Abstract

Time-lapse microscopy for embryos is a non-invasive technology used to characterize early embryo development. This study employs time-lapse microscopy and machine learning to elucidate changes in embryonic growth kinetics with maternal aging. We analyzed morphokinetic parameters of embryos from young and aged C57BL6/NJ mice via continuous imaging. Our findings show that aged embryos accelerated through cleavage stages (from 5-cells) to morula compared to younger counterparts, with no significant differences observed in later stages of blastulation. Unsupervised machine learning identified two distinct clusters comprising of embryos from aged or young donors. Moreover, in supervised learning, the extreme gradient boosting algorithm successfully predicted the age-related phenotype with 0.78 accuracy, 0.81 precision, and 0.83 recall following hyperparameter tuning. These results highlight two main scientific insights: maternal aging affects embryonic development pace, and artificial intelligence can differentiate between embryos from aged and young maternal mice by a non-invasive approach. Thus, machine learning can be used to identify morphokinetics phenotypes for further studies. This study has potential for future applications in selecting human embryos for embryo transfer, without or in complement with preimplantation genetic testing.

Keywords: machine learning, morphokinetics, preimplantation mouse embryos, time-lapse microscopy, maternal aging, predictive modeling

Maternal aging in murine in vitro fertilization shows faster cleavage and compaction stages of embryonic development by time-lapse microscopy, and artificial intelligence predicts the aging phenotype.

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

Introduction

Over the past decade, time-lapse microscopy with concurrent embryo culture has emerged as a revolutionary non-invasive technology in the field of human reproduction. This innovation enables continuous embryo culture while capturing multi-planar images every 10–30 min [1, 2]. These images record the stages of preimplantation embryonic development, from fading of the pronuclei to blastulation. The process of tracking the temporal events during embryogenesis is termed embryo morphokinetics.

Morphokinetics has significant applications in human in vitro fertilization (IVF) clinics [1, 2], particularly in selecting viable embryos for implantation, possibly supplementing preimplantation genetic testing and improving pregnancy [3–6]. Changes in embryo morphokinetics are linked to many phenotypes including blastocyst formation [7–10], aneuploidy status [11–18], ovarian disease [19–21], and pregnancy rates [4, 22–34].

Morphokinetics also serves as a critical tool in mouse preimplantation embryo research. The mouse presents as a robust model for in-depth embryological studies due to its extensive genetic and morphokinetics studies [35–40]. However, there is currently a knowledge gap in understanding the detailed molecular events that govern the preimplantation embryo morphologic development [41, 42]. Recent studies show correlations between biomarkers and embryo morphokinetics [43–48]. Further studies in non-invasive embryo morphokinetics would allow researchers to couple invasive molecular tests such as RNA-sequencing for gene signatures with morphokinetic patterns. One method to improve the study of morphokinetics is to add machine learning as in human studies noted above.

Machine learning is particularly useful for analyzing, characterizing, and automating the analysis of large datasets (many embryos) with complex features (multiple time points or images), both of which are present in morphokinetics [49]. There are two types of machine learning, supervised and unsupervised. Supervised learning refers to running different mathematical models that best fit the data to predict an outcome. Here, the investigator labels the predictor variables, such as morphokinetic time points, and uses one or multiple algorithms with different parameter settings to best predict the outcome variable (such as young vs aged). Many mathematical models can be used including regression, classification models [49]. In contrast, unsupervised learning refers to the use of mathematical models to find patterns in the data (such as slow or fast morphokinetics) without any prior knowledge of the type of data (whether embryos came from aged or young mice). Unsupervised algorithms include clustering methods such as principle component analysis [49]. A third type of newer machine learning that requires large computational power is deep learning, or artificial neural networks. Deep learning is useful to analyze very large datasets such as the pixels from embryo time-lapse images [50, 51]. With recent advancements in computational power, numerous studies now employ artificial intelligence (AI) and deep learning technologies [50, 52–54] to analyze still images [55–58] and videos [59] of embryo development.

In this study, we investigated the impacts of maternal aging on preimplantation development using morphokinetics. Studies of embryos from women of advanced reproductive age show significant changes in individual morphokinetics time points [60] that are likely related to poor response to hormonal stimulation [61]. The mouse has been used as a model of ovarian aging as aged maternal mice have decreased oocytes, increased aneuploidy rates, and decreased litter sizes [62–64]. By comparing embryos derived from both young and aged oocytes, we aim to uncover potential morphokinetic phenotypes associated with maternal aging using machine learning.

Materials and methods

Generation of embryos

All animal work was conducted in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee standards and guidelines at Baylor College of Medicine. All necessary ethical standards for conducting research involving animals have been rigorously followed. All mice were housed in a temperature-controlled environment with 12 h light and dark cycles at the B4 barrier level. Both young (3–4 weeks old) and aged (10–14 months old) female C57Bl6/NJ mice underwent ovarian hyperstimulation. Superovulation was induced by intraperitoneal injection of 5 IU pregnant mare serum gonadotropins during random cycle followed by 5 IU of human chorionic gonadotropin 48 h later. Oocytes were harvested 16–18 h later as previously described [65–67]. Briefly, a laparotomy incision was performed followed by oviduct excision under dissection microscopy. An incision was made on the oviduct and cumulus oocyte complexes were harvested in human tubal fluid (HTF) media (Millipore). The oocytes were inseminated by conventional method with fresh sperm from a 4–5 month-old male C57Bl6/NJ donor [65–67]. Briefly, sperm was harvest from the cauda epididymis, incubated in methyl-b-cyclodextrin with modified Krebs–Ringer bicarb solution (THY). Zygotes were washed, sorted, and manually counted in HTF media (Millipore).

Embryo culture

Fertilized zygotes were isolated and cultured in 20 uL of potassium simplex optimization medium (KSOM) (Millipore) in Embryoscope Plus (Vitrolife) incubator under humidified atmosphere at 37 °C with 6% CO2 and 20% atmospheric oxygen. Embryos were observed under time-lapse microscopy until embryonic Day 4.5. Images were obtained every 12 min at 11 focal planes under bright field microscopy. Multiple experimental cohorts were conducted to minimize bias (replicate group 1 n = 80, replicate group 2 n = 133, replicate group 3 n = 143, replicate group 4 n = 47). Details of the number of aged, young, and arrested embryos for each group are shown in Supplementary Figure 1A. Each experimental cohort contained at least five maternal donors. For each experiment, sperm from one 4–5-month donor C57/Bl6/NJ male mouse was used to inseminate all oocytes. Each maternal donor contributed approximately 4–10 oocytes as oocytes were pooled, washed, inseminated, and then counted. Each maternal donor contributed 3–23 embryos (young group) and 4–21 embryos (aged group).

