The benefits of stroke rehabilitation services have been well documented for decades. 1 These benefits, such as improved poststroke upper extremity function, enhanced balance and gait speed, and reduced communication difficulties, can often be attributed to the care delivered by a skilled team of rehabilitation providers, such as physicians, nurses, physical and occupational therapists, and speech‐language pathologists. Consistent with other health care professionals, rehabilitation providers are trained to implement evidence‐based interventions, programs, and practices that have empirical support for improving stroke outcomes. Despite the importance and strong evidence‐base supporting rehabilitation services in the stroke field, not all groups of survivors of stroke, primarily marginalized populations, are provided with necessary and high‐quality rehabilitation care, threatening their ability to restore their functional independence. 2 This lack of equitable care—that is, care that is fair, just, and administered based on need rather than equally provided to all patients—is a major contributor to the rehabilitation outcome disparities (eg, community reintegration, functional outcomes) experienced by marginalized survivors of stroke. 3

A robust body of evidence has documented health disparities in stroke rehabilitation based on geographic location (eg, rural and urban settings), racial and ethnic differences, sex, and socioeconomic status (eg, lower income; insured and uninsured). 4 Geographic location substantially affects access to rehabilitation care as demonstrated by the 71% of all‐rural, US counties that do not have outpatient clinics that provide stroke rehabilitation services compared with 19% of nonrural counties. 5 Among patients receiving inpatient rehabilitation services post stroke, women—along with Black patients—were less likely to achieve optimal improvements according to the Functional Independence Measure, an 18‐item clinician reported scale that assesses functional capacity in six domains—mobility, transfers, self‐care, continence, cognition, and communication. 6 Survivors of stroke from lower‐income groups have also demonstrated poorer outcomes when attempting to reintegrate back into the community, which has devastating impacts on survivors' ability to return to key functional activities, such as securing and maintaining employment. 7

As the body of evidence underscoring health disparities has grown over the past several decades, the literature elucidating the reasons these health disparities exist is growing as well. In the context of stroke and neurological conditions more broadly, Towfighi et al. 8 identified 7 social determinants of health—or the conditions in the environment that affect health outcomes—that contribute to poststroke disparities: geographic place (eg, country, state, neighborhood), poverty and economic instability, schooling and education, food insecurity, housing insecurity, access to health care, and health literacy. For example, as Towfighi et al. note, structural racism that has been embedded in education systems may result in marginalized students having poorer educational experiences than their nonmarginalized peers, potentially altering cognitive development and increasing the risk of stroke in later adulthood. Given that structural determinants, such as schooling and education, certainly can influence stroke rehabilitation outcomes, Towfighi et al. 8 emphasize the importance of providers screening for these social determinants of health among their populations who have survived stroke to enhance the provision of equitable rehabilitation services.

Clearly, there is a pressing need to develop actionable solutions to reduce health disparities in stroke rehabilitation. To advance health equity in stroke rehabilitation care, it has been recommended that stroke researchers and rehabilitation care providers learn and apply principles from the field of implementation science. Broadly defined, implementation science is the field of study that systematically examines the factors and strategies that influence the implementation of evidence‐based practices. 9 Implementation scientists embark on projects to improve the uptake (ie, use; adoption) of evidence‐based practices, including screening tools, assessments, interventions, and clinical guidelines that providers can implement with all patient populations. The field of implementation science was established in response to the 17‐year research‐to‐practice gap, indicating that there are several complex barriers limiting the ability of providers to implement evidence‐based practices into real‐world care, resulting in poor patient‐ and population‐level outcomes. These complex barriers may include those at the patient level (eg, negative beliefs about the health care system), provider level (lack of knowledge about health disparities), organizational level (eg, a work culture that fails to recognize disparities), system level (eg, limited insurance coverage options), and societal level (eg, structural racism, discrimination against marginalized groups). 10 Synthesizing effective strategies to advance health equity at each of these complex levels is outside the scope of this Viewpoint article; however, as a first step toward tackling the barriers that limit the provision of equitable care in stroke rehabilitation, we focus our attention on the provider‐level strategies that can be leveraged to overcome health disparities. Our rationale for underscoring the provider level stems from the need to offer providers actionable strategies that can be immediately used in rehabilitation practice. Accordingly, the purpose of this paper is 2‐fold. First, we present the provider‐level factors (the barriers) that contribute to health disparities in stroke rehabilitation. Next, we describe promising provider‐level implementation strategies that can be deployed in stroke rehabilitation and facilitate rehabilitation providers' delivery of equitable care.

