Abstract

Drug-induced acute kidney injury (AKI), especially from exposure to antibiotics, has a high prevalence secondary to their frequent prescription. Typically, drug-induced AKI results from acute tubular necrosis or acute interstitial nephritis. While some risk factors for the development of AKI in individuals treated with antibiotics are modifiable, others such as concomitant drug therapies to treat comorbidities, age, and pre-existing chronic kidney disease are not modifiable. As such, there is an urgent need to identify strategies to reduce the risk of AKI in individuals requiring antibiotic therapy. Natural products, especially those rich in active constituents possessing antioxidant properties are an attractive option to mitigate AKI risk. Given that mitochondrial dysfunction precedes AKI and natural products can restore mitochondrial health and counter the oxidative stress secondary to mitochondrial damage investigating their utility warrants further attention. The following review summarizes the available preclinical and clinical evidence that provides a foundation for future study.

Keywords: Natural products, Acute kidney injury, Oxidative stress, Antibiotics

Introduction

Globally, 13.3 million cases of acute kidney injury (AKI) are diagnosed per year [1,2]. Drugs are responsible for up to 26% of AKI cases, and antibiotics are implicated in approximately 50% of these events [3]. The use of antibiotics in hospitalized patients is common, with roughly 60% of hospitalized patients receiving at least one antibiotic during their hospital course. Hospitalized patients frequently require multiple antibiotics raising the risk of AKI [4–6]. Some risk factors for antibiotic-induced AKI are modifiable, but many are not, including advanced age, obesity, heart failure, hypertension, and diabetes. Moreover, while concomitant nephrotoxic drugs are modifiable, many are essential for clinical management.

Given the frequency of individuals managed with antibiotics, the identification of therapies to reduce iatrogenesis is critical. Natural products are an attractive option for the prevention of AKI given their over-the-counter availability, patient willingness to consume, and safety profiles. From a mechanistic perspective, a variety of natural products may target the inciting factors leading to AKI. Oxidative stress is thought to be a key driver of antibiotic-induced AKI, and various natural products have antioxidant properties, including activation of nuclear factor-erythroid factor 2-related factor 2 (NRF2) and the master regulator of antioxidant response. This review summarizes the available evidence supporting natural products as reno-protective agents.

Proposed antibiotic-induced nephrotoxicity pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of antibiotic-induced nephrotoxicity (Table 1) can generally be separated into two main categories of injury, acute tubular necrosis (ATN) and acute interstitial nephritis (AIN) (Figure 1). ATN is precipitated by the exposure of the proximal tubule to toxic substances. This exposure can occur in several ways, including apical drug transport or basolateral (peritubular) drug transport into the proximal tubular cells [7]. Although the intrinsic toxicity of antibiotics against proximal tubule cells is not entirely known, mitochondrial injury is commonly cited as a potential cause because mitochondria are highly abundant in the kidney and work as the primary energy source for kidney cell function [8,9]. Changes to kidney mitochondrial integrity are often seen prior to the clinical manifestation of AKI [9]. A proposed mechanism involves the uptake of antibiotics into lysosomes, which subsequently leak into the cell cytoplasm and cause injury to multiple organelles, including the mitochondria [10]. During normal homeostasis, the mitochondrion is responsible for producing reactive oxygen species, including superoxide, hydroxyl, and hydrogen peroxide radicals. However, these reactive oxygen species can induce cellular apoptosis, lipid peroxidation, and calcium imbalance if not protected by mitochondrial antioxidant mechanisms [11]. Ischemic reperfusion injury (IRI) is also implicated in aminoglycoside-associated injury via worsened reperfusion cellular energetics [12]. IRI ultimately recruits proinflammatory cytokines and increases the production of reactive oxygen species that lead to lipid peroxidation to further damage renal tubule cells [13].

Table 1.

| Drug class | Select medications within drug class | Proposedpathophysiology | Proposed mechanism of drug injury |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aminoglycosides | Gentamicin, tobramycin, neomycin, amikacin, streptomycin | ATN | Mitochondrial toxicity and subsequent free radical generation in addition to decreased proximal tubule protein synthesis |

| Beta lactams (penicillins, cephalosporins, carbapenems) | Cephaloridine, cephaloglycin, imipenem | ATN | Damage to mitochondrial transport and substrate uptake through the production of oxidative products |

| Rifamycin | Rifampin | AIN + ATN | Formation of drug-antibody complexes that deposit in either the tubular epithelium or interstitium |

| Sulfonamides | Sulfamethoxazole | AIN | Immune-mediated hypersensitivity and cytotoxic T-cell injury |

| Glycopeptide | Vancomycin | ATN + AIN | Oxidative stress and generation of ROS in proximal tubule cells |

Abbreviations: AIN = acute interstitial nephritis; ATN = acute tubular necrosis; ROS = reactive oxygen species.

