Abstract

The basic packaging unit of eukaryotic chromatin is the nucleosome that contains 145-147 base pair duplex DNA wrapped around an octameric histone protein. While DNA sequence plays a crucial role in controlling the positioning of the nucleosome, the molecular details behind the interplay between DNA sequence and nucleosome dynamics remains relatively unexplored. This study analyzes this interplay in detail by performing all-atom molecular dynamics simulations of nucleosomes, comparing the human α-satellite palindromic (ASP) and the strong positioning ‘Widom-601’ DNA sequence at timescales of 12 microseconds. The simulations are performed at salt concentrations 10-20 times higher than physiological salt concentrations to screen the electrostatic interactions and promote unwrapping. These microseconds-long simulations give insight into the molecular-level sequence-dependent events that dictate the pathway of DNA unwrapping. We find that the ‘ASP’ sequence forms a loop around SHL ± 5, for three sets of simulations. Coincident with loop formation is a cooperative increase in contacts with neighboring N-terminal H2B tail and C-terminal H2A tail and the release of neighboring counterions. We find that the ‘Widom-601’ sequence exhibits a strong breathing motion of the nucleic acid ends. Coincident to the breathing motion is the collapse of the full N-terminal H3 tail and formation of an α-helix that interacts with the H3 histone core. We postulate that the dynamics of these histone tails, and their modification with posttranslational modifications (PTMs), may play a key role in governing this dynamics.

Introduction

The nucleosome is the elementary building block of chromatin, a protein-DNA complex that packages the genome in the eukaryotic cell 1-4 The nucleosome core particle (NCP) consists of a 147 base pair duplex DNA wrapped ~1.7 times in a left-handed helical fashion around a positively charged octameric histone protein core 5, 6. This octameric histone protein complex is formed by two copies of four histone subunits, H2A, H2B, H3, and H4. Each of these histone subunits has a highly ordered helical globular core region surrounded by disordered flexible positively charged tails that play a crucial role in modulating the biological activity of the nucleosome 3, 4 The nucleosome represents 75-90% of the whole genome. Thus, understanding the molecular level factors that govern the positioning of the nucleosome and their dynamics is an essential step towards a broader understanding of genomic processes.

The tight histone-DNA binding interface in the nucleosome occludes DNA access by transcription factors or other DNA binding proteins 7. The positioning of the nucleosome shifts with time, allowing DNA access during genomic processes 8, 9. Such a shifting of nucleosome positioning is achieved by nucleosome sliding/repositioning, where the DNA slides along the histone surface without disrupting the overall structure, resulting in the translocation of DNA base pairs. This process can occur spontaneously or through an active chromatin remodeler, which uses ATP energy to displace the DNA 10. There are two different mechanisms for DNA repositioning. The first mechanism is "loop propagation" (propagation of a loop leading to the shifting of approximately ten base pairs outwards away from the histone) 11-16, and the second mechanism is "twist-diffusion" (propagation of a twist-defect leading to one base pair shifting) 17-20. Several single-molecule experiments have reported repositioning mechanisms that suggest twist diffusion21-23. Both mechanisms are supported by some experimental evidence13, 16, 21-23. Several single-molecule experiments have reported repositioning mechanisms that do not follow either of these models24, 25. This suggests that nucleosome repositioning depends on several factors, including the underlying DNA sequence 26. However, unlike the role of sequence in governing nucleosome positioning, the role of DNA sequence on nucleosome dynamics remains unclear. Thus, a complete molecular-level understanding of sequence-dependent nucleosome dynamics must be developed.

The timescales associated with nucleosome unwrapping range from microseconds to seconds. Small-scale rearrangements such as breathing, and loop formation occur at microsecond time scales 27-29. Large-scale rearrangements, such as unwrapping, range from milliseconds to seconds 30, 31. Complete repositioning occurs over minutes to hours 32-34. This wide range of timescales suggests that a single experimental technique will not be sufficient to understand the nucleosome dynamics completely. Therefore, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations can be an attractive alternative to interpret the experimental results by elucidating molecular details. MD simulations have been used to unravel several aspects of the nucleosome, such as the role of counterions and hydration patterns around the nucleosome 35, nucleosome dynamics 36-40, the role of the histone tails 27, 41, 42, etc. However, the timescales of these simulation studies were limited to timescales of microseconds or less. Multiple simulation studies are available now in the literature, where the simulations were performed for several microsecond timescales with complete atomistic details 43-45. To explore higher-order organization such as tetra-nucleosome folding, free energy methods are required 46. Asymmetric motions of the breathing motions of the DNA tails have been shown to be salt dependent40 due to specific interactions of the H2A tails with neighboring DNA. Here we highlight and compare further simulation results at ion concentrations 10-20 times larger than physiological ion concentration to long-time simulations by Armeev et al. 44 who observed DNA sliding which was mediated by twist-defects 47, which were performed at physiological ion concentrations. We did not specifically quantify the formation of twist defects. However, we did observe differences (and significant peaks) in dinucleotide base pair parameters, such as twist, that could facilitate the formation of such defects. Dinucleotide base pair parameters are dependent on the definition of each base pair as a plane. Thus, the beginnings of a twist defect might be correlated to peaks in the deformation energy from the dinucleotide base-pair parameters. Notably, we have included the full H3-N terminal tails, as opposed to the truncated tails in Armeev et al., for the ‘Widom-601’ NCP. Other sequence-dependent simulation studies available so far have primarily used coarse-grained models of the nucleosome, including implicit solvent models 48, 49. For example, de Pablo's group developed a coarse-grained model for the nucleosome that was shown to capture sequence-dependent dynamics of nucleosome 48. Using their coarse-grained model, they could show that nucleosome repositioning occurs either by "loop propagation" or "twist-diffusion.". Takada's group later used de Pablo's coarse-grained model to investigate multiple aspects of the sequence-dependent repositioning dynamics 49-51

Herein we perform all-atomistic explicit solvent simulations at 12 μs timescales of the nucleosome core particle with two widely studied DNA sequences: the human a satellite palindromic (ASP) sequence and the strongly positioning ‘Widom-601’ sequence. We perform these simulations at salt concentrations 10-20 times higher than physiological ion concentrations to screen electrostatic interactions and to increase the sampling of intermediate states between the open and closed conformations. Here, we provide these simulations as further evidence that the nucleosome dynamics are sequence-dependent, and we suggest a mechanism for the dynamics on the base-pair level using calculation of the elastic deformation of the DNA based on dinucleotide deformation variables, a pioneering approach developed by Olson et al.52 Using this approach to characterize the deformability of a set of protein-DNA crystal structures pyrimidine-purine dimers were suggested to act as flexible hinges.52 The present study suggests that the deformations in shift and roll for the pyrimidine-pyrimidine or purine-purine dinucleotide base steps present at specific super helical locations could be a key descriptor governing the nucleosome dynamics. The force field and salt concentration may play a role in regulating the range of elastic deformation energy, and further investigations of more sequences are necessary.

Methods

Force Field Parameters

The histone proteins were parameterized using ff19SB 53, while we used OL15 54 to model DNA. We used the OPC model for water 55. Na+ and Cl− were parameterized using Joung and Cheetham parameters (2008) 56, while Li/Merz compromised parameter set was used for Mg2+ ions 57. The Lennard-Jones interaction of Na+/OPC (OW) following Kulkarni et al. that estimates osmotic pressure better was used 58.

Simulation Protocols

Using Amber18 59, two systems were simulated in the NPT ensemble with Langevin dynamics 60, 61 with a temperature of 310 K. Details of the initial conformations for the two systems considered in this study (ASP and ‘601’) are described in SI Appendix. They were equilibrated for 100 ns with the DNA being constrained with a force constant of 10 kcal/mol/Å2. A damping coefficient of γ =1 ps−1, at a pressure of 1 atm, was used with a piston period of 100 fs and a damping time scale of 50 fs. The SHAKE algorithm 62 was used to fix hydrogen atoms allowing a two fs timestep. The Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) algorithm 63 was utilized to take total electrostatic interactions into account, with full periodic boundary conditions. The cut-off for van der Waals interactions was 12 Å with a smooth switching function at 10 Å. Bonded atoms were excluded from non-bonded atom interactions using a scaled 1-4 value. The Gaussian Split Ewald method 64 was used to accelerate the electrostatic calculations. The final production runs were carried out for 12 μs on Anton2 65.

