Abstract

Background

Minimally invasive mitral valve repair has a favorable risk–benefit profile in patients with significant de novo mitral regurgitation. Its role in patients with prior mitral valve repair is uncertain. We aimed to appraise the outcome of patients undergoing transcatheter edge‐to‐edge repair (TEER) with prior transcatheter or surgical mitral valve repair (SMVR).

Methods and Results

We queried the Italian multicenter registry on TEER with MitraClip, distinguishing naïve patients from those with prior TEER or (SMVR). Inhospital and long‐term clinical/echocardiographic outcomes were appraised. The primary outcome was the occurrence of death or rehospitalization for heart failure. A total of 2238 patients were included, with 2169 (96.9%) who were naïve to any mitral intervention, 29 (1.3%) with prior TEER, and 40 (1.8%) with prior SMVR. Several significant differences were found in baseline clinical and imaging features. Respectively, device success was obtained in 2120 (97.7%), 28 (96.6%), and 38 (95.0%, P=0.261) patients; procedural success in 2080 (95.9%), 25 (86.2%), and 38 (95.0%; P=0.047); and inhospital death in 61 (2.8%), 1 (3.5%), and no (P=0.558) patients. Clinical follow‐up after a mean of 14 months showed similar rates of death, cardiac death, rehospitalization, rehospitalization for heart failure, and their composite (all P>0.05). Propensity score–adjusted analysis confirmed unadjusted analysis, with lower procedural success for the prior TEER group (odds ratio, 0.28 [95% CI, 0.09–0.81]; P=0.019) but similar odds ratios and hazard ratios for all other outcomes in the naïve, TEER, and SMVR groups (all P>0.05).

Conclusions

In carefully selected patients, TEER can be performed using the MitraClip device even after prior TEER or SMVR.

Keywords: MitraClip, mitral regurgitation, mitral valve repair, transcatheter edge‐to‐edge repair, transcatheter mitral valve repair

Subject Categories: Valvular Heart Disease, Heart Failure, Treatment, Aortic Valve Replacement/Transcather Aortic Valve Implantation, Behavioral/Psychosocial Treatment

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- GIOTTO

GIse Registry of Transcatheter Treatment of Mitral Valve Regurgitation

- GIOTTO‐FAILS

GIse Registry of Transcatheter Treatment of Mitral Valve Regurgitation‐FAILureS

- SMVR

surgical mitral valve repair

- TEER

transcatheter edge‐to‐edge repair

Clinical Perspective.

What Is New?

Transcatheter mitral edge‐to‐edge repair is becoming an established alternative to surgical mitral valve repair in patients at increased surgical risk with suitable anatomic features.

While initially reserved for individuals without prior mitral repair, transcatheter mitral edge‐to‐edge repair can also be performed in carefully selected patients with prior surgical or transcatheter mitral valve repair.

Despite a lower procedural success in patients with prior transcatheter mitral valve repair in comparison to naïve patients, transcatheter mitral edge‐to‐edge repair is associated with favorable results for other short‐term outcomes and also for long‐term events in patients with prior transcatheter or surgical mitral valve repair.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Transcatheter edge‐to‐edge repair can be safely and effectively performed using the MitraClip device even in carefully selected patients with a clinical history of prior transcatheter or surgical mitral valve repair.

Mitral regurgitation is a common cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, and poses several challenges, especially when significant comorbidities coexist. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 While surgical mitral valve repair (SMVR) has been considered the gold‐standard treatment of mitral regurgitation for several decades, its invasiveness is still a limitation, especially in patients at increased surgical risk. 5 , 6 Transcatheter edge‐to‐edge repair (TEER) was introduced several years ago as a minimally invasive alternative to SMVR in carefully selected cases, and, despite some inconsistencies between pivotal trials, TEER has become a mainstay in the management of mitral regurgitation. 7 , 8 , 9 , 10

While these premises hold robustly in patients with de novo mitral regurgitation, individuals with prior SMVR or TEER represent a uniquely challenging setting. 11 , 12 First, they are typically at high surgical risk because of advanced age, coexistent cardiovascular conditions, or substantial comorbidities. 13 Second, leaflet anatomy may be significantly distorted and thus limit treatment options. Third, the presence of an annular ring or a previous clip may lead to increased transmitral valve gradients. 14 Fourth, left ventricular dysfunction commonly accompanies failing mitral valve repairs, and thus may limit patient resilience as well as long‐term prognosis after discharge. 15

While several reports on TEER after failed SMVR or TEER are available, their scope and focus may limit generalization and warrant further research. Thus, we aimed to utilize the multicenter Italian Society of Interventional Cardiology GIOTTO (GIse Registry of Transcatheter Treatment of Mitral Valve Regurgitation) to compare patients naïve to any mitral valve intervention with patients who had prior TEER or SMVR. 16

METHODS

Details of the GIOTTO on TEER with MitraClip (Abbott Vascular) have been reported elsewhere in detail, as well as in the corresponding ClinicalTrials.gov entry (NCT03521921). 16 , 17 Briefly, the study protocol was approved by each participating site's institutional review board and the patients provided written informed consent and were included in case TEER was attempted, without any exclusion criteria except for lack of consent to participate. Accordingly, all analyses followed an intention‐to‐treat principle.

Indications for TEER were as per routine care and, thus, significant mitral regurgitation and valve anatomy suitable for TEER with MitraClip as per transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography. Current clinical practice guidelines, recommendations, and consensus statements were duly followed in the diagnostic, planning, procedural, and follow‐up phases. Procedures were performed under systematic transesophageal echocardiographic guidance and either deep sedation or general anesthesia at the operator's discretion. Given the protracted enrollment in the study over several years, different MitraClip generations were used, from NT to NTr and XTr.

Clinical follow‐up, echocardiographic follow‐up, and ancillary medical management were performed according to standard care and ongoing guidelines, with direct visits every 1 to 3 months up to 12 months, and then every 12 months. Similarly, transthoracic echocardiography was routinely repeated to evaluate cardiac dimensions, function, and valve features. Mitral Valve Academic Research Consortium recommendations were used for the adjudication of events, with short‐term outcomes including device success, procedural success, death, bailout mitral valve surgery, partial device detachment, device embolization, bleeding, vascular complication, stroke, transient ischemic attack, cardiac tamponade, myocardial infarction, and total hospital stay (Data S1). Notably, left ventricular ejection fraction, mitral valve gradient, mitral regurgitation grade, and systolic pulmonary artery pressure were systematically assessed before discharge. 18 Long‐term clinical outcomes included death, mitral valve surgery, heart transplantation, endocarditis, rehospitalization, and heart failure (HF) grade. Follow‐up imaging details included left ventricular ejection fraction, mitral valve gradient, mitral regurgitation grade, tricuspid regurgitation grade, and systolic pulmonary artery pressure.

