Abstract

Serotonergic toxicity due to MAO enzyme inhibition is a significant concern when using linezolid to treat MDR-TB. To address this issue, we designed linezolid bioisosteres with a modified acetamidomethyl side chain at the C-5 position of the oxazolidine ring to balance activity and reduce toxicity. Among these bioisosteres, R7 emerged as a promising candidate, demonstrating greater effectiveness against M. tuberculosis (Mtb) H37Rv cells with an MIC of 2.01 μM compared to linezolid (MIC = 2.31 μM). Bioisostere R7 also exhibited remarkable activity (MIC50) against drug-resistant Mtb clinical isolates, with values of 0.14 μM (INHR, inhA+), 0.53 μM (INHR, katG+), 0.24 μM (RIFR, rpoB+), and 0.92 μM (INHR INHR, MDR). Importantly, it was >6.52 times less toxic as compared to the linezolid toward the MAO-A and >64 times toward the MAO-B enzyme, signifying a substantial improvement in its drug safety profile.

Keywords: Linezolid, Bioisosteres, Serotogenic toxicity, Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb), MDR-TB

Linezolid, the first oxazolidinone permitted for the treatment of Gram-positive infections, reduces cellular proliferation by blocking mitochondrial protein synthesis by binding to the ribosomal 50S subunit.1−5In vitro, linezolid has antimycobacterial action against the Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) complex, including multidrug-resistant M. bovis and clinical drug-resistant Mtb.6−9 Prospective and retrospective investigations have indicated that linezolid is efficient in treating multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) and extremely drug-resistant TB (XDR-TB). As a result, linezolid is being used steadily more often in TB patients. However, linezolid has a number of limitations that should restrict its use in the treatment of TB.10−14

The problems associated with linezolid therapy include very common side effects such as non-reversible peripheral neuropathy and optic nerve damage.15−17 More rare but potentially adverse effects are fatal reversible myelosuppression (anemia, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia), lactic acidosis, serotonin syndrome, hypertensive crisis, and neuroleptic malignant syndrome.15−17 Linezolid’s inhibition of MAO enzymes may also lead to drug interactions and an increased risk of developing serotonin syndrome when combined with certain adrenergic and serotonergic agents (Figure 1).15−17 As a result, structural modification of linezolid with improved safety and efficacy profiles is an extremely important prerequisite for TB treatment. While extensive research has been dedicated to enhancing the potency of drugs targeting Mtb, it is often observed that these efforts do not adequately take into account the accompanying toxicity burdens, including the crucial aspect of serotonergic toxicity.18−21

Figure 1.

MAO enzyme inhibition by linezolid.

In continuation of research to resolve the serotonergic toxicity of linezolid,22 and to address toxicity concerns while simultaneously preserving the efficacy against Mtb, the current study deals with the synthesis of acetamidomethyl bioisosteres of linezolid at the C-5 position of the oxazolidinone heterocycle. This approach aims to strike a delicate balance between potent antimycobacterial activity and reduced serotonergic toxicity, ultimately advancing the development of safer and more effective TB treatment.

The detailed workflow of the study is depicted in Figure 2. Initially, we designed bioisosteres (R1–R8) of the acetamidomethyl side chain found at the C-5 position of the linezolid. These bioisosteres were synthesized following reaction, Scheme 1. Subsequently, we evaluated their antimycobacterial activity against both the Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) H37Rv strain and drug resistant clinical Mtb isolates. Bioisosteres showing promising activity were further assessed for serotonergic toxicity (MAO enzyme inhibition) to determine their safety profile. The detail of each step is rigorously discussed in the following section of the manuscript.

Figure 2.

Workflow of the study.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of C-5 Substituted Linezolid Bioisosteres.

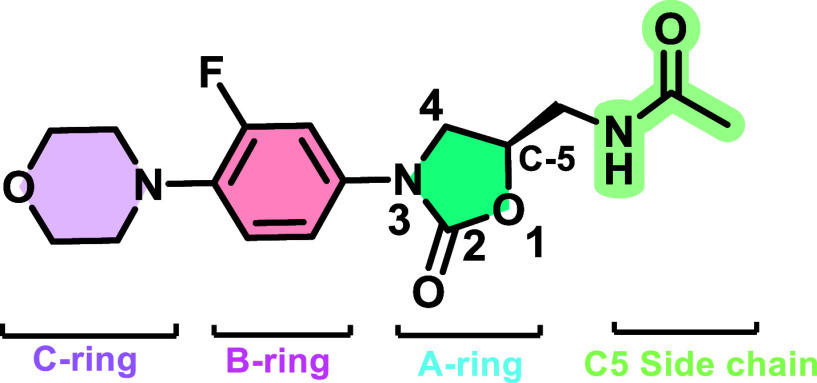

Linezolid’s structure may be split up into four components based on oxazolidinone nomenclature to explain the type of modification performed, as demonstrated in Figure 3.23−25 These components include (i) the A ring, which is the core oxazolidinone heterocycle, (ii) the B ring, which is 3-fluorophenyl linked to the oxazolidinone nitrogen, (iii) the C ring morpholine, which is not always aromatic, and (iv) the C-5 side-chain, which is an acetamidomethyl side chain (Figure 3).23−25

Figure 3.

Recognized structure–activity and toxicity relationship of linezolid.

