Abstract

A putative cleavage site of the human foamy virus (HFV) envelope glycoprotein (Env) was altered. Transient env expression revealed that the R572T mutant Env was normally expressed and modified by asparagine-linked oligosaccharide chains. However, this single-amino-acid substitution was sufficient to abolish all detectable cleavage of the gp130 precursor polyprotein. Cell surface biotinylation demonstrated that the uncleaved mutant gp130 was transported to the plasma membrane. The uncleaved mutant protein was incapable of syncytium formation. Glycoprotein-driven virion budding, a unique aspect of HFV assembly, occurred despite the absence of Env cleavage. We then substituted the R572T mutant env into a replication-competent HFV molecular clone. Transfection of the mutant viral DNA into BHK-21 cells followed by viral titration with the FAB (foamy virus-activated β-galactosidase expression) assay revealed that proteolysis of the HFV Env was essential for viral infectivity. Wild-type HFV Env partially complemented the defective virus phenotype. Taken together, these experimental results established the location of the HFV Env proteolytic site; the effects of cleavage on Env transport, processing, and function; and the importance of Env proteolysis for virus maturation and infectivity.

Foamy viruses (FV) are grouped together as the spumavirus family of complex retroviruses and are ubiquitous in several mammalian species (7). The genomes of these complex retroviruses are comprised of the three typical retrovirus genes (i.e., gag, pol, and env) in addition to the accessory bel genes. The Env of FV is a type 1 membrane-spanning protein that possesses the general structural features observed in all retroviral glycoproteins (20). Two forms of the HFV envelope proteins have been reported (9, 10, 16). The predominant form of HFV Env is synthesized as a polyprotein precursor (gp130) that is proteolytically cleaved to yield two mature subunits, SU (gp80) and TM (gp47) (10). The second form, expressed at 30 to 50% of the level of gp130, is a 170-kDa Env-Bet fusion protein. This is generated by an alternative splicing mechanism and currently its biological role is unknown (9, 16). One feature unique to FV Env relative to all other retroviral glycoproteins is the presence of the dilysine motif, or KKXX, an endoplasmic reticulum (ER) retrieval signal at the TM C terminus (13). It was demonstrated that this protein sorting signal is responsible for ER localization of the HFV glycoprotein (12) and the partitioning of HFV budding to intracellular membranes (11). A putative proteolytic processing site within Env (20) was conserved among all six FV sequences available for analysis (Table 1). This consensus tetrabasic motif, R/K-X-R/K-R, was previously identified as a putative proteolytic cleavage site for retroviral envelope glycoproteins (4). Processing of the polyprotein at this basic amino acid cluster is performed by subtilisin-like cellular endoproteases in late Golgi compartments (15). The polyprotein becomes cleaved at the carboxy-terminal side of the final arginine of the tetrabasic cluster, resulting in the mature SU and TM subunits. Mutations that ablate the ER retrieval motif of the HFV Env protein (13) resulted in significantly enhanced proteolytic processing of the polyprotein (12). Since HFV particles contain cleaved Env, viral maturation presumably disrupts ER localization of Env and results in Env proteolysis upon exposure to the Golgi endoproteases (11). In the present study, the objectives were (i) to experimentally establish the site of proteolytic cleavage in FV Env and (ii) to investigate the importance of FV Env polyprotein cleavage for other aspects of Env processing and function, for Env-driven virion budding, and for HFV infectivity.

TABLE 1.

Amino acid sequences at the putative proteolytic cleavage sites of FV envelope glycoproteins

| Virusa | Amino acid sequenceb |

|---|---|

| ↓ | |

| SFVcpz | ...N N R K R R S T... |

| SFV-1 | ...N K R K R R S V... |

| SFV-3 | ...L K R R K R S T... |

| FeFV | ...G R R Q R R S V... |

| BSV | ...S K R T R R S I... |

| HFV | ...N N R K R R S V... |

| HFVR572T | ...N N R K R T S V... |

SFVcpz, simian FV of chimpanzee; SFV-1, simian FV of rhesus macaque; SFV-3, simian FV of African green monkey; FeFV, feline FV; BSV, bovine syncytial virus; HFV, human FV (also now called SFVH, for SFV isolated from human tissue).