Results

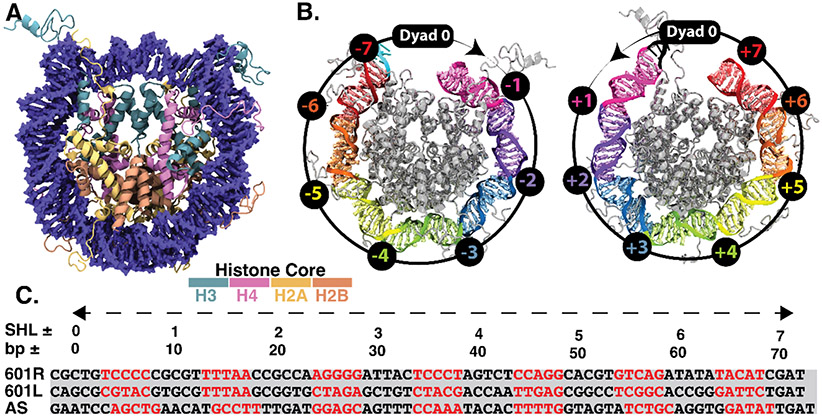

First, we describe the general terminology often used for characterizing the nucleosome core particle (see Fig. 1A for the crystal structure of nucleosome). The rotational orientation of the DNA base pairs of a nucleosome is commonly represented relative to the central base pair called superhelical location zero (SHL0), where each SHL consists of approximately ten bp (Fig. 1B). The minor groove sequence appears at a half-integer SHL location, which represents a total of 14 DNA-histone binding sites. These binding sites commonly involve kinking, often facilitated by flexible TA or CA=TG dinucleotide steps. The curvature at the minor grooves is thus significantly different from the curvature in the major grooves 32, 66, 67. Furthermore, the extent of bending among these 14 binding sites is also non-uniform, with a maximum curvature at SHL ± 1.5 and SHL ± 4-5 6. While all these 14 binding sites play a significant role in sequence-dependent nucleosome positioning, the relative degree of contribution differs among the sites, with a disproportionate contribution from SHL ± 1.5 33, 34. Variation of DNA sequence at this location significantly impacts the histone-DNA binding and hence the overall nucleosome positioning affinity. For example, TTTAA is known to increase the nucleosome positioning affinity when at this site. In this study, we analyze the ‘Widom-601’ sequence from 12 μs long equilibrium atomistic simulations and compare the results with the same length simulation with the ASP sequence (see the complete sequence in Fig. 1C and SI Appendix for sequence comparison), characterizing the conformational flexibility of the DNA and the neighboring histone tails.

Fig. 1.

(A) Crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle. Histone subunits H2A, H2B, H3, and H4, are represented in four distinct colors with DNA in blue. (B) Left and right DNA halves of the nucleosome core particle. Various DNA turns are highlighted in distinct colors, while the histone octamer is represented in gray color. The rotational orientation of each turn corresponding to the DNA double helix is represented relative to the central base pair (super helix location zero, SHL-0, where the major groove faces the histone octamer) following the standard SHL notation, where the negative and positive values correspond to right and left halves, respectively. These SHL locations are marked on a representative circle with an arrow pointing from the histone core. (C) Comparison of DNA sequence for the crystal structure of nucleosome structure used in this study, 'Widom-601' and human α-satellite sequence (ASP). The red DNA sequence represents minor grooves, while black indicates the major grooves. Only one-half of the sequence is shown for the human α-satellite sequence as it is a palindromic sequence, whereas both right (601R) and left (601L) half sequence for the 'Widom-601' sequence are shown.

Conformational Dynamics of the Nucleosomal DNA

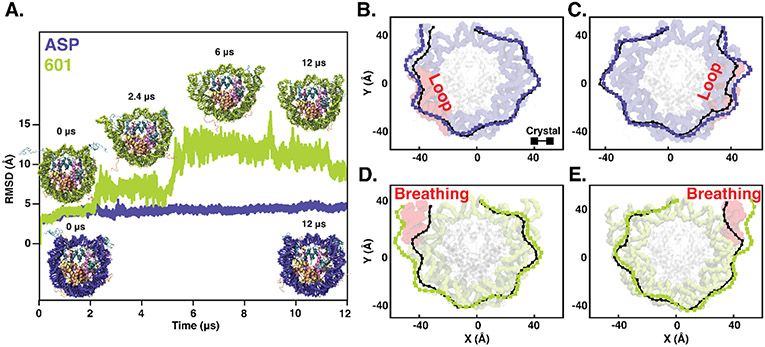

The two sequences display differing conformational dynamics as shown in Fig. 2. The ASP sequence forms a large loop in the DNA in the SHL +5 region bp ± (45-55), consistent with earlier reported studies27, 43, 67. (Fig. 2 B, C). We find that the ‘Widom-601’ sequence exhibits large breathing motions, with the left nucleosomal DNA end opening up, followed by the right end (Fig. 2 D, E). The root mean squared deviation (RMSD) of the DNA backbone (Fig. 2A) jumps at ~2 μs (left end opening) followed by another jump at ~5 μs (right end opening). There is a complete loss of native DNA-histone contacts in the SHL-6 to −7 and SHL +6 to +7 regions of the nucleosomal DNA with each jump (see SI Appendix, Figs. S1 A and B). We observe asymmetric DNA unwrapping consistent with earlier studies 30, 31, 39, 40, 68 and supported by the time variation of twist angle (SI Appendix, Figs. S1 C and D). To quantify the loop/bulge forming tendency, we have also calculated the loop/bulge forming probability for each of the residues (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). Here, the loops are defined when the difference of the order parameter R in the simulated structure and crystal structure is more than 2 Å but lesser than 6 Å. R is each base pair's average distance (R) over relative to the center of mass of DNA non-hydrogen atoms in the crystal structure. Results suggest that both the sequences tend to form loop/bulge at SHL ± 5, but the tendency is higher for ASP (more than 80%) than the 'Widom-601' sequence.

Fig. 2.

(A) Time evolution of root mean square deviation (RMSD) of DNA non-hydrogen atoms for the nucleosome with human α-satellite (ASP, shown in blue) and 'Widom-601' sequence (shown in green). The representative structures corresponding to the sharp changes associated with RMSD values and the structures at the beginning and end of 12 μs simulations are highlighted. Two-dimensional projection of DNA for (B-C) the human α-satellite sequence (ASP, shown in blue) and (D-E) for the 'Widom-601' sequence (shown in green) as obtained at the end of 12 μs simulations. For comparison, a similar projection for the respective crystal structure is shown in black. The corresponding simulated configurations are also shown in each panel B-E to highlight the regions with a loop or breathing (shown in red). Two DNA halves, left (SHL-0 to SHL-7, panels B and D) and right (SHL-0 to SHL+7, panels C and E), are shown separately.