Morphokinetics annotations

Following time-lapse microscopy, embryo images were exported from the EmbryoViewer software (Vitrolife) at the plane with the best focus of the image. Images were manually reviewed until 94.5 h post-insemination. The time at which embryos reached a developmental milestone was recorded. Each embryo received a code that blinded the phenotype from the person performing annotations. The person annotating was trained by an embryologist and IVF lab director at the Texas Children’s Family Fertility Center. Fourteen morphokinetics time points were manually annotated for each embryo from time to fading of pronucleus to time to expanded blastocyst. Time points were defined as follows: tPNf—time to fading of the pronuclei, t2—time to reach 2-cell stage, t3—3-cell, t4—4-cell, t5—5-cell, t6—6-cell, t7—7-cell, t8—8-cell, t9—9-cell, tM—morula (>80% fading of cell membrane/compaction), tSB—development of small pocket of blastocele, tB—development of 50% blastocele, tEB—development of enlarged blastocyst with thinned zona pellucida.

Statistical analysis

A statistical consult was made with the institutional statistics team (Biostatistics and Analytics Group of the Biostatistics and Informatics Shared Resource). Analysis methods were recommended by the statistics team. Analysis was performed by authors. Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare differences among all the time points. Kaplan–Meier survival estimates were used to compare the two experimental cohorts for each time-to-event (time point). Time in hours was a continuous variable. The log-rank test for equality of survivor functions was used to compare differences in time-to-event between the two cohorts. Statistical analysis and visualizations were performed with JMP Pro, Prism, and Stata.

Unsupervised machine learning

Embryos that arrested prior to reaching blastocyst stage were excluded. Data from all experimental cohorts were pooled. The Normal Mixtures model was used for unsupervised clustering due to overlapping distributions and its specificity for numerical data. The means, standard deviations, mixture proportions, and correlations were calculated from the maximum likelihood estimation (expectation–maximization [EM] algorithm) [68]. Number of clusters tested ranged from 2 to 12 using JMP Pro 17. Default parameters used included 30 tours, 300 maximum iterations, and 1e-8 converge criterion.

Supervised machine learning

Embryos that arrested prior to reaching blastocyst stage were excluded from machine learning analysis. Morphokinetic data of embryos that reached the blastocyst stage from all experimental cohorts were uploaded to Jupyter Notebook 6.5.4 through Anaconda Navigator [69]. Predictors were all morphokinetics time points in hours. Outcome variable Age was encoded as a binary variable of 0 = Young and 1 = Aged. Total data were split into 70% training set and 30% test. Predictive models tested were XGBoost (extreme gradient boosting) [70], random forest [71], and logistic regression [72] using scikitlearn [73]. Further hyperparameter tuning was conducted on the test data with five-fold cross validation (splitting data into five sections and training four sections and validating on one section with repeats until all sections are tested). Hyperparameters tuned for logistic regression were: penalty of l1, l2, elasticnet, or none; C of np.logspace −4, 4, and 20; solver of lbfgs, newton-cg, liblinear, sag, and saga, max_iterations. For random forest classifier: n_estimators of 200 and 500, max_features of auto, sqrt, anog2; max_depth of 4 to 8; criterion of gini and entropy. For XGBoost: min_child_weight 1, 5, 10; gamma 0.5 to 5; subsample 0.6 to 1.0; colsample_bytree 0.6 to 1.0, max_depth 3 to 5. Confusion matrices were generated.

Results

Morphokinetic study

We sought to determine the morphokinetic parameters of in vitro embryo growth comparing young versus aged oocyte donors. To do this, we superovulated young (4 week-old) and aged (10–14 month-old) female C57BL6/NJ mice by injecting pregnant mare serum gonadotropins (PMSG) followed by human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) (Figure 1A). Oocytes from both cohorts were harvested from the oviduct and were inseminated with fresh sperm from a 4–5 month-old male C57BL6/NJ mouse. Following insemination, the zygotes were placed under time-lapse microscopy in the Embryoscope Plus incubator for 95 h post-insemination. Images during the time-lapse were reviewed, and each embryonic developmental hour was annotated manually (Figure 1B). Each time point was collected and compared for each embryo between the aged and young cohorts using time-to-event and machine learning methods.

Figure 1.

Schematic of methods. (A) Two cohorts of young (n = 5) and naturally aged (n = 10) female mice underwent ovarian hyperstimulation, oocyte harvest, and in vitro insemination, with time-lapse microscopy. (B) Following incubation of zygotes to the blastocyst stage, still images of each embryo were annotated manually and analyzed using statistical methods in the figure.

Comparisons between young and aged at each time point

The number of mice and embryos per experimental group are listed in a table in Supplementary Figure 1A. There was no difference in the total number of embryos obtained for each group for each experimental cohort. More mice were used in the aged group to compensate for fewer number of oocytes. Fewer oocytes are obtained after superovulation with aged female mice [64] and thus leading to fewer number of embryos. Recently, human embryo studies show that embryos derived from aged mothers were more prone to arrest at four to seven cell stages though the morphokinetics timings did not reach statistical significance difference [74]. To test the effect of maternal aging on murine embryo development, we compared the proportion of embryos that reached each developmental stage. We did not find a difference in the number of embryos that arrested between the two groups (Supplementary Figure 1B). To determine whether there were differences in embryo development between the aged (n = 8–13 mice) and the young (n = 5 mice) cohort of embryos, first, we used two-way ANOVA and found a significant difference between the two cohorts (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

(A) Comparison of overall difference in the median number of hours for each morphokinetic time point between young (n = 15) and aged (n = 65) cohorts of embryos using two-way ANOVA (mixed-effect analysis of time vs age). Error bars represent upper and lower quartiles. (B) Further comparison of individual time points for each embryo using Kaplan–Meier survival estimates in the same experimental group. ns = non-significant, *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001, ****P ≤ 0.0001, 0 = young, and 1 = aged embryos.

To compare each time point in this experiment, we used time-to-event analysis in which, for instance, tPNf (time to pronucleus fade) or t8, was treated as a time-to-event variable. We found that the embryos derived from the aged mothers (n = 65) had significantly faster or shorter time to reach cleavage stages of 5-cells, 6-cells, 7, and 8-cells and compaction also known as morula formation (tM) than the young (n = 15) (Figure 2B for each time point). The comparisons of the mean time points between young and aged embryos are shown in Figure 2B. This experiment was replicated three times (the number of embryos per experiment and time-to-event analysis of each time point for the first experiment are shown in Supplementary File 1). The results demonstrate that the embryos derived from aged maternal donors were faster to reach the cleavage stages of 5- to 8-cells and compaction but were not faster to blastulate.