The amino acids of the putative tetrabasic cleavage sequences are shown in boldface and underlined. The arrow indicates the putative cleavage site. R572T indicates an R-to-T substitution mutation at residue 572.

A single-amino-acid substitution in the putative tetrabasic cleavage site of HFV Env abolished polyprotein cleavage.

The C-terminal arginine (underlined) of the putative HFV cleavage sequence (RKRR), which was absolutely conserved among six FV sequences (20), was changed to threonine (i.e., the R572T mutation) by using an oligonucleotide-directed site-specific mutagenesis method as described previously (12) (Table 1). Our laboratory had earlier demonstrated that disabling mutations to the ER retrieval signal of HFV Env (e.g., KKK to SSS) resulted in increased efficiency of recombinant Env polyprotein cleavage due to increased transport through the Golgi stacks (12). For example, the SSS ER retrieval mutant polyprotein was 42% cleaved, as opposed to the wild-type KKK polyprotein, which was only 3% cleaved after a 90-min chase (12). Therefore, in the present study, the mutation to the putative cleavage site, R572T, was engineered in both an ER retrieval mutant env gene (i.e., SSS) and ER-localized wild-type env (i.e., KKK) in pSVL expression plasmids (Promega, Inc.) to better analyze the effect of R572T on Env processing. The pSVL promoter is the simian virus 40 late promoter.

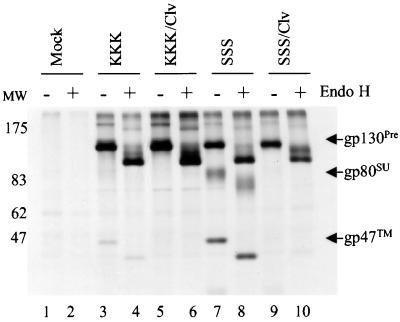

A pulse-chase analysis (1.5-h chase) of the effect of the R572T mutation on Env protein expression was performed (Fig. 1). COS-1 cells were transfected with the appropriate pSVL plasmids by using Lipofectamine (Life Technologies, Inc., Gaithersburg, Md.). Forty-eight hours posttransfection, cells were labeled with 35S protein labeling mix (100 μCi/ml; NEN) for 20 min, chased, harvested, and immunoprecipitated as described previously (12). Under these conditions, the KKK gp130 precursor was, as expected, only minimally cleaved into the mature subunits gp80 and gp47 (lane 3). This was because the KKK polyprotein was largely ER localized; hence its tetrabasic cluster was only minimally exposed to the cellular endoproteases in the distal Golgi apparatus. Nonetheless, a complete reduction in polyprotein gp130 cleavage was observed for KKK/clv, which possessed the R572T site mutation (compare lane 5 to lane 3).

FIG. 1.

Expression, proteolysis, and oligosaccharide modifications for the wild-type and R572T Env proteins. COS-1 cells were transfected with pSVL plasmids (Promega, Inc.) expressing KKK (ER retrieval competent) or SSS (ER retrieval mutant) FV glycoproteins with (KKK/clv or SSS/clv) or without the R572T cleavage site mutation. The cloning of HFV sequences into pSVL was described previously (12). Forty-eight hours posttransfection, the cells were labeled with 35S-protein labeling mix (NEN, Inc.) for 20 min and then chased for 1.5 h. Cells were lysed and immunoprecipitated with FV-positive chimpanzee plasma (kindly provided by P. Fultz). The samples were resuspended in 0.1 M sodium acetate (pH 5.5) and aliquoted. Samples were then incubated at 37°C for 16 h in the presence (+) or absence (−) of Endo H (50 mU/ml; Boehringer-Mannheim, Inc.) and resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-PAGE. The position of molecular mass markers (in kilodaltons) is shown on the left (MW).

