Tinea capitis (scalp ringworm) is uncommon after puberty. When it occurs in adults the clinical features may be atypical and this may delay the diagnosis.1 Unless the possibility of dermatophyte infection is considered, unnecessary investigations may be performed and inappropriate treatment prescribed, as illustrated in the four cases described below.

Case reports

Case 1

A 45 year old Afro-Caribbean woman had had an itchy pustular eruption of the scalp with associated hair loss for several months. Her general practitioner had treated it unsuccessfully with neomycin and gramicidin ointment and oral flucloxacillin and metronidazole. During this period the woman underwent lymph node aspiration and chest radiography because she had an enlarged but painless cervical lymph node. Cytological examination showed a mixed population of lymphocytes, indicating reactive changes; in addition, the surgical house officer observed that the woman had “quite a nasty rash on her scalp.”

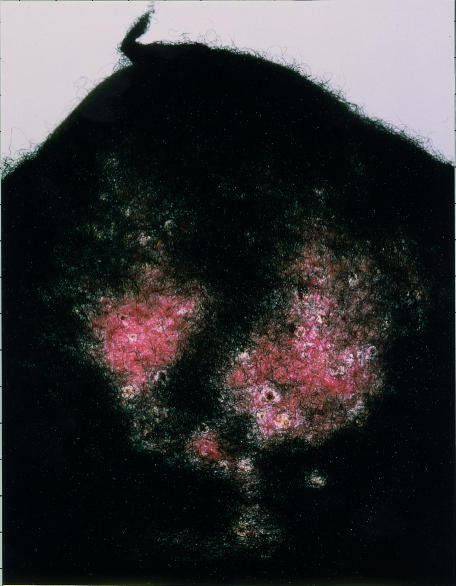

At the time of her referral to the dermatology clinic she had circumscribed areas of hair loss over the crown, with peripheral inflammation, pustules, and scaling (fig 1). Culture of bacterial swabs had negative results and a presumptive diagnosis of folliculitis decalvans (an idiopathic inflammatory scarring scalp disorder) was made. The areas of alopecia enlarged during a three month course of erythromycin (250 mg twice daily), and the patient needed to wear a wig. Hair plucks were sent for mycology tests but tinea capitis was considered unlikely and she was treated with isotretinoin (0.5 mg/kg daily). Four weeks later Trichophyton tonsurans was isolated and she responded well to three months' treatment with terbinafine (250 mg daily). The woman recalled that her 8 year old nephew had shared her bed just before the problem began; he had subsequently been treated for ringworm.

Figure 1.

Circumscribed areas of alopecia on the crown in case 1, with inflammation, pustules, and scaling

Case 2

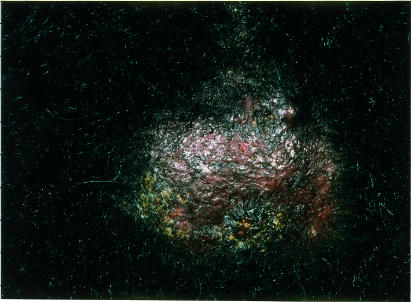

A 45 year old Afro-Caribbean woman had recurrent scabs and pustules on her scalp for several months. These did not respond to any one of several different antibiotics prescribed by the woman's general practitioner. Other family members were not affected. When the patient was seen in our department, she had an area of alopecia with pustules, crusts, and a boggy mass, which was clinically consistent with a kerion (fig 2). No pathogens were cultured from bacterial swabs, but T tonsurans was isolated from hair samples. The woman's symptoms resolved completely after six weeks' treatment with terbinafine (250 mg daily), and her hair gradually grew again over six months.

Figure 2.

Boggy mass on the scalp of patient 2, with overlying alopecia, pustules, and crusts

Case 3

A 35 year old Afro-Caribbean man attending our department with lichen planus of the trunk was noted to have a pustular scalp eruption with scarring alopecia. This condition did not respond to topical steroids and antifungal shampoos prescribed by the patient's general practitioner. A diagnosis of folliculitis decalvans was suspected. Culture of bacterial swabs was negative, but T tonsurans was detected in hair plucks sent for mycology tests. In recent months, his three children (aged 2, 7, and 9 years) had developed scaly patches on the body, and one had recently developed alopecia. The father's scalp condition cleared after one month's treatment with terbinafine (250 mg daily), but he was left with residual scarring. The children responded to oral griseofulvin.