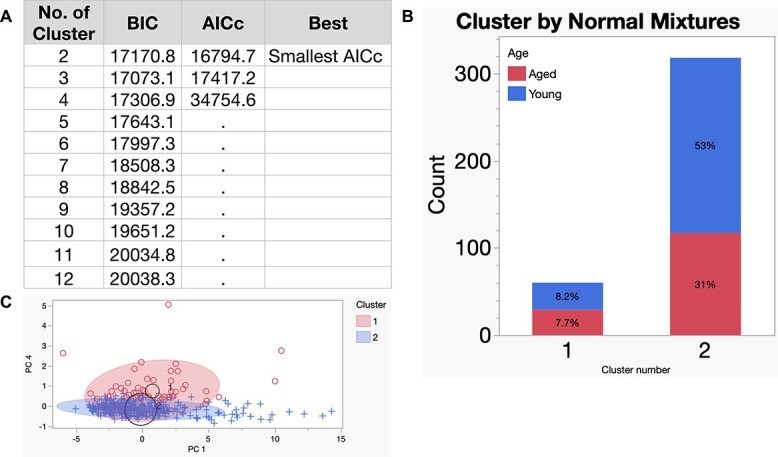

Unsupervised clustering of blastocysts

Next, we asked whether machine learning techniques could distinguish between the two cohort of blastocyst embryos using an unsupervised clustering approach. Missing data for each time point represented embryos that arrested prior to reaching blastocyst stage. These embryos were thus excluded as they likely represented a different biological groups of aged embryos. Here, we used the Normal Mixtures method to cluster the remaining embryos (n = 328) based on the number of hours for each time point without any scientific input beforehand (i.e., the algorithm did not know a priori which embryos were from the aged (n = 146 or young (n = 182) cohorts). To determine the optimal number of clusters, we reran this algorithm with 2, 3, etc., and up to 12 clusters. We compared the performance of each clustering analysis by assessing their Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) and Akaike Information Criterion (AICc) scores (Figure 3A). The number of clusters with the best performance was 2. To determine the distribution of aged and young embryos in each cluster, we graphed the proportions of young and aged embryos in each cluster (Figure 3B). Cluster 2 had higher count and percentage of embryos in the aged cohort (63% vs 37%), while Cluster 1 appeared to have equal representation of aged (48%) and young (52%) embryos (Figure 3B). Spatial visualization of the two clusters by principal components (PC) showed that there was overlap between the two clusters (Figure 3C). Therefore, these data showed that embryo morphokinetic patterns can be clustered into two primary clusters with one predominantly containing young embryos.

Figure 3.

Unsupervised clustering by Normal Mixtures. (A) Comparison of cluster performance by corrected AICc and the BIC. (B) Number of embryos in each cluster by normal mixtures clustering method. Normal mixtures model was used for unsupervised clustering due to overlapping distributions and its specificity for numerical data. Percent of aged or young embryos in each cluster. (C) Visual representation (biplot) of distribution of data for each cluster by PCs 1 and 4. Shaded area represents contour density with 90% confidence interval. Top oval with circular dots represents cluster 1 and thin oval with + signs represents cluster 2. Black circles surround the cluster center and their sizes are proportional to the count for each cluster.

Supervised machine learning

We then asked whether embryo morphokinetics can predict phenotype using non-invasive time lapse microscopy. To do this, we used supervised machine learning algorithms to predict whether the embryo was from the aged or young cohorts. We split the data into 70% training set and 30% test set and trained on three models of logistic regression, random forest, and XGBoost (Figure 4A). The original dataset is shown in Supplementary File 2. Each model gave accuracy of 0.76. Therefore, each model underwent hyperparameter tuning with 5-fold cross validation to prevent overfitting, totaling 2025 model fits. After tuning, the model that performed the best was XGBoost (Figure 4B) with the following hyperparameters:

Figure 4.

(A) Diagram of supervised machine learning strategy and (B) performance of each model before and after hyperparameter tuning on the test set.

colsample_bytree = 0.8, gamma = 2, max_depth = 3, min_child_weight = 1, subsample = 0.8

The XGBoost model performed best of the three with an accuracy of 0.78, precision 0.81, and recall 0.83. Confusion matrices are shown in Supplementary File 1. For the XGBoost algorithm, 20 embryos were misclassified from total of 114 in the test set. Out of the 20, 9 were misclassified as “aged” and 11 were misclassified as “young.” Therefore, machine learning models with hyperparameter tuning can predict the aged phenotype of mouse embryos in this dataset.

Discussion

These findings provide several scientific insights. First, the results demonstrate that embryos from aged mothers had significantly faster cleavage stages and compaction and relatively unchanged blastulation compared to that of the young group. This implies that despite having faster development at cleavage and compaction stages, the embryos from aged mothers had relatively slower blastulation that matched that of the young cohort. Similarly, in human embryo data, maternal age significantly impacts the morphokinetics [60] and is associated with not only faster cleavage stages [75] but also slower blastulation development [76, 77]. In human IVF, slower blastulation is associated with lower pregnancy and higher aneuploidy rates [78]. Faster cleavage is also seen in other diseases such as endometriosis [79], maternal obesity [80], and polycystic ovarian syndrome [19]. Indeed, more studies are needed to understand the impact of aging on preimplantation embryo growth [81, 82].

Interestingly, abnormal cleavage rates such as delayed cleavage of zygotes are associated with abnormal chromosomal segregation, caused by the activation of the spindle assembly checkpoint (SAC) [83]. During cell division, the SAC safeguards against chromosomal errors by halting the cell cycle progression until chromosomes are properly aligned [84]. In aging, the SAC becomes activated likely due to DNA damage accumulated in embryos from aged oocytes. The SAC may explain the change in the morphokinetics found in this study. Further analysis is needed on the level and role of the SAC on embryo development in maternal aging.

This study shows that the embryos from aged maternal donors were slower to complete fading of the pronuclei (tPNf). The breakdown of the pronuclei on microscopy represent integration of the male and female chromosomes. Similarly, in human embryo, delayed fading of the pronuclei is associated with poor oocyte quality [85], maternal aging [77], and decreased embryo viability [86]. Maternal aging is also linked with greater oxidative stress, abnormal gene expression, DNA damage, chromosomal segregation errors, and abnormal stringency of the SAC [87–89]. Thus, we show that aged maternal oocytes induce delayed pronuclear breakdown likely attributable to abnormal oocyte quality.

Notably, there was no difference in the proportion of embryos that underwent developmental arrest in the aged maternal donors, though there was a trend for human embryos that arrest on Days 4–7 in other studies [74]. This could be explained by either a needing a greater number of embryos to detect a difference or that perhaps there are intrinsic differences between the murine and human embryos.

