Abstract

Latina/o youth in the U.S. are often characterized by elevated rates of cigarette smoking and depressive symptoms, and these rates appear to vary by youth acculturation and socio-cultural stress. Scholars suggest that parents’ cultural experiences may be important determinants of youth smoking and depressive symptoms. However, few studies have examined the influence of parent acculturation and related stressors on Latina/o youth smoking and depressive symptoms. To address this gap in the literature, in the current study we investigated how parent-reported acculturation, perceived discrimination, and negative context of reception affect youth smoking and depressive symptoms through parent reports of familism values and parenting. The longitudinal (4 waves) sample consisted of 302 Latina/o parent-adolescent dyads from Los Angeles (N = 150) and Miami (N = 152). Forty-seven percent of the adolescent sample was female (M age = 14.5 years), and 70% of the parents were mothers (M age = 41.10 years). Parents completed measures of acculturation, perceived discrimination, negative context of reception, familism values, and parenting. Youth completed measures regarding their smoking and symptoms of depression. Structural equation modeling suggested that parents’ collectivistic values (Time 1) and perceived discrimination (Time 1) predicted higher parental familism (Time 2), which in turn, predicted higher levels of positive/involved parenting (Time 3). Positive/involved parenting (Time 3), in turn, inversely predicted youth smoking (Time 4). These findings indicate that parents’ cultural experiences play important roles in their parenting, which in turn appears to influence Latino/a youth smoking. This study highlights the need for preventive interventions to attend to parents’ cultural experiences in the family (collectivistic values, familism values, and parenting) and the community (perceived discrimination).

Keywords: Acculturation, Latino/a families, Smoking, Depression, Stress, Parenting

1. Introduction

Adolescence is a developmental period marked by high risk for cigarette smoking, the leading cause of preventable death in the U.S. (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2014). Cigarette smoking also often co-occurs with depressive symptoms (Beal, Negriff, Dorn, Pabst, & Schulenberg, 2014), and depressive symptoms can become a chronic and serious condition (Pratt & Brody, 2014). Reasons for the co-occurrence of cigarette smoking and symptoms of depression are not fully understood. Although some studies suggest that individuals use cigarettes to self-medicate their depressive symptoms (e.g., Maslowsky & Schulenberg, 2013), other studies indicate the opposite, that nicotine/smoking leads to depressive symptoms through various mechanisms (e.g., Beal et al., 2014; Quattrocki, Baird, & Yurgelun-Todd, 2000). Still others have argued against a causal relationship between smoking and depression, proposing that depression and smoking are simply influenced by common factors such as stress (Kendler et al., 1993). Although there is controversy regarding the causal models involving smoking and depressive symptoms, most people who smoke start smoking during adolescence (Prokhorov et al., 2006), and the majority of people experience depressive symptoms for the first time before age 18 (Weersing & Brent, 2006). Given that Latina/o youth are often characterized by elevated smoking and depressive symptomatology, it is important to understand factors that contribute to these youth outcomes.

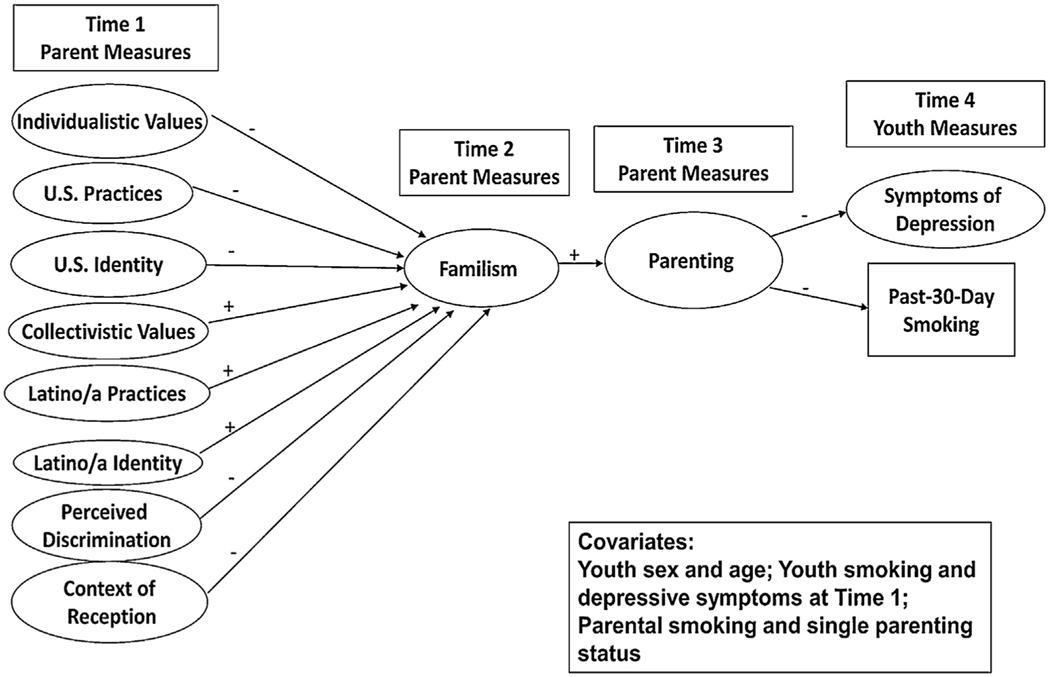

Prior research on Latina/o youth smoking and depressive symptoms has focused on the roles of youth acculturation, youth socio-cultural stressors (e.g., perceived discrimination and negative context of reception), and youth-reported family processes (e.g., familism values and parenting strategies; Cano et al., 2015; Gerdes & Lawton, 2014; Lorenzo-Blanco, Unger, Baezconde-Garbanati, Ritt-Olson, & Soto, 2011, 2012). Much less is known about the influence of parents’ acculturation and parents’ socio-cultural stress on family processes and youth smoking and depressive symptoms. Theory and empirical research suggest that parents’ acculturation and socio-cultural stressors may influence youth smoking and depressive symptoms, possibly by influencing parents’ familism values and parenting (Conger, Conger, & Martin, 2010; Santisteban, Coatsworth, Briones, Kurtines, & Szapocznik, 2012). To investigate this possibility and the processes through which parent acculturation and parent socio-cultural stress (i.e., perceived discrimination and negative context of reception) may influence smoking and depressive symptoms in Latina/o youth, we integrated empirical research and theory on acculturation, socio-cultural stress, and family into a hypothesized process-oriented model (see Fig. 1). This model draws on parent acculturation (U.S. and Latino/a cultural values, practices, and identifications) and parent socio-cultural stress (perceived discrimination and negative context of reception) as influences on youth smoking and depressive symptoms through parent-reported familism values and parenting.

Fig. 1.

Theoretical model showing all expected relationships and their predicted valence.

