Abstract

Introduction

a sizable proportion of the working population has a disability that is not visible. Many choose not to disclose this at work, particularly in educational workplaces where disability is underrepresented. A better understanding of the barriers and facilitators to disclosure is needed.

Sources of data

this scoping review is based on studies published in scientific journals.

Areas of agreement

the reasons underpinning disclosure are complex and emotive-in-nature. Both individual and socio-environmental factors influence this decision and process. Stigma and perceived discrimination are key barriers to disclosure and, conversely, personal agency a key enabler.

Areas of controversy

there is a growing trend of non-visible disabilities within the workplace, largely because of the increasing prevalence of mental ill health. Understanding the barriers and facilitators to disability disclosure is key to the provision of appropriate workplace support.

Growing points

our review shows that both individual and socio-environmental factors influence choice and experience of disclosure of non-visible disabilities in educational workplaces. Ongoing stigma and ableism in the workplace, in particular, strongly influence disabled employees’ decision to disclose (or not), to whom, how and when.

Areas timely for developing research

developing workplace interventions that can support employees with non-visible disabilities and key stakeholders during and beyond reasonable adjustments is imperative.

Keywords: disability disclosure, education, workplaces

Introduction

People with disabilities are one of the world’s largest minority groups.1 Unfortunately, many continue to be overlooked, including in workplace settings.2 In the UK, one in five working-age adults report a disability, chronic health condition or neurodivergence.3 Over the last decade, an increasing proportion of working-age adults report having a long-term health condition or disability. This upward trend is understood to be driven by increasing rates of ‘non-visible’ disabilities (e.g. mental health conditions).3,4 Non-visible disabilities refer to physical, mental or neurological conditions that pose challenges to an individual’s movement, senses or activities, but may not be immediately or obviously observed.4 Examples include mental health conditions, autism, sensory processing difficulties, cognitive impairment (e.g. dementia and traumatic brain injury), ‘non-visible’ physical health conditions (e.g. chronic pain, diabetes), hearing loss and low or restricted vision. Various terms have been used to describe this broad category of disabilities (including, hidden, invisible and non-visible disability). In the context of this study, we use the term non-visible disability in line with UK government guidance.5

Disabled people, including those with non-visible disability, continue to face significant and diverse barriers to full participation in employment and inclusion at work.4,6–8 The disability employment gap (i.e. the difference in employment rates between disabled and non-disabled people) is pervasive and exists globally.6 In the UK, for example, 52.7% of disabled people were employed in 2021, compared with 81% of non-disabled people.3 There exists a ‘disability disclosure gap’ in the workplace, which is also sizable and, for many, a significant barrier to the promotion of their health, inclusion at work and quality of life.9 A 2017 survey conducted in the USA observed that 30% of employees reported a disability, chronic health condition or neurodivergence, but only 3.2% disclosed this to their employer.10 Research from the UK shows that around 40%11,12 of disabled workers felt uncomfortable discussing their disability at work, reporting concerns regarding career progression and anticipated stigma.11

Traditionally, much of the literature on employment and disability has not focused on the disclosure of non-visible disability to employers.13 Particularly when employees are seeking workplace accommodations and adaptations.13 However, growing evidence highlights the personal and emotive nature of disability disclosure in the workplace, and there is an increased understanding of the personal and system-level barriers and facilitators. This knowledge demonstrates the importance of employees’ personal experience and impact of this on the disclosure process. Existing reviews have explored disclosure considerations, although this has typically been focused on specific conditions (e.g. mental ill health14) rather than across the wider category of non-visible disabilities. This approach misses shared experiences across non-visible disabilities and health conditions. The current review will help to address this gap in knowledge.

The education sector has been selected, as it is characterized by an underrepresentation of disabled employees as compared with other sectors. In the UK, 23% of working age people reported a disability.15 In contrast, only 6.3% of academics and 8.5% of non-academics, in 2021/2022, declared having a disability.16 The School Workforce Census in 2023 found that disability data were not obtained for over half of teachers (53%), with reporting rates found to be substantially lower than other protected characteristics (e.g. gender and age).17 Similar trends have been found internationally for education (e.g. Canada18 and Australia19).

Therefore, we focus our review on educational workplaces to explore disabled employees’ experiences, within an industry characterized by challenges surrounding inclusion and representation. Empirically, this review will contribute to our understanding of the barriers and facilitators to disability disclosure at work surrounding non-visible conditions uniquely and how these are experienced by disabled employees in educational workplaces.

Research questions/objectives

The research question is ‘What are the views and experiences of employees relating to non-visible disability disclosure in education workplaces?’. The study objectives are:

To explore the approaches and rationales of disability disclosure decisions.

To explore any perceived barriers and enablers of non-visible disability disclosure.

To explore disabled employees’ experiences during and following disclosure of a non-visible disability.

Methods

A scoping review was undertaken to map the literature on staff disability disclosure in education workplaces. The review is guided by scoping review aims and methodology as described by Arskey and O’Malley.20 Findings will identify any gaps in the literature and support the summary and dissemination of research to policymakers, employers and employees in education settings.

Search strategy

Searches were conducted in seven health and education databases including: MEDLINE, ERIC, PsycINFO, APA PsycArticles Full Text, Scopus, Embase and Educational Administration Abstracts. Google Scholar was also searched for any additional articles that may not have been listed in the selected databases. Research terms and strategies were established by the study team and refined with support from a university information specialist. Included articles were published between 2003 and 2023. The search language was limited to English. Further details and searching hits can be found in Appendix 1.

Study selection

The studies were selected based on inclusion and exclusion criteria determined a priori. Relevant articles were focused on the disclosure of non-visible disabilities as defined by the UK Parliament,4 where disclosure was the focus of the paper. Papers that included both visible and non-visible disabilities were excluded unless they separately reported on non-visible disability disclosure. Qualitative and quantitative studies were included. Study populations were employees aged 18 years or older and working in any department or job role within education employment settings. Education workplaces are defined as nursery/pre-school, children aged 4–18 (primary and secondary), college and further education, higher education, adult education, special educational settings. Non-visible disabilities are defined as a physical, mental or neurological condition(s) that are not visible, or are not immediately observable or apparent, and can limit or pose challenges to an individual’s movements, senses or activities.4 Disclosure is defined as ‘formally or informally telling colleagues, human resources, line manager, or organisation’. Although there is no strict delineation between visible/non-visible disabilities and individuals may experience a combination of both, to address our specific aims and objectives we excluded studies that did not have a central focus on non-visible health conditions. Reviews and grey literature were also excluded.