From the structure–toxicity relationship (STR) of oxazolidinone, it has been observed that structural alterations at the C-5 side chain may influence MAO inhibition.26−28 Various studies on C-5 side-chain modifications to balance the activity–toxicity ratio have been previously published, indicating that this shift provides a ray of hope for overcoming the toxicity burden of linezolid.26−28

Replacements of the oxazolidinone C-5 acetamidomethyl side chain, found to be effective, can mitigate the risk of MAO inhibition, as reported by Renslo.29 Phillips et al. replaced the acetamide group of Linezolid at C-5 position by 1,2,3 triazole to get the compound 1, which was having good antibacterial activity of 1 μg/mL against Staphylococcus aureus with less MAO-B (15.45 μM) inhibition as compared to the Linezolid (1.4 μM).30 Phillips et al., synthesized N-(hydroxy-propionamido)methyl (2) and the N-(hydroxylcyclopropanecarboxamido) methyl (3) analogue of the linezolid by replacing the C-5 acetamidomethyl side chain. Both the compounds spared the MAO-A and MAO-B inhibition as compared to the linezolid, but this modification has also negatively affected the antibacterial activity (Figure 4).31 Based on these notations, a series of acetamidomethyl bioisosteres (R1–R8) were designed through the substitution of C-5 positions of linezolid (Figure 5). The goal was to improve the safety profile while sustaining and potentially boosting the anti-TB activity spectrum through a focused lead optimization effort.

Figure 4.

Impact of C-5 substitution on antibacterial activity and serotogenic toxicity.

Figure 5.

Linezolid bioisosteres of the C-5 acetamidomethyl side chain.

The designed bioisosteres R1–R8 were synthesized as per the reaction in Scheme 1. Pure linezolid was obtained from Optrix Laboratories as a gift sample and was deacylated using methanolic HCl. The deacylated linezolid was further reacted with different substituted sulfonyl chlorides (R1, R4–R8) in DCM with drops of trimethylamine and with substitute carbonyl chlorides (R2 and R3) in pyridine at 0 °C to obtain the C5-substituted linezolid bioisosteres (R1–R8). These bioisosteres were further purified by flash chromatography to get the pure compounds (detailed methodology is discussed in the experimental section of the Supporting Information).

The synthesized bioisosteres R1–R8 were further evaluated for antitubercular activity against Mtb H37Rv using the Microplate Alamar Blue Assay (MABA; Table 1). Comparing the results to the standard antimycobacterial drug linezolid, it is evident that R1, R2, R3, R7, and R8 exhibited higher antimycobacterial activity with MICs of 2.14 μM, 2.08 μM, 1.92 μM, 2.01 μM, and 1.76 μM, respectively, which is stronger than the standard drug linezolid (2.31 μM; Table 1). On the other hand, bioisosteres R4, R5, and R6 showed MIC values greater than >1.87 μg/mL > 1.95 μg/mL and >1.58 μg/mL, indicating weak antimycobacterial activity against Mtb H37Rv at the tested concentrations.

Table 1. Antimycobacterial Activity against M. tuberculosis H37Rv of Linezolid Bioisosteres (n = 2).

The structure–activity relationship revealed that bioisosteres containing methane sulfonamide side chain (R1) and ethane sulfonamide side chain (R7) demonstrated promising activity with an MIC of 2.14 and 2.08 μM, respectively. However, when they were replaced with a butyl sulfonamide substituent, a reduction in activity was observed (R4, MIC > 1.87 μM or >25 μg/mL). This observation indicates that the addition of long aliphatic chain substituents to the C-5 position of the oxazolidinone scaffold resulted in diminished antimycobacterial activities, and a two-carbon-long aliphatic side chain (bioisoster R7) is optimal at the C-5 position for the antimycobacterial activity (Figure 6). On the other hand, the introduction of a 2-thiophene at the C-5 position of the oxazolidinone through a sulfonyl linkage led to an improvement in activity (R8, MIC = 1.76 μM). Aromatic substitution inside the chain significantly decreases the antimycobacterial activity (bioisoster R6 > 1.58 μM) as compared to the heterocyclic substitution (bioisoster R8 1.76 μM). Interestingly, when we compared the antimycobacterial spectrum of the bioisosters R2 and R5 bearing cylopropyl substitution, it has been observed that carbonyl substituted bioisostere (R2) was more potent as compared to the sulfonyl substitution (R5), and vice versa was observed for the bioisosters R3 and R8 (Table 1 and Figure 6).This structure–activity relationship (SAR) indicates that antimycobacterial activity is not solely dependent on the sulfonyl and carbonyl C-5 side chains but also on the type of moiety attached to it. Different substituents can have a significant impact on the overall activity of the compounds, highlighting the importance of optimizing both the C-5 side chain and the attached functional groups to achieve potent antitubercular effects (Table 1 and Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Structure–activity relationship of C-5 substitution of the oxazolidine ring of the linezolid bioisoster.

The most promising bioisosteres R1, R2, R3, R7, and R8 were further evaluated against drug-resistant and multidrug-resistant (MDR) strains of Mtb, as well as a drug-sensitive clinical isolate with no known mutation. The evaluation of linezolid bioisosteres against nonmutant Mtb clinical isolate revealed promising antimycobacterial activity of 0.74 μM (MIC50) for bioisoster R7 as compared to the first line drugs isoniazid and rifampicin (Table 2). The development of resistance in Mtb against isoniazid is well-documented and frequently associated with mutations in specific genes, namely those encoding katG and the inhA promoter. The katG gene encodes the enzyme catalase-peroxidase, which activates isoniazid by converting it to an active form. Mutations in katG can reduce the level of activation of isoniazid, making the drug less effective (high-grade resistance). On the other hand, inhA is involved in fatty acid synthesis, and mutations in the promoter for this gene can lead to decreased binding of the active form of Isoniazid, reducing its inhibitory effect on Mtb (low grade resistance).32,33

Table 2. MIC50 (μM) Values of the Linezolid Bioisosteres against Drug Resistant Mtb Clinical Isolatesa.

inhA+: Low-grade isoniazid resistant clinical isolate with mutation in the promoter region. katG+: High-grade isoniazid resistant clinical isolate with S315T mutation. rpoB+: High-grade rifampicin resistant clinical isolate with S531L mutation. MDR: High-level isoniazid, rifampicin, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide resistance, with mutations in inhA, katG, rpoB (H526D mutation detected), and eis genes. No Mutation: Mtb clinical isolate with no mutation.