PROVIDER‐LEVEL BARRIERS THAT CONTRIBUTE TO HEALTH DISPARITIES IN STROKE REHABILITATION

Extensive work has examined the implementation behaviors of providers, establishing theoretical constructs that can predict behavioral change. For instance, the COM‐B framework presents 3 conditions that shape human behavior (“B”): capability, opportunity, and motivation. 11 Capability refers to the skills, knowledge, or competence someone has to successfully implement high‐quality care, including equitable rehabilitation services. Opportunity is the availability and autonomy to implement such care. Lastly, motivation is the commitment to delivering high‐quality care to all patient groups. With these 3 conditions of the framework in mind, we present several provider‐level barriers that have arguably contributed to health disparities in stroke rehabilitation.

Capability Barriers

Prior calls to action related to equitable health care emphasize the need for cultural competence and humility training and screening for social determinants of health. 8 , 12 However, providers' capability to engage in such training and to develop new screening behaviors is threatened by new occupation‐related risks (eg, COVID‐19) and soaring rates of burnout. 13 The capability of providers to establish trust and therapeutic relationship is essential to delivering equitable services but can also be negatively affected by implicit bias. 14 Implicit bias—which operates as unintentional or even unconscious—can lead providers to develop inaccurate perceptions of a patient's prognosis, goals, and progress, all of which can contribute to the disparities in equitable care by influencing patient–provider interactions, plans of care, and outcomes.

Opportunity Barriers

Time and system support (eg, leadership, policies, incentives) are significant barriers to the provision of any evidence‐based practice, especially equitable care practices. Providers need time to participate in activities that will shift the culture of their organization to be more equitable, reflect on these activities, and apply their reflections and skills in an iterative, continuous learning cycle. 15 Providers also may lack system support for advocating for equitable incentive structures, developing and reinforcing processes to address social determinants of health, diversifying the workforce, and deploying antiracist policies. 14

Motivation Barriers

A qualitative study exploring barriers to equitable care revealed rehabilitation providers generally exhibited positive attitudes in the context of care for marginalized populations. However, it was noted that providers may be constrained by the health care system where they have little control over their environments and subsequently whether care is entirely equitable or not, 16 having potentially detrimental influences on provider motivation.

PROVIDER‐LEVEL STRATEGIES TO REDUCE HEALTH DISPARITIES IN STROKE REHABILITATION

Identifying the barriers that affect the implementation of high‐quality care is an important starting point before launching any projects or efforts to improve care delivery. Once these barriers are identified, researchers and providers can work collaboratively to select and deploy implementation strategies, otherwise known as the methods or techniques to promote the use of evidence in clinical and community settings. For instance, one highly cited taxonomy of implementation strategies—the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change taxonomy 17 —was developed by Powell and colleagues and lists a collection of strategies hypothesized to address barriers to implementation. Considering the provider‐level barriers described herein, emerging work has tested which implementation strategies may overcome these barriers and improve the provision of equitable care. Althoug the following strategies have yet to be tested with providers specifically in the stroke rehabilitation context, they may be generalizable to rehabilitation providers.