Descriptive analysis was based on reporting mean±SD and count (percentage) for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. Unadjusted inferential analysis was based on ANOVA, with post hoc Student t test, Fisher exact test, logistic regression, Cox proportional hazard analysis, Kaplan‐Meier curves, and log‐rank test, as appropriate. In particular, binary logistic regression was used to appraise the association between inhospital outcomes (ie, device success, procedural success, and inhospital death) considered as dependent variables, and several independent variables, iteratively. Cox proportional hazard analysis was used to appraise the association between outcomes occurring over time (ie, death, cardiac death, rehospitalization, rehospitalization for HF, HF, death or rehospitalization, and cardiac death or rehospitalization for HF) and several independent variables, iteratively. Notably, adjusted analysis was performed using binary logistic regression and Cox proportional hazard analysis, as appropriate, leveraging nonparsimonious propensity scores using an inverse probability of treatment weighting approach. 19 Notably, all outcomes were analyzed only individually, with the exceptions of death, cardiac death, rehospitalization, and rehospitalization for HF, which were analyzed individually, as well as 2 composites: death or rehospitalization and cardiac death or rehospitalization for HF. Statistical significance was set at the 0.05 2‐tailed level, without multiplicity adjustment. Computations were performed with Stata 13 (StataCorp LLC). The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

RESULTS

A total of 2238 patients were included, with 2169 (96.9%) naïve to any mitral valve intervention, 29 (1.3%) with prior TEER with MitraClip, and 40 (1.8%) with prior SMVR (Table 1). Notably, no device different from the MitraClip was previously used in any patient. Focusing on baseline features, there were significant differences in terms of cause, with degenerative mitral regurgitation more common in patients with prior SMVR, while functional dilated mitral regurgitation was more common in the TEER group (P<0.001). Similarly, New York Heart Association functional class IV was higher in patients with prior TEER and, to a lesser extent, patients naïve to intervention (P=0.001). Patients naïve to mitral valve intervention more frequently had a history of myocardial infarction (P=0.002) and coronary artery disease (P=0.032), whereas those with prior TEER more commonly had prior hospitalization for HF (P=0.004). Finally, renal function was less impaired in patients with prior SMVR (P<0.001). Echocardiographic features were significantly different as well, including left ventricular end‐diastolic diameter, end‐systolic diameter, end‐diastolic volume, end‐systolic volume, left ventricular ejection fraction, mitral regurgitation severity, mitral valve gradient, presence of flail leaflet, and tricuspid regurgitation grade (all P<0.05; Table S1).

Table 1.

Baseline Features Comparing Patients Naïve to Mitral Valve Intervention With Patients Who Had Prior TEER or SMVR

| Feature | Naïve | Prior TEER | Prior SMVR | Overall P value | Subgroup P value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, n | 2169 | 29 | 40 | … | … |

| Age, y | 75.9±9.1 | 73.2±9.4 | 70.0±12.2 | <0.001 | 0.234 |

| Women | 795 (36.7) | 12 (41.4) | 14 (35.0) | 0.835 | 0.623 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 25.3±4.3 | 25.8±5.4 | 25.0±4.6 | 0.733 | 0.509 |

| Mitral disease cause | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| Degenerative | 677 (31.2) | 6 (20.7) | 27 (67.5) | ||

| Functional dilated | 639 (29.5) | 14 (48.3) | 8 (20.0) | ||

| Functional ischemic | 616 (28.4) | 8 (27.6) | 3 (7.5) | ||

| Mixed | 237 (10.9) | 1 (3.5) | 2 (5.0) | ||

| NYHA class IV | 187 (8.7) | 4 (13.8) | 0 | 0.001 | <0.001 |

| Logistic EuroSCORE | 14.7±12.7 | 18.5±17.9 | 11.7±9.9 | 0.320 | 0.194 |

| EuroSCORE II | 6.6±6.3 | 7.0±4.6 | 7.3±5.6 | 0.703 | 0.769 |

| STS score | 5.1±5.4 | 5.5±5.2 | 2.4±2.1 | 0.068 | 0.018 |

| Prior pacemaker implantation | 0.136 | 0.025 | |||

| No | 1318 (60.8) | 12 (41.4) | 29 (72.5) | ||

| Monocameral | 200 (9.2) | 2 (6.9) | 4 (10.0) | ||

| Bicameral | 334 (15.4) | 7 (24.1) | 4 (10.0) | ||

| Biventricular | 317 (14.6) | 8 (27.6) | 3 (7.5) | ||

| Prior ICD implantation | 667 (30.8) | 13 (44.8) | 7 (17.5) | 0.050 | 0.017 |

| Diabetes | 0.350 | 0.106 | |||

| No | 1601 (73.8) | 19 (65.5) | 35 (87.5) | ||

| Diet therapy | 56 (2.6) | 1 (3.5) | 1 (2.5) | ||

| Noninsulin drug therapy | 287 (13.2) | 6 (20.7) | 2 (5.0) | ||

| Insulin therapy | 225 (10.4) | 3 (10.3) | 2 (5.0) | ||

| Dyslipidemia | 727 (33.5) | 10 (34.5) | 9 (22.5) | 0.347 | 0.290 |

| Hypertension | 1575 (72.6) | 22 (75.9) | 25 (62.5) | 0.328 | 0.300 |

| Smoking history | 313 (14.4) | 6 (20.7) | 6 (15.0) | 0.545 | 0.542 |

| Carotid artery disease | 0.640 | 1 | |||

| No | 1987 (91.6) | 29 (100) | 38 (95.0) | ||

| <50% Stenosis | 135 (6.2) | 0 | 1 (2.5) | ||

| 50%–79% Stenosis | 41 (1.9) | 0 | 1 (2.5) | ||

| >79% Stenosis | 6 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | ||

| Peripheral artery disease | 164 (7.6) | 1 (3.5) | 4 (10.0) | 0.615 | 0.389 |

| Aortic valve disease | 0.451 | 0.112 | |||

| None | 1542 (71.1) | 22 (75.9) | 24 (60.0) | ||

| Mild stenosis | 50 (2.3) | 1 (3.5) | 1 (2.5) | ||

| Moderate stenosis | 35 (1.6) | 1 (3.5) | 0 | ||

| Aortic regurgitation | 510 (23.5) | 5 (17.2) | 15 (37.5) | ||

| Mixed aortic valve disease | 32 (1.5) | 0 | 0 | ||

| Prior myocardial infarction | 717 (33.1) | 6 (20.7) | 4 (10.0) | 0.002 | 0.302 |