In light of these associations between drug resistance and mutations in katG and inhA, a comprehensive evaluation was conducted against isoniazid-resistant clinical isolates of Mtb that carry mutations in these genes. For Mtb clinical isolates with the inhA+ and katG+ mutations, bioisostere R7 displayed a MIC50 value of 0.14 μM and 0.53 μM, respectively, indicating potent inhibitory activity against this mutation as compared to the isoniazid (Table 2). For bioisostere R2, it had MIC50 values of 0.33 μM for inhA+ and 1.53 μM for katG+ strains, indicating potent activity against both mutations as compared to the isoniazid.

The clinical isolate rpoB+ is categorized as a high-grade rifampicin-resistant Mtb strain due to the presence of an S531L mutation in rpoB+.34,35 This genetic mutation modifies the protein structure of RNA polymerase subunit B, leading to a decrease in the ability of rifampicin to inhibit its function. This mutation alters the protein structure of the β subunit of RNA polymerase, making it less susceptible to binding of rifampicin.34,35 As a result, the rifampicin resistant Mtb strain is able to continue to transcribe DNA, even in the presence of rifampicin.34,35 Bioisosteres R1, R2, R3, R7, and R8 exhibited potent inhibitory activity against rpoB+ drug-resistant Mtb clinical isolate as compared to rifampicin. More specifically, bioisostere R7 exhibited potent inhibitory activity against rpoB+ drug resistant Mtb clinical isolate, with MIC50 values of 0.24 μM, compared to the standard drug rifampicin (MIC50 = 28.15 μM) and equipotent to the linezolid (MIC50 = 0.24 μM). Bioisoter R2 also showed promising inhibitory activity with an MIC of 0.82 μM toward the rpoB+ drug resistant Mtb clinical isolate. However, bioisosters R1, R3, and R8 exhibited moderate inhibitory effects, against the rpoB+ isolate.

In addition to evaluating the antimycobacterial activity against drug-resistant Mtb strains carrying specific mutations, we also conducted extensive evaluations of promising compounds on the MDR-TB strain. MDR-TB results from Mtb strains that have developed resistance to at least the most potent first-line drugs, isoniazid and rifampicin. We have used the MDR-TB strain having high high-level isoniazid, rifampicin, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide resistance, with mutations in inhA, katG, rpoB (H526D mutation detected), and eis genes.

Considering linezolid’s association with serotonergic toxicity arising from the inhibition of MAO-A and MAO-B enzymes, the MAO inhibition activities of linezolid bioisosteres were assessed to address potential serotonergic toxicity concerns. The evaluation of the bioisosteres against MDR-TB strains provides essential insights into their potential efficacy against drug-resistant tuberculosis. Bioisoster R7 exhibited potent inhibitory activity, with MIC values of 0.92 μM, akin to those of the standard drug linezolid (MIC = 0.81 μM). This highlights their promise for further exploration as a treatment option for MDR-TB. Bioisoster R2 also exhibited notable inhibitory potential, showing an MIC of 1.99 μM. This is slightly higher than the MIC values of R7, but it is still within the range of effectiveness for MDR-TB treatment. In contrast, bioisosteres R1, R3, and R8 exhibited comparatively moderate inhibitory effects against MDR-TB strains.

The enzyme inhibition data for the MAO enzyme are tabulated in Table 3. All of the potent bioisosteres (R1, R2, R3, R7, and R8) exhibited IC50 values greater than 40 μM, indicating relatively weak inhibitory effects on MAO-A. These bioisosteres demonstrated a limited capacity to inhibit the enzyme, suggesting a lower binding affinity or reduced inhibitory potency compared to linezolid. Notably, bioisostere R7 demonstrated relatively higher IC50 values of >40 μM as compared to the linezolid (IC50 0.61 μM) against the MAO-B enzyme. These values suggested that bioisostere R7 is 64.62 times less toxic as compared to linezolid, implying that these bioisostere R7s may have limited affinity for the enzyme or a less potent inhibitory mechanism, which infers a lower serotonergic toxicity burden.

Table 3. Inhibitions of MAO-A and MAO-B Enzyme by Synthesized Linezolid Bioisosteres.

Overall, the serotonergic toxicity analysis provides valuable insights into the potential safety profiles of the synthesized bioisosters. The results highlight that bioisosters R2, R3, R7, and R8 have limited inhibitory effects on MAO enzymes, indicating a lower likelihood of inducing serotonergic toxicity. Conversely, bioisostere R1 displayed moderate inhibitory activities, suggesting a relatively milder serotonergic toxicity potential. Linezolid, with its robust inhibitory potency, presents a higher potential of inducing serotonergic toxicity.

Structure–toxicity relationship (STR) revealed that replacement of the acetyl group by an aromatic ring moderately reduced the MAO-A and MAO-B enzyme inhibition (bioisoster R6). In the case of aliphatic sulfonyl substitution at the C-5 position of the oxazolidine ring (R1, R4, and R7), it has been noted that the alkyl chain length of two carbons is optimum for reducing the serotonergic toxicity; any increase or decrease in the alkyl chain more or less than two carbon affects MAO-B enzyme inhibition (R1, R4 vs R7). Among the carbonyl and sulfonyl substitution at the C-5 position, carbonyl substituted compounds significantly spared the MAO-B inhibition as compared to the sulfonyl substituted compounds (R2 vs R5 and R3 vs R8; Table 3 and Figure 7). While the compounds R2, R3, and R8 have been previously reported for their antimicrobial properties, this is the first report detailing their activity against TB, MDR-TB, and serotonergic toxicity.36,37

Figure 7.

Structure–toxicity relationship of C-5 substitution of the oxazolidine ring of the linezolid bioisostere for serotogenic toxicity.