Characterization of Loop/Bulge

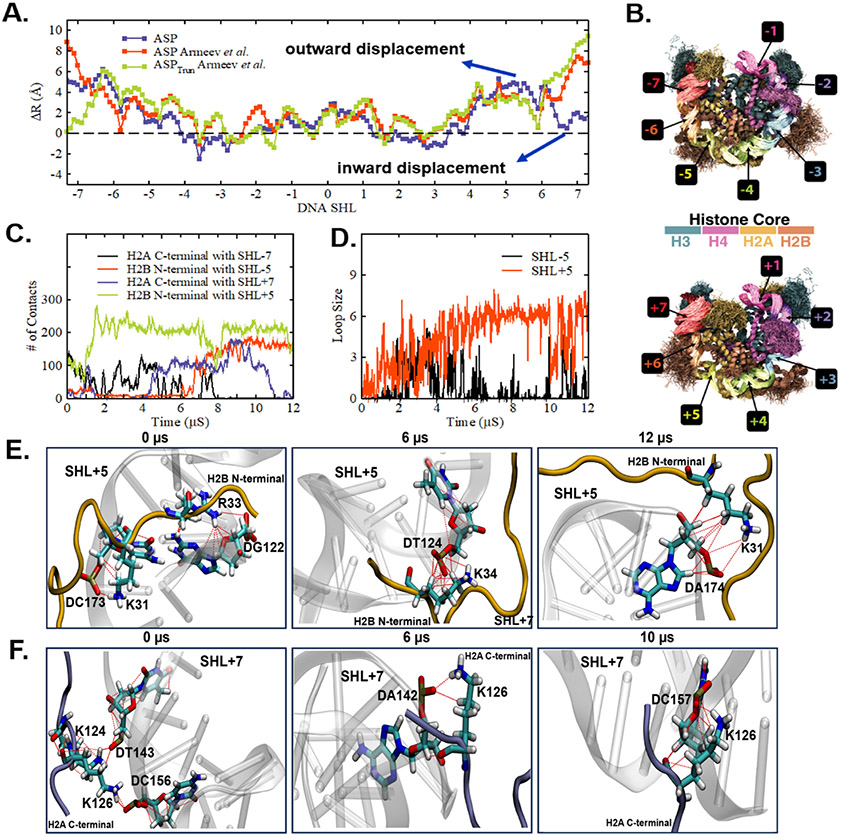

We characterize the final configuration of the DNA at the end of the simulation trajectories by calculating displacement of the center of the mass of each base pair relative to the crystal structure over the last 1 μs simulations. Fig. 3A suggests that simultaneous inward and outward displacement of consecutive DNA regions-–a “wave-like motion”— drives the formation of a loop in SHL + 5 of the ASP sequence. We previously showed such a wave-like motion to drive the formation of loop/bulge 43. However, the SHL locations for such an inward and outward displacement were observed in the opposite direction (SI Appendix, Fig. S4A). Next, we compare with previous trajectories of Armeev et al.69, for which the parmbc0 force field70 was used to model DNA at physiological ion concentration. We note that a loop forms in SHL + 5 for both Armeev et al. simulations, with both full and truncated histone tails (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). Our current trajectories use the OL15 nucleic acid force field which improves the sugar-phosphate backbone torsions71 (see SI Appendix, Fig. S6 for the 2-dimensional projection of the nucleosome simulated with OL15 force field). Differences in both the structure of the nucleic acid (major and minor groove width) as well as the sequence-dependent elasticity have been found between the CHARMM and parmbc0 force fields70. Regardless, for all sets of force fields and salt concentrations, for the ASP sequence, a loop is observed in the SHL + 5 regions, indicating a behavior independent of force field and laboratory.

Fig. 3.

(A) Average distance (R) of each DNA base pair center (represented in SHL notation) with respect to the center of mass of non-hydrogen atoms of DNA in the crystal structure as obtained over the last 1 μs simulations of ASP sequence presented as the difference (ΔR) between the simulated and crystal structure. Simultaneous inward and outward displacement of DNA at SHL+6 and SHL+5 suggest a “wave-like” motion. Comparison with last 1 μs of trajectories from Armeev et al. (B) Superimposed simulated configurations of ASP sequence by highlighting various DNA SHL regions and histone proteins in distinct colors. For easy visualization, the superimposed configurations are presented separately for left (SHL0 to SHL-7; top panel) and right (SHL0 to SHL+7; bottom panel) DNA halves. (C) The number of contacts between the H2A C-terminal/H2B N-terminal tail with SHL±7/SHL±5 as a function of time for the ASP sequence. (D) The loop size formed at SHL-5 and SHL+5 locations for ASP sequence as a function of time. (E) H2B N-terminal tail at 0 μs, 6 μs, and 12 μs forms a hydrogen bond between LYS/ARG with SHL+5 region of DNA. At 0 μs, there is a hydrogen bond between LYS31 and ARG33 with the phosphate backbone of DC173 and DG122. At 6 μs and 12 μs, there is a hydrogen bond between LYS34 and LYS31 with the phosphate backbone of DT124 and DA174 respectively. (F) H2A C-terminal tail at 0 μs, 6 μs, and 10 μs exhibits hydrogen bond between positively charged residues LYS/ARG with SHL+7 region of DNA. At 0 μs, it shows hydrogen bond of LYS124 and LYS126 with the phosphate backbone of DT143 and DC156. Similarly at 6 μs and 10 μs, it shows hydrogen bond of LYS126 with the phosphate backbone of DA142 and DC157.

Next, we focus on the path for the breathing of the ‘Widom-601’ sequences (see SI Appendix Fig. S7 and S8 and the discussion). The DR value greater than 10 Å in SHL ± 7 regions indicates significant breathing motion for the ‘Widom-601’ sequence for the present simulations with the OL15 force field (SI Appendix, Fig. S4B). We compare these results with that observed by Armeev et al. for the Widom-601 sequence with truncated tails (Fig. S8). In both backbone traces, there is a loop/bulge at SHL −6 that occurs prior to breathing. An independent simulation of the ‘Widom-601’ system with the CHARMM force field instead of the OL15 force field by our laboratory where we performed 20 μs long equilibrium atomistic simulations (SI Appendix, Fig. S4C) show the beginnings of a loop at SHL −6. Since the DNA end breathing, in this case, is almost negligible, we see a small loop/bulge with loop size ~2-3 at SHL ± 6. We note that loop/bulge formation at SHL ± 6 might be the first essential step for breathing to occur at end regions that essentially results in the unwrapping of the DNA from the histone core. We note that further investigation is required to verify the consistency of this observed force field dependence.

Now we focus on understanding the molecular mechanism behind loop formation. Histone tails are known to play a critical role in controlling nucleosome dynamics 27, 43. Here, we explore the role of histone tails in loop formation at SHL ± 5. The superimposed simulated nucleosome conformations shown in Fig. 3B indicate that the H2A C-terminal tail and H2B N-terminal tail condense on SHL ± 7 and SHL ± 5, respectively. Such condensation of the histone tail is coincident with the bound DNA bps to move either towards the histone protein complex or away from the complex depending on whether the histone tail condenses on the DNA surface from the inward face (inward DNA movement) or the outer face (outward DNA movement). We find that counterion release entropically favors this DNA-histone condensation and the consequent DNA movement (SI Appendix, Fig. S9). The H2A C-terminal tail condenses facilitating the inward movement of SHL ± 7, whereas the opposite is true for the H2B N-terminal tail (outward movement of SHL ± 5). The “wave-like” motion modulated by the H2A C-terminal tail and H2B N-terminal tail resulting in the formation of a loop, is consistent with our previous work 43. Next, we characterize the time evolution of H2A C-terminal/H2B N-terminal tail contacts with SHL ± 7/SHL ± 5 (Fig. 3C) and loop size of SHL ± 5 (Fig. 3D). A stable loop with more than five base pairs forms when the histone tails simultaneously make significant DNA-histone contacts. For instance, within the first ~5 μs for SHL-5, while the H2A C-terminal tail makes significant contact with SHL-7, the H2B N-terminal tail rarely condenses on SHL-5. Similarly, slightly later, although H2B N-terminal tail manages to form contact with SHL-5, the contacts between H2A C-terminal tail and SHL-7 disappear. On the other hand, a stable loop with more than size six pairs is formed at SHL+5, which remains after ~5 μs because both the histone tails simultaneously manage to establish stable DNA-histone contacts. The H2B N-terminal tail forms hydrogen bonds between LYS/ARG with the SHL+5 region of DNA (Fig. 5E). At the same time, the H2A C-terminal tail exhibits hydrogen bonds between positively charged residues LYS/ARG with the SHL+7 region of DNA. Both tails act cooperatively to form a stable loop.

Fig. 5.