Provider‐Level Strategies to Improve Capability

Education and training‐based interventions have been commonly deployed with the intention to improve providers' capability—that is, their skills and knowledge—for delivering equitable care. Despite their frequent use, the results of these trainings for improving providers' skills and knowledge have been mixed. Specific to health equity, cultural competence training has been found to have medium‐to‐large effects on providers' awareness of racial disparities, transcultural self‐efficacy, and cultural knowledge 18 ; however, there is limited evidence suggesting that education‐based training leads to actual reductions in health disparities or changes in provider behavior. This is consistent with prior work suggesting that education‐based interventions alone are likely insufficient for improving the quality of care provided to patients, 19 unless used in combination with other strategies. In particular, training that is augmented with consultation activities have been effective for improving provider skill, knowledge, and use of evidence‐based practices, 20 indicating that providers may benefit from education‐based interventions, such as those that draw awareness to implicit biases, followed by consultations with individuals experienced in implementing equitable care in stroke rehabilitation.

Provider‐Level Strategies to Improve Opportunity

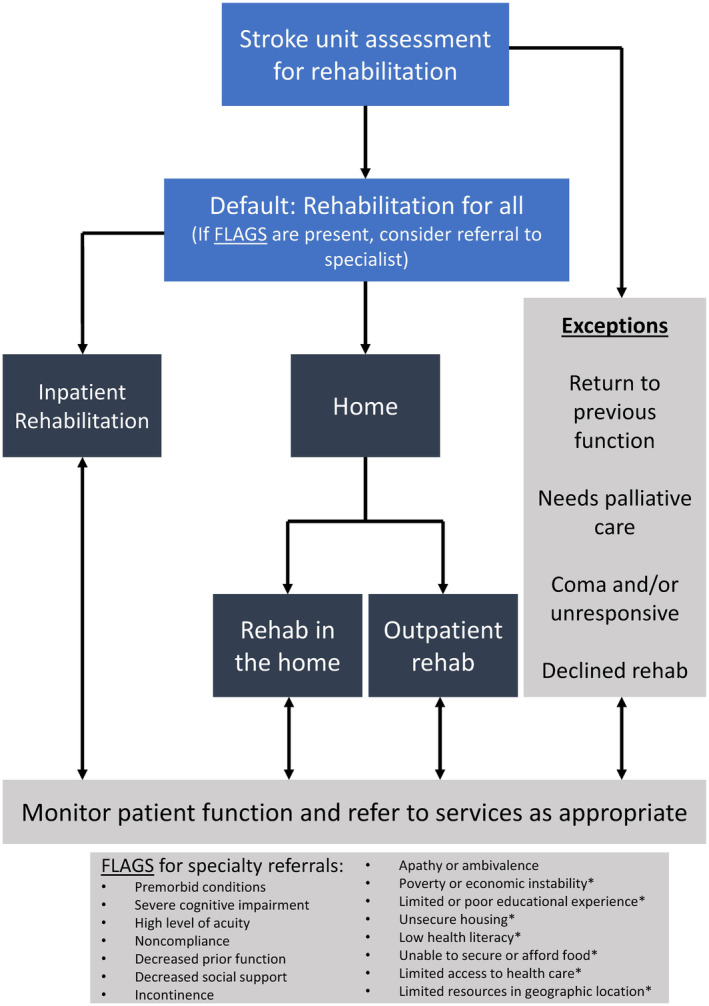

Certainly, rehabilitation providers will need sufficient time, or the opportunity, to develop and continuously refine their equitable practices. Although protected time may afford providers the opportunity to learn and deliver more equitable care, protected time may not be a feasible option for rehabilitation providers who face competing work demands (eg, productivity standards). Provider‐level strategies, such as training and educational interventions, can be time intensive; therefore, other strategies may be more efficient yet also effective for improving provider behavior. For instance, the use of computerized reminders to standardized care processes have successfully led to providers' delivering care that is just and fair to patient populations from racially and ethnically minoritized groups. 21 In the context of stroke rehabilitation, open access resources such as the Assessment for Rehabilitation Pathway and Decision‐Making Tool 22 was developed to assist providers in identifying patients appropriate for stroke rehabilitation services. Although pilot testing of this tool indicated that the time to complete the tool was viewed favorably by providers, its original version did not adequately take into consideration the social determinants of health affecting outcomes of marginalized survivors of stroke. Figure 1 presents our adapted version of the Assessment for Rehabilitation Pathway and Decision‐Making Tool, which includes the factors—based on existing literature—that may indicate a survivor of stroke is in need of specialty services to address social determinants of health. This tool may serve as an efficient option to support providers in their efforts to screen for such determinants, potentially reducing health disparities in stroke care.

Figure 1. Social determinants of health to consider when determining rehabilitation needs.

Light blue boxes indicate provider‐level process for determining appropriate rehabilitation referral; dark blue boxes indicate settings of rehabilitation referrals; gray boxes indicate factors for providers to consider when weighing rehabilitation referral options. *Denotes new flag to represent social determinants of health. The figure is adapted from open access materials made available through the Australian Stroke Coalition. 22 Copyright ©2012 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Provider‐Level Strategies to Improve Motivation