Charting the data

A data charting tool was created by following a guideline for scoping reviews developed by Pollock et al.21 MY established the data charting tool based on the research objectives, and J.H. and H.B. revised it. The tool included the following information: author, publication date and place, title, aim, study design, population, sample size, settings, types of disability, disclosure experiences and disclosure related outcomes.

Collating, summarizing and reporting results

Scoping reviews establish a thematic construction from the extant literature in a narrative and descriptive manner.22 A narrative review was conducted for knowledge synthesis. This approach enables the opportunity to explore relationships in the data and compare findings using different methodologies. The scoping review objectives guided the analysis of the included papers, focusing on several key aspects related to invisible disability disclosure. These aspects included formal and informal methods of disclosing non-visible disabilities, examining both positive and negative experiences associated with disability disclosure, identifying facilitators and barriers influencing the disclosure process and understanding the reasons behind individuals’ decisions to either disclose or not disclose their disabilities.

Results

Study inclusion

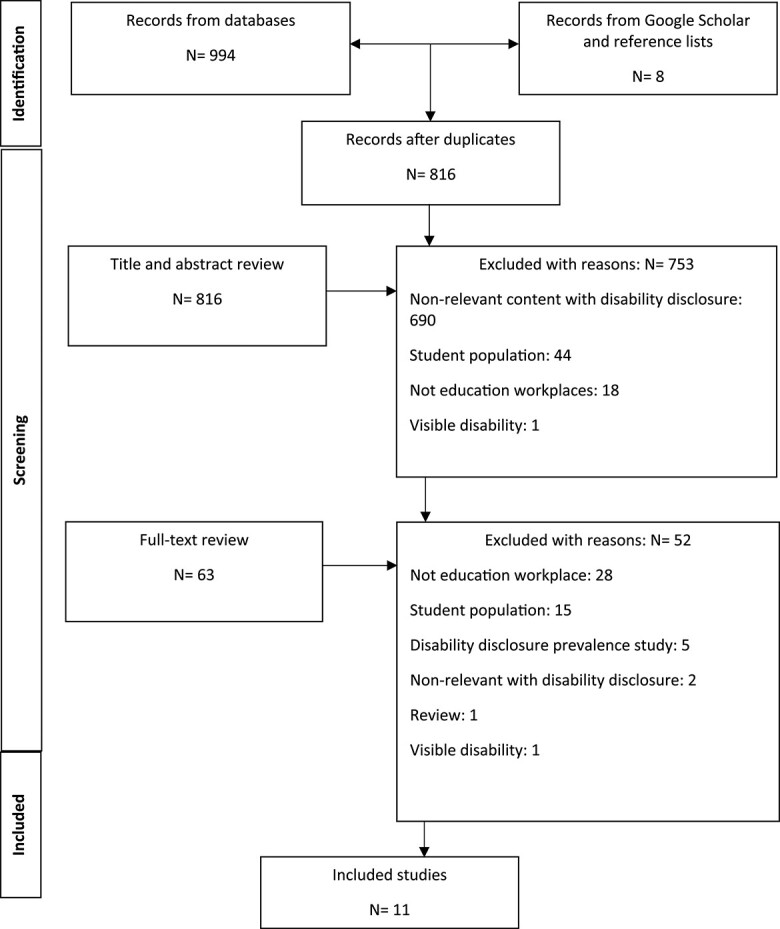

The initial search yielded a total of 2531 records from various databases, and an additional 106 records were identified through Google Scholar and reference lists, bringing the combined total to 2637 records. After removing duplicates, 1899 unique records remained for further assessment.

The title and abstract review were conducted on all 1899 records, and 1816 were excluded during this stage with reasons specified. The primary reasons for exclusion were non-relevant content with disability disclosure (1494 records), studies focusing on the student population (162 records) and studies not related to education workplaces (148 records). Additionally, 12 studies were excluded as it focused on individuals with visible disabilities.

Following the title and abstract review, 83 records were selected for full-text review. During this phase, 66 records were excluded based on predetermined criteria. The main reasons for exclusion at this stage were studies not related to education workplaces (28 records), studies focusing on the student population (17 records), studies focusing on the prevalence,7 studies not related to disability disclosure.6 Furthermore, seven studies one review focused on visible disabilities were excluded.

Ultimately, 17 studies met the inclusion criteria and included in the scoping review. Figure 1 represents the flow of screening process.

Fig. 1.

Search results and study selection.

Characteristics of included studies

The included studies were conducted across five countries: eight studies were from the USA,13,23–29 four from the UK,30–33 three from Canada,34–36 one from New Zealand37 and one from Germany.38 The publication years of the studies ranged from 2009 to 2023. Detailed characteristics of each study can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies

| Author Date Country |

Title | Aim | Study designs | Population | Sample size | Settings | Disability type | Disclosure type | Disclosure experience | Key outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Price et al. 2017 USA13 |

Disclosure of Mental Disability by College and University Faculty: The Negotiation of Accommodations, Supports, and Barriers |

To address the lack of research and understanding of the experiences of faculty members with mental disabilities in higher education | Survey | College and university members across USA | 267 | College or University | Mental disabilities | Formal and informal | Reasons for disclosing: • To request accommodations • To seek support • To reduce stigma and build trust Reasons for not disclosing: • Fear of negative consequences • Stigma • Difficulty finding supportive colleagues or supervisors • Lack of awareness about mental health issues Various positive and negative experiences reported in the disclosing process. |

Whilst most faculty with mental disabilities disclosed to colleagues, many lacked awareness of available accommodations and feared negative consequences. Disclosure experiences ranged from positive support to harmful bias, highlighting the need for better institutional support and inclusive workplaces. |

| Burns and Green 2019 USA23 |

Academic Librarians’ Experiences and Perceptions on Mental Illness Stigma and the Workplace |

To understand the stigma and address a gap in the literature about how academic librarians, many of whom are faculty on a tenure track, may experience mental illness stigma in their professional environments. |

Survey including free text questions | Academic librarians including 311 diagnosed with a mental illness | 549 | The survey was distributed amongst American Library Association Listservs. |

Mental health problems | Informal | Stigma • expected to ‘work harder’. • seen as suspicious and ‘taking advantage of the system’. • Fear of isolation |

Training and workshops can reduce stigma. |

| Pionke 2019 USA24 |

The Impact of Disbelief: On Being a Library Employee with a Disability |

To explores the accommodation process, its impact on the employee and the politics and psychology of disbelief and suspicion surrounding disability accommodation. |

