Abstract

Background

Compositional and structural features of retrieved clots by thrombectomy can provide insight into improving the endovascular treatment of ischemic stroke. Currently, histological analysis is limited to quantification of compositions and qualitative description of the clot structure. We hypothesized that heterogeneous clots would be prone to poorer recanalization rates and performed a quantitative analysis to test this hypothesis.

Methods

We collected and did histology on clots retrieved by mechanical thrombectomy from 157 stroke cases (107 achieved first-pass effect [FPE] and 50 did not). Using an in-house algorithm, the scanned images were divided into grids (with sizes of 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5, and 0.6 mm) and the extent of non-uniformity of RBC distribution was computed using the proposed spatial heterogeneity index (SHI). Finally, we validated the clinical significance of clot heterogeneity using the Mann–Whitney test and an artificial neural network (ANN) model.

Results

For cases with FPE, SHI values were smaller (0.033 vs 0.039 for grid size of 0.3 mm, p = 0.028) compared to those without. In comparison, the clot composition was not statistically different between those two groups. From the ANN model, clot heterogeneity was the most important factor, followed by fibrin content, thrombectomy techniques, RBC content, clot area, platelet content, etiology, and admission of IV-tPA. No statistical difference of clot heterogeneity was found for different etiologies, thrombectomy techniques, and IV-tPA administration.

Conclusion

Clot heterogeneity can affect the clot response to thrombectomy devices and is associated with lower FPE. SHI can be a useful metric to quantify clot heterogeneity.

INTRODUCTION

Using thrombectomy devices to retrieve clots from patients has become standard of care for large vessel occlusion (LVO) stroke and created opportunities to analyze the retrieved clots by various techniques including histology,1 mechanical testing,2,3 and imaging.4 These tools have enabled better understanding of clot mechanics, biology and pathophysiology in order to optimize stroke management. Among all the techniques, histology is the most widely used. However, most histology studies have been limited to reporting the bulk percentages of different clot components and the description of the clot structure, which is known to be quite heterogeneous and the data on clot heterogeneity has been subjective and qualitative.5,6 We hypothesized that the extent of clot heterogeneity could affect the clot response to thrombectomy devices. This is based off the idea that heterogeneous clots would be more prone to fragmentation during the thrombectomy procedure due to lack of homogeneity in the structures binding the clot together. In this study, we developed an algorithm to objectively quantify the clot heterogeneity. We then evaluated the association between clot heterogeneity and first-pass effect (FPE) and compared to that of clot compositions and procedure variables.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Clot collection and histology

Clots were collected through the STRIP registry (Stroke Thromboembolism Registry of Imaging and Pathology), a multi-center study analyzing the histopathological and imaging characteristics of clots retrieved by thrombectomy from patients with acute ischemic stroke.1 Following IRB approval with granted waiver of consent, clots retrieved during thrombectomy from patients over 18 years of age were collected, formalin fixed and sent to our center for histology. Procedural details, such as administration of tPA, techniques of thrombectomy, and number of thrombectomy device-passes were also collected. Cases with complete recanalization (TICI 2c/3) were included in the analysis and we assumed such clots to best match the composition and heterogeneity of in-situ clots. Cases with incomplete recanalization (TICI 2b or less) were excluded as the analysis would be limited to the retrievable parts of the clot and the results on composition and heterogeneity would not represent that of in-situ clots. Cases with occlusion in distal arteries, in the ICA, in the posterior circulation, and in multiple locations were excluded. Clots which have been fixed in formalin for over 30 days were also excluded as the different components couldn’t be clearly identified using the image segmentation method. The clot samples were then embedded in paraffin, sectioned to 3 μm, and stained with Martius Scarlett Blue. In cases where multiple fragments were retrieved from one pass, all the fragments were sectioned and stained on a single slide. All the slides were scanned by a digital scanner (MoticEasyScan) at 20x magnification (Fig. 1A). Images were exported in *.jp2 format for heterogeneity quantification. Clot compositions and area were also analyzed by Orbit and ImageJ,7 respectively.