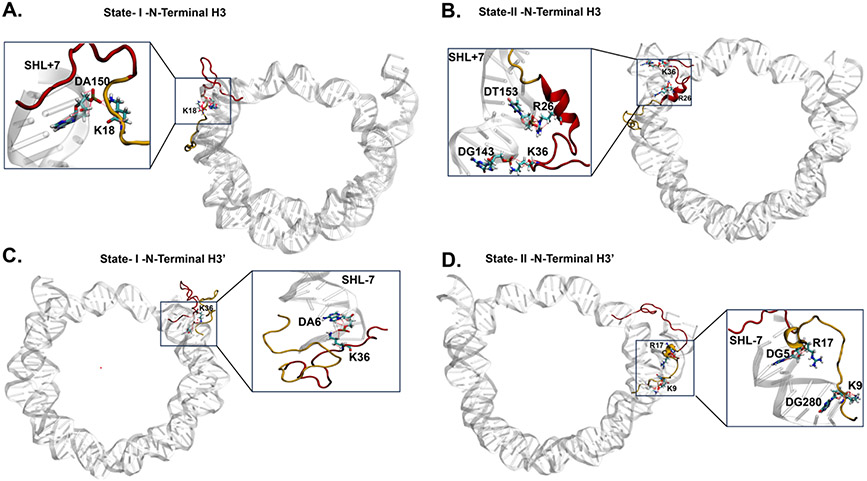

Conformations of the N-Terminal H3 tail extracted from the PCA free energy landscape as shown in Fig. 4 D I and II with neighboring DNA shows interaction between the SHL+7 base pairs and positively charged residues of the N-terminal H3 tail. (A) PCA conformation I of H3 N-terminal Tail 1 exhibits hydrogen bonds LYS18 and the phosphate backbone of DA150 of the SHL+7 region. (B) PCA conformation II of the H3 N-terminal Tail 1 exhibits hydrogen bonds of ARG26 and LYS36 with DT153 and DG143 of SHL+7, respectively. (C) PCA conformation I of the H3’ N-terminal Tail 2 shows hydrogen bond formation between LYS36 and DA6 of the SHL-7 region. (D) PCA conformation II of the H3’ N-terminal Tail 2 shows hydrogen bond formations between ARG17 and LYS9 with DG5 and DG280 of the SHL-7 region.

Breathing Motion of Nucleosomal DNA

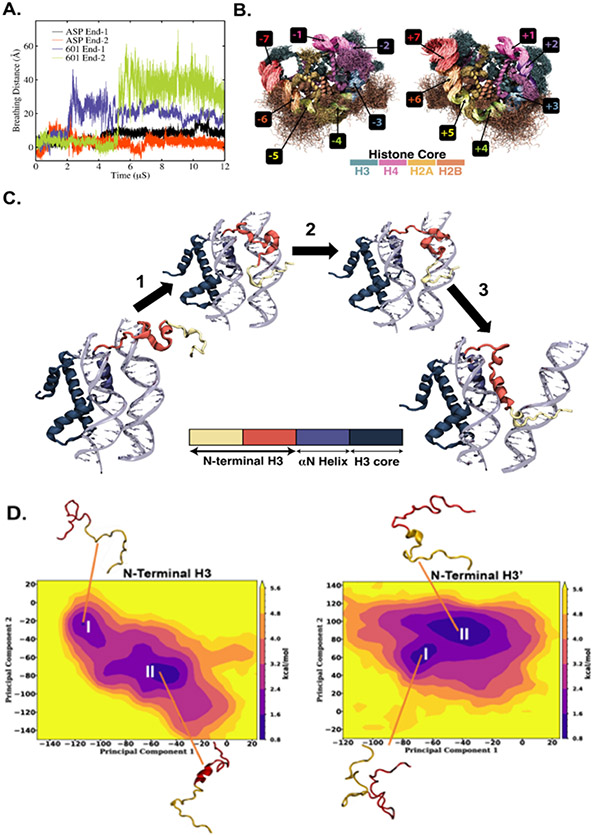

We next characterize the breathing motion of nucleosomal DNA. Breathing can occur in the DNA end regions due to the transient opening/closing of DNA entry/exit regions or between the inner gyres, where the two gyres come closer or move away from each other due to the modulation of histone-DNA contacts (SI Appendix, Fig. S10A). Here, we quantify the extent of End-breathing by computing the breathing distance in the simulated structure, defined as the distance between the center of mass of SHL0 bp and the terminal bp present at the entry/exit region. Fig. 4A displays the time evolution of breathing distance for both End-1 and End-2, represented as the difference with respect to the crystal structure. Breathing distance for both the DNA Ends of ASP system remains close to zero with negligible fluctuation, suggesting that the ASP sequence does not undergo breathing motion within our simulations. In contrast, frequent increase and decrease in the breathing distance, signifying unwrapping and rewrapping of DNA ends, respectively, indicates notable breathing motion for the DNA ends of the Widom-601 system. DNA ends exhibit breathing motion at different times (~2 μs onward for End-1 and ~6 μs onward for End-2). Interestingly, the degree of such a breathing motion for the two ends is different, illustrating that the breathing motion is asymmetric in nature. This is consistent with earlier simulations and experimental reports 30, 39, 40 We have also checked the inner-gyre breathing, by monitoring the time evolution of inner-gyre distance (see SI Appendix, Fig. S10B). Smaller but noticeable fluctuation after 6 μs in the inner-gyre distance for ‘Widom-601’ sequence is a signature of inner-gyre breathing motion. Further, for the ‘Widom-601’ sequence, we incidentally find that breathing between the gyres coincides when both DNA ends show breathing (Fig. 4A and SI Appendix, Fig. S10B). This may suggest that breathing of both the DNA ends is necessary for significant inner-gyre breathing.

Fig. 4.

(A) Time evolution of breathing distance for nucleosomal DNA End-1 and End-2 for both Widom-601 and ASP sequences. (B) Superimposed simulated configurations of Widom-601 sequence with highlighting various DNA SHL regions and histone proteins in distinct colors. For easy visualization, the superimposed configurations are presented for left (SHL0 to SHL-7; left panel) and right (SHL0 to SHL+7; right panel) DNA halves separately. (C) Mechanism for the role of H3 tail in governing the DNA end breathing. There are three major steps. Step 1: Condensation of extremely flexible H3 N-terminal tail (residues 1-15; shown in yellow) on the minor groove of SHL ± 6, Step 2: Condensation of H3 N-terminal residues 16 to 43 (shown in red) on SHL ± 7. This results in the movement of the DNA end region away from the histone core. Step 3: Helix-helix linkage formation between α-N core helix (blue) and N-terminal tail residues 16 to 43 (red) of H3 protein. This helix-helix linkage formation further leads to DNA outward movement, resulting in a notable breathing motion. D) PCA analysis was performed to study collective modes of the full H3 tails in the Widom-601 NCP over 12 μs. The free energy landscape constructed using the first two principal components for the H3 N-terminal Tail 1 (left) exhibits two major minima (I and II) corresponding to disordered and collapsed tail. For the H3’ N-terminal Tail 2 (right), the free energy landscape also exhibits to major minima (I and II).

Like loop formation, histone tails are expected to play a role in a breathing motion. We notice the H3 N-terminal tail is correlated with the DNA end breathing motion (Fig. 4B). We observe three major steps for DNA end breathing modulated by the H3 N-terminal tail, shown in Fig. 4C. At the first step, the flexible H3 N-terminal tail (residues 1-15) condenses in the minor groove near SHL ± 6 location (bp ± 57 to ± 62). In the second step, H3 N-terminal residues 16-43 condense on SHL ± 7. We found this second step to be entropically favored by counterion release (SI Appendix, Figure S10). Condensation occurs from the outer face and thus leads to outward movement of SHL ± 7 from the histone protein complex. This is when the DNA entry/exit region unwraps from the histone protein complex and initiates breathing motion. In the final step, a helix forms in H3 N-terminal tail residues 16-43. This helix is stabilized by a helix-helix linkage between this newly formed helix with the N-terminal helix in the H3 core region. This process is associated with a decrease in the number of contacts between SHL ± 7 and the H3 N-terminal tail residues 16-43 in the middle of the tail. A simultaneous decrease in DNA H3 N-terminal tail contacts and an increase in inter-helix contact between the H3 core and N-terminal tail results in the movement of SHL ± 7 further away from the histone surface. We observe this final step in the End-2 region but not in the End-1 region. This is correlated with the higher degree of breathing at End-2 than End-1 for the ‘Widom-601’ sequence. The above-described three-step mechanism for the breathing motion is also quantitatively confirmed by secondary structure and contact analysis (SI Appendix, Fig. S13). Here it may be noted that the contacts between SHL ± 6 and the H3 N-terminal remain intact throughout the trajectory. These contacts act as an anchor that restricts complete DNA unwrapping. Acetylation of the H3 N-terminal tail is known to speed up DNA unwrapping 72. Hence, the present study highlights the plausible molecular mechanism behind such an increase in unwrapping since acetylation is expected to weaken the condensation and decrease the energy barrier.

