Abstract

Background

Injuries are among the leading causes for hospitalizations and emergency department (ED) visits. COVID-19 restrictions ensured safety to Canadians, but also negatively impacted health outcomes, including increasing rates of certain injuries. These differences in trends have been reported internationally however the evidence is scattered and needs to be better understood to identify opportunities for public education and to prepare for future outbreaks.

Objective

A scoping review was conducted to synthesize evidence regarding the impact of COVID-19 restrictions on unintentional injuries in Canada, compared to other countries.

Methods

Studies investigating unintentional injuries among all ages during COVID-19 from any country, published in English between December 2019 and July 2021, were included. Intentional injuries and/or previous pandemics were excluded. Four databases were searched (MEDLINE, Embase, Web of Science, SPORTDiscus), and a gray literature search was also conducted.

Results

The search yielded 3,041 results, and 189 articles were selected for extraction. A total of 41 reports were included from the gray literature search. Final studies included research from: Europe (n = 85); North America (n = 44); Asia (n = 32); Oceania (n = 12); Africa (n = 8); South America (n = 4); and multi-country (n = 4). Most studies reported higher occurrence of injuries/trauma among males, and the average age across studies was 46 years. The following mechanisms of injury were reported on most frequently: motor vehicle collisions (MVCs; n = 134), falls (n = 104), sports/recreation (n = 65), non-motorized vehicle (n = 31), and occupational (n = 24). Injuries occurring at home (e.g., gardening, home improvement projects) increased, and injuries occurring at schools, workplaces, and public spaces decreased. Overall, decreases were observed in occupational injuries and those resulting from sport/recreation, pedestrian-related, and crush/trap incidents. Decreases were also seen in MVCs and burns, however the severity of injury from these causes increased during the pandemic period. Increases were observed in poisonings, non-motorized vehicle collisions, lacerations, drownings, trampoline injuries; and, foreign body ingestions.

Implications

Findings from this review can inform interventions and policies to identify gaps in public education, promote safety within the home, and decrease the negative impact of future stay-at-home measures on unintentional injury among Canadians and populations worldwide.

Keywords: pandemic (COVID19), public health measure, accident, lockdown, restriction

Background

On March 11, 2020, the rapid spread of coronavirus SARS-CoV-2–a highly contagious virus causing flu-like symptoms and potentially hospitalizations and death–resulted in the declaration of the COVID-19 pandemic by the World Health Organization (1). This was followed by countries worldwide rapidly administering public health policies to limit and reduce the spread of the virus, including stay-at-home and physical distancing measures. In Canada, provinces began implementing COVID-19 policies in early March 2020: workplaces shifted to work-at-home arrangements, schools employed virtual learning, and restaurants, recreational spaces, and other “non-essential” businesses closed their doors (2). Despite restrictions to keep populations safe from the virus, injuries continued to occur during this time, including those related to falls, transportation, physical activity, drowning, suffocation, poisoning, burns, violence, self-harm, and suicide (3).

Injuries are one of the leading causes of visits to doctors’ offices, emergency departments, and hospital admissions for all age groups, the most common cause of death in Canadians aged 1–34 years, and the sixth leading cause of death among all ages combined (3–5). Unintentional injuries account for the majority of injury cases, causing 75% of deaths, 89% of hospitalizations, 95% of emergency department visits, and 90% of disabilities (6). Additionally, falls and poisonings were the two leading causes of injury deaths in Canada in 2015 (5). Injuries are predictable and preventable; however, policies enforcing stay-at-home measures, distanced activities, and the disruption of daily routines, had an unknown impact on unintentional injuries.

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, researchers suggested the development of specific critical care service and ethical considerations during pandemics and disasters (7, 8). They noted that during pandemics or disasters, health care facilities may experience a surge in patients, and vulnerable populations may be further marginalized due to the challenges in accessing health care services (7, 8). To address these issues, Hick and colleagues (8) created recommendations through a modified Delphi process for those involved in large-scale disaster and pandemic responses, particularly with respect to critically ill or injured patients. Their recommendations included capacity and capability planning for mass critical care, increasing awareness and information sharing, reducing the burden on critical care facilities, planning for the care of vulnerable populations, and the reallocation of healthcare resources (8). The recommendations were then categorized to those that were most relevant to each of their target audiences (i.e., clinicals, hospital administrators, and public health/government). Using a similar approach to explore and understand the most common mechanisms of injury during disaster, pandemic, and lockdown periods will allow researchers, healthcare providers, and public health and government officials to better identify gaps in healthcare response and capacity. In addition, recognizing the most common mechanisms of injury and high-risk settings during disasters or pandemics will allow for the development of focused public education and awareness campaigns, facilitating the reduction of injury incidence during and outside of lockdown periods.

The COVID-19 pandemic affected populations at a global level, and its impact on hospitalizations and emergency department visits varied at provincial and national levels from country to country. The primary reason for this variation could potentially be due to the dissimilarities in how and when the public health measures were implemented. A large body of evidence has been published by different countries across the globe comparing the trends and patterns of unintentional injuries during COVID-19 versus pre-pandemic. From a public health and policy perspective, it is essential to synthesize and understand the similarities and differences in the trends of these unintentional and potentially preventable injuries, so that injury burden and the utilization of health care services and resources may be reduced during future similar circumstances.

The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the importance of reliable and comprehensive data that would allow for informed decision-making. The Public Health Agency of Canada is responsible for the national surveillance of intentional and unintentional injury and poisoning (9). Unfortunately, routine data collection for many national data sources was impacted by the pandemic and data collection reduced/ceased. Thus, this review also aimed to identify how other health data continued to be collected during the pandemic, and how similar methods might be implemented and utilized to assess injury patterns in Canadian systems in future events. The objective of this review was to – (a) explore and summarize evidence supporting the effects of public health measures related to COVID-19 on the trends and patterns of unintentional injuries in Canada; (b) to compare the trends and patterns of unintentional injuries in Canada with those observed in other similar countries.

Method

This scoping review was conducted according to the methodological framework designed by Arksey and O’Malley (10), and consisted of five stages: (1) identifying the research question; (2) identifying relevant studies; (3) study selection; (4) charting the data; and (5) collating, summarizing, and reporting the results. The research team included experts in injury epidemiology, evidence synthesis, disability, injury rehabilitation and knowledge translation. Through a series of iterations, the research team agreed upon the scope of the review, inclusion criteria and extraction variables.

In consultation with an academic librarian, Ovid MEDLINE, Embase, Web of Science Core Collection, and SPORTDiscus were searched for scholarly articles for the period December 2019 to July 2021, inclusive. The search strategy consisted of injury-related terms, including wounds and injuries, burns, drowning, electric injuries, occupational injuries, fractures, etc. A Google search for gray literature was also conducted, in which the first 50 results for each mechanism of injury were extracted and screened. The full search strategy is documented in Appendix A (11).

Research questions

The research questions that guided this scoping review, and ensured that a wide range of literature was captured were: (a) What were the effects of the public health measures related to COVID-19 on trends and patterns of unintentional injuries in Canada? (b) How are these trends and patterns comparable to other similar countries?

Identifying relevant studies

To ensure the comprehensiveness of this scoping review, we searched four electronic databases – (MEDLINE, Embase, Web of Science, SPORTDiscus). We also included gray literature, including theses/dissertations and reports revealed by Google. Studies were included if they were published in English, within the indicated time frame and addressed unintentional injuries among all age-groups and all countries, worldwide. For the purposes of this review, unintentional injuries were defined as any injury that is not caused on purpose or with intention to harm (11). Studies were excluded if they focused on intentional injuries and/or previous pandemics. Only primary research was included in the final article selection (i.e., no reviews, letters to the editor, etc.). With respect to gray literature searches, records were selected for inclusion if they were published by news outlets, blogs, non-profit organizations, academic institutions, government, or public health websites.

Study selection

The identification of the search strategy followed an iterative process. First, we conducted a preliminary search in Medline and explored article titles, abstracts, keywords and subject headings to develop our search strategy. We then included the identified keywords and subject headings in the search strategy of all four databases, constituting the final search strategy. A faculty librarian provided expert guidance and verification regarding the appropriate subject headings, and adaptation of search strategies across databases. Search results were imported into Covidence (12) and duplicates were automatically removed by the software. To ensure accuracy in screening and capturing relevant studies using the search criteria in Covidence, three reviewers (SK, SS, OR) screened a random sample of 50 articles. During the first round of screening (title and abstracts), the reviewers erred on inclusion and an iterative process involving meetings among the reviewers to refine search criteria was used. Title and abstracts followed by full-text review were completed independently by two reviewers (SK, SS or OR) using Covidence. For disagreements among the reviewers, data from the article was discussed to achieve consensus. If consensus could not be reached, a third reviewer was consulted and served as arbiter to reach consensus.

