Keywords: cardiorespiratory fitness, genomics, metabolomics, proteomics, transcriptomics

Abstract

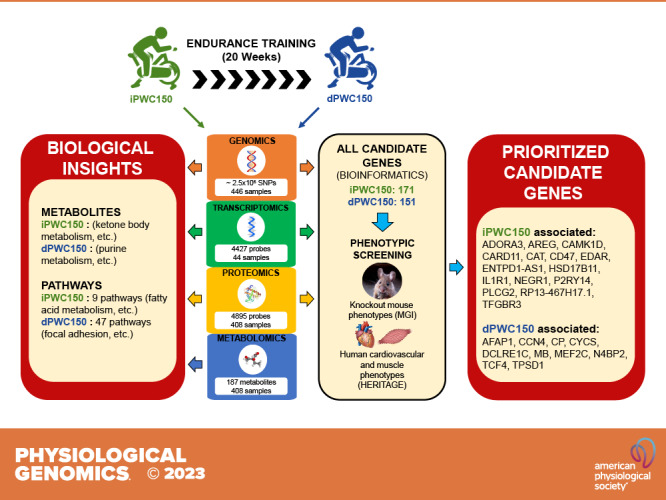

Submaximal exercise capacity is an indicator of cardiorespiratory fitness with clinical and public health implications. Submaximal exercise capacity and its response to exercise programs are characterized by heritability levels of about 40%. Using physical working capacity (power output) at a heart rate of 150 beats/min (PWC150) as an indicator of submaximal exercise capacity in subjects of the HERITAGE Family Study, we have undertaken multi-omics and in silico explorations of the underlying biology of PWC150 and its response to 20 wk of endurance training. Our goal was to illuminate the biological processes and identify panels of genes associated with human variability in intrinsic PWC150 (iPWC150) and its trainability (dPWC150). Our bioinformatics approach was based on a combination of genome-wide association, skeletal muscle gene expression, and plasma proteomics and metabolomics experiments. Genes, proteins, and metabolites showing significant associations with iPWC150 or dPWC150 were further queried for the enrichment of biological pathways. We compared genotype-phenotype associations of emerging candidate genes with reported functional consequences of gene knockouts in mouse models. We investigated the associations between DNA variants and multiple muscle and cardiovascular phenotypes measured in HERITAGE subjects. Two panels of prioritized genes of biological relevance to iPWC150 (13 genes) and dPWC150 (6 genes) were identified, supporting the hypothesis that genes and pathways associated with iPWC150 are different from those underlying dPWC150. Finally, the functions of these genes and pathways suggested that human variation in submaximal exercise capacity is mainly driven by skeletal muscle morphology and metabolism and red blood cell oxygen-carrying capacity.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Multi-omics and in silico explorations of the genes and underlying biology of submaximal exercise capacity and its response to 20 wk of endurance training were undertaken. Prioritized genes were identified: 13 genes for variation in submaximal exercise capacity in the sedentary state and 5 genes for the response level to endurance training, with no overlap between them. Genes and pathways associated with submaximal exercise capacity in the sedentary state are different from those underlying trainability.

Listen to this article’s corresponding podcast at https://apspublicationspodcast.podbean.com/e/omics-and-submaximal-work-capacity-and-trainability/.

INTRODUCTION

Cardiorespiratory fitness plays an important role in the modulation of risk for cardiometabolic diseases and other health outcomes, including aging and mortality (1). It is useful for understanding of the health benefits associated with regular exercise to distinguish between intrinsic cardiorespiratory fitness and acquired cardiorespiratory fitness (2). Most epidemiological studies of cardiorespiratory fitness and health outcomes are based on indicators of maximal cardiorespiratory fitness or predicted maximal cardiorespiratory fitness from submaximal levels (3). However, submaximal indicators of cardiorespiratory fitness are also of considerable importance (4, 5), as it is not always possible or desirable to test a person to exhaustion.

There is a strong interest in submaximal cardiorespiratory fitness indicators for applications in large population studies, studies of old people, and patients affected by any number of clinical conditions. The demand for simple and less demanding indicators of fitness is such that several investigators have even proposed to predict the cardiorespiratory fitness of adults from personal characteristics and behavioral traits with no exercise testing involved. As the focus of this paper is on the biology underlying submaximal cardiorespiratory fitness, the large body of literature dealing with the prediction of maximal cardiorespiratory fitness from submaximal indicators is not of interest here. Tests typically used to assess submaximal cardiorespiratory fitness in various settings (6) include submaximal treadmill, cycling, paced walking, and step tests. Submaximal fitness tests that have received attention for decades focus on the power output at a given submaximal heart rate (HR). Examples of such tests include physical working capacity (PWC) at heart rates (HRs) of 130 beats/min, 150 beats/min (PWC150), or 170 beats/min. For instance, PWC at an HR of 130 beats/min has been used as an indicator of fitness in studies with older participants (7), PWC at an HR of 170 beats/min has been used with younger populations (8, 9), and PWC150 has been used with heterogeneous populations (10, 11).

PWC tests are based on the relationship between progressively increasing workloads and the HR response in a relatively steady state at each workload. The estimated power output at the targeted HR (e.g., 150 beats/min) is interpolated when flanked by a lower and higher exercise HR. When the targeted HR is higher than the highest achieved HR, the targeted PWC is extrapolated, again assuming a linear relation between workload and HR. PWC tests are only moderately correlated with other indicators of cardiorespiratory fitness, including maximal oxygen consumption (V̇o2max) (9, 12), indicating that they measure aspects of fitness that are not captured fully in maximal exercise tests leading to exhaustion. Moreover, baseline indicators of submaximal exercise capacity are largely independent of their responses to an exercise training program (13–15). Thus, maximal and submaximal tests of cardiorespiratory fitness do not measure the same combination of biological determinants of exercise capacity. V̇o2max tends to reflect primarily the performance of the oxygen delivery system, which is conditioned by stroke volume (SV), cardiac output, and the oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood as assessed by total hemoglobin content (16–19). In contrast, submaximal exercise capacity is highly dependent on central factors but with a strong contribution from peripheral ones, including local blood flow and skeletal muscle morphology and metabolism (15).

In a series of genetic studies performed by our group, one study of PWC150 performed in sedentary adopted and biological siblings reported that the heritability reached ∼40% with data adjusted for age, sex, body mass, and composition (10). This observation was largely confirmed by the HERITAGE Family Study for several indicators of submaximal exercise capacity (20, 21). Likewise, significant familial aggregation and heritability levels were found for HR, blood pressure, SV, and cardiac output during submaximal exercise at 50 W and at 60% of maximal exercise capacity in sedentary adults of HERITAGE (22). The variability in responsiveness to the endurance training program of HERITAGE was also partly explained by significant genetic components (heritability ranging from 22% to 57%) for the gains in submaximal working capacity (20, 21), with slightly lower heritability levels for changes in submaximal exercise HR, blood pressure, SV, and cardiac output (22, 23). The gains in submaximal exercise capacity with training were further linked to several single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) on chromosome 13q12 in a region encoding MIPEP and SGCG (24).

Although the physiology of submaximal exercise capacity has received attention, little is known about genes, pathways, networks, and noncoding regulatory and other genomic features contributing to individual differences in submaximal physical working capacity and its trainability. The present study was designed to address these topics using the genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, metabolomic, and phenotype resources of the HERITAGE Family Study, interrogated through a comprehensive bioinformatics pipeline. The following hypotheses were addressed. First, assuming that there are only moderate correlations between V̇o2max and submaximal exercise capacity, we hypothesized that the panel of prioritized genes will be substantially different between intrinsic V̇o2max [as previously reported by Ghosh et al. (25)] and intrinsic PWC150 (iPWC150). Second, assuming that there are only weak correlations between baseline submaximal exercise capacity and its response to exercise training, we further hypothesized that the panel of prioritized genes and pathways will differ markedly between iPWC150 and its training response (dPWC150). Third, we hypothesized that the panel of prioritized genes and pathways for both iPWC150 and dPWC150 will be dominated by genes and pathways associated primarily with skeletal muscle morphology and metabolism and oxygen transport capacity of the blood. We further posit that in silico “experiments” involving existing physiological and metabolic traits measured on the HERITAGE subjects and in mouse datasets relevant to cardiorespiratory fitness will provide further evidence for the genes identified in our study.

This is the first unbiased and comprehensive omics exploration of physiological and molecular correlates of submaximal work capacity and its response to endurance exercise training. It provides multiple biomarker targets that could be further investigated in experimental models and other human cohorts with exercise training data.

METHODS

HERITAGE Family Study

The HERITAGE Family Study has been previously described, including full details on study design and inclusion and exclusion criteria (26, 27). This was a single-arm intervention (i.e., nonrandomized) with no control group. The Consensus on Exercise Reporting Template (28) guidelines for this study are provided in Supplemental Table S1. Briefly, 855 Black and White subjects from 218 families across 4 clinical sites were recruited to participate in an endurance exercise training study. Among them, 446 adults (216 men and 230 women) from 97 families of European descent, who were confirmed sedentary and had taken two maximal exercise tests to exhaustion at baseline, constituted the population of the present study. Genomic, metabolomic, and skeletal muscle gene expression and biochemical assays were not available for Black subjects in HERITAGE. Inclusion and exclusion criteria included age (17–65 yr), physical activity level (physically inactive the previous 6 mo), body mass index below 40 kg/m2, normotensive or mildly hypertensive (<160/100 mmHg), not taking medications for hypertension, diabetes, or dyslipidemia, and no history of certain medical conditions (26). The study protocol had been approved by the Institutional Review Boards at each of the participating centers of the HERITAGE Family Study consortium. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant. All research was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Exercise Intervention

Each subject in HERITAGE exercised three times per week for 20 wk on cycle ergometers. The intensity of the exercise was customized for everyone based on HR and V̇o2max measurements taken at a baseline test. Details of the exercise training protocol can be found elsewhere (26). Briefly, subjects trained at the HR associated with 55% of baseline V̇o2max for 30 min per session for the first 2 wk. The duration and intensity were gradually increased every 2 wk until reaching 50 min and 75% of the HR associated with baseline V̇o2max. This level was maintained for the final 6 wk of training. All exercise was performed on Universal Aerobicycles (Cedar Rapids, IA), and power output was controlled by direct HR monitoring using the Universal Gym Mednet (Cedar Rapids, IA) computerized system. Each exercise session was supervised to ensure that the equipment was working properly and that the participants were compliant with the protocol. As each participant was used as his/her own control in the exercise intervention, randomization was not considered a relevant criterion for the study design.

Exercise Tests

A progressive, continuous cycle ergometer test to exhaustion was performed at baseline and 24 h after the last exercise training session. The exercise test was performed on a SensorMedics 800S (Yorba Linda, CA) cycle ergometer using a SensorMedics 2900 metabolic measurement cart (29). Briefly, subjects exercised at a power output of 50 W for 3 min, followed by increases of 25 W each 2 min until volitional exhaustion. For older, smaller, or less fit individuals, the test was started at 40 W, with increases of 10–20 W each 2 min thereafter. Maximal oxygen uptake (V̇o2max) was defined as previously reported (18, 21).

PWC150 Calculation

PWC150 was interpolated from the HR-power output relationship across all stages of the progressive maximal exercise test using linear regression models fit for each participant. From each regression model, the β estimate for HR was multiplied by 150 and added to the intercept value to calculate PWC150. Of a total of 892 PWC calculations (baseline plus posttraining), only 11 (or 1.2%) had to be extrapolated (i.e., their HR did not reach 150 during the maximal exercise test). To calculate the change in PWC150 (dPWC150), the iPWC150 value was subtracted from the posttraining PWC150 value.

Cardiovascular Phenotype Measurement

Submaximal exercise phenotypes include HR, SV, cardiac output, systolic blood pressure (SBP), and oxygen consumption (V̇o2) at 50 W and 60% of V̇o2max measured at baseline and posttraining exercise tests (29, 30). The values used in the present study represent the mean of the responses at each power output (50 W and 60% of V̇o2max) from two submaximal tests, both before and after training. HR was recorded by electrocardiography, and blood pressure was measured using Colin STBP-780 automated units (San Antonio, TX) with recordings confirmed by technicians wearing headphones (31). SV and cardiac output were assessed by the CO2 rebreathing method (32). Other exercise phenotypes of interest here included maximal workload achieved and workload at the ventilatory threshold (33).

Percent body fat, fat mass, and fat free mass were assessed by hydrostatic weighing, as previously described (34). Percent body fat was estimated from body density using sex- and ethnic-specific equations (35–38). Visceral adipose tissue (VAT) was assessed by computed tomography, as previously described (34). Body mass index was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared (kg/m2).