A more vigorous test of the R572T mutant phenotype occurred with the SSS Env, which lacked a functional ER retrieval signal. Therefore, with SSS, the exposure of the tetrabasic motif to the trans-Golgi network was greater, and the Env polyprotein was more highly cleaved into gp80 and gp47 relative to KKK (compare lane 7 to lane 3). Nonetheless, a dramatic and complete loss of Env proteolysis was observed for the SSS/clv protein, which possessed the R572T mutation (compare lane 9 to lane 7). This experiment unequivocally demonstrated that the proteolytic processing of the R572T mutant was defective. The mutant phenotype was robust, because even the normally highly cleaved SSS glycoprotein remained uncleaved. After a 4-h chase, KKK/clv remained uncleaved, while very low levels of cleavage were detectable for SSS/clv (data not shown). Perhaps this low-level, late proteolysis represented inefficient cleavage of either the mutated primary cleavage sequence or secondary cleavage of an alternative sequence. Taken together, these results experimentally proved that the tetrabasic cluster RKRR is the primary HFV Env proteolytic site. Similar effects of a single-amino-acid substitution at the cleavage site were reported previously for other retroviral glycoproteins (3, 5, 8, 14).

Uncleaved R572T Env polyproteins are exposed to the Golgi environment.

Endoglycosidase H (Endo H) is an enzyme that specifically cleaves the high-mannose oligosaccharide side chains that are added to a peptide backbone in the ER. The conversion of Endo H-sensitive high-mannose N-linked glycans into complex-type sugars occurs in the medial or trans-Golgi compartments and confers Endo H resistance. In order to be certain that uncleaved R572T Env proteins were transported to Golgi compartments where the cellular endoproteases reside, we assessed the proteins' oligosaccharide processing by utilizing Endo H treatment. Following a 20-min labeling period with no chase, all four Env polyproteins (KKK, KKK/clv, SSS, and SSS/clv) were fully sensitive to Endo H (not shown). Following a 1.5-h chase, Endo H digestion of either the KKK or KKK/clv polyproteins produced a new major band with an apparent molecular mass of ∼100 kDa compared to the untreated 130-kDa polyprotein, indicating Endo H sensitivity (Fig. 1, compare lane 4 to lane 3 for KKK and compare lane 6 to lane 5 for KKK/clv). Only a small fraction of the KKK or KKK/clv polyproteins were partially resistant to Endo H (lanes 4 and 6, faint bands between ∼100 and 130 kDa). The Endo H sensitivity indicated that the KKK and KKK/clv polyproteins carried mainly high-mannose oligosaccharide side chains that hadn't been extensively modified by Golgi enzymes.

Interpretation of the Endo H results for the polyprotein, SU, and TM of SSS was difficult, since electrophoretic mobility was affected both by modification to complex carbohydrates and by proteolytic processing (lanes 7 and 8). Sequence analysis of the env open reading frame predicted the molecular masses of the unglycosylated precursor polyprotein, SU, and TM to be 104, 57, and 47 kDa, respectively. However, for the uncleaved SSS/clv polyprotein, Endo H treatment produced a second major band of ∼115 kDa, indicating that partial resistance to Endo H had developed during Golgi transport of the SSS/clv polyprotein (compare lane 10 to lane 9). The persistent Endo H-sensitive ∼100-kDa major band (lane 10) corresponded to the fraction of SSS/clv polyprotein that was not transported through the medial Golgi apparatus despite the SSS ER retrieval mutation. Similar results were obtained when the samples were chased for 4 h (data not shown). These results indicated that the ER retrieval-deficient SSS/clv polyprotein containing the R572T cleavage site mutation (lane 10) had clearly been exposed to the Golgi environment, since its oligosaccharides had acquired partial resistance to Endo H. Thus, the absence of cleavage was not due to a lack of transport of the mutant proteins to the Golgi apparatus, where cleavage normally occurs.