Charting the data

Once the final studies were selected, data extraction was conducted using Microsoft Excel. Data was extracted based on the following categories: fell within the date range for data collection, study design, data sources, sample size, demographics, and injury descriptors. The injury categories could not be mutually exclusive as their classification varied across regions. The categories included the external causes of injuries (falls, non-motorized vehicle collisions, trampoline, motor vehicle collisions, sports/recreation; pedestrian vs. motor vehicle, burns, work-related, crush/trapped, lacerations, foreign body ingestion, poisoning, drowning), and injury settings (e.g., at home, at work, etc.).

Results

Search results

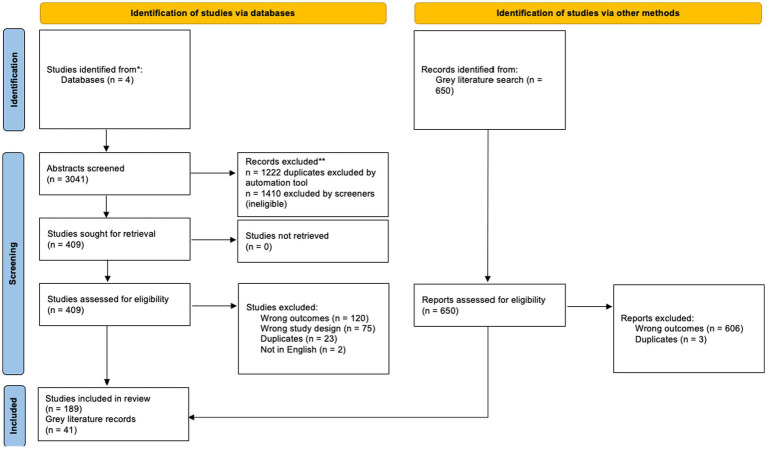

Of the 3,041 references uploaded to Covidence, 1,222 were duplicates, 1,819 were screened for title and abstract relevance, and 409 were advanced to full-text review. A total of n = 189 peer-reviewed articles were included in final analysis. An additional n = 41 gray literature records were also included. See Figure 1. PRISMA table outlining study selection process.

Figure 1.

PRISMA table of articles selected for study.

Study characteristics

Most studies compared pandemic period trends in their respective countries to the same dates during pre-pandemic time periods to explore differences in injury presentations/cases. The pandemic time periods varied depending on the region, and the pre-pandemic periods included between one and 5 years prior to COVID-19 lockdowns. For an overview of study characteristics, including region, study design, and mechanism of injuries see Table 1.

Table 1.

Overview of study characteristics.

| Region | n, % |

|---|---|

| Europe | 85, 45.0% |

| North America | 44, 23.3% |

| Asia | 32, 16.9% |

| Oceania | 12, 6.3% |

| Africa | 8, 4.2% |

| South America | 4, 2.1% |

| Multi-country | 4, 2.1% |

| Study design | |

| Retrospective review of databases | 128, 67.4% |

| Cohort | 23, 12.1% |

| Other (Time-series, comparative retrospective, secondary analysis, prospective review, quasi-experimental) | 18, 9.5% |

| Cross-sectional | 16, 8.4% |

| Case control | 5, 2.6% |

| Injury categories | |

| Motor vehicle collision/motorcycle collision | 134, 71.0% |

| Falls | 104, 55.0% |

| Sports/recreation | 65, 34.4% |

| Non-motorized vehicle | 31, 16.4% |

| Occupational injury | 24, 12.7% |

| Unintentional injury** | 21, 11.1% |

| Pedestrian injuries | 20, 10.6% |

| Laceration (including bites) | 18, 9.5% |

| Burns | 17; 9.0% |

| Poisoning | 10; 5.3% |

| Crush/trapped | 6; 3.2% |

| Trampoline | 6; 3.2% |

| Foreign body ingestion | 2, 1.1% |

| Drowning | 1* |

*Negligible percentage. **No injury type specified.

Notably, only three studies that met inclusion criteria were based in Canada at the time of the search, and another study was conducted in both the United States and Canada. A total of 144 (76%) of the included articles presented findings on injuries occurring in all age groups, whereas 22 (11.6%) reported on pediatric cases only, 25 (13%) on adult, and one on older adults. In addition, many articles reported on more than one mechanism of injury. A total of 111 (59%) studies indicated that injury incidence was higher among males than females, and the average age across all studies was 45.7 years old (Range or SD?). Various data sources were employed to collect data for each of the studies, with the most frequently used being electronic medical records (n = 47; 25%) and various registries (n = 34; 18%). Some studies consulted more than one data source. For a detailed list of data sources, see Table 2. Studies conducted in Canada used hospital-based and government-based databases.

Table 2.

Data sources used to assess and review injuries of interest.

| Data source | n, % |

|---|---|

| Electronic medical records | 47, 24.9% |

| Patient files, logs, presentations, in-patient and outpatient data, chart reviews, clinical/triage/call notes and reports, discharge summaries, anesthetic charts | 42, 22.2% |

| Registries (i.e., trauma, emergency department, health record, clinical data, burn) | 34, 18.0% |

| Patient admissions | 32, 16.9% |

| Database review (i.e., hospitals, daily death certificates, trauma admissions, emergency department, patient, poisonings, referrals) | 26, 13.8% |

| Governmental, police, or non-profit organization | 14, 7.4% |

| Procedure room/theater/surgery lists | 10, 5.3% |

| Imaging (e.g., CT, radiographs) | 9, 4.2% |

| Google trends/Map Quest/Microsoft Bing services | 5, 2.6% |

| Online survey | 4, 2.1% |

| Publicly available data | 3, 1.6% |

| Other: trauma activations, ambulance activations, phone counseling sessions, prehospital records, consult data, trauma handover list, autopsies, triage register, helicopter emergency requests | 11, 5.8% |

| Media reports | 1* |

*Negligible percentage.

For an overview of gray literature included in this review, see Table 3.

Table 3.

Gray literature results.

| Injury categories | n, % | Type of source(s) | Region(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poisoning | 15, 36.6% | News, organization, academic, government | United States, United Kingdom (United Kingdom), Canada, India, France |

| Motor vehicle collisions | 11, 26.8% | News, organization, public health, government, non-profit | United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, India, Switzerland, New Zealand |

| Drowning | 5, 12.2% | News, academic, government, non-profit | United States, Canada, New Zealand |

| Trampoline | 4, 10.0% | News, government, non-profit | United States, Canada, United Kingdom |

| Unintentional injury | 3, 7.3% | Organization, academic, public health | United States of America (United States), Australia |

| Cycling | 1, 2.4% | Non-profit | United States |

| Orthopedic | 1, 2.4% | Academic | United States |

| Falls | 1, 2.4% | Blog | United States |

| Burns/fire safety | 2, 5.0% | News | Canada |

Place of injury

Forty-eight (13–60) studies reported the place where incidents (e.g., injuries, poisonings) occurred, with most (n = 32; 66%) indicating an increase in incidents within domestic settings (13, 14, 17, 19–21, 23–25, 28, 29, 32–35, 37, 38, 40, 41, 43, 44, 46–49, 51–53, 56–59), 18 of which reported significant increases occurring at home. Domestic injuries were reportedly a result of do-it-yourself and home improvement projects (e.g., use of power tools, ladders, etc.), gardening, scalds, intoxications, exposures to household/cleaning products, and kitchen-related tasks. Only one study reported a decrease in domestic injuries during 2020 compared to the same periods in 2017–2019 (16). One study based in Ireland reported an increase in domestic injuries during the initial two-week lockdown period, followed by a decrease in the number of domestic injuries over the following 2 months (26). Five studies noted a decrease in injuries occurring outdoors and at school/daycare (36, 45, 58–60), four of which were significant decreases. Two studies based in the United Kingdom indicated that during the lockdown period, the majority of injuries occurred in the home or garden (31, 39). Interestingly, two studies reported an increase in injuries occurring outdoors or in public spaces during the lockdown (15, 24). Lastly, six studies reported no significant change in domestic injuries during the COVID-19 period (22, 27, 42, 50, 54, 55). The gray literature (n = 1) also indicated that there was an increase in emergency department visits for unintentional injuries occurring within the home (resulting from do-it-yourself projects).