Case study | A librarian | 1 | N/A | Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) |

Formal | • Stigma • Long procedure for accommodation Ableism |

Accommodation, from whichever angle you approach it, is not an easy thing. Done right, it leads to happier and more dedicated employees who work more efficiently. Done wrong, accommodations create resentment, a sense of betrayal and a devaluing of the self for the person who is asking for them. Whilst the law is clear that accommodations must be offered to people who ask for them, the law does not stipulate that employers have to understand, educate or embrace the person with a disability and that is the crux of the issue. |

| Cepeda M 2021 USA25 |

Thrice Unseen, Forever on Borrowed Time: Latina Feminist Reflections on Mental Disability and the Neoliberal Academy | To explore the experiences of multiply marginalized faculty members with mental disabilities in the neoliberal academy through a Latina feminist testimonial approach | Autoethnography | Professor | 1 | Williams College | Bipolar and PTSD | Formal | • Disclose for securing reasonable workplace accommodation and provide support for other colleagues with non-visible disabilities • Stigma • Fear of losing job • Pressure to prove herself and value at work. |

The study advocates for a more inclusive and supportive environment for faculty with non-visible disabilities, emphasizing the need for collective recognition and systemic change within academia to accommodate the diverse experiences of academics with mental health conditions and challenges. She urges for a shift in the discourse surrounding disability in higher education and calls for a more holistic approach to support the needs of faculty members with non-visible disabilities. |

| Green et al. 2020 USA26 |

Teaching and Researching with a Mental Health Diagnosis: Practices and Perspectives on Academic Ableism | To examine the experiences of academics with mental health diagnoses in the teaching and research process | Interviews | Academics with mental health diagnoses | 9 | University settings | Mental health conditions | Formal and informal | Reasons for disclosing: • Creating open dialogue and reducing stigma • Obtaining accommodations • Building trust and empathy Reasons for not disclosing: • Fear of discrimination and stereotyping • Maintaining personal privacy • Varied positive and negative experiences, including challenges in navigating stigma, accessing accommodations and maintaining academic productivity. Positive experiences include support and understanding by colleagues and students, personal empowerment and raising awareness. |

Emphasizes the need for a more inclusive and supportive environment for academics with mental health diagnoses in the academy. |

| England 2016 USA27 |

Being open in academia: A personal narrative of mental illness and disclosure | To present an autobiographical reflection on the decision to be open about the authors’ mental health status during all stages of her career, from diagnosis as a graduate student through the tenure process to her present state of working to attain full professor |

Narrative autobiography | A professor in Geography | 1 | Department of Geography, Miami University. | Bipolar | Formal | Prefer to disclose because of: • A belief needing support from friends and colleagues (safety) • A belief mental illness should be destigmatised. (stigma) |

Chronic mental illness is a challenge to disclose in academia. But, universities are becoming more aware of mental health issues and are providing counselling services and programmes to students and staff. |

| Clayton 2009 USA28 |

Teacher with a Learning Disability |

To explore disability experiences of a teacher who discloses a learning disability to her Principal | Case study | A teacher | 1 | The Northern City Public School | Learning disability | Formal | • Fear of losing job • Low performance is not because of lack of preparation |

It is important to disclose the disability. But there are many views on how disable teachers can continue the job. |

| Valle et al. 2010 USA29 |

The Disability Closet: Teachers with Learning Disabilities Evaluate the Risks and Benefits of ‘Coming Out’ |

To investigates the factors that influence whether teachers with learning disabilities (LD) choose to disclose their disability status within public school settings |

Interview | K-12 special education teacher and student teacher | 4 | N/A | Learning disability | Informal | • Stigma • Fear of losing status as an authority • Some disclosed to only students and their families. (to help others gain a deeper, more positive understanding of LD) |

The act of disclosing LD is a not an event, but a highly personal process, subject to a multitude of ongoing factors and always without finalization. The research reveals persistent misperceptions about LD amongst educators, leaving some teachers with LD to feel vulnerable and thus remain undisclosed. |

| Wood and Happe 2023 UK30 |

What are the views and experiences of autistic teachers? Findings from an online survey in the UK |

To discover views and experiences of autistic people working in an education role in the school sector in the UK |

Survey (analysis of free text questions) | School staff | 149 | UK | Autism | N/A | • Fear of losing job • Some lost their job • Ableism (prejudice) • Stigma • Positive and supportive experience |

The present findings suggest that autistic staff working in an education role in schools in the UK experience several impediments to their effective and successful employment in the sector. Some participants have positive experiences after disclosing their autism diagnosis, becoming valued members of the school community. |

| Marshall et al. 2020 UK31 |

“What should I say to my employer… if anything?”- My disability disclosure dilemma |

To explore the key issues surrounding teacher/staff disability disclosures in the UK’s further education (FE) sector |

Semi-structured interviews | Staff | 15 | Further Education setting in the Southeast of England | Non-visible disabilities including mental conditions | N/A | • Disclosing is anxious, distressing. • Seen as incompetence. • Seen as deficit |

Fear of stigma and negative consequences leads most FE teachers to not disclose disabilities. Teachers with disabilities fear discrimination, lack of promotion or job loss if they disclose. |

| Horton and Tucker 2014 UK32 |

Disabilities in academic workplaces: experiences of human and physical geographers |

To explore how diverse disabilities intersect with academic careers, lifestyles and workplaces, focusing on some common disciplinary and institutional spaces of human and physical geography. |

Survey with free text questions | Academic staff | 75 | Respondents from different countries | Mental health conditions | Informal | • Stigma • Competitive working environment • Having clout helps to disclose disabilities • Fear of job lost |

There is a need to support those with mental health conditions in academic workplaces. They mostly encountered issues including isolation, lack of support, distress, pressure, low self-esteem, fear of appearing ‘weak’—overlapped with the often-undisclosed experiences of many ‘non-disabled’ colleagues. |

| Hiscock and Leigh 2020 UK33 |

Exploring perceptions of and supporting dyslexia in teachers in higher education in STEM | To explore the perceptions of dyslexia and the experiences of teachers with dyslexia in higher education in STEM | Mixed methods, online survey and interviews | Teachers in higher education | 115 | Higher education institutions | Dyslexia | Informal | Disclosing dyslexia to assess students and colleagues’ perceptions. Positives: • Student acceptance • More inclusive and supportive learning environment • Normalizing disability • Encouraging others Negatives: • Stigma • Fear of judgement or negative consequences |