1.1. Acculturation: dimensions and domains

Acculturation refers to the cultural, social, behavioral, and psychological changes experienced by individuals and groups of individuals when they come into continuous contact with new receiving cultural contexts (Schwartz, Unger, Zamboanga, & Szapocznik, 2010). Acculturation has been described as a bi-dimensional process that consists of both receiving culture acquisition and heritage culture retention/acquisition (Berry, 1997). Latina/o families in the United States can learn about and continue to adhere to elements of their Latina/o heritage culture while also learning about and adopting elements of U.S. culture (Padilla & Perez, 2003; Lorenzo-Blanco & Cortina, 2013). As such, acculturation can affect values, beliefs, and parenting behaviors among parents (Ogbu, 1994; Santisteban & Mitrani, 2003; Santisteban et al., 2012), which in turn can influence the well-being of Latina/o youth (whose well-being often depends on their parents; Coleman, 2011). Parent acculturation may, for example, influence parents’ familism values and parenting strategies, which, in turn, may impact the well-being of Latina/o youth (Gerdes & Lawton, 2014; Ogbu, 1994; Santisteban et al., 2012).

Acculturation also consists of multiple domains. Schwartz et al. (2010) proposed a bi-dimensional and multi-domain model of acculturation in which receiving-culture acquisition and heritage-culture retention each operate within three separate yet related cultural domains. Receiving-culture acquisition domains include orientations towards U.S. practices (e.g., English language acquisition, consuming U.S. media and foods), U.S. cultural values (e.g., individualism and independence), and U.S. identity (e.g., identifying as American). Heritage-culture retention domains include orientations towards Latino/a practices (e.g., Spanish language acquisition, retention and use; consuming Latino/a media and foods), Latino/a cultural values (e.g., collectivistic values and a focus on interdependence), and Latino/a ethnic identity (e.g., identifying as Latino/a, Mexican, Cuban, and so on). Latina/o parents may adhere to some Latina/o and U.S. acculturation components (i.e., Latina/o and/or U.S. practices, values, identifications) but not others. Identifying which specific parent acculturation components link with family processes, youth smoking, and depressive symptoms can provide insights into where to best intervene to prevent or reduce youth smoking and depressive symptoms.

1.2. Acculturation and family processes

Acculturation can be linked with disrupted family functioning (Falicov, 2014; Ho, 2010; Tingvold, Middelthon, Allen, & Hauff, 2012), which in turn may increase risks for smoking and depressive symptoms among youth (Gerdes & Lawton, 2014). Studies indicate that acculturation may influence the degree to which Latina/o parents endorse family values such as “familism” (Miranda, Estrada, & Firpo-Jimenez, 2000), which emphasizes trust, family loyalty, and a general orientation toward the family, and it is thought that familism promotes positive, interpersonal family relationships, high family unity, and social support (Rivera et al., 2008). Consistent with this notion, research with Latina/o adolescents indicates that familism is associated with greater parental monitoring (Romero & Ruiz, 2007; Van Campen & Romero, 2012) and more positive/involved parenting (Santisteban et al., 2012), which in turn, appears to predict lower youth problem behavior.

Moreover, studies with Latina/o adults indicate that familism values relate with higher levels of family cohesion and lower levels of family conflict (Lorenzo-Blanco & Cortina, 2013), suggesting that familism may promote a positive family life. Additionally, in research with Latina/o youth, familism values related with lower youth smoking and depressive symptoms (Lorenzo-Blanco et al., 2012), but less is known regarding how parents’ familism values influence youth smoking and depressive symptoms.

Scholars propose that, with acquisition of U.S. culture (often measured as cultural practices), familism may erode, possibly leading to less positive family relationships (Miranda et al., 2000), thereby increasing youth’s risk for smoking and depressive symptoms (Gerdes & Lawton, 2014). The current study tests this proposition, while also examining the role of parent socio-cultural stress on youth smoking and depressive symptoms by way of family processes.

1.3. Parent socio-cultural stress and family processes

Cultural scholars recommend going beyond measures of acculturation by also assessing the influence of socio-cultural stressors on family processes and youth well-being (Gerdes & Lawton, 2014; Santisteban, Mena, & Abalo, 2013). For example, Betancourt and Lopez (1993) argue that acculturation may not adequately assess the influence of U.S. and Latino/a cultural practices, values, and identifications on family processes and youth well-being because measures of acculturation may be confounded with everyday stressors that accompany life in the United States for Latina/o immigrants. These socio-cultural stressors include perceived discrimination and a negative context of reception (e.g., Lueck and Wilson, 2011).

Perceived discrimination has been defined as perceived experiences of unfair, differential treatment (Perez, Fortuna, & Alegría, 2008), and context of reception refers to the opportunity structures available for immigrants in the U.S., such as access to good employment and schools (Portes & Rumbaut, 2006). Parents’ experiences of perceived discrimination and a negative context of reception may be distressing to them, and it stands to reason that, over time, these negative experiences may become chronic, daily stressors that may impact parents’ own adjustment and parenting, thereby indirectly influencing youth well-being (Conger et al., 2010).

Empirical research indicates that parents’ own stress may negatively impact family processes and indirectly impact youth well-being (Conger et al., 2010). Moreover, in research with Latino/a adolescent males (Gil, Wagner, & Vega, 2000), socio-cultural stress was associated with lower familism, and lower familism was linked with more substance use. These findings suggest that youth socio-cultural stress may link with lower familism. However, less is known how parents’ socio-cultural stress influences their own familism values and parenting. Accordingly, in the current longitudinal study we investigate how parent acculturation and parent socio-cultural stress influences parents’ familism and parenting to influence youth smoking and symptoms of depression.

2. The current study: the role of parent acculturation and socio-cultural stress

Studies of youth acculturation suggest that U.S. culture acquisition may increases risk for smoking and depressive symptoms, whereas heritage culture retention/acquisition may decrease these risks (Epstein, Botvin, & Diaz, 1998; Lorenzo-Blanco et al., 2011). Moreover, studies with Latina/o youth suggest that youth-reported perceived discrimination and negative context of reception are associated with elevated youth smoking and depressive symptoms (Lorenzo-Blanco et al., 2011; Schwartz, Unger, Lorenzo-Blanco et al., 2014). However, missing from prior work is a family-systems perspective. Previous studies have investigated how youth acculturation and youth socio-cultural stress impacts youth smoking and depressive symptoms and have paid little attention to how parents’ acculturation and parents’ socio-cultural stress influences youth cigarette smoking and depressive symptoms.

The current four-wave longitudinal study addresses this gap in the literature by combining empirical research and theory on acculturation, socio-cultural stress, family processes, and youth smoking and depressive symptoms into a conceptual, process-oriented model (Fig. 1), which leads from parent acculturation and parent socio-cultural stress to youth smoking and depressive symptoms through parent familism values and parenting. We tested this model using a sample of recent immigrant Latina/o parents and their adolescent children. Additionally, we employed a bidimensional/multi-domain model of parent acculturation, which allowed us to identify those specific parent acculturation components that predict family processes, which in turn influence youth smoking and depressive symptoms. Generally, we hypothesized that parent acculturation and socio-cultural stressors would influence youth smoking and symptoms of depression by influencing parent familism values and parenting behaviors. Specifically, we proposed the following hypotheses (Fig. 1):

Parents’ higher acquisition and maintenance of U.S. receiving culture (practices, identity, and individualistic values) and higher socio-cultural stress (i.e., perceived discrimination and a negative context of reception) at Time 1 will be associated with lower parent familism at Time 2, which will relate with more positive/involved parenting at Time 3, which in turn, will predict lower youth smoking and depressive symptoms at Time 4.