Unintentional injuries

Thirteen articles reported decreases in unintentional injuries (61–73), with four observing a significant decline during the pandemic period (65, 70, 72, 73). A total of five articles noted an increase in unintentional injuries overall (74–78) when comparing the lockdown period to the same time period in previous years, though none were significant. One research team in South Korea noted they observed a significant decrease in unintentional injuries resulting in facial trauma, but increases in hand trauma when compared to the same period in 2019 (59). Lastly, two studies indicated no differences in unintentional injuries during the pandemic period compared to pre-pandemic periods (79, 80). Gray literature (n = 3) reported increases in death rates as a result of unintentional injury (81–83). See Table 4 for an overview of injury results from both scientific evidence and gray literature.

Table 4.

Injury results during COVID-19 from scientific evidence and gray literature.

| Scientific evidence | Gray literature | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Injury category | Canada | Other countries | |

| Drowning |

n = 1 (84) - Canada and United States based study - Beach drownings in the Great Lakes region significantly higher in 2020 than pre-COVID - Statistically significant increase in drownings for young males (< 20 years) during 2020 than pre-COVID |

n = 5 (85–89) - Reports of increased drownings in open-water and an increase in pediatric drownings - Water Safety New Zealand report found that no fatal drownings had occurred during the first 4 weeks of the lockdown period. |

|

| Poisoning |

n = 2 (65, 90)

|

n = 8 (20, 33, 37, 77, 80, 91–93)

|

n = 15 (94–107)

|

| Foreign body ingestion |

n = 2 (32, 57)

|

||

| Trampoline |

n = 6 (16, 26, 45, 108–110)

|

n = 4 (111–114)

|

|

| Lacerations |

n = 18 (27)

|

||

| Crush/Trap |

n = 6 (27, 42, 76, 115–117)

|

||

| Occupational |

n = 25 (13, 23, 25, 29, 30, 35, 36, 41, 46, 50, 52–54, 58, 62, 118–127)

|

||

| Burns |

n = 1 (65)

|

n = 16 (19, 26, 29, 32, 57, 59, 76, 91, 128–135)

|

n = 2 (136, 137)

|

| Sports and recreation |

n = 65 (13, 14, 16, 21, 23–25, 27, 29, 30, 34–36, 38–41, 43, 45, 48, 50–52, 54, 58, 59, 62, 63, 65, 70, 75, 108–110, 115, 118–121, 123–126, 133, 138–158)

|

||

| Pedestrian |

n = 20 (18, 19, 29, 50, 54, 66, 67, 71, 74, 116, 133, 140, 159–166)

|

||

| Non-Motorized Vehicles (i.e., cycling, two-wheelers, rollerblades, skateboards, and hoverboards) |

n = 31 (16–19, 26, 29, 31, 34, 35, 39, 49, 50, 54, 65, 70, 108, 110, 116, 123, 133, 139, 153, 159, 162, 163, 167–172)

|

n = 1 (173)

|

|

| Falls |

n = 105 (14, 15, 18, 19, 21, 24, 27, 29–31, 34, 38–40, 42, 44, 47, 49–55, 57–59, 62, 63, 66, 69, 70, 74, 75, 79, 91, 108–110, 115, 117, 119–122, 124–128, 133, 139–142, 144, 146, 148, 151, 153–159, 161–163, 165, 168, 170, 171, 174–204)

|

n = 1 (205)

|

|

| Motor Vehicle Collisions (i.e., vehicles and motorcycles) |

n = 134 (13–19, 23, 24, 27–29, 34, 35, 38, 41–45, 47–50, 53–56, 59, 60, 62–71, 74–76, 78, 79, 108–110, 117, 118, 121–128, 133, 139–142, 144–148, 151–154, 156–166, 168, 170, 171, 174, 176, 178–183, 185–194, 196–199, 201, 204, 206–229)

|

n = 9 (230–240)

|

|

Discussion

This scoping review highlights the early impacts of public health measures implemented to reduce the spread of COVID-19 on the trends and patterns of unintentional injuries in Canada, and globally. With the rapid spread of the virus and declaration of a pandemic, populations were confined to their homes, and sports, school, recreation, certain jobs, and non-essential travel were interrupted, resulting in changes in injury patterns. Studies included in this review were predominantly based in Europe, the United States, and Asia, and typically employed a retrospective review of electronic medical records, registries, and databases. Owing to very few (n = 3) studies conducted in Canada at the time of this review, a comparison of data sources between Canadian and international studies could not be done. However, it is of interest to note which types of health data sources were most commonly used during the pandemic.

Studies reported that injuries occurred more frequently among males than females, and the average age across studies was approximately 46 years old. This aligns with current research that states that males are more likely than females to sustain and/or die from injuries (241). Interestingly, this review showed similarities in general trends globally during lockdown periods when compared to previous time points. The impact of the public health measures related to COVID-19 in Canada showed an increase in: (a) domestic injuries (e.g., resulting from do-it-yourself projects or gardening); (b) poisonings resulting from cleaners, disinfectants, and other products; (c) non-motorized vehicle injuries; (d) lacerations (e.g., from sharp objects and bites); (e) drownings; (f) trampoline injuries; and, (g) foreign body ingestions. Decreases were reported in injuries resulting from MVCs, occupation, sport and recreation, pedestrian-related collisions, and crush/trap injuries. The impact of Canadian COVID-19 public health measured showed mixed results for a small number of other mechanisms of injury, for instance, burns and falls showed almost equal numbers of studies reporting increases and decreases. In this review, gray literature sources reported on eight different types of injuries, all reporting an increase in incidence. While the increase in the occurrence or severity of injuries were consistent with the scientific evidence for six injuries (i.e., injuries at home, drowning, trampoline-related injuries, poisonings, non- motorized vehicle injuries, and MVCs), the findings on the other two mechanisms of injury were inconsistent (i.e., falls, burns). This is interesting to note in that sources that were more easily accessible to the public reported inconsistent findings compared to peer-reviewed articles with supporting evidence. This can lead to misconceptions among the public and a lack of understanding of the true burden of injury during disaster or pandemic situations.

An additional shared impact of COVID-19 public health restrictions in many countries was an initial drop in trauma admissions and hospital and health center presentations at the outset of the pandemic (63, 128, 179). When delving deeper into the decreases in injury reported across the various mechanisms of injury, it is first important to note that public health measures implemented to reduce the spread of a previously unknown virus caused fear of contagion among populations, which may have impeded individuals’ willingness to attend healthcare facilities for treatment of any kind (74). Additionally, the avoidance of healthcare facilities, as well as mandates from governments to stay at home, likely also resulted in an underreporting of injuries that occurred during COVID-19 lockdown periods.

General decreases in sport, recreation, crush/trap, and pedestrian injuries were not surprising given the cessation of organized sport and recreational activities, reduction in road traffic, and the rise in working from home. The reduction in occupational injuries was also expected; however, this was context dependent, in that one study reported on an increase in occupational injuries resulting from farm work. This highlights that essential industries were more vulnerable to a continuing risk of injury during the lockdown.

Falls and MVCs were reported as the most common mechanisms of injury during the pandemic, regardless of whether they increased or decreased. This trend remained consistent in that, in Canada, the leading causes for injuries and injury deaths are falls and transport incidents (6). Increased time within domestic settings may have led to a higher incidence of falls requiring medical attention. One research team suggested that promoting social connectedness via remote activities, rather than in person, may be a longitudinal practice that can reduce the incidence of vehicle collisions and injuries (227). They also noted that another factor that may have contributed to the reduction in MVCs was the reduction of alcohol-impaired driving, and therefore emphasis could be placed on engaging in alcohol-related activities with peers within the home and virtually, rather than in-person (227). The creation of other solutions to reduce the incidence of vehicle collisions and injuries, such as the development of more robust public transport system has also been suggested (227). Although, the frequency of MVCs was reported to decrease during COVID-19 lockdowns, an increase in the severity of injuries related to MVCs was reported by many countries. The increase in severity of MVCs was of interest, suggesting that individuals who were driving during COVID-19 lockdowns were more likely to engage in risk-taking behavior (e.g., speeding, racing) causing severe or fatal MVCs compared to before the lockdown (211).

The incidence of burns that occurred during the pandemic showed a similar trend to MVCs - while burns decreased, the incidence of more severe burns increased. In particular, one study team observed increased severity of burns among children (131). This may have been due to children spending more time at home, in conjunction with parents working from home and thus managing multiple responsibilities, which may have impacted their ability to consistently supervise children. Burns due to scalds were reported frequently during the pandemic, suggesting that children may have been reaching for hot surfaces or liquids that were unattended. Further, increased exposure to animals (also possibly unsupervised) during the lockdown may partly explain the surge in animal bites reported.