Teachers with dyslexia find acceptance from students and colleagues when being open about their diagnosis. Openness and inclusive practices foster trust and understanding, making higher education more equitable for academics with dyslexia. |

| Skogen 2012 Canada34 |

‘Coming into Presence’ as Mentally Ill in Academia: A New Logic of Emancipation |

To discusses the impact of stigma on a professor’s decision to either disclose or conceal her illness. |

Autoethnography | Professor | 1 | University of Alberta | Bipolar | Informal | • Sigma • Fear • Shame |

Disclosing a severe mental health issue is a challenging process because of fear, stigma and shame. |

| Oud 2019 Canada35 |

Systemic Workplace Barriers for Academic Librarians with Disabilities |

To explore the workplace experiences of librarians with disabilities working in university libraries in Canada |

Interviews | Librarians | 10 | Canadian university libraries | Non-visible disabilities including mental conditions | Formal and informal | • Disclose as a coping strategy or increasing awareness of disability. • Not disclose because of stigma fear of job or promotion lost. • Mixed positive and negative experiences on legal work accommodations |

The main barriers reported in the study were related to a lack of awareness or ill-informed view of disability, including an assumption that everyone in the workplace is nondisabled and negative stereotypes of people with disabilities as lazy and less productive at work. |

| Morrison 2019 Canada36 |

(Un)Reasonable, (Un)Necessary and (In)Appropriate: Biographic Mediation of Neurodivergence in Academic Accommodations |

To critically examine the institutional demands for personal disclosure and the bureaucratic processes involved in securing workplace accommodations for disabled faculty members in higher education | Autoethnography | Associate Professor in English at the University of Waterloo | 1 | University | ADHD | Informal | • Disclosing to promote a positive shift in the disclosure of disabilities • The extensive and complex nature of the verification process • The fear of being split into an ‘otherwise qualified’ |

The study explores the challenges faced by disabled faculty in higher education, focusing on the difficulties of disclosure and accommodation. It emphasizes the dehumanizing verification process, bureaucratic emphasis on essential duties and conflicts between institutions and individuals in securing accommodations. The study advocates for a more holistic approach to rebuilding higher education to support access for disabled individuals. |

| Wright and Kaupins 2018 New Zealand37 |

‘What About Us?’ Exploring What It Means to Be a Management Educator With Asperger’s Syndrome |

To explore Asperger’s Syndrome impact on teaching and learning from the instructor’s perspective |

Case study - Interview | Professor | 1 | Boise State University | Asperger’s syndrome (AS) |

Prefer not disclose | • No disclosure but fight with that | AS need not be seen as a disability or deficiency in the management classroom. Using cognitive and behavioural techniques, individuals with AS can effectively manage their symptoms, leading to enhanced teaching delivery and assessment methods. |

| Sanchez 2023 Germany38 |

Decisions, practices and experiences of disclosure by academics with invisible disabilities at German universities | To examine the decisions, practices and experiences of disclosure amongst academics with non-visible disabilities at German universities | Interviews | Academics with non-visible disabilities at German universities | 16 | University settings | Non- visible disabilities including mental conditions | N/A | Prefer not to disclose because of: • Fear of stigma and discrimination • Concerns about professional competence • Maintaining personal privacy and boundaries |

Academics with non-visible disabilities often feel pressured to present themselves as academically capable and competent individuals, selectively sharing and controlling disability information as an anti-stigma strategy within the abled-normative academia. Emphasizes the need for a supportive and inclusive environment for academics with non-visible disabilities in German universities. |

The study designs employed in these included studies were diverse, and included five qualitative interviews,26,29,31,35,38 four surveys,13,23,30,32 three case studies,24,28,37 three autoethnography,25,34,36 an autobiography27 and a mixed-method.33 Sample sizes varied significantly, ranging from 1 to 549 participants. These studies explored education settings such as universities and colleges,13,25–27,32–34,36–38 public schools28–31 and academic libraries (i.e. in higher education settings).23,24,35 The occupational groups examined included university or college members13 including professors,25,27,28,34,36,37 academics,26,38 lecturers,32 librarians,23,24,35 teachers28,29,33 and school staff.30,31 The studies focused on various non-visible disabilities, including mental health conditions,13,23–27,31,32,34,35,38 learning disabilities and differences28,29,33,36, Autism30 and Asperger’s syndrome.37

Approaches and rationales of non-visible disability disclosure

Across the 17 studies, 12 explored the approaches used by employees in educational workplaces to disclose their disability.13,23–29,32,33,35,36 Observed across the studies, the employed approaches used for disability disclosure were diverse, included a variety of stakeholders (line managers, co-workers, students and their parents) and did not always include interacting with established human resource (HR) and/or in-house occupational health (OH) systems. We categorized these approaches as either formal13,24–28,35 or informal13,23,26,29,32–36 forms of disability disclosure at work.

We define a ‘formal’ disclosure approach as one that refers to explicitly informing the employer or institution about one’s disability through official channels or documentation. For employees in educational workplace settings, this process was characterized by following a formal HR procedure8 and a formal meeting with management13,25,26,28,35 to discuss workplace accommodations and adaptations. In contrast, we define informal disclosure as sharing information about one’s disability outside of formal HR/OH systems. For employees in educational workplace settings, this disclosure process was characterized by selectively revealing their disabilities to trusted colleagues, students and their parents.13,23,26,27,29,32,35,36

Ten studies explore the rationales for disclosure amongst employees in educational workplace settings.13,24–29,32,33,35 The rationale discussed were multifaceted (influenced by both current and past experiences) and often characterized by instrumental- and/or emotional-directed coping strategies. The main reported reason for formally disclosing a disability to an employer was to access reasonable workplace accommodations.13,24–26,35 Across both formal and informal forms of disclosure, the other rationales discussed for disability disclosure by employees in education workplaces were the need/want for peer and emotional support13,24,26,28,32 at work, and the desire to raise awareness and promote increased inclusion within and across their work environment.13,25,27,33–35 These stated rationales were characterized across formal and informal forms of disclosure. This suggests, perhaps, that in educational workplaces, employees’ disclosure of non-visible disability (within and outside HR systems) is important beyond just accessing reasonable adjustments and securing instrumental needs. It may also yield psychological value through increased opportunities for emotional support, and positive feelings associated with being agents of positive change.