Uncleaved R572T Env polyproteins are transported to the plasma membrane.

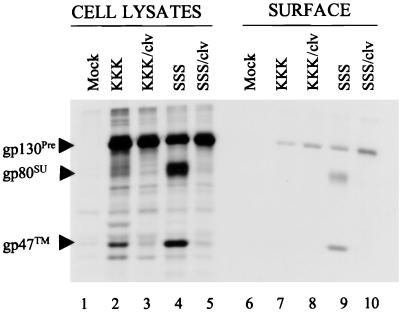

To analyze the effect of the R572T cleavage site mutation on the plasma membrane targeting of FV glycoproteins, the cell surface proteins of transfected COS-1 cells were biotinylated (Fig. 2). The total cellular immunoreactive proteins (lanes 1 to 5) or the subset of biotinylated (and hence surface) immunoreactive proteins (lanes 6 to 10) were visualized. As expected, in cell lysates, the KKK (lane 2) and SSS (lane 4) polyproteins were proteolytically processed—much more for SSS—whereas, the KKK/clv and SSS/clv polyproteins containing the R572T substitution remained uncleaved (lanes 3 and 5, respectively). For ER retrieval-deficient SSS, the precursor polyprotein, SU, and TM were detected on the cell surface (lane 9). For ER-localized KKK, only gp130 polyprotein was detected at the plasma membrane (lane 7). Prolonged exposure of the gel revealed very low levels of SU and TM on the surface of cells that expressed Env with the wild-type cleavage site and an intact ER retrieval signal (data not shown). For the cleavage site mutants KKK/clv and SSS/clv (lanes 8 and 10), the Env polyprotein alone was present at the plasma membrane. No cleavage products were observed even after prolonged exposure of the gel. The enhanced cell surface expression of SSS/clv relative to KKK/clv (compare lane 10 to 8) and the greater cleavage of gp130pre into SU and TM for SSS relative to KKK (compare lane 9 to lane 7) nicely demonstrated that mutation of the dilysine ER retrieval motif (in SSS) resulted in enhanced protein transport through the Golgi apparatus to the plasma membrane, as observed before (12). These results indicated that the R572T mutant Env polyproteins were competent for transport to the plasma membrane despite the absence of proteolytic processing.

FIG. 2.

Transport of the wild-type or R572T Env proteins to the plasma membrane. Transfected COS-1 cells were metabolically labeled and chased as described in the legend to Fig. 1. Cells were then washed with phosphate-buffered saline and incubated with biotin (EZ-link sulpho-NHS-SS-biotin; Pierce, Inc.) for 30 min at 4°C. The cells were then lysed and immunoprecipitated as before, and the samples were aliquoted. One aliquot was boiled for 5 min in the presence of 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and then reimmunoprecipitated with Streptavidin beads (Pierce, Inc.). The other aliquot was left untreated. Both aliquots were then boiled in sample reducing buffer and resolved by SDS-PAGE (12% polyacrylamide).

The uncleaved FV envelope glycoprotein was deficient in syncytium formation.