Parents’ higher maintenance of Latino/a culture (practices, Latino/a ethnic identity, and collectivistic values) and lower socio-cultural stress (i.e., perceived discrimination and negative context of reception) at Time 1 will lead to higher parent familism at Time 2, which will relate with more positive/involved parenting at Time 3, which in turn, will predict lower youth smoking and depressive symptoms at Time 4.

Parent familism at Time 2 will mediate the relationship between parent acculturation components and parent socio-cultural stress (i.e., perceived discrimination and a negative context of reception) at Time 1 and positive/involved parenting at Time 3.

Positive/involved parenting at Time 3 will mediate the relationship between parent familism at Time 2 and youth-reported cigarette smoking and depressive symptoms at Time 4.

Fig. 1 summarizes this collection of hypotheses, illustrating which relationships were expected (as indicated by an arrow between constructs) and the anticipated direction of each relationship (positive or negative).

3. Method

3.1. M Sample

Participants included 302 parent-adolescent dyads from Los Angeles (N = 150) and Miami (N = 152). About half the adolescent sample (47%) was female, and the mean adolescent age at baseline was 14.51 years (SD = 0.87). Each adolescent participated with a primary parent. Parents included mothers (70%), fathers (25%), stepparents (3%), and grandparents/other relatives (2%). The mean parent age was 41.09 years (SD = 7.09). Approximately 80% of parents reported annual incomes of less than $25,000, 79% of parents had graduated from high school, and 71% reported living with a partner. Most of the Los Angeles families were from Mexico (70%), and most Miami families were from Cuba (61%). Almost all of the students (98%) and parents (98%) reported Spanish as their “first or usual language”; 82% of students and 87% parents reported “speaking mostly Spanish at home” and 16% of the students and 11% of parents reported speaking “English and Spanish about the same at home.”

3.2. Procedures

3.2.1. Participant recruitment

Families were recruited from randomly selected schools (10 in Miami and 13 in Los Angeles) where the student body was at least 75% Latino/a. We selected Miami and Los Angeles as data collection sites because these cities attract Latino/a immigrants from different countries of origin and differ with regard to the context into which recent immigrants enter (Schwartz, Unger, Des Rosiers et al., 2014; Schwartz, Unger, Lorenzo-Blanco et al., 2014). We also aimed at testing a model that would capture the experiences of Latina/o families from diverse contexts. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the University of Miami and the University of Southern California, and by each participating school district.

Latina/o students were recruited from English for Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL) classes, as well as from the overall student body. Interested students provided their parent/guardian’s phone number. We obtained contact information for 632 students and their parents. Of these 632 families, 435 were reachable by phone, whereas the remaining 197 were unreachable due to incorrect or non-working telephone numbers. Of the 435 families reached by home, 303 participated at baseline. The retention rate was 85% through all waves (92% in Miami and 77% in Los Angeles). A more detailed description of the school selection and participant recruitment has been described elsewhere (Schwartz, Unger, Des Rosiers et al., 2014; Schwartz, Unger, Lorenzo-Blanco et al., 2014).

3.2.2. Assessment procedures

Baseline data were gathered during the summer of 2010. Subsequent time points occurred during Spring 2011, Fall 2011, and Spring 2012. Participants completed the assessment in English or Spanish, according to their preference. Almost all (98–99%) of parents completed their assessments in Spanish at all timepoints. Eighty-four percent of adolescents completed their assessments in Spanish at baseline. This percentage decreased to 77% at Time 2, 73% at Time 3, and 68% at Time Assessments were completed using an audio computer-assisted interviewing (A-CASI) system (Turner et al., 1998). As incentives, parents received $40 at baseline and an additional $5 at each time subsequent time point. Adolescents received a voucher for a movie ticket at each time point. Parents provided informed consent for themselves and their adolescents. Adolescents provided informed assent.

3.3. Measures

As part of the translation process, because we anticipated that research participants would come from different Latin American countries and settle in different parts of the U.S., we used four translators (two from each site). This allowed us to take into account the variations in the Spanish language based on country of origin. The two Miami translators worked together to translate the English version into Spanish, and the two Los Angeles translators reviewed the translations. The four translators discussed language discrepancies and any words that would not be understood equally by Spanish speakers across sites (Miami and Los Angeles). The Spanish that was used in the surveys is known as “broadcast Spanish,” which is the type of Spanish frequently used in the media and can be understood by most Spanish speakers.

3.3.1. Acculturation

Latino/a and U.S. cultural practices were measured using the Bicultural Involvement Questionnaire—short form that has been validated and used with U.S. Latina/o parents and youth (BIQ-S; Guo, Suarez-Morales, Schwartz, & Szapocznik, 2009). Twelve items assessed American practices and 12 assessed Latino/a practices. Parents indicated, on a scale ranging from 0 (Not at all) to 5 (Very), how much they agreed with each statement. Sample items included “I enjoy American-oriented places” and “I speak Spanish at home.” Cronbach’s alphas at baseline for U.S. practices were 0.84 in English and 0.92 in Spanish. Cronbach’s alphas at baseline for Latina/o practices were 0.97 in English and 0.89 in Spanish.

Individualistic and collectivistic cultural values were assessed with eight items assessing collectivism and eight items assessing individualism (Triandis & Gelfand, 1998). This measure has been validated with Latino/a emerging adults (Schwartz, Zamboanga, Rodriguez, & Wang, 2007) and has been previously employed with Latino/a youth samples (e.g., Schwartz, Unger, Des Rosiers et al., 2014). Sample items included “I’d rather depend on myself than on others” and “I feel good when I work with others.” Response options ranged from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree). Cronbach’s alphas for individualistic values were 0.88 in English and 0.83 in Spanish. Cronbach’s alphas for collectivistic values were 0.57 in English and 0.80 in Spanish.

U.S. and Latino/a identity were assessed using the Multi-Group Ethnic Identity Measure (MEIM; Roberts et al., 1999) and the American Identity Measure (AIM; Schwartz et al., 2012). These measures have been validated across ethnically diverse samples (including Latino/as) and have been used previously with Latino/a youth (Schwartz, Unger, Des Rosiers et al., 2014; Schwartz, Unger, Lorenzo-Blanco et al., 2014). The same item structure was used for U.S. and Latino/a identity, with the exception that “the United States” or “an American” was used in place of “my ethnic group.” Sample items included “I am happy that I am a member of my ethnic group/an American.” Cronbach’s alphas for U.S. identity were 0.76 in English and 0.88 in Spanish. Cronbach’s for Latina/o identity were 0.96 in English and 0.89 in Spanish.

