Abstract

The stem–loop 2 motif (s2m) in SARS-CoV-2 (SCoV-2) is located in the 3′-UTR. Although s2m has been reported to display characteristics of a mobile genomic element that might lead to an evolutionary advantage, its function has remained unknown. The secondary structure of the original SCoV-2 RNA sequence (Wuhan-Hu-1) was determined by NMR in late 2020, delineating the base-pairing pattern and revealing substantial differences in secondary structure compared to SARS-CoV-1 (SCoV-1). The existence of a single G29742–A29756 mismatch in the upper stem of s2m leads to its destabilization and impedes a complete NMR analysis. With Delta, a variant of concern has evolved with one mutation compared to the original sequence that replaces G29742 by U29742. We show here that this mutation results in a more defined structure at ambient temperature accompanied by a rise in melting temperature. Consequently, we were able to identify >90% of the relevant NMR resonances using a combination of selective RNA labeling and filtered 2D NOESY as well as 4D NMR experiments. We present a comprehensive NMR analysis of the secondary structure, (sub)nanosecond dynamics, and ribose conformation of s2m Delta based on heteronuclear 13C NOE and T1 measurements and ribose carbon chemical shift-derived canonical coordinates. We further show that the G29742U mutation in Delta has no influence on the druggability of s2m compared to the Wuhan-Hu-1 sequence. With the assignment at hand, we identify the flexible regions of s2m as the primary site for small molecule binding.

Keywords: COVID-19, s2m, NMR assignment, NMR dynamics, ligand screening

INTRODUCTION

The emergence of the SARS-CoV-2 (SCoV-2) virus resulted in a worldwide pandemic that not only changed our everyday life in a way never seen before but also has given birth to several extensive collaborative initiatives focusing on viral research and drug development. Up to today, the virus has infected more than 690 million people across the world with 6.9 million deaths, and several variants have emerged. Each variant showed a change in characteristics of the virus regarding disease severity and infectivity. The RNA genome of SCoV-2 consists of ∼30,000 nt. It does not only encode for the viral proteins but also harbors highly structured 3′- and 5′-untranslated regions (UTRs). The presence of these structured regions was proposed early in the pandemic with the help of computational predictions (Rangan et al. 2020) and experimentally verified by NMR and DMS footprinting (Wacker et al. 2020). It is known that the UTRs of coronaviruses play important regulatory roles in processes like genome replication and translation (Yang and Leibowitz 2015). The stem–loop 2 motif (s2m) is part of the hypervariable region (HVR) of the 3′-UTR (Goebel et al. 2007) and found in position 29,728–29,768 in the SCoV-2 RNA genome (Wu et al. 2020). In contrast to the entire HVR, the 43-nt-long s2m is more conserved even between only distantly related viruses (Tengs et al. 2013). It was first described in 1997 in Astroviruses (Monceyron et al. 1997) and has subsequently been detected in Caliciviruses, Picornaviruses, and Coronaviruses (Kofstad and Jonassen 2011). Its spread between different viruses suggests that it can be transferred from one virus to another. Supporting this hypothesis, a “MixOmicron” SCoV-2 hybrid was reported where an s2m-containing 2500- to 3000-nt region from Omicron 21K/BA.1 has been transferred to Omicron 21L/BA.2. In the resulting genome, the truncated s2m version that is present in most Omicron lineages (Frye et al. 2023) is replaced with the full-length s2m from Omicron 21K/BA.1, emphasizing the mobile nature of this RNA element (Colson et al. 2022). The function of s2m has remained uncertain, but its high degree of conservation suggests that an evolutionary advantage is connected to it.

The proposed function of s2m is host-related rather than viral (Tengs et al. 2013). This hypothesis is supported by the lack of conservation in the flanking regions of the RNA element compared to s2m itself. In contrast to the only distantly related viruses where s2m occurs, hosts infected by s2m-containing viruses are more closely related from an evolutionary perspective. It has been proposed that s2m plays a role in different processes such as hijacking of the host protein machinery (Robertson et al. 2005), RNAi-like gene regulation of host genes (Tengs et al. 2013), viral replication (Gilbert and Tengs 2021), immune evasion through interaction with host miRNA-1307-3p and genomic dimerization (Imperatore et al. 2022), or protection of the viral RNA against degradation (Tengs and Jonassen 2016). Additionally, it has been shown that s2m can bind to the viral N-protein (Padroni et al. 2023).