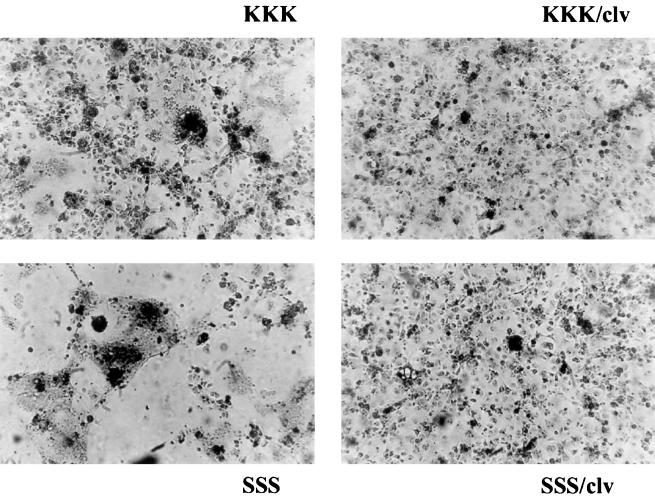

We next investigated the effect of HFV Env cleavage site mutation on syncytium formation (Fig. 3). Cells expressing the ER-localized KKK Env demonstrated a low level of cell fusion, whereas there was clearly an increase in production of multinucleated giant cells for SSS. The two R572T cleavage mutants (KKK/clv and SSS/clv) produced no cell fusion (Fig. 3). The results of qualitative scoring of syncytium formation by three blinded, independent observers were consistent: SSS (+++), KKK (++), KKK/clv (−), and SSS/clv (−). Wells containing mock-transfected cells did not contain any multinucleated cells (data not shown); i.e., they were identical to KKK/clv and SSS/clv, as shown. Taken together with the Endo H and surface biotinylation experiments, these results indicated that the uncleaved R572T Env polyproteins were normally expressed and transported through the Golgi apparatus and were further transported to the cell surface, but were nonfunctional in cell-to-cell fusion. The normal intracellular transport, oligosaccharide processing, and plasma membrane targeting of the HFV Env polyprotein in the absence of cleavage were similar to those reported for other retroviruses (17, 21).

FIG. 3.

Syncytium formation by the wild-type or R572T Env proteins. Forty-eight hours after transfection, COS-1 cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline and then fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde containing 0.1% Triton X-100 for 15 min at room temperature. Cells were then washed in phosphate-buffered saline before being stained with nuclear fast red for 30 min at room temperature. Stained cells were observed by light microscopy and photographed.

The R572T cleavage site mutation reduced HFV infectivity.

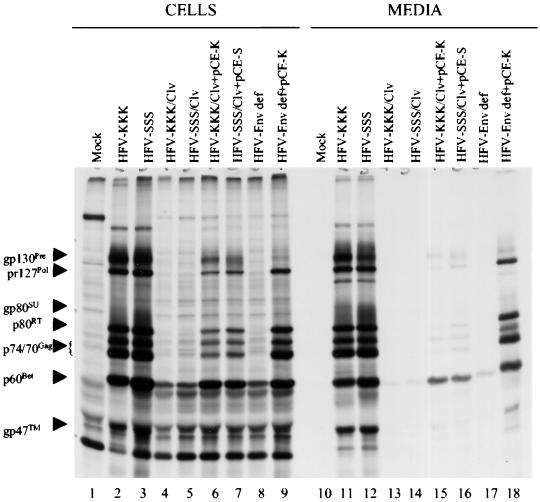

We next analyzed the importance of Env polyprotein cleavage for protein expression and infectivity in the context of the entire virus. The KKK/clv or SSS/clv env genes were substituted into an infectious HFV DNA clone, pHSRV1 (mod), which utilizes the HFV long terminal repeat promoter (kindly provided by Axel Rethwilm) (19). BHK-21 cells were transfected with the wild-type or R572T mutant proviral clones. Extensive vacuolization of the cells was observed at day 3 or 5 after transfection for HFV-KKK and HFV-SSS (data not shown). However, no cytopathic effect was observed for the R572T mutants (HFV-KKK/clv and HFV-SSS/clv). At day 5, the cells transfected with HFV-KKK or HFV-SSS DNA produced detectable HFV Env, Gag, and Bet proteins, as expected (Fig. 4, lanes 2 and 3). However, the predominant viral protein seen in cells for the R572T mutants HFV-KKK/clv and HFV-SSS/clv 22 was Bet (p60); only low levels of expression of the Gag polyprotein p74/70 were observed (Fig. 4, lanes 4 and 5). A similar pattern of gene expression was observed for the env-defective proviral DNA (described in the legend to Fig. 4 [lane 8]). However, significant increases in cellular expression of all HFV proteins by the R572T mutant clones were observed when cleaved Env proteins were provided in trans by cotransfection of pCE-K or pCE-S, which expressed KKK or SSS env, respectively, under the control of a cytomegalovirus promoter (compare lanes 6 and 7 to lanes 4 and 5). The transcomplementation results were even more pronounced when pCE-K was cotransfected with an env-defective provirus clone (compare lane 9 to lane 8).