| Prior hospitalization for heart failure | 1220 (56.3) | 20 (69.0) | 13 (32.5) | 0.004 | 0.004 |

| Syncope | 90 (4.2) | 0 | 1 (2.5) | 0.780 | 1 |

| Coronary artery disease | 892 (41.1) | 9 (31.0) | 9 (22.5) | 0.032 | 0.579 |

| Prior coronary revascularization | 226 (32.2) | 3 (37.5) | 2 (28.6) | 0.911 | 1 |

| Prior cardiac surgery | 463 (21.4) | 9 (31.0) | 40 (100) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Mitral annuloplasty | 0 | 0 | 8 (20.0) | … | … |

| Coronary artery bypass grafting | 305 (14.1) | 7 (24.1) | 4 (10.0) | 0.233 | 0.182 |

| Heart transplantation | 6 (0.3) | 0 | 1 (2.5) | 0.197 | 1 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 12.3±1.8 | 12.1±1.3 | 13.1±1.6 | 0.070 | 0.029 |

| Hematocrit, % | 38±5 | 38±4 | 39±4 | 0.374 | 0.543 |

| Platelet count | 208±73 | 215±75 | 197±63 | 0.694 | 0.397 |

| Estimated GFR, mL/min per 1.73 m2 | 48.3±24.7 | 54.2±19.5 | 62.3±27.8 | <0.001 | 0.184 |

| Formal contraindications to surgical repair | |||||

| Porcelain aorta | 9 (0.4) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Neoplasia | 65 (3.0) | 0 | 1 (2.5) | 1 | 1 |

| Hostile chest | 56 (2.6) | 1 (3.5) | 3 (7.5) | 0.095 | 0.634 |

| Frailty | 634 (29.2) | 14 (48.3) | 11 (27.5) | 0.089 | 0.127 |

| Neurologic disability | 39 (1.8) | 0 | 1 (2.5) | 0.717 | 1 |

| Collagenopathy | 10 (0.5) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Other | 365 (16.8) | 7 (24.1) | 14 (35.0) | 0.009 | 0.430 |

| Cirrhosis | 5 (0.2) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Dialysis | 43 (2.0) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| COPD | 327 (15.1) | 6 (20.7) | 7 (17.5) | 0.555 | 0.764 |

Values are expressed as number (percentage) or mean±SD unless otherwise indicated.

COPD indicates chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator; NYHA, New York Heart Association; and STS, Society of Thoracic Surgery.

Comparing patients with prior transcatheter edge‐to‐edge repair (TEER) vs those with prior surgical mitral valve repair (SMVR).

Procedural details and results were largely similar in the groups, despite a higher number of MitraClip devices being implanted in naïve patients (P<0.001), including NT devices (P<0.001), higher severity of residual mitral regurgitation (P=0.035), and lower postprocedural systolic blood pressure (P=0.047) in patients with prior TEER, and a higher prevalence of postprocedural physiologic pulmonary vein flow in naïve patients (P=0.002) (Table 2). Notably, rates of device success appeared similar in the 3 groups, while procedural success was lower in those with prior TEER (P=0.047).

Table 2.

Procedural Results Comparing Patients Naïve to Mitral Valve Intervention With Those Who Had Prior TEER or SMVR

| Feature | Naïve | Prior TEER | Prior SMVR | Overall P value | Subgroup P value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | 2169 | 29 | 40 | … | … |

| Systolic BP at baseline, mm Hg | 117±19 | 112±19 | 111±20 | 0.148 | 0.898 |

| Systolic BP at end of procedure, mm Hg | 117±18 | 110±13 | 120±20 | 0.047 | 0.015 |

| Fluoroscopy time, min | 1.5±3.7 | 2.2±5.1 | 2.0±7.8 | 0.510 | 0.942 |

| Device time, min | 2.8±2.1 | 2.4±1.4 | 2.3±1.0 | 0.149 | 0.818 |

| Operating room time, min | 6.2±3.2 | 5.7±2.5 | 6.1±1.8 | 0.632 | 0.434 |

| Intubation time, min | 1.6±11.7 | 1.5±5.8 | 1.5±5.0 | 0.997 | 0.956 |

| Failed MitraClip implantation | 13 (0.6) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Total MitraClip number | <0.001 | 0.798 | |||

| 1 | 857 (39.5) | 21 (72.4) | 26 (65.0) | ||

| 2 | 1103 (50.9) | 7 (24.1) | 13 (32.5) | ||

| 3 | 184 (8.5) | 1 (3.5) | 1 (2.5) | ||

| 4 | 14 (0.7) | 0 | 0 | ||

| 5 | 1 (0.1) | 0 | 0 | ||

| MitraClip NT | <0.001 | 1 | |||

| 1 | 423 (34.6) | 18 (78.3) | 11 (78.6) | ||

| 2 | 658 (53.8) | 4 (17.4) | 2 (14.3) | ||

| 3 | 129 (10.5) | 1 (4.4) | 1 (7.1) | ||

| 4 | 10 (0.8) | 0 | 0 | ||

| MitraClip NTr | 0.694 | 0.429 | |||

| 1 | 249 (67.1) | 2 (66.7) | 4 (100) | ||

| 2 | 110 (29.7) | 1 (33.3) | 0 | ||

| 3 | 7 (1.9) | 0 | 0 | ||

| 4 | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | ||

| MitraClip XTr | 0.413 | 0.598 | |||

| 1 | 499 (66.6) | 3 (75.0) | 11 (50.0) | ||

| 2 | 228 (30.4) | 1 (25.0) | 11 (50.0) | ||

| 3 | 19 (2.5) | 0 | 0 | ||

| 4 | 1 (0.1) | 0 | 0 | ||

| Pulmonary vein flow at end of procedure | 0.002 | 0.013 | |||

| Physiologic | 942 (43.4) | 5 (17.2) | 16 (40.0) | ||

| Blunted | 143 (6.6) | 1 (3.5) | 0 | ||

| Diastolic | 85 (3.9) | 4 (13.8) | 1 (2.5) | ||

| Inverted | 111 (5.1) | 5 (17.2) | 1 (2.5) | ||

| Reduced systolic function at inspection at end of procedure | 102 (4.7) | 1 (3.5) | 1 (2.5) | 1 | 1 |