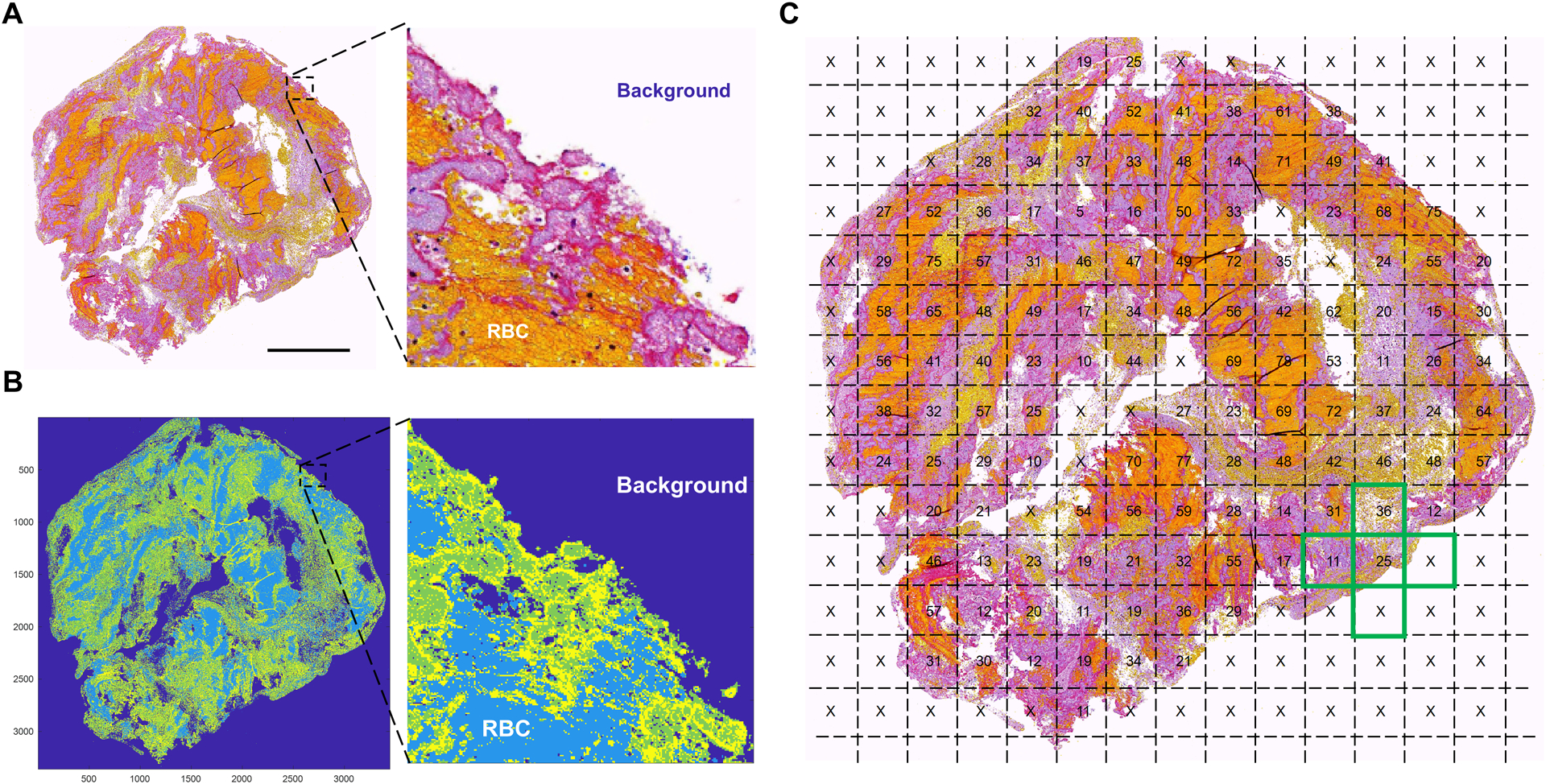

Figure 1. Quantification of clot spatial heterogeneity index.

First, the scanned images of stained clot slides (A) were segmented by K-means clustering and divided into different regions and the regions of RBC and background were labelled (B). The image was then divided into uniform grids and the percentages of RBCs in each grid were calculated and used to calculate the spatial heterogeneity index (C).

Heterogeneity quantification

Clot heterogeneity was quantified by an imaging analysis algorithm implemented in a mathematical software (Matlab 2020a). Similar algorithms have been used to quantify the spatial heterogeneity of thin sections of carbonate rock cores.8 First, the images were segmented by K-means clustering to divide the pixels into different regions. Then, under the guidance of an experienced (>20 years) pathologist (D.D.), the RBC and background regions were identified and labeled (Fig. 1B). The image was then divided into square interrogation grids with length h. The RBC contents (r) within each interrogation grid were then calculated (percentages in Fig. 1C) using the following equation:

| (1) |

where LR is the number of pixels with the label of RBC, H is the pixel count along the grid length h, and LB is the number of pixels with the label of background. The spatial heterogeneity index (SHI), defined by the averaged variation of RBC content between an interrogation grid and its neighboring grids, was calculated using the following equation:

| (2) |

where ri0, ri1, ri2, ri3, ri4 are the percentage of RBC (numbers in Fig. 1C) within, above, beneath, left to, and right to the interrogation grid i, respectively. N is the total number of grids with background occupying less than 50% of the area; grids with over 50% of background (“x” marks in Fig. 1C) were excluded from the heterogeneity quantification. RBC content was selected to compute the SHI value since RBC-rich regions are soft and fragile and are associated with iatrogenic distal embolization during thrombectomy.3 A homogeneous clot, whether RBC-, fibrin-, or platelets-rich, will have an SHI value of zero. In comparison, a heterogeneous clot with more RBC-rich region intersecting with fibrin network or platelet aggregates, will have a higher SHI value. For interrogation grids at the clot boundary (for example, the green cross in Fig. 1C), some of the neighboring grids were considered background (“x” marks). Such neighboring grids were assumed to have the identical RBC content compared to the center interrogation grid. As a result, the contribution of heterogeneity from grids at the clot boundary was lower than those at the clot interior. To study the effect of grid size on heterogeneity quantification, five grid sizes (0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5, and 0.6 mm) were used to compute the SHI spectrum. The upper bound of the size range (0.6 mm) was selected so that the smallest clot fragments (about 1.2 mm × 1.2 mm) had a minimum grid number of 4.

To determine which factor is associated with higher FPE rate, an exploratory two-layer multilayer perceptron artificial neural network (ANN) model with a back propagation algorithm was constructed. The ANN model worked like a logistic regression model to take multiple attributes of a subject as the input and predict the category it belongs to. Different than logistic regression, the ANN model has additional hidden layers to deal with more complex non-linear classification problems. The ANN model worked by passing data/signals through a series of nodes/neurons to categorize a subject (in this case, FPE or non-FPE) using the input attributes of the subject (in this case, SHI, clot composition, clot size, etc.). Within each neuron, the inputs were linearly combined with different weights and bias and then the resulting value was mapped to the range of 0 to 1, −1 to 1, or others through an activation function.9 The activation function was used to add non-linearity to the model as most real-world data is nonlinear. The output of this neuron was then passed to the next neuron until the end of the network. The final output would be the category the subject classified to. The most-used classification method, logistic regression, can be deemed as an ANN model with just one neuron and the final output is the probability of falling into the specified category. While the logistic regression is a linear model, the ANN model used in this study is more suitable to deal with this complex non-linear problem. In the exploratory ANN model, data were randomly assigned to batch training sample (70%) and test sample (30%). Sigmoid activation function was used in the hidden and output layers. Each hidden layer had 50 units. Scaled conjugate gradient was used for the optimization algorithm. The initial Lambda was 5e-7, initial Sigma was 5e-5, and the interval offset was ±0.5. Rescaling of covariates was performed with the standardized mode. To construct ANN, we used continuous variables for covariates including SHI, RBC content, fibrin content, platelet content, and clot area. For categorical variables including tPA administration, thrombectomy techniques, and stroke etiology, they were coded into dichotomous variables (“0” and “1”) as required to process by the ANN algorithm.

Statistical Analysis

To compare the SHI values, compositions, size, and number of fragments for clots between different groups, the Shapiro–Wilk test was carried out to check for normality, and then the t test was used for normally distributed data and the Mann–Whitney test was used for non-normally distributed data. Correlations between SHI values and clot compositions, size, and number of fragments were calculated using the Pearson’s linear correlation coefficient. Statistical significance was indicated by p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Heterogeneity distribution