The molecular docking study was conducted for all of the synthesized bioisosteres (R1–R8) against the mycobacterial Mtb EthR protein, a transcriptional repressor, to define their potency. Mtb EthR functions by regulating the expression of EthA, inhibiting its transcription through binding to the promoter region of the ethA gene.38 The binding of Mtb EthR to its corepressor impedes the activation of EthA, ultimately resulting in decreased ethionamide second-line drug activation.38 Therefore, the inhibition of Mtb EthR becomes a crucial strategy to efficiently combat Mtb.38 For this purpose, the crystal structure of the Mtb EthR protein complexed with its inhibitor linezolid was obtained via the PDB server (PDB ID: 5NZ0) and subjected to molecular docking analysis using the Glide standard protocol implemented in Schrödinger’s suite. In the active site of Mtb EthR protein, linezolid established a two-hydrogen bond interaction with the Met102 and Tyr148 amino acids and a hydrophobic π–π interaction with the Phe110 residue. Linezolid in the active site is surrounded by the Trp103, Ile107, Phe184, Leu183, Leu177, Leu175, Leu87, Leu90, Ala91, Val152, Ile146, Trp145, and Met142 hydrophobic residues. The active site also contains the Thr105, Asn179, Asn176, and Thr149 polar residues.39−41

According to the anticipated binding modes, the linezolid bioisosteres (R1–R8) were deeply entrenched in the active site of Mtb EthR and participated in many bound and nonbonded interactions with the bordering residues with a strong binding affinity. The docking scores, spanning from −10.81 to −9.60 kcal/mol, revealed the promising binding affinities of the bioisosteres. The potent bioisosters R2 and R7 of the series exhibited a docking score of −10.81 kcal/mol and −10.88 kcal/mol, indicating promising in silico antimycobacterial activity (Table 4). Bioisostere R2 and linezolid formed a hydrogen bond through their amidal NH with Met102 residue at distances of 1.69 and 1.32 Å, respectively (Figure 8). On the other hand, Tyr148 formed a hydrogen bond with the carbonyl group in both cases at distances of 1.64 and 1.61 Å, respectively. Additionally, the fluoro-substituted phenyl ring in both compounds (R2 and linezolid) engaged in hydrophobic interactions with Phe110 at 1.54 and 1.61 Å, respectively. Compound R7, on the other hand, forms a hydrogen bond via its sulfonamido NH with Met102 (1.65 Å). Similar to the R2 and linezolid, R7 also exhibited hydrophobic interaction with Phe110 (1.69 Å) through its fluoro-substituted phenyl rings. The consistent binding pattern observed in the molecular docking of promising compounds R2 and R7 with linezolid against Mtb EthR unveils intriguing insights into their potential mechanisms of antitubercular action. This parallel binding suggests a shared mode of interaction, strengthening the significance of these compounds in the context of tuberculosis treatment (Figure 8).

Table 4. Docking Score of Linezolid Bioisosteres with Mtb EthR Protein (PDB ID: 5NZ0).

Figure 8.

2D and 3D binding interaction of (a,b) bioisoster R2; (c,d) bioisoster R7; and (e,f) linezolid within the binding cavity of Mtb EthR protein (PDB ID: 5NZ0).

The MD simulation was performed to examine the stability of top-scoring bioisostere R2 and R7 in complex with Mtb EthR and to check the physical transformation of protein structural aspects to functional significance. The MD simulation shows interaction strength, pattern, dynamic conformational changes, and intermolecular characteristics.42−45 Using the Desmond MD software, promising bioisosteres R2 and R7 in complex with Mtb EthR protein were chosen for MD simulation up to 100 ns. For elucidating the conformational, structural, and compactness of the protein–ligand complexes, “the root mean square deviation (RMSD), root mean square fluctuation (RMSF), intermolecular hydrogen bond interactions, and radius of gyration (RGyr)” were examined (Table 5).42−45

Table 5. Average, Maximum, and Minimum RMSD, RMSF, Radius of Gyration, and Hydrogen Bond Analysis Values of the Protein–Ligand Complexes.

| parameter | Apo EthR-protein | R2-EthR complex | R7-EthR complex | linezolid-EthR complex |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| protein Cα atoms RMSD (Å) | ||||

| average | 2.48 | 2.98 | 2.55 | 2.90 |

| maximum | 3.38 | 3.99 | 3.83 | 3.65 |

| minimum | 0.99 | 1.02 | 1.23 | 0.99 |

| protein C-α atoms RMSF (Å) | ||||

| average | 1.36 | 1.22 | 1.30 | 1.29 |

| maximum | 6.13 | 5.42 | 5.66 | 5.75 |

| minimum | 0.63 | 0.51 | 0.33 | 0.56 |

| radius of gyration (RGyr) (Å) | ||||

| average | 20.72 | 20.72 | 20.69 | 20.60 |

| maximum | 20.89 | 20.91 | 20.91 | 20.79 |

| minimum | 20.48 | 20.44 | 20.39 | 20.40 |

| hydrogen bond analysis | ||||

| average | 1.44 | 1.06 | 0.84 | |

| maximum | 5.00 | 4.00 | 3.00 | |

| minimum | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

The RMSD serves as a metric for assessing the movement of Cα atoms within a protein’s molecular structure in relation to a reference structure.42 RMSD statistics provide insights into the dynamic nature of molecular systems during simulation, where lower RMSD values indicate greater stability, while higher values suggest increased dynamic behavior.43

Following the initial fluctuations during equilibration, the RMSD values of the R7-EthR complex and linezolid-EthR complex gradually settled around 2.5 Å, with minor adjustments observed until the simulation’s end. The RMSD analysis unveiled distinct structural behaviors. The average RMSD for Apo Mtb EthR was 2.48 Å. However, upon binding with bioisosteres R2, R7, and linezolid, the RMSD averages displayed variations of 2.98, 2.55, and 2.90 Å, respectively. These values suggest that the binding of bioisosteres, especially compound R2 and linezolid, induces more pronounced structural fluctuations in Mtb EthR compared to its Apo form (Figure 9A). Notably, higher fluctuations and a greater RMSD value were observed in compound R2 and the linezolid complex, whereas the R7 complex exhibited relatively lower RMSD profiles. This implies that the R7-EthR complexes maintain more stable interactions with Mtb EthR compared to those with R2-EthR and linezolid. However, it is noteworthy that no pronounced major fluctuations were detected for R2 and R7, indicating that R2 and R7 concomitantly forge robust and consistent structural stability with the Mtb EthR protein.