In contrast to the H3 N-terminal tail (Tail-1) residues 16-43, we did not observe the formation of a stable α-helix for the corresponding segment of H3' N-terminal tail (Tail-2). This lack of stability results from the frequent dynamic exchange between random and helical conformations, which slows down the final step. Consequently, we did not observe the final step for End-2, leading to a lower degree of breathing in this region. Our findings are supported by the presence of two states, I (random) and II (helical), as revealed by principal component analysis (PCA) of the H3/H3' N-terminal tail (Tail-1/Tail-2) in Figure 4D. We further demonstrate the frequent dynamic exchange between these two states for H3' N-terminal tail (Tail-2) and a clear separation between the states for the H3 N-terminal tail (Tail-1). This is shown through the time evolution of the two-dimensional free energy landscape projected onto the first two principal components (SI Appendix, Figure S11). Additionally, we discover that the two major states of H3/H3' N-terminal conformations are stabilized by specific hydrogen bonds formed between DNA base pairs at SHL ± 7 and Arg/Lys residues of the respective histone tail, as shown in Figure 5. This suggests that these favorable hydrogen bonding interactions serve as the underlying mechanism driving the condensation of H3/H3' tails on SHL ± 7. One of the Lysines, LYS9 interacts with DG280 of the SHL-7 region. LYS9 has been known to play a key role in gene expression via acetylation. H3 Lysine 9 acetylation (H3K9Ac) is a known epigenetic mark that represents transcription activation in chromatin. It has been shown that H3K9Ac can promote RNA Polymerase II pause release by serving as a substrate for the SEC (Super Elongation Complex) and promote transcription73. In addition, H3K9 methylation is known to recruit chromatin effector proteins involved in transcriptional silencing74. Like H3K9, H3K18Ac is known to be associated with transcription activation which is known to be acetylated via SAGA (Spt-Ada-Gcn5) acetyltransferase. The acetylation of H3 N-terminal tail can facilitate transcription by localizing the activators and by changing the nucleosome structure75.

Elastic Properties of Nucleosomal DNA

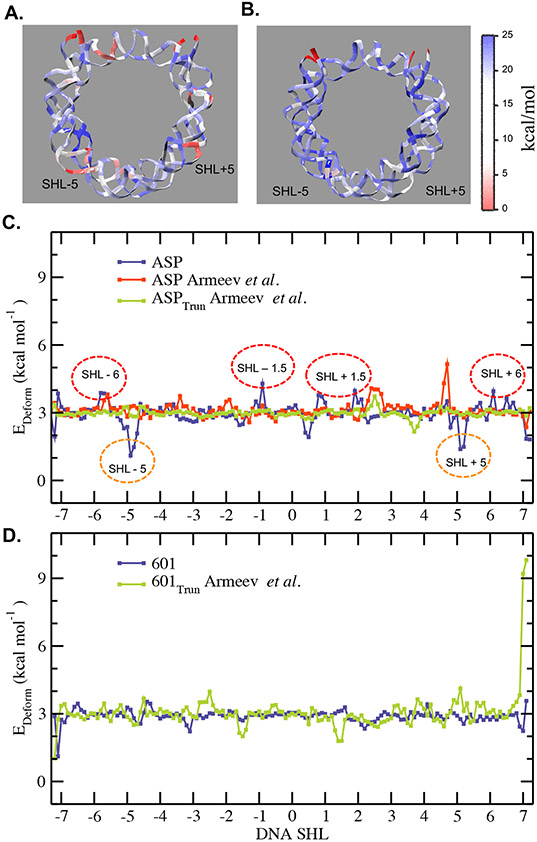

The unique ~1.7 superhelical turn of DNA around the nucleosome introduces significant deformation in its double helix structure, strikingly different from standard double-helix or that in a non-histone protein-DNA complex 18. We next correlate sequence-dependent conformational dynamics observed in the present study with the local elastic properties on the base pair level. We first calculate six deformation variables using Curves+ program 76. Using our in-house code, we then obtain the force constants associated with six dinucleotide helical deformation parameters (rise, shift, slide, twist, roll, and tilt) from the diagonal elements corresponding to the stiffness matrix (Figs. 5 A and B, SI Appendix, Figs. S16 and S17). Results show that bps near SHL ± 5 for the ASP sequence have relatively lower force constants than other regions, which is also lower than that in the ‘Widom-601’ sequence. Interestingly, we also observe comparatively low force constants in the end-regions (SHL ± 7) for the ‘Widom-601’ than that for the ASP sequence. The lower force constant, suggesting higher flexibility and consequently stronger DNA binding, seems contradictory to the observed loop formation at SHL ± 5 for ASP sequence and breathing motion at SHL ± 7 for ‘Widom-601’ sequence. However, this apparent contradiction is explained by the overall lower deformation energy cost (the product of DNA deformation and force constant; see Equation S2 in SI Appendix) in these regions due to lower force constants enabling higher deformation required for either breathing motion or loop formation. We will discuss this aspect quantitively in the subsequent sections. Importantly, this correlation between low force constants and loop formation at SHL ± 5 aligns well with our previous 5 μs atomistic simulations of the ASP sequence 43. Comparing the force constants of our trajectories with Armeev et. al, we further note that force constants follow similar trends (Figs. S20-22), with larger variations between the two 601 trajectories.

Next, we estimate the cost of deformation for each of the base pairs by calculating the deformation energy score (see SI Appendix for the definition). We restrict the calculations to those simulated configurations characterized by significantly large loop size (and volume) and degree of end breathing. For the ASP sequence, we consider the configurations that have a minimum loop size of 5 at both SHL ± 5, where a DNA bp is identified to form a loop if ΔR is at least 4 Å. We also check the deformation energy for both the ASP sequence with full histone tails and ASP sequence with truncated histone tails using other trajectories from Armeev et al. For both the ASP simulations from Armeev et al., we include those configurations where DNA bp is identified to form a loop if DR is at least 3 Å along with minimum loop size of 5. Similarly, a minimum breathing distance of 20 Å for both the DNA ends is used for the selection of the ‘Widom-601’ simulated configurations. For the trajectory of ‘Widom-601’ in Armeev et al. we use minimum breathing distance criteria as 10 Å for both the DNA ends. Fig. 6C displays the average deformation energy score as a function of bp shown in SHL notation. The results suggest that while bps near SHL ± 5 in the ASP sequence have a low deformation energy score, bps near SHL ± 6 require high deformation energies. This is consistent with “wave-like” motion associated with outward (low deformation) and inward displacements (more deformation) in the respective locations (see Fig. 3A). We note that deformation energies of our trajectory with the full histone tails using the OL15 DNA model exhibits larger deformations energies for the bps around the SHL +/− 1.5 regions, as compared with Armeev et al., which uses the parmbc0 force field for DNA. However, the peak in deformation for Armeev et al. trajectories shifts to the SHL +2.5 region. In our trajectories (10-20 times higher than physiological salt concentration), there is a minimum deformation energy around SHL+/−5 that is not seen in Armeev et al. This is indeed because we find a loop that forms in the SHL +/−5 region. On the other hand, for the ‘Widom-601’ sequence, while there is no noticeable difference in the score between SHL ± 5 and SHL ± 6, end regions (SHL ± 7) have a reasonably lower deformation energy cost as compared to other regions, which is also lower than that of the ASP sequence (Fig. 6 D). In comparison with Armeev et al., deformation energy for our trajectory notably exhibits less fluctuations along the sequence. This suggests that the relative ease of deformation at SHL ± 7 is correlated with the higher degree of breathing in the ‘Widom-601’ sequence for our trajectory. Interestingly, bps near SHL ± 1.5 have a notably lower deformation energy cost in the ‘Widom-601’ than the ASP sequence, highlighting the relative ease of its deformability and the unique role of the positioning motif TTTAA. The significant difference in the deformation energy score at SHL ± 1.5 and ± 7 between the sequences correlates with the observed difference in structural changes in DNA, such as if a loop forms or if the DNA end breathes.

Fig. 6.

