts).

The reference location for each analysis is all other vascular territories besides the territory indicated.

Figure 4. Probability of Cerebral Infarction by Age.

Logistic regression model predictions of the probability of an infarct in the anterior cerebral artery-middle cerebral artery (ACA-MCA) border zone vs all other territories by age, controlling for sex and the presence of at least 1 stroke risk factor (left panel) and the MCA territory vs all other territories by age, controlling for sex and the presence of at least 1 stroke risk factor (right panel). Shading represents 95% CIs.

Discussion

SCI distribution patterns differ in adults with SCD compared with children with SCD. In adults, only 54% of infarcts were in the border zones of CBF compared with 90% for children with SCD.3

We also found that increasing age was associated with increased odds of infarct location in the MCA blood flow territory and a decreased likelihood of an infarct located in the ACA-MCA border zone. There are 2 possible explanations for this finding. One possibility is that CBF decreases with age, thus broadening the border zone (area of low blood flow) between territories and bringing more brain tissue under a state of tenuous perfusion, including tissue within the deep MCA territory. However, recent work in a single-center series has suggested that while CBF is known to decrease with age in healthy controls,5 CBF increases with age in many individuals with SCD in cross-sectional data from children and young adults aged 6–40 years.6 This makes the prior explanation less likely, so we suggest a second possibility: that localized tissue susceptibility, possibly due to accelerated blood transit through the capillary bed as described by Juttukonda et al.7 and others,8 is an important cause of SCI in SCD and that tissue integrity is increasingly compromised with time. Even with compensatory hyperemia, this expanding swath of compromised tissue may result in increased proportions of infarction outside previously defined border zones. Territorial or wedge-like infarcts were not seen in our analysis because overt strokes have been purposely excluded.

Surprisingly, the presence of stroke risk factors had no association with the odds of infarct locations. Our results demonstrate that the distribution of SCI widens with age. We did not prove our hypothesis that infarcts in non–border zone regions were due to the presence of traditional stroke risk factors (hypertension, diabetes, smoking, and chronic kidney disease). Furthermore, stroke etiologies beyond small vessel disease, such as thromboembolic or cardiac source of small emboli, could play a role in these wider distributions and may also be related to traditional stroke risk factors. One strong possibility for this lack of relationship between traditional stroke risk factors and infarct expansion could be the relatively low proportion of patients who had traditional stroke risk factors in this cohort. For example, less than 10% of our cohort was taking an antihypertensive medication, 1 patient carried a diagnosis of diabetes, none carried a diagnosis of hypercholesterolemia, and overall, 21% had 1 or more of these non–SCD-related risk factors.

The distribution of border zone infarcts with the majority in the ACA-MCA rather than the MCA-PCA or ACA-PCA border zones is interesting and may simply reflect that 72% of CBF is in the anterior circulation while only 28% is in the posterior circulation,9 so in the presence of anemia, this region of the brain is most at risk of infarcts. However, the proportion of infarcts is much lower in the posterior circulation, which suggests an additional, yet unknown explanation. Although intracranial stenosis is more common in the anterior than the posterior circulation, in this cohort, only 6 participants had intracranial stenosis. The “triple border zone” of the ACA-MCA-PCA seems to be an area of increased infarct density on the heatmaps (Figures 2 and 3) despite being a small area within the brain. While not commonly discussed, this triple border zone could be a unique area of vulnerability based on tenuous CBF.

SCIs were present in nearly 50% of our cohort of adults with SCD, and 37% of children with SCD have SCI by 14 years of age.10 There seems to be no plateau with age with SCI accumulating over time.2 SCIs do not present with focal neurologic deficits but are associated with measurable deficits in multiple cognitive domains in children.1,11 Further work is needed to understand the cognitive impact of SCI in adults with SCD12,13 and to prevent SCIs in those older than 18 years. In children with SCI, monthly blood transfusions have been shown to reduce the risk of new SCI.14 However, similar work studying transfusions for secondary stroke prevention has not been conducted in adults. For some patients, stem cell transplant or gene therapy are curative options; work is ongoing to study the impact of these therapies on the brain.15-17

The clinical implications of the broader infarct distribution patterns at older ages in SCD should be further studied. Whether consistent use of disease-modifying therapies for SCD beginning at a younger age and across the life span will reduce the number of infarcts and spreading of infarcts is an important question, with implications for overall brain health. SCD has recently been described as a premature aging syndrome.18

Strengths of this work include a relatively large sample of adults with SCD with high-resolution MRI from 2 centers. Limitations of this study include our simple definition of cerebrovascular border zones, which states that border zones are any vascular regions within 10 mm of another region. This definition does not fully capture some subtle geometric aspects of known border zones and potential anatomical variations in border zone regions but does provide a consistent metric for quantifying vascular outcomes while also creating a reasonable heuristic approximation of known border zone geometry. The number of older adults with SCD is also a study limitation. Adults with SCD have an average life expectancy of 42–48 years,19-21 thus our cohort includes a relatively small number of participants aged 40 years and older (6.2%; 7/113). Finally, this work was conducted at 2 academic medical centers with comprehensive SCD programs. This could limit the generalizability of our results, although most individuals with SCD in high-income settings are followed up in similar programs. In a low-income setting, patients with SCD may have reduced access to disease-modifying therapies such as transfusion and hydroxyurea22 and thus could experience a higher rate of cerebrovascular events at a younger age. We expect that our main finding—that brain tissue vulnerability expands with age in SCD—will generalize to the broader population with SCD. However, the rate at which this area of vulnerability expands may vary.