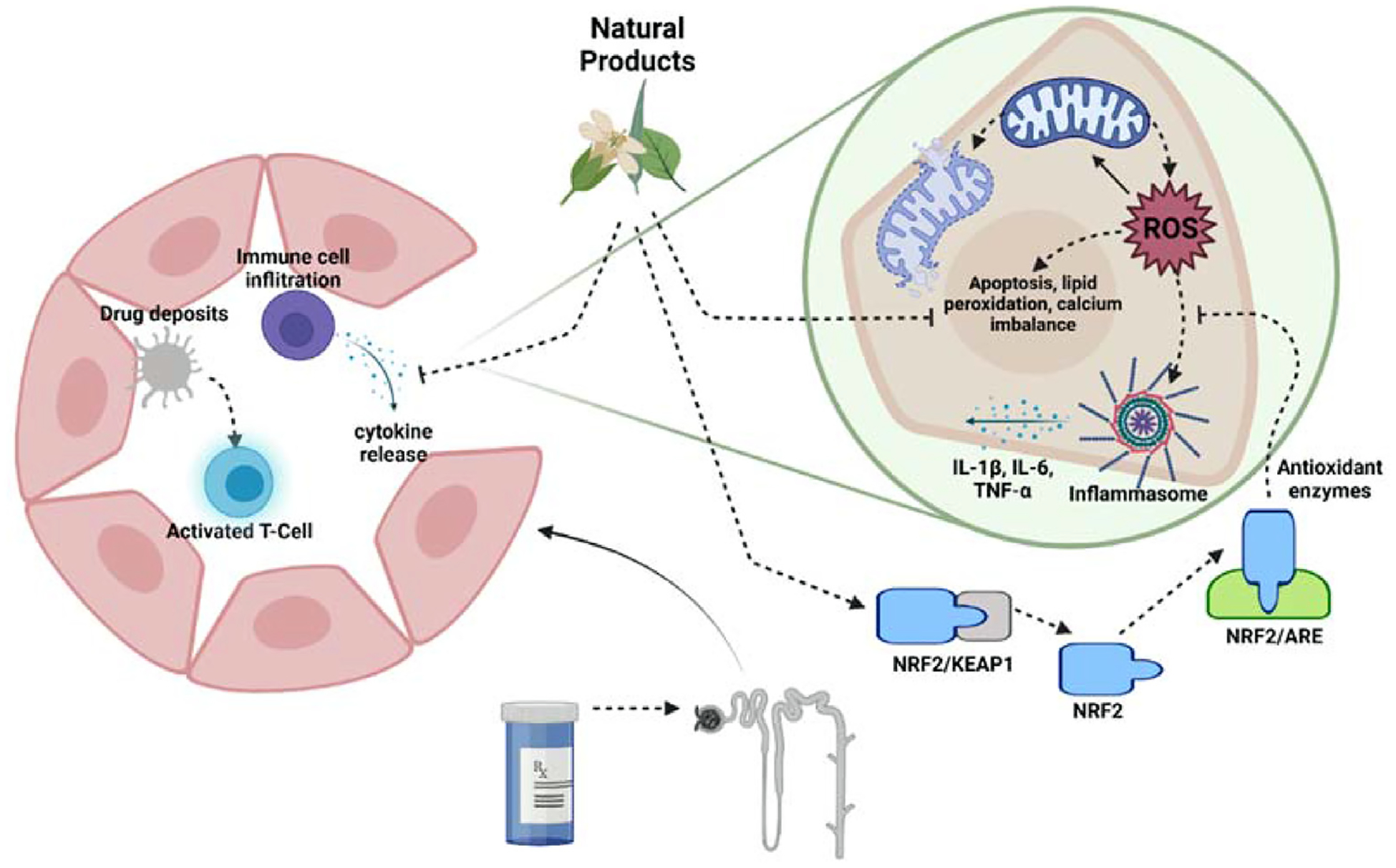

Figure 1.

Medications may cause acute kidney injury by a variety of mechanisms. The pathophysiology can be categorized into two main categories – acute interstitial nephritis (AIN) and acute tubular necrosis (ATN). Right panel: AIN results secondary to T-cell mediated hypersensitivity. Toxin deposits in the interstitium bind to proteins forming haptens and activating the immune cascade. Macrophages present the antigens to T-cells resulting in their activation. In turn, the infiltrating activated immune cells release chemokines and cytokines resulting in damage to the nephron. Left panel: ATN is precipitated by exposure of the proximal tubule cells to a toxin. This exposure triggers mitochondrial stress, production of reactive oxidative species (ROS), activation of the inflammasome, and chemokine and cytokine release. Ultimately, mitochondrial dysfunction, cell apoptosis, lipid peroxidation, and calcium imbalance lead to the manifestation as acute kidney injury. Natural products may mitigate the cascade of events through NRF2 activation and restoration of mitochondrial health.

AIN is believed to be a T-cell-mediated hypersensitivity reaction [14]. Drugs within the kidney can become immunogenic through the binding to specific proteins forming haptens, acting directly as antigens, or forming neo-antigens. These drugs are believed to subsequently deposit in the interstitium. Following the immunogenicity of these molecules, renal dendritic cells and macrophages present these antigens to T-cells activating them. The effector T-cells increase the production of chemokines and cause the localization of inflammatory cells. The hypersensitivity reaction typically results in renal infiltration with lymphocytes, macrophages, and other immune cells, causing nephron damage [15]. Furthermore, the long-term activation of this process can lead to fibroblast activation through tumor growth factor (TGF)-β, causing fibrosis and chronic kidney disease [16]. When comparing the two potential mechanisms of toxicity, natural products may be more effective at preventing AKI resulting from the ATN variety since many of these compounds support mitochondrial health through antioxidative properties – a key inciting factor in ATN.

Mechanism of action of natural products in the context of AKI

Natural products are commonly used to treat various ailments, although their mechanisms of action are not always completely understood. Traditionally, natural products are divided into categories based on their molecular structure. These products can also be organized by their mechanism, which involves their action on cellular transport, DNA damage, apoptosis, oxidative stress, inflammation, and autophagy [17]. Due to the oxidative stress induced by nephrotoxic drugs during kidney injury, there is reason to believe that certain natural products with action against oxidative stress may prove beneficial.

Flavonoids can be widely found in many plants, consumed primarily through fruits, vegetables, and medicinal plants [18]. The protective effect of flavonoids against oxidative stress can be attributed to their ability to decrease free radicals. Some flavonoids can directly scavenge . Other flavonoids achieve this effect by the potential inhibition of xanthine oxidase [19]. Xanthine oxidase is present in a variety of tissues, including the kidney. Due to its high output of superoxide anions, the inhibition of xanthine oxidase results in a similar decrease in free radical production [20]. There are data suggesting that flavonoids can suppress cyclooxygenase, lipoxygenase, mitochondrial succinoxidase, and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide + hydrogen (NADH) oxidase enzymes which also play a role in reactive species production [21]. Total flavonoids have also been discovered to decrease levels of inflammatory markers, such malondialdehyde (MDA), as well as upregulate levels of silent information regulator factor 2-related enzyme 1 (SIRT1) and nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor-2 (NRF2), which play integral roles in the regulation of antioxidant genes in kidney injury caused by IRI13. Saponins are another class of natural products commonly found within traditional medicines [22]. Specific isolated triterpene saponins were tested as free radical scavengers and were shown to have activity against superoxide, hydroxyl, and hydrogen peroxide free radicals [22,23]. Certain alkaloids found within natural medicines have also been documented to have antioxidant characteristics. Berberine, an isoquinoline alkaloid found within several plant species, including Berberis vulgaris, Berberis thunbergii, and Berberis aquifolium, was shown to decrease the expression of enzymes of 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (4-HNE), a lipid peroxidation product that propagates oxidative stress [24]. Collectively, natural products possess properties that may alleviate oxidative stress and protect the kidney from antibiotic-induced kidney injury. Several preclinical studies have investigated natural products and are summarized below.

Preclinical evidence

Drug-induced nephrotoxicity is a result of various factors, such as the innate toxicity profile of a compound, patient characteristics, and the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic characteristics of a drug [25]. Several antibiotics carry an inherent risk of nephrotoxicity and are cleared through the kidney, presenting a toxicity risk.