FIG. 4.

Expression of HFV proteins by cells transfected with wild-type or mutant R572T proviral DNA clones. BHK-21 cells were transfected with proviral DNA and labeled at 96 h with 35S-protein labeling mix for 16 h. The culture media were filtered through 0.45-μm-pore-diameter filters. Cell lysate supernatants or media were immunoprecipitated with chimpanzee plasma, resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-PAGE, and visualized by autoradiography as before. HFV-Env def, the env-defective proviral clone, was created by site-directed mutagenesis with pALTER-1 (Promega, Inc.) as follows. Nucleotides A and G at positions 59 and 61 in env were changed to C and T, respectively, creating an early in-frame termination codon, as well as a unique Bsu36I site to screen for mutants. Also, a 971-bp internal deletion (nucleotides 164 to 1135) was created with EcoRV, followed by religation, which altered the reading frame.

Analysis of released viral proteins in the culture supernatants indicated that, in contrast to proviruses with wild-type cleavage sites where significant levels of virion proteins were released into the media (lanes 11 and 12), virion proteins were not released from cells transfected with the R572T mutant proviruses (lanes 13 and 14). Bet is a highly expressed viral protein that is secreted from the cells, but is not virion associated (2). These results suggested that the R572T mutation resulted in defective virus that failed to spread in culture after transfection, thus reducing expression of HFV proteins (lanes 4 and 5). However, detection of released virion proteins was partially restored when the cleaved Env protein was supplied in trans (lanes 15 and 16). Transcomplementation by cleaved Env was even more successful for the env-defective proviral clone (compare lanes 18 and 17). We speculate that Env complementation of R572T mutants was less efficient than for the env-defective provirus due to assembly of mixed Env oligomers composed of both cleaved and uncleaved Env monomers, which presumably would be less fit for virus entry.

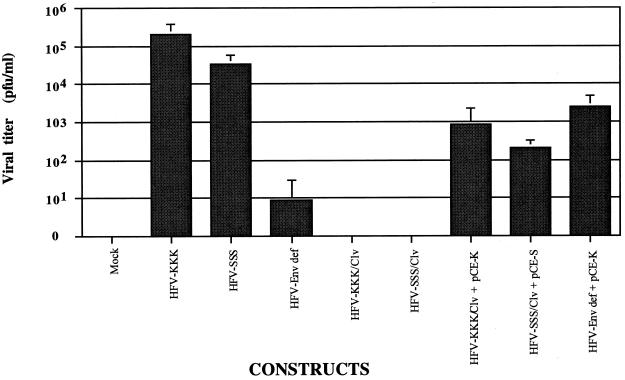

The titers of infectious HFV generated in parallel experiments were determined by using the FAB (Foamy virus-activated β-galactosidase expression) cell assay (22) (Fig. 5). Five days posttransfection, BHK cells were scraped from the culture dishes along with the supernatant. The samples were freeze-thawed three times to release the virus, and the FAB cell titration assay was then performed as previously described (22). The resulting virus titers clearly demonstrated that the cleavage-defective provirus was incapable of producing infectious virus. Transcomplementation of these defective proviruses with functional Env restored infectivity partially, but the titer remained ∼2 logs lower than that of the wild type.

FIG. 5.

FAB cell infectivity assay. Five days posttransfection with DNA constructs, the cells and media were harvested and freeze thawed three times to release virus. Virus titrations were then performed by infection of BHK/LTRlacZ indicator cells with 10-fold serial dilutions of the released virus preparations. Two days postinfection, the cells were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and fixed with 0.5% glutaraldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline. The blue foci were counted after the cells had been stained with chromogen. The means ± standard deviations for three independent experiments are shown.