A color map for the average force constant (kcal/mol) associated with the rise deformation for (A) the ASP and (B) the ‘Widom-601’ nucleosome sequences as obtained from diagonal elements corresponding to the force component of the average 6X6 stiffness matrix. (C) Total deformation energy score as a function of DNA base pair calculated for the selected simulated conformations (see the text) for the ASP (blue) sequence compared with Armeev et al. (red and green). The SHL locations with significantly high deformation scores (red circles) and those with low deformation scores (orange circles) for the ASP sequence are marked. (D) Total deformation energy score as a function of DNA base pair calculated for the selected simulated conformations (see the text) for the ‘Widom-601’ (blue) sequence compared with Armeev et al. (green)

Previously, Tolstorukov et al. 77 proposed a novel roll-slide mechanism for the folding of DNA in the nucleosome. They demonstrated that deformations in these two degrees of freedom occur in such a way that the average twisting of the highly packed superhelix organization of nucleosomal DNA remains the same as that of the naked DNA (~10.4 bp/turn) without the need to peel the DNA off from the histone protein core. Here, we question if a similar hypothesis will explain the observed sequence-dependent dynamics of the nucleosome. First, we characterize which base pair dinucleotide steps primarily govern the local structural deformation for the highly deformed loop/bulge ASP sequence vs. the most strongly open ‘Widom-601’ sequence. We calculate the individual contribution of six different deformation variables (SI Appendix, Figs. S22 and S23). We find a notable difference in roll and shift deformations between the two sequences. The type of dinucleotide base pair step and SHL locations elucidates the mechanism further. For instance, most of the dinucleotide base pairs with significantly high deformation energy scores for these two degrees of freedom belong to purine-purine (RR) or pyrimidine-pyrimidine (YY) type base step (SI Appendix, Table S3). Although the bp location does not exactly match with the bp step with high deformation found in Ref.77, we find a similarity in SHL locations (SHL ± 3 to 5), suggesting that these regions are not only responsible for tight DNA folding around the histone surface but also play an equally important role in controlling the nucleosome dynamics. Indeed, they act as “hinges.” Larger fluctuations in the deformation energy in shift and roll in SHL locations (SHL ± 3 to 5) are consistent for all three sets of ASP simulations, from our laboratory, as well as from Armeev et al (SI Appendix, Figs. S20 and S21). The presence of the YR dinucleotide base step in the minor groove is known to facilitate the kinking required for the binding of DNA with the histone that was explained by their lowest deformation energy cost as compared to the other two types in Ref.77 (most for RY and RR:YY is in between RY and YR). Since we find RR:YY dinucleotide steps with high deformation energy scores for both sequences, we hypothesize that deformations of these base steps govern the structural deformation in metastable states. In contrast, the YR base step is primarily responsible for tight DNA-histone association. Note that 50% (3 out of 6) in comparison to 15% (1 out of 6) YR base steps are found to show high deformation in the ‘Widom-601’ than the ASP sequence (SI Appendix, Table S3). Since YR base steps are easy to deform, this results in more unwrapping as caused by breathing motion for the ‘Widom-601’ sequence. Moreover, the relatively higher deformation cost in SHL ± 2 to 4 is compensated by breathing at SHL ± 7 associated with low deformation (see the high peaks associated with the roll and shift deformation in this region in SI Appendix, Figs. S26B and S27B). Larger fluctuations in the deformation energy in shift and roll in SHL locations (SHL ± 2 to 4) are consistent for both sets of ‘Widom-601’, from our laboratory, as well as from Armeev et al (SI Appendix, Figs. S22, S23, S26 and S27).

Discussion and Conclusions

Herein this study, we performed 12 μs equilibrium molecular dynamics simulations of the nucleosome core particle with full-length histone tails at salt concentrations 10-20 times higher than physiological salt concentration. Using an explicit solvent all-atom approach, the simulations were done for nucleosome systems with the human α-satellite palindromic (ASP) and the ‘Widom-601’ DNA sequence. Such extensive μs—long timescales and atomic-level models allowed us to probe functionally relevant sequence-dependent nucleosome dynamics, such as the breathing/unwrapping of nucleosomal DNA ends, loop/bulge formation, nucleosome sliding/repositioning, and conformational arrangements of histone tails on an atomic level. An analysis of the six dinucleotide DNA deformation degrees of freedom (rise, shift, slide, twist, roll, and tilt) further enabled us to provide insight into the role of DNA sequence on nucleosome dynamics and identify the crucial deformation degrees of freedom and DNA superhelical locations (SHL) in governing such dynamics (SHL± 1.5, ± 5, and ± 7).

Consistent with earlier studies, 43 we observed that SHL ± 5 are potential sites for the formation of a loop/bulge. Results indicated that a “wave-like” DNA motion is necessary for the formation of such a loop, where SHL ± 7 moves toward the histone protein due to condensation of the H2A C-terminal tail. At the same time, SHL ± 5 displaces away from the histone protein due to the condensation of the H2B N-terminal tail. We noticed the formation of a loop of the DNA for the ASP sequence in SHL ± 5. This agrees well with our previous 5 μs equilibrium simulations of the ASP sequence with a different force field set43, as well even longer trajectories as reported by Armeev et al. In contrast, we did not find a noticeable loop at the similar SHL regions for the ‘Widom-601’ sequence, for which we observed spontaneous unwrapping of DNA end regions (SHL ± 7), giving rise to significant breathing of the DNA ends. We note that while the ASP sequences discussed herein tended to form DNA loops in SHL +/−5, the ‘Widom-601’ sequences exhibiting large—scale breathing. We further observed a unique role of the H3 N-terminal tail in modulating the breathing motion, collapsing and forming a helix that stabilizes itself with the neighboring H3 core. Thus, the dynamics of this collapse, and regulation of this dynamics with histone tail PTMs, may regulate the breathing of the NCP, and, ultimately, the degree of compactness of chromatin. So, it may be a combination of N-terminal H3 tail-specific residue contacts, as well as modulation of local elasticity of the DNA in the region of SHL+/− 7, that leads to large-scale breathing motion in the NCP. We note that further computational studies are necessary, of more than just these two sequences, Widom-601 and ASP, to establish the relation between sequence and elasticity. For example, GC-rich and AT-rich sequences were simulated by Winogradoff et al.45, with GC rich staying more tightly bound and AT-rich showing unwrapping. Notably, while the Widom-601 has higher GC-content overall (55.2%) as opposed to ASP (40.8%), the right side of the 601-R sequence is AT-rich (78.6% AT) for the last 14 base pairs but has a lower density of TA steps in its inner quarter. Coincidentally, this is the side that exhibits large-scale opening in our 12-μs trajectory. This is the same side that was observed to unwrap with lower force by Ngo et al.31 With further computational studies, we hope that molecular events and timescales can be used to inform kinetic models of the unwrapping pathway.78

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the NIH (1R15GM146228-01). In addition, this research was supported, in part, by the NSF through grant 1506937. S.M.L. also acknowledges start-up funding from the College of Staten Island and the City University of New York. Anton 2 computer time was provided by the Pittsburgh Supercomputing Center (PSC) through Grant R01GM116961 from the National Institutes of Health. The Anton 2 machine at PSC was generously made available by D.E. Shaw Research. Trajectories are available on https://zenodo.org/record/8253788. Analysis codes are available on https://github.com/CUNY-CSI-Loverde-Laboratory/NUCLEOSOME_SEQUENCE_DEPENDENCE and https://github.com/CUNY-CSI-Loverde-Laboratory/PCA.

We thank Prof. Alexey Shaytan for sharing his trajectories and William Hu for helping with setting up some of the initial simulations.