Muscle Phenotype Measurement

A subset of HERITAGE participants underwent muscle biopsies from the vastus lateralis before and after the exercise training program (39). Histochemical analysis was performed based on the staining properties of ATP to identify skeletal muscle fibers as type I, IIA, and IIB. The number of capillaries around each of these fibers was counted to determine the capillary density and area per capillary of each fiber type. Skeletal muscle enzyme activities were measured using spectrophotometric techniques on homogenized muscle samples (39). The maximal activity of the following enzymes was measured: carnitine palmitoyl transferase, citrate synthase, creatine kinase, cytochrome c oxidase, GAPDH, 3-β-hydroxyacyl CoA dehydrogenase, hexokinase, phosphofructokinase, and phosphorylase.

All muscle and cardiovascular phenotypes were measured at baseline and posttraining (24 and 72 h for cardiovascular traits and 96 h after the last exercise session for muscle), and the change in response to the exercise training program (i.e., Δ) was calculated by subtracting the baseline value from the posttraining value.

Genome-Wide Genotyping

Genome-wide genotyping was performed using the Illumina HumanCNV370-Quad v3.0 BeadChips on Illumina BeadStation 500GX platform. The genotype calls were determined via the Illumina GenomeStudio software, and all samples were called in the same batch to eliminate batch-to-batch variation. Monomorphic SNPs, SNPs with only one heterozygote, and SNPs with more than 30% missing data were filtered out. Twelve samples were genotyped twice with 100% reproducibility across all SNPs. All GenomeStudio genotype calls with a GenTrain score of <0.885 were checked and confirmed manually. Quality control of the genome-wide association study (GWAS) SNP data confirmed all family relationships and found no evidence of DNA sample mix-ups.

Imputation was performed using a CEU reference panel (Northern and Western European ancestry) consisting of 120 haplotypes from HapMap Phase II data (release 22, build 36) and MACH software (40). A total of 2,396,589 (324,611 directly typed and 2,071,978 imputed) SNPs were tested for association with iPWC150 and dPWC150 residuals. Residuals were standardized to a zero mean and unit variance with adjustment for age within sex-by-generation subgroups as previously described (40). ΔPWC150 residuals also adjusted for intrinsic PWC150 (i.e., Δ values are independent of baseline value).

Overall Analytic Strategy

As estimates for iPWC150 and dPWC150 were obtained under strictly controlled experimental settings, the available sample sizes for GWAS were necessarily smaller compared with conventional GWAS that are based on population-level sampling of cases and controls. Smaller sample sizes affect statistical power, leading to increased type II error rates (false negatives), when analysis is guided solely by strict statistical thresholds. The same is true for other omics technologies, especially when dealing with heterogeneous human samples. To address this problem of overreliance on statistical thresholding while maintaining a consistent gene selection strategy, we used more permissible nominal P value thresholds (0.05−1 × 10−4 range, heuristically determined depending on analysis) to identify gene candidates from genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics studies [adjusted P values were also calculated in all cases via the false discovery rate (“FDR”) method using the rstatix R package]. The union of the candidate genes determined from each analysis was subsequently tested for phenotypic associations to finally prioritize candidate iPWC150 and dPWC150 genes. We adopted the more inclusive union-based strategy for primary gene selection instead of an intersection-based approach because different technology platforms are likely to capture different aspects of the underlying phenotype that would be missed if the focus was only on the common genes. This was confirmed by the observation that the overlap among top-scoring genes from each analysis in the present study was indeed low. In summary, we relied more on phenotypic corroboration, instead of strict statistical filtering, for candidate gene prioritization.

The analytic approach is divided into a discovery section and a validation section (Fig. 1). The discovery section is concerned with the identification of candidate genes, associated with iPWC150 or dPWC150, through an integrative bioinformatics analysis of different data streams arising from genomics (GWAS), baseline skeletal muscle transcriptomics, and baseline plasma proteomics of HERITAGE cohort samples. A separate metabolomics analysis of associations with iPWC150 and dPWC150 was also carried out. For GWAS analysis, we exploited data from several expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) datasets to assess the impact of iPWC150- or dPWC150-associated SNPs in influencing nearby gene expression (cis-eQTLs). In addition, we examined the effects of sequence variation on biological processes through pathway enrichment analysis of genes proximal to associated SNPs. For transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data, we investigated the association of baseline analyte expression (genes, proteins, or metabolites) with iPWC150 or dPWC150 via multivariate regression modeling after adjustments for age, sex, baseline body mass index, and, additionally, iPWC150 (for models of dPWC150). Genes, proteins, and metabolites showing nominally significant associations were further queried for enrichment of biological pathways.

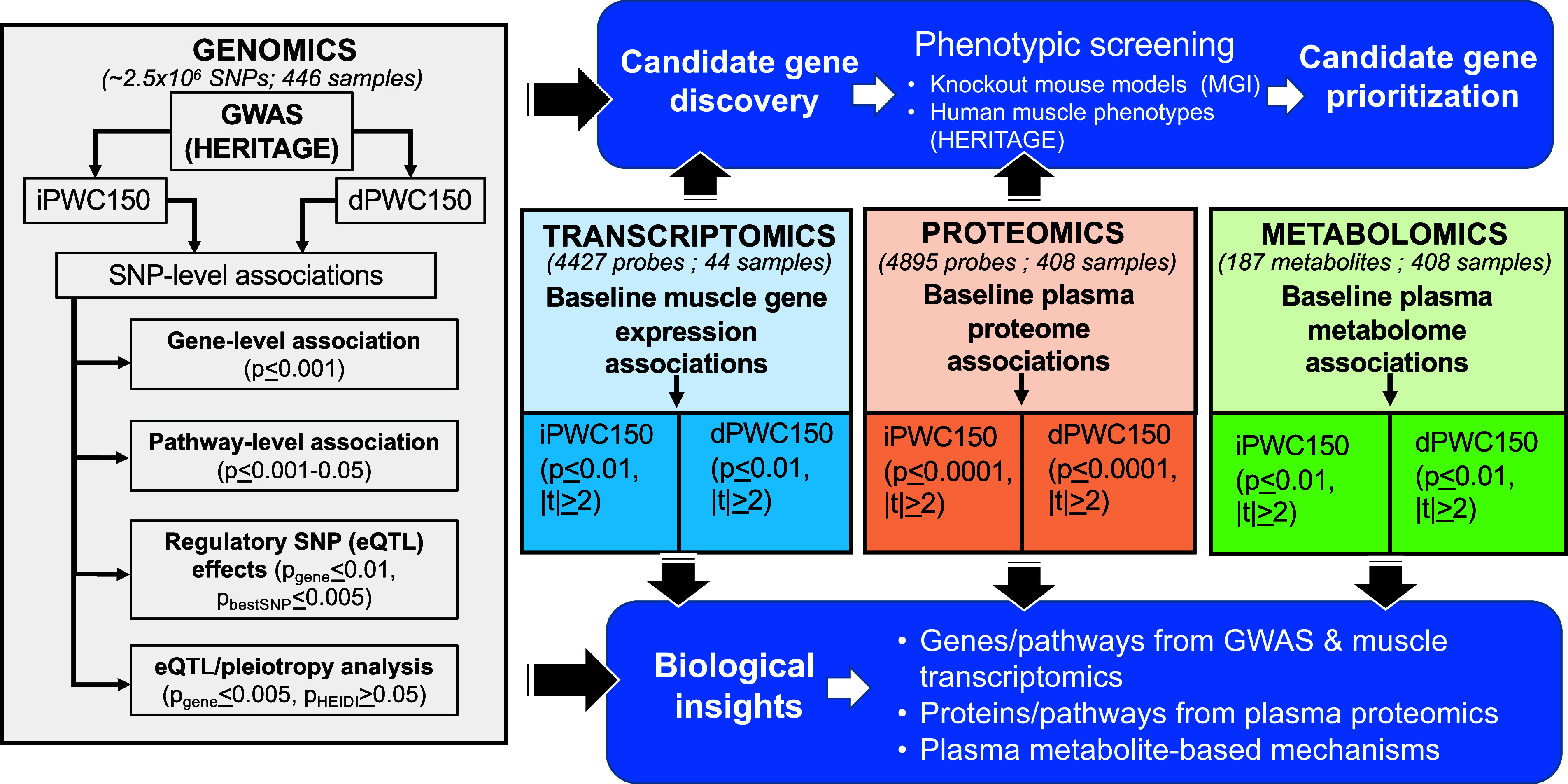

Figure 1.

Schematic of the overall analysis approach. The four streams of analysis are shown in colored boxes: genome-wide association study (GWAS; gray), transcriptomics (blue), proteomics (orange), and metabolomics (green). For each stream, analysis is conducted independently for intrinsic and delta physical working capacity at a heart rate of 150 beats/min (iPWC150 and dPWC150, respectively) associations. The GWAS analysis pipeline consisted of using the single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP)-level association data to compute gene- and pathway-level associations and to conduct expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) analysis in skeletal muscle, adipose, and whole blood, including tests for pleiotropy of candidate eQTL SNPs. For transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics data, the respective expression levels were tested for association to iPWC150 or dPWC150 via linear models, after adjustments for age, sex, and body mass index. GWAS, transcriptome, and proteome data were analyzed to identify a list of candidate genes (top blue box). The candidate genes were then examined for phenotypes in knockout mouse models (when available) and human cardiovascular and muscle-relevant phenotypes measured on HERITAGE participants. The results from the phenotype analyses were used to identify a list of prioritized candidate genes. in addition, the results from GWAS, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics were also interrogated to identify biological mechanisms (pathways) associated with iPWC150 and dPWC150 (bottom blue box).

From each of the genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic data streams, a set of iPWC150- and dPWC150-associated candidate genes were identified and further evaluated for phenotypic corroboration. We interrogated potential genotype-phenotype associations of the candidate genes through an analysis of functional consequences of gene knockouts in mouse models (when available) from the MGI database. In addition to knockout mouse models, we also investigated the possible association of SNPs in the candidate genes with resting muscle-specific and resting and exercise-dependent cardiovascular phenotypes in HERITAGE subjects as described in Associations of SNPs With Cardiovascular and Skeletal Muscle Traits. As the metabolomics results are less suitable for the direct identification of candidate genes, we focused our analysis of metabolomics results more on the biological mechanisms affected in each of iPWC150 and dPWC150 comparisons.

Gene Scoring and Pathway Analysis

Pathway enrichment analysis of GWAS data was performed via two methods [Pascal (41) and GSA-SNP2 (42)], and the common and unique pathways identified in each method were determined. Pathways were obtained from the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG; c2.cp.kegg.v7.0.symbols, 186 gene sets), Hallmark (h.all.v7.0.symbols, 50 gene sets), and Gene Ontology Biological Process (GOBP; c5.bp.v7.0.symbols, 7,349 gene sets) databases downloaded from the Molecular Signature Database (MSigDB, RRID:SCR_016863) (v5.2) (43). Enrichment analysis was restricted to pathways containing between 15 and 200 gene members. Both Pascal and GSA-SNP2 rely on computing a gene-wide association P value from the P values of individual SNPs mapping to the gene (±20 kb upstream and downstream sequences) using method-specific statistics. Briefly, for GSA-SNP2, an adjusted gene score [adj(gi)] is generated for each gene according to the following equation:

where Pibest is the best P value among the SNPs assigned to gene gi and C(gi) is the estimated gene score derived from a monotonic cubic spline fit of the –log10(best P value) to the number of SNPs mapped to a gene. These adjusted gene scores are then used to arrive at a Z statistic for each pathway gene set Pj(1 ≤ j ≤ K) [Z(Pj)] according to the following equation:

where Pj is the average-adjusted gene score in the gene set, Pj and m and σ are the mean and standard deviation (SD), respectively, of all the adjusted gene scores, and Nj is the number of genes in the gene set. The pathway P value is derived from a one-tailed Z test, which offers better control of the false positive rate for GWAS data compared with a two-tailed test (44). In contrast to GSA-SNP2 scores, which are derived from the best P value of the gene-associated SNPs, in Pascal, we used the sum of χ squares (SOCS) statistic defined as follows:

where zi refers to the z score of the ith SNP (I = 1…n) mapped to a gene. These gene scores are then converted to pathway scores via empirical sampling using Monte Carlo-based methods.