A stated rationale, unique to formal disclosure, was reporting a past positive experience in disclosing their disability in the workplace.35 This highlights the importance of considering employees culmination of experiences in the workplace, both past and present, and how this may influence decision-making process and employee behaviours regarding disability disclosure. Potentially unique to employees in educational workplace settings—who chose not to formally declare their disability to their employer—was the nature of the disability itself,23,29 and their perceptions regarding its attached social stigma and anticipated workplace discrimination post-disclosure.

Employee experiences during and following disability disclosure.

We observed that the lived experience of disabled employees within educational workplace settings, during and following, disability disclosure was complex, and typically characterized by both positive13,23,27,30,33,35,36,38 and/or negative experiences.13,23–25,27,30,32,34–36,38 Such experiences were explored in 1213,23–25,27,30,32–36,38 of the 17 studies. Although findings were mixed, the studies predominantly revealed negative experiences associated with disability disclosure, rather than positive ones.

Among those studies that explored positive experiences13,23,25,27,30,33,35,36,38 during or following disclosure, they were—typically—characterized by disabled employees feeling as though their instrumental and emotional needs were actively considered and addressed by their workplace. This included employees in educational workplace settings considering that their act of disclosure resulted in workplace accommodations and adaptations that met their expressed needs,13,23,27,30,33 and were implemented in a timely and responsive manner with the necessary resources.13,35 Disabled employees who felt they received support and understanding from their supervisor and colleagues13,23,27,33 expressed this as a positive experience. In the study by Wood and Happe,30 some (but not all) participants who disclosed their autism at work felt as though they received better understanding and appreciation from the school community and families, leading to a more autism-friendly and accommodating work environment. In England’s27 (2002) autobiographical study, a professor reported positive experiences following formal disclosure because of support obtained from colleagues, and the instrumental support from a professional mentor in obtaining requested reasonable adjustments and gaining emotional support. Price et al. conducted a survey of college and university staff with a mental health condition across the USA. They found participants reported varied levels of support from their managers and colleagues with a generally positive reception of their disclosure.13 A higher number of people reported positive experiences with colleagues and chairs, whereas a lower number reported positive experiences with HRs.13 Hiscock and Leigh33 found support after dyslexia disclosure encompassed positive colleagues and student feedback including their understanding and perceptions towards teaching with dyslexia. This positive feedback led to an inclusive and supportive working environment. These positive experiences amongst disabled employees in educational workplace settings appear to be shaped by two key considerations. First, the importance of workplace accommodations and reasonable adjustments tailored to the unique needs and expressed wishes of the disabled employee, which are enacted upon by the organization in a purposeful, timely and responsive manner. Second, the importance of also considering what job resources (e.g. mentoring and coaching) and forms of social support (e.g. peer support network, sensitive and informed line managers) can support the disabled employee—during and following—their disability disclosure.

Many of the reviewed studies explored negative experiences24,30,32,34,35 for disabled employees during and beyond disability disclosure. These negative experiences were characterized by challenges in accessing and obtaining requested reasonable adjustments.24,35 In particular, some of the key challenges highlighted included a perceived reluctance of supervisors or management to provide requested workplace accommodations (particularly changes in working patterns and hours35), with lengthy waits for adjustments that were not necessarily aligned with what had been agreed.24 In Pionke’s24 case study the employee felt the wider context of the implemented workplace accommodation (e.g. access to an enclosed office) was not considered. Whilst they were provided with an enclosed office, it was physically located away from her department, resulting in decreased access to social and professional networks and, in turn, increased feelings of social isolation. In this same case, the disabled employee felt disenfranchised and ‘othered’ by management concealing her disability without her consent following her disclosure. A common experience observed across reviewed studies for disabled employees in educational workplace settings was encountering stigma and perceived discrimination following their disclosure from both colleagues34 and managers.30,32 Often leading to feelings of invalidation30,32 and ‘othering’,24 feeling insecure or replaceable in their professional roles30,32 or being fearful or risk to their career or reputation by disclosing.34

Perceived barriers and enablers of invisible disability disclosure

‘Enablers’ of disability disclosure varied amongst employees with non-visible disabilities. The reasons for disclosure were often influenced by their perceived work environment, support systems and personal goals. Some disabled employees in the reviewed studies chose to disclose to raise awareness about disability issues and to advocate for better conditions for individuals with disabilities in the workplace.13,26,27,34,35 Believing that visibility and openness regarding non-visible disabilities may help to generate a more inclusive and supportive workplace culture. Disabled employees who felt supported, respected and secure in their jobs were more likely to disclose.13,23,26,30,32,35,36 A positive and inclusive work environment encouraged employees to feel comfortable sharing information about their disabilities.13,23,30,32 Some participants selectively disclosed their disabilities to a few co-workers they trusted and felt safe with.35 Selective disclosure allowed them to seek support and assistance without exposing themselves to potential risks that were perceived to be associated with broader or formal forms of disclosure. For some, disclosing their disability was a coping strategy to ensure that colleagues would understand their needs and potential challenges better, reducing misunderstandings or negative judgements.13,23,26,32,33,35,37,38 In several studies, participants felt sharing their diagnosis or health-related experiences with colleagues, students and parents would provide positive role models for others.30,34 They hoped to break stereotypes about non-visible disabilities and show that success and disability are not mutually exclusive. In a few studies,25,26 participants also believed that disclosing their disability helped reduce stigma related to their disability and build trust and empathy with institution,25,26 HRs.26 Price’s13 study suggested that certain and clear disability disclosure processes may encourage faculty members to share their mental health disabilities with, particularly, HRs and managers. In certain cases, participants chose to disclose their disabilities, particularly their neurodiversity (e.g. autism) and specific learning differences (e.g. dyslexia), only to students and their families rather than their employer.29,30 This disclosure was driven by a desire to promote a deeper, more positive understanding of neurodiversity and specific learning differences, with the intention that this would assist others in similar situations. Job status also impacted on disability disclosure, since those with greater status and seniority felt more secure about their job and, therefore, more confident to disclose a disability.32

‘Barriers’ to disability disclosure were prevalent and, broadly, influenced by individuals’ want to keep their disabilities hidden because of fear of stigma, discrimination and ableism. One of the primary barriers to disability disclosure was the fear of negative consequences to career or professional reputation because of anticipated stigma and discrimination.13,25,26,35,36,38 Across the reviewed studies disabled employees reported being fearful of losing their job or being passed over for promotion25,28,30,32,35 or fear of losing status and authority29 as key barriers to disclosing. For example, Horton and Tucker32 found that early career academics and researchers expressed insecurity and feelings of replaceability within their departments and institutions.