Footnotes

References

- (1).Kornberg RD; Lorch Y Twenty-five years of the nucleosome, fundamental particle of the eukaryote chromosome. Cell 1999, 98 (3), 285–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Segal E; Fondufe-Mittendorf Y; Chen L; Thåström A; Field Y; Moore IK; Wang J-PZ; Widom J A genomic code for nucleosome positioning. Nature 2006, 442 (7104), 772–778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).McGinty RK; Tan S Nucleosome structure and function. Chemical reviews 2015, 115 (6), 2255–2273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Müller MM; Muir TW Histones: At the crossroads of peptide and protein chemistry. Chemical reviews 2015, 115 (6), 2296–2349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Davey CA; Sargent DF; Luger K; Maeder AW; Richmond TJ Solvent mediated interactions in the structure of the nucleosome core particle at 1.9 å resolution. Journal of molecular biology 2002, 319 (5), 1097–1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Luger K; Mäder AW; Richmond RK; Sargent DF; Richmond TJ Crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle at 2.8 å resolution. Nature 1997, 389 (6648), 251–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Struhl K; Segal E Determinants of nucleosome positioning. Nature structural & molecular biology 2013, 20 (3), 267–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Valouev A; Johnson SM; Boyd SD; Smith CL; Fire AZ; Sidow A Determinants of nucleosome organization in primary human cells. Nature 2011, 474 (7352), 516–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Schones DE; Cui K; Cuddapah S; Roh T-Y; Barski A; Wang Z; Wei G; Zhao K Dynamic regulation of nucleosome positioning in the human genome. Cell 2008, 132 (5), 887–898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Clapier CR; Iwasa J; Cairns BR; Peterson CL Mechanisms of action and regulation of atp-dependent chromatin-remodelling complexes. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology 2017, 18 (7), 407–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Kulić I; Schiessel H Nucleosome repositioning via loop formation. Biophysical journal 2003, 84 (5), 3197–3211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Schiessel H; Widom J; Bruinsma R; Gelbart W Polymer reptation and nucleosome repositioning. Physical review letters 2001, 86 (19), 4414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Lorch Y; Davis B; Kornberg RD Chromatin remodeling by DNA bending, not twisting. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2005, 102 (5), 1329–1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Ranjith P; Yan J; Marko JF Nucleosome hopping and sliding kinetics determined from dynamics of single chromatin fibers in xenopus egg extracts. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2007, 104 (34), 13649–13654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Pasi M; Lavery R Structure and dynamics of DNA loops on nucleosomes studied with atomistic, microsecond-scale molecular dynamics. Nucleic acids research 2016, 44 (11), 5450–5456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Strohner R; Wachsmuth M; Dachauer K; Mazurkiewicz J; Hochstatter J; Rippe K; Längst G A'loop recapture'mechanism for acf-dependent nucleosome remodeling. Nature structural & molecular biology 2005, 12 (8), 683–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Kulić I; Schiessel H Chromatin dynamics: Nucleosomes go mobile through twist defects. Physical review letters 2003, 91 (14), 148103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Richmond TJ; Davey CA The structure of DNA in the nucleosome core. Nature 2003, 423 (6936), 145–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Suto RK; Edayathumangalam RS; White CL; Melander C; Gottesfeld JM; Dervan PB; Luger K Crystal structures of nucleosome core particles in complex with minor groove DNA-binding ligands. Journal of molecular biology 2003, 326 (2), 371–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Gottesfeld JM; Belitsky JM; Melander C; Dervan PB; Luger K Blocking transcription through a nucleosome with synthetic DNA ligands. Journal of molecular biology 2002, 321 (2), 249–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Winger J; Nodelman IM; Levendosky RF; Bowman GD A twist defect mechanism for atp-dependent translocation of nucleosomal DNA. Elife 2018, 7, e34100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Sabantsev A; Levendosky RF; Zhuang X; Bowman GD; Deindl S Direct observation of coordinated DNA movements on the nucleosome during chromatin remodelling. Nature communications 2019, 10 (1), 1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Li M; Xia X; Tian Y; Jia Q; Liu X; Lu Y; Li M; Li X; Chen Z Mechanism of DNA translocation underlying chromatin remodelling by snf2. Nature 2019, 567 (7748), 409–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Blosser TR; Yang JG; Stone MD; Narlikar GJ; Zhuang X Dynamics of nucleosome remodelling by individual acf complexes. Nature 2009, 462 (7276), 1022–1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Deindl S; Hwang WL; Hota SK; Blosser TR; Prasad P; Bartholomew B; Zhuang X Iswi remodelers slide nucleosomes with coordinated multi-base-pair entry steps and single-base-pair exit steps. Cell 2013, 152 (3), 442–452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Eslami-Mossallam B; Schiessel H; van Noort J Nucleosome dynamics: Sequence matters. Advances in colloid and interface science 2016, 232, 101–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Shaytan AK; Armeev GA; Goncearenco A; Zhurkin VB; Landsman D; Panchenko AR Coupling between histone conformations and DNA geometry in nucleosomes on a microsecond timescale: Atomistic insights into nucleosome functions. Journal of molecular biology 2016, 428 (1), 221–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Li Z; Kono H Distinct roles of histone h3 and h2a tails in nucleosome stability. Scientific reports 2016, 6 (1), 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Gansen A; Hauger F; Toth K; Langowski J Single-pair fluorescence resonance energy transfer of nucleosomes in free diffusion: Optimizing stability and resolution of subpopulations. Analytical biochemistry 2007, 368 (2), 193–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Chen Y; Tokuda JM; Topping T; Meisburger SP; Pabit SA; Gloss LM; Pollack L Asymmetric unwrapping of nucleosomal DNA propagates asymmetric opening and dissociation of the histone core. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2017, 114 (2), 334–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Ngo TT; Zhang Q; Zhou R; Yodh JG; Ha T Asymmetric unwrapping of nucleosomes under tension directed by DNA local flexibility. Cell 2015, 160 (6), 1135–1144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Meersseman G; Pennings S; Bradbury EM Mobile nucleosomes--a general behavior. The EMBO journal 1992, 11 (8), 2951–2959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Pennings S; Meersseman G; Bradbury EM Mobility of positioned nucleosomes on 5 s rdna. Journal of molecular biology 1991, 220 (1), 101–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Flaus A; Richmond TJ Positioning and stability of nucleosomes on mmtv 3′ ltr sequences. Journal of molecular biology 1998, 275 (3), 427–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Materese CK; Savelyev A; Papoian GA Counterion atmosphere and hydration patterns near a nucleosome core particle. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2009, 131 (41), 15005–15013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Huertas J; Cojocaru V Breaths, twists, and turns of atomistic nucleosomes. Journal of molecular biology 2021, 433 (6), 166744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Ettig R; Kepper N; Stehr R; Wedemann G; Rippe K Dissecting DNA-histone interactions in the nucleosome by molecular dynamics simulations of DNA unwrapping. Biophysical journal 2011, 101 (8), 1999–2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Rychkov GN; Ilatovskiy AV; Nazarov IB; Shvetsov AV; Lebedev DV; Konev AY; Isaev-Ivanov VV; Onufriev AV Partially assembled nucleosome structures at atomic detail. Biophysical journal 2017, 112 (3), 460–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Zhang B; Zheng W; Papoian GA; Wolynes PG Exploring the free energy landscape of nucleosomes. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2016, 138 (26), 8126–8133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Chakraborty K; Loverde SM Asymmetric breathing motions of nucleosomal DNA and the role of histone tails. The Journal of Chemical Physics 2017, 147 (6), 065101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Erler J; Zhang R; Petridis L; Cheng X; Smith JC; Langowski J The role of histone tails in the nucleosome: A computational study. Biophysical journal 2014, 107 (12), 2911–2922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Morrison EA; Bowerman S; Sylvers KL; Wereszczynski J; Musselman CA The conformation of the histone h3 tail inhibits association of the bptf phd finger with the nucleosome. Elife 2018, 7, e31481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Chakraborty K; Kang M; Loverde SM Molecular mechanism for the role of the h2a and h2b histone tails in nucleosome repositioning. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 2018, 122 (50), 11827–11840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Armeev GA; Kniazeva AS; Komarova GA; Kirpichnikov MP; Shaytan AK Histone dynamics mediate DNA unwrapping and sliding in nucleosomes. Nature communications 2021, 12 (1), 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Winogradoff D; Aksimentiev A Molecular mechanism of spontaneous nucleosome unraveling. Journal of molecular biology 2019, 431 (2), 323–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Ding XQ; Lin XC; Zhang B Stability and folding pathways of tetra-nucleosome from six-dimensional free energy surface. Nature Communications 2021, 12 (1), 1091. DOI: 10.1038/s41467-021-21377-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Edayathumangalam RS; Weyermann P; Dervan PB; Gottesfeld JM; Luger K Nucleosomes in solution exist as a mixture of twist-defect states. Journal of Molecular Biology 2005, 345 (1), 103–114. DOI: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Lequieu J; Schwartz DC; de Pablo JJ In silico evidence for sequence-dependent nucleosome sliding. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2017, 114 (44), E9197–E9205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Niina T; Brandani GB; Tan C; Takada S Sequence-dependent nucleosome sliding in rotation-coupled and uncoupled modes revealed by molecular simulations. PLoS computational biology 2017, 13 (12), e1005880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Brandani GB; Niina T; Tan C; Takada S DNA sliding in nucleosomes via twist defect propagation revealed by molecular simulations. Nucleic acids research 2018, 46 (6), 2788–2801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Nagae F; Brandani GB; Takada S; Terakawa T The lane-switch mechanism for nucleosome repositioning by DNA translocase. Nucleic acids research 2021, 49 (16), 9066–9076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Olson WK; Gorin AA; Lu X-J; Hock LM; Zhurkin VB DNA sequence-dependent deformability deduced from protein–DNA crystal complexes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1998, 95 (19), 11163–11168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Tian C; Kasavajhala K; Belfon KA; Raguette L; Huang H; Migues AN; Bickel J; Wang Y; Pincay J; Wu Q Ff19sb: Amino-acid-specific protein backbone parameters trained against quantum mechanics energy surfaces in solution. Journal of chemical theory and computation 2019, 16 (1), 528–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Zgarbová M; Sponer J; Otyepka M; Cheatham TE III; Galindo-Murillo R; Jurecka P Refinement of the sugar–phosphate backbone torsion beta for amber force fields improves the description of z-and b-DNA. Journal of chemical theory and computation 2015, 11 (12), 5723–5736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Izadi S; Anandakrishnan R; Onufriev AV Building water models: A different approach. The journal of physical chemistry letters 2014, 5 (21), 3863–3871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Joung IS; Cheatham TE III Determination of alkali and halide monovalent ion parameters for use in explicitly solvated biomolecular simulations. The journal of physical chemistry B 2008, 112 (30), 9020–9041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Li Z; Song LF; Li P; Merz KM Jr Systematic parametrization of divalent metal ions for the opc3, opc, tip3p-fb, and tip4p-fb water models. Journal of chemical theory and computation 2020, 16 (7), 4429–4442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Kulkarni M; Yang C; Pak Y Refined alkali metal ion parameters for the opc water model. Bulletin of the Korean Chemical Society 2018, 39 (8), 931–935. [Google Scholar]