“Champions” are individuals who advocate for the use of particular practices within their organization and also provide support to peers who are less familiar or confident in their implementation behaviors. 17 In rehabilitation, champions may be especially effective for advancing health equity if they are invested in ensuring their work culture is committed to addressing the disparities experienced by marginalized groups. Providers who can serve as champions should be individuals who are respected by their peers and can be accessed for advice if other providers have difficulty delivering equitable care. Champions with strong communication and mentorship skills, in particular, have been effective for also increasing other providers' self‐efficacy towards implementing evidence‐based practices, which are skills champions can leverage to enhance the provision of equitable services as well. 23

Existing Implementation Science Resources and Tools

Over the past several years, the implementation science field has developed and disseminated resources and tools to help others identify the barriers limiting providers' implementation of high‐quality care—including equitable care—and the strategies to overcome such barriers. One such resource is the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR), which is a taxonomy of theory‐informed factors (ie, barriers) that influence the provision of evidence‐based practices. 24 Once barriers are identified, strategies can be selected and deployed to mitigate these barriers and arguably improve services. To assist providers in selecting strategies that are most salient to their implementation barriers, the CFIR and Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) developers collaborated to create the CFIR‐ERIC matching tool. The tool can be accessed through the CFIR's technical assistance website (https://cfirguide.org/choosing‐strategies/) along with several additional resources for providers interested in imbedding implementation science principles into their work. On the technical assistance website, we encourage rehabilitation providers to access the “implementation strategy selection tool” and select the specific “characteristics of the individual” (eg, knowledge and beliefs, self‐efficacy) that are perceived to limit their delivery of equitable services. Once these characteristics are selected, providers can then activate the “query” option, after which the tool will display recommended strategies (eg, conduct educational meetings; identify and prepare champions) to address selected barrier characteristics. More information about the CFIR‐Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change matching tool and its development and use can be found in the original publication by Waltz et al. 25

CONCLUSION

This Viewpoint article serves to (1) increase providers' awareness of several health disparities that exist among marginalized survivors of stroke and (2) introduce stroke rehabilitation providers to practical tools and resources that can advance the implementation of equitable services. The provision of care that is fair and just and tailored to patients' personal and cultural needs also has great potential to reduce the risk of preventable outcomes (eg, falls at home and subsequent hospital readmission) that are costly to both the patient and the health care system.