Figure 9.

MD simulation of 100 ns Trajectory Analysis, A. Time-dependent RMSD of Cα atoms of Mtb EthR Apo Protein, R2- Mtb EthR and R7- Mtb EthR complexes; B. RMSF of individual amino acids of Cα atoms of Mtb EthR Apo Protein, and protein–ligand complexes; C. Time-dependent Radius of Gyration (RGyr) of Mtb EthR Apo Protein, and protein–ligand complexes; D. Time-dependent Hydrogen bond analysis of protein–ligand complexes.

RMSF analysis serves as a valuable parameter in elucidating the dynamic behavior of molecules within three-dimensional protein structures.44 This parameter is employed to assess how individual atoms deviate from their original positions over the course of molecular simulations.44 Essentially, RMSF quantifies the extent of fluctuation or movement shedding light on the conformational flexibility inherent to the protein structure.44 In the case of Apo Mtb EthR, the average RMSF value for the protein C-α atoms is 1.36 Å.

This indicates a moderate level of flexibility, with certain regions of the protein experiencing fluctuations, while others remain relatively stable. The maximum and minimum RMSF values of 6.13 and 0.63 Å, respectively, demonstrate that there are regions within Apo Mtb EthR that exhibit considerable flexibility, while other regions are more rigid. In all of the complexes, including Apo protein, higher fluctuation is observed in the residual index of Ala91-Asp98, which lies in the loop region. In the Apo protein, a higher fluctuation is also visible in Gln191-Ser193, which is not present in the ligand-bound complex. The complex between Mtb EthR and Linezolid displays an average RMSF value of 1.29 Å, which is comparable to the Apo form. In contrast, when bound to compounds R2 and R7, the Mtb EthR complex exhibits a slightly lower average RMSF value of 1.22 and 1.30 Å, respectively, compared to the Apo form.

This suggests that the interaction with R2 and R7 induces a subtle reduction in the overall flexibility of the Mtb EthR protein. During the simulation, both compounds R2 and R7 interacted with amino acids including Leu90, Ala91, Asn101, Met102, Trp103, Thr105, Gly106, Ile107, Phe110, Phe114, Trp138, Met142, Trp145, Tyr148, Thr149, Val152, Asn179, Glu180, Leu183, Phe184, Trp207, Leu87, Gln88, Glu92, Asn93, Pro94, Ala151, and Glu156 (Figure 9B).

The examination of the Radius of Gyration (RGyr) is an important parameter for understanding the folding capability and structural changes in protein–ligand complexes. It elucidates the conformational changes that occur in the three-dimensional structure of the protein following ligand interaction. A high RGyr value suggests that the protein–ligand complex is loosely packed and has a propensity to unfold or is more flexible.42−45

A lower RGyr value, on the other hand, indicates a more compact and stable structure in the complex. The average RGyr values for these complexes were quite consistent and exhibited only marginal differences. Specifically, the Apo Mtb EthR -protein had an average RGyr of 20.72 Å, while the R2-EthR Complex, R7-EthR Complex, and Linezolid- Mtb EthR complex had average RGyr values of 20.72 Å, 20.69 Å, and 20.60 Å, respectively (Figure 9C). These slight variations in the average RGyr values indicate that the binding of ligands such as R2, R7, and Linezolid, did not induce significant changes in the folding competence or structural stability of the Mtb EthR protein. The RGyr graph indicates a notable absence of elevated fluctuation peaks, implying that the binding of ligands did not induce substantial structural changes or alter the folding competence of the Mtb EthR protein. The RGyr values remained relatively consistent across all complexes, indicating that the protein–ligand interactions did not lead to substantial unfolding or increased flexibility in the protein structure.

Intermolecular hydrogen bonding analysis is a crucial aspect of studying ligand–protein interactions.42−45 These hydrogen bonds play a vital role in stabilizing the complex, as they are attractive forces that hold the ligand in place within the protein’s active site. Therefore, a higher number of hydrogen bonds indicates a more robust and stable interaction between the ligand and the protein, which can potentially translate into increased biological activity and efficacy.42−45

Comparing results, it is clear that both R2 and R7 formed a higher average number of hydrogen bonds (1.44 and 1.06, respectively) with Mtb EthR compared to Linezolid (0.84). This suggests that R2 and R7 exhibit stronger and more consistent binding interactions with Mtb EthR. Additionally, both R2 and R7 showed the potential to form a maximum of 5 and 4 hydrogen bonds, respectively indicating moments of strong binding (Figure 9D). In contrast, Linezolid rarely formed more than one hydrogen bond (maximum of 3.00), implying moderate interactions with Mtb EthR. Overall, these findings suggest that R2 and R7 have a higher likelihood of effectively inhibiting Mtb EthR compared to Linezolid, primarily due to their stronger and more stable binding interactions.

In this study, we tackled the significant issue of serotonergic toxicity linked to Linezolid in tuberculosis treatment while maintaining potent anti-TB activity. Inspired by Adam R. Renslo’s insights on the importance of effective acetamidomethyl side-chain replacements at the C-5 position of the oxazolidinone ring to mitigate MAO inhibition risks,29 we engaged in a focused lead optimization effort using the bioisosterism approach.