- (59).Case DA, B.-S. IY, Brozell SR, Cerutti DS, Cheatham TE III, Cruzeiro VWD, Darden TA, Duke RE, Ghoreishi D, Gilson MK, Gohlke H, Goetz AW, Greene D, Harris R, Homeyer N, Huang Y, Izadi S, Kovalenko A, Kurtzman T, Lee TS, LeGrand S, Li P, Lin C, Liu J, Luchko T, Luo R, Mermelstein DJ, Merz KM, Miao Y, Monard G, Nguyen C, Nguyen H, Omelyan I, Onufriev A, Pan F, Qi R, Roe DR, Roitberg A, Sagui C, Schott-Verdugo S, Shen J, Simmerling CL, Smith J, SalomonFerrer R, Swails J, Walker RC, Wang J, Wei H, Wolf RM, Wu X, Xiao L, York DM and Kollman PA. Amber 2018. University of California, San Francisco.: 2018. [Google Scholar]

- (60).Martyna GJ; Tobias DJ; Klein ML Constant pressure molecular dynamics algorithms. The Journal of chemical physics 1994, 101 (5), 4177–4189. [Google Scholar]

- (61).Feller SE; Zhang Y; Pastor RW; Brooks BR Constant pressure molecular dynamics simulation: The langevin piston method. The Journal of chemical physics 1995, 103 (11), 4613–4621. [Google Scholar]

- (62).Andersen HC Rattle: A “velocity” version of the shake algorithm for molecular dynamics calculations. Journal of computational Physics 1983, 52 (1), 24–34. [Google Scholar]

- (63).Darden T; York D; Pedersen L Particle mesh ewald: An n· log (n) method for ewald sums in large systems. The Journal of chemical physics 1993, 98 (12), 10089–10092. [Google Scholar]

- (64).Shan Y; Klepeis JL; Eastwood MP; Dror RO; Shaw DE Gaussian split ewald: A fast ewald mesh method for molecular simulation. The Journal of chemical physics 2005, 122 (5), 054101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Shaw DE; Grossman JP; Bank JA; Batson B; Butts JA; Chao JC; Deneroff MM; Dror RO; Even A; Fenton CH; et al. Anton 2: Raising the bar for performance and programmability in a special-purpose molecular dynamics supercomputer. In International Conference on High Performance Computing, Networking, Storage and Analysis, New Orleans, LA, Nov 16–21, 2014; 2014; pp 41–53. DOI: 10.1109/sc.2014.9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Chen YJ; Tokuda JM; Topping T; Sutton JL; Meisburger SP; Pabit SA; Gloss LM; Pollack L Revealing transient structures of nucleosomes as DNA unwinds. Nucleic Acids Research 2014, 42 (13), 8767–8776. DOI: 10.1093/nar/gku562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Bilokapic S; Strauss M; Halic M Structural rearrangements of the histone octamer translocate DNA. Nature Communications 2018, 9, 1330. DOI: 10.1038/s41467-018-03677-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).Chen Y; Tokuda JM; Topping T; Sutton JL; Meisburger SP; Pabit SA; Gloss LM; Pollack L Revealing transient structures of nucleosomes as DNA unwinds. Nucleic acids research 2014, 42 (13), 8767–8776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (69).Armeev GA; Kniazeva AS; Komarova GA; Kirpichnikov MP; Shaytan AK Histone dynamics mediate DNA unwrapping and sliding in nucleosomes. Nature Communications 2021, 12 (1). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-021-22636-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (70).Perez A; Lankas F; Luque FJ; Orozco M Towards a molecular dynamics consensus view of b-DNA flexibility. Nucleic Acids Research 2008, 36 (7), 2379–2394. DOI: 10.1093/nar/gkn082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (71).Zgarbova M; Sponer J; Otyepka M; Cheatham TE; Galindo-Murillo R; Jurecka P Refinement of the sugar-phosphate backbone torsion beta for amber force fields improves the description of z- and b-DNA. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation 2015, 11 (12), 5723–5736. DOI: 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (72).Ikebe J; Sakuraba S; Kono H H3 histone tail conformation within the nucleosome and the impact of k14 acetylation studied using enhanced sampling simulation. Plos Computational Biology 2016, 12 (3), e1004788. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (73).Gates LA; Shi JJ; Rohira AD; Feng Q; Zhu BK; Bedford MT; Sagum CA; Jung SY; Qin J; Tsai MJ; et al. Acetylation on histone h3 lysine 9 mediates a switch from transcription initiation to elongation. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2017, 292 (35), 14456–14472. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.M117.802074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (74).Raiymbek G; An SJ; Khurana N; Gopinath S; Larkin A; Biswas S; Trievel RC; Cho US; Ragunathan K An h3k9 methylation-dependent protein interaction regulates the non-enzymatic functions of a putative histone demethylase. Elife 2020, 9, e53155. DOI: 10.7554/elife.53155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (75).Li SS; Shogren-Knaak MA The gcn5 bromodomain of the saga complex facilitates cooperative and cross-tail acetylation of nucleosomes. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2009, 284 (14), 9411–9417. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.M809617200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (76).Blanchet C; Pasi M; Zakrzewska K; Lavery R Curves+ web server for analyzing and visualizing the helical, backbone and groove parameters of nucleic acid structures. Nucleic acids research 2011, 39 (suppl_2), W68–W73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (77).Tolstorukov MY; Colasanti AV; McCandlish DM; Olson WK; Zhurkin VB A novel roll-and-slide mechanism of DNA folding in chromatin: Implications for nucleosome positioning. Journal of molecular biology 2007, 371 (3), 725–738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (78).Mondal A; Kolomeisky AB Why nucleosome breathing dynamics is asymmetric? Biophysical Journal 2024, 123 (3), 226a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.