Gentamicin is an aminoglycoside that is commonly used in combination with other antibiotics to treat serious gram-negative bacillary or gram-positive coccal infections [26]. However, gentamicin is also a well-known nephrotoxic agent proposed to cause tubular, glomerular, and vascular effects on the kidney [27]. Furthermore, gentamicin has also been proposed to cause kidney damage through oxidative stress [28], [29] which has been supported by various studies using experimental natural antioxidants such as trans-resveratrol [30], rutin [31], vitamins E and C [32] to prevent gentamicin-induced kidney damage. Another proposed mechanism involves the upregulation of myo-inositol oxygenase (MIOX), which may augment the production of lipoxygenase-12 (ALOX-12) and subsequently 12-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (12-HETE). Both ALOX-12 and 12-HETE increase inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6. Furthermore, in MIOX-overexpressed transgenic mice, there was increased production of 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE), a major biomarker of reactive oxygen species and lipid hydroperoxidation. Usage of ML355, an experimental ALOX-12 inhibitor showed decreased expression of tubular apoptosis and inflammatory mediators, as well as decreasing albumin excretion demonstrating functional improvement [33]. While not investigated for kidney protection, there are natural products (i.e., baicalein and Traumeel) that inhibit ALOX-12 or interrupt the arachidonic acid pathway [34,35].

Vancomycin is a glycopeptide antibiotic effective against gram-positive infections, and it is hypothesized to cause AKI with prolonged and higher doses [36–38]. Though the exact mechanism of vancomycin-induced AKI is not clearly defined, preclinical data suggest that vancomycin can induce oxidative stress in the proximal tubule, causing acute renal damage [78,79]. The reactive oxygen species generated by vancomycin compromise renal cellular membrane integrity by inducing lipid peroxidation and cause poly [ADP-ribose] polymerase 1 (PARP-1) overactivity from DNA damage, jointly leading to cellular apoptosis and acute renal tubule cell damage. The leakage of proteases from lysosomes damaged by reactive oxygen species may also instigate cell death [39]. Well-established antioxidants such as caffeic acid phenethyl ester (CAPE), vitamin C, vitamin E, and N-acetylcysteine have all been studied in animal models to assess the reno-protective capacity against vancomycin-induced AKI with promising results [40].

Colistin, a polymyxin E, is used to treat infections caused by multidrug-resistant (MDR) gram-negative bacteria [41,42]. Nevertheless, the high rate of colistin-associated nephrotoxicity reported in the recent meta-analysis has limited its use in clinical practice [43]. The mechanism of colistin-associated nephrotoxicity is still not clearly identified. It was hypothesized that colistin directly interacts with tubular epithelial cell membrane which leads to increased membrane permeability and eventually cell death [44,45]. However, recent research proposes that the oxidative stress caused by intracellularly accumulated colistin may be one of the critical factors related to colistin-associated nephrotoxicity [44]. Several preclinical studies support the efficacy of natural products with antioxidant properties to reduce the risk of kidney injury, such as ascorbate [46], alpha-tocopherol [47], melatonin [48], and black garlic [49] with promising results.

Various plant and fruit extracts have been studied in preclinical studies for their reno-protective effects against antibiotic-induced nephrotoxicity. The results of select preclinical studies are summarized in Table 2 [49–68].

Table 2.

Select preclinical studies evaluating natural products for the prevention of antibiotic-associated acute kidney injury.

| Antibiotic | Study (Author, Year) | Natural products | Rationale | Active constituents | Animal model and exposure | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gentamicin | Uzun-Goren et al., 2022 | Curcumin | Curcumin is an antioxidant and has been evaluated in numerous studies. | Curcumin, demethoxycurcumin, and bisdemethoxycurcumin | Male Wistar rats exposed to gentamicin 80 mg/kg/day intraperitoneal for 10 days following curcurmin. Curcumin 100 mg/kg/day orally for 15 days or control. |

Curcumin attenuated nephrotoxicity by suppressing p38 MAPK and NFκβ and activating NRF2. |

| Laorodphun et al., 2022 | Curcumin | Curcumin acts as antioxidant to inhibit free radical generation and scavenges reactive oxygen species. | Curcumin, demethoxycurcumin, and bisdemethoxycurcumin | Male Sprague-Dawley rats exposed to gentamicin 100 mg/kg/day for 15 days. Curcumin (100, 200, and 300 mg/kg/day) concomitantly or control for 15 days. |

Pre-treatment with curcumin resulted in reversed nephrotoxicity hallmarks (serum creatinine, blood urea nitrogen, and augmented creatinine clearance) and normalized markers of oxidative stress (malondialdehyde), and increased antioxidant molecules (superoxide dismutase, glutathione). | |

| Sarwar et al., 2022 | Water Spinach and red grape | Red grape and water spinach contain compounds necessary to scavenge free radical and promote renal tubule regeneration. | Polyphenolic compounds | Female Wistar albino rats exposed to gentamicin 80 mg/kg/day for 7 days. Water spinach (20 g/rat/day) or red grape (5 mL/rat/day) or control for 7 days. |

Administration of red grape and water spinach has been shown to ameliorate gentamicin-induced nephrotoxicity through histological and biochemical findings and improving kidney function by decreasing uremic toxins (serum creatinine, uric acid). | |

| Hassanein et al., 2021 | Umbelliferone | Umbelliferone (UBF) is a coumarin derivative that has potent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity. | Coumarin phenolic compound | Adult male Wistar rats exposed to gentamicin 100 mg/kg intraperitoneal for 8 days. UMB 50 mg/kg for 7 days prior to gentamicin and continued concomitantly for 8 days or control. |

Administration of UMB prior to and concomitantly with gentamicin decreased serum creatinine and urea, decreased expression of ERK1/ERK2, TLR-4, and p38 MAPK renal proteins and suppression of NF-κB-p65/NLRP-3, and JAK1/STAT-3. | |

| Ersegkin et al., 2020 | Ferulic acid | Ferulic acid has antioxidant properties, as well as protective effect in various kidney diseases. | Phenolic acid | Female Wistar albino rats exposed to gentamicin 80 mg/kg/day intraperitoneally for 8 days. Ferulic acid 50 mg/kg orally given concomitantly for8 days or control. |

Administration of ferulic acid was shown to decrease urea, creatinine, malondialdehyde, advanced protein products, IL-6, and TNF-α. | |

| Beshay et al., 2020 | Resveratrol | Resveratrol is widely known compound with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties and has been previously studied for its nephroprotective ability. | Polyphenol | Male albino mice exposed to gentamicin 225 mg/kg intraperitoneal for 15 days. Resveratrol 50 mg/kg intraperitoneal for 7 days prior to gentamicin and continued concomitantly for 15 days or control. |