3.3.2. Perceived discrimination

We measured parent reports of perceived discrimination using seven items (Phinney, Madden, & Santos, 1998). This measure has been validated with ethnic minority youth and has been used with Latina/o families (Schwartz, Unger, Lorenzo-Blanco et al., 2014). A sample item included “How often do employers treat you unfairly or negatively because of your ethnic background?” Response choices ranged from 0 (Not at all) to 4 (Almost always). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.92 in English and 0.84 in Spanish.

3.3.3. Perceived negative context of reception

Six items were used to assess parents’ perceived negative context of reception (Schwartz, Unger, Des Rosiers et al., 2014; Schwartz, Unger, Lorenzo-Blanco et al., 2014). This measure has been validated for Latina/o families and has been used in previous research with Latina/o youth (Cano et al., 2015). A sample item included “It is hard for me to get good employment because of where I am from.” Response options ranged from 0 (Not at all) to 4 (Almost always). Cronbach’s alphas at baseline were 0.84 in English and 0.83 in Spanish.

3.3.4. Familism

Familism was assessed with an 18-item familism scale (Steidel & Contreras, 2003). This scale has been used previously with Latina/o parents and youth (Baumann, Kuhlberg, & Zayas, 2010). Sample items include “A person should rely on his or her family if the need arises.” Responses were provided on a scale from 0 (Strongly disagree) to 4 (Strongly agree). Cronbach’s α at Time 2 was 0.83 in English and 0.91 in Spanish.

3.3.5. Parenting

Parenting was assessed in terms of parental involvement and positive parenting (Gorman-Smith, Tolan, Zelli, & Huesman, 1996), measures that have been validated and used previously with Latina/o parents and adolescents (Santisteban et al., 2012; Schwartz et al., 2013). Parental involvement was measured using 10 items (Cronbach’s α at Time 3 = 0.91 in both English and Spanish). A sample item was “Do you find time to listen to your child when he or she wants to talk to you?” Positive parenting was assessed with six items (Cronbach’s α at Time 3 was 0.91 in English and 0.92 in Spanish). Sample items include “When your child has done something that you like or approve of, do you say something nice about it or praise or give approval?” Response options for both subscales ranged from 0 (Never) to 4 (Always).

3.3.6. Adolescent depressive symptoms

We used the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) to assess adolescents’ depressive symptoms (Radloff, 1977). The CES-D consists of 20 items, is widely used in survey studies, and has been validated with Latino youth (Crockett et al., 2005). Adolescents indicated, on a scale ranging from 0 (Strongly disagree) to 4 (Strongly agree), how they have felt during the past week. Higher scores indicate more depressive symptoms (Cronbach’s α at Time 4 was 0.80 in English and 0.88 in Spanish).

3.3.7. Adolescent smoking

Adolescents responded to the following question: “Have you smoked cigarettes in the past 30 days?” Response choices included 0 (No) and 1 (Yes).

3.3.8. Demographics

Youth age and gender were self-reported. Parents’ single parenting status was assessed with the following question: “This question is about your significant other such as husband/boyfriend or wife/girlfriend. Is there someone who is like that for you and lives in the home with you and helps you with living expenses and caring for the child in this study?” Response choices included 0 (No) and 1 (Yes). Parental smoking was assessed by asking parents to report on the how often they had smoked cigarettes during the year prior to assessment. Response choices included 0 (None), 1 (Once a month or less), 2 (Once a week), 3 (Several times a week), and 4 (Daily/nearly daily). Because the responses to this question were highly skewed, we recoded these responses to 0 (Not Smoked in the past year) and 1 (Smoked in the past year).

3.4. Data analytic strategy

We computed descriptive analyses and bivariate correlations for all study variables using SPSS version 21.0 (IBM, 2012). We used Mplus Version 7.1 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012) to estimate structural equation models. Missing data were handled in Mplus using weighted least squares estimation. Weighted least squares estimation uses all available data, except for missing variables on covariates (youth age and gender in the current study). Weighted least squares estimation is superior to listwise and pairwise deletion in terms of model estimation, reducing bias, and maximizing efficiency, and it is relatively equivalent to multiple imputation techniques (Asparouhov and Muthen, 2010). Weighted least squares estimation provides probit regression coefficients for dichotomous variables (e.g., whether or not the adolescent had smoked at Time 4). Probit regression assumes that the probability of event occurrence is normally distributed, and a standardized probit regression coefficient is similar to a standardized linear regression coefficient (Azen & Walker, 2011). We also conducted mediation analyses by calculating confidence intervals using the asymmetric distribution of products test (MacKinnon, 2008) and the Rmediation software (Tofighi & MacKinnon, 2011). This test computes a 95% confidence interval around the product of the unstandardized paths that comprise the mediating pathway. If this confidence interval does not include zero, then mediation is assumed. All of our analyses controlled for youth age, youth gender and parental smoking to rule these out as alternative explanations for our findings. We further controlled for parents’ single parenting status. We also controlled for baseline adolescent cigarette smoking and depressive symptoms so that we could assess change in these outcome variables as a result of parents’ cultural experiences and family processes.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations

Table 1 displays descriptive statistics for all study variables. Bivariate correlations among all study variables are shown in Table 2.

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics for overall sample (N = 302).

| Variables | N(%) or M (SD) | |

|---|---|---|

| Parent Acculturation (Time 1) | ||

| Individualistic Values | 20.71 | (4.60) |

| U.S. Practices | 29.74 | (13.60) |

| U.S. Identity | 28.86 | (7.15) |

| Collectivist Values | 24.20 | (3.26) |

| Latino/a Practices | 56.76 | (11.95) |

| Latino/a Identity | 33.95 | (5.66) |

| Parent Perceived Discrimination (Time 1) | 6.86 | (5.17) |

| Parent Perceived Context of Reception (Time 1) | 10.69 | (4.81) |

| Parent Familism (Time 2) | 54.55 | (7.83) |

| Parent Parenting (Time 3) | 52.36 | (8.65) |

| Youth Symptoms of Depression (Time 4) | 29.65 | (14.84) |

| Youth Past-30-day Smoking (Time 4) | 10.00 | (3.3) |

Table 2.