Fear of isolation in the working environment was also another reason to be reluctant to disclose, which may result from poorly implemented reasonable adjustments3 or socially by feeling ‘othered’ through or by this declaration process.24,36 In several studies, the complexity, length and cumbersome nature of access reasonable adjustments and workplace accommodations were a key barrier to disability disclosure.23,24,31,32,35,36,38 In one study amongst librarians, many were reluctant—in particular—that gaining access to accommodation requests was contingent on the individual manager, with some reluctant to implement any discussed adjustments.35 Previous negative experiences with disability disclosure29,31,35, competitive working environments,32 the fear of being seen to be taking advantage of system23 and the fear of being viewed as incompetent25,31,35,36,38 were other reasons for not disclosing disabilities in education workplaces. In a case study,37 the participant did not see a pressing need to disclose his disability. They felt that their condition was not debilitating enough to warrant mentioning and preferred to manage their condition privately without seeking workplace accommodations. Maintaining personal privacy and boundaries was reported as reasons for not disclosing.26,38 Several studies13,31,38 found that employees in education settings found it easier to disclose and discuss a physical disability that was visually apparent, as opposed to disabilities that were not visible to others.

Discussion and conclusion

The reasons underpinning disclosure are complex and emotive-in-nature. In educational workplace settings, there exists a disability disclosure gap.16 As non-visible disabilities can often be concealed by employees, the process of declaring and discussing this individual experience or health condition is highly sensitive39 and, in turn, poses unique challenges to organizational leadership.9 For example, this impacts on how employing organizations support open discussions surrounding inclusion, which, in turn, impairs opportunities to providing practical support regarding reasonable adjustments tailored to individual wants and needs.9 There is a growing trend of non-visible disabilities within the workplace. It is imperative, therefore, to understand the barriers and facilitators to disability disclosure within workplace settings. Particularly, in industries where disability is under-represented.

This scoping review highlights the complex nature of disclosure of a non-visible disability within educational workplace settings. This complex and multifaceted decision-making process is not unique to educational workplace settings but appears to be uniquely experienced across the community of employees with non-visible disabilities.40–43 Our review observes both individual and socio-environmental factors appear to influence this decision and process. Ongoing stigma and ableism in the workplace strongly underpin disabled employees’ decision to disclose (or not), to whom, how and when. These are prevalent themes observed across conditions,41 as well as across sectors and workplaces44.

We conclude that the disability disclosure dilemma—that is the decision to disclose either formally to the organization through HRs systems or management or informally to co-workers—appears to include a personal process of risk evaluation shaped by ableism considerations. This observation is in line with the emerging literature,40,43 which suggests that the decision to disclose includes careful consideration and balancing of perceived risks and costs in comparison to gains and benefits.45 When gains and benefits (e.g. increased support and understanding, access to reasonable adjustments) appear to outweigh the potential risks and costs (e.g. feeling undervalued or insecure in their job or position) to the disabled employee, it is likely this will facilitate and enable disclosure (either formally or informally).

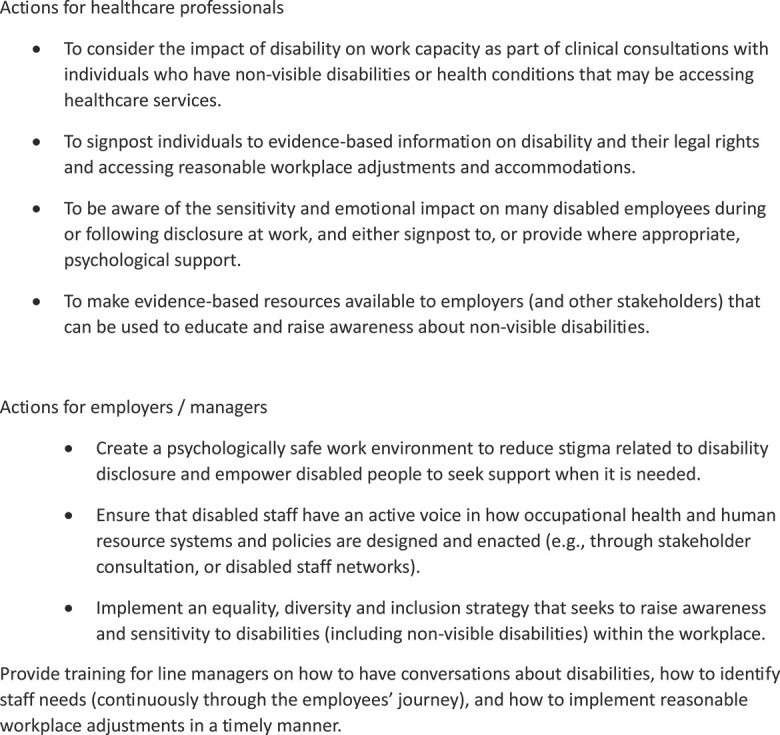

This process of risk evaluation is dynamic and influenced by both past experiences, but also by the changes in the individual’s role in the organization (e.g. becoming more senior) or health condition (e.g. fluctuations or increased severity), changes in management perceptions and practices (e.g. line manager sensitivity training), evolving working conditions and culture (e.g. flexible work schedules) and availability of support networks (e.g. disabled staff network). Efforts in the education sector to facilitate an inclusive environment for individuals with a non-visible disability have typically focused on students, rather staff.2,46 Therefore, to ensure educational workplaces are inclusive and supportive of disability requires initiatives and supports that target both students and staff collectively and equitably. Both healthcare professionals and employers can play an important role in tackling low levels of disability disclosure in education settings (particularly those with non-visible disabilities) and supporting those who choose to disclose and seek workplace adjustments. Recommendations are outlined in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Recommendations for practice.

Author contributions

Juliet Hassard (Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing), Mehmet Yildrim (Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft), Louise Thomson (Conceptualization, Writing—review & editing) and Holly Blake (Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Writing—review & editing)

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest.

Data availability

The authors confirmed that the data supporting the findings of the study are available within the article and its supplementary materials.