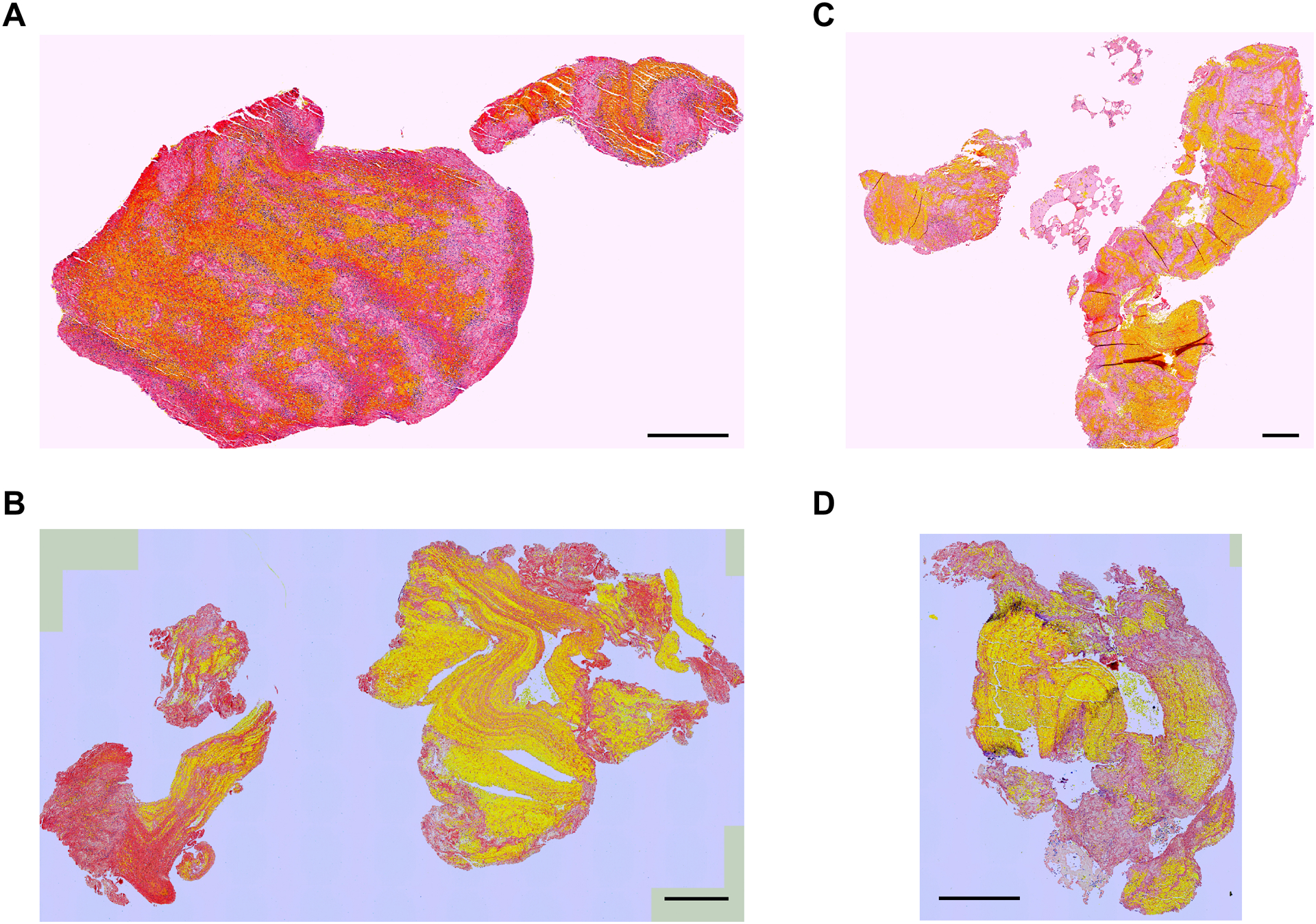

Clots retrieved from 157 (107 with FPE and 50 with non-FPE) LVO cases were analyzed. This cohort of clots had 47.0% (SD 19.8%) RBC, 29.7% (SD 15.8%) fibrin, and 19.9% (SD 16.0%) platelets. Cases in the non-FPE group required 2.79 (SD 1.27) device-passes to achieve complete recanalization. Clot SHI values had a large variance and were dependent on the grid size. In detail, this cohort of clots had SHI of 0.0451 (SD 0.0205), 0.0394 (SD 0.0188), 0.0346 (SD 0.0182), 0.0305 (SD 0.0177), 0.0258 (SD 0.0159) for the grid size of 0.2 mm, 0.3 mm, 0.4 mm, 0.5 mm, and 0.6 mm, respectively. Clots with similar RBC content can have a range of SHI values depending on the level of heterogeneity (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Examples of clots with similar RBC percentages but different SHI values: 37% RBC and SHI = 0.02 (A), 44% RBC and SHI = 0.03 (B), 44% RBC and SHI = 0.04 (C), 39% RBC and SHI = 0.05 (D).

Scale bar = 0.5 mm.