| Mitral regurgitation at end of procedure | 0.035 | 0.068 | |||

| None | 1374 (63.4) | 14 (48.3) | 28 (70.0) | ||

| Mild | 692 (31.9) | 9 (31.0) | 11 (27.5) | ||

| Moderate | 68 (3.1) | 4 (13.8) | 1 (2.5) | ||

| Severe | 35 (1.6) | 2 (6.9) | 0 | ||

| Smoke‐like effect | 140 (6.5) | 2 (6.9) | 2 (5.0) | 0.925 | 1 |

| ECG changes | 251 (11.6) | 7 (24.1) | 4 (10.0) | 0.132 | 0.182 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 190 (8.8) | 4 (13.8) | 4 (10.0) | 0.486 | 0.712 |

| Ventricular tachycardia/fibrillation | 1 (0.1) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Device success | 2120 (97.7) | 28 (96.6) | 38 (95.0) | 0.261 | 1 |

| Procedural success | 2080 (95.9) | 25 (86.2) | 38 (95.0) | 0.047 | 0.230 |

| Procedural death | 5 (0.2) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

Values are expressed as number (percentage) or mean±SD unless otherwise indicated.

BP indicates blood pressure.

Comparing patients with prior transcatheter edge‐to‐edge repair (TEER) vs those with prior surgical mitral valve repair (SMVR).

Inhospital results were largely similar, including rates of death, stroke, myocardial infarction, bleeding, and vascular complication (all P>0.05; Table 3). Although left ventricular ejection fraction and mitral valve gradient appeared different, such discrepancies largely depended on baseline differences.

Table 3.

Inhospital Clinical and Imaging Outcomes Comparing Patients Naïve to Mitral Valve Intervention With Patients Who Had Prior TEER or SMVR

| Feature | Naïve | Prior TEER | Prior SMVR | Overall P value | Subgroup P value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | 2169 | 29 | 40 | … | … |

| Inhospital death | 61 (2.8) | 1 (3.5) | 0 | 0.558 | 0.420 |

| Stroke | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Transient ischemic attack | 0 | 0 | 1 (2.5) | 0.031 | 1 |

| Cardiac tamponade | 5 (0.2) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Myocardial infarction | 1 (0.1) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Bailout mitral valve surgery | 6 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Partial device detachment | 14 (0.7) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Device embolization | 9 (0.4) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Any bleeding | 19 (0.9) | 1 (3.5) | 0 | 0.348 | 0.420 |

| Minor bleeding | 11 (0.5) | 1 (3.5) | 0 | 0.161 | 0.420 |

| Major bleeding | 5 (0.2) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Disabling bleeding | 3 (0.1) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Red blood cell transfusion | 14 (0.7) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Any vascular complication | 15 (0.7) | 1 (3.5) | 0 | 0.215 | 0.420 |

| Minor vascular complication | 9 (0.4) | 1 (3.5) | 0 | 0.134 | 0.420 |

| Major vascular complication | 6 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Vessel perforation | 5 (0.2) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Femoral pseudoaneurysm | 2 (0.1) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Total hospital stay, d | 7.6±7.9 | 7.2±6.4 | 9.7±19.9 | 0.251 | 0.525 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction at discharge, % | 42.5±14.8 | 33.2±12.6 | 49.3±13.7 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Mitral gradient at discharge, mm Hg | 3.4±1.6 | 4.0±1.7 | 4.8±3.5 | <0.001 | 0.278 |

| Mitral gradient at least 5 mm Hg at discharge | 179 (8.3) | 4 (13.8) | 5 (12.5) | 0.281 | 1 |

| Change in mitral gradient from baseline to discharge, mm Hg | 1.0±1.4 | 2.0±1.6 | 2.1±4.9 | 0.075 | 0.583 |

| Mitral regurgitation at discharge | 0.245 | 0.472 | |||

| 1+ | 1215 (57.6) | 13 (46.4) | 23 (57.5) | ||

| 2+ | 735 (34.9) | 10 (35.7) | 13 (32.5) | ||

| 3+ | 121 (5.7) | 5 (17.9) | 3 (7.5) | ||

| 4+ | 37 (1.8) | 0 | 1 (2.5) | ||

| Systolic pulmonary artery pressure, mm Hg at discharge | 41±11 | 46±12 | 40±15 | 0.049 | 0.076 |

Values are expressed as number (percentage) or mean±SD unless otherwise indicated.

Comparing patients with prior transcatheter edge‐to‐edge repair (TEER) vs those with prior surgical mitral valve repair (SMVR).