Regulatory Genome Analysis: eQTLs

An eQTL-based gene-level estimate of association with iPWC150 or dPWC150 was developed via the Eugene package (34), by first combining all independent eQTLs (r2 < 0.05) found to alter expression of a gene in several eQTL datasets or by matching the eQTLs to their highest correlated proxy SNPs in the GWAS dataset (r2 > 0.8), if the eQTL SNP was not directly genotyped or imputed in GWAS. The observed GWAS association statistics of these SNPs with iPWC150 or dPWC150 were then converted to χ squares, and a gene-based sum statistic was calculated by adding all the χ squares. The statistical significance of the gene-level sum statistic was obtained via the Satterthwaite approximation method (35).

Summary Data-Based Mendelian Randomization

Evidence for a pleiotropic association of an eQTL SNP with both gene expression and genetic association to iPWC150 or dPWC150 was ascertained via the summary data-based Mendelian randomization (SMR) test (45). The SMR method tests the association of exposure (e.g., transcript) with an outcome (e.g., trait) using a genetic variant (e.g., top cis-eQTL strongly associated with gene expression) as the instrumental variable to remove nongenetic confounding. In other words, SMR tests if a transcript and phenotype are likely to be associated because of a shared causal variant (i.e., pleiotropy). Mathematically, if e is an exposure variable, o is the outcome variable, and i is an instrumental variable, then the MR estimate of the effect of exposure on outcome (beo) can be expressed as the ratio of the estimated effect of instrument on exposure (bie) and on outcome (bio), as follows:

beo = bio/bie

where bio and bie are available from gene expression, eQTL, and GWAS summary data.

To ensure that the instrument variable has a strong effect on exposure, only probes with at least one cis-eQTL at an eQTL P value < 5 × 10−8 were included in the eQTL summary data.

By itself, the SMR test reports a significant association that can arise either due to pleiotropy or linkage. In a pleiotropic model, the exposure and outcome are associated due to the same shared genetic variant. In contrast, a linkage model involves two or more genetic variants in linkage disequilibrium (LD) that affect the exposure and outcome independently. To distinguish between the two possibilities, the heterogeneity in independent instruments (HEIDI) test (45) examines the null hypothesis that a single causal variant is responsible for the observed associations to exposure and outcome. The test proceeds by considering multiple SNPs within a cis region and testing the homogeneity (or lack thereof) of the association patterns. A confirmation of the null hypothesis is interpreted as evidence in favor of the pleiotropy model. In this study, only significant SMR associations that were not significant in the HEIDI test (PHEIDI > 0.05) were retained. LD estimates were based on SNP data for 1000 Genomes European individuals (294 individuals, release 20130502_v5a) downloaded from the Eugene website (https://genepi.qimr.edu.au/staff/manuelF/eugene/download.html). eQTL data were examined from three whole blood datasets [Westra (46), CAGE (47), and GTEx_WB] and one GTEx-based dataset (48) each for skeletal muscle, subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT), and VAT.

Affymetrix Microarray Analysis

Biopsies of vastus lateralis muscle were obtained in a sample of White subjects from the Laval University (Québec) Clinical Center of HERITAGE. Total RNA was isolated from frozen muscle biopsies preserved in Tissue-Tek using TRIzol and mRNA amplified with Ambion MessageAmp Premier following the manufacturer’s instructions. Global skeletal muscle gene expression profiles were generated by hybridization to Affymetrix HG-U133 Plus 2.0 arrays. Combined muscle gene expression and PWC phenotype data were available for 44 subjects. Background-corrected, quantile-normalized, and log2-transformed expression data were obtained via Robust Multichip Averages (RMA) (49). Probe sets with normalized maximum expression of ≥50 units (5.6 in log2 scale) and a coefficient of variation of ≥10% were retained, resulting in 4,427 probes for further analysis. The relation of gene expression to iPWC150 or dPWC150 levels was modeled via multivariate linear regression in R (tidyverse, https://www.tidyverse.org/). Association results for selected genes were visualized via partial residual regression plots via the “car” package in R (https://socialsciences.mcmaster.ca/jfox/Books/Companion/). The raw microarray data for this study have been deposited with Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO; RRID:SCR_005012) (50) and are accessible through GEO Series Accession No. GSE117070.

(https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE117070). Pathway enrichment analysis of gene expression data was conducted via the Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) tool (RRID:SCR_003199) (51) using the same set of gene sets from MSigDB (KEGG, Hallmark, and GOBP) as was used for pathway analysis of GWAS data.

Proteomics Analysis

Baseline plasma proteome characterization was conducted via the SOMAScan platform from SomaLogic (www.somalogic.com) (52, 53). Briefly, archived baseline plasma samples stored at −80°C from HERITAGE were diluted in three different concentrations (40%, 1%, and 0.05%) and incubated with fluorescent single-stranded DNA aptamers (∼5,000 SOMAmers). Protein-aptamer complexes were isolated from unbound or nonspecifically bound proteins using a streptavidin bead-based immobilization procedure. Aptamers were subsequently eluted from the target proteins and quantified by their fluorescence on a DNA microarray chip. Samples were normalized to 12 hybridization control sequences within each microarray and across plates using the median signal for each dilution. After elimination of problematic analytes as reported by SomaLogic, which performed the assays for HERITAGE, 4,895 proteins were used for downstream analysis. Missing values in proteomic measurements were replaced by the median analyte expression across all samples. All proteomic abundance data were log2 normalized to approximate the normal distribution as determined by Shapiro test (54). Results of the association analysis were visualized for selected proteins via regression plots of the fitted protein expressions versus iPWC150 or dPWC150 values. The secretory status of a protein was ascertained by cross-referencing the human secretome data from the Universal Protein Resource, UniprotKB (RRID:SCR_002380, https://www.uniprot.org). Pathway enrichment analysis of proteomics data was conducted via the GSEA tool (51) using the same set of gene sets from MSigDB (KEGG, Hallmark, and GOBP) as was used for pathway analysis of GWAS data.

Metabolomics Analysis

Targeted metabolomics analyses were carried out on deproteinized archived baseline plasma samples stored at −80°C on two liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS)-based methods. In positive mode, normal phase hydrophilic interaction chromatography (HILIC) using a 2.1 × 150-mm 3-μm Atlantis column (Waters) was coupled to a 4000 QTrap triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems/Sciex) equipped with an electrospray ionization source and used a dynamic multiple reaction monitoring mechanism. In negative mode, HILIC chromatography using a 2.1 × 100-mm 3.5-μm Xbridge Amide column (Waters) was coupled to an Agilent 6490 triple quadrupole mass spectrometer equipped with an electrospray ionization source for detection using multiple reaction monitoring. Metabolite peak areas were integrated using Sciex MultiQuant software (positive mode) or Agilent Masshunter Quantitative Analysis software (RRID:SCR_015040) (negative mode). All metabolite peaks were manually reviewed for peak quality in a blinded manner by two separate analysts. Pooled plasma samples were interspersed within each analytic run at standardized intervals, enabling the monitoring and correction for temporal drift in MS performance. The drift-corrected data, measuring relative abundances of metabolites, were used without further transformation in downstream analysis. The final dataset consisted of 187 plasma metabolites measured in 408 HERITAGE White subjects. Due to the variation in estimated metabolite levels, the metabolomics data were “squished” before analysis such that for each metabolite, values at <2 percentile or >98 percentile were converted to the 2 percentile or 98 percentile values, respectively. The results of the association analysis were visualized via regression plots of the fitted metabolite expressions versus iPWC150 or dPWC150 values.

Analysis of Mouse Phenotypes

We queried the Mouse Genome Informatics (MGI; www.informatics.jax.org) database to identify and classify mouse phenotypes that are affected by knockout of the candidate genes identified from the bioinformatics (GWAS), genomic, and proteomic analyses. From the GWAS analysis of iPWC150 and dPWC150 data, genes were selected based on the collective evidence for one or more of the following: 1) top 0.1% of gene-trait association to iPWC150 or dPWC150; 2) membership in common pathways identified by GSA-SNP2 and Pascal and with gene-level GWAS association P value ≤ 0.05; 3) top 10 eQTL gene in adipose, skeletal muscle, and whole blood; and 4) gene transcriptionally affected by a pleiotropic SNP with SMR P value ≤ 5 × 10−4. From gene expression studies, genes with an association P value ≤0.05 and absolute regression coefficient ≥0.008 with iPWC150 or dPWC150 levels were selected. Similarly, plasma proteins with an association P value ≤0.0001 with iPWC150 or dPWC150 were also included. Only mouse phenotypes arising from spontaneous mutations, targeted gene knockout, or gene trap studies were considered, to avoid confounding effects in other mouse models (e.g., mutations in unrelated genes in chemical mutagenesis or multiple gene knockout-type models). Phenotypes associated with the query genes were further grouped into their “root phenotypes” according to the hierarchical ontology used in the MGI V6.07 mammalian phenotype browser.

Associations of SNPs With Cardiovascular and Skeletal Muscle Traits

Based on the bioinformatics analysis of GWAS and multi-omics-based correlations with iPWC150 and dPWC150, we identified several genes for which mapped SNPs (gene body ±50 kb upstream and downstream) were tested for associations with select resting and exercise cardiovascular and muscle-related traits. Highly correlated SNPs were removed before trait association analysis by filtering out biallelic SNPs with r2 ≤ 0.9 and MAF < 0.01, via the SNPClip module of LDLink software, using the 1000 Genomes (Phase 3) CEU reference panel for LD estimation (55). SNP-trait association was performed through the total association model of MERLIN (56) with age and sex as covariates. This model uses a variance-components framework to combine the phenotypic means model and the estimates of additive genetic, residual genetic, and residual environmental variances from a variance-covariance matrix into a single likelihood model. An association P value of ≤0.01 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Study Population and Intrinsic and Delta PWC150 Distributions

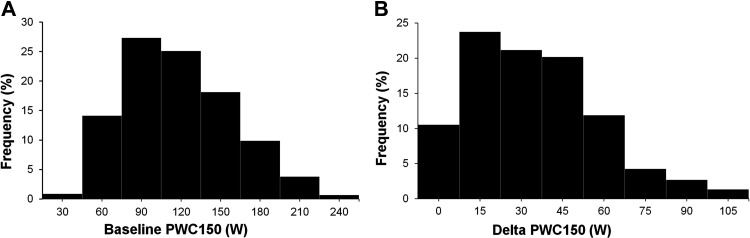

A total of 446 White subjects from the HERITAGE Family Study who completed the exercise program and had valid measures of iPWC150 and dPWC150 were available for the study. Their mean age and body mass index were 36 yr (SD = 14.6) and 25.8 kg/m2 (SD = 4.9), respectively. The basic characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1. The mean iPWC150 was 118 W (SD = 41 W), and the mean increase in PWC150 with the exercise program (dPWC150) was 33 W (SD = 25). V̇o2max per kilogram body weight increased from 33.2 (SD = 8.8) at baseline to 38.6 (SD = 9.6) posttraining. The mean dPWC150 was 31% (SD = 25), which was substantially higher than the 17% gain in V̇o2max registered for this population. The distributions of iPWC150 and dPWC150 were highly heterogeneous, as shown in Fig. 2.

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of HERITAGE White adults constituting the study population (n = 446)

| Variable | Baseline | Posttraining | Change | Percent Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 36.0 (14.6) | |||

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 25.8 (4.9) | 25.7 (5.0)† | −0.07 (0.7) | −0.2 (2.8) |

| PWC150, W | 118 (41) | 151 (51)* | 33 (25) | 31.0 (25.0) |

| Heart rate at 50 W, beats/min | 117 (17) | 106 (14)* | −11 (10) | −8.7 (7.6) |

| Workload at maximum, W | 183.3 (58.0) | 233.7 (72.6)* | 50.4 (26.5) | 28.5 (13.8) |

| V̇o2max, mL/min | 2449 (725) | 2843 (798)* | 393 (216) | 16.9 (9.0) |

| V̇o2max, mL/kg/min | 33.2 (8.8) | 38.6 (9.6)* | 5.4 (3.1) | 17.2 (9.8) |

Values given as means (SD). PWC150, physical working capacity at a heart rate of 150 beats/min; V̇o2max, maximal oxygen consumption. *P < 0.0001 and †P < 0.05 for difference compared with the baseline value.

Figure 2.

Distribution of intrinsic and delta physical working capacity at a heart rate of 150 beats/min (iPWC150 and dPWC150, respectively) responses to training in HERITAGE subjects. A: distribution of iPWC150 values in HERITAGE subjects in the sedentary state ordered from low to high. B: histogram of dPWC150 values across 10 classes of response levels to the exercise training program in the same set of HERITAGE White adults. Results are based on complete data on 446 White adults.