Only one study investigated the incidence of drownings during the COVID-19 pandemic, reporting a significant increase during the lockdown period (84). The authors suggested that the increase in beach visits may have been driven by the closing of public pools, and the closure of facilities providing swimming lessons. In addition, they note the presence of large crowds at beaches may have confirmed pre-existing biases that the beaches and conditions were safe, despite safety signage or the absence of a lifeguard (84). Further, the researchers explain that these biases are most often observed among young males, who are more susceptible to group think and pleasure seeking at the sacrifice of safety (84). Their results showed that there was a statistically significant increase in the number of young males (< 20 years old) who drowned in the Great Lakes during the pandemic (84).

The increase in reported poisonings is critical to analyze in that many countries experienced a high volume of calls or presentations related to ingestions of household cleaners, disinfectants, hand sanitizer, glue, batteries, and other household products. Researchers note that the increased time at home resulted in more frequent exposures to these products, especially for children, and that limited availability of certain cleaning products during the outset of the pandemic may have led to inappropriate mixing of other products, resulting in adverse outcomes (65, 90, 92). These findings suggest that efforts should be focused on increasing public awareness regarding ingestion or inhalation of household products, as well as checking that the products they are using have been approved by their country’s health authority (93). Further, children using hand sanitizers should be supervised and all products should be kept out of their reach, which is of particular concern when they are confined to the home environment (93), and the use of hand sanitizer was highly encouraged as part of the pandemic public messaging.

From this review, it is evident that public health policies can have a significant impact on mechanisms of unintentional injury and therefore targeted efforts should be made toward prevention and injury surveillance, particularly during lockdown or physical distancing periods. For example, an increase in injuries related to trampoline and non-motorized vehicles highlights the importance of targeted efforts to enhance public knowledge and behaviors related to informal sport activities. Further, examining the burden of unintentional injury and most common mechanisms of injury during lockdown periods allows healthcare professionals, researchers, and policymakers to understand gaps in healthcare services and responses with respect to preventing and treating these injuries. Thus, this review also aimed to identify how health data sources continued to be collected during the pandemic, and how similar methods might be implemented and utilized to assess injury patterns in Canadian systems in future events.

Limitations

While this review provides a comprehensive overview of unintentional injuries during COVID-19 restrictions, there are limitations to note. First, the database searches included results from December 2019–July 2021 and newer studies have likely been published that are not included in this review, particularly from a Canadian perspective. These studies could provide additional insights into injury patterns in Canada, which would allow for comparison to global trends. Further, the studies included in this review compared COVID-19 periods to pre-lockdown phases; however, few comparisons were made to periods when restrictions were lifted. These outcomes would be of particular interest given that a few studies reported a “rebound” to previous injury levels when restrictions eased. As restrictions eased populations were permitted to spend more time outdoors engaging in distanced activities, and return to other activities of daily living, which may have led to an increase in injuries. Future research could investigate the pattern of injury trends following the relaxing of COVID-19 public health measures.

Conclusion

This scoping review provides an updated and comprehensive summary of information on injury epidemiology during COVID-19 in Canada and across the globe, and reports on the early changes in injury patterns with regard to location, type, and severity of injuries during COVID-19 compared to before the pandemic period. The data show important injury trends that may require additional monitoring over the next few years as we return to pre-pandemic levels of engagement in community and workplace participation.

In addition, this review identifies key target areas to guide policy making and capacity planning, as well as public education. Although populations may have experienced fatigue related to health and safety messaging given the surplus of COVID-19 information disseminated during lockdown, it is important to also provide consistent education and reminders related to safety at home and during activities of daily living. The insights generated from this review can be used to inform interventions and policies to identify system gaps and reduce injury in populations, worldwide.

Author contributions

SK: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. OR: Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. WT: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SM: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. IP: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding Statement

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1385452/full#supplementary-material

References

- 1.World Health Organization . Coronavirus disease (COVID-19). (2023). Available at: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/question-and-answers-hub/q-a-detail/coronavirus-disease-covid-19.

- 2.Canadian Institute for Health Information . Canadian COVID-19 intervention timeline. (2023). Available at: https://www.cihi.ca/en/canadian-covid-19-intervention-timeline

- 3.HealthLinkBC . Injury prevention during COVID-19. (2022). Available at: https://www.healthlinkbc.ca/more/health-features/coronavirus-disease-covid-19/injury-prevention-covid.

- 4.Piedt S, Rajabali F, Turcotte K, Barnett B, Pike I. The British Columbia casebook for injury prevention. (2015). Available at: https://www.injuryresearch.bc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/BCIRPU-Casebook-2015.pdf.

- 5.Public Health Agency of Canada . Quick facts on injury and poisoning: injury and poisoning deaths in Canada. (2022). Available at: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/injury-prevention/facts-on-injury.html.

- 6.Parachute Canada . Cost of injury in Canada. (2022). Available at: https://parachute.ca/en/professional-resource/cost-of-injury-in-canada/the-human-cost-of-injury/.

- 7.Biddison LD, Berkowitz KA, Courtney B, De Jong CMJ, Devereaux AV, Kissoon N, et al. Ethical considerations: Care of the Critically ill and Injured during Pandemics and disasters: CHEST consensus statement. Chest. (2014) 146:e145S–55S. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-0742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hick JL, Einav S, Hanfling D, Kissoon N, Dichter JR, Devereaux AV, et al. Surge capacity principles: Care of the Critically ill and Injured during Pandemics and disasters: CHEST consensus statement. Chest. (2014) 146:e1S–e16S. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-0733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Government of Canada . Health portfolio. Health Canada. (2017). Available at: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/corporate/health-portfolio.html.

- 10.Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework (2005) 8:19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616, [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen Y, Mo F, Yi QL, Jiang Y, Mao Y. Unintentional injury mortality and external causes in Canada from 2001 to 2007. Chronic Dis Inj Can. (2013) 33:95–102. doi: 10.24095/hpcdp.33.2.06, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Veritas Health Innovation . Covidence systematic review software. Melbourne, Australia. Available at: www.covidence.org.