S2m is one of the few RNAs of betacoronaviruses for which X-ray data have been reported. In 2005, the crystal structure for SCoV-1 s2m was solved (Robertson et al. 2005). In this crystal structure, s2m shows a unique secondary structure with two perpendicular stems, a GNRA-like apical pentaloop, a purine-rich internal loop, and a 7-nt asymmetric internal loop. Close to the apical loop, a 90° kink of the helix axis is formed that is mediated by two unpaired nucleotides (Robertson et al. 2005). Compared to SCoV-1, s2m in SCoV-2 shows two mutations (U29732C and G29758U). These two mutations drastically alter the secondary structure of the RNA. 1H, 1H NOESY, 1H, 15N BEST-TROSY, and 1H,15N HNN-COSY NMR experiments showed that the upper stem of SCoV-2 s2m adopts a completely different base-pairing pattern. Here, s2m contains a nonaloop and two stems separated by a large 10-nt internal loop, whereas the upper stem contains an internal G-A mismatch (Wacker et al. 2020).

Some homology or bioinformatic approaches used the already published secondary structure of SCoV-1 s2m as a starting point to determine the influence of the mutations in SCoV-2, stating no significant change in secondary structure between SCoV-1 and SCoV-2 (Ryder et al. 2021). Others used the NMR-derived secondary structure published for the Wuhan-Hu-1 version by our group (Wacker et al. 2020) as a starting model (Rangan et al. 2021; Kensinger et al. 2023). Alternatively, a secondary structure deviating from SCoV-1 s2m based on RNA structure probing data was used (Manfredonia et al. 2020). One study (Jiang et al. 2023) functionally characterized the s2m element to assess the impact of s2m on viral growth of SCoV-2, both in cell cultures (in vitro) and Syrian hamster models (in vivo). All these reports feature substantially different secondary structures, warranting detailed high-resolution structural work as reported here. Although previous publications suggested an evolutionary advantage associated with s2m, the viral fitness in Syrian hamster models did not change upon deletion of s2m. However, the study acknowledges its limitations and leaves open the possibility that s2m may still play a significant role concerning cell line and host dependence. The intriguing question that remains unanswered is why the s2m element is highly conserved across different variants, even though the RNA element appears to lack a critical functional role. Further research is required to explore this and gain a deeper understanding of s2m's significance in the context of viral growth and evolution.

Up to now, therapeutic strategies to combat SCoV-2 focused either on the development of vaccines that induce the production or present (variants of the) surface receptor protein spike to stimulate the host immune response (Pfizer-BioNTech, Moderna, Johnson & Johnson, Astrazeneca, Novavax) or on the development of low molecular mass molecules (small molecules) that target especially the main protease of SCoV-2 (Macchiagodena et al. 2020; Zhang et al. 2020; Cantrelle et al. 2021; Günther et al. 2021). Both strategies, although effective, inevitably tend to be sensitive toward evolutionary pressure to evade the immune response or the antiviral agent. To provide a broader approach, our project, COVID19-NMR Consortium (Duchardt-Ferner et al. 2023), has focused on screening the entire proteome (Berg et al. 2022) and RNA genome of SCoV-2 to identify binding fragments for further medicinal chemistry campaigns. One underestimated but promising research area is the development of drugs targeting RNA, which could potentially revolutionize antiviral treatment. Although the function remains elusive, it is very likely that s2m is involved in some of the proposed processes, and considering its conservation, this motive presents an excellent drug target. It has successfully been targeted with antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) (Lulla et al. 2021), l-DNA aptamers (Li and Sczepanski 2022), and antiviral compounds (Simba-Lahuasi et al. 2022).

We here report on the NMR characterization of the Delta variant of s2m, including near to complete chemical shift assignment, 13C-based delineation of local subnanosecond dynamics within this RNA element, and the determination of binding epitopes and affinities for small molecules from a library containing 786 compounds. For the Wuhan-Hu-1 version of s2m, there have been 10 hits with typical KDs ranging from 64 µM to 1.3 mM, whereas the best binder showed an affinity of 6 µM (Sreeramulu et al. 2021). We show that the binding affinities are not affected by the mutation observed in the Delta variant and identify preferred sites for small molecule binding.