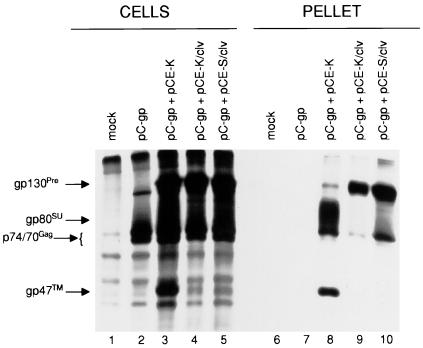

A possible explanation for the defective phenotype of the R572T mutant viruses was loss of glycoprotein-driven virion budding, an aspect of FV maturation which is unique relative to all other retroviruses (1, 6, 18; G. Wang, M. J. Mulligan, D. N. Baldwin, and M. L. Linial, Letter, J. Virol. 3:8917–, 1999. To test this hypothesis, an additional experiment which assessed budding independent of viral entry was performed (Fig. 6). For this experiment, we employed a CMV promoter-based overexpression system in 293T cells (6) and radioimmunoprecipitation-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). We coexpressed recombinant HFV Gag-Pol plasmid (provided by A. Rethwilm) with either wild-type or R572T Env. At 36 h posttransfection, the cells were metabolically labeled for 12 h, lysed, and immunoprecipitated as before. Culture media were centrifuged over a 20% sucrose cushion, and the pellets were then lysed and immunoprecipitated. Gag-Pol alone was incapable of releasing pelletable virus-like particles (Fig. 6, lane 7). However, when either wild-type Env or R572T mutant Env was coexpressed with Gag-Pol, both Gag and Env proteins were detected in pellets, indicating release of virus-like particles (Fig. 6, lanes 8, 9, and 10). More Gag was observed with the uncleaved SSS than the uncleaved KKK (compare lane 10 to lane 9), reinforcing the earlier observation that ablation of the ER retrieval signal does cause enhanced expression and budding at the plasma membrane (11). In parallel experiments, culture media were harvested for Western blotting at 48 h posttransfection and yielded similar results (data not shown). Taken together, these results proved that the uncleaved R572T Env mutants remained competent to stimulate particle budding.

FIG. 6.

Glycoprotein-driven budding of virus-like particles. Results of sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-PAGE of HFV proteins from 293T cells transfected with pC-gp expressing Gag plus Pol of HFV or with pC-gp plus Env expression plasmids. Following metabolic labeling at 36 h posttransfection, cells were lysed and immunoprecipitated with FV-specific chimpanzee plasma. Released virus particles were extracted from precleared cell culture supernatant by sedimentation through a 20% sucrose cushion (27,000 rpm for 3 h at 18°C in an SW41 rotor). The resulting pellet was lysed and immunoprecipitated as before.

Acknowledgments

We thank Om B. Bansal for valuable help. We are grateful to George Wang and Steffanie Sabbaj for assistance and Alesia L. Hatten for manuscript preparation.