Supplementary Material

A. Appendix 1

Searching strategy

OVID including Embase, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, APA PsycArticles Full Text

| # | Query | Results from November 8, 2023 |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | ((invisible or hidden or undisclosed or non-apparent or unseen or concealed or non-evident or mental) adj5 (disability)).mp. [mp = ti, ab, hw, tn, ot, dm, mf, dv, kf, fx, dq, bt, nm, ox, px, rx, an, ui, sy, ux, mx, tc, id, tm, tx, sh, ct] | 1206 |

| 2 | exp disability/ | 187 750 |

| 3 | 1 or 2 | 188 841 |

| 4 | workplace.mp. [mp = ti, ab, hw, tn, ot, dm, mf, dv, kf, fx, dq, bt, nm, ox, px, rx, an, ui, sy, ux, mx, tc, id, tm, tx, sh, ct] | 210 266 |

| 5 | (‘education workplace’ or ‘academic institution’ or ‘university’ or ‘college’ or ‘higher education’ ‘faculty’ or ‘academic setting’ or ‘educational environment’).mp. [mp = ti, ab, hw, tn, ot, dm, mf, dv, kf, fx, dq, bt, nm, ox, px, rx, an, ui, sy, ux, mx, tc, id, tm, tx, sh, ct] | 2 351 067 |

| 6 | 4 or 5 | 2 539 710 |

| 7 | (‘employee perspectives’ or ‘worker experiences’ or ‘faculty views’ or ‘staff attitudes’ or ‘academic perceptions’ or ‘professional experiences’ or ‘teacher views’).mp. [mp = ti, ab, hw, tn, ot, dm, mf, dv, kf, fx, dq, bt, nm, ox, px, rx, an, ui, sy, ux, mx, tc, id, tm, tx, sh, ct] | 7385 |

| 8 | (‘barriers’ or ‘facilitators’ or ‘experiences’ or ‘views’ or ‘difficulties’ or ‘challenges’ ‘ableism’).mp. [mp = ti, ab, hw, tn, ot, dm, mf, dv, kf, fx, dq, bt, nm, ox, px, rx, an, ui, sy, ux, mx, tc, id, tm, tx, sh, ct] | 3 274 558 |

| 9 | 7 or 8 | 3 277 011 |

| 10 | 3 and 6 and 9 | 1633 |

EBSCOhost including ERIC and Educational Administration Abstracts

| # | Query | Results from EBSCOhost on November 8, 2023 |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Disability | 166 569 |

| 2 | disclosure or revealing or reporting or declare or sharing | 89 828 |

| 3 | education or academic or university or college or ‘higher education’ or teacher or lecturer or professor or staff | 2 979 838 |

| 4 | barrier or facilitator or experience or view or difficulty or challenge or accommodation or ableism | 869 139 |

| 5 | invisible or mental or unseen or hidden or undisclosed or concealed or non-apparent or non-evident | 162 033 |

| 6 | 1 and 2 and 3 and 4 and 5 | 308 |

Scopus

| # | Query | Results from Scopus on November 8, 2023 |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | ‘Disability disclosure’ OR ‘disability revealing’ OR ‘disability reporting’ OR ‘disability declare’ OR ‘disability sharing’ | 832 |

| 2 | (education OR academic OR university OR college OR ‘higher education’ OR teacher OR lecturer OR professor OR staff) | 57 577 642 |

| 3 | (barrier OR facilitator OR experience OR view OR difficulty OR challenge OR accommodation OR ableism) | 22 938 932 |

| 4 | (invisible OR mental OR unseen OR hidden OR undisclosed OR concealed OR non-apparent OR non-evident) | 4 620 914 |

| 5 | 1 and 2 and 3 and 4 | 590 |

Google Scholar (screened the first 100 articles), searched through a tool (Publish or Perish 8)

| # | Query | Results from Google Scholar on November 8, 2023 |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | ‘disability disclosure’ OR ‘disclosure experiences’ OR ‘barriers to disability disclosure’ OR ‘facilitators to disability disclosure’ AND ‘invisible disabilities’ OR ‘mental disabilities’ AND ‘education workplaces’ OR ‘higher education’ AND ‘staff’ OR ‘academic staff’ | 100 |

Contributor Information

Juliet Hassard, Queen’s Business School, Queen’s University Belfast, Belfast, BT9 5EE, UK.

Mehmet Yildrim, School of Health Sciences, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, NG7 2RD, UK.

Louise Thomson, School of Medicine, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, NG7 2DR, UK.

Holly Blake, School of Health Sciences, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, NG7 2RD, UK; NIHR Nottingham Biomedical Research Centre, Nottingham, NG7 2RD, UK.

References

- 1. Friedman HH, Lopez-Pumarejo T, Friedman LW. The largest minority group--the disabled (August 1, 06). B> Quest 2006:1–9. https://ssrn.com/abstract=2345457. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Officer A, Posarac A. World Health Organ. World Report on Disability World Health Organ, Geneva, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Taylor H, Florisson R, Wilkes M, et al. The Changing Workplace: Enabling Disability-Inclusive Hybrid Working, the Work Foundation, Lancaster, 2022.

- 4. Kelly R, Mutebi N, Ruttenberg D, et al. Invisible Disabilities in Education and Employment, UK Parliament Post, London, 2023.

- 5. Disability Unit . Living with Non-Visible Disabilities [Internet]. Cabinet Office, London, 2020. https://disabilityunit.blog.gov.uk/2020/12/17/living-with-non-visible-disabilities/ (17 January 2024, date last accessed).

- 6. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Food and Agriculture Organization . OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2022–2031. Paris Cedex, France: Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), OECD publishing, Paris, 2022,274 (OECD agricultural outlook).

- 7. Purc-Stephenson RJ, Jones SK, Ferguson CL. “Forget about the glass ceiling, I’m stuck in a glass box”: a meta-ethnography of work participation for persons with physical disabilities. J Vocat Rehabil 2017;46:49–65. 10.3233/JVR-160842. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hogan A, Kyaw-Myint SM, Harris D, et al. Workforce participation barriers for people with disability. Int J Disabil Manag 2012;7:1–9. 10.1017/idm.2012.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Santuzzi AM, Waltz PR, Finkelstein LM, et al. Invisible disabilities: unique challenges for employees and organizations. Ind Organ Psychol 2014;7:204–19. 10.1111/iops.12134. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sherbin L, Kennedy JT, Jain-Link P, Ihezie K. Disabilities and Inclusion US Findings [Internet]. coqual.org; Centre for Talent and Innovation Publishing, New York, 2017. http://www.coqual.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/CoqualDisabilitiesInclusion_KeyFindings090720.pdf (17 January 2024, date last accessed).

- 11. End the Awkward [Internet] . SCOPE - Equality for Disabled People, London. https://www.scope.org.uk/campaigns/end-the-awkward/ (17 January 2024, date last accessed).