In this study, cleavage stages and morula formation were altered in embryos from aged mothers. Development of the cleavage stages coincides with embryonic genome activation and detection of paternal transcripts in humans [90–92]. The cleavage stages in the human embryo correlate with blastulation, ploidy status, and implantation rate [10, 93, 94]. The activation of the zygotic genome may potentially be altered in the aged embryos.

Interestingly, our study also highlights the alteration of the morula and blastocyst stages in maternal aging. There could be several reasons for this observation. First, delayed blastulation (time from fading of pronuclei to blastocyst stage) occurs in embryos with multi-pronuclei (PN) in bovine models [95] and is associated with abnormal fertilization [96]. Multi-PNs in human zygotes are also associated with high rates of aneuploidy [97, 98]. Multi-PN zygotes were not excluded from this study, and thus, the presence of multi-PN could have explained why the aged embryos had delayed blastulation. For this study, we were unable to determine the number of multi-PN zygotes. The mouse strain used in this study, C57/BL6, is known to have granular cytoplasm and small pronuclei, making it difficult to visualize the total number of pronuclei compared to other strains such as Friend leukemia virus B (FVB) that have clear cytoplasm and large pronuclei [99]. Therefore, a caveat to interpreting the data is that we did not account for the presence of multi-PN and thus, multi-PN could have explained the differences in phenotype. To characterize the effect of aging on the frequency of multi-PN, further studies either with the FVB mouse strain or with a novel pronuclear imaging techniques for the C57 strain would be needed. A second explanation of delayed compaction and blastulation is that these two stages represent many critical development changes. The blastocyst stage coincides with the completion of zygotic genome activation, lineage-associated gene expression heralding lineage commitment [92]. The morula and blastocyst formation also coincide with genome-wide nadir of DNA methylation as a landmark for stem cell pluripotency [100]. The morula stage is also concurrent with embryonic expression of E-cadherin and other adhesion molecules to establish cell-to-cell contact for compaction, required for cellular organization [41, 101]. At this time, two differentiated cell lineages develop within the morula: outer cells that become the trophoblast and inner cells that become the inner cell mass of the blastocyst [102]. Major cell reorganization, changes in symmetry, and suppression of many pluripotency genes such as OCT4 along with upregulation of maternal effect epigenetic regulators such as Kdm4a take place as the morula transforms into a blastocyst [42, 103, 104]. These carefully coordinated events may be dysregulated in aged embryos that progress faster to the morula but slower to the blastocyst stage.

Second, the findings in this study demonstrate that AI algorithms can distinguish between embryos from aged and young maternal donors with as few as about 300 samples. Typically, greater sample sizes are needed for direct analysis of images with deep neural network models. This is because the model will need to be trained to recognize not only cells but also stages of development and how to classify normal from abnormal stages [105]. Here, the information in the images was condensed into morphokinetics continuous variables. Then, these variables can train predictive machine learning models with modern processors with as few as 5–10 donor mice per cohort. Overall, this technique can be used in any laboratory (code provided in the Supplementary material).

In the best-performing XGBoost algorithm, in the test set, 7.9% of embryos from the young cohort were misclassified as aged. Indeed, there may have been embryos in the young cohort with poor morphokinetic performances that caused the algorithm to misclassify them. Even in young, pubertal control mice, a small proportion of embryos never reach the blastocyst stage (10–20%) [106, 107], presumably due to poor-quality oocytes. Thus, additional studies are needed to test whether the misclassified young embryos have poor reproductive potential as that of the aged group into which they were misclassified.

Third, this machine learning technique can be a non-invasive tool to describe embryo morphokinetics phenotypes while still preserving their cellular data. Morphokinetic patterns generated by AI are non-destructive compared to invasive interventions such as trophectoderm biopsy for preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A). Time lapse microscopy allows one to study and classify embryos during development and still allow molecular analysis on the same embryos, if desired. In other words, one can link this phenotype of the embryo to the molecular analysis result to study genotype–phenotype correlations. Examples of murine molecular analysis applications include embryo outgrowth assays and genetic screens, such as the Knockout Mouse Project [108], where morphokinetics can serve as a phenotype for preimplantation embryo screens.

The strengths of the study include the merger of AI with time-lapse microscopy to describe how early embryonic growth is changed due to the effect of maternal aging. We found that maternal aging is associated with accelerated cleavage stage and morula development and relative slowing of blastulation compared with their younger counterparts. This difference can be discerned using AI algorithms so that this aging phenotype may be predicted in future studies. Another strength of the study is the non-invasive approach of time-lapse microscopy. This allows one to gather comprehensive imaging data of each embryo without disturbing the external conditions such as temperature and carbon dioxide concentration. Thus, critical stages such as fading of the pronuclei are captured without physical interference.

A limitation of this study is that embryos were processed as a pooled cohort for each phenotype and thus how individual mice contributed to embryo development cannot be controlled. Further studies are needed to validate the findings. More studies will also be needed to test different mouse strains in different laboratory conditions and in greater numbers. With a larger dataset, other advanced AI techniques can be used such as time-lapse image classification [109]. Another limitation of this study is that arrested embryos were excluded from machine learning analysis due to a low number of embryos and lack of significant differences between the two experimental cohorts. Additional studies with greater numbers of arrested embryos could be incorporated into future studies.

Additionally, a limitation with our unsupervised machine learning is that default parameters were used in order to optimize faster training speed rather than optimized model in the context of high throughput of data. Therefore, additional classification methods should be tested in the future with parameters that optimize the model performance.

In summary, we show that maternal aging is associated with faster cleavage stage embryonic development in mouse and that AI can be used to predict this aging phenotype. These findings demonstrate that maternal aging alters embryo development using AI and morphokinetics and contributes to our understanding of reproductive aging with possible applications in embryo selection in IVF.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank all the members of the Texas Children’s Family Fertility Center and the Division of Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility. We also thank the Baylor College of Medicine Genetically Engineered Rodent Models (GERM) Core and John Seavitt and Jing Liu for technical support. We thank Darius Devlin for his expertise and writing assistance. Graphical abstract was created with BioRender.com.

Footnotes

† Grant Support: This work was supported by the National Human Genome Research Institute/National Institutes of Health (UM1 HG006348 to JDH), by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) (grant 5K12HD047018 to LY), and by the Baylor College of Medicine Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology internal fellowship grant (to LY). The project described was also supported by a Career Development Award from the American Society of Gene & Cell Therapy (to LY). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the American Society of Gene & Cell Therapy. This research was also supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, Clinical Science Research and Development (VA CSRD grant no. IK2 CX001981 to AC) and Health Services Research and Development (#CIN 13-407). The views expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government.