Effect of clot heterogeneity on first pass effect

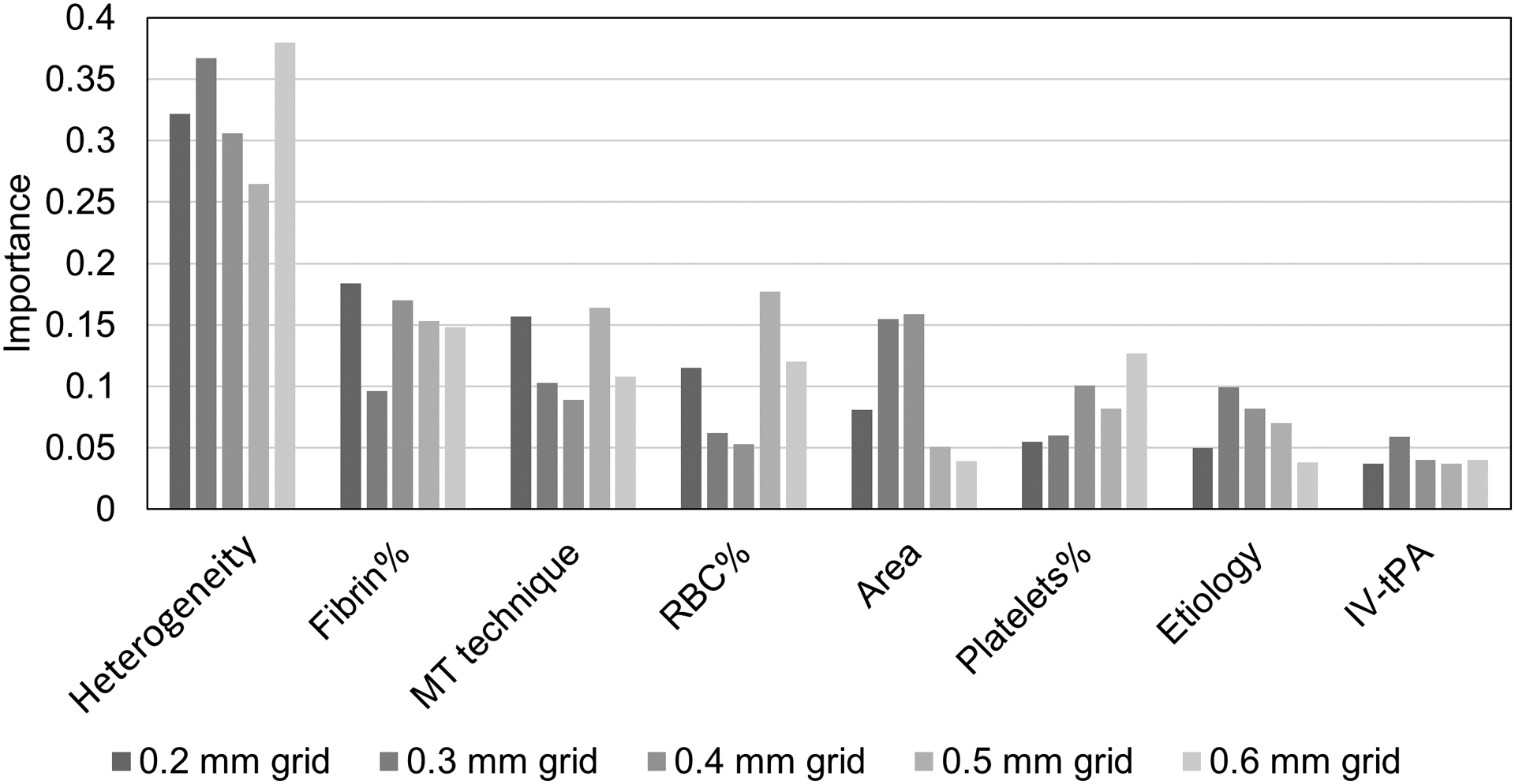

Clots in the non-FPE group were more heterogeneous than those in the FPE group with statistical significance except for the grid size of 0.5 mm (0.029 vs 0.034 p = 0.076) (Table 1). In comparison, clot compositions (RBC, fibrin, and platelets) were not statistically different between the two groups. From the ANN model, clot heterogeneity was found to be the most important factors to affect the possibility of achieving FPE, followed by fibrin content, mechanical thrombectomy technique used (direct aspiration, stent retriever, and aspiration in combination with stent retriever), RBC content, clot area, platelet content, etiology, and administration of IV-tPA (Fig. 3), regardless of the grid sizes (0.2 mm – 0.6 mm) used for SHI quantification.

Table 1.

Comparison of mean values and standard deviation (in parentheses) for clot compositions, size, number of fragments, and heterogeneity between cases with first pass effect and without.

| FPE | Non-FPE | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 107 | 50 | |

| RBC % | 46.2 (21.8) | 48.7 (14.8) | 0.734 |

| Fibrin % | 29.7 (16.9) | 29.6 (13.6) | 0.593 |

| Platelet % | 20.5 (17.8) | 18.9 (11.4) | 0.518 |

| Size (mm2) | 44.0 (47.7) | 51.0 (70.9) | 0.530 |

| Fragments | 3.8 (2.7) | 4.0 (2.4) | 0.738 |

| SHI (0.2 mm grid) | 0.043 (0.022) | 0.050 (0.016) | 0.035* |

| SHI (0.3 mm grid) | 0.038 (0.019) | 0.044 (0.017) | 0.049* |

| SHI (0.4 mm grid) | 0.033 (0.018) | 0.039 (0.017) | 0.028* |

| SHI (0.5 mm grid) | 0.029 (0.018) | 0.034 (0.017) | 0.076 |

| SHI (0.6 mm grid) | 0.024 (0.015) | 0.031 (0.017) | 0.014* |

FPE: First pass effect; RBC: Red blood cell; SHI: Spatial heterogeneity index

Figure 3. Importance of different variables in determining the possibility of FPE.