- 12. Wales T. Disability and ‘hidden’ impairments in the workplace. Cymru Survey Report. Wales Trades Union Congress; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Price M, Salzer MS, O’Shea A, et al. Disclosure of mental disability by college and university faculty: the negotiation of accommodations, supports, and barriers. Disabil Stud Q 2017;37(2). 10.18061/dsq.v37i2.5487. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Brohan E, Henderson C, Wheat K, et al. Systematic review of beliefs, behaviours and influencing factors associated with disclosure of a mental health problem in the workplace. BMC Psychiatry 2012;12:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kirk-Wade E. UK Disability Statistics: Prevalence and Life Experiences. House of Commons Library, London, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Higher Education Staff Data (HESA) Table 27 - All Staff (Excluding Atypical) by Personal Characteristics 2014/15 to 2021/22. HESA, Cheltenham. [Internet]. https://www.hesa.ac.uk/data-and-analysis/staff/table-27 (17 January 2024, date last accessed).

- 17. Department for Education. School Workforce Census Guide 2023 [Internet]. Department for Education, London, 2023. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1168140/School_workforce_census_guide_2023.pdf (19 January 2024, date last accessed).

- 18. Wolbring G, Lillywhite A. Equity/equality, diversity, and inclusion (EDI) in universities: the case of disabled people. Societies (Basel) 2021;11:49. 10.3390/soc11020049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mellifont D, Smith-Merry J, Dickinson H, et al. The ableism elephant in the academy: a study examining academia as informed by Australian scholars with lived experience. Disabil Soc 2019;34:1180–99. 10.1080/09687599.2019.1602510. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005;8:19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pollock D, Peters MDJ, Khalil H, et al. Recommendations for the extraction, analysis, and presentation of results in scoping reviews. JBI Evid Synth 2022;21:520–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Aromataris E, Stern C, Lockwood C, et al. JBI series paper 2: tailored evidence synthesis approaches are required to answer diverse questions: a pragmatic evidence synthesis toolkit from JBI. J Clin Epidemiol 2022;150:196–202. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2022.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Burns E, Green K. Academic librarians’ experiences and perceptions on mental illness stigma and the workplace. Coll Res Libr 2019;80:638–57. 10.5860/crl.80.5.638. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pionke JJ. The impact of disbelief: on being a library employee with a disability. Libr Trends 2019;67:423–35. 10.1353/lib.2019.0004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cepeda ME. Thrice unseen, forever on borrowed time. South Atl Q 2021;120:301–20. 10.1215/00382876-8916046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Green A, Dura L, Harris P, et al. Teaching and researching with a mental health diagnosis: practices and perspectives on academic ableism. Rhetoric Health Med 2020;3:3. 10.5744/rhm.2020.1010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. England MR. Being open in academia: a personal narrative of mental illness and disclosure. Can Geogr 2016;60:226–31. 10.1111/cag.12270. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Clayton JK. Teacher with a learning disability: legal issues and district approach. J Cases Educ Leadership 2009;12:1–7. 10.1177/1555458909336842. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Valle JW, Solis S, Volpitta D, et al. The disability closet: teachers with learning disabilities evaluate the risks and benefits of coming out. Equity Excell Educ 2010;37:4–17. 10.1080/10665680490422070. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wood R, Happé F. What are the views and experiences of autistic teachers? Findings from an online survey in the UK. Disabil Soc. 2023;38:47–72. 10.1080/09687599.2021.1916888. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Marshall JE, Fearon C, Highwood M, et al. What should I say to my employer… if anything? -my disability disclosure dilemma. Int J Educ Manag 2020;34:1105–17. 10.1108/IJEM-01-2020-0028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Horton J, Tucker F. Disabilities in academic workplaces: experiences of human and physical geographers. Trans Inst Br Geogr 2014;39:76–89. 10.1111/tran.12009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hiscock J, Leigh J. Exploring perceptions of and supporting dyslexia in teachers in higher education in STEM. Innov Educ Teach Int 2020;57:714–23. 10.1080/14703297.2020.1764377. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Skogen R. Coming into presence as mentally ill in academia: a new logic of emancipation. Harv Educ Rev 2012;82:491–510. 10.17763/haer.82.4.u1m8g0052212pjh8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Oud J. Systemic workplace barriers for academic librarians with disabilities. Coll Res Libr 2019;80:169–94. 10.5860/crl.80.2.169. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Morrison A. (Un)reasonable, (un)necessary, and (in)appropriate: biographic mediation of neurodivergence in academic accommodations. Biography 2019; 42: 693–719. 10.1353/bio.2019.0066. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wright S, Kaupins G. “What about us?” exploring what it means to be a management educator with Asperger’s syndrome. J Manag Educ 2018;42:199–210. 10.1177/1052562917747013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Valero Sanchez MM. Decisions, practices, and experiences of disclosure by academics with invisible disabilities at German universities. Disabil Soc 2023;1–22:1–22. 10.1080/09687599.2023.2256057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Brown N, Leigh J. Ableism in Academia: Theorising Experiences of Disabilities and Chronic Illnesses in Higher Education [Internet]. In: Brown N, Leigh J (eds). London, England: UCL Press, 2020, 241. https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/51775 (18 January 2024, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- 40. Santuzzi AM, Keating RT. Neurodiversity and the disclosure dilemma. In: Neurodiversity in the Workplace. Routledge, London, 2022. p. 124–48, 10.4324/9781003023616-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Toth KE, Yvon F, Villotti P, et al. Disclosure dilemmas: how people with a mental health condition perceive and manage disclosure at work. Disabil Rehabil 2022;44:7791–801. 10.1080/09638288.2021.1998667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Stergiou-Kita M, Grigorovich A, Damianakis T, et al. The big sell: managing stigma and workplace discrimination following moderate to severe brain injury. Work 2017;57:245–58. 10.3233/WOR-172556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lindsay S, Fuentes K. It is time to address ableism in academia: a systematic review of the experiences and impact of ableism among faculty and staff. Disabilities 2022;2:178–203. 10.3390/disabilities2020014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lindsay S, Osten V, Rezai M, et al. Disclosure and workplace accommodations for people with autism: a systematic review. Disabil Rehabil 2021;43:597–610. 10.1080/09638288.2019.1635658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kerschbaum SL, Eisenman LT, Jones J, Negotiating Disability: Disclosure and Higher Education. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, 2017, p. 385. 10.3998/mpub.9426902. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Couzens D, Poed S, Kataoka M, et al. Support for students with hidden disabilities in universities: a case study. Intl J Disabil Dev Educ 2015;62:24–41. 10.1080/1034912X.2014.984592.. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirmed that the data supporting the findings of the study are available within the article and its supplementary materials.