Equity in stroke rehabilitation cannot be achieved without actionable solutions to address the well‐documented disparities experienced by survivors of stroke. The strategies and recommendations presented in this article take into thoughtful consideration the competing demands of rehabilitation providers who want to mitigate stroke rehabilitation inequities but need practical strategies that effectively improve their delivery of equitable services. Though further work is needed to test the impact of these strategies on provider behavior and poststroke outcomes—and additional efforts are warranted to identify barriers and strategies to advance health equity in low‐ and middle‐income countries—the strategies described in this Viewpoint article may serve as helpful recommendations for providers committed to delivering equitable care with marginalized populations with stroke. Notably, we recognize that several complex and dynamic factors at the systems, organizational, and patient levels heavily influence care quality and need to be addressed alongside factors at the provider level as well.

Sources of Funding

Allison M. Gustavson was supported through the following: Veteran Affairs Health Services Research and Development, Center for Care Delivery and Outcomes Research (CCDOR), CIN 13‐406 and Veteran Affairs Rehabilitation Research and Development Rehabilitation & Engineering Center for Optimizing Veteran Engagement & Reintegration (RECOVER), A4836‐C; Lisa A. Juckett, Nneka L. Ifejika, and Mayowa Owolabi received partial funding to attend the 2023 International Stroke Conference as part of the HEADS‐UP: Health Equity and Actionable Disparities in Stroke: Understanding and Problem‐solving Pre‐Conference Institute. Mayowa Owolabwas supported through the following: National Institutes of Health NIH/NINDS SIREN (U54HG007479), SIBS Genomics (R01NS107900), and SIBS Gen Gen (R01NS107900‐02S1), ARISES (R01NS115944‐01), H3Africa CVD Supplement (3U24HG009780‐03S5), CaNVAS (1R01NS114045‐01), Sub‐Saharan Africa Conference on Stroke (SSACS) 1R13NS115395‐01A1, Training Africans to Lead and Execute Neurological Trials & Studies (TALENTS) D43TW012030, Growing Data‐science Research in Africa to Stimulate Progress (GRASP) UE5HL172183.

Disclosures

None.

The opinions expressed in this article are not necessarily those of the editors or of the American Heart Association.

This work was presented at the HEADS‐UP (Health Equity and Actionable Disparities in Stroke: Understanding and Problem‐Solving) Symposium, February 7, 2023.

This article was sent to Jose R. Romero, MD, Associate Editor, for review by expert referees, editorial decision, and final disposition.

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 6.

References

- 1. Evidence Based Review in Stroke Rehabilitation . Chaper 5: the efficacy of stroke rehabilitation. Accessed August 9, 2023. http://www.ebrsr.com/sites/default/files/ch5_v19.pdf.