Among the synthesized bioisosteres, R2 and R7 stand out as promising candidates. Both were more effective against Mtb H37Rv with MIC values of 2.08 and 2.01 μM, respectively, compared to Linezolid (2.31 μM). Bioisostere R2 displayed remarkable activity (MIC50) against drug-resistant Mtb clinical isolates, with values of 0.33 μM (inhA+), 1.53 μM (katG+), 0.82 μM (rpoB+), and 1.99 μM (MDR). Similarly, bioisostere R7 demonstrated significant activity (MIC50) against drug-resistant Mtb clinical isolates, with values of 0.14 μM (inhA+), 0.53 μM (katG+), 0.24 μM (rpoB+), and 0.92 μM (MDR).

Notably, the potent bioisostere R7 was over 6.52 times less toxic than Linezolid toward MAO-A and over 64 times less toxic toward MAO-B enzymes, indicating a substantial improvement in its drug safety profile. Bioisostere R7 thus exhibited remarkable reductions in serotonergic toxicity compared to Linezolid, representing a significant enhancement in safety profiles.

The structure–activity relationship (SAR) and structure-toxicity relationship (STR) were in close agreement regarding both antimycobacterial activity and serotonergic toxicity. A two-carbon aliphatic side chain at the C-5 position was found to be optimal; any increase or decrease in the chain length hindered both the activity and toxicity. Heterocyclic substitution at the C-5 position proved more effective than aromatic substitution in achieving better antimycobacterial activity and reduced serotonergic toxicity. Additionally, carbonyl-substituted compounds at the C-5 position significantly spared MAO-B inhibition compared to that of sulfonyl-substituted compounds.

The molecular docking study of the potent bioisosters R2 and R7 in the series revealed docking scores of −10.81 and −10.88 kcal/mol, respectively, indicating promising in silico antimycobacterial activity against the mycobacterial Mtb EthR protein. Both compounds exhibited crucial interactions with Met102 and Phe110 residues. This parallel binding suggests a common mode of interaction, which further emphasizes the significance of these compounds in the context of tuberculosis treatment. Further MD Simulation for 100 ns confirms the stability of both R2 and R7 in the cavity of the Mtb EthR. Finally, reducing serotonergic toxicity is crucial, as it addresses a critical concern associated with Linezolid. This dual achievement of improved safety and robust anti-TB efficacy underscores the promise of this bioisostere as a potential treatment for MDR-TB, offering hope in the battle against this global health threat.

Acknowledgments

R.T.G. would like to thank the “National Fellowship for Persons with Disabilities (NFPwD)-UGC” (Grant No. NFPWD-2018-20-MAH-6427) for funding the project. T.T. acknowledges financial support by the Research Council of Norway (RCN project numbers #234506, #261669, and #309592) and EU JPIAMR (RCN project #298410).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- SAR

structure–activity relationship

- inhA+

low-grade isoniazid resistant clinical isolate with mutation in the promoter region

- katG+

high-grade isoniazid resistant clinical isolate with S315T mutation

- Mtb

M. tuberculosis

- MDR-TB

multidrug resistant tuberculosis

- MAO

monoamino oxidase

- rpoB+

high-grade rifampicin resistant clinical isolate with S531L mutation

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsmedchemlett.4c00114.