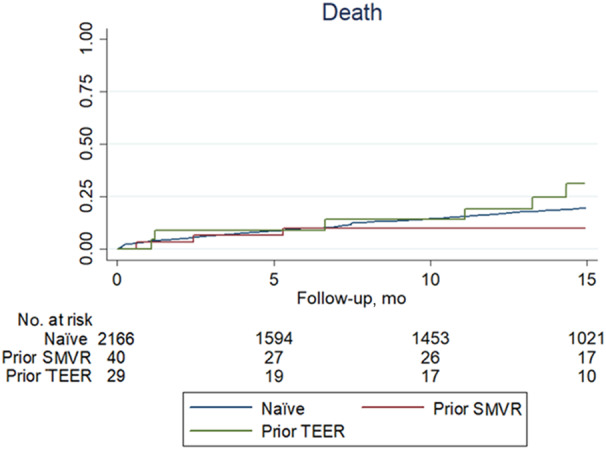

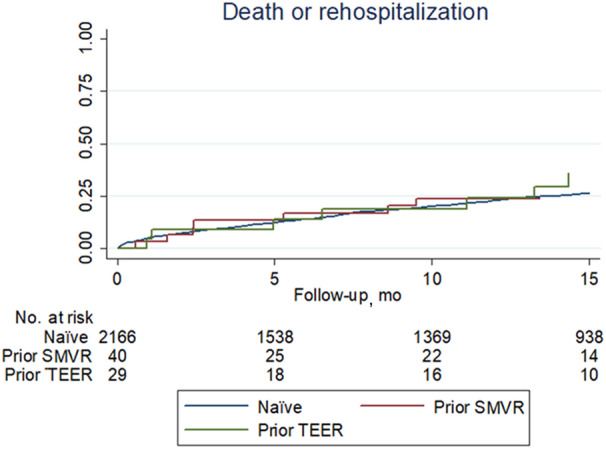

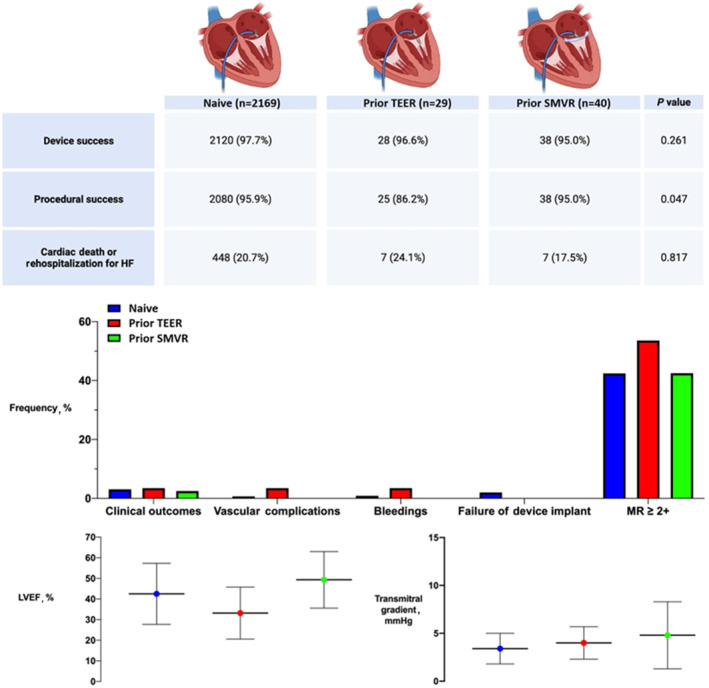

Long‐term management details are provided in Table S2 and long‐term outcomes in Table 4. Of note, after a mean follow‐up of 18 months, there were no significant differences in the rates of death, cardiac death, mitral valve surgery, rehospitalization, HF, or their key composites (all P>0.05; Figures 1, 2, 3). Echocardiography follow‐up confirmed that results accrued during the index hospitalization were well maintained during the subsequent follow‐up, with very low rates of severe mitral regurgitation, especially in nonnaïve patients.

Table 4.

Long‐Term Outcomes Comparing Patients Naïve to Mitral Valve Intervention With Patients Who Had Prior TEER or SMVR

| Feature | Naïve | Prior TEER | Prior SMVR | Overall P value | Subgroup P value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | 2169 | 29 | 40 | … | … |

| Follow‐up, mo | 18.7±16.4 | 13.5±12.4 | 15.5±13.6 | 0.110 | 0.520 |

| Death | 531 (24.5) | 8 (27.6) | 5 (12.5) | 0.195 | 0.131 |

| Cardiac death | 283 (13.1) | 5 (17.2) | 3 (7.5) | 0.483 | 0.266 |

| Mitral valve surgery | 24 (1.1) | 0 | 1 (2.5) | 0.545 | 1 |

| Heart transplantation | 9 (0.4) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Endocarditis | 5 (0.2) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Rehospitalization | 278 (12.8) | 5 (17.2) | 5 (12.5) | 0.744 | 0.732 |

| Rehospitalization for HF | 224 (10.3) | 4 (13.8) | 4 (10.0) | 0.734 | 0.712 |

| HF | 260 (12.0) | 5 (17.2) | 4 (10.0) | 0.581 | 0.477 |

| Death or rehospitalization | 670 (30.9) | 10 (34.5) | 9 (22.5) | 0.482 | 0.290 |

| Cardiac death or rehospitalization for HF | 448 (20.7) | 7 (24.1) | 7 (17.5) | 0.817 | 0.554 |

| NYHA class | 0.654 | 0.659 | |||

| I | 272 (17.5) | 2 (11.8) | 3 (13.0) | ||

| II | 932 (59.8) | 10 (58.8) | 16 (69.6) | ||

| III | 330 (21.2) | 5 (29.4) | 3 (13.0) | ||

| IV | 25 (1.6) | 0 | 1 (4.4) | ||

| Left ventricular ejection fraction, % | 40.9±14.3 | 30.3±7.2 | 47.8±10.1 | 0.001 | <0.001 |

| Mitral gradient, mm Hg | 3.9±1.8 | 4.7±2.3 | 5.5±3.4 | <0.001 | 0.516 |

| Change in mitral gradient from baseline to follow‐up, mm Hg | 1.5±1.6 | 1.5±1.3 | 2.2±4.8 | 0.551 | 0.789 |

| Change in mitral gradient from discharge to follow‐up, mm Hg | 0.3±1.6 | 0.7±1.9 | 0.5±1.3 | 0.358 | 0.621 |

| Mitral regurgitation | 0.513 | 0.220 | |||

| 1+ | 533 (41.3) | 5 (31.3) | 12 (54.6) | ||

| 2+ | 520 (40.3) | 9 (56.3) | 7 (31.8) | ||

| 3+ | 172 (13.3) | 2 (12.5) | 1 (4.6) | ||

| 4+ | 67 (5.2) | 0 | 2 (9.1) | ||

| Tricuspid regurgitation | 0.603 | 1 | |||

| 1+ | 31 (2.6) | 1 (6.3) | 1 (5.9) | ||

| 2+ | 549 (46.2) | 7 (43.8) | 8 (47.1) | ||

| 3+ | 462 (38.9) | 6 (37.5) | 5 (29.4) | ||

| 4+ | 147 (12.4) | 2 (12.5) | 3 (17.7) | ||

| Systolic pulmonary artery pressure, mm Hg | 40.9±11.6 | 44.7±14.2 | 37.4±12.2 | 0.214 | 0.131 |

HF indicates heart failure; and NYHA, New York Heart Association.