Administration of resveratrol was shown to decrease serum creatinine, BUN, and malondialdehyde and increase GSH and glutathione catalase activity. | |

| Salama et al., 2018 | Troxerutin | Troxerutin found in coffee/tea and several vegetables shown to have antioxidant properties. | Flavonoid | Male Wistar rats exposed to gentamicin 50 mg/kg intraperitoneal for 15 days. Troxerutin 50 mg/kg/day orally for 15 days concomitantly or control. |

Co-administration with troxerutin was shown to significantly improve renal function (increased GFR and decreased urinary albumin) and decreased nephrotoxic findings (albumin to creatinine ratio, serum creatinine, and BUN), renal tubule injury markers (KIM-1), and inflammatory cytokines (IL-10, IL-6, TNF- α). | |

| Mahmoud et al., 2017 | Kiwifruit | Kiwifruit alleviates oxidative stress and gentamicin induces nephrotoxicity by forming free radicals. | Flavonoids, polyphenols, serotonin, and vitamins C and E | Male CD1 albino mice exposed to gentamicin100 intramuscular 100 mg/day for 10 days. Kiwifruit 70 mg/day for 10 days or control. |

Co-administration of kiwifruit with gentamicin had reduced improved histochemical findings and near a complete recovery. | |

| Moreira Galdino et al., 2017 | Rudgea viburnoides | Rudgea viburnoides was historically used for multiple purposes medically (hypotensive, blood depurative, anti-rheumatic, diuretic) including kidney pain. | Tannins, flavonoids, triterpenes, sterols, and saponins | Adult male Wistar rats exposed to gentamicin 80 mg/kg twice daily for 5 days. Plant extract 50 or 200 mg/kg twice daily for 7 days or control. |

Administration of Rudgea viburnoides plant extract decreased the serum creatinine and polyuria, reversed gentamicin-induced proteinuria, and altered the morphology of the kidneys in comparison with the control arms. | |

| Jose et al., 2016 | Coconut inflorescence sap powder | Coconut inflorescence sap powder is used traditionally for multiple medical conditions as it is proposed to work as a detoxifying agent. | Endogenous antioxidants (exact compounds unknown) contains carbohydrates, minerals, vitamins, and amino acids | Adult male Wistar rats exposed to gentamicin 80 mg/kg for 16 days. Coconut inflorescence sap powder 20 mg/kg for 16 days or control. |

Administration of Coconut inflorescence sap powder was associated with a significant improvement in all biochemical parameters (antioxidant enzymes, GSH, creatinine, uric acid, urea, inflammatory markers, and lipid peroxidation) suggesting reduced of kidney injury. | |

| Aldahmash et al., 2016 | Propolis | Propolis has been studied in multiple medical conditions and is a substance formed from plants that consist mostly of antioxidating agents. | Eight different flavonoids have been reported | Swiss albino mice exposed to gentamicin 80 mg/kg for 7 days. Propolis 500 mg/kg for 7 days or control. |

Coadministration of propolis decreased BUN and significant histological findings, however, there was an insignificant difference in serum creatinine levels to the control. | |

| Cekmen et al., 2013 | Pomegranate extract | Pomegranate extract displays antioxidant properties, and gentamicin-induced kidney injury is proposed to facilitate through reactive oxygen species. | Vitamin C, flavonoids (anthocyanins) | Adult male Wistar albino rats exposed to gentamicin 100 mg/kg for 14 days. Pomegranate extract 100 μ/L for 14 days or control. |

Administration of pomegranate extract resulted in a statistically significant lower serum creatinine and BUN along with a significantly greater GSH and reduced kidney damage via analysis of histologic parameters. | |

| Hussain et al., 2012 | Solanum xanthocarpum fruit extract | Solanum xanthocarpum fruit extract is used traditionally for multiple medical conditions. | Steroidal alkaloids, flavonoids, and glycosides | Wistar rats were exposed to gentamicin 100 mg/kg for 8 days. Solanum xanthocarpum fruit extract 200 or 400 mg/kg for 8 days or control. |

Administration of the Solanum xanthocarpum fruit extract significantly lowered serum creatinine, BUN, and renal lipid peroxidation along with an increase in renal antioxidants. Histological parameters were concurrent with these findings. | |

| Hsu et al., 2011 | Sesame oil | Iodinated contrast used with aminoglycosides works synergistically to cause kidney damage through oxidative stress and sesame oil works as an antioxidant. | Potent antioxidants | Sprague-Dawley rats exposed to gentamicin 100 mg/kg/day for 5 days with or without a single dose of 4 ml/kg contrast. Sesame oil 0.5 ml/kg as a single dose or control. |

Administration of sesame oil showed statistical significance in preventing the rise in BUN and serum creatinine levels. This was also evidence in histological and oxidative findings. | |

| Shirwaikar et al., 2004 | Aerva lanata | Aerva lanata was historically used for kidney protection in a multitude of ailments. | Flavonoids, alkaloids, steroids, polysaccharides, tannins, saponins | Adult male Wistar albino rats exposed to gentamicin 40 mg/kg for 13 days or cisplatin 5 mg/kg once. Ethanol extract of Aerva lanata 75, 150 or 300 mg/kg for 5 days or control for cisplatin group or for 10 days or control for gentamicin group. |

A dose-dependent reduction of acute tubular necrosis was seen when administering ethanol extract treatment (displayed by the BUN and serum creatinine). In the preventative groups, there was a reversal of some of the damage as seen with the BUN and serum creatinine. | |

| Colistin | Worakajit et al., 2022 | Panduratin A | Panduratin A has shown to attenuate oxidative damage and inhibit activity against lipid peroxidation. | A bioactive flavonoid | C57BL/6 male mice exposed to colistin 15 mg/kg for 7 days. Panduratin A 2.5 mg/kg or 25 mg/kg for 7 days or control. |

Administration of Panduratin A attenuated colistin nephrotoxic effects which was demonstrated through BUN, and histologic findings. |

| Dumludag et al., 2022 | Silymarin | Historically used to treat liver and gallbladder diseases along with poisoning due to its known hepatoprotective effects. Proposed to have Anti-inflammatory, antifibrotic and anti-apoptotic effects. | silibinin, isosilybinin, taxifolin, silychristine, dihydrosilibinin and silydianine | Sprague–Dawley male rats exposed to colistin 750,000 IU/kg/day for 7 days. Silymarin100 mg/kg/day for 7 days or control. |