Intercorrelations between all Study Variables.

| Variable Name | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Age (A) | – | |||||||||||||

| 2 Gender (A) | −0.00 | – | ||||||||||||

| 3 American Practices (P) | 0.10 | −0.00 | – | |||||||||||

| 4 American Identity (P) | −0.10 | −0.08 | .15** | – | ||||||||||

| 5 Individualistic Values (P) | 0.02 | 0.04 | −0.01 | −0.02 | – | |||||||||

| 6 Hispanic Practices (P) | 0.02 | 0.03 | −0.25** | 0.03 | 0.07 | – | ||||||||

| 7 Hispanic Identity (P) | 0.07 | 0.01 | .12* | .12* | .20** | .13* | – | |||||||

| 8 Collectivistic Values (P) | 0.11 | −0.02 | 0.04 | 0.02 | .24** | .21** | .40** | – | ||||||

| 9 Perceived Discrimination (P) | 0.00 | −0.05 | −0.02 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.02 | .12* | 0.02 | – | |||||

| 10 Negative Context of Reception (P) | −0.03 | −0.05 | −0.17** | −0.12* | 0.06 | 0.06 | −0.11 | −0.07 | .51** | – | ||||

| 11 Familism (P) | −0.06 | 0.00 | −0.12* | 0.09 | .22** | 0.10 | .16** | .36** | −0.04 | −0.02 | – | |||

| 12Parenting(P) | 0.11 | 0.08 | .15* | −0.00 | 0.07 | 0.02 | .19* | .18* | −0.13* | −0.06 | .20** | – | ||

| 13CES-D (A) | 0.08 | −0.00 | −0.00 | −0.10 | −0.05 | 0.06 | −0.04 | .13* | 0.05 | −0.05 | −0.06 | −0.00 | – | |

| 14 Past30daySmoking(A) | 0.07 | −0.16* | −0.07 | −0.15* | −0.11 | −0.01 | −0.02 | 0.03 | 0.04 | −0.08 | −0.05 | −0.22** | 0.04 | – |

Note. Categorical measures: Gender, Past 30 day Smoking. A = Adolescent response, P = Parent response.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

4.2. Overall structural equation modeling (SEM)

First, we constructed parcels as indicators of latent constructs to improve the parsimony of our measurement and structural models (Little, Rhemtulla, Gibson, & Schoemann, 2013). Parceling reduces a large number of indicator items into a smaller number of parceled indicators, increasing the likelihood that the latent construct will explain the majority of the shared variability among the indicators (Little et al., 2013). After constructing these indicators, we estimated a structural equation model to test our theoretical model shown in Fig. 1. For all models, we evaluated overall fit using the comparative fit index (CFI), the chi-square test of model fit (χ2), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) (Hu and Bentler, 1998).

We used a two-stage approach to modeling (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988). In the first stage, we estimated the measurement model for the latent variables to ensure that the psychometric properties of the measures were adequate and that the items loaded on their hypothesized factors. In the second stage, we estimated the structural model (Fig. 1). The measurement model provided good fit: χ2(716) = 971.170, p < 0.001; CFI = 0.954; RMSEA = 0.034, 90% CI [.029, 0.040]. This indicated that the observed variables were good indicators of the latent variables and that all latent variables represented separate constructs. Acceptable factor loadings indicated that the observed variables were good indicators of the latent variables, and each latent variable represented a separate construct.

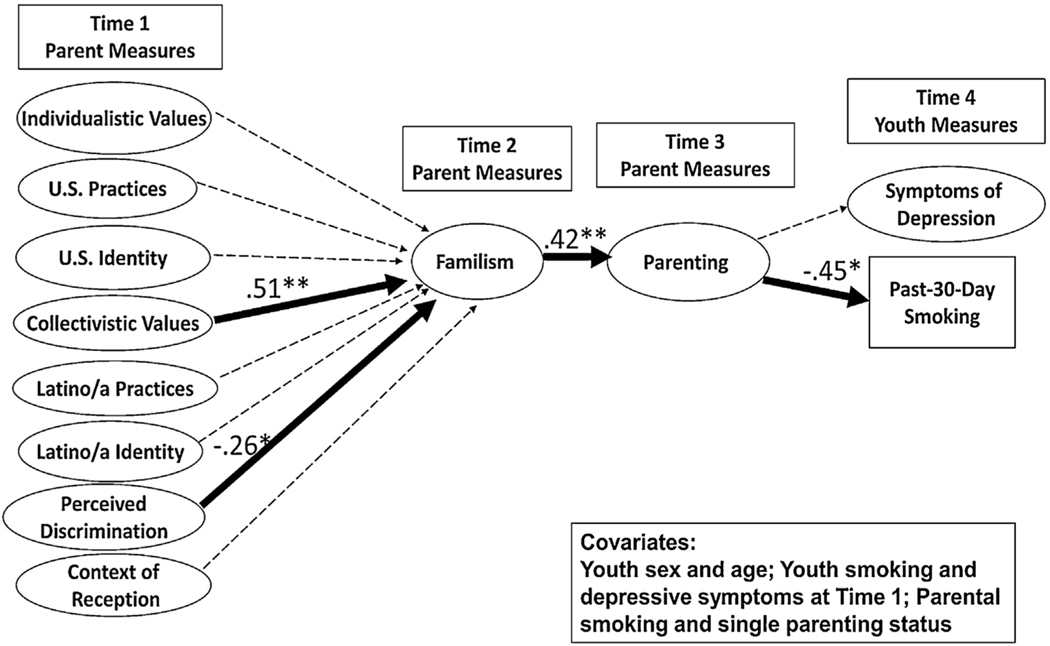

Next, we estimated the structural model (Fig. 1), which also fit the data well: χ2(1004) = 1273.799, p < 0.001; CFI = 0.934; RMSEA = 0.030, 90% CI [.025, 0.035]. As shown in Fig. 2, standardized path coefficients indicated that T1 collectivistic values predicted higher levels of familism at T2 (β = 0.51, p < 0.001) and that perceived discrimination at T1 predicted lower levels of familism at T2 (β = −0.26, p = 0.04). Familism at T2, in turn, predicted higher levels of positive and involved parenting at T3 (β = 0.42, p < 0.001), and involved parenting at T3 predicted less youth-reported smoking (β = −0.45, p = 0.02), but not depressive symptoms (β = 0.12, p = 0.14), at T4. Overall, our results suggest two potential pathways leading from parents’ cultural experiences to youth smoking. One pathway leads from collectivist values to youth smoking by way of familism and positive/involved parenting. The other pathway leads from perceived discrimination to youth smoking by way of familism and parenting. High endorsement of collectivist values and low levels of perceived discrimination among parents appear to lead to the most favorable youth outcomes.

Fig. 2.

Results with the overall sample (N = 302). Note. Dashed lines indicate non-significant paths. We controlled for youth sex, youth age, and single parenting status in all the structural paths. We controlled for youth depressive symptoms at Time 1 in the path from parenting to depressive symptoms. We controlled for youth cigarette smoking at Time 1 and parental smoking at Time 2 in the path from parenting to past-30-day smoking.

4.3. Mediation analyses

Because our SEM results suggested a significant path from a parent collectivistic values to youth smoking by way of familismo and parenting, we conducted mediation analyses to determine whether these mediated pathways were statistically significant. Similarly, because we observed a pathway leading from perceived discrimination to youth smoking by way of familism and parenting, we tested whether familism mediated the relationship between perceived discrimination and parenting and whether parenting mediated the relationship between familism and youth smoking. Our results indicated that familism mediated the effect of collectivist values on parenting (95% CI [.11, 0.34]) and between perceived discrimination and parenting (95% CI [−0.24, −0.00]). Parenting, in turn, mediated the relationship between familism and youth smoking (95% CI [−0.39, −0.03]; MacKinnon, 2008).