Silent cerebral infarcts are known to occur primarily in the ACA-MCA border zone (regions of lowest CBF at the edges of vascular territories) in children with SCD. This work shows that in adults with SCD, older age is associated with expanded zones of tissue infarction that stretch beyond the traditional border zone. These findings suggest that aging may cause expanded areas of tissue vulnerability within the brains of adults with SCD, possibly due to microvascular compromise.

Glossary

- ACA

anterior cerebral artery

- CBF

cerebral blood flow

- FLAIR

fluid-attenuated inversion recovery

- IQR

interquartile range

- MCA

middle cerebral artery

- OR

odds ratio

- PCA

posterior cerebral artery

- SCD

sickle cell disease

- SCI

silent cerebral infarct

Appendix. Authors

| Name | Location | Contribution |

| R. Sky Jones, BS | Pediatrics, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN | Drafting/revision of the article for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data; and analysis or interpretation of data |

| Andria L. Ford, MD | Neurology, Washington University, St. Louis, MO | Drafting/revision of the article for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data; and study concept or design |

| Manus J. Donahue, PhD | Neurology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN | Drafting/revision of the article for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data; and analysis or interpretation of data |

| Slim Fellah, PhD | Neurology, Washington University, St. Louis, MO | Drafting/revision of the article for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data |

| L. Taylor Davis, MD | Radiology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN | Drafting/revision of the article for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data |

| Sumit Pruthi, MBBS | Radiology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN | Drafting/revision of the article for content, including medical writing for content |

| Charu Balamurugan, BS | Pediatrics, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN | Drafting/revision of the article for content, including medical writing for content |

| Rachel Cohen, BS | Neurology, Washington University, St. Louis, MO | Major role in the acquisition of data |

| Samantha Davis, MS | Pediatrics, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN | Drafting/revision of the article for content, including medical writing for content |

| Michael R. Debaun, MD, MPH | Vanderbilt-Meharry Center of Excellence in Sickle Cell Disease, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN | Drafting/revision of the article for content, including medical writing for content |

| Adetola A. Kassim, MD | Medicine, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN | Drafting/revision of the article for content, including medical writing for content |

| Mark Rodeghier, PhD | Rodeghier Consulting, Chicago, IL | Drafting/revision of the article for content, including medical writing for content; analysis or interpretation of data |

| Lori C. Jordan, MD, PhD | Pediatrics, Neurology and Radiology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN | Drafting/revision of the article for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data; study concept or design; and analysis or interpretation of data |

Footnotes

Editorial, page e209319

Study Funding

This research was supported by the NIH, R01H155207 (LCJ) K24-HL147017 (LCJ) R01HL129241 (ALF). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Disclosure

R.S. Jones reports no disclosures relevant to the manuscript; A.L. Ford reports no disclosures relevant to the manuscript; M.J. Donahue is a paid consultant for Global Blood Therapeutics, receives advisory board, receives research-related support from Philips North America, and is the CEO of Biosight LLC, which provides health care technology consulting services. These agreements have been approved by Vanderbilt University Medical Center in accordance with its conflict of interest policy; S. Fellah reports no disclosures relevant to the manuscript; L.T. Davis reports no disclosures relevant to the manuscript; S. Pruthi reports no disclosures relevant to the manuscript; C. Balamurugan reports no disclosures relevant to the manuscript; R. Cohen reports no disclosures relevant to the manuscript; S. Davis reports no disclosures relevant to the manuscript; M.R. DeBaun and his institution sponsored 2 externally funded research investigator–initiated projects. Global Blood Therapeutics (GBT) provided funding for the cost of the clinical studies. GBT was not a cosponsor of either study. Dr. DeBaun did not receive any compensation for the conduct of these 2 investigator-initiated observational studies. Dr. DeBaun was member of the Global Blood Therapeutics advisory board for a proposed randomized controlled trial for which he receives compensation. Dr. DeBaun is on the steering committee for a Novartis-sponsored phase 2 trial to prevent priapism in men. Dr. DeBaun was a medical advisor in developing the CTX001 Early Economic Model. Dr. DeBaun provided medical input on the economic model as part of an expert reference group for the Vertex/CRISPR CTX001 Early Economic Model in 2020. Dr. DeBaun consulted for the Forma Pharmaceutical company about sickle cell disease in 2021 and 2022; A.A. Kassim reports no disclosures relevant to the manuscript; M. Rodeghier reports no disclosures relevant to the manuscript; L.C. Jordan receives minor royalties from UpToDate, an evidence-based clinical information resource, for chapters she has written on stroke in sickle cell disease. Go to Neurology.org/N for full disclosures.