Administration of silymarin displayed improvement in tubular necrosis and a significant increase in antioxidant capacity, as seen through glutathione peroxidase and superoxide dismutase levels, when co-administered with colistin. | |

| Wang et al., 2020 | 7-Hydroxycoumarin | Previous experimental studies that demonstrated protective effects of 7-hydroxycoumarin (7-HC) against renal injury caused by cisplatin and methotrexate | Coumarin phenolic compound | Adult Kunming mice exposed to colistin 15 mg/kg/day for 7 days. 7-hydroxycoumarin 50 mg/kg/day for 7 days or control. |

Administration of 7-HC decreased malondialdehyde and increased superoxide dismutase and catalase activities. 7-HC attenuated oxidative stress by promoting NRF2 signaling. | |

| Colistin Lee et al., 2019 | Aged black garlic | Aged black garlic contains constituents that possess antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties that could help ameliorate kidney injury from colistin. | Phytochemical compounds (phenolic compounds, flavonoids, pyruvate, and thiosulfate), and the major organosulfur compounds (SAC and S- allylmercaptocysteine) | Male Sprague-Dawley rats exposed to colistin 10 mg/kg for 6 days. 1% Aged black garlic (100 μL) or control for 6 days. |

Administration of aged black garlic reduced the serum creatinine and BUN in a statistically significant manner, and histological findings were consistent with less renal damage. | |

| Ghlissi et al., 2018 | Vitamins E and C | Known antioxidant activity which can work synergistically together. | Vitamin E and C | Male Wistar rats exposed to colistin methane sulfonate 450,000 IU/kg/day for 7 days. 100 mg/kg/day of Vitamin C plus 100 mg/kg of Vitamin E or control for 7 days. |

Coadministration of vitamins E and C improved histopathological damage and restored all biochemical parameters, such as superoxide dismutase, catalase, and glutathione peroxidase. | |

| Vancomycin | Qu et al., 2020 | Chlorogenic acid | Chlorogenic acid has been studied and shown to have antioxidant effects through free radical scavenging. | Phenolic compound | Rats were exposed to vancomycin 200 mg/kg intraperitoneal twice daily for 7 days. Chlorogenic acid 150 mg/kg orally 2 h prior to vancomycin dosing for 7 days or control. |

Administration of chlorogenic acid prior to vancomycin resulted in decreased malondialdehyde and nitric oxide, decreased pro-inflammatory mediators, and prevented the decrease of glutathione reductase, peroxidase, and catalase. |

Abbreviations: BUN = blood urea nitrogen, GFR = glomerular filtration rate, GSH = glutathione, IL = interleukin, JAK = Janus kinase, KIM-1 = kidney injury molecule-1, MAPK = mitogen-activated protein kinases, NFkβ = nuclear factor kappa β, NRF2 = nuclear factor-erythroid factor 2-related factor 2, STAT = signal transducer and activator of transcription protein, TLR-4 = toll-like receptor 4, TNF-α= tumor necrosis factor α

Clinical evidence

As described in the previous sections, numerous preclinical studies evaluate the reno-protective effects of the natural products against antibiotic-induced kidney injury. However, there are few published human studies that translate the findings of preclinical evidence. A small randomized controlled clinical trial (n = 28) investigated the effects of ascorbic acid on the risk of kidney injury secondary to colistin and did not identify any benefits [69]. The small sample of this study makes drawing conclusions difficult. In another randomized controlled trial enrolling 179 subjects receiving vancomycin with 84 receiving concomitant N-acetylcysteine (NAC), individuals receiving NAC had significantly improved serum creatinine and creatinine clearance but did not find statistically significant differences in the incidence of AKI between groups [70]. Similarly, a small matched-group interventional study (30 vitamin E + vancomycin vs. 60 vancomycin alone) reported that exposure to vitamin E significantly reduced the incidence of AKI with improvements in serum blood urea nitrogen (BUN), while other markers of kidney functions such as serum creatinine, creatinine clearance, and urine output were not significantly improved [71]. Lastly, a recent retrospective cohort study (101 melatonin + vancomycin vs. 202 vancomycin alone) evaluating the reno-protective effects of melatonin against vancomycin-induced nephrotoxicity found that melatonin was associated with a reduced incidence of AKI in hospitalized patients after accounting for confounding in a multivariable analysis [72]. Collectively, the available data are derived from small samples and limited in the assessment strategies of kidney injury. Confirmation in large randomized controlled trials is essential to identify the utility of natural products in preventing AKI in the clinical setting. An ongoing clinical trial investigating melatonin for the prevention of vancomycin-associated kidney injury will provide additional evidence on the prospect of using natural products as reno-protective agents (NCT05084196).

Challenges and concerns with natural products

Numerous preclinical studies suggest that natural products may have a role in the prevention of antibiotic-associated AKI; however, definitive data from human studies are lacking. Few studies have investigated the benefits of natural products as preventative therapies for AKI in humans. Those that have been completed are primarily observational in nature and require confirmation in additional larger randomized controlled trials. There are several important considerations when evaluating the current state of the evidence and future directions for research. First, AKI is not exclusively caused by oxidative stress, and the pathophysiology of injury may be immune-mediated which would not respond to antioxidants. Second, the active constituent and its consistency in the natural product must be identified to choose a source appropriately. Third, the dose of active constituents in the natural product must be attainable in humans. Doses used in cell culture and animal studies may be outside the limit of possibility in humans. In such cases, novel formulations with concentrated active constituents may require development and further study. Finally, many natural products have not undergone extensive toxicologic evaluations to determine off-target effects nor evaluations for impurities. In summary, enthusiasm for using natural products to prevent AKI must be tempered with careful evaluation in preclinical models and controlled human studies.

Summary and conclusions

Data from preclinical models suggest that natural products may help reduce AKI. While these data have been corroborated in observational human clinical studies, additional larger randomized controlled trials are essential to determine the safety and efficacy of using natural products as reno-protective agents.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01DK131214. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: Luigi Brunetti reports financial support was provided by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Luigi Brunetti reports a relationship with Tabula Rasa HealthCare that includes board membership. Luigi Brunetti reports a relationship with Merck & Co Inc that includes funding grants. Luigi Brunetti reports a relationship with CSL Behring LLC that includes funding grants.

Footnotes

CRediT author statement

Luigi Brunetti: conceptualization, visualization, reviewing and editing, supervision. Thomas Hong: writing-original draft preparation, data extraction, reviewing and editing. Kelsey Briscese: writing-original draft preparation, data extraction. Marshall Yuan: data extraction, writing- reviewing and editing.