- 13.Andreozzi V, Marzilli F, Muselli M, Previ L, Cantagalli MR, Princi G, et al. The effect of shelter-in-place on orthopedic trauma volumes in Italy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Acta Biomed Ateneo Parmense. (2021) 92:e2021216. doi: 10.23750/abm.v92i2.10827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bhat A, Kamath K. Comparative study of orthopaedic trauma pattern in covid lockdown versus non-covid period in a tertiary care Centre. J Orthop. (2021) 23:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jor.2020.11.008, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blackhall KK, Downie IP, Ramchandani P, Kusanale A, Walsh S, Srinivasan B, et al. Provision of emergency maxillofacial service during the COVID-19 pandemic: a collaborative five Centre UK study. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. (2020) 58:698–703. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2020.05.020, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bolzinger M, Lopin G, Accadbled F, Sales de Gauzy J, Compagnon R. Pediatric traumatology in “green zone” during Covid-19 lockdown: a single-center study. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. (2021) 109:102946. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2021.102946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Canzi G, De Ponti E, Corradi F, Bini R, Novelli G, Bozzetti A, et al. Epidemiology of Maxillo-facial trauma during COVID-19 lockdown: reports from the hub trauma Center in Milan. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr. 14:277–83. doi: 10.1177/1943387520983119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Christey G, Amey J, Campbell A, Smith A. Variation in volumes and characteristics of trauma patients admitted to a level one trauma Centre during national level 4 lockdown for COVID-19 in New Zealand. N Z Med J. (2020) 133:81–8. PMID: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Christey G, Amey J, Singh N, Denize B, Campbell A. Admission to hospital for injury during COVID-19 alert level restrictions. N Z Med J. (2021) 134:50–8. PMID: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ercolini A, Borgioli G, Crescioli G, Vannacci A, Lanzi C, Gambassi F, et al. Exposures and suspected intoxications during SARS-CoV-2 pandemic: Preliminary results from an Italian poison control Centre. Intern Emerg med. 2021; (Crescioli, Ercolini, Borgioli, Vannacci, Mannaioni, Lombardi) Department of Neurosciences, psychology, drug research and child health, section of pharmacology and toxicology, University of Florence, Viale G. Pieraccini, Florence 6–50139, Italy). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Dass D, Ramhamadany E, Govilkar S, Rhind JH, Ford D, Singh R, et al. How a pandemic changes trauma: epidemiology and management of trauma admissions in the UK during COVID-19 lockdown. J Emerg Trauma Shock. (2021) 14:75–9. doi: 10.4103/JETS.JETS_137_20, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Diamond S, Lundy JB, Weber EL, Lalezari S, Rafijah G, Leis A, et al. A call to arms: emergency hand and upper-extremity operations during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Hand Surg Glob Online. (2020) 2:175–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsg.2020.05.004, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dowell RJ, Ashwood N, Hind J. Musculoskeletal attendances to a minor injury department during a pandemic. Cureus. (2021) 13:e13143. doi: 10.7759/cureus.13143, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fahy S, Moore J, Kelly M, Flannery O, Kenny P. Analysing the variation in volume and nature of trauma presentations during COVID-19 lockdown in Ireland. Bone Jt Open. (2020) 1:261–6. doi: 10.1302/2633-1462.16.BJO-2020-0040.R1, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fortane T, Bouyer M, Le Hanneur M, Belvisi B, Courtiol G, Chevalier K, et al. Epidemiology of hand traumas during the COVID-19 confinement period. Injury. (2021) 52:679–85. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2021.02.024, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gilmartin S, Barrett M, Bennett M, Begley C, Chroinin CN, O’Toole P, et al. The effect of national public health measures on the characteristics of trauma presentations to a busy paediatric emergency service in Ireland: a longitudinal observational study. Ir J Med Sci. (2022) 191:589–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hampton M, Clark M, Baxter I, Stevens R, Flatt E, Murray J, et al. The effects of a UK lockdown on orthopaedic trauma admissions and surgical cases: a multicentre comparative study. Bone Jt Open. (2020) 1:137–43. doi: 10.1302/2633-1462.15.BJO-2020-0028.R1, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hashmi PM, Zahid M, Ali A, Naqi H, Pidani AS, Hashmi AP, et al. Change in the spectrum of orthopedic trauma: effects of COVID-19 pandemic in a developing nation during the upsurge; a cross-sectional study. Ann Med Surg. (2020) 60:504–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2020.11.044, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hazra D, Jindal A, Fernandes JP, Abhilash KP. Impact of the lockdown due to COVID-19 pandemic on the Spectrum and outcome of trauma in India. Indian J Crit Care Med. (2021) 25:273–8. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10071-23747, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ho E, Riordan E, Nicklin S. Hand injuries during COVID-19: lessons from lockdown. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. (2021) 74:1408–12. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2020.12.020, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ilyas N, Green A, Karia R, Sood S, Fan K. Demographics and management of paediatric dental-facial trauma in the “lockdown” period: a UK perspective. Dent Traumatol. (2021) 37:576–82. doi: 10.1111/edt.12667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liguoro I, Pilotto C, Vergine M, Pusiol A, Vidal E, Cogo P. The impact of COVID-19 on a tertiary care pediatric emergency department. Eur J Pediatr. (2021) 180:1497–504. doi: 10.1007/s00431-020-03909-9, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Le Roux G, Sinno-Tellier S, Puskarczyk E, Labadie M, von Fabeck K, Pélissier F, et al. Poisoning during the COVID-19 outbreak and lockdown: retrospective analysis of exposures reported to French poison control centres. Clin Toxicol. (2021) 59:832–9. doi: 10.1080/15563650.2021.1874402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.MacDonald DRW, Neilly DW, Davies PSE, Crome CR, Jamal B, Gill SL, et al. Effects of the COVID-19 lockdown on orthopaedic trauma: a multicentre study across Scotland. Bone Jt Open. (2020) 1:541–8. doi: 10.1302/2633-1462.19.BJO-2020-0114.R1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maleitzke T, Pumberger M, Gerlach UA, Herrmann C, Slagman A, Henriksen LS, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 shutdown on orthopedic trauma numbers and patterns in an academic level I trauma Center in Berlin, Germany. PLoS One. (2021) 16:e0246956. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0246956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maniscalco P, Ciatti C, Gattoni S, Puma Pagliarello C, Moretti G, Cauteruccio M, et al. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the emergency room and orthopedic Departments in Piacenza: a retrospective analysis. Acta Biomed Ateneo Parmense. (2020) 91:e2020028. doi: 10.23750/abm.v91i14-S.11003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Milella MS, Boldrini P, Vivino G, Grassi MC. How COVID-19 lockdown in Italy has affected type of calls and Management of Toxic Exposures: a retrospective analysis of a poison control center database from march 2020 to may 2020. J Med Toxicol. (2021) 17:250–6. doi: 10.1007/s13181-021-00839-2, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nia A, Popp D, Diendorfer C, Apprich S, Munteanu A, Hajdu S, et al. Impact of lockdown during the COVID-19 pandemic on number of patients and patterns of injuries at a level I trauma center. Wien Klin Wochenschr. (2021) 133:336–43. doi: 10.1007/s00508-021-01824-z, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oliver-Welsh L, Richardson C, Ward DA. The hidden dangers of staying home: a London trauma unit experience of lockdown during the COVID-19 virus pandemic. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. (2021) 103:160–6. doi: 10.1308/rcsann.2020.7066, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Paiva M, Rao V, Spake CSL, King VA, Crozier JW, Liu PY, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on plastic surgery consultations in the emergency department. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. (2020) 8:e3371. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000003371, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pichard R, Kopel L, Lejeune Q, Masmoudi R, Masmejean EH. Impact of the COronaVIrus disease 2019 lockdown on hand and upper limb emergencies: experience of a referred university trauma hand Centre in Paris, France. Int Orthop. (2020) 44:1497–501. doi: 10.1007/s00264-020-04654-2, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pidgeon TE, Parthiban S, Malone P, Foster M, Chester DL. Injury patterns of patients with upper limb and hand trauma sustained during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown in the UK: a retrospective cohort study. Hand Surg Rehabil. (2021) 40:235–40. doi: 10.1016/j.hansur.2021.03.002, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Poggetti A, Del Chiaro A, Nucci AM, Suardi C, Pfanner S. How hand and wrist trauma has changed during covid-19 emergency in Italy: incidence and distribution of acute injuries. What to learn? J Clin Orthop Trauma. (2021) 12:22–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jcot.2020.08.008, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rachuene PA, Khanyile SM, Phala MP, Mariba MT, Masipa RR, Dey R, et al. The impact of COVID-19 national lockdown on orthopaedic trauma admissions in the northern part of South Africa: a multicentre review of tertiary- and secondary-level hospital admissions. S Afr Med J. (2021) 111:668–73. doi: 10.7196/SAMJ.2021.v111i7.15581, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Raitio A, Ahonen M, Jaaskela M, Jalkanen J, Luoto TT, Haara M, et al. Reduced number of pediatric orthopedic trauma requiring operative treatment during COVID-19 restrictions: a Nationwide cohort study. Scand J Surg. (2021) 110:254–7. doi: 10.1177/1457496920968014, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Regas I, Bellemere P, Lamon B, Bouju Y, Lecoq FA, Chaves C. Hand injuries treated at a hand emergency center during the COVID-19 lockdown. Hand Surg Rehabil. (2020) 39:459–61. doi: 10.1016/j.hansur.2020.07.001, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rozenfeld M, Peleg K, Givon A, Bala M, Shaked G, Bahouth H, et al. COVID-19 changed the injury patterns of hospitalized patients. Prehosp Disaster Med. (2021) 36:251–9. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X21000285, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ruzzini L, De Salvatore S, Lamberti D, Maglione P, Piergentili I, Crea F, et al. COVID-19 changed the incidence and the pattern of pediatric traumas: a single-Centre study in a pediatric emergency department. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:6573. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18126573, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sahin E, Akcali O. What has changed in orthopaedic emergency room during covid - 19 pandemic: a single tertiary center experience. Acta Med Mediterr. (2021) 37:521–5. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Salottolo K, Caiafa R, Mueller J, Tanner A, Carrick MM, Lieser M, et al. Multicenter study of US trauma centers examining the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on injury causes, diagnoses and procedures. Trauma Surg Acute Care Open. (2021) 6:e000655. doi: 10.1136/tsaco-2020-000655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Scott CEH, Holland G, Powell-Bowns MFR, Brennan CM, Gillespie M, Mackenzie SP, et al. Population mobility and adult orthopaedic trauma services during the COVID-19 pandemic: fragility fracture provision remains a priority. Bone Jt Open. (2020) 1:182–9. doi: 10.1302/2633-1462.16.BJO-2020-0043.R1, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Staunton P, Gibbons JP, Keogh P, Curtin P, Cashman JP, O’Byrne JM. Regional trauma patterns during the COVID-19 pandemic. Surgeon. (2021) 19:e49–52. doi: 10.1016/j.surge.2020.08.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stedman EN, Jefferis JM, Tan JH. Ocular trauma during the COVID-19 lockdown. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. (2021) 6:9435674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.van Aert GJJ, van der Laan L, Boonman-de Winter LJM, Berende CAS, de Groot HGW, Boele van Hensbroek P, et al. Effect of the COVID-19 pandemic during the first lockdown in the Netherlands on the number of trauma-related admissions, trauma severity and treatment: the results of a retrospective cohort study in a level 2 trauma Centre. BMJ Open. (2021) 11:e045015. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-045015, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Waseem S, Romann R, Lenihan J, Rawal J, Carrothers A, Hull P, et al. Trauma epidemiology after easing of lockdown restrictions: experience from a level-one major trauma Centre in England. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. (2021) 2021:101313350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Williams N, Winters J, Cooksey R. Staying home but not out of trouble: no reduction in presentations to the south Australian paediatric major trauma service despite the COVID-19 pandemic. ANZ J Surg. (2020) 90:1863–4. doi: 10.1111/ans.16277, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wong TWK, Hung JWS, Leung MWY. Paediatric domestic accidents during COVID-19 pandemic in Hong Kong. Surg Pract. (2021) 25:32–7. doi: 10.1111/1744-1633.12477 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wu C, Patel SN, Jenkins TL, Obeid A, Ho AC, Yonekawa Y. Ocular trauma during COVID-19 stay-at-home orders: a comparative cohort study. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. (2020) 31:423–6. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0000000000000687, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yoon YS, Chung CH, Min KH. Effects of COVID-2019 on plastic surgery emergencies in Korea. Arch Craniofac Surg. (2021) 22:99–104. doi: 10.7181/acfs.2021.00017, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhu W, Li X, Wu Y, Xu C, Li L, Yang J, et al. Community quarantine strategy against coronavirus disease 2019 in Anhui: An evaluation based on trauma center patients. Int J Infect Dis. (2020) 96:417–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.04.016, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Charlesworth JEG, Bold R, Pal R. Using ICD-10 diagnostic codes to identify “missing” paediatric patients during nationwide COVID-19 lockdown in Oxfordshire, UK. Eur J Pediatr. (2021) 180:3343–57. doi: 10.1007/s00431-021-04123-x, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.de Boutray M, Kun-Darbois JD, Sigaux N, Lutz JC, Veyssiere A, Sesque A, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 lockdown on the epidemiology of maxillofacial trauma activity: a French multicentre comparative study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. (2021) 50:750–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2020.10.005, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dolci A, Marongiu G, Leinardi L, Lombardo M, Dessi G, Capone A. The epidemiology of fractures and Muskulo-skeletal traumas during COVID-19 lockdown: a detailed survey of 17.591 patients in a wide Italian metropolitan area. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil. (2020) 11:72673. doi: 10.1177/2151459320972673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gil-Jardine C, Chenais G, Pradeau C, Tentillier E, Revel P, Combes X, et al. Trends in reasons for emergency calls during the COVID-19 crisis in the department of Gironde, France using artificial neural network for natural language classification. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. (2021) 29:55. doi: 10.1186/s13049-021-00862-w, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Keays G, Friedman D, Gagnon I. Pediatric injuries in the time of covid-19. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. (2020) 40:336–41. doi: 10.24095/hpcdp.40.11/12.02, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Matthay ZA, Kornblith AE, Matthay EC, Sedaghati M, Peterson S, Boeck M, et al. The DISTANCE study: determining the impact of social distancing on trauma epidemiology during the COVID-19 epidemic-An interrupted time-series analysis. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. (2021) 90:700–7. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000003044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Morris D, Rogers M, Kissmer N, Du Preez A, Dufourq N. Impact of lockdown measures implemented during the Covid-19 pandemic on the burden of trauma presentations to a regional emergency department in Kwa-Zulu Natal, South Africa. Afr J Emerg Med. (2020) 10:193–6. doi: 10.1016/j.afjem.2020.06.005, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Reuter H, Jenkins LS, De Jong M, Reid S, Vonk M. Prohibiting alcohol sales during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic has positive effects on health services in South Africa. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med. (2020) 12:e1–4. doi: 10.4102/phcfm.v12i1.2528, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ruiz-Medina PE, Ramos-Melendez EO, Cruz-De La Rosa KX, Arrieta-Alicea A, Guerrios-Rivera L, Nieves-Plaza M, et al. The effect of the lockdown executive order during the COVID-19 pandemic in recent trauma admissions in Puerto Rico. Inj Epidemiol. (2021) 8:22. doi: 10.1186/s40621-021-00324-y, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sephton BM, Mahapatra P, Shenouda M, Ferran N, Deierl K, Sinnett T, et al. The effect of COVID-19 on a major trauma network. An analysis of mechanism of injury pattern, referral load and operative case-mix. Injury. (2021) 52:395–401. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2021.02.035, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sherman WF, Khadra HS, Kale NN, Wu VJ, Gladden PB, Lee OC. How did the number and type of injuries in patients presenting to a regional level I trauma center change during the COVID-19 pandemic with a stay-at-home order? Clin Orthop. (2021) 479:266–75. doi: 10.1097/CORR.0000000000001484, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Silvagni D, Baggio L, Lo Tartaro Meragliotta P, Soloni P, La Fauci G, Bovo C, et al. Neonatal and pediatric emergency room visits in a tertiary center during the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy. Pediatr Rep. (2021) 13:168–76. doi: 10.3390/pediatric13020023, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wyatt S, Mohammed MA, Fisher E, McConkey R, Spilsbury P. Impact of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic and associated lockdown measures on attendances at emergency departments in English hospitals: a retrospective database study. Lancet Reg Health Eur. (2021) 2:100034. doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2021.100034, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Abdallah HO, Zhao C, Kaufman E, Hatchimonji J, Swendiman RA, Kaplan LJ, et al. Increased firearm injury during the COVID-19 pandemic: a hidden urban burden. J Am Coll Surg. (2021) 232:159–168e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2020.09.028, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ajayi B, Trompeter A, Arnander M, Sedgwick P, Lui DF. 40 days and 40 nights: clinical characteristics of major trauma and orthopaedic injury comparing the incubation and lockdown phases of COVID-19 infection. Bone Jt Open. (2020) 1:330–8. doi: 10.1302/2633-1462.17.BJO-2020-0068.R1, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Manyoni MJ, Abader MI. The effects of the COVID-19 lockdown and alcohol restriction on trauma-related emergency department cases in a south African regional hospital. Afr J Emerg Med. (2021) 11:227–30. doi: 10.1016/j.afjem.2020.12.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Thongchuam C, Mahawongkajit P, Kanlerd A. The effect of the COVID-19 on corrosive ingestion in Thailand. Open Access Emerg Med. (2021) 13:299–304. doi: 10.2147/OAEM.S321218, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yeung E, Brandsma DS, Karst FW, Smith C, Fan KFM. The influence of 2020 coronavirus lockdown on presentation of oral and maxillofacial trauma to a Central London hospital. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. (2021) 59:102–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2020.08.065, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Figueroa JM, Boddu J, Kader M, Berry K, Kumar V, Ayala V, et al. The effects of lockdown during the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic on Neurotrauma-related hospital admissions. World Neurosurg. (2021) 146:e1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2020.08.083, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Williams TC, Haseeb H, Macrae C, Guthrie B, Urquhart DS, Swann OV, et al. Indirect effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on paediatric healthcare use and severe disease: a retrospective national cohort study. Arch Dis Child. (2021) 106:911–7. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2020-321008, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Monash University . Injuries during the COVID-19 pandemic, pp. 1–16. (2020). Available at: https://www.monash.edu/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/2246604/COVID-19-VISU-Bulletin-2.pdf.