This work was supported by Cystic Fibrosis Foundation grant R464 and USPHS awards CA09467, AI07493, AI01380, and AI27767.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baldwin D N, Linial M L. The roles of Pol and Env in the assembly pathway of human foamy virus. J Virol. 1998;72:3658–3665. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.3658-3665.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baunach G, Maurer B, Hahn H, Kranz M, Rethwilm A. Functional analysis of human foamy virus accessory reading frames. J Virol. 1993;67:5411–5418. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.9.5411-5418.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bosch V, Pawlita M. Mutational analysis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 env gene product proteolytic cleavage site. J Virol. 1990;64:2337–2344. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.5.2337-2344.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coffin J M. Genetic variation in AIDS viruses. Cell. 1986;46:1–4. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90851-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dubay J W, Dubay S R, Shin H-J, Hunter E. Analysis of the cleavage site of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 glycoprotein: requirement of precursor cleavage for glycoprotein incorporation. J Virol. 1995;69:4675–4682. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.8.4675-4682.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fischer N, Heinkelein M, Lindemann D, Enssle J, Baum C, Werder E, Zentgraf H, Müller J G, Rethwilm A. Foamy virus particle formation. J Virol. 1998;72:1610–1615. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.2.1610-1615.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flügel R M. The molecular biology of human spumavirus. In: Cullen B R, editor. Human retroviruses. Oxford, United Kingdom: IRL Press; 1993. pp. 193–214. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Freed E O, Myers D J, Risser R. Mutational analysis of the cleavage sequence of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein precursor gp160. J Virol. 1989;63:4670–4675. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.11.4670-4675.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giron M-L, de The H, Saïb A. An evolutionarily conserved splice generates a secreted Env-Bet fusion protein during human foamy virus infection. J Virol. 1998;72:4906–4910. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.6.4906-4910.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giron M-L, Rozain F, Debons-Guillemin M-C, Canivet M, Peries J, Emanoil-Ravier R. Human foamy virus polypeptides: identification of env and bel gene products. J Virol. 1993;67:3596–3600. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.6.3596-3600.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goepfert P A, Shaw K, Wang G, Bansal A, Edwards B H, Mulligan M J. An endoplasmic reticulum retrieval signal partitions human foamy virus maturation to intracytoplasmic membranes. J Virol. 1999;73:7210–7217. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.9.7210-7217.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goepfert P A, Shaw K L, Ritter G D, Jr, Mulligan M J. A sorting motif localizes the foamy virus glycoprotein to the endoplasmic reticulum. J Virol. 1997;71:778–784. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.1.778-784.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goepfert P A, Wang G, Mulligan M J. Identification of an ER retrieval signal in a retroviral glycoprotein. Cell. 1995;82:543–544. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90026-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guo H G, Veronese F, Tschachler E, Pal R, Kalyanaraman V S, Gallo R C, Reitz M S. Characterization of an HIV-1 point mutant blocked in envelope glycoprotein cleavage. Virology. 1990;174:217–224. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90070-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hallenberger S, Moulard M, Sordel M, Klenk H-D, Garten W. The role of eukaryotic subtilisin-like endoproteases for the activation of human immunodeficiency virus glycoproteins in natural host cells. J Virol. 1997;71:1036–1045. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.2.1036-1045.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lindemann D, Rethwilm A. Characterization of a human foamy virus 170-kilodalton Env-Bet fusion protein generated by alternative splicing. J Virol. 1998;72:4088–4094. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.4088-4094.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perez L G, Hunter E. Mutations within the proteolytic cleavage site of the Rous sarcoma virus glycoprotein that block processing to gp85 and gp37. J Virol. 1987;61:1609–1614. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.5.1609-1614.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pietschmann T, Heinkelein M, Heldmann M, Zentgraf H, Rethwilm A, Lindemann D. Foamy virus capsids require the cognate envelope protein for particle export. J Virol. 1999;73:2613–2621. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.4.2613-2621.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rethwilm A, Baunach G, Netzer K O, Maurer B, Borish B, ter Veulen V. Infectious DNA of the human spumaretrovirus. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:733–738. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.4.733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang G, Mulligan M J. Comparative sequence analysis and predictions for the envelope glycoproteins of foamy viruses. J Gen Virol. 1999;80:245–254. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-1-245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Willey R L, Klimkait T, Frucht D M, Bonifacino J S, Martin M A. Mutations within the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp160 envelope glycoprotein alter its intracellular transport and processing. Virology. 1991;184:319–329. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90848-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu S F, Linial M L. Analysis of the role of the bel and bet open reading frames of human foamy virus by using a new quantitative assay. J Virol. 1993;67:6618–6624. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.11.6618-6624.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]