References

Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review, have been highlighted as:

** of outstanding interest

- 1.Mehta RL, Cerda J, Burdmann EA, et al. : International Society of Nephrology’s 0by25 initiative for acute kidney injury (zero preventable deaths by 2025): a human rights case for nephrology. Lancet 2015, 385:2616–2643. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60126-X. 20150313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Susantitaphong P, Cruz DN, Cerda J, et al. : World incidence of AKI: a meta-analysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2013, 8: 1482–1493. 10.2215/CJN.00710113. 20130606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hosohata K: Role of oxidative stress in drug-induced kidney injury. Int J Mol Sci 2016, 17, 20161101. 10.3390/ijms17111826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reis AM, Cassiani SH: Adverse drug events in an intensive care unit of a university hospital. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2011, 67:625–632. 10.1007/s00228-010-0987-y. 20110119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Che ML, Yan YC, Zhang Y, et al. : [Analysis of drug-induced acute renal failure in Shanghai]. Zhonghua Yixue Zazhi 2009, 89: 744–749. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choudhury D, Ahmed Z: Drug-associated renal dysfunction and injury. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol 2006, 2:80–91. 10.1038/ncpneph0076. 2006/08/26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ciarimboli G, Ludwig T, Lang D, et al. : Cisplatin nephrotoxicity is critically mediated via the human organic cation transporter 2. Am J Pathol 2005, 167:1477–1484. 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61234-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pagliarini DJ, Calvo SE, Chang B, et al. : A mitochondrial protein compendium elucidates complex I disease biology. Cell 2008, 134:112–123. 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ralto KM, Parikh SM: Mitochondria in acute kidney injury. Semin Nephrol 2016, 36:8–16. 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2016.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sandoval RM, Molitoris BA: Gentamicin traffics retrograde through the secretory pathway and is released in the cytosol via the endoplasmic reticulum. Am J Physiol Ren Physiol 2004, 286: F617–F624. 10.1152/ajprenal.00130.2003. 20031118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ott M, Gogvadze V, Orrenius S, et al. : Mitochondria, oxidative stress and cell death. Apoptosis 2007, 12:913–922. 10.1007/s10495-007-0756-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zager RA: Gentamicin effects on renal ischemia/reperfusion injury. Circ Res 1992, 70:20–28. 10.1161/01.res.70.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao L, Xu L, Tao X, et al. : Protective effect of the total flavonoids from Rosa Laevigata Michx fruit on renal ischemia-reperfusion injury through suppression of oxidative stress and inflammation. Molecules 2016, 21, 20160721. 10.3390/molecules21070952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krishnan N, Perazella MA: Drug-induced acute interstitial nephritis: pathology, pathogenesis, and treatment. Iran J Kidney Dis 2015, 9:3–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neilson EG: Pathogenesis and therapy of interstitial nephritis. Kidney Int 1989, 35:1257–1270. 10.1038/ki.1989.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang J, Liu Y: Dissection of key events in tubular epithelial to myofibroblast transition and its implications in renal interstitial fibrosis. Am J Pathol 2001, 159:1465–1475. 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62533-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fang CY, Lou DY, Zhou LQ, et al. : Natural products: potential treatments for cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2021, 42:1951–1969. 10.1038/s41401-021-00620-9. 20210309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ** This study provides a robust review of natural products and their role in the prevention of cisplatin induced nephrotoxicity.

- 18.Panche AN, Diwan AD, Chandra SR: Flavonoids: an overview. J Nutr Sci 2016, 5:e47. 10.1017/jns.2016.41. 20161229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hanasaki Y, Ogawa S, Fukui S: The correlation between active oxygens scavenging and antioxidative effects of flavonoids. Free Radic Biol Med 1994, 16:845–850. 10.1016/0891-5849(94)90202-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chung HY, Baek BS, Song SH, et al. : Xanthine dehydrogenase/xanthine oxidase and oxidative stress. Age 1997, 20:127–140. 10.1007/s11357-997-0012-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pietta PG: Flavonoids as antioxidants. J Nat Prod 2000, 63: 1035–1042. 10.1021/np9904509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen Y, Miao Y, Huang L, et al. : Antioxidant activities of saponins extracted from Radix Trichosanthis: an in vivo and in vitro evaluation. BMC Compl Alternative Med 2014, 14:86. 10.1186/1472-6882-14-86. 20140305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tapondjou LA, Nyaa LB, Tane P, et al. : Cytotoxic and antioxidant triterpene saponins from Butyrospermum parkii (Sapotaceae). Carbohydr Res 2011, 346:2699–2704. 10.1016/j.carres.2011.09.014. 20110924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Domitrovic R, Cvijanovic O, Pernjak-Pugel E, et al. : Berberine exerts nephroprotective effect against cisplatin-induced kidney damage through inhibition of oxidative/nitrosative stress, inflammation, autophagy and apoptosis. Food Chem Toxicol 2013, 62:397–406. 10.1016/j.fct.2013.09.003. 20130908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perazella MA: Pharmacology behind common drug nephrotoxicities. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2018, 13:1897–1908. 10.2215/CJN.00150118. 20180405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen LF, Kaye D: Current use for old antibacterial agents: polymyxins, rifamycins, and aminoglycosides. Infect Dis Clin 2009, 23:1053–1075. 10.1016/j.idc.2009.06.004. x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lopez-Novoa JM, Quiros Y, Vicente L, et al. : New insights into the mechanism of aminoglycoside nephrotoxicity: an integrative point of view. Kidney Int 2011, 79:33–45. 10.1038/ki.2010.337. 20100922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martinez-Salgado C, Eleno N, Tavares P, et al. : Involvement of reactive oxygen species on gentamicin-induced mesangial cell activation. Kidney Int 2002, 62:1682–1692. 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tajiri K, Miyakawa H, Marumo F, et al. : Increased renal susceptibility to gentamicin in the rat with obstructive jaundice. Role of lipid peroxidation. Dig Dis Sci 1995, 40:1060–1064. 10.1007/BF02064199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morales AI, Buitrago JM, Santiago JM, et al. : Protective effect of trans-resveratrol on gentamicin-induced nephrotoxicity. Antioxidants Redox Signal 2002, 4:893–898. 10.1089/152308602762197434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kandemir FM, Ozkaraca M, Yildirim BA, et al. : Rutin attenuates gentamicin-induced renal damage by reducing oxidative stress, inflammation, apoptosis, and autophagy in rats. Ren Fail 2015, 37:518–525. 10.3109/0886022X.2015.1006100. 20150123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kadkhodaee M, Khastar H, Faghihi M, et al. : Effects of co-supplementation of vitamins E and C on gentamicin-induced nephrotoxicity in rat. Exp Physiol 2005, 90:571–576. 10.1113/expphysiol.2004.029728. 20050315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sharma I, Liao Y, Zheng X, et al. : Modulation of gentamicin-induced acute kidney injury by myo-inositol oxygenase via the ROS/ALOX-12/12-HETE/GPR31 signaling pathway. JCI Insight 2022, 7, 20220322. 10.1172/jci.insight.155487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ** This study provides a novel mechanism of gentamicin-induced kidney injury and suggests the ALOX-12 pathway as a potential target for preventing this injury.