5. Discussion

The current study integrates theory and empirical research on acculturation, family, and youth well-being into a process-oriented model to better understand how Latina/o parents’ experiences with acculturation, perceived discrimination, and context of reception influence family processes to impact Latino/a youth risks for smoking and depression. This investigation is an important next step in research on Latino/a youth acculturation, smoking, and depression. Most prior studies have employed simplistic measures of acculturation and have focused on how youths’ own experiences with acculturation, perceived discrimination, and context of reception impact their own adjustment. However, family process theories suggest that parents’ acculturation and related stress may also influence youth smoking and depression risk through family processes (Gerdes & Lawton, 2014; Santisteban et al., 2012). To investigate this possibility, we proposed and tested a process-oriented model through which recent immigrant parents’ cultural experiences (acculturative processes, perceived discrimination, and context of reception) influenced youth smoking and depressive symptoms by way of family processes (family values and parenting). Understanding how parents’ experiences influence youth smoking and depressive symptoms provides a richer understanding of the acculturation process and can inform tailored programs aimed at reducing smoking and depression risk in Latino/a youth.

5.1. Key findings and implications

Results indicated two pathways by which parent acculturation domains and experiences with perceived discrimination impacted youth smoking. As hypothesized, parent-reported collectivistic values predicted more parent-reported familism, which predicted more positive/involved parenting (which then negatively predicted youth smoking). Additionally and as expected, parent-reported perceived discrimination predicted less parent-reported familism, and this lowered familism predicted less positive/involved parenting, which in turn predicted greater likelihood of youth smoking. This pattern of findings suggests that parent-reported collectivistic values may facilitate familism, thereby promoting more positive/involved parenting and protecting youth from smoking. Moreover, findings suggest that parent-reported perceived discrimination was linked with lower familism, thereby increasing smoking risk in youth by way of parenting. Together, these findings highlight the necessity of prevention programs that target both the family (collectivistic values, familism, and parenting) and the community (discrimination).

The finding that collectivistic values may protect youth from smoking (by way of familism and parenting) parallels prior studies that found that collectivistic values may protect immigrant Latino/a college students from risk-taking (Schwartz et al., 2011) and Latino/a immigrant youth from alcohol use (Lorenzo-Blanco et al., in press) and intentions to smoke (Lorenzo-Blanco et al., 2015). The present investigation contributes to this line of research by indicating how parent-reported collectivistic values nurture family values, which in turn promote positive parenting, thereby protecting youth from smoking. Prior research with Latino/a youth has documented the protective role of youth-reported familism on youth mental health and substance use (e.g., Gil et al., 2000; Lorenzo-Blanco et al., 2012). The current study adds to this line of inquiry by showing how parent-reported familism predicts lower youth smoking risk.

Perceived discrimination was also associated with lower familism. This finding supports previous research indicating a negative association between socio-cultural stress and familism in youth (Gil et al., 2000). The present investigation generalizes this finding to parents as well. It is possible that daily experiences of unfair, differential treatment leads to chronic stress that may take a toll on parents’ well-being, making it more difficult for parents to engage in involved/positive parenting (Conger et al., 2010).

Surprisingly, positive/involved parenting did not relate to adolescent depressive symptoms. This finding suggests that the process from parent acculturation and parent socio-cultural stress to youth outcomes may depend on the outcome under investigation. With regard to the present study, our findings suggest that the pathway from parent acculturation, parent perceived discrimination, and parent negative context of reception to youth depressive symptoms may differ from the pathway through which parent-reported experiences may influence cigarette smoking. Thus, future research could benefit from a more in-depth investigation regarding which specific parent-reported experiences influence youth depressive symptoms. Additionally, it is possible that the relationship between parenting and depressive symptoms may depend on the gender of the primary caregiver (i.e., mothers versus fathers; White, Liu, Nair, & Tein, 2015), and future research could benefit from investigating the moderating role of parent gender in the effect of parents’ cultural experiences in family processes and in youth symptoms of depression.

Interestingly, in the present study, youth gender was not correlated with symptoms of depression. This finding is surprising because extant research with second and later generation U.S. Latina/o youth indicates that Latina girls report more symptoms of depression than boys (CDC, 2014; Lorenzo-Blanco et al., 2011, 2012). It is possible that gender differences in depressive symptomatology may emerge as Latina/o youth in the current study spend more time in the U.S., raising interesting and important questions about acculturation and gender related differences in depressive symptomatology among recent immigrant Latina/o youth.

Importantly, our findings can inform preventive interventions to reduce cigarette smoking among Latino/a youth. Parent-reported collectivistic values were linked with parent-reported familism, which in turn was linked with more involved/positive parenting. Positive parenting, in turn, was related to less cigarette use. Thus, programs aimed at reducing and preventing cigarette use among Latino/a youth may target family processes (familism and parenting). Such efforts would be consistent with culturally adapted parent management training (PTM) (Martínez and Eddy, 2005). Additionally, PTM could be extended by helping Latina/o parents find ways to cope with experiences of perceived discrimination in ways that do not compromise their family relationships (Santisteban et al., 2013). In addition to parent-focused interventions, macro-systemic efforts are needed to reduce discrimination against Latina/os, which could be implemented in community settings such as work-places and schools (Moradi & Risco, 2006).

5.2. Limitations

Although the present study makes important contributions to the literature, our findings should be interpreted in light of several important limitations. First, a majority of participating parents and youth in Miami were Cuban (61%), and the majority of participants in Los Angeles were Mexican (70%). Much smaller numbers of other Latino/a subgroups were represented in the current study, and it is not clear how findings from the current study reflect the experiences of other Latino/a subgroups (e.g., Puerto Ricans, Guatemalans). It is important for future studies to recruit more heterogeneous samples with regard to Latino/a ancestry. Second, both Miami and Los Angeles are relatively large and well-established receiving communities for Latina/o immigrants with many ethnic enclave neighborhoods that may minimize negative context of reception and limit experiences of discrimination. Findings from this investigation may not reflect the experiences of parents and children who migrate into new settlement communities (e.g., the Midwest and Deep South) that have less experience interacting with newcomers (Barrington, Messias, & Weber, 2012). Therefore, future studies should aim at replicating the current study with Latino/a immigrant families in less established but growing settlement communities (Rodríguez, 2012). Moreover, youth were asked to self-report their smoking and symptoms of depression. Although self-report and objective indicators of substance use tend to converge well in Latino/a adolescents (Dillon, Turner, Robbins, & Szapocznik, 2005), future studies should collect data from additional informants such as parents and teachers.