- 2. Towfighi A, Boden‐Albala B, Cruz‐Flores S, El Husseini N, Odonkor CA, Ovbiagele B, Sacco RL, Skolarus LE, Thrift AG; American Heart Association Stroke Council , et al. Strategies to reduce racial and ethnic inequities in stroke preparedness, care, recovery, and risk factor control: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Stroke. 2023;54:e371–e388. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nkimbeng M, Fashaw‐Walters S. To advance health equity for dual‐eligible beneficiaries, we need culturally appropriate services. Health Affairs Forefront. 2022. doi: 10.1377/forefront.20220906.219675 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chavez AA, Simmonds KP, Venkatachalam AM, Ifejika NL. Health care disparities in stroke rehabilitation. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am:1–11. 2023. doi: 10.1016/j.pmr.2023.06.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wozny J, Parker D, Sonawane K, Russell M, Savitz S, Zamin S, Zhu Y. Surveying stroke rehabilitation in Texas: capturing geographic disparities in outpatient clinic availability…American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine (ACRM) Annual Conference (Virtual), September 24–29, 2021. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2021;102:e29–e30. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2021.07.544 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Somani S, Nanavati H, Zhou X, Lin C. African Americans and women have lower functional gains during acute inpatient rehabilitation after hemorrhagic stroke. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2022;101:1099–1103. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0000000000001964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brey JK, Wolf TJ. Socioeconomic disparities in work performance following mild stroke. Disabil Rehabil. 2015;37:106–112. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2014.909535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Towfighi A, Berger RP, Corley AMS, Glymour MM, Manly JJ, Skolarus LE. Recommendations on social determinants of health in neurologic disease. Neurology. 2023;101:S17–S26. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000207562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Eccles MP, Mittman BS. Welcome to implementation science. Implement Sci. 2006;1:1. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-1-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Woodward EN, Matthieu MM, Uchendu US, Rogal S, Kirchner JE. The health equity implementation framework: proposal and preliminary study of hepatitis C virus treatment. Implement Sci. 2019;14:26. doi: 10.1186/s13012-019-0861-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci. 2011;6:42. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-6-42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bowen CN, Havercamp SM, Karpiak Bowen S, Nye G. A call to action: preparing a disability‐competent health care workforce. Disabil Health J. 2020;13:100941. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2020.100941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Linzer M, Jin JO, Shah P, Stillman M, Brown R, Poplau S, Nankivil N, Cappelucci K, Sinsky CA. Trends in clinician burnout with associated mitigating and aggravating factors during the COVID‐19 pandemic. JAMA Health Forum. 2022;3:e224163. doi: 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2022.4163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lentz TA, Coronado RA, Master H. Delivering value through equitable care for low back pain: a renewed call to action. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2022;52:414–418. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2022.10815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rocco TS, Smith MC, Mizzi RC, Merriweather LR, Hawley JD. The Handbook of Adult and Continuing Education. Routledge; 2023:1–524. doi: 10.4324/9781003447849 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. McCoy AR, Polsunas P, Borecky K, Brane L, Day J, Ferber G, Harris K, Hickman C, Olsen J, Sherrier M, et al. Reaching for equitable care: high levels of disability‐related knowledge and cultural competence only get us so far. Disabil Health J. 2022;15:101317. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2022.101317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, Damschroder LJ, Smith JL, Matthieu MM, Proctor EK, Kirchner JE. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implement Sci. 2015;10:21. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0209-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chae D, Kim J, Kim S, Lee J, Park S. Effectiveness of cultural competence educational interventions on health professionals and patient outcomes: a systematic review. Jpn J Nurs Sci. 2020;17:e12326. doi: 10.1111/jjns.12326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Forsetlund L, O'Brien MA, Forsén L, Mwai L, Reinar LM, Okwen MP, Horsley T, Rose CJ. Continuing education meetings and workshops: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;2021:CD003030. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003030.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lyon AR, Liu FF, Connors EH, King KM, Coifman JI, Cook H, McRee E, Ludwig K, Law A, Dorsey S, et al. How low can you go? Examining the effects of brief online training and post‐training consultation dose on implementation mechanisms and outcomes for measurement‐based care. Implement Sci Commun. 2022;3:79. doi: 10.1186/s43058-022-00325-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Williams JS, Walker RJ, Egede LE. Achieving equity in an evolving healthcare system: opportunities and challenges. Am J Med Sci. 2016;351:33–43. doi: 10.1016/j.amjms.2015.10.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Australian Stroke Coalition . Assessment for rehabilitation: pathway and decision‐making tool. Accessed January 4, 2024. https://australianstrokecoalition.org.au/projects/assessment‐for‐rehabilitation/.

- 23. Morena AL, Gaias LM, Larkin C. Understanding the role of clinical champions and their impact on clinician behavior change: the need for causal pathway mechanisms. Front Health Serv. 2022;2:896885. doi: 10.3389/frhs.2022.896885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Damschroder LJ, Reardon CM, Widerquist MAO, Lowery J. The updated consolidated framework for implementation research based on user feedback. Implement Sci. 2022;17:75. doi: 10.1186/s13012-022-01245-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Waltz TJ, Powell BJ, Fernández ME, Abadie B, Damschroder LJ. Choosing implementation strategies to address contextual barriers: diversity in recommendations and future directions. Implement Sci. 2019;14:42. doi: 10.1186/s13012-019-0892-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]