- 34.Dai C, Li H, Wang Y, et al. : Inhibition of oxidative stress and ALOX12 and NF-kappaB pathways contribute to the protective effect of baicalein on carbon tetrachloride-induced acute liver injury. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 20210618. 10.3390/antiox10060976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.St Laurent G 3rd, Toma I, Seilheimer B, et al. : RNAseq analysis of treatment-dependent signaling changes during inflammation in a mouse cutaneous wound healing model. BMC Genom 2021, 22:854. 10.1186/s12864-021-08083-2. 20211125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Du H, Li Z, Yang Y, et al. : New insights into the vancomycin-induced nephrotoxicity using in vitro metabolomics combined with physiologically based pharmacokinetic modeling. J Appl Toxicol 2020, 40:897–907. 10.1002/jat.3951. 20200220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ** This study provides insight into the importance of kidney tissue concentration versus plasma concentration and its role in toxicity.

- 37.Gupta A, Biyani M, Khaira A: Vancomycin nephrotoxicity: myths and facts. Neth J Med 2011, 69:379–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nolin TD: Vancomycin and the risk of AKI: now clearer than Mississippi Mud. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2016, 11:2101–2103. 10.2215/CJN.11011016. 20161128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kan WC, Chen YC, Wu VC, et al. : Vancomycin-associated acute kidney injury: a narrative review from pathophysiology to clinical application. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 20220212. 10.3390/ijms23042052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ocak S, Gorur S, Hakverdi S, et al. : Protective effects of caffeic acid phenethyl ester, vitamin C, vitamin E and N-acetylcysteine on vancomycin-induced nephrotoxicity in rats. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2007, 100:328–333. 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2007.00051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li J, Nation RL, Milne RW, et al. : Evaluation of colistin as an agent against multi-resistant Gram-negative bacteria. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2005, 25:11–25. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2004.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Falagas ME, Kasiakou SK: Colistin: the revival of polymyxins for the management of multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacterial infections. Clin Infect Dis 2005, 40:1333–1341. 10.1086/429323. 20050322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eljaaly K, Bidell MR, Gandhi RG, et al. : Colistin nephrotoxicity: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Open Forum Infect Dis 2021, 8:ofab026. 10.1093/ofid/ofab026. 20210121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gai Z, Samodelov SL, Kullak-Ublick GA, et al. : Molecular mechanisms of colistin-induced nephrotoxicity. Molecules 2019, 24, 20190212. 10.3390/molecules24030653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ordooei Javan A, Shokouhi S, Sahraei Z: A review on colistin nephrotoxicity. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2015, 71:801–810. 10.1007/s00228-015-1865-4. 20150527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yousef JM, Chen G, Hill PA, et al. : Ascorbic acid protects against the nephrotoxicity and apoptosis caused by colistin and affects its pharmacokinetics. J Antimicrob Chemother 2012, 67:452–459. 10.1093/jac/dkr483. 20111128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bader Z, Waheed A, Bakhtiar S, et al. : Alpha-tocopherol ameliorates nephrotoxicity associated with the use of colistin in rabbits. Pak J Pharm Sci 2018, 31:463–467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yousef JM, Chen G, Hill PA, et al. : Melatonin attenuates colistin-induced nephrotoxicity in rats. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2011, 55:4044–4049. 10.1128/AAC.00328-11. 20110627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee TW, Bae E, Kim JH, et al. : The aqueous extract of aged black garlic ameliorates colistin-induced acute kidney injury in rats. Ren Fail 2019, 41:24–33. 10.1080/0886022X.2018.1561375. 2019/02/05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mahmoud YI, Farag S: Kiwifruit ameliorates gentamicin induced histological and histochemical alterations in the kidney of albino mice. Biotech Histochem 2017, 92:357–362. 10.1080/10520295.2017.1318222. 20170609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shirwaikar A, Issac D, Malini S: Effect of Aerva lanata on cisplatin and gentamicin models of acute renal failure. J Ethnopharmacol 2004, 90:81–86. 10.1016/j.jep.2003.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moreira Galdino P, Nunes Alexandre L, Fernanda Pacheco L, et al. : Nephroprotective effect of Rudgea viburnoides (Cham.) Benth leaves on gentamicin-induced nephrotoxicity in rats. J Ethnopharmacol 2017, 201:100–107. 10.1016/j.jep.2017.02.035. 20170224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Aldahmash BA, El-Nagar DM, Ibrahim KE: Reno-protective effects of propolis on gentamicin-induced acute renal toxicity in swiss albino mice. Nefrologia 2016, 36:643–652. 10.1016/j.nefro.2016.06.004. 20160826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hsu DZ, Li YH, Chu PY, et al. : Sesame oil prevents acute kidney injury induced by the synergistic action of aminoglycoside and iodinated contrast in rats. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2011, 55:2532–2536. 10.1128/AAC.01597-10. 20110314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jose SP, A S, Im K, et al. : Nephro-protective effect of a novel formulation of unopened coconut inflorescence sap powder on gentamicin induced renal damage by modulating oxidative stress and inflammatory markers. Biomed Pharmacother 2017, 85:128–135. 10.1016/j.biopha.2016.11.117. 20161205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cekmen M, Otunctemur A, Ozbek E, et al. : Pomegranate extract attenuates gentamicin-induced nephrotoxicity in rats by reducing oxidative stress. Ren Fail 2013, 35:268–274. 10.3109/0886022X.2012.743859. 20121126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hussain T, Gupta RK, Sweety K, et al. : Nephroprotective activity of Solanum xanthocarpum fruit extract against gentamicin-induced nephrotoxicity and renal dysfunction in experimental rodents. Asian Pac J Trop Med 2012, 5:686–691. 10.1016/S1995-7645(12)60107-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Beshay ON, Ewees MG, Abdel-Bakky MS, et al. : Resveratrol reduces gentamicin-induced EMT in the kidney via inhibition of reactive oxygen species and involving TGF-beta/Smad pathway. Life Sci 2020, 258, 118178. 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.118178. 20200731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dumludag B, Derici MK, Sutcuoglu O, et al. : Role of silymarin (Silybum marianum) in the prevention of colistin-induced acute nephrotoxicity in rats. Drug Chem Toxicol 2022, 45: 568–575. 10.1080/01480545.2020.1733003. 20200316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Erseckin V, Mert H, Irak K, et al. : Nephroprotective effect of ferulic acid on gentamicin-induced nephrotoxicity in female rats. Drug Chem Toxicol 2022, 45:663–669. 10.1080/01480545.2020.1759620. 20200430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hassanein EHM, Ali FEM, Kozman MR, et al. : Umbelliferone attenuates gentamicin-induced renal toxicity by suppression of TLR-4/NF-kappaB-p65/NLRP-3 and JAK1/STAT-3 signaling pathways. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 2021, 28:11558–11571. 10.1007/s11356-020-11416-5. 20201030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Laorodphun P, Cherngwelling R, Panya A, et al. : Curcumin protects rats against gentamicin-induced nephrotoxicity by amelioration of oxidative stress, endoplasmic reticulum stress and apoptosis. Pharm Biol 2022, 60:491–500. 10.1080/13880209.2022.2037663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Qu S, Dai C, Hao Z, et al. : Chlorogenic acid prevents vancomycin-induced nephrotoxicity without compromising vancomycin antibacterial properties. Phytother Res 2020, 34: 3189–3199. 10.1002/ptr.6765. 20200710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ** This study supports a major role of oxidative stress in vancomycin-induced kidney injury and a role for chlorogenic acid in the amelioration of nephrotoxicity secondary to vancomycin.