Values are expressed as number (percentage) or mean±SD unless otherwise indicated.

Comparing patients with prior transcatheter edge‐to‐edge repair (TEER) vs those with prior surgical mitral valve repair (SMVR).

Figure 1. Failure curves for death comparing patients naïve to mitral valve intervention with those who underwent prior transcatheter edge‐to‐edge repair (TEER) or prior surgical mitral valve repair (SVMR) (naïve vs TEER groups, P=0.282; TEER vs SMVR groups, P=0.089; and naïve vs SVMR groups, P=0.257).

Figure 2. Failure curves for the composite of death or rehospitalization comparing patients naïve to mitral valve intervention with those who underwent prior transcatheter edge‐to‐edge repair (TEER) or prior surgical mitral valve repair (SMVR) (naïve versus TEER groups, P=0.303; TEER vs SVMR groups, P=0.249; and naïve and SMVR groups, P=0.720).

Figure 3. Summary of the GIOTTO‐FAILS (GIse Registry of Transcatheter Treatment of Mitral Valve Regurgitation‐FAILureS) study.

Clinical outcomes represent the composite of inhospital death, stroke, transient ischemic attack, cardiac tamponade, myocardial infarction, or bailout mitral valve surgery. HF indicates heart failure; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MR, mitral regurgitation; SMVR, surgical mitral valve repair; and TEER, transcatheter edge‐to‐edge repair.

Exploratory adjusted analysis, despite being limited by the small sample size of the nonnaïve groups, confirmed that the outcome of patients with prior TEER and those with prior SMVR was similar to that of naïve individuals for all key outcomes, including death, cardiac death, rehospitalization, rehospitalization for HF, HF, and their most relevant composite (all P>0.05; Table 5; Table S3).

Table 5.

Unadjusted and Adjusted Analyses

| Outcomes and comparisons | Unadjusted effect estimates* | Adjusted effect estimates* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TEER vs naïve | TEER vs SMVR | SMVR vs naïve | TEER vs naïve | TEER vs SMVR | SMVR vs naïve | |

| Device success | OR=0.65 (0.09–4.85), P=0.672 | OR=1.47 (0.13–17.07), P=0.756 | OR=0.44 (0.10–1.87), P=0.266 | OR=0.76 (0.10–5.80), P=0.788 | OR=1.18 (0.99–1.40), P=0.067 | OR=0.54 (0.12–2.48), P=0.429 |

| Procedural success | OR=0.27 (0.09–0.79), P=0.016 | OR=0.33 (0.06–1.93), P=0.218 | OR=0.81 (0.19–3.42), P=0.778 | OR=0.28 (0.09–0.81), P=0.019 | OR=0.76 (0.10–5.80), P=0.788 | OR=0.84 (0.19–3.69), P=0.815 |

| Inhospital death | OR=1.23 (0.17–9.22), P=0.837 | … | … | OR=1.20 (0.16–8.94), P=0.862 | … | … |

| Death | HR=1.47 (0.73–2.95), P=0.282 | HR=2.84 (0.85–9.42), P=0.089 | HR=0.60 (0.25–1.45), P=0.257 | HR=1.29 (0.64–2.61), P=0.477 | HR=2.57 (0.76–8.70), P=0.129 | HR=0.84 (0.35–2.05), P=0.708 |

| Cardiac death | HR=1.64 (0.68–3.98), P=0.273 | HR=3.55 (0.69–18.31), P=0.130 | HR=0.66 (0.21–2.06), P=0.475 | HR=1.43 (0.59–3.51), P=0.427 | HR=2.84 (0.52–15.57), P=0.229 | HR=0.90 (0.35–3.43), P=0.881 |

| Rehospitalization | HR=1.66 (0.69–4.03), P=0.259 | HR=1.44 (0.42–4.99), P=0.562 | HR=1.17 (0.49–2.84), P=0.723 | HR=1.17 (0.48–2.88), P=0.723 | HR=1.15 (0.32–4.18), P=0.832 | HR=1.44 (0.59–3.51), P=0.416 |

| Rehospitalization for HF | HR=1.61 (0.60–4.33), P=0.346 | HR=1.44 (0.36–5.76), P=0.606 | HR=1.12 (0.42–3.02), P=0.819 | HR=1.10 (0.40–2.99), P=0.854 | HR=0.99 (0.23–4.37), P=0.994 | HR=1.36 (0.51–3.68), P=0.539 |

| HF | HR=1.74 (0.72–4.22), P=0.219 | HR=1.77 (0.48–6.61), P=0.393 | HR=0.97 (0.36–2.61), P=0.953 | HR=1.23 (0.50–3.01), P=0.652 | HR=1.32 (0.33–5.27), P=0.690 | HR=1.21 (0.45–3.25), P=0.709 |

| Death or rehospitalization | HR=1.39 (0.74–2.59), P=0.303 | HR=1.73 (0.68–4.38), P=0.249 | HR=0.89 (0.46–1.71), P=0.720 | HR=1.12 (0.59–2.10), P=0.732 | HR=1.50 (0.58–3.90), P=0.401 | HR=1.09 (0.56–2.11), P=0.792 |

| Cardiac death or rehospitalization for HF | HR=1.39 (0.66–2.94), P=0.384 | HR=1.61 (0.54–4.79), P=0.394 | HR=0.99 (0.47–2.09), P=0.976 | HR=1.08 (0.51–2.30), P=0.838 | HR=1.31 (0.42–4.05), P=0.644 | HR=1.28 (0.60–2.70), P=0.524 |

HF indicates heart failure; SMVR, surgical mitral valve repair; and TEER, transcatheter edge‐to‐edge repair.

Reported as odds ratios (ORs) or hazard ratios (HRs), as appropriate, with accompanying 95% CIs.

Finally, even opting for sensitivity purposes for a more penalizing 2‐tailed 0.005 cutoff to adjust for multiple testing, the main findings as reported in Table 5 remained consistent. The only shift in significance was limited to the borderline difference in procedural success at unadjusted analysis as reported in Table 2, which was no longer significant according to this more demanding threshold.