- 82.Public Health Insider . New report shows increases in cardiovascular, diabetes, unintentional injury deaths, as well as homicides in King County. (2021). Available at: https://publichealthinsider.com/2021/02/04/new-report-shows-increases-in-cardiovascular-diabetes-unintentional-injury-deaths-as-well-as-homicides-in-king-county/.

- 83.The BulletPoints Project . COVID-19 and firearm injury and death. (2021). Available at: https://www.bulletpointsproject.org/blog/covid-19-and-firearm-injury-and-death/.

- 84.Houser C, Vlodarchyk B. Impact of COVID-19 on drowning patterns in the Great Lakes region of North America. Ocean Coastal Manage. (2021) 205:105570. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2021.105570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Johnstone H. Pandemic contributing to rise in drownings on open water, say experts. CBC news. (2020). Available at: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/ottawa/drowning-prevention-ottawa-change-focus-1.5676181.

- 86.Academic Minute . Impending impact of COVID-19 on drowning rates. (2021). Available at: https://academicminute.org/2021/05/william-d-ramos-indiana-university-bloomington-impending-impact-of-covid-19-on-drowning-rates/.

- 87.Taylor D. Weekly roundup: Kelowna COVID-19 cases grow to 159, drowning incidents increase in Okanagan, COVID-19 testing expanded in Kelowna. Kelowna capital news. (2020). Available at: https://www.kelownacapnews.com/news/weekly-roundup-kelowna-covid-19-cases-grow-to-159-drowning-incidents-increase-in-okanagan-covid-19-testing-expanded-in-kelowna-3202409.

- 88.Premier Health Now . How to reduce drowning risk during pandemic. (2020). Available at: https://www.premierhealth.com/your-health/articles/healthnow/how-to-reduce-drowning-risk-during-pandemic.

- 89.Water Safety New Zealand . COVID-19 and its social impact on drowning. (2020). Available at: https://watersafety.org.nz/social-impact-of-covid19-on-drowning.

- 90.Yasseen A, Weiss D, Remer S, Dobbin N, Macneill M, Bogeljic B, et al. Increases in exposure calls related to selected cleaners and disinfectants at the onset of the covid-19 pandemic: data from Canadian poison centres. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. (2021) 1:25–9. doi: 10.24095/hpcdp.41.1.03 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Gielen AC, Bachman G, Badaki-Makun O, Johnson RM, McDonald E, Omaki E, et al. National survey of home injuries during the time of COVID-19: who is at risk? Inj Epidemiol. (2020) 7:63. doi: 10.1186/s40621-020-00291-w, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Giordano F, Pennisi L, Fidente RM, Spagnolo D, Mancinelli R, Lepore A, et al. The National Institute of health and the Italian poison centers network: results of a collaborative study for the surveillance of exposures to chemicals. Ann Ig. (2022) 34:137–49. doi: 10.7416/ai.2021.2454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Yip L, Bixler D, Brooks DE, Clarke KR, Datta SD, Dudley S, et al. Serious adverse health events, including death, associated with ingesting alcohol-based hand sanitizers containing methanol–Arizona and New Mexico, may–June 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. (2020) 69:1070–3. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6932e1, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Gibson C. COVID-19: unintended poisonings from hand sanitizer, cleaning products increase 73% in Alberta. Global BC. (2021). Available at: https://globalnews.ca/news/7711132/alberta-covid-19-hand-sanitizer-cleaning-product-poisonings/.

- 95.Chang A., Schnall A. H., Law R., Bronstein A. C., Marraffa J. M., Spiller H. A., et al. Cleaning and disinfectant chemical exposures and temporal associations with COVID-19–National Poison Data System, United States, January 1, 2020–March 31, 2020. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2020). Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm6916e1.htm. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 96.Marchitelli R. Canadians are accidentally poisoning themselves while cleaning to prevent COVID-19. CBC news. (2020). Available at: https://www.cbc.ca/news/health/covid-19-accidental-poisoning-cleaning-products-1.5552779.

- 97.Coleman A. “Hundreds dead” because of COVID-19 misinformation. BBC news. (2020). Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-53755067.

- 98.Kluger J. As disinfectant use soars to fight coronavirus, so do accidental poisonings. Time magazine. (2020). Available at: https://time.com/5824316/coronavirus-disinfectant-poisoning/.

- 99.Lopez C. People are poisoning themselves trying to treat or prevent COVID-19 with a horse de-worming drug. Business insider. (2021). Available at: https://www.businessinsider.in/science/news/people-are-poisoning-themselves-trying-to-treat-or-prevent-covid-19-with-a-horse-de-worming-drug/articleshow/81234315.cms.

- 100.Imanaliyeva A. Kyrgyzstan: president prescribes poison root for COVID-19. Eurasianet. (2021). Available at: https://eurasianet.org/kyrgyzstan-president-prescribes-poison-root-for-covid-19.

- 101.ANSES . COVID-19: beware of poisoning linked to disinfection and other risk situations. (2020). Available at: https://www.anses.fr/en/content/covid-19-beware-poisoning-linked-disinfection-and-other-risk-situations.

- 102.Cousins B. Poison centres report spikes in chemical exposure calls during height of COVID-19. CTV news. (2020). Available at: https://www.ctvnews.ca/health/coronavirus/poison-centres-report-spikes-in-chemical-exposure-calls-during-height-of-covid-19-1.5119398.

- 103.Collie M. Accidental poisonings from cleaning supplies on the rise during COVID-19 outbreak. Global news BC. (2020). Available at: https://globalnews.ca/news/6905692/coronavirus-cleaning-poisonings/.

- 104.The Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids) . Ontario poison Centre warns of risks of mushroom foraging, a COVID-19 pastime gaining popularity. (2020). Available at: https://www.sickkids.ca/en/news/archive/2020/ontario-poison-centre-warns-of-risks-of-mushroom-foraging-a-covid-19-pastime-gaining-popularity/.

- 105.Poison control sees spike in calls for cleaner, disinfectant accidents amid COVID-19 pandemic. Live science. (2021). Available at: https://www.livescience.com/covid-19-cleaning-chemical-exposure.html.

- 106.Radwan CM. COVID-19: poison control centers report surge in accidental poisonings from cleaning products. Contemporary pediatrics. (2020) Available at: https://www.contemporarypediatrics.com/view/covid-19-poison-control-centers-report-surge-accidental-poisonings-cleaning-products.

- 107.WebMD . Disinfectant-linked poisoning rises amid COVID-19. WebMD. (2020). Available at: https://www.webmd.com/lung/news/20200421/disinfectant-linked-poisoning-risea-amid-covid19#1.

- 108.Ibrahim Y, Huq S, Shanmuganathan K, Gille H, Buddhdev P. Trampolines injuries are bouncing back. Bone Jt Open. (2021) 2:86–92. doi: 10.1302/2633-1462.22.BJO-2020-0152.R1, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Sugand K, Park C, Morgan C, Dyke R, Aframian A, Hulme A, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on paediatric orthopaedic trauma workload in Central London: a multi-Centre longitudinal observational study over the “golden weeks”. Acta Orthop. (2020) 91:633–8. doi: 10.1080/17453674.2020.1807092, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Baxter I, Hancock G, Clark M, Hampton M, Fishlock A, Widnall J, et al. Paediatric orthopaedics in lockdown: a study on the effect of the SARS-Cov-2 pandemic on acute paediatric orthopaedics and trauma. Bone Jt Open. (2020) 1:424–30. doi: 10.1302/2633-1462.17.BJO-2020-0086.R1, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Mohn T. Bicycle and trampoline fractures spike among kids during Covid-19, new study finds. Forbes. Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/tanyamohn/2020/05/31/bicycle-and-trampoline-fractures-spike-among-kids-during-covid-19-new-study-finds/?sh=14d26b61791c.

- 112.Buddhdev P. The Paediatric trauma burden of UK lockdown – early results in the COVID-19 era. British Orthopaedic Association (2020). Available at: https://www.boa.ac.uk/resource/the-paediatric-trauma-burden-of-uk-lockdown-early-results-in-the-covid-19-era.html.

- 113.Forani J. Trampolines jumping off shelves amid spring isolation, but are they safe? CTV news. (2020). Available at: https://www.ctvnews.ca/lifestyle/trampolines-jumping-off-shelves-amid-spring-isolation-but-are-they-safe-1.4950635.

- 114.Kham Kim. The rise of pediatric injuries at home. (2020). Available at: https://www.utphysicians.com/the-rise-of-pediatric-injuries-at-home/.