6. Conclusion

The present study offers several important contributions to the literature. First, our focus on parent acculturation and parent socio-cultural stress has allowed us to gain a more nuanced and richer understanding of the acculturation process, and the ways in which it can influence family processes and ultimately youth smoking and depressive symptoms. Second, the use of a bi-dimensional/multi-domain model of acculturation has allowed us to identify the specific acculturation domains that predict family processes and youth smoking and depressive symptoms. Specifically, our data indicate that parent collectivistic values may protect Latina/o youth from smoking, whereas parent discrimination may increase youth smoking risk. Results from this study highlight the need for youth preventive interventions to not only target parents’ cultural experiences in the family (collectivistic values, familism values, and parenting) but also to attend to parents’ experiences with discrimination.

Acknowledgements

Preparation of this article was supported by Grant DA025694 (National Institute of Drug Abuse and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; Seth J. Schwartz and Jennifer B. Unger, PI’s).

References

- Anderson JC, & Gerbing DW (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: a review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103, 411–423. 10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Asparouhov T, & Muthen B. (2010). Weighted least squares estimation with missing data.. Retrieved May 31, 2012 from. http://www.statmodel.com/download/GstrucMissingRevision.pdf

- Azen R, & Walker CM (2011). Categorical data analysis for the behavioral and social sciences. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Barrington C, Messias DKH, & Weber L. (2012). Implications of racial and ethnic relations for health and well-being in new Latino communities: a case study of West Columbia, South Carolina. Latino Studies, 10, 155–178. 10.1057/lst.2012.5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann AA, Kuhlberg JA, & Zayas LH (2010). Familism, mother-daughter mutuality, and suicide attempts of adolescent Latinas. Journal of Family Psychology, 24, 616–624. 10.1037/a0020584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beal SJ, Negriff S, Dorn LD, Pabst S, & Schulenberg J. (2014). Longitudinal associations between smoking and depressive symptoms among adolescent girls. Prevention Science, 15, 506–515. 10.1007/s11121-013-0402-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW (1997). Immigration, acculturation, and adaptation. Applied Psychology, 46, 5–34. 10.1111/j.1464-0597.1997.tb01087.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt H, & Lopez SR (1993). The study of culture, ethnicity, and race in American psychology. American Psychologist, 48, 629–637. 10.1037/0003-066X.48.6.629 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cano MÁ, Schwartz SJ, Castillo LG, Romero AJ, Huang S, Lorenzo-Blanco EI, et al. (2015). Depressive symptoms and externalizing behaviors among Hispanic immigrant adolescents: examining longitudinal effects of cultural stress. Journal of Adolescence, 42, 31–39. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.03.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2014) [Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance—United States, 2013]. MMWR; 61 (No. 4). [Google Scholar]

- Coleman JC (2011). The nature of adolescence (4th ed.). New York, NY: Routlege. [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Conger KJ, & Martin MJ (2010). Socioeconomic status, family processes: and individual development. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72, 685–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crockett LJ, Randall BA, Shen Y, Russell ST, & Driscoll AK (2005). Measurement equivalence of the center for epidemiological studies depression scale for Latino and Anglo adolescents: a national study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73, 47–58. 10.1037/0022-006X.73.1.47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon FR, Turner CW, Robbins MS, & Szapocznik J. (2005). Concordance among biological, interview, and self-report measures of drug use among African American and Hispanic adolescents referred for drug abuse treatment. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 19, 404–413. 10.1037/0893-164X.19.4.404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein JA, Botvin GJ, & Diaz T. (1998). Linguistic acculturation and gender effects on smoking among Hispanic youth. Preventive Medicine: An International Journal Devoted to Practice and Theory, 27, 583–589. 10.1006/pmed.1998.0329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falicov CJ (2014). Latino families in therapy (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gil AG, Wagner EF, & Vega WA (2000). Acculturation, familism and alcohol use among Latino adolescent males: longitudinal relations. Journal of Community Psychology, 28, 443–458. 10.1002/1520-6629(200007) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman-Smith D, Tolan PH, Zelli A, & Huesmann LR (1996). The relation of family functioning to violence among inner-city minority youths. Journal of Family Psychology, 10, 115–129. 10.1037/0893-3200.10.2.115 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X, Suarez-Morales L, Schwartz SJ, & Szapocznik J. (2009). Some evidence for multidimensional biculturalism: confirmatory factor analysis and measurement invariance analysis on the Bicultural Involvement Questionnaire—short version. Psychological Assessment, 21, 22–31. 10.1037/a0014495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho J. (2010). Acculturation gaps in Vietnamese immigrant families: impact on family relationships. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 34, 22–33. 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2009.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, & Bentler PM (1998). Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods, 3, 424–453. 10.1037/1082-989X.3.4.424 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. (2012). IBM SPSS statistics for windows, Version 21.0. Armonk, NY: IBM. [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Neale MC, MacLean CJ, Heath AC, Eaves LJ, & Kessler RC (1993). Smoking and major depression. A causal analysis. Archives of General Psychiatry, 50, 36–43. 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820130038007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerdes AC, & Lawton KE (2014). Acculturation and Latino adolescent mental health: integration of individual environmental, and family influences. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 17, 385–398. 10.1007/s10567-014-0168-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little TD, Rhemtulla M, Gibson K, & Schoemann AM (2013). Why the items versus parcels controversy needn’t be one. Psychological Methods, 18, 285–300. 10.1037/a0033266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo-Blanco EI, & Cortina LM (2013). Towards an integrated understanding of Latino/a acculturation, depression, and smoking: a gendered analysis. Journal of Latina/o Psychology, 1, 3–20. 10.1037/a0030951 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Zamboanga BL, Des Rosiers SE, Huang S, et al. (2015). Latino/a youth intentions to smoke cigarettes: exploring the roles of culture and gender. Journal of Latina/o Psychology, 3, 129–142. 10.1037/lat0000034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Zamboanga BL, Des Rosiers SE, Villamar JA, et al. (in press). Alcohol use among recent immigrant Latino/a youth: acculturation, gender, and the theory of reasoned action. Ethnicity and Health. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Unger JB, Ritt-Olson A, Soto D, & Baezconde-Garbanati L. (2011). Acculturation, gender, depression, and cigarette smoking among U.S. Hispanic youth: the mediating role of perceived discrimination. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40, 1519–1533. 10.1007/s10964-011-9633-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Unger JB, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Ritt-Olson A, & Soto D. (2012). Acculturation, enculturation, and symptoms of depression in Hispanic youth: the roles of gender, Hispanic cultural values, and family functioning. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 41, 1350–1365. 10.1007/s10964-012-9774-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lueck K, & Wilson M. (2011). Acculturative stress in Latino immigrants: the impact of social, socio-psychological and migration-related factors. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 35, 186–195. 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2010.11.016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP (2008). Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez CR Jr., & Eddy JM (2005). Effects of culturally adapted parent management training on Latino youth behavioral outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73, 841–851. 10.1037/0022-006X.73.5.841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maslowsky J, & Schulenberg JE (2013). Interaction matters: quantifying conduct problem depressive symptoms interaction and its association with adolescent alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use in a national sample. Development and Psychopathology, 25, 1029–1043. 10.1017/S0954579413000357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda AO, Estrada D, & Firpo-Jimenez M. (2000). Differences in family cohesion, adaptability, and environment among Latino families in dissimilar stages of acculturation. The Family Journal, 8, 341–350. 10.1177/1066480700084003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moradi B, & Risco C. (2006). Perceived discrimination experiences and mental health of Latina/o American persons. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53, 411–421. 10.1037/0022-0167.53.4.411 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (1998–2012). Mplus user’s guide (7th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén Copyright. [Google Scholar]