Detailed experimental data as well as spectral characterization data (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Nagiec E. E.; Wu L.; Swaney S. M.; Chosay J. G.; Ross D. E.; Brieland J. K.; Leach K. L. (2005). Oxazolidinones inhibit cellular proliferation via inhibition of mitochondrial protein synthesis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005, 49, 3896–3902. 10.1128/AAC.49.9.3896-3902.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozdogan B.; Appelbaum P. C. Oxazolidinones: activity, mode of action, and mechanism of resistance. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2004, 23, 113–119. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2003.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livermore D. M. Linezolid in vitro: mechanism and antibacterial spectrum. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2003, 51, 9ii–16. 10.1093/jac/dkg249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tato M.; de la Pedrosa E. G.; Cantón R.; Gómez-García I.; Fortún J.; Martín-Davila P.; Baquero F.; Gomez-Mampaso E. In vitro activity of Linezolid against Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex, including multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium bovis isolates. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2006, 28 (1), 75–78. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2006.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ang W.; Ye W.; Sang Z.; Liu Y.; Yang T.; Deng Y.; Luo Y.; Wei Y. Discovery of novel bis-oxazolidinone compounds as potential potent and selective antitubercular agents. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2014, 24 (6), 1496–1501. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B. G.; Yuan X. L.; He D. D.; Hu G. Z.; Miao M. S.; Xu E. P. Research progress on the oxazolidinone drug Linezolid resistance. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2020, 24 (18), 9274–9281. 10.26355/eurrev_202009_23009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashemian S. M. R.; Farhadi T.; Ganjparvar M. Linezolid: a review of its properties, function, and use in critical care. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2018, 12, 1759–1767. 10.2147/DDDT.S164515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meka V. G.; Gold H. S. Antimicrobial resistance to Linezolid. Clin Infect Dis. 2004, 39 (7), 1010–1015. 10.1086/423841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinh D. C.; Rubinstein E. Linezolid: a review of safety and tolerability. J. Infect. 2009, 59, S59–S74. 10.1016/S0163-4453(09)60009-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singla R.; Caminero J.A.; Jaiswal A.; Singla N.; Gupta S.; Bali R.K.; Behera D. Linezolid: an effective, safe and cheap drug for patients failing multidrug-resistant tuberculosis treatment in India. Eur. Respir. J. 2012, 39 (4), 956–962. 10.1183/09031936.00076811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang S.; Yao L.; Hao X.; Zhang X.; Liu G.; Liu X.; Wu M.; Zen L.; Sun H.; Liu Y.; Gu J.; Lin F.; Wang X.; Zhang Z. Efficacy, safety and tolerability of Linezolid for the treatment of XDR-TB: a study in China. Eur. Respir. J. 2015, 45 (1), 161–170. 10.1183/09031936.00035114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M.; Lee J.; Carroll M. W.; et al. Linezolid for treatment of chronic extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis. N Engl J. Med. 2012, 367 (16), 1508–1518. 10.1056/NEJMoa1201964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villar M.; Sotgiu G.; D’Ambrosio L.; Raymundo E.; Fernandes L.; Barbedo J.; Diogo N.; Lange C.; Centis R.; Migliori G. B. Linezolid safety, tolerability and efficacy to treat multidrug- and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis. Eur. Respir. J. 2011, 38 (3), 730–733. 10.1183/09031936.00195210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Migliori G. B.; Eker B.; Richardson M. D.; Sotgiu G.; Zellweger J. P.; Skrahina A.; Ortmann J.; Girardi E.; Hoffmann H.; Besozzi G.; Bevilacqua N.; Kirsten D.; Centis R.; Lange C. TBNET Study Group. A retrospective TBNET assessment of Linezolid safety, tolerability and efficacy in multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Eur. Respir. J. 2009, 34 (2), 387–393. 10.1183/09031936.00009509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anger H. A.; Dworkin F.; Sharma S.; Munsiff S. S.; Nilsen D. M.; Ahuja S. D. Linezolid use for treatment of multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis, New York City, 2000–06. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2010, 65 (4), 775–783. 10.1093/jac/dkq017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schecter G. F.; Scott C.; True L.; Raftery A.; Flood J.; Mase S. Linezolid in the treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2010, 50 (1), 49–55. 10.1086/648675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava S.; Magombedze G.; Koeuth T.; Sherman C.; Pasipanodya J. G.; Raj P.; Wakeland E.; Deshpande D.; Gumbo T. Linezolid Dose That Maximizes Sterilizing Effect While Minimizing Toxicity and Resistance Emergence for Tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 61 (8), e00751-17. 10.1128/AAC.00751-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbachyn M. R.; Hutchinson D. K.; Brickner S. J.; Cynamon M. H.; Kilburn J. O.; Klemens S. P.; Glickman S. E.; Grega K. C.; Hendges S. K.; Toops D. S.; Ford C. W.; Zurenko G. E. Identification of a novel oxazolidinone (U-100480) with potent antimycobacterial activity. J. Med. Chem. 1996, 39 (3), 680–685. 10.1021/jm950956y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo S.; Wang B.; Fu L.; Chen X.; Zhang W.; Huang H.; Lu Y. In vitro and in vivo activity of oxazolidinone candidate OTB-658 against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2021, 65 (11), 10–1128. 10.1128/AAC.00974-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quesnelle C. A.; Gill P.; Roy S.; Dodier M.; Marinier A.; Martel A.; Snyder L. B.; D’Andrea S. V.; Bronson J. J.; Frosco M.; Beaulieu D.; Warr G. A.; DenBleyker K. L.; Stickle T. M.; Yang H.; Chaniewski S. E.; Ferraro C. A.; Taylor D.; Russell J. W.; Santone K. S.; Clarke J.; Drain R. L.; Knipe J. O.; Mosure K.; Barrett J. F. Biaryl isoxazolinone antibacterial agents. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2005, 15 (11), 2728–2733. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ang W.; Ye W.; Sang Z.; Liu Y.; Yang T.; Deng Y.; Luo Y.; Wei Y. Discovery of novel bis-oxazolidinone compounds as potential potent and selective antitubercular agents. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2014, 24 (6), 1496–1501. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girase R. T.; Ahmad I.; Oh J. M.; Kim H.; Mathew B.; Vagolu S. K.; Tønjum T.; Desai N. C.; Sriram D.; Kumari J.; Patel H. M. 2023. Repurposing Azoles to Resolve Serotogenic Toxicity Associated with Linezolid to Combat Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2023, 14 (12), 1754–1759. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.3c00406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palumbo Piccionello A.; Musumeci R.; Cocuzza C.; Fortuna C. G.; Guarcello A.; Pierro P.; Pace A. Synthesis and preliminary antibacterial evaluation of Linezolid-like 1,2,4-oxadiazole derivatives. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 50, 441–448. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw K. J.; Barbachyn M. R. The oxazolidinones: past, present, and future. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 2011, 1241, 48–70. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zurenko G. E.; Gibson J. K.; Shinabarger D. L.; Aristoff P. A.; Ford C. W.; Tarpley W. G. Oxazolidinones: a new class of antibacterials. Curr. Opin Pharmacol. 2001, 1 (5), 470–476. 10.1016/S1471-4892(01)00082-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reck F.; Zhou F.; Girardot M.; Kern G.; Eyermann C. J.; Hales N. J.; Ramsay R. R.; Gravestock M. B. Identification of 4-substituted 1,2,3-triazoles as novel oxazolidinone antibacterial agents with reduced activity against monoamine oxidase A. J. Med. Chem. 2005, 48 (2), 499–506. 10.1021/jm0400810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poel T.-J.; Thomas R. C.; Adams W. J.; Aristoff P. A.; Barbachyn M. R.; Boyer F. E.; Brieland J.; Brideau R.; Brodfuehrer J.; Brown A. P.; Choy A. L.; Dermyer M.; Dority M.; Ford C. W.; Gadwood R. C.; Hanna D.; Hongliang C.; Huband M. D.; Huber C.; Kelly R.; Kim J.-Y.; Martin J. P.; Pagano P. J.; Ross D.; Skerlos L.; Sulavik M. C.; Zhu T.; Zurenko G. E.; Prasad J. V. N. V. Antibacterial oxazolidinones possessing a novel C-5 side chain. (5R)-trans-3-[3-Fluoro-4-(1-oxotetrahydrothiopyran-4-yl)phenyl]-2-oxooxazolidine-5-carboxylic acid amide (PF-00422602), a new lead compound. J. Med. Chem. 2007, 50 (24), 5886–5889. 10.1021/jm070708p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordeev M. F.; Yuan Z. Y. New potent antibacterial oxazolidinone (MRX-I) with an improved class safety profile. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57 (11), 4487–4497. 10.1021/jm401931e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renslo A. R. Antibacterial oxazolidinones: emerging structure-toxicity relationships. Expert Rev. Anti Infect Ther. 2010, 8 (5), 565–574. 10.1586/eri.10.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips O. A.; Sharaf L. H.; D’Silva R.; Udo E. E.; Benov L. Evaluation of the monoamine oxidases inhibitory activity of a small series of 5-(azole) methyl oxazolidinones. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 71, 56–61. 10.1016/j.ejps.2015.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips O. A.; D’Silva R.; Bahta T. O.; Sharaf L. H.; Udo E. E.; Benov L.; Walters D. E. Synthesis and biological evaluation of novel 5-(hydroxamic acid) methyl oxazolidinone derivatives. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 106, 120–131. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2015.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purkan P.; Ihsanawati I.; Natalia D.; Syah Y. M.; Retnoningrum D. S.; Siswanto I. Molecular Analysis of katG Encoding Catalase-Peroxidase from Clinical Isolate of Isoniazid-Resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Med. Life 2018, 11 (2), 160–167. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilchèze C.; Jacobs W. R. Jr. Resistance to Isoniazid and Ethionamide in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: Genes, Mutations, and Causalities. Microbiol Spectr. 2014, 2 (4), MGM2–2013. 10.1128/microbiolspec.MGM2-0014-2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vos M.; Müller B.; Borrell S.; Black P. A.; van Helden P. D.; Warren R. M.; Gagneux S.; Victor T. C. Putative compensatory mutations in the rpoC gene of rifampin-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis are associated with ongoing transmission. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013, 57 (2), 827–832. 10.1128/AAC.01541-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S.; Jena L. Understanding Rifampicin Resistance in Tuberculosis through a Computational Approach. Genomics Inform. 2014, 12 (4), 276–282. 10.5808/GI.2014.12.4.276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsingos C.; Al-Adhami T.; Jamshidi S.; Hind C.; Clifford M.; Mark Sutton J.; Rahman K. M. Synthesis, microbiological evaluation and structure activity relationship analysis of linezolid analogues with different C5-acylamino substituents. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2021, 49, 116397 10.1016/j.bmc.2021.116397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamal A.; Swapna P.; Shetti R. V. C. R. N. C.; Shaik A. B.; Narasimha Rao M.P.; Gupta S. Synthesis, biological evaluation of new oxazolidino-sulfonamides as potential antimicrobial agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 62, 661–669. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2013.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamal A.; Shetti R. V.; Azeeza S.; Swapna P.; Khan M. N.; Khan I. A.; Sharma S.; Abdullah S. T. Anti-tubercular agents. Part 6: synthesis and antimycobacterial activity of novel arylsulfonamido conjugated oxazolidinones. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 46 (3), 893–900. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2010.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikiforov P. O.; Blaszczyk M.; Surade S.; Boshoff H. I.; Sajid A.; Delorme V.; Deboosere N.; Brodin P.; Baulard A. R.; Barry C. E.; Blundell T. L.; Abell C. Fragment-sized EthR inhibitors exhibit exceptionally strong ethionamide boosting effect in whole-cell Mycobacterium tuberculosis assays. ACS Chem. Biol. 2017, 12 (5), 1390–1396. 10.1021/acschembio.7b00091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halder S. K.; Elma F. In silico identification of novel chemical compounds with antituberculosis activity for the inhibition of InhA and EthR proteins from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Clin Tuberc Mycobact Dis. 2021, 24, 100246 10.1016/j.jctube.2021.100246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chikhale R. V.; Eldesoky G. E.; Kolpe M. S.; Suryawanshi V. S.; Patil P. C.; Bhowmick S. Identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis transcriptional repressor EthR inhibitors: Shape-based search and machine learning studies. Heliyon 2024, 10, e26802 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e26802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osmaniye D.; Karaca S.; Kurban B.; Baysal M.; Ahmad I.; Patel H.; Ozkay Y.; Asım Kaplancıklı Z. 2022. Design, synthesis, molecular docking and molecular dynamics studies of novel triazolothiadiazine derivatives containing furan or thiophene rings as anticancer agents. Bioorg Chem. 2022, 122, 105709 10.1016/j.bioorg.2022.105709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayipo Y. O.; Ahmad I.; Najib Y. S.; Sheu S. K.; Patel H.; Mordi M. N. Molecular modelling and structure-activity relationship of a natural derivative of o-hydroxybenzoate as a potent inhibitor of dual NSP3 and NSP12 of SARS-CoV-2: In silico study. J. Biomol Struct Dyn. 2023, 41 (5), 1959–1977. 10.1080/07391102.2022.2026818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayed H. M.; Ramadan M. A.; Salem H. H.; Ahmad I.; Patel H.; Fayed M. A. Phytochemical Investigation, In silico/In vivo Analgesic, and Anti-inflammatory Assessment of the Egyptian Cassia occidentalis L. Steroids 2023, 196, 109245 10.1016/j.steroids.2023.109245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acar Çevik U.; Celik I.; İnce U.; Maryam Z.; Ahmad I.; Patel H.; Özkay Y.; Asım Kaplancıklı Z. Synthesis, biological evaluation, and molecular modeling studies of new 1, 3, 4-thiadiazole derivatives as potent antimicrobial agents. Chem. Biodivers 2023, 20 (3), 202201146 10.1002/cbdv.202201146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.