Case 4

A 24 year old Afro-Caribbean man developed alopecia, pustules, and scaly patches on the scalp. These did not respond to treatment with a potent topical steroid and oral flucloxacillin. The patient was referred to the dermatology clinic. Further questioning revealed that his sister's children had been treated for ringworm a few months earlier. T tonsurans was isolated on culture, and the condition cleared completely after a one month course of terbinafine (250 mg daily).

Discussion

The quantity of fungistatic saturated fatty acids in sebum increases at puberty, and this is thought to explain the rarity of tinea capitis in adults.2 Dermatophytic colonisation of the scalp disappears at puberty.1–3 Colonisation by Pityrosporum orbiculare may interfere with dermatophyte contamination, and the thicker calibre of adult hair may protect against dermatophytic invasion.1 Tinea capitis in adults generally occurs in patients who are immunosuppressed and those infected with HIV.1 In immunocompetent adults, the clinical features are often atypical.1 The disease may resemble bacterial folliculitis, folliculitis decalvans, dissecting cellulitis, or the scarring related to lupus erythematosus.3,4

In recent years, the incidence of tinea capitis has increased in the United Kingdom, particularly among Afro-Caribbean children living in large cities.5,6 The mean age of patients is 5-6 years, and several siblings may be affected.5 The mean prevalence of culture positive tinea capitis in a 1996 school study from south east London was 2.5% (range 0%-12%).7 A further 4.9% of these children were asymptomatic carriers (range in classes 0%-47%). Many adults acquire tinea corporis from infected children, but tinea capitis is rare in adult contacts. It is recommended, however, that adult family members should be treated prophylactically with antifungal shampoos as they may be asymptomatic carriers of the dermatophyte.8

Between September 1997 and May 1998, we saw four cases of scalp ringworm in Afro-Caribbean adults. The delay in diagnosis was considerable in all these patients. This resulted in disfiguring hair loss, unnecessary invasive investigations, the development of scarring, and the spread of infection to other family members. We wish to alert colleagues to the possibility of tinea capitis in any adult with a patchy, inflammatory scalp disorder and to emphasise that mycological samples should be sent for laboratory analysis in all these patients.

Tinea capitis should be considered in all adults with a patchy inflammatory scalp disorder

Footnotes

Funding: None.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Cremer G, Bournerias I, Vandemeleubroucke E, Houin R, Revuz J. Tinea capitis in adults: misdiagnosis or reappearance? Dermatology. 1997;194:8–11. doi: 10.1159/000246048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rothman S, Smiljanic A, Shapiro AL, Weitkamp AW. The spontaneous cure of tinea capitis at puberty. J Invest Dermatol. 1947;8:81–98. doi: 10.1038/jid.1947.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pipkin JL. Tinea capitis in the adult and adolescent. Arch Dermatol Syphilol. 1952;66:9–40. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1952.01530260012002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sperling LC. Inflammatory tinea capitis (kerion) mimicking dissecting cellulitis. Occurrence in two adolescents. Int J Dermatol. 1991;30:190–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1991.tb03849.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buckley DA, Austin G, Armer J, Leeming JG, Moss C. Trichophyton tonsurans infection in Birmingham. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135(supp 47):21. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fuller LC, Child FC, Higgins EM. Tinea capitis in south-east London: an outbreak of Trichophyton tonsurans infection. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:139. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1997.tb08771.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hay RJ, Clayton YM, de Silva N, Midgley G, Rossor E. Tinea capitis in south-east London—a new pattern of infection with public health implications. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:955–958. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1996.d01-1101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Management of scalp ringworm. Drug Therap Bull. 1996;34:5–6. doi: 10.1136/dtb.1996.3415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]