MT: mechanical thrombectomy.

Contributing factors for clot heterogeneity

Clot heterogeneity was found only weakly correlated with clot compositions. The averaged Pearson’s correlation coefficients across different grid sizes were 0.199, −0.219, −0.011, −0.140, 0.014, and −0.106 for RBC content, fibrin content, platelets content, white blood cell content, clot size, and number of clot fragments, respectively (Table S1 in the supplementary materials). The differences of clot SHI values across different stroke etiologies, thrombectomy techniques, and administration of IV-tPA were also non-significant regardless of the grid size used for SHI quantification.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that clots which required multiple passes to be removed (non-FPE group) had higher heterogeneity than those with FPE, possibly due to variations in the mechanical interaction between clots and thrombectomy devices. During thrombectomy, pulling back the aspiration catheter and/or stent retriever will apply tensional load to the clot to fight against the hemodynamic and friction forces. For a heterogeneous clot, such tensional load can cause significant clot elongation, thinning and eventual fracture at the softer and weaker RBC-rich locations, leading to residual or recurrent occlusion and iatrogenic emboli and the need of repeated thrombectomy passes.3 Although the difference in SHI values between FPE and non-FPE groups was found to be small (0.033 vs 0.039 for grid size of 0.4 mm) in this clot cohort, the actual heterogeneity for clots in the non-FPE group might be underestimated as the clots were more fragmented with more clot mass along the boundary compared to those retrieved in the FPE group. As described in the SHI quantification method, fragmented clots with more mass in the boundary tends to have a lower SHI value than that before fragmentation. The difference in SHI of in situ clots between the FPE and non-FPE groups is expected to be larger.

Contrary to what has been reported in the literature, clot composition was found to be not significantly associated with recanalization result. We found clot composition to be not statistically different between the FPE and non-FPE groups, while multiple groups have reported that fibrin-rich clots are associated with more device-passes to recanalize based on histological analysis on retrieved clots.10,11 However, their conclusion might be biased as clots retrieved from cases even with incomplete recanalization were also included for analysis and clots retrieved in such cases cannot represent the in situ clot composition. We hypothesized that the RBC-rich regions of a clot are more prone to fracture resulting in residual occlusions, and highly heterogenous clots are more likely to embolize in small fragments that migrate to more distal vessels. This result in RBC-rich regions to be less likely to be retrieved as the pass number increases. This hypothesis is supported by a published histological analysis showing that RBC content of retrieved clots decreases while the fibrin content increases with each pass.12As a result, the inclusion of retrieved clots from patients with non-complete recanalization (TICI <2C) and assumingly more passes likely overestimate the percentage of fibrin within the obstructive clot.

Although clot composition was not associated with pass number for complete recanalization, we found clots can have a large range of heterogeneity even with the same composition (Fig. 2). Different compared to clot composition which evaluates only the bulk percentages of clot components, the SHI in this study evaluates how unevenly the soft RBC area intersects with other clot areas. During thrombectomy, device withdrawal can apply tensional load to the clot, causing clot elongation and weakening and triggering multi-stage fragmentation for heterogeneous clot at its weakest RBC-rich locations.3 Clots with the same compositions may have different heterogeneity and therefore respond differently to thrombectomy devices. Compared to clot bulk composition, clot heterogeneity might be an equally or more important indicator in determining clot responses to thrombectomy devices, which was verified by the ANN model. This result suggests that clinical tools capable of measuring clot heterogenicity and drive selection of optimized tools and techniques may result in higher FPE and final complete recanalization rates.

From the ANN model, clot heterogeneity was found to be the most important factor to predict FPE. The effect of thrombectomy technique and devices on FPE rate has attracted a lot of attention recently but the findings are not unified. In a retrospective study of the ETIS Registry, a combined aspiration and stent retriever technique was associated with a higher rate of FPE.13 However, from the most recently published results of the ASTER2 trial, the FPE rates between the combined technique and stent retriever alone were not significantly different.14 Based on our results, clot heterogenicity is a critical structural feature that should drive the optimization and selection of thrombectomy technique and devices to maximize FPE.

The importance of clot heterogeneity also calls attention for making realistic clot analogs for preclinical testing of thrombectomy devices. Most clot analogs reported in the literature are structurally homogeneous and phantom models cannot accurately generate frictional forces to resist tensional loads of thrombectomy devices,15–17 which could be a reason for the overestimated recanalization rates in pre-clinical models.18 Research to improve testing platforms and consistently fabricate clot analogs with heterogeneous structure similar to patient clots is warranted. The SHI developed in this study can also be used to validate the heterogeneity of clot analogs and benchmark with clots retrieved from patients.