Contributor Information

Liubin Yang, Division of Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas, USA; Division of Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility, Division of Reproductive Sciences, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Sciences, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut, USA; Department of Molecular and Human Genetics, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas, USA.

Carolina Leynes, Department of Molecular and Human Genetics, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas, USA.

Ashley Pawelka, Department of Molecular and Human Genetics, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas, USA.

Isabel Lorenzo, Department of Molecular and Human Genetics, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas, USA.

Andrew Chou, Pain Research, Informatics, Multi-morbidities, and Education (PRIME) Center, VA Connecticut Healthcare System, West Haven, Connecticut, USA; Section of Infectious Diseases, Department of Internal Medicine, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut, USA.

Brendan Lee, Department of Molecular and Human Genetics, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas, USA.

Jason D Heaney, Department of Molecular and Human Genetics, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas, USA.

Author contributions

LY, BL, and JH contributed to the conceptualization. AP, LY, and IL developed the methodology and validation. LY and AC performed formal analysis. LY, CL, AP, and IL performed experiments and data collection. BL and JH provided resources, funding, and supervision. LY drafted the manuscript. All authors provided critical review and approval of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest: The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Data availability

The data underlying this article are available in the article and in its online supplementary material.

References

- 1. Dolinko AV, Farland LV, Kaser DJ, Missmer SA, Racowsky C. National survey on use of time-lapse imaging systems in IVF laboratories. J Assist Reprod Genet 2017; 34:1167–1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Meseguer M, Pellicer A. One for all or all for one? The evolution of embryo morphokinetics. Fertil Steril 2017; 107:571–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jiang VS, Bormann CL. Noninvasive genetic screening: current advances in artificial intelligence for embryo ploidy prediction. Fertil Steril 2023; 120:228–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Storr A, Venetis C, Cooke S, Kilani S, Ledger W. Time-lapse algorithms and morphological selection of day-5 embryos for transfer: a preclinical validation study. Fertil Steril 2018; 109:276–283.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Aparicio-Ruiz B, Basile N, Perez Albala S, Bronet F, Remohi J, Meseguer M. Automatic time-lapse instrument is superior to single-point morphology observation for selecting viable embryos: retrospective study in oocyte donation. Fertil Steril 2016; 106:1379–1385.e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sarkar P, Jindal S, New EP, Sprague RG, Tanner J, Imudia AN. The role of preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy in a good prognosis IVF population across different age groups. Syst Biol Reprod Med 2021; 67:366–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cetinkaya M, Pirkevi C, Yelke H, Colakoglu YK, Atayurt Z, Kahraman S. Relative kinetic expressions defining cleavage synchronicity are better predictors of blastocyst formation and quality than absolute time points. J Assist Reprod Genet 2015; 32:27–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cruz M, Garrido N, Herrero J, Perez-Cano I, Munoz M, Meseguer M. Timing of cell division in human cleavage-stage embryos is linked with blastocyst formation and quality. Reprod Biomed Online 2012; 25:371–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dal Canto M, Coticchio G, Mignini Renzini M, De Ponti E, Novara PV, Brambillasca F, Comi R, Fadini R. Cleavage kinetics analysis of human embryos predicts development to blastocyst and implantation. Reprod Biomed Online 2012; 25:474–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wong CC, Loewke KE, Bossert NL, Behr B, De Jonge CJ, Baer TM, Reijo Pera RA. Non-invasive imaging of human embryos before embryonic genome activation predicts development to the blastocyst stage. Nat Biotechnol 2010; 28:1115–1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Basile N, Nogales Mdel C, Bronet F, Florensa M, Riqueiros M, Rodrigo L, Garcia-Velasco J, Meseguer M. Increasing the probability of selecting chromosomally normal embryos by time-lapse morphokinetics analysis. Fertil Steril 2014; 101:699–704.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Campbell A, Fishel S, Bowman N, Duffy S, Sedler M, Hickman CF. Modelling a risk classification of aneuploidy in human embryos using non-invasive morphokinetics. Reprod Biomed Online 2013; 26:477–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Campbell A, Fishel S, Bowman N, Duffy S, Sedler M, Thornton S. Retrospective analysis of outcomes after IVF using an aneuploidy risk model derived from time-lapse imaging without PGS. Reprod Biomed Online 2013; 27:140–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chawla M, Fakih M, Shunnar A, Bayram A, Hellani A, Perumal V, Divakaran J, Budak E. Morphokinetic analysis of cleavage stage embryos and its relationship to aneuploidy in a retrospective time-lapse imaging study. J Assist Reprod Genet 2015; 32:69–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Del Carmen NM, Bronet F, Basile N, Martinez EM, Linan A, Rodrigo L, Meseguer M. Type of chromosome abnormality affects embryo morphology dynamics. Fertil Steril 2017; 107:229–235.e222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Desai N, Goldberg JM, Austin C, Falcone T. Are cleavage anomalies, multinucleation, or specific cell cycle kinetics observed with time-lapse imaging predictive of embryo developmental capacity or ploidy? Fertil Steril 2018; 109:665–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lee CI, Chen CH, Huang CC, Cheng EH, Chen HH, Ho ST, Lin PY, Lee MS, Lee TH. Embryo morphokinetics is potentially associated with clinical outcomes of single-embryo transfers in preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy cycles. Reprod Biomed Online 2019; 39:569–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Patel DV, Shah PB, Kotdawala AP, Herrero J, Rubio I, Banker MR. Morphokinetic behavior of euploid and aneuploid embryos analyzed by time-lapse in embryoscope. J Hum Reprod Sci 2016; 9:112–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chappell NR, Barsky M, Shah J, Peavey M, Yang L, Sangi-Haghpeykar H, Gibbons W, Blesson CS. Embryos from polycystic ovary syndrome patients with hyperandrogenemia reach morula stage faster than controls. F&S Reports 2020; 1:125–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schachter-Safrai N, Kan-Tor Y, Karavani G, Or Y, Shufaro Y, Har-Vardi I, Buxboim A, Ben-Meir A. Does quantity equal quality?