Our first hypothesis, which stipulates that the panel of identified genes will be substantially different between intrinsic V̇o2max and iPWC150, assumed that there was only a moderate correlation between intrinsic V̇o2max and iPWC150. This assumption was borne out by the fact that the common variance between intrinsic V̇o2max and iPWC150, both adjusted for age and sex, reached 32% (P < 0.0001), implying that there was substantial differential variance between both indicators of cardiorespiratory fitness.

Our second hypothesis specified that the panel of prioritized genes will differ markedly between iPWC150 and its training response. This was predicated on the fact that there would be only weak correlations between iPWC150 and dPWC150. Again, the data strongly suggested that it was truly the case, as the correlation between iPWC150 (adjusted for age and sex) and dPWC150 (adjusted for age, sex, and iPWC150) was a negative, −0.18 (P < 0.0001). Thus, the two PWC traits are independent of each other, which should be reflected in the underlying biology, as explored in the present study.

Gene-Level GWAS Association Scores

From the SNP-level association P values for iPWC150 or dPWC150, we generated gene-level association scores and P values through the sum of χ squares method in Pascal. Sixteen genes (SEPTIN14, FAM92B, LRGUK, LMO7, CBLB, EDDM3B, HSD17B6, ZNF845, TMEM256, BAZ2A, EPHA7, RNASE6, ATP5B, SNORD59A, SNORD59B, and ANXA6) were associated with iPWC150 at a P value of ≤1 × 10−3, whereas for dPWC150, seven genes were associated at the same P value threshold (RTP1, LBX1, DNAH10, FLJ41350, LIG4, ACTR3BP, and GUCY1A3). Details of the gene-wide association scores are provided in Supplemental Table S2.

Pathway Enrichment Analysis: GWAS

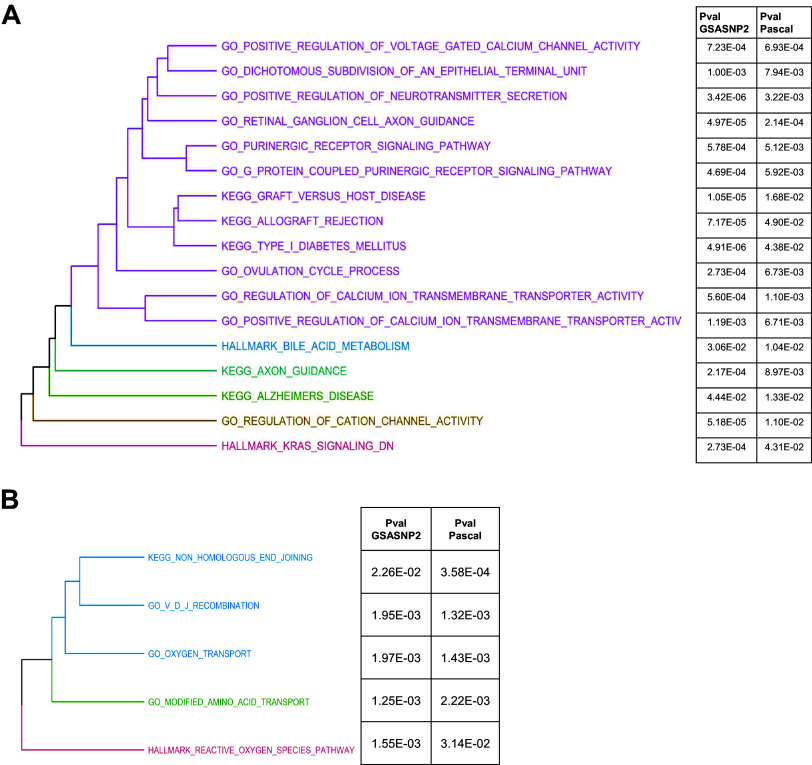

Pathway enrichment analysis was conducted on SNP-level data via GSA-SNP2 and Pascal through query of the KEGG, Hallmark, and GOBP pathway databases from MSigDB. Due to differences in the total number of pathways present in each pathway database and the statistical tests used in each pathway enrichment tool, we adjusted the criteria of pathway significance as follows: nominal P values of <0.05 for KEGG and Hallmark pathways and <0.001 for GOBP pathways for GSA-SNP2 and nominal P values of <0.05 for KEGG and Hallmark and <0.01 for GOBP for Pascal (empirical P value) (full results from all pathway analysis are provided in Supplemental Table S3). Based on these criteria, a total of 123 and 58 pathways were found to be significant for baseline data in GSA-SNP2 and Pascal, respectively, of which 17 pathways were identified by both tools (Poverlap < 2.2 × 10−16 by Fisher’s exact test). For dPWC150 data, 66 and 56 pathways were significant in GSA-SNP2 and Pascal, with 5 pathways called by both (Poverlap < 1.08 × 10−15 by Fisher’s exact test; Fig. 3, A and B). Pathways related to calcium transport and signaling, purinergic signaling, neurotransmitter secretion, and the immune response were among those significantly associated with iPWC150. Pathways related to oxygen and amino acid transport, chromosomal integrity, and reactive oxygen species generation were significantly associated with dPWC150.

Figure 3.

Pathway enrichment analysis based on single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) associations to intrinsic and delta physical working capacity at a heart rate of 150 beats/min (iPWC150 and dPWC150, respectively). A: pathways identified in common by GSASNP2 and Pascal for iPWC150-associated SNPs. The dendrogram was arranged by the extent of gene overlap between pathways. The enrichment P values for each pathway in GSASNP2 and Pascal are indicated in the table to the right of the dendrogram. B: dendrogram of common enriched pathways based on dPWC150-associated SNPs. Pathway P values in GSASNP2 and Pascal are indicated to the right of each pathway. KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes.

Analysis of eQTL

We performed a gene-based association analysis of eQTL by interrogating eQTL datasets related to adipose, skeletal muscle, and whole blood through the algorithm implemented in Eugene (57). For adipose and skeletal muscle, we used eQTL data available from GTEx (48), whereas for whole blood eQTLs, data were examined from three different sources (46–48). By restricting the analysis to gene-based P values ≤ 0.01, where the best independent eQTL (or its proxy) for the gene had a GWAS P value ≤ 0.005, we identified 53 eQTL target genes in iPWC150 and 52 eQTL-associated genes in dPWC150 (Supplemental Table S4). Of these, six genes were eQTL targets in two or more tissues for baseline iPWC150 (PSPHP1, EMC1, PQLC3, RP11-18H21.1, RP11-499P20.2, and RP1-15D23.2), whereas seven genes were multitissue eQTL targets in dPWC150 (C15orf65, SEPTIN2, C14orf79, HAUS4, RP11-616M22.5, TOM1L2, and TPSD1). Several of the eQTL genes with names beginning with RP11 were noncoding (antisense and lincRNAs). The top five eQTL-associated genes from each tissue are shown in Table 2, along with the direction of gene expression and trait association.

Table 2.

Top Eugene-supported trait-associated genes based on adipose, skeletal muscle, and whole blood eQTL data analysis

| Gene | Gene-Based P Value | Best eQTL or Proxy | GWAS Effect Allele | GWAS Effect Size | GWAS P Value | eQTL Effect Allele | eQTL Effect Size | eQTL P Value | eQTL Study | Trait |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RP11-18H21.1 | 1.12E-04 | rs17276450 | A | 0.298 | 1.62E-04 | A | −0.73872 | 1.42E-19 | Adipose (GT) | iPWC150 |

| RNF165 | 1.49E-04 | rs12604983 | G | −0.36 | 1.49E-04 | A | 0.585809 | 5.98E-19 | Adipose (GT) | iPWC150 |

| KCNE3 | 4.20E-04 | rs3853688 | G | −0.271 | 4.20E-04 | G | −0.49713 | 3.21E-25 | Adipose (GT) | iPWC150 |

| RP11-702H23.6 | 4.20E-04 | rs3853688 | G | −0.271 | 4.20E-04 | G | −0.50854 | 9.19E-23 | Adipose (GT) | iPWC150 |

| RP1-15D23.2 | 6.60E-04 | rs704841 | C | 0.281 | 6.60E-04 | C | −0.50184 | 3.15E-15 | Adipose (GT) | iPWC150 |

| PSPHP1 | 6.85E-04 | rs4948075 | A | −0.017 | 1.08E-04 | A | 1.11999 | 8.27E-74 | Muscle (GT) | iPWC150 |

| RP1-15D23.2 | 7.99E-04 | rs12749912 | G | −0.252 | 7.99E-04 | G | 0.392965 | 1.78E-11 | Muscle (GT) | iPWC150 |

| PDSS2 | 1.03E-03 | rs7774958 | C | −0.286 | 1.03E-03 | C | 0.361829 | 3.38E-23 | Muscle (GT) | iPWC150 |

| EMC1 | 1.15E-03 | rs3748759 | C | 0.239 | 1.15E-03 | G | −0.43259 | 7.47E-22 | Muscle (GT) | iPWC150 |

| CHD1L | 1.39E-03 | rs6658826 | A | −0.246 | 1.39E-03 | A | 0.534457 | 2.38E-23 | Muscle (GT) | iPWC150 |

| GALNT3 | 4.34E-04 | rs2304002 | A | −0.257 | 4.34E-04 | A | 0.630615 | 1.61E-23 | Adipose (GT) | dPWC150 |

| DDX25 | 7.59E-04 | rs540225 | C | 0.273 | 7.59E-04 | C | −0.52985 | 6.61E-11 | Adipose (GT) | dPWC150 |

| TOM1L2 | 1.10E-03 | rs3744115 | G | −0.249 | 1.10E-03 | G | 0.25181 | 1.93E-10 | Adipose (GT) | dPWC150 |

| C8orf33 | 1.13E-03 | rs13270948 | A | −0.295 | 1.13E-03 | C | 0.36659 | 1.43E-12 | Adipose (GT) | dPWC150 |

| HAUS4 | 1.28E-03 | rs2295687 | A | −0.247 | 1.28E-03 | G | −0.48066 | 8.33E-17 | Adipose (GT) | dPWC150 |

| HDHD3 | 2.65E-04 | rs16936474 | A | −0.498 | 2.65E-04 | C | −0.67445 | 2.83E-21 | Muscle (GT) | dPWC150 |

| TOM1L2 | 1.10E-03 | rs16960744 | A | −0.249 | 1.10E-03 | T | 0.346506 | 2.08E-20 | Muscle (GT) | dPWC150 |

| HLA-K | 1.21E-03 | rs2517897 | A | −0.378 | 3.09E-04 | A | −0.52585 | 3.10E-10 | Muscle (GT) | dPWC150 |

| HAUS4 | 1.28E-03 | rs2295687 | A | −0.247 | 1.28E-03 | G | −0.3215 | 5.87E-13 | Muscle (GT) | dPWC150 |

| C14orf79 | 1.51E-03 | rs2582577 | T | 0.308 | 1.51E-03 | T | 0.371368 | 7.29E-15 | Muscle (GT) | dPWC150 |

| FLVCR1-AS1 | 3.87E-05 | rs1692189 | A | 0.357 | 3.23E-05 | G | −0.61773 | 2.43E-18 | WB (WA) | dPWC150 |

| ALG1L2 | 6.39E-04 | rs10934906 | T | −0.307 | 6.39E-04 | C | −0.68378 | 4.09E-17 | WB (GT) | dPWC150 |

| HMGXB3 | 7.72E-04 | rs245076 | C | 0.293 | 7.72E-04 | C | −0.18942 | 1.60E-09 | WB (LJ) | dPWC150 |

| EIF2B1 | 9.37E-04 | rs11057379 | G | 0.025 | 4.13E-05 | G | 7.39 | 1.50E-13 | WB (FE) | dPWC150 |

| CSF1R | 1.01E-03 | rs245080 | G | 0.302 | 4.04E-04 | G | 0.338523 | 1.20E-26 | WB (LJ) | dPWC150 |

| RP11-18H21.1 | 1.12E-04 | rs17276450 | A | 0.298 | 1.62E-04 | A | −0.73872 | 1.42E-19 | WB (GT) | iPWC150 |

| RNF165 | 1.49E-04 | rs12604983 | G | −0.36 | 1.49E-04 | A | 0.585809 | 5.98E-19 | WB (GT) | iPWC150 |

| CCDC137 | 2.63E-04 | rs12452184 | T | −0.268 | 2.63E-04 | C | 0.025649 | 6.64E-15 | WB (YA) | iPWC150 |

| KCNE3 | 4.20E-04 | rs3853688 | G | −0.271 | 4.20E-04 | G | −0.49713 | 3.21E-25 | WB (GT) | iPWC150 |

| RP11-702H23.6 | 4.20E-04 | rs3853688 | G | −0.271 | 4.20E-04 | G | −0.50854 | 9.19E-23 | WB (GT) | iPWC150 |

The top five trait-associated genes from each tissue are reported for intrinsic and delta physical working capacity at a heart rate of 150 beats/min (iPWC150 and dPWC150, respectively), sorted by the gene P values. For genes targeted by multiple independent eQTLs, the SNP with the smallest eQTL P value is retained. Column 1, gene name; column 2, Eugene supported gene-trait association P value; column 3, best eQTL SNP (or GWAS proxy) targeting the gene; column 4, GWAS effect allele; column 5, GWAS effect size; column 6, GWAS P value; column 7, eQTL effect allele; column 8, eQTL effect size; column 9, eQTL P value; column 10, public eQTL database [WB, whole blood; GT, GTEx; LJ, Lloyd Jones (CAGE); FE, Fehrmann; WA, Walsh; YA, Yao]; column 11, GWAS used (iPWC150 or dPWC150).