None of the factors investigated in this study (clot composition, stroke etiology, thrombectomy technique, administration of IV-tPA) was correlated to clot heterogeneity. Clot location, hemodynamics, hematology, patient demographics, and other pathological factors might be correlated with clot heterogeneity and future work is needed.

LIMITATIONS

First, in this study we replicated the commonly accepted histological technique to analyze one cross-section slice of the clot. Although the cross-section was selected to include as large clot area as possible for analysis and each clot fragment from each patient was analyzed, clot structural variance across the whole clot was not captured. Similarly, the SHI in this study measures the heterogeneity in a 2D plane. Although 3D heterogeneity analyses could be performed applying the same method to different imaging modalities, attempts from our group to employ CT and MR (including a research 7T magnet) were not successful given the limited spatial resolution and specificity of detecting different clot components. Second, the heterogeneity quantification was based on histology of clots that were retrievable by thrombectomy devices, therefore, cases with clots remaining in the cerebral vessels (TICI < 2c) were not included. Techniques that can accurately quantify the heterogeneity of in situ clots may provide insights into the biomechanics of incomplete or failed recanalization and may help with the selection of the optimum thrombectomy device and technique prior intervention. However, in our knowledge there is no clinically available tool with the sufficient spatial resolution and histological specificity and sensitivity. Intravascular imaging techniques such as laser angioscopy,19 diffuse reflectance spectroscopy,20 optical coherence tomography,21 ultrasound,22 and bioimpedance,23 have shown the capability of characterizing clot types or composition but further development and clinical trial is required for reliable heterogeneity quantification. Third, the spatial heterogeneity of other clot components (including fibrin, platelets, von Willebrand factor, leukocytes, and neutrophil extracellular traps) and their associations with FPE rate and etiology were not calculated in this study due to the limited specificity of the MSB staining. Forth, the clot cohort in this study did not include posterior occlusion, ICA occlusion, or distal occlusion. Future studies on the heterogeneity of clots from these occlusions and its effect on recanalization outcome are warranted.

CONCLUSION

Clot heterogeneity is the most important factor associated with FPE in thrombectomy and the SHI can be a useful metric to quantify clot heterogeneity. Clinical tools capable of informing the in situ clot heterogeneity and driving the selection of specific thrombectomy device and technique may improve the possibility of achieving FPE.

Supplementary Material

Funding Statement

This work was supported by National Institute of Health grant number NS105853.

Footnotes

Ethics Approval

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Mayo Clinic (Rochester, Minnesota): IRB 16–001131. A waiver of consent was granted.

Competing Interests Statement

MJG is on the editorial board of JNIS. None for other authors.