—a morphokinetic assessment of embryos obtained from young women with decreased ovarian response to controlled ovarian stimulation. J Assist Reprod Genet 2021; 38:1115–1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tabibnejad N, Soleimani M, Aflatoonian A. Serum anti-Mullerian hormone and embryo morphokinetics detecting by time-lapse imaging: a comparison between the polycystic ovarian syndrome and tubal factor infertility. Int J Reprod Biomed (Yazd) 2018; 16:483–490. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yang L, Peavey M, Kaskar K, Chappell N, Zhu L, Devlin D, Valdes C, Schutt A, Woodard T, Zarutskie P, Cochran R, Gibbons WE. Development of a dynamic machine learning algorithm to predict clinical pregnancy and live birth rate with embryo morphokinetics. F S Rep 2022; 3:116–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Adolfsson E, Andershed AN. Morphology vs morphokinetics: a retrospective comparison of inter-observer and intra-observer agreement between embryologists on blastocysts with known implantation outcome. JBRA Assist Reprod 2018; 22:228–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Adolfsson E, Porath S, Andershed AN. External validation of a time-lapse model; a retrospective study comparing embryo evaluation using a morphokinetic model to standard morphology with live birth as endpoint. JBRA Assist Reprod 2018; 22:205–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Aguilar J, Rubio I, Munoz E, Pellicer A, Meseguer M. Study of nucleation status in the second cell cycle of human embryo and its impact on implantation rate. Fertil Steril 2016; 106:291–299.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Almagor M, Or Y, Fieldust S, Shoham Z. Irregular cleavage of early preimplantation human embryos: characteristics of patients and pregnancy outcomes. J Assist Reprod Genet 2015; 32:1811–1815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Basile N, Vime P, Florensa M, Aparicio Ruiz B, Garcia Velasco JA, Remohi J, Meseguer M. The use of morphokinetics as a predictor of implantation: a multicentric study to define and validate an algorithm for embryo selection. Hum Reprod 2015; 30:276–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Carrasco B, Arroyo G, Gil Y, Gomez MJ, Rodriguez I, Barri PN, Veiga A, Boada M. Selecting embryos with the highest implantation potential using data mining and decision tree based on classical embryo morphology and morphokinetics. J Assist Reprod Genet 2017; 34:983–990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chamayou S, Patrizio P, Storaci G, Tomaselli V, Alecci C, Ragolia C, Crescenzo C, Guglielmino A. The use of morphokinetic parameters to select all embryos with full capacity to implant. J Assist Reprod Genet 2013; 30:703–710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Meseguer M, Herrero J, Tejera A, Hilligsoe KM, Ramsing NB, Remohi J. The use of morphokinetics as a predictor of embryo implantation. Hum Reprod 2011; 26:2658–2671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Milewski R, Szpila M, Ajduk A. Dynamics of cytoplasm and cleavage divisions correlates with preimplantation embryo development. Reproduction 2018; 155:1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Petersen BM, Boel M, Montag M, Gardner DK. Development of a generally applicable morphokinetic algorithm capable of predicting the implantation potential of embryos transferred on Day 3. Hum Reprod 2016; 31:2231–2244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pribenszky C, Nilselid AM, Montag M. Time-lapse culture with morphokinetic embryo selection improves pregnancy and live birth chances and reduces early pregnancy loss: a meta-analysis. Reprod Biomed Online 2017; 35:511–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sayed S, Reigstad MM, Petersen BM, Schwennicke A, Wegner Hausken J, Storeng R. Time-lapse imaging derived morphokinetic variables reveal association with implantation and live birth following in vitro fertilization: a retrospective study using data from transferred human embryos. PLoS One 2020; 15:e0242377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kim J, Lee J, Choi YJ, Kwon O, Lee TB, Jun JH. Evaluation of morphokinetic characteristics of zona pellucida free mouse pre-implantation embryos using time-lapse monitoring system. Int J Dev Biol 2020; 64:415–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mallol A, Pique L, Santalo J, Ibanez E. Morphokinetics of cloned mouse embryos treated with epigenetic drugs and blastocyst prediction. Reproduction 2016; 151:203–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nguyen Q, Sommer S, Greene B, Wrenzycki C, Wagner U, Ziller V. Effects of opening the incubator on morphokinetics in mouse embryos. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2018; 229:64–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Walters EA, Brown JL, Krisher R, Voelkel S, Swain JE. Impact of a controlled culture temperature gradient on mouse embryo development and morphokinetics. Reprod Biomed Online 2020; 40:494–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Weinerman R, Feng R, Ord TS, Schultz RM, Bartolomei MS, Coutifaris C, Mainigi M. Morphokinetic evaluation of embryo development in a mouse model: functional and molecular correlates. Biol Reprod 2016; 94:84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wolff HS, Fredrickson JR, Walker DL, Morbeck DE. Advances in quality control: mouse embryo morphokinetics are sensitive markers of in vitro stress. Hum Reprod 2013; 28:1776–1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hamamah S, Assou S, Boumela I, Dechaud H. Gene expression changes during human early embryo development: new applications for embryo selection. In: Nagy ZP, Varghese AC, Agarwal A (eds.), Practical Manual of In Vitro Fertilization: Advanced Methods and Novel Devices. New York, NY, Springer New York; 2012: 421–430. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Niakan KK, Han J, Pedersen RA, Simon C, Pera RA. Human pre-implantation embryo development. Development 2012; 139:829–841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Coticchio G, Pennetta F, Rizzo R, Tarozzi N, Nadalini M, Orlando G, Centonze C, Gioacchini G, Borini A. Embryo morphokinetic score is associated with biomarkers of developmental competence and implantation. J Assist Reprod Genet 2021; 38:1737–1743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ho JR, Arrach N, Rhodes-Long K, Salem W, McGinnis LK, Chung K, Bendikson KA, Paulson RJ, Ahmady A. Blastulation timing is associated with differential mitochondrial content in euploid embryos. J Assist Reprod Genet 2018; 35:711–720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kobayashi M, Kobayashi J, Shirasuna K, Iwata H. Abundance of cell-free mitochondrial DNA in spent culture medium associated with morphokinetics and blastocyst collapse of expanded blastocysts. Reprod Med Biol 2020; 19:404–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lee YS, Thouas GA, Gardner DK. Developmental kinetics of cleavage stage mouse embryos are related to their subsequent carbohydrate and amino acid utilization at the blastocyst stage. Hum Reprod 2015; 30:543–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Milazzotto MP, Goissis MD, Chitwood JL, Annes K, Soares CA, Ispada J, Assumpcao ME, Ross PJ. Early cleavages influence the molecular and the metabolic pattern of individually cultured bovine blastocysts. Mol Reprod Dev 2016; 83:324–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Tejera A, Castello D, de Los Santos JM, Pellicer A, Remohi J, Meseguer M. Combination of metabolism measurement and a time-lapse system provides an embryo selection method based on oxygen uptake and chronology of cytokinesis timing. Fertil Steril 2016; 106:119–126.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Greener JG, Kandathil SM, Moffat L, Jones DT. A guide to machine learning for biologists. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2022; 23:40–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Tran D, Cooke S, Illingworth PJ, Gardner DK. Deep learning as a predictive tool for fetal heart pregnancy following time-lapse incubation and blastocyst transfer. Hum Reprod 2019; 34:1011–1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Tran HP, Diem Tuyet HT, Dang Khoa TQ, Lam Thuy LN, Bao PT, Thanh Sang VN. Microscopic video-based grouped embryo segmentation: a deep learning approach. Cureus 2023; 15:e45429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Bori L, Paya E, Alegre L, Viloria TA, Remohi JA, Naranjo V, Meseguer M. Novel and conventional embryo parameters as input data for artificial neural networks: an artificial intelligence model applied for prediction of the implantation potential. Fertil Steril 2020; 114:1232–1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Fernandez EI, Ferreira AS, Cecílio MHM, Chéles DS, de Souza RCM, Nogueira MFG, Rocha JC. Artificial intelligence in the IVF laboratory: overview through the application of different types of algorithms for the classification of reproductive data. J Assist Reprod Genet 2020; 37:2359–2376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Jasensky J, Swain JE. Peering beneath the surface: novel imaging techniques to noninvasively select gametes and embryos for ART. Biol Reprod 2013; 89:105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Huang B, Zheng S, Ma B, Yang Y, Zhang S, Jin L. Using deep learning to predict the outcome of live birth from more than 10,000 embryo data. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022; 22:36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Khosravi P, Kazemi E, Zhan Q, Malmsten JE, Toschi M, Zisimopoulos P, Sigaras A, Lavery S, Cooper LAD, Hickman C, Meseguer M, Rosenwaks Z, et al. Deep learning enables robust assessment and selection of human blastocysts after in vitro fertilization. NPJ Digit Med 2019; 2:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Theilgaard Lassen J, Fly Kragh M, Rimestad J, Nygård Johansen M, Berntsen J. Development and validation of deep learning based embryo selection across multiple days of transfer. Sci Rep 2023; 13:4235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Thirumalaraju P, Kanakasabapathy MK, Bormann CL, Gupta R, Pooniwala R, Kandula H, Souter I, Dimitriadis I, Shafiee H. Evaluation of deep convolutional neural networks in classifying human embryo images based on their morphological quality. Heliyon 2021; 7:e06298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Feyeux M, Reignier A, Mocaer M, Lammers J, Meistermann D, Barrière P, Paul-Gilloteaux P, David L, Fréour T. Development of automated annotation software for human embryo morphokinetics. Hum Reprod 2020; 35:557–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Akhter N, Shahab M. Morphokinetic analysis of human embryo development and its relationship to the female age: a retrospective time-lapse imaging study. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-Grand) 2017; 63:84–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Guner JZ, Monsivais D, Yu H, Stossi F, Johnson HL, Gibbons WE, Matzuk MM, Palmer S. Oral follicle-stimulating hormone receptor agonist affects granulosa cells differently than recombinant human FSH. Fertil Steril 2023; 120:1061–1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Van Kempen TA, Milner TA, Waters EM. Accelerated ovarian failure: a novel, chemically induced animal model of menopause. Brain Res 2011; 1379:176–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Ruth KS, Day FR, Hussain J, Martínez-Marchal A, Aiken CE, Azad A, Thompson DJ, Knoblochova L, Abe H, Tarry-Adkins JL, Gonzalez JM, Fontanillas P, et al. Genetic insights into biological mechanisms governing human ovarian ageing. Nature 2021; 596:393–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Merriman JA, Jennings PC, McLaughlin EA, Jones KT. Effect of aging on superovulation efficiency, aneuploidy rates, and sister chromatid cohesion in mice aged up to 15 Months1. Biol Reprod 2012; 86:49, 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Ali Khan A, Valera Vazquez G, Gustems M, Matteoni R, Song F, Gormanns P, Fessele S, Raess M, Hrabĕ de Angelis M, the IC. INFRAFRONTIER: mouse model resources for modelling human diseases. Mamm Genome 2023; 34:408–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. INFRAFRONTIER Consortium . INFRAFRONTIER—providing mutant mouse resources as research tools for the international scientific community. Nucleic Acids Res 2014; 43:D1171–D1175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Raess M, de Castro AA, Gailus-Durner V, Fessele S, Hrabě de Angelis M, the IC. INFRAFRONTIER: a European resource for studying the functional basis of human disease. Mamm Genome 2016; 27:445–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. McLachlan GJ, Krishnan T. The EM Algorithm and Extensions. New York: Wiley-Interscience; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 69. Kluyver T, Ragan-Kelley B, Perez F, Granger B, Bussonnier M, Frederic J, Kelley K, Hamrick J, Grout J, Corlay S, Ivanov P, Avila D, et al. Jupyter notebooks—a publishing format for reproducible computational workflows. In: Loizides F, Schmidt B, (eds.), Positioning and Power in Academic Publishing: Players, Agents and Agendas. Amsterdam: IOS Press; 2016.