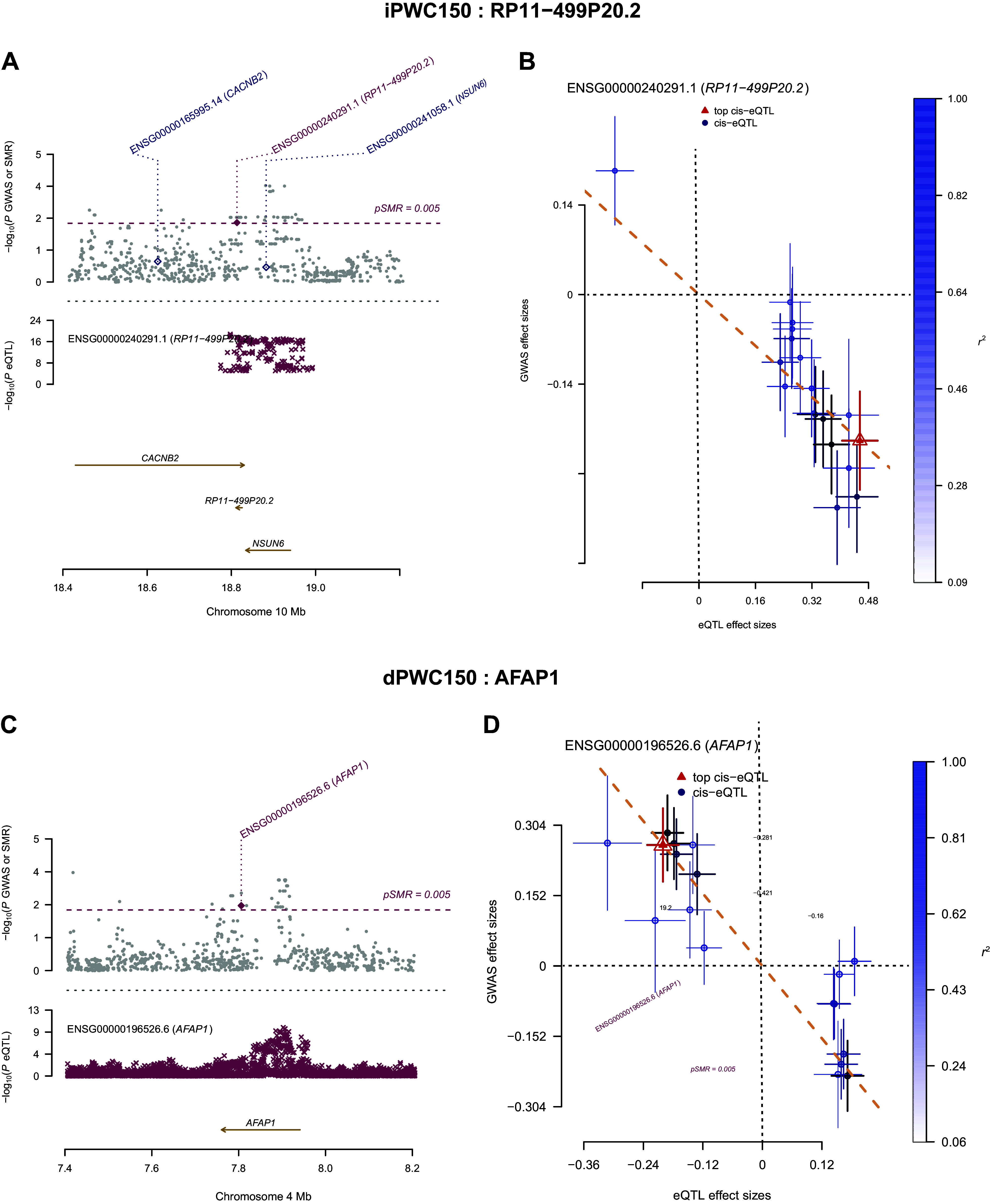

Analysis of Pleiotropy in eQTL SNPs by SMR

We next examined if the identified eQTLs also showed evidence of pleiotropy (same SNP responsible for influencing gene expression as well as association to iPWC150 or dPWC150) contrasted to linkage (2 linked SNPs independently affecting gene expression and trait association). The analysis used a Mendelian randomization-based approach developed in the SMR program. SMR analysis was restricted to eQTL data from whole blood, SAT, VAT, and skeletal muscle datasets, as described in methods. A total of 47 and 55 genes were found to be significant in SMR analysis in at least one eQTL database (PSMR ≤ 0.005) for the iPWC150 and dPWC150 data, respectively, with strong evidence for pleiotropy (PHEIDI > 0.05; Supplemental Table S5). A subset of these genes was found to be eQTLs in more than one tissue type including skeletal muscle (RP11-499P20.2 and CHD1L for iPWC150 and SEPTIN2, C14orf79, GALNT3, HAUS4, TOM1L2, and TPSD1 for dPWC150), as shown in Table 3. Of these, the RP11-499P20.2 and SEPTIN 2 genes were significant eQTL targets in all four tissue types examined in SMR (whole blood, SAT, VAT, and muscle), whereas others, such as the actin filament-associated protein 1 (AFAP1) gene, were only significant in skeletal muscle eQTLs. Locus and effect plots for RP11-499P20.2 and AFAP1 in skeletal muscle are shown in Fig. 4, A and B. In these plots, the top panel shows SNP P values for the relevant GWAS experiments (iPWC150 or dPWC150) and the bottom plots show the eQTL P value distribution of the same SNPs from the relevant eQTL database, along with genomic features around the cis-eQTLs.

Table 3.

Top SMR hits from PWC150 GWAS and skeletal muscle eQTLs

| Gene | topSNP | topSNP_pos | GWAS Effect Allele | GWAS Other Allele | Effect Allele Frequency | Effect Size (GWAS) | P value (GWAS) | Effect Size (eQTL) | P value (eQTL) | Effect Size (SMR) | P value (SMR) | P value (HEIDI) | eQTL Database | Trait |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHD1L | rs2353986 | 1:146821869 | C | T | 0.66 | 0.25 | 1.39E-03 | −0.43 | 4.97E-20 | −0.58 | 2.55E-03 | 8.53E-01 | MUS (G) | iPWC150 |

| CHD1L | rs10793652 | 1:146707543 | A | G | 0.51 | 0.25 | 8.12E-04 | 0.31 | 3.97E-23 | 0.80 | 1.50E-03 | 7.35E-01 | WB (G) | iPWC150 |

| DEFB124 | rs717064 | 20:30066356 | T | G | 0.14 | 0.37 | 2.01E-03 | 0.83 | 5.67E-27 | 0.44 | 2.96E-03 | 9.37E-01 | MUS (G) | iPWC150 |

| EMC1 | rs12062540 | 1:19529204 | G | A | 0.40 | 0.24 | 1.16E-03 | −0.32 | 2.16E-21 | −0.75 | 1.99E-03 | 1.00E-01 | MUS (G) | iPWC150 |

| EMC1 | rs709683 | 1:19565344 | G | C | 0.32 | 0.22 | 3.26E-03 | −0.42 | 2.67E-32 | −0.52 | 4.25E-03 | 3.90E-01 | SAT (G) | iPWC150 |

| ENTPD1-AS1 | rs3088372 | 10:97927802 | A | T | 0.11 | 0.38 | 1.36E-03 | 0.42 | 1.57E-09 | 0.91 | 4.58E-03 | 1.92E-01 | MUS (G) | iPWC150 |

| MTMR6 | rs1129861 | 13:25909954 | A | G | 0.07 | −0.35 | 3.65E-03 | 0.42 | 3.59E-28 | −0.83 | 4.94E-03 | 4.59E-01 | MUS (G) | iPWC150 |

| PDSS2 | rs7774958 | 6:107493418 | C | T | 0.29 | −0.29 | 1.03E-03 | 0.32 | 1.19E-25 | −0.90 | 1.71E-03 | 3.43E-01 | MUS (G) | iPWC150 |

| RP11-499P20.2 | rs10741091 | 10:18802307 | G | C | 0.38 | −0.23 | 2.99E-03 | 0.45 | 1.47E-19 | −0.51 | 4.72E-03 | 5.35E-01 | MUS (G) | iPWC150 |

| RP11-499P20.2 | rs10764582 | 10:18823279 | A | T | 0.39 | −0.23 | 2.99E-03 | 0.69 | 1.55E-42 | −0.33 | 3.66E-03 | 1.66E-01 | SAT (G) | iPWC150 |

| RP11-499P20.2 | rs7088091 | 10:18804094 | C | T | 0.38 | −0.23 | 2.99E-03 | 0.74 | 5.17E-31 | −0.31 | 3.97E-03 | 1.21E-01 | VAT (G) | iPWC150 |

| RP11-499P20.2 | rs11015312 | 10:18932953 | A | G | 0.38 | −0.23 | 2.99E-03 | 0.69 | 8.17E-33 | −0.33 | 3.91E-03 | 2.36E-01 | WB (G) | iPWC150 |

| RP13-467H17.1 | rs4567083 | 8:143488279 | T | C | 0.84 | 0.30 | 2.39E-03 | 0.47 | 3.21E-14 | 0.63 | 4.64E-03 | 2.66E-01 | MUS (G) | iPWC150 |

| RP13-467H17.1 | rs6583620 | 8:143450095 | C | G | 0.13 | −0.35 | 5.27E-04 | −0.57 | 2.39E-10 | 0.60 | 2.45E-03 | 4.48E-01 | SAT (G) | iPWC150 |

| ZNF845 | rs8113071 | 19:53834333 | G | T | 0.55 | 0.25 | 9.33E-04 | 0.34 | 5.01E-16 | 0.73 | 2.28E-03 | 4.53E-01 | MUS (G) | iPWC150 |

| AFAP1 | rs13127935 | 4:7913961 | T | C | 0.36 | 0.26 | 1.01E-03 | −0.20 | 2.64E-10 | −1.31 | 3.41E-03 | 1.21E-01 | MUS (G) | dPWC150 |

| C14orf79 | rs2582574 | 14:105454529 | G | A | 0.21 | 0.30 | 1.52E-03 | 0.39 | 4.50E-20 | 0.77 | 2.65E-03 | 9.12E-01 | MUS (G) | dPWC150 |

| C14orf79 | rs2582577 | 14:105450112 | T | C | 0.22 | 0.31 | 1.51E-03 | 0.51 | 1.81E-24 | 0.60 | 2.43E-03 | 3.50E-01 | SAT (G) | dPWC150 |

| C14orf79 | rs2582574 | 14:105454529 | G | A | 0.21 | 0.30 | 1.52E-03 | 0.35 | 6.90E-14 | 0.85 | 3.41E-03 | 8.94E-01 | VAT (G) | dPWC150 |

| GALNT3 | rs2304002 | 2:166714095 | A | G | 0.43 | −0.26 | 4.34E-04 | 0.50 | 1.85E-23 | −0.52 | 9.00E-04 | 2.58E-01 | MUS (G) | dPWC150 |

| GALNT3 | rs2304002 | 2:166714095 | A | G | 0.43 | −0.26 | 4.34E-04 | 0.62 | 1.13E-35 | −0.42 | 7.04E-04 | 2.92E-01 | SAT (G) | dPWC150 |

| GALNT3 | rs2304002 | 2:166714095 | A | G | 0.43 | −0.26 | 4.34E-04 | 0.41 | 1.90E-16 | −0.62 | 1.21E-03 | 1.88E-01 | VAT (G) | dPWC150 |