- 115.Atia F, Pocnetz S, Selby A, Russell P, Bainbridge C, Johnson N. The effect of the COVID-19 lockdown on hand trauma surgery utilization. Bone Jt Open. (2020) 1:639–43. doi: 10.1302/2633-1462.110.BJO-2020-0133.R1, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Lubbe RJ, Miller J, Roehr CA, Allenback G, Nelson KE, Bear J, et al. Effect of statewide social distancing and stay-at-home directives on Orthopaedic trauma at a southwestern level 1 trauma center during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Orthop Trauma. (2020) 34:e343–8. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000001890, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Mohan K, McCabe P, Mohammed W, Hintze J, Raza H, O’Daly B, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on pelvic and acetabular trauma: experiences from a National Tertiary Referral Centre. Cureus. (2021) 13:15833. doi: 10.7759/cureus.15833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Bizzoca D, Vicenti G, Rella C, Simone F, Zavattini G, Tartaglia N, et al. Orthopedic and trauma care during COVID-19 lockdown in Apulia: what the pandemic could not change. Min Ortop Traumatol. (2020) 71:144–50. [Google Scholar]

- 119.Gumina S, Proietti R, Polizzotti G, Carbone S, Candela V. The impact of COVID-19 on shoulder and elbow trauma: an Italian survey. J Shoulder Elb Surg. (2020) 29:1737–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2020.05.003, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Jang B, Mezrich JL. The impact of COVID-19 quarantine efforts on emergency radiology and trauma cases. Clin Imaging. (2021) 77(cim, 8911831:250–3. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2021.04.027, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Khak M, Shakiba S, Rabie H, Naseramini R, Nabian MH. Descriptive epidemiology of traumatic injuries during the first lockdown period of COVID-19 crisis in Iran: a multicenter study. Asian J Sports Med. (2020) 11:1–5. doi: 10.5812/asjsm.103842 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Koutserimpas C, Raptis K, Tsakalou D, Papadaki C, Magarakis G, Kourelis K, et al. The effect of quarantine due to COVID-19 pandemic in surgically treated fractures in Greece: a two-center study. Medica. (2020) 15:332–4. doi: 10.26574/maedica.2020.15.3.332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Probert AC, Sivakumar BS, An V, Nicholls SL, Shatrov JG, Symes MJ, et al. Impact of COVID-19-related social restrictions on orthopaedic trauma in a level 1 trauma Centre in Sydney: the first wave. ANZ J Surg. (2021) 91:68–72. doi: 10.1111/ans.16375, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Saponaro G, Gasparini G, Pelo S, Todaro M, Soverina D, Barbera G, et al. Influence of Sars-Cov 2 lockdown on the incidence of facial trauma in a tertiary care hospital in Rome, Italy. Minerva Stomatol. (2020) 71:96–100. doi: 10.23736/S0026-4970.20.04446-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Wang CJ, Hoffman GR, Walton GM. The implementation of COVID-19 social distancing measures changed the frequency and the characteristics of facial injury: the Newcastle (Australia) experience. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr. (2021) 14:150–6. doi: 10.1177/1943387520962280, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Woo E, Smith AJ, Mah D, Pfister BF, Drobetz H. Increased orthopaedic presentations as a result of COVID-19-related social restrictions in a regional setting, despite local and global trends. ANZ J Surg. (2021) 91:1369–75. doi: 10.1111/ans.16928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Waghmare A, Shrivastava S, Date S. Effect of covid-19 lockdown in trauma cases of rural India. Int J Res Pharm Sci. (2020) 11:365–8. doi: 10.26452/ijrps.v11iSPL1.2727 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Adiamah A, Thompson A, Lewis-Lloyd C, Dickson E, Blackburn L, Moody N, et al. The ICON trauma study: the impact of the COVID-19 lockdown on major trauma workload in the UK. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. (2021) 47:637–45. doi: 10.1007/s00068-020-01593-w, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Akkoc MF, Bulbuloglu S, Ozdemir M. The effects of lockdown measures due to COVID-19 pandemic on burn cases. Int Wound J. (2021) 18:367–74. doi: 10.1111/iwj.13539, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Codner JA, De Ayala R, Gayed RM, Lamphier CK, Mittal R. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on burn admissions at a major metropolitan burn center. J Burn Care Res. (2021) 42:1103–9. doi: 10.1093/jbcr/irab106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Kruchevsky D, Arraf M, Levanon S, Capucha T, Ramon Y, Ullmann Y. Trends in burn injuries in northern Israel during the COVID-19 lockdown. J Burn Care Res. (2021) 42:135–40. doi: 10.1093/jbcr/iraa154, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Monte-Soldado A, Lopez-Masramon B, Rivas-Nicolls D, Andres-Collado A, Aguilera-Saez J, Serracanta J, et al. Changes in the epidemiologic profile of burn patients during the lockdown in Catalonia (Spain): a warning call to strengthen prevention strategies in our community. Burns. (2021) 48:228–33. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2021.03.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Sanford EL, Zagory J, Blackwell JM, Szmuk P, Ryan M, Ambardekar A. Changes in pediatric trauma during COVID-19 stay-at-home epoch at a tertiary pediatric hospital. J Pediatr Surg. (2021) 56:918–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2021.01.020, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Varma P, Kazzazi D, Anwar MU, Muthayya P. The impact of COVID-19 on adult burn management in the UK: a regional Centre experience. J Burn Care Res. (2021) 42:998–1002. doi: 10.1093/jbcr/irab015, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Yamamoto R, Sato Y, Matsumura K, Sasaki J. Characteristics of burn injury during COVID-19 pandemic in Tokyo: a descriptive study. Burns Open. (2021) 5:40–5. doi: 10.1016/j.burnso.2021.06.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Boisvert N. Toronto fire, busy and understaffed during COVID-19, eyes growth in 2021. CBC news. (2021). Available at: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/toronto-fire-2021-budget-1.5866606.

- 137.Simmons Taylor. Fires up more than 13% in Toronto amid COVID-19 pandemic, firefighters union warns. CBC news. (2020). Available at: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/toronto-fire-calls-up-1.5666141.

- 138.Bazett-Jones DM, Garcia MC, Taylor-Haas JA, Long JT, Rauh MJ, Paterno MV, et al. Impact of COVID-19 social distancing restrictions on training habits, injury, and care seeking behavior in youth Long-Distance runners. Front Sports Act Living. (2020) 2:586141. doi: 10.3389/fspor.2020.586141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Bram JT, Johnson MA, Magee LC, Mehta NN, Fazal FZ, Baldwin KD, et al. Where have all the fractures gone? The epidemiology of pediatric fractures during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Pediatr Orthop. (2020) 40:373–9. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0000000000001600, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Campbell E, Zahoor U, Payne A, Popova D, Welman T, Pahal GS, et al. The COVID-19 pandemic: the effect on open lower limb fractures in a London major trauma Centre - a plastic surgery perspective. Injury. (2021) 52:402–6. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2020.11.047, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Carkci E, Polat B, Polat A, Peker B, Ozturkmen Y. The effect of the coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic on the number and characteristics of orthopedic trauma patients in a tertiary Care Hospital in Istanbul. Cureus. (2021) 13:e12569. doi: 10.7759/cureus.12569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Crenn V, El Kinani M, Pietu G, Leteve M, Persigant M, Toanen C, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 lockdown period on adult musculoskeletal injuries and surgical management: a retrospective monocentric study. Sci Rep. (2020) 10:22442. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-80309-x, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.DeJong AF, Fish PN, Hertel J. Running behaviors, motivations, and injury risk during the COVID-19 pandemic: a survey of 1147 runners. PLoS One. (2021) 16:e0246300. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0246300, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Donovan RL, Tilston T, Frostick R, Chesser T. Outcomes of Orthopaedic trauma services at a UK major trauma Centre during a National Lockdown and pandemic: the need for continuing the provision of services. Cureus. (2020) 12:e11056. doi: 10.7759/cureus.11056, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Figueiredo LB, Araujo SCS, Martins GH, Costa SM, Amaral MBF, Silveira RL. Does the lockdown influence the Oral and maxillofacial surgery Service in a Level 1 trauma hospital during the novel coronavirus 2019 (COVID 19) Pandemia? J Craniofac Surg. (2020) 32:1002–5. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000007054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Gumina S, Proietti R, Villani C, Carbone S, Candela V. The impact of COVID-19 on shoulder and elbow trauma in a skeletally immature population: an Italian survey. JSES Int. (2021) 5:3–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jseint.2020.08.003, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Hassan K, Prescher H, Wang F, Chang DW, Reid RR. Evaluating the effects of COVID-19 on plastic surgery emergencies: protocols and analysis from a level I trauma center. Ann Plast Surg. (2020) 85:S161–5. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000002459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Hoffman GR, Walton GM, Narelda P, Qiu MM, Alajami A. COVID-19 social-distancing measures altered the epidemiology of facial injury: a United Kingdom-Australia comparative study. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. (2021) 59:454–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2020.09.006, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Holmes HH, Monaghan PG, Strunk KK, Paquette MR, Roper JA. Changes in training, lifestyle, psychological and demographic factors, and associations with running-related injuries during COVID-19. Front Sports Act Living. (2021) 3:637516. doi: 10.3389/fspor.2021.637516, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]