References

- 1.King AA, Strouse JJ, Rodeghier MJ, et al. Parent education and biologic factors influence on cognition in sickle cell anemia. Am J Hematol. 2014;89(2):162-167. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kassim AA, Pruthi S, Day M, et al. Silent cerebral infarcts and cerebral aneurysms are prevalent in adults with sickle cell anemia. Blood. 2016;127(16):2038-2040. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-01-694562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ford AL, Ragan DK, Fellah S, et al. Silent infarcts in sickle cell disease occur in the border zone region and are associated with low cerebral blood flow. Blood. 2018;132(16):1714-1723. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-04-841247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu CF, Hsu J, Xu X, et al. Digital 3D brain MRI arterial territories atlas. Sci Data. 2023;10(1):74. doi: 10.1038/s41597-022-01923-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Han H, Lin Z, Soldan A, et al. Longitudinal changes in global cerebral blood flow in cognitively normal older adults: a phase-contrast MRI study. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2022;56(5):1538-1545. doi: 10.1002/jmri.28133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Waddle SLJL, Juttukonda MR, Lee CA, Patel NJ, Donahue MJ. Evolution of Cerebral Hemodynamics and Metabolism Across the Early Lifespan in Patients With Sickle Cell Disease. Abstract #294. International Society of Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Man (ISMRM); 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Juttukonda MR, Donahue MJ, Waddle SL, et al. Reduced oxygen extraction efficiency in sickle cell anemia patients with evidence of cerebral capillary shunting. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2021;41(3):546-560. doi: 10.1177/0271678X20913123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Afzali-Hashemi L, Vaclavu L, Wood JC, et al. Assessment of functional shunting in patients with sickle cell disease. Haematologica. 2022;107(11):2708-2719. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2021.280183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zarrinkoob L, Ambarki K, Wahlin A, Birgander R, Eklund A, Malm J. Blood flow distribution in cerebral arteries. J Cereb Blood flow Metab. 2015;35(4):648-654. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2014.241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bernaudin F, Verlhac S, Arnaud C, et al. Impact of early transcranial Doppler screening and intensive therapy on cerebral vasculopathy outcome in a newborn sickle cell anemia cohort. Blood. 2011;117(4):1130-1140. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-06-293514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prussien KV, Jordan LC, DeBaun MR, Compas BE. Cognitive function in sickle cell disease across domains, cerebral infarct status, and the lifespan: a meta-analysis. J Pediatr Psychol. 2019;44(8):948-958. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsz031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prussien KV, Siciliano RE, Ciriegio AE, et al. Correlates of cognitive function in sickle cell disease: a meta-analysis. J Pediatr Psychol. 2020;45(2):145-155. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsz100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vichinsky EP, Neumayr LD, Gold JI, et al. Neuropsychological dysfunction and neuroimaging abnormalities in neurologically intact adults with sickle cell anemia. JAMA. 2010;303(18):1823-1831. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeBaun MR, Gordon M, McKinstry RC, et al. Controlled trial of transfusions for silent cerebral infarcts in sickle cell anemia. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(8):699-710. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1401731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carpenter JL, Nickel RS, Webb J, et al. Low rates of cerebral infarction after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in patients with sickle cell disease at high risk for stroke. Transpl Cell Ther. 2021;27(12):1018.e1-1018.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.jtct.2021.08.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aumann M, Richerson WT, Song AK, et al. Cerebral hemodynamic changes after haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplant in adults with sickle cell disease. Blood Adv. 2024;8(3):608-619. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2023010717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Afzali-Hashemi L, Dovern E, Baas KPA, et al. Cerebral hemodynamics and oxygenation in adult patients with sickle cell disease after stem cell transplantation. Am J Hematol. 2024;99(2):163-171. doi: 10.1002/ajh.27135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Idris IM, Botchwey EA, Hyacinth HI. Sickle cell disease as an accelerated aging syndrome. Exp Biol Med. 2022;247(4):368-374. doi: 10.1177/15353702211068522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Platt OS, Brambilla DJ, Rosse WF, et al. Mortality in sickle cell disease. Life expectancy and risk factors for early death. N Engl J Med. 1994;330(23):1639-1644. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199406093302303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Payne AB, Mehal JM, Chapman C, et al. Trends in sickle cell disease-related mortality in the United States, 1979 to 2017. Ann Emerg Med. 2020;76(3S):S28-S36. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2020.08.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DeBaun MR, Ghafuri DL, Rodeghier M, et al. Decreased median survival of adults with sickle cell disease after adjusting for left truncation bias: a pooled analysis. Blood. 2019;133(6):615-617. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-10-880575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arji EE, Eze UJ, Ezenwaka GO, Kennedy N. Evidence-based interventions for reducing sickle cell disease-associated morbidity and mortality in sub-Saharan Africa: a scoping review. SAGE Open Med. 2023;11:20503121231197866. doi: 10.1177/20503121231197866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized data not published within this article and code used for its statistical analysis will be made available by request from any qualified investigator with appropriate approvals for at least 5 years from the date of publication of this article.