| HAUS4 | rs4981455 | 14:23422453 | G | A | 0.53 | 0.25 | 1.28E-03 | −0.35 | 4.51E-27 | −0.71 | 2.11E-03 | 4.93E-01 | MUS (G) | dPWC150 |

| HAUS4 | rs4981455 | 14:23422453 | G | A | 0.53 | 0.25 | 1.28E-03 | −0.70 | 1.25E-80 | −0.35 | 1.56E-03 | 3.73E-01 | SAT (G) | dPWC150 |

| HAUS4 | rs4981455 | 14:23422453 | G | A | 0.53 | 0.25 | 1.28E-03 | −0.56 | 2.36E-34 | −0.44 | 1.92E-03 | 3.87E-01 | VAT (G) | dPWC150 |

| IFI27L1 | rs882269 | 14:94566559 | T | C | 0.56 | −0.23 | 2.69E-03 | 0.50 | 7.04E-49 | −0.46 | 3.42E-03 | 7.34E-01 | MUS (G) | dPWC150 |

| MED23 | rs3756784 | 6:131950233 | G | T | 0.21 | 0.34 | 1.11E-03 | −0.27 | 4.10E-11 | −1.28 | 3.47E-03 | 8.06E-01 | MUS (G) | dPWC150 |

| N4BP2 | rs7674515 | 4:40064563 | T | C | 0.08 | −0.48 | 2.57E-03 | 0.88 | 1.42E-15 | −0.54 | 4.90E-03 | 4.63E-02 | MUS (G) | dPWC150 |

| SEPTIN2 | rs11681497 | 2:242344333 | G | A | 0.09 | 0.49 | 2.13E-04 | 0.35 | 1.47E-14 | 1.41 | 8.86E-04 | 1.47E-01 | WB(LJ) | dPWC150 |

| SEPTIN2 | rs2074771 | 2:242350944 | G | A | 0.09 | 0.48 | 3.41E-04 | 1.17 | 7.26E-139 | 0.41 | 3.70E-04 | 1.40E-01 | WB(LJ) | dPWC150 |

| SEPTIN2 | rs2074771 | 2:242350944 | G | A | 0.09 | 0.48 | 3.41E-04 | 1.26 | 5.99E-162 | 0.38 | 3.63E-04 | 9.19E-02 | WB(LJ) | dPWC150 |

| SEPTIN2 | rs7601738 | 2:242375813 | T | A | 0.09 | 0.49 | 2.13E-04 | 0.68 | 4.11E-45 | 0.73 | 3.62E-04 | 2.82E-01 | MUS (G) | dPWC150 |

| SEPTIN2 | rs757978 | 2:242371101 | T | C | 0.09 | 0.49 | 2.13E-04 | 0.77 | 1.21E-53 | 0.64 | 3.36E-04 | 9.97E-02 | SAT (G) | dPWC150 |

| SEPTIN2 | rs7601738 | 2:242375813 | T | A | 0.09 | 0.49 | 2.13E-04 | 0.71 | 1.67E-41 | 0.70 | 3.76E-04 | 2.03E-01 | VAT (G) | dPWC150 |

| SEPTIN2 | rs7601738 | 2:242375813 | T | A | 0.09 | 0.49 | 2.13E-04 | 0.49 | 4.23E-31 | 1.02 | 4.43E-04 | 2.32E-02 | WB (G) | dPWC150 |

| SEPTIN2 | rs7601738 | 2:242375813 | T | A | 0.09 | 0.49 | 2.13E-04 | 1.03 | 6.42E-294 | 0.48 | 2.44E-04 | 1.16E-01 | WB(W) | dPWC150 |

| TOM1L2 | rs8066560 | 17:17728043 | G | A | 0.58 | 0.25 | 1.26E-03 | 0.35 | 3.10E-34 | 0.70 | 1.76E-03 | 8.46E-01 | MUS (G) | dPWC150 |

| TOM1L2 | rs7501812 | 17:17750907 | A | G | 0.56 | 0.25 | 1.10E-03 | 0.28 | 7.75E-19 | 0.88 | 2.12E-03 | 6.85E-01 | SAT (G) | dPWC150 |

| TPSD1 | rs2745084 | 16:1294025 | G | A | 0.52 | 0.22 | 3.60E-03 | 0.77 | 2.47E-54 | 0.29 | 4.26E-03 | 1.04E-01 | MUS (G) | dPWC150 |

| TPSD1 | rs2745084 | 16:1294025 | G | A | 0.52 | 0.22 | 3.60E-03 | 0.97 | 2.73E-69 | 0.23 | 4.12E-03 | 1.02E-01 | SAT (G) | dPWC150 |

| VPS37C | rs471718 | 11:60913487 | C | A | 0.55 | 0.25 | 1.44E-03 | −0.17 | 1.58E-13 | −1.46 | 3.48E-03 | 7.54E-01 | MUS (G) | dPWC150 |

| WISP1 | rs16904845 | 8:134199776 | C | T | 0.34 | −0.27 | 1.36E-03 | 0.34 | 4.14E-09 | −0.80 | 4.92E-03 | 5.56E-01 | MUS (G) | dPWC150 |

Genes with summary data-based Mendelian randomization (SMR) P values of ≤5E − 03 and HEIDI P values of >0.05 are shown. Column 1, gene name; column 2, top instrumental single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) used in SMR; column 3, chromosome and position of top SNP (hg19); column 4, effect allele; column 5, noneffect allele; column 6, effect allele frequency; column 7, SNP effect size in genome-wide association study (GWAS); column 8, SNP GWAS P value; column 9, SNP effect size in expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) data; column 10, SNP eQTL P value; column 11, SNP effect size in SMR; column 12, SNP SMR P value; column 13, SNP HEIDI P value; column 14, eQTL tissue (MUS, skeletal muscle; SAT, subcutaneous adipose tissue; VAT, visceral adipose tissue; WB, whole blood; G, GTEx; W, Westra eQTL data; LJ, Lloyd Jones (CAGE); column 15, GWAS study.

Figure 4.

Summary data-based Mendelian randomization (SMR)-based expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) analysis in skeletal muscle. A: SMR-based locus plot shown for RP11-499P20.2 lncRNA, as an example. Top: −log10(P values) of the single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) near the RP11-499P20.2 locus from the genome-wide association study (GWAS) analysis of intrinsic physical working capacity at a heart rate of 150 beats/min (iPWC150). Red and blue diamonds represent −log10(P values) from the SMR tests for associations of gene expression with iPWC150. Probes showing pleiotropy (not rejected by the HEIDI test) are indicated by solid diamonds. Bottom: plot showing –log10(P values) of the SNP association for gene expression probe ENSG00000185324.17 (tagging RP11-499P20.2) from the GTEx skeletal muscle eQTL database and the genomic features around the SMR significant SNP. B: comparison of effect sizes in GWAS and eQTL datasets for probe ENSG00000185324.17 (red triangle). eQTLs around the top cis-eQTLs were positively associated with increased expression of RP11-499P20.2 (x-axis) and inversely associated with iPWC150 levels (y-axis), suggesting that increased lncRNA expression may regulate one or more genes associated with iPWC150. The color bar to the right shows the level of correlation of eQTLs with the top cis-eQTL. C: SMR-based locus plot for the actin filament-associated protein 1 (AFAP1) gene. Plot elements are same as for the locus plot for RP11-499P20.2. D: comparison of effect sizes in GWAS and eQTL for the AFAP1 probe. AFAP1-associated cis-eQTLs were negatively associated with both skeletal muscle AFAP1 gene expression and delta intrinsic physical working capacity at a heart rate of 150 beats/min (dPWC150) levels. Plot elements are the same as for effect size comparisons with RP11-499P20.2-associated SNPs.

Based on the results from multiple analyses of the GWAS data, including gene-level association scores for iPWC150 or dPWC150, pathway enrichment analysis, gene-based eQTL analysis, and SMR analysis, we identified 213 candidate genes (130 and 83 genes from iPWC150 and dPWC150 analyses, respectively) for further querying in knockout mouse models and examination for genetic association with cardiovascular and muscle phenotypes (available in HERITAGE participants).

Analysis of Gene Expression in Skeletal Muscle Biopsies

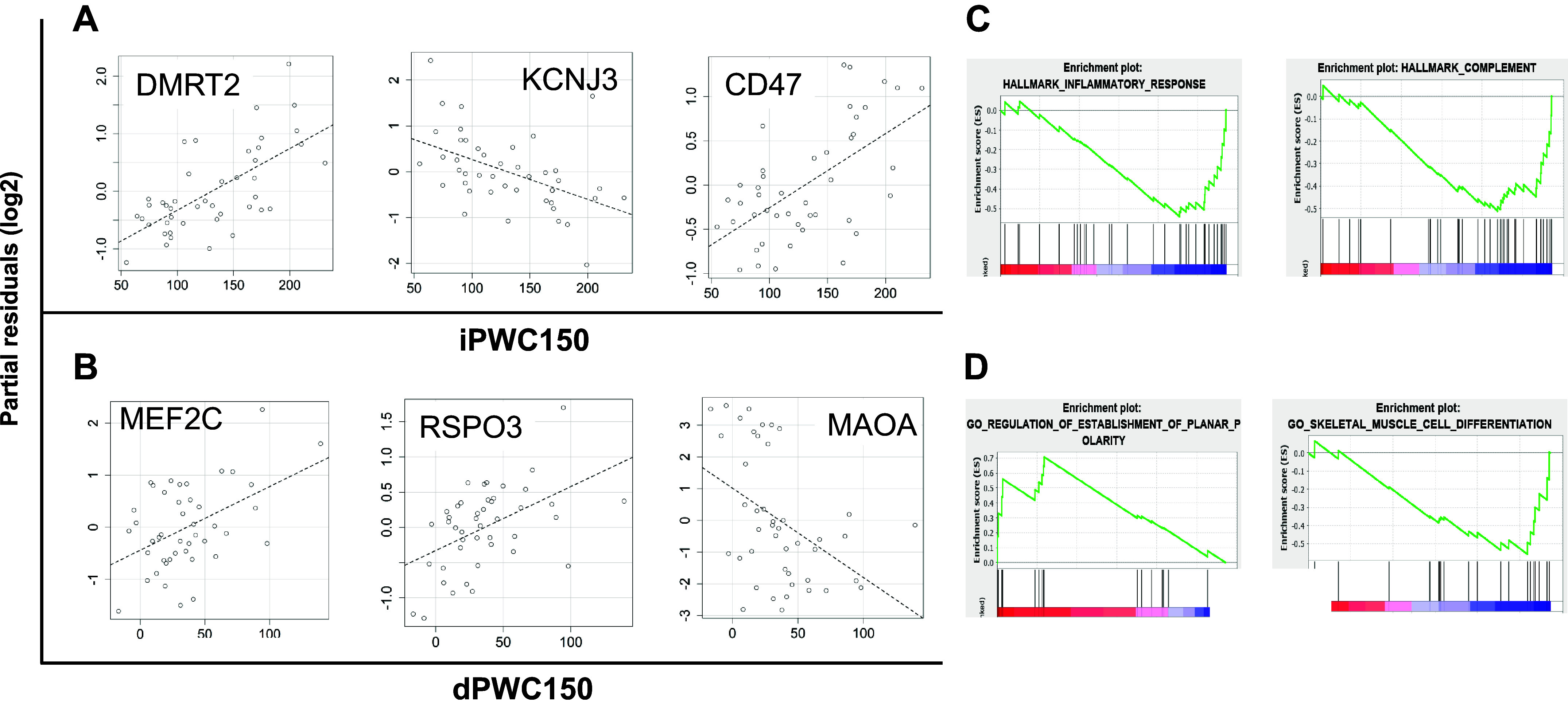

Whole genome expression profiling data of vastus lateralis muscle biopsies from a subset of 44 genotyped participants was analyzed via linear models to identify genes that were transcriptionally correlated with iPWC150 or dPWC150 levels, after adjustments for age, sex, body mass index, and scan date. For dPWC150 analysis, an additional adjustment for iPWC150 levels was also made. Based on a regression P value of ≤0.05 and absolute t statistic of ≥2.0, 52 and 123 genes were significantly associated with iPWC150 and dPWC150 levels, respectively. No overlap was noted among the significant genes from the two phenotypes. Partial residual plots for selected significant genes associated with iPWC150 and dPWC150 are shown in Fig. 5, A and B. The full results of the linear modeling analysis for iPWC150 and dPWC150 data are provided in Supplemental Table S6.