- 70. Chen T, Guestrin C. XGBoost: a scalable tree boosting system. In: Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining. San Francisco, California, USA: Association for Computing Machinery; 2016: 785–794. [Google Scholar]

- 71. Liaw A, Wiener M. Classification and regression by randomForest. R News 2002; 2:18–22. [Google Scholar]

- 72. McCullagh P. Generalized linear models. Eur J Oper Res 1984; 16:285–292. [Google Scholar]

- 73. Pedregosa F, Varoquaux G, Gramfort A, Michel V, Thirion B, Grisel O, Blondel M, Prettenhofer P, Weiss R, Dubourg V, Vanderplas J, Passos A, et al. Scikit-learn: machine learning in python. J Mach Learn Res 2011; 12:2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- 74. Warshaviak M, Kalma Y, Carmon A, Samara N, Dviri M, Azem F, Ben-Yosef D. The effect of advanced maternal age on embryo morphokinetics. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2019; 10:686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Dal Canto M, Bartolacci A, Turchi D, Pignataro D, Lain M, De Ponti E, Brigante C, Mignini Renzini M, Buratini J. Faster fertilization and cleavage kinetics reflect competence to achieve a live birth after intracytoplasmic sperm injection, but this association fades with maternal age. Fertil Steril 2021; 115:665–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Aslih N, Michaeli M, Mashenko D, Ellenbogen A, Lebovitz O, Atzmon Y, Shalom-Paz E. More is not always better-lower estradiol to mature oocyte ratio improved IVF outcomes. Endocr Connect 2021; 10:146–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Ezoe K, Miki T, Akaike H, Shimazaki K, Takahashi T, Tanimura Y, Amagai A, Sawado A, Mogi M, Kaneko S, Ueno S, Coticchio G, et al. Maternal age affects pronuclear and chromatin dynamics, morula compaction and cell polarity, and blastulation of human embryos. Hum Reprod 2023; 38:387–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Tong J, Niu Y, Wan A, Zhang T. Comparison of day 5 blastocyst with day 6 blastocyst: evidence from NGS-based PGT-A results. J Assist Reprod Genet 2022; 39:369–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Freis A, Dietrich JE, Binder M, Holschbach V, Strowitzki T, Germeyer A. Relative morphokinetics assessed by time-lapse imaging are altered in embryos from patients with endometriosis. Reprod Sci 2018; 25:1279–1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Piquette T, Rydze RT, Pan A, Bosler J, Granlund A, Schoyer KD. The effect of maternal body mass index on embryo division timings in women undergoing in vitro fertilization. F S Rep 2022; 3:324–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Wu Z, Qu J, Zhang W, Liu GH. Stress, epigenetics, and aging: unraveling the intricate crosstalk. Mol Cell 2023; 84:34–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Kerepesi C, Gladyshev VN. Intersection clock reveals a rejuvenation event during human embryogenesis. Aging Cell 2023; 22:e13922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Yao T, Suzuki R, Furuta N, Suzuki Y, Kabe K, Tokoro M, Sugawara A, Yajima A, Nagasawa T, Matoba S, Yamagata K, Sugimura S. Live-cell imaging of nuclear–chromosomal dynamics in bovine in vitro fertilised embryos. Sci Rep 2018; 8:7460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Lara-Gonzalez P, Westhorpe Frederick G, Taylor SS. The spindle assembly checkpoint. Curr Biol 2012; 22:R966–R980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Setti A, Braga D, Guilherme P, Iaconelli A Jr, Borges E Jr. High oocyte immaturity rates affect embryo morphokinetics: lessons of time-lapse imaging system. Reprod Biomed Online 2022; 45:652–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Coticchio G, Mignini Renzini M, Novara PV, Lain M, De Ponti E, Turchi D, Fadini R, Dal Canto M. Focused time-lapse analysis reveals novel aspects of human fertilization and suggests new parameters of embryo viability. Hum Reprod 2018; 33:23–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Park SU, Walsh L, Berkowitz KM. Mechanisms of ovarian aging. Reproduction 2021; 162:R19–r33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Wang X, Wang L, Xiang W. Mechanisms of ovarian aging in women: a review. J Ovarian Res 2023; 16:67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Wang S, Zheng Y, Li J, Yu Y, Zhang W, Song M, Liu Z, Min Z, Hu H, Jing Y, He X, Sun L, et al. Single-cell transcriptomic atlas of primate ovarian aging. Cell 2020; 180:585–600.e19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Tesarík J, Kopecný V, Plachot M, Mandelbaum J. High-resolution autoradiographic localization of DNA-containing sites and RNA synthesis in developing nucleoli of human preimplantation embryos: a new concept of embryonic nucleologenesis. Development 1987; 101:777–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Braude P, Bolton V, Moore S. Human gene expression first occurs between the four- and eight-cell stages of preimplantation development. Nature 1988; 332:459–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Petropoulos S, Edsgard D, Reinius B, Deng Q, Panula SP, Codeluppi S, Reyes AP, Linnarsson S, Sandberg R, Lanner F. Single-cell RNA-seq reveals lineage and X chromosome dynamics in human preimplantation embryos. Cell 2016; 167:285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Vera-Rodriguez M, Chavez SL, Rubio C, Reijo Pera RA, Simon C. Prediction model for aneuploidy in early human embryo development revealed by single-cell analysis. Nat Commun 2015; 6:7601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Chavez SL, Loewke KE, Han J, Moussavi F, Colls P, Munne S, Behr B, Reijo Pera RA. Dynamic blastomere behaviour reflects human embryo ploidy by the four-cell stage. Nat Commun 2012; 3:1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Suzuki R, Okada M, Nagai H, Kobayashi J, Sugimura S. Morphokinetic analysis of pronuclei using time-lapse cinematography in bovine zygotes. Theriogenology 2021; 166:55–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Suzuki R, Yao T, Okada M, Nagai H, Khurchabilig A, Kobayashi J, Yamagata K, Sugimura S. Direct cleavage during the first mitosis is a sign of abnormal fertilization in cattle. Theriogenology 2023; 200:96–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Takahashi H, Hirata R, Otsuki J, Habara T, Hayashi N. Are tri-pronuclear embryos that show two normal-sized pronuclei and additional smaller pronuclei useful for embryo transfer? Reprod Med Biol 2022; 21:e12462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Mutia K, Wiweko B, Iffanolida PA, Febri RR, Muna N, Riayati O, Jasirwan SO, Yuningsih T, Mansyur E, Hestiantoro A. The frequency of chromosomal euploidy among 3PN embryos. J Reprod Infertil 2019; 20:127–131. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Larson MA. Pronuclear microinjection of one-cell embryos. In: Larson MA (ed.), Transgenic Mouse: Methods and Protocols. New York, NY: Springer US; 2020: 27–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Wu J, Izpisua Belmonte JC. Stem cells: a renaissance in human biology research. Cell 2016; 165:1572–1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Piliszek A, Grabarek JB, Frankenberg SR, Plusa B. Cell fate in animal and human blastocysts and the determination of viability. Mol Hum Reprod 2016; 22:681–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Huppertz B, Herrler A. Regulation of proliferation and apoptosis during development of the preimplantation embryo and the placenta. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today 2005; 75:249–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Gamage TK, Chamley LW, James JL. Stem cell insights into human trophoblast lineage differentiation. Hum Reprod Update 2016; 23:77–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Sankar A, Kooistra SM, Gonzalez JM, Ohlsson C, Poutanen M, Helin K. Maternal expression of the JMJD2A/KDM4A histone demethylase is critical for pre-implantation development. Development 2017; 144:3264–3277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Balki I, Amirabadi A, Levman J, Martel AL, Emersic Z, Meden B, Garcia-Pedrero A, Ramirez SC, Kong D, Moody AR, Tyrrell PN. Sample-size determination methodologies for machine learning in medical imaging research: a systematic review. Can Assoc Radiol J 2019; 70:344–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Thouas GA, Trounson AO, Jones GM. Effect of female age on mouse oocyte developmental competence following mitochondrial injury1. Biol Reprod 2005; 73:366–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Melin J, Lee A, Foygel K, Leong DE, Quake SR, Yao MW. In vitro embryo culture in defined, sub-microliter volumes. Dev Dyn 2009; 238:950–955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Cacheiro P, Westerberg CH, Mager J, Dickinson ME, Nutter LMJ, Muñoz-Fuentes V, Hsu CW, Van den Veyver IB, Flenniken AM, McKerlie C, Murray SA, Teboul L, et al. Mendelian gene identification through mouse embryo viability screening. Genome Med 2022; 14:119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Rahman MSS, Ozcan A. Time-lapse image classification using a diffractive neural network. Adv Intell Syst 2023; 5:2200387. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article are available in the article and in its online supplementary material.