- Ogbu JU (1994). From cultural differences to differences in cultural frame of reference. In Greenfield PM, & Cocking PR (Eds.), Cross-cultural roots of minority child development (pp. 365–391). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez DJ, Fortuna L, & Alegría M. (2008). Prevalence and correlates of everyday discrimination among U.S. Latinos. Journal of Community Psychology, 36, 421–433. 10.1002/jcop.20221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padilla AM, & Perez W. (2003). Acculturation, social identity, and social cognition: a new perspective. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 25, 35–55. 10.1177/0739986303251694 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS, Madden T, & Santos LJ (1998). Psychological variables as predictors of perceived ethnic discrimination among minority and immigrant adolescents1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 28, 937–953. 10.1111/j.1559-1816.1998.tb01661.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Portes A, & Rumbaut RG (2006). Immigrant America: a portrait (3rd ed.). Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt LA, & Brody DJ (2014). Depression in the U.S. household population, 2009–2012. NCHS data brief, no 172. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prokhorov AV, Winickoff JP, Ahluwalia JS, Ossip-Klein D, Tanski S, Lando HA, et al. (2006). Youth tobacco use: a global perspective for child health care clinicians. Pediatrics, 118, e890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quattrocki E, Baird A, & Yurgelun-Todd D. (2000). Biological aspects of the link between smoking and depression. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 8, 99–110. 10.1080/hrp8.3.99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS (1977). The CES-D scale a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401. 10.1177/014662167700100306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera FI, Guarnaccia PJ, Mulvaney-Day N, Lin JY, Torres M, & Alegría M. (2008). Family cohesion and its relationship to psychological distress among Latino groups. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 30, 357–378. 10.1177/0739986308318713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RE, Phinney JS, Masse LC, Chen Y, Roberts CR, & Romero A. (1999). The structure of ethnic identity of young adolescents from diverse ethnocultural groups. Journal of Early Adolescence, 19, 301–322. 10.1177/0272431699019003001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez N. (2012). New southern neighbors: latino immigration and prospects for intergroup relations between African-Americans and Latinos in the South. Latino Studies, 10, 18–40. 10.1057/lst.2012.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Romero AJ, & Ruiz M. (2007). Does familism lead to increased parental monitoring? Protective factors for coping with risky behaviors. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 16, 143–154. 10.1007/s10826-006-9074-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Santisteban DA, Coatsworth JD, Briones E, Kurtines W, & Szapocznik J. (2012). Beyond acculturation: an investigation of the relationship of familism and parenting to behavior problems in Hispanic youth. Family Process, 51, 470–482. 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2012.01414.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santisteban DA, Mena MP, & Abalo C. (2013). Bridging diversity and family systems: culturally informed and flexible family-based treatment for Hispanic adolescents. Couple and Family Psychology: Research and Practice, 2, 246–263. 10.1037/cfp0000013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santisteban DA, & Mitrani VB (2003). The influence of acculturation processes on the family. In Chun KM, Organista PB, & Marín G. (Eds.), Acculturation: advances in theory, measurement, and applied research (pp. 121–135). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Des Rosiers S, Huang S, Zamboanga BL, Unger JB, Knight GP, et al. (2013). Developmental trajectories of acculturation in Hispanic adolescents: associations with family functioning and adolescent risk behavior. Child Development, 84, 1355–1372. 10.1111/cdev.12047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Park IJK, Huynh Q-L, Zamboanga BL, Umanã-Taylor AJ, Lee RM, et al. (2012). The American Identity Measure: development and validation across ethnic subgroup and immigrant generation. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research, 12, 93–128. 10.1080/15283488.2012.668730 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Des Rosiers SE, Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Zamboanga BL, Huang S, et al. (2014). Domains of acculturation and their effects on substance use and sexual behavior in recent Hispanic immigrant adolescents. Prevention Science, 15(1–12) 10.1007/s11121-013-0419-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Des Rosiers SE, Villamar JA, Soto DW, et al. (2014). Perceived context of reception among recent Hispanic immigrants: conceptualization, instrument development, and preliminary validation. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 20, 1–15. 10.1037/a0033391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Zamboanga BL, & Szapocznik J. (2010). Rethinking the concept of acculturation: implications for theory and research.American Psychologist, 65, 237–251. 10.1037/a0019330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Weisskirch RS, Zamboanga BL, Castillo LG, Ham LS, Huynh QL, et al. (2011). Dimensions of acculturation: associations with health risk behaviors among college students from immigrant families. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 58, 27–41. 10.1037/a0021356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Zamboanga BL, Rodriguez L, & Wang SC (2007). The structure of cultural identity in an ethnically diverse sample of emerging adults. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 29, 159–173. 10.1080/01973530701332229 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steidel AGL, & Contreras JM (2003). A new familism scale for use with Latino populations. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 25, 312–330. 10.1177/0739986303256912 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tingvold L, Middelthon AL, Allen J, & Hauff E. (2012). Parents and children only? Acculturation and the influence of extended family members among Vietnamese refugees. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 36, 260–270. 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2011.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tofighi D, & MacKinnon DP (2011). RMediation: an R package for mediation analysis confidence intervals. Behavior Research Methods, 43, 692–700. 10.3758/s13428-011-0076-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triandis HC, & Gelfand MJ (1998). Converging measurement of horizontal and vertical individualism and collectivism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 118–128. 10.1037/0022-3514.74.1.118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Turner CF, Ku L, Rogers SM, Lindberg LB, Pleck JH, & Sonsenstein LH (1998). Adolescent sexual behavior, drug use, and violence: Increased reporting with computer survey technology. Science, 5365, 867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2014). Let’s make the next generation tobacco-free. Your guide to the 50th anniversary Surgeon’s General’s report on smoking and health. [Google Scholar]

- Van Campen KS, & Romero AJ (2012). How are self-efficacy and family involvement associated with less sexual risk taking among ethnic minority adolescents? Family Relations, 61(4), 548–558. 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2012.00721.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weersing RV, & Brent DA (2006). Cognitive behavioral therapy for depression in youth. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 15, 939–957. 10.1016/j.chc.2006.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White R, Liu Y, Nair RL, & Tein JY (2015). Longitudinal and integrative tests of family stress model effects on Mexican origin adolescents. Developmental Psychology, 51, 649–662. 10.1037/a0038993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]