Figure 5.

Transcriptomics analysis of intrinsic and delta physical working capacity at a heart rate of 150 beats/min (iPWC150 and dPWC150, respectively) associations. A: partial residual plots of log2 gene expression versus iPWC150 levels for selected significantly associated genes. The name of the gene is indicated at the top of each plot. iPWC150 values are plotted on the x-axis, and the partial residual scores are plotted on the y-axis. The dashed line represents the line of best fit from linear regression analysis. B: partial residual plots for selected genes significantly associated with dPWC150. Plots are constructed in exactly the same way as described for iPWC150. C and D: enrichment plots of selected pathways from Gene Set Enrichment Analysis of gene expression association with iPWC150 or dPWC150, respectively. Pathway names are listed at the top of each plot. The enrichment of upregulated or downregulated genes in a given pathway is shown in the enrichment plots (negative enrichment scores in the plot imply downregulation of gene expression with iPWC150 or dPWC150 levels, and vice versa).

Pathway Analysis: Transcriptomics

We next conducted pathway enrichment analysis by using the gene expression regression coefficients for iPWC150 or dPWC150 in the GSEA framework and by querying three independent pathway databases from MSigDB (KEGG, Hallmark, and GOBP). A total of 30 and 8 pathways were significantly enriched with genes associated with iPWC150 and dPWC150, respectively (FDR ≤ 0.1). Notably, pathways related to proinflammatory signaling (e.g., chemokine production and the inflammatory response), complement gene expression, and extracellular matrix-receptor interactions were downregulated in the iPWC150-associated genes. The skeletal muscle cell differentiation pathway was enriched in genes negatively associated with dPWC150, whereas increased dPWC150 was positively associated with the planar cell polarity pathway. Figure 5, C and D, shows the GSEA enrichment plots for some top-scoring pathways from iPWC150 and dPWC150 analysis. Full details of pathway analysis results are provided in Supplemental Table S7.

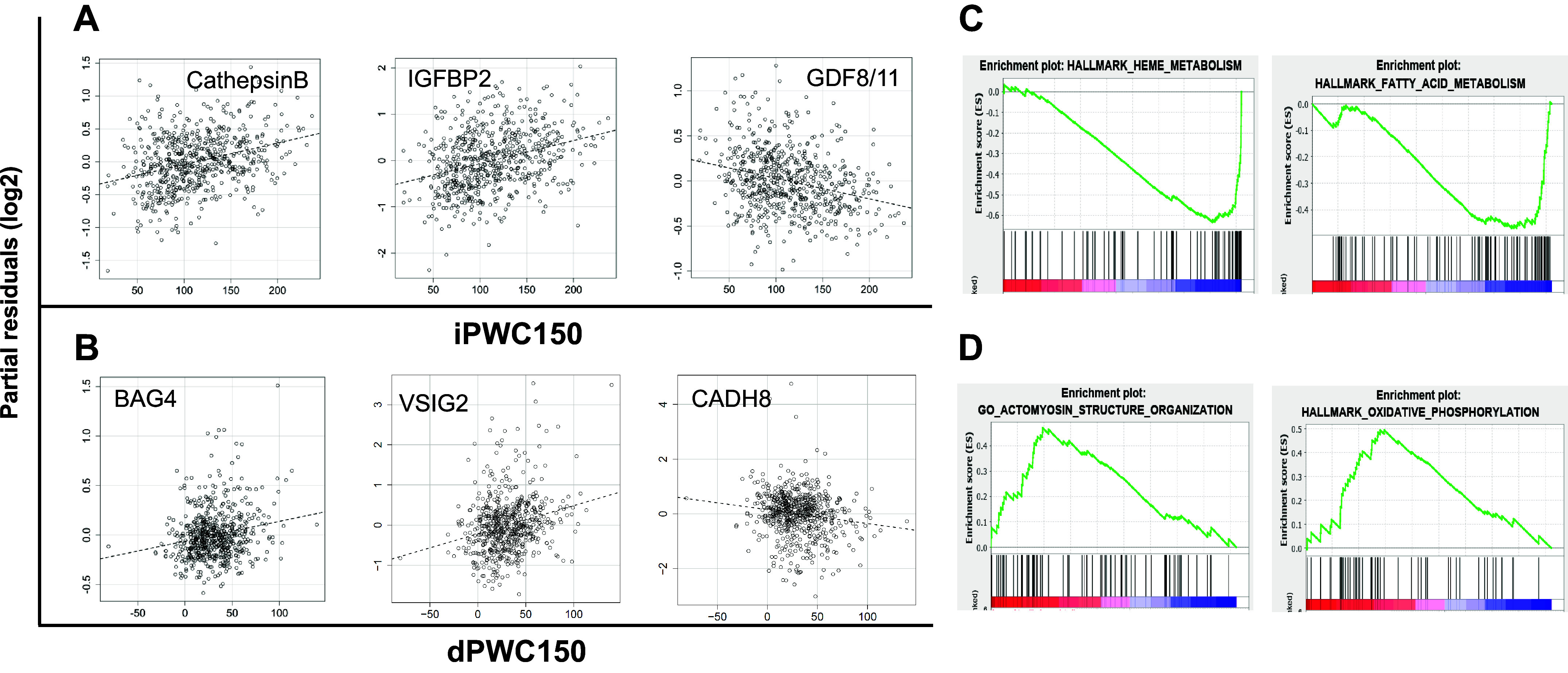

Analysis of Plasma Protein Levels

Plasma protein expression data from 408 genotyped participants were analyzed via linear models to identify proteins that were associated with adjusted iPWC150 or dPWC150 levels, after adjustments for age, sex, and body mass index. Based on a regression P value of ≤1 × 10−4 and absolute t statistic of ≥2.0, 29 and 36 proteins were significantly associated with baseline and dPWC150 levels, respectively. Of the 29 iPWC150-associated proteins, 19 were annotated as “secreted” in UniprotKB, whereas 9 of the 36 dPWC150-associated proteins were also secreted (Supplemental Fig. S1). Again, no overlap was noted among the significant proteins from the two phenotypes. Partial residual plots for selected significant proteins are shown in Fig. 6, A and B. Details of the linear modeling analysis for iPWC150 and dPWC150 data are provided in Supplemental Table S8.

Figure 6.

Proteomics analysis of intrinsic and delta physical working capacity at a heart rate of 150 beats/min (iPWC150 and dPWC150, respectively) associations. A: partial residual plots of log2 protein expression versus iPWC150 levels for selected significantly associated proteins. The name of the protein is indicated at the top of each plot. iPWC150 values are plotted on the x-axis, and partial residual scores are plotted on the y-axis. The dashed line represents the line of best fit from linear regression analysis. B: partial residual plots for selected proteins significantly associated with dPWC150. Plots are constructed in exactly the same way as described for iPWC150. C and D: enrichment plots of selected pathways from Gene Set Enrichment Analysis of protein expression association with iPWC150 or dPWC150, respectively. Pathway names are listed at the top of each plot. The enrichment of upregulated or downregulated genes in a given pathway is depicted in the enrichment plots.

Pathway Analysis: Proteomics

Pathway enrichment analysis of the proteomics data was conducted via GSEA using the protein expression regression coefficients for iPWC150 or dPWC150 as input. For GSEA, 18 and 235 pathways were identified at FDR < 0.1 from a combined analysis of KEGG, Hallmark, and GOBP pathways on iPWC150- and dPWC150-associated proteomics data, respectively. Four pathways overlapped between the iPWC150- and dPWC150-associated pathways. For iPWC150, strong downregulation was noted for fatty acid- and heme metabolism-related pathways, whereas pathways related to mTOR signaling, oxidative phosphorylation, and actinomyosin structure formation were upregulated among the dPWC150-associated pathways. GSEA enrichment plots for some top-scoring pathways from iPWC150 and dPWC150 analysis are shown in Fig. 6, C and D. Full details of pathway analysis results are provided in Supplemental Table S9.

Analysis of Plasma Metabolite Levels

Data for 187 targeted plasma metabolites in 408 subjects were analyzed via linear regression to identify metabolites associated with adjusted (age, sex, and body mass index) iPWC150 or dPWC150. A total of 25 and 49 metabolites were found to be nominally associated with baseline and dPWC150, respectively (P < 0.05, absolute t > 2), with two metabolites, acetylcholine and niacinamide, identified in both sets (Supplemental Table S10). Notably, three metabolites involved in ketone body metabolism (acetoacetate, 2-hydroxybutyrate, and 3-hydroxybutyrate) were all negatively associated with iPWC150 (Fig. 7A). For dPWC150, a strong positive association was observed for several purine nucleotides including AMP, ADP, and ATP as well as for aspartate, glutamate, and carnitine conjugates (Fig. 7B). The amino acid derivative carnitine and several medium- and long-chain fatty acyl-carnitines (C6-, C7-, and C16-acylcarnitines) were also positively associated with dPWC150. Although we did not carry out a general pathway enrichment analysis with metabolite data (due to the small number of metabolites tested), we mapped a subset of the dPWC150-associated metabolites onto two KEGG pathway diagrams to visualize the potential impact of such changes on pathway activity, as shown in Fig. 7C.

Figure 7.

Metabolomics analysis of intrinsic and delta physical working capacity at a heart rate of 150 beats/min (iPWC150 and dPWC150, respectively) associations. A: partial residual plots of selected significantly associated metabolites to iPWC150. The name of the metabolite is indicated at the top of each plot. iPWC150 values are plotted on the x-axis, and partial residuals for relevant metabolites are shown on the y-axis. The dashed line represents the line of best fit from linear regression analysis. B: partial residual plots for selected metabolites significantly associated with dPWC150. Plots are constructed in exactly the same way as described for iPWC150. C: visualization of metabolites significantly associated to dPWC150 in selected Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathways. Positive associations are shown in red, and negative associations are shown in blue.