- 64.Salama SA, Arab HH, Maghrabi IA: Troxerutin down-regulates KIM-1, modulates p38 MAPK signaling, and enhances renal regenerative capacity in a rat model of gentamycin-induced acute kidney injury. Food Funct 2018, 9:6632–6642. 10.1039/c8fo01086b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sarwar S, Hossain MJ, Irfan NM, et al. : Renoprotection of selected antioxidant-rich foods (water spinach and red grape) and probiotics in gentamicin-induced nephrotoxicity and oxidative stress in rats. Life 2022, 12, 20220103. 10.3390/life12010060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang J, Ishfaq M, Fan Q, et al. : 7-Hydroxycoumarin attenuates colistin-induced kidney injury in mice through the decreased level of histone deacetylase 1 and the activation of Nrf2 signaling pathway. Front Pharmacol 2020, 11:1146. 10.3389/fphar.2020.01146. 20200728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Worakajit N, Thipboonchoo N, Chaturongakul S, et al. : Nephroprotective potential of Panduratin A against colistin-induced renal injury via attenuating mitochondrial dysfunction and cell apoptosis. Biomed Pharmacother 2022, 148:112732. 10.1016/j.biopha.2022.112732. 20220224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Uzun-Goren D, Uz YH: Protective effect of curcumin against gentamicin-induced nephrotoxicity mediated by p38 MAPK, nuclear factor- kappa B, nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2. Iran J Kidney Dis 2022, 16:96–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ** This study supports the use of curcumin in preventing gentamicin-induced nephrotoxicity through the suppression of p38 MAPK and NFKβ and activation of Nrf2.

- 69.Sirijatuphat R, Limmahakhun S, Sirivatanauksorn V, et al. : Preliminary clinical study of the effect of ascorbic acid on colistin-associated nephrotoxicity. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015, 59:3224–3232. 10.1128/AAC.00280-15. 20150323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Badri S, Soltani R, Sayadi M, et al. : Effect of N-acetylcysteine against vancomycin-induced nephrotoxicity: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Arch Iran Med 2020, 23:397–402. 10.34172/aim.2020.33. 20200601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ** This study supports the use of N-acetylcysteine, a free radical scavenger, in the prevention of vancomycin-induced nephrotoxicity.

- 71.Soltani R, Khorvash F, Meidani M, et al. : Vitamin E in the prevention of vancomycin-induced nephrotoxicity. Res Pharm Sci 2020, 15:137–143. 10.4103/1735-5362.283813. 20200511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ** This study supports Vitamin E as an antioxidant for the prevention of acute kidney injury.

- 72.Hong TS, Briscese K, Yuan M, et al. : Renoprotective effects of melatonin against vancomycin-related acute kidney injury in hospitalized patients: a retrospective cohort study. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2021, 65:e0046221–e20210817. 10.1128/AAC.00462-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ** This study represents one of the few studies providing evidence on the association between melatonin supplementation and a reduction in acute kidney injury.

- 73.Tune BM: Mechanism of the mitochondrial respiratory toxicity of cephalosporin antibiotics. Adv Exp Med Biol 1989, 252: 313–318. 10.1007/978-1-4684-8953-8_31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tune BM, Fravert D, Hsu CY: Oxidative and mitochondrial toxic effects of cephalosporin antibiotics in the kidney. A comparative study of cephaloridine and cephaloglycin. Biochem Pharmacol 1989, 38:795–802. 10.1016/0006-2952(89)90233-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Muthukumar T, Jayakumar M, Fernando EM, et al. : Acute renal failure due to rifampicin: a study of 25 patients. Am J Kidney Dis 2002, 40:690–696. 10.1053/ajkd.2002.35675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kodner CM, Kudrimoti A: Diagnosis and management of acute interstitial nephritis. Am Fam Physician 2003, 67: 2527–2534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Oktem F, Arslan MK, Ozguner F, et al. : In vivo evidences suggesting the role of oxidative stress in pathogenesis of vancomycin-induced nephrotoxicity: protection by erdosteine. Toxicology 2005, 215:227–233. 10.1016/j.tox.2005.07.009. 20050819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Qu S, Dai C, Lang F, Hu L, Tang Q, Wang H, et al. : Rutin attenuates vancomycin-induced nephrotoxicity by ameliorating oxidative stress, apoptosis, and inflammation in rats. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2019, 63. 10.1128/AAC.01545-18.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Shi H, Zou J, Zhang T, Che H, Gao X, Wang C, et al. : Protective Effects of DHA-PC against Vancomycin-Induced Nephrotoxicity through the Inhibition of Oxidative Stress and Apoptosis in BALB/c Mice. J Agric Food Chem 2018, 66:475–484. 10.1021/acs.jafc.7b04565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]