Data Sharing

The authors are willing to share any additional unpublished data upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brinjikji W, Nogueira RG, Kvamme P, Layton KF, Delgado Almandoz JE, Hanel RA, Mendes Pereira V, Almekhlafi MA, Yoo AJ, Jahromi BS, et al. Association between clot composition and stroke origin in mechanical thrombectomy patients: Analysis of the Stroke Thromboembolism Registry of Imaging and Pathology. J. Neurointerv. Surg 2021;1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boodt N, Snouckaert van Schauburg PRW, Hund HM, Fereidoonnezhad B, McGarry JP, Akyildiz AC, van Es ACGM, De Meyer SF, Dippel DWJ, Lingsma HF, et al. Mechanical Characterization of Thrombi Retrieved With Endovascular Thrombectomy in Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke. Stroke. 2021;52:2510–2517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu Y, Zheng Y, Reddy AS, Gebrezgiabhier D, Davis E, Cockrum J, Gemmete JJ, Chaudhary N, Griauzde JM, Pandey AS, et al. Analysis of human emboli and thrombectomy forces in large-vessel occlusion stroke. J. Neurosurg 2020;134:893–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luthman AS, Bouchez L, Botta D, Vargas MI, Machi P, Lövblad KO. Imaging Clot Characteristics in Stroke and its Possible Implication on Treatment. Clin. Neuroradiol 2020;30:27–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Di Meglio L, Desilles JP, Ollivier V, Nomenjanahary MS, Di Meglio S, Deschildre C, Loyau S, Olivot JM, Blanc R, Piotin M, et al. Acute ischemic stroke thrombi have an outer shell that impairs fibrinolysis. Neurology. 2019;93:E1686–E1698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu RG, Ariëns RAS. Insights into the composition of stroke thrombi: Heterogeneity and distinct clot areas impact treatment. Haematologica. 2020;105:257–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fitzgerald S, Wang S, Dai D, Murphree DH, Pandit A, Douglas A, Rizvi A, Kadirvel R, Gilvarry M, McCarthy R, et al. Orbit image analysis machine learning software can be used for the histological quantification of acute ischemic stroke blood clots. PLoS One. 2019;14:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pomerantz AE, Song YQ. Quantifying spatial heterogeneity from images. New J. Phys 2008;10. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mhaskar HN, Micchelli C a. How to Choose an Activation Function. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 6 1994;319–326. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maekawa K, Shibata M, Nakajima H, Mizutani A, Kitano Y, Seguchi M, Yamasaki M, Kobayashi K, Sano T, Mori G, et al. Erythrocyte-rich thrombus is associated with reduced number of maneuvers and procedure time in patients with acute ischemic stroke undergoing mechanical thrombectomy. Cerebrovasc. Dis. Extra 2018;8:39–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jolugbo P, Ariëns RAS. Thrombus Composition and Efficacy of Thrombolysis and Thrombectomy in Acute Ischemic Stroke. Stroke. 2021;52:1131–1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duffy S, Mccarthy R, Farrell M, Thomas S, Brennan P, Power S, O’Hare A, Morris L, Rainsford E, Maccarthy E, et al. Per-Pass Analysis of Thrombus Composition in Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke Undergoing Mechanical Thrombectomy. Stroke. 2019;50:1156–1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Staessens S, François O, Brinjikji W, Doyle KM, Vanacker P, Andersson T, De Meyer SF. Studying Stroke Thrombus Composition After Thrombectomy: What Can We Learn? Stroke. 2021;3718–3727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lapergue B, Blanc R, Costalat V, Desal H, Saleme S, Spelle L, Marnat G, Shotar E, Eugene F, Mazighi M, et al. Effect of Thrombectomy with Combined Contact Aspiration and Stent Retriever vs Stent Retriever Alone on Revascularization in Patients with Acute Ischemic Stroke and Large Vessel Occlusion: The ASTER2 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA - J. Am. Med. Assoc 2021;326:1158–1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu Y, Reddy AS, Cockrum J, Ajulufoh M, Zheng Y, Shih AJ, Pandey AS, Savastano LE. Standardized Fabrication Method of Human-Derived Emboli with Histologic and Mechanical Quantification for Stroke Research. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2020;29:105205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu Y, Zheng Y, Reddy AS, Gebrezgiabhier D, Davis E, Cockrum J, Gemmete JJ, Chaudhary N, Griauzde J, Pandey AS, et al. Analysis of human emboli and thrombectomy forces in large vessel occlusion stroke. J. Neurosurg 2020;ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu Y, Larco JLA, Madhani SI, Shahid AH, Quinton RA, Kadirvel R, Kallmes DF, Brinjikji W, Savastano LE. A thrombectomy model based on ex vivo whole human brains. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol 2021;42:1968–1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu Y, Abbasi M, Arturo Larco JL, Kadirvel R, Kallmes DF, Brinjikji W, Savastano L. Preclinical testing platforms for mechanical thrombectomy in stroke: a review on phantoms, in--vivo animal, and cadaveric models. J. Neurointerv. Surg 2021;13:816–822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Savastano LE, Zhou Q, Smith A, Vega K, Murga-Zamalloa C, Gordon D, McHugh J, Zhao L, Wang MM, Pandey A, et al. Multimodal laser-based angioscopy for structural, chemical and biological imaging of atherosclerosis. Nat. Biomed. Eng 2017;1:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Skyrman S, Burström G, Aspegren O, Lucassen G, Terander AE-, Edström E, Arnberg F, Ohlsson M, Mueller M, Andersson T. Identifying clot composition using intravascular diffuse reflectance spectroscopy in a porcine model of endovascular thrombectomy. J. Neurointerv. Surg 2021;1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ding Y, Abbasi M, Eltanahy AM, Jakaitis DR, Dai D, Kadirvel R, Kallmes DF, Brinjikji W. Assessment of Blood Clot Composition by Spectral Optical Coherence Tomography: An In Vitro Study. Neurointervention. 2021;16:29–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu H-C, Abbasi M, Ding YH, Roy T, Capriotti M, Liu Y, Fitzgerald S, Doyle KM, Guddati MN, Urban MW, et al. Characterizing blood clots using acoustic radiation force optical coherence elastography and ultrasound shear wave elastography. Phys. Med. Biol 2021;66:035013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu Y, Bhambri A, Adapa A, Shih A, Pandey A. Abstract P782: Bioimpedance as a Means to Quantify Clot Composition and Guide Selection of Thrombectomy Devices. Stroke. 2021;52. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors are willing to share any additional unpublished data upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.