DISCUSSION

The management of patients with prior TEER or SMVR represents a substantial challenge. While awaiting the completion of prospective randomized trials on this niche area of cardiovascular practice, our observational evidence describes current practice and may be helpful in guiding decision‐making. Notably, we found that <4% of patients undergoing TEER in the current era report a history of TEER or SMVR. Significant differences among these 2 groups and naïve patients are apparent in terms of presenting features, including age, mitral regurgitation cause, history of myocardial infarction, and coronary artery disease. These differences are accompanied by significant variation in echocardiography features, with patients with prior TEER typically exhibiting worse remodeling patterns and more depressed systolic function. Nevertheless, clinical results in the 3 groups appear similar, at early as well as long‐term follow‐up, and even taking into account baseline differences. These results indicate that TEER can be safely offered in patients with prior TEER or prior SMVR, with favorable expectations for functional echocardiography and clinical improvement.

The evidence in favor of TEER continues to accrue, and these scientific and scholarly successes are mirrored by an ongoing growth in the use and confidence of this minimally invasive approach to treat mitral regurgitation. 20 While it is evident that intervention timing and patient selection have an impact on acute and long‐term outcomes as much as technical skills, 9 , 21 the confidence in TEER translates into its extension to patients who previously were considered suboptimal candidates. In such a setting, patients with prior TEER or SMVR constitute a small but inherently challenging niche. Clinical, anatomical, and technical issues are more relevant in these patients, and failures or suboptimal results are all possible. Indeed, procedural success was lower in patients with prior TEER, despite similar rates of acute device success. Irrespectively, clinical outcomes and echocardiographic findings at follow‐up were reassuring, suggesting that repeat TEER or TEER after failed SMVR remain safe and may provide meaningful clinical benefits even at longer follow‐up. It is also worth mentioning that most patients, regardless of the index intervention, received only one MitraClip, and an NT type, and yet there was a significant increase in transmitral gradients (actually more pronounced in patients with prior surgery). Indeed, the risk of significant gradient after implantation of a third MitraClip might be the main reason for limiting to only one MitraClip during the redo procedure. Yet, as a result of ongoing technological refinements, such as the introduction of the G4 system, it is plausible to expect further expansion of indications and improved results in the current and future eras. 22

Despite the validity of our detailed analysis, several unanswered questions remain. They include how to best select patients, how to gauge short‐ and long‐term results, how to follow individuals, when and why considering subjects for a redo TEER (which might in some cases come as a third TEER), how to combine TEER with other transcatheter mitral valve techniques (eg, transcatheter annuloplasty), and how to combine the benefits of transcatheter repair with maximization of medical therapy in the era of novel drugs such as sodium‐glucose transport protein 2 inhibitors and glucagon‐like peptide 1 receptor agonists.

Furthermore, several key limitations of the present work should be noted. Clearly, the observational design is a distinct weakness and the same applies to the small sample size, especially for the subset of patients with prior TEER. In addition, the enrollment of patients over several years is another limitation and the ensuing inclusion of patients treated with different device generations. Furthermore, this registry was designed as a single‐device study, and thus no patient received other available TEER technologies (eg, Pascal [Edwards Lifesciences]), nor transcatheter approaches other than TEER for transcatheter repair, such as Cardioband (Edwards Lifesciences) or AccuCinch (Ancora Heart), to name just a few. Future studies are also warranted to appraise the consistency of the present results in other settings and on tricuspid valve disease. 23 In addition, several important details (eg, time span from mitral surgery to TEER or details of such surgery) were not collected. While comprehensive, the application of nonparsimonious propensity scores may not account for all unmeasured differences, and residual confounding due to features that were not explicitly collected should be borne in mind.

In conclusion, TEER can be safely and effectively performed using the MitraClip device even in carefully selected patients with a clinical history of TEER or SMVR. Despite a lower yet still reasonable procedural success rate in patients with prior TEER, short‐ and long‐term outcomes appear similar, comparing patients naïve to mitral valve intervention with patients who had prior TEER or SMVR, even accounting for baseline differences. Whether results of TEER in such a challenging setting can be further ameliorated by combining TEER with other transcatheter repair techniques remains to be formally tested in dedicated clinical studies.

Sources of Funding

The GIOTTO is sponsored by the Italian Society of Invasive Cardiology, with an unrestricted grant by Abbott Vascular.

Disclosures

M.A. has received speaker fees from Abbott Structural Heart. G.B.‐Z. has consulted for Amarin, Balmed, Cardionovum, Crannmedical, Endocore Lab, Eukon, Guidotti, Innovheart, Meditrial, Microport, Opsens Medical, Terumo, and Translumina, outside the present work. The remaining authors have no disclosures to report.

Supporting information

Data S1

Tables S1–S3

References 24,25

This article was sent to Amgad Mentias, MD, Associate Editor, for review by expert referees, editorial decision, and final disposition.

Supplemental Material is available at https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/suppl/10.1161/JAHA.123.033605

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 11.

See Editorial by Dong et al.