Analysis of Knockout Mouse Phenotypes

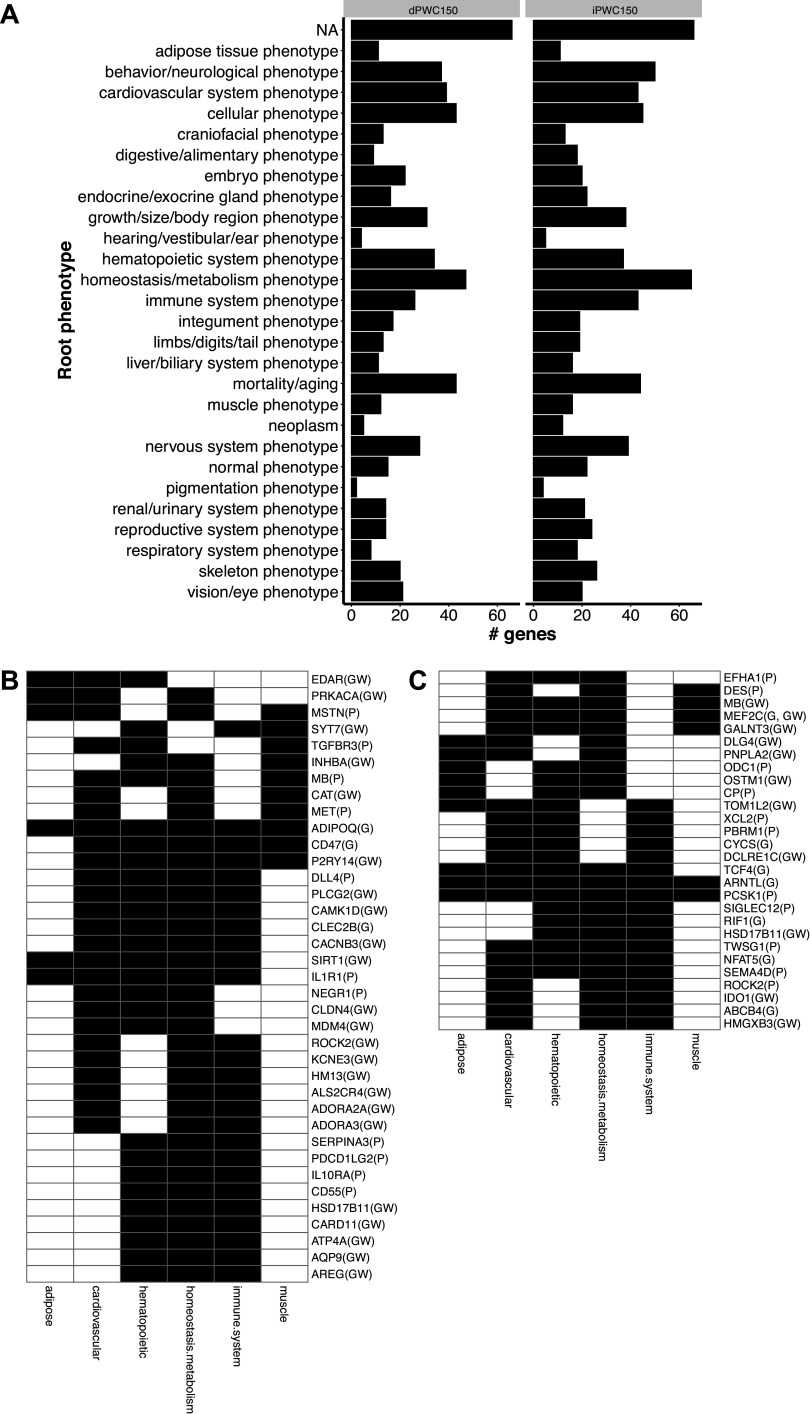

A total of 322 candidate genes were retained from the combined analyses of GWAS, transcriptomic, and proteomic data from iPWC150 and dPWC150 and queried for knockout mouse phenotypes from MGI. The numbers of dPWC150-associated genes were 85 from GWAS, 29 from transcriptomics, and 37 from proteomics analyses. From this list, knockout mouse phenotypes were available for 117 iPWC150-associated genes and 90 dPWC150-associated genes. The list of all genes selected from GWAS, genomics, and proteomics is provided in Supplemental Table S11. Notably, the myoglobin (MB) and ROCK2 genes were identified in both GWAS and proteomics analysis, whereas the myocyte enhancer factor 2 C (MEF2C) gene was identified in GWAS as well as transcriptomics analysis. The individual knockout phenotypes obtained from MGI for each gene were further aggregated into broader categories (“root phenotypes”) reflecting the organ systems affected (e.g., cardiovascular, muscle, nervous system, etc.) (Fig. 8A). The largest category (NA) consisted of genes for which no knockout mouse data are available, followed by organ systems such as the cardiovascular system, behavior/neurological system, or homeostasis/metabolism. From this list, we focused on a group of six root phenotypes including adipose, cardiovascular, hematopoietic, homeostasis/metabolism, immune, and muscle due to their greater potential relevance for submaximal indicators of cardiorespiratory fitness (Fig. 8B).

Figure 8.

Phenotypic consequences of candidate intrinsic and delta physical working capacity at a heart rate of 150 beats/min (iPWC150 and dPWC150, respectively) associated gene knockouts in the Mouse Genome Informatics (MGI) database. A: genes selected from genome-wide association study (GWAS), transcriptomics, and proteomics approaches were used to query the MGI database for phenotypes arising from targeted gene knockouts or gene trap models. The left and right graphs show results for dPWC150- and iPWC150-associated genes, respectively. The number of top-level phenotypes (root phenotypes) impacted are plotted. The root phenotype categories are indicated on the y-axis, and the total number of genes observed for each category are shown on the x-axis (genes without knockout mouse data are indicated as NA). B and C: heatmap depicting genes with ≥3 root phenotypes in the MGI database. B: iPWC150-associated genes. C: dPWC150-associated genes. Genes are listed in rows, and root phenotypes are listed in columns. The presence of a root phenotype in a gene knockout is indicated by shaded cells. The source of the genes is indicated next to the gene names in parentheses [GWAS (GW), transcriptomics (G), and proteomics (P)].

For both iPWC150- and dPWC150-selected genes, the largest number of root phenotypes were related to homeostasis/metabolism, followed by cardiovascular phenotypes. Among the iPWC150-selected genes, ADIPOQ, SIRT1, CD47, P2RY14, IL1R1, DLL4, MB, CACNB3, CLEC2B, MSTN, PLCG2, and CAMK1D affected four or more of the six root phenotypes. Similarly, the dPWC150-selected genes, ARNTL, PCSK1, TCF4, MEF2C, MB, TOM1L2, TWSG1, NFAT5, GALNT3, and SEMA4D also displayed knockout effects in four or more root phenotypes. For each selected root phenotype, we then investigated the individual phenotypes for the candidate genes of interest (Supplemental Figs. S2 and S3). For iPWC150-associated genes, many adipose tissue-related phenotypes were observed in myostatin (MSTN/GDF8) and type 1 interleukin 1 receptor (IL1R1) knockout mice. Neuropilin 1 (NRP1) and delta-like 4 homolog (DLL4) gene knockouts displayed the largest number of cardiovascular phenotypes. Hematopoietic phenotypes were dominated by caspase recruitment domain family member 11 (CARD11) and interleukin 2 receptor-β (IL2RB) genes, whereas knockout of adiponectin (ADIPOQ) showed the largest homeostasis/metabolism-related phenotypes. Immune phenotypes were most prominent in CARD11 knockout mice, and a significant number of muscle-specific effects were observed for knockouts in MSTN and MET proto-oncogene genes.

A similar analysis with dPWC150-associated gene candidates revealed the largest number of adipose phenotypes in patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing 2 gene (PNPLA2) knockouts, whereas the largest number of cardiovascular phenotypes was observed for knockout of the MEF2C gene. Hematopoietic phenotypes were observed in knockout of the DNA cross-link repair 1 C (DCLRE1C) gene, whereas arylhydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator-like (ARNTL) and PNPLA2 gene knockouts displayed the largest number of homeostasis/metabolism phenotypes. The DNA ligase 4 (LIG4) gene knockout showed the greatest effects on immune-related phenotypes, whereas the desmin (DES) gene knockout was associated with the greatest number of muscle-specific phenotypes.

SNP-Trait Associations With Cardiovascular and Muscle-Specific Phenotypes

In addition to phenotype queries in knockout mouse models, we also examined whether SNPs mapping to the query genes showed evidence of association with resting and exercise-related cardiovascular and muscle-specific traits measured in HERITAGE participants. In addition, eQTL SNPs of interest identified from Eugene and SMR analysis were also included. A total of 29 cardiovascular and muscle traits were examined for the SNP association analyses. The analysis identified 1,963 SNPs mapping to 161 iPWC150-associated genes that were nominally associated (P < 0.01) with at least one of the cardiovascular and muscle traits examined. Similarly, 937 SNPs mapping to 131 dPWC150-associated genes were nominally associated with one or more examined traits. Figure 9, A and B, shows the trait-association results for a selection of the genes associated with five or more traits. From the iPWC150-associated genes, PLCG2, CAMK1D, RNF165, DLG2, PDE4D, and SHISA6 displayed significant associations with ≥10 cardiovascular traits, whereas CAMK1D, DLG2, PDE4D, DMRT2, UNC5C, SMOC1, and EPHA7 displayed significant associations with ≥10 muscle traits. For dPWC150, genes such as MEF2C, MRPS17, LIG4, UNC13C, GUCY1A3, RPS14P3, CSMD2, MCTP2, CTD-2324F15.2, and ZBTB20 showed associations with ≥5 cardiovascular traits, whereas LIG4, CSMD2, MCTP2, MB, UNC13C, and CTD-2324F15.2 also showed significant associations with ≥7 muscle traits. The list of the 29 examined traits and the significant SNP association results are provided in Supplemental Table S12.

Figure 9.

Single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP)-trait association analysis for cardiovascular and muscle traits. A: heatmap of gene-trait associations. Genes are shown in rows, and traits are shown in columns. Heatmaps are color coded by the maximum of the negative log P values obtained for SNP-trait associations for all SNPs mapping to a gene (P < 0.01). For multiple significant SNPs mapping to a gene, the lowest SNP-trait association P value is used to represent the gene association P value. Only genes with association to ≥5 traits (out of 29 traits) are shown in the heatmap. Left: intrinsic physical working capacity at a heart rate of 150 beats/min (iPWC150); right: delta physical working capacity at a heart rate of 150 beats/min (dPWC150). B: an example of SNP-trait association for multiple SNPs in the myocyte enhancer factor 2 C (MEF2C) gene. SNP genotypes are plotted on the x-axis and average trait values (±SE) are shown on the y-axis in each plot.

Prioritization of Candidate Genes

We took advantage of knockout mouse phenotypes and human SNP-trait association analyses to prioritize a panel of candidate genes. The goal was to use phenotypic corroboration as a tool to identify genes that may be causally associated with iPWC150 or dPWC150, instead of relying solely on the statistical associations observed in the genomics, transcriptomics, or proteomics analyses. However, as knockout mouse phenotype data were not available for all candidate genes, we used two different approaches to gene prioritization. In the first case (phenotype-focused prioritization), genes showing evidence for effects in both knockout mouse phenotypes and human cardiovascular and muscle-specific phenotypes were selected, based on the extent of the phenotypes affected. In the second case (eQTL-focused prioritization), genes that were significant eQTLs in skeletal muscle and displayed significant muscle SNP-trait associations were selected. For phenotype-focused prioritization, we retained candidate genes with greater than or equal to five significant (P < 0.01) SNP-trait associations and greater than or equal to three knockout mouse root phenotypes. This resulted in 13 candidate genes for iPWC150 associations (CAMK1D, PLCG2, CARD11, P2RY14, EDAR, HSD17B11, TGFBR3, NEGR1, IL1R1, CAT, CD47, ADORA3, and AREG) and 6 candidate genes for dPWC150 associations (MB, TCF4, CP, CYCS, DCLRE1C, and MEF2C). For eQTL-focused prioritization, candidate genes with a significant muscle eQTL association (P ≤ 0.01) and greater than or equal to five significant (P < 0.01) SNP-trait associations were retained, resulting in two candidate genes for iPWC150 (ENTPD1-AS1 and RP13-467H17.1) and five candidate genes for dPWC150 [HAUS4, TPSD1, AFAP1, N4BP2, and CCN4(WISP1)]. The list of the prioritized candidate genes is shown in Table 4, along with a brief description of gene function. The combined results from the knockout mouse phenotype experiments and SNP-trait association experiments for all candidate genes are provided in Supplemental Table S13.

Table 4.

Prioritization of candidate genes based on “phenotype-focused” or “eQTL-focused” gene selection

| Gene | Transcriptomics (P < 0.05, Abs. β >=0.008) | Proteomics | GWAS_Genescore (P < 0.01) | GWAS_Common_Pathway | eQTL_Eugene_WB | eQTL_Eugene_SAT/VAT | eQTL_Eugene_Muscle | eQTL_SMR_WB | eQTL_SMR_SAT/VAT | eQTL_SMR_Muscle | KO_Mouse_Adipose Phenotypes | KO_Mouse_Cardiovascular Phenotypes | KO_Mouse_Hematopoietic Phenotypes | KO_Mouse_Homeostasis/Metabolism Phenotypes | KO_Mouse_Immune Phenotypes | KO_Mouse_Muscle | Total_Count_KO_Mouse_Phenotypes | SNP_CVtraits_Association | SNP_Muscletraits_Association | Total_Count_SNP_Trait_Association | Biological Function | Trait | Basis of selection |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADORA3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 5 | 5 | Receptor for adenosine, has cardioprotective function during cardiac ischemia | iPWC150 | Phenotype |

| AREG | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 5 | Ligand of the EGF receptor/EGFR. Autocrine growth factor as well as a mitogen for a broad range of target cells | iPWC150 | Phenotype |

| CAMK1D | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 11 | 14 | 25 | Regulates calcium-mediated granulocyte function and basal dendritic growth of hippocampal neurons | iPWC150 | Phenotype |

| CARD11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 6 | 9 | 15 | Involved in the costimulatory signal essential for T-cell receptor (TCR)-mediated T-cell activation | iPWC150 | Phenotype |

| CAT | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 6 | Key antioxidant enzyme, protects cells from the toxic effects of hydrogen peroxide. | iPWC150 | Phenotype |

| CD47 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 5 | Role in cell adhesion and as a “marker of self” on red blood cells to prevent their elimination by macrophages | iPWC150 | Phenotype |

| EDAR | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 8 | 2 | 10 | Member of the tumor necrosis factor receptor family, mediates the activation of NF-κ-B and JNK | iPWC150 | Phenotype |

| ENTPD1-AS1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 7 | lncRNA class, antisense to ENTPD1 | iPWC150 | eQTL |

| HSD17B11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 10 | May participate in androgen metabolism during steroidogenesis | iPWC150 | Phenotype |

| IL1R1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 6 | Receptor for IL1A, IL1B and IL1RN mediating activation of NF-κ-B, MAPK and other pathways | iPWC150 | Phenotype |