References

- 1. Nishimura RA, Vahanian A, Eleid MF, Mack MJ. Mitral valve disease—current management and future challenges. Lancet. 2016;387:1324–1334. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00558-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Reid A, Blanke P, Bax JJ, Leipsic J. Multimodality imaging in valvular heart disease: how to use state‐of‐the‐art technology in daily practice. Eur Heart J. 2021;42:1912–1925. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ferruzzi GJ, Silverio A, Giordano A, Corcione N, Bellino M, Attisano T, Baldi C, Morello A, Biondi‐Zoccai G, Citro R, et al. Prognostic impact of mitral regurgitation before and after transcatheter aortic valve replacement in patients with severe low‐flow, low‐gradient aortic stenosis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2023;12:e029553. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.123.029553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Giordano A, Pepe M, Biondi‐Zoccai G, Corcione N, Finizio F, Ferraro P, Denti P, Popolo Rubbio A, Petronio S, Bartorelli AL, et al. Impact of coronary artery disease on outcome after transcatheter edge‐to‐edge mitral valve repair with the MitraClip system. Panminerva Med. 2023. May 31;65:443–453. doi: 10.23736/S0031-0808.23.04827-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. De Bonis M, Alfieri O, Dalrymple‐Hay M, Del Forno B, Dulguerov F, Dreyfus G. Mitral valve repair in degenerative mitral regurgitation: state of the art. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2017;60:386–393. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2017.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Davidson LJ, Davidson CJ. Transcatheter treatment of valvular heart disease: a review. JAMA. 2021;325:2480–2494. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.2133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stone GW, Lindenfeld J, Abraham WT, Kar S, Lim DS, Mishell JM, Whisenant B, Grayburn PA, Rinaldi M, Kapadia SR, et al. Transcatheter mitral‐valve repair in patients with heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2307–2318. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1806640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Iung B, Armoiry X, Vahanian A, Boutitie F, Mewton N, Trochu JN, Lefèvre T, Messika‐Zeitoun D, Guerin P, Cormier B, et al. Percutaneous repair or medical treatment for secondary mitral regurgitation: outcomes at 2 years. Eur J Heart Fail. 2019;21:1619–1627. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gaudino M, Ruel M, Obadia JF, De Bonis M, Puskas J, Biondi‐Zoccai G, Angiolillo DJ, Charlson M, Crea F, Taggart DP. Methodologic considerations on four cardiovascular interventions trials with contradictory results. Ann Thorac Surg. 2021;111:690–699. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2020.04.107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tamburino C, Immè S, Barbanti M, Mulè M, Pistritto AM, Aruta P, Cammalleri V, Scarabelli M, Mangiafico S, Scandura S, et al. Reduction of mitral valve regurgitation with Mitraclip® percutaneous system. Minerva Cardioangiol. 2010;58:589–598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rahhab Z, Lim DS, Little SH, Taramasso M, Kuwata S, Saccocci M, Tamburino C, Grasso C, Frerker C, Wißt T, et al. MitraClip after failed surgical mitral valve repair‐an international multicenter study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10:e019236. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.120.019236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mangieri A, Melillo F, Montalto C, Denti P, Praz F, Sala A, Winkel MG, Taramasso M, Tagliari AP, Fam NP, et al. Management and outcome of failed percutaneous edge‐to‐edge mitral valve plasty: insight from an international registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2022;15:411–422. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2021.11.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Corcione N, Ferraro P, Finizio F, Giordano A. Transcatheter management of combined mitral and aortic disease: dynamic duo or double trouble? Minerva Cardiol Angiol. 2021;69:117–121. doi: 10.23736/S2724-5683.20.05193-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Giordano A, Indolfi C, Ferraro P, Corcione N, Polimeno M, Messina S, Mongiardo A, Avellino R, Biondi‐Zoccai G, Frati G, et al. Implantation of more than one MitraClip in patients undergoing transcatheter mitral valve repair: friend or foe? J Cardiol Ther. 2014;1:133–137. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ferraro P, Biondi‐Zoccai G, Giordano A. Transcatheter mitral valve repair with MitraClip for significant mitral regurgitation long after heart transplantion. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;88:144–149. doi: 10.1002/ccd.26153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bedogni F, Testa L, Rubbio AP, Bianchi G, Grasso C, Scandura S, De Marco F, Tusa M, Denti P, Alfieri O, et al. Real‐world safety and efficacy of transcatheter mitral valve repair with MitraClip: thirty‐day results from the Italian Society of Interventional Cardiology (GIse) Registry of Transcatheter Treatment of Mitral Valve RegurgitaTiOn (GIOTTO). Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2020;21:1057–1062. doi: 10.1016/j.carrev.2020.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Giordano A, Ferraro P, Finizio F, Biondi‐Zoccai G, Denti P, Bedogni F, Rubbio AP, Petronio AS, Bartorelli AL, Mongiardo A, et al. Implantation of one, two or multiple MitraClip™ for transcatheter mitral valve repair: insights from a 1824‐patient multicenter study. Panminerva Med. 2022;64:1–8. doi: 10.23736/S0031-0808.21.04497-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Stone GW, Adams DH, Abraham WT, Kappetein AP, Généreux P, Vranckx P, Mehran R, Kuck KH, Leon MB, Piazza N, et al; Mitral Valve Academic Research Consortium (MVARC). Clinical trial design principles and endpoint definitions for transcatheter mitral valve repair and replacement: part 2: endpoint definitions: a consensus document from the Mitral Valve Academic Research Consortium. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:1878–1891. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Biondi‐Zoccai G, Romagnoli E, Agostoni P, Capodanno D, Castagno D, D'Ascenzo F, Sangiorgi G, Modena MG. Are propensity scores really superior to standard multivariable analysis? Contemp Clin Trials. 2011;32:731–740. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2011.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Waksman R, Rogers T. Transcatheter Mitral Valve Therapies. Wiley; 2021. doi: 10.1002/9781119763741 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Obadia JF, Messika‐Zeitoun D, Leurent G, Iung B, Bonnet G, Piriou N, Lefèvre T, Piot C, Rouleau F, Rouleau F, et al. Percutaneous repair or medical treatment for secondary mitral regurgitation. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2297–2306. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1805374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. von Bardeleben RS, Rogers JH, Mahoney P, Price MJ, Denti P, Maisano F, Rinaldi M, Rollefson WA, De Marco F, Chehab B, et al. Real‐world outcomes of fourth‐generation mitral transcatheter repair: 30‐day results from EXPAND G4. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2023;16:1463–1473. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2023.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Di Mauro M, Bonalumi G, Giambuzzi I, Masiero G, Tarantini G. Isolated tricuspid regurgitation: a new entity to face. Prevalence, prognosis and treatment of isolated tricuspid regurgitation [published online April 6, 2023]. Minerva Cardiol Angiol. doi: 10.23736/S2724-5683.23.06294-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bedogni F, Popolo Rubbio A, Grasso C, Adamo M, Denti P, Giordano A, Tusa M, Bianchi G, De Marco F, Bartorelli AL, et al. Italian Society of Interventional Cardiology (GIse) Registry of Transcatheter Treatment of Mitral Valve RegurgitaTiOn (GIOTTO): impact of valve disease aetiology and residual mitral regurgitation after MitraClip implantation. Eur J Heart Fail. 2021;23:1364–1376. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.2159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zoghbi WA, Adams D, Bonow RO, Enriquez‐Sarano M, Foster E, Grayburn PA, Hahn RT, Han Y, Hung J, Lang RM, et al. Recommendations for noninvasive evaluation of native valvular regurgitation: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography developed in collaboration with the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2017;30:303–371. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2017.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1

Tables S1–S3

References 24,25