RESULTS

Comparison between secondary structures of SCoV-1, SCoV-2, and SCoV-2 (Delta)

The crystal structure for s2m SCoV-1 (Fig. 1A,B) consists of two stems, a purine-rich internal loop, a 7-nt internal loop, and a GNRA-like pentaloop and presents a 90° kink close to the apical loop (Robertson et al. 2005). Two mutations (U → C29732 in the lower stem and G → U29758 in the upper stem) in s2m SCoV-2 alter the secondary structure of the upper stem significantly (Wacker et al. 2020). The original Wuhan-Hu-1 version of s2m of SCoV-2 consists of two stems separated by a large 10-nt internal loop, an internal unstable G-A mismatch in the upper stem, and a nonaloop (Fig. 1C). The mutation that occurred in the SCoV-2 Delta variant from 29742G to 29742U suggests the formation of a base pair between U29742 and A29756, leading to a stabilized 6-bp upper stem that is not disrupted by a G-A mismatch (Fig. 1D). This, in turn, may stabilize the global structure and the loop-closing noncanonical G-U base pair and should not alter the rest of the secondary structure.

FIGURE 1.

(A) Crystal structure of s2m SCoV-1 and secondary structures of s2m SCoV-1 (B), SCoV-2 (C), and SCoV-2 Delta (D). The crystal structure for SCoV-1 (Robertson et al. 2005) was taken from the pdb: 1XJR. Nucleotides that differ between SCoV-1 and SCoV-2 are highlighted in red and the Delta mutation is highlighted in magenta. The new base pair that can be formed in Delta is shown in a gray box. The numbering of nucleotides corresponds to the position in the genome −29,000. The nucleotide notation for SCoV-1 is adjusted to match the notation in SCoV-2. (E) Sequence alignment of s2m SCoV-1, SCoV-2, and SCoV-2 Delta. Nucleotides that differ compared to s2m SCoV-2 are highlighted in red or magenta with a gray box.

NMR chemical shift assignment of s2m Delta, delineation of secondary structure, and analysis of thermal stability

Imino proton assignment

The RNA sequence of s2m investigated in this study comprises nucleotides 29,728–29,763. To facilitate in vitro transcription and stabilization of the lower stem region of the RNA, two artificial GC base pairs (G−2, G−1, C+ 2, C + 1) were added (Fig. 2B). Others have reported a kissing dimer and extended duplex of this RNA in the presence of Mg2+ ions (Cunningham et al. 2023). Higher sample concentrations in our experiments compared to this study could potentially lead to dimerization even in the absence of magnesium ions. Because we are focusing here on the monomeric s2m Delta this state was obtained via a folding protocol at 95°C and verified via native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) (see Materials and Methods).

FIGURE 2.

Secondary structure, imino proton assignment, and transfer to aromatic protons of s2m Delta. The assignment is annotated in each spectrum. The numbering of nucleotides corresponds to the position in the genome −29,000. Additionally, introduced terminal G-C base pairs are annotated as G−1/2 or C + 1/2, respectively. Nucleotides labeled in gray belong to the lower stem and nucleotides labeled in magenta belong to the upper stem. (A) 1H, 1H NOESY spectrum of the imino proton region. (B) 1H, 15N BEST-TROSY of base-paired region of s2m Delta. A schematic representation of the secondary structure is shown in the lower right corner. (C) HCCNH spectrum showing H1-C6 and H3-C8 correlations for base-paired Us and Gs. (D) 1H, 13C HSQC of the aromatic region showing C6-H6 and C8-H8 correlations for base-paired Us and Gs, respectively. Resonances that could be assigned in the HCCNH spectrum are annotated.

With characteristic 15N chemical shifts of Gs and Us, these nucleobases can easily be distinguished in 1H, 15N spectra, as 15N chemical shifts of imino protons (N1-H1) of G are expected between 145 and 148 ppm and of U (N3-H3) between 157 and 162 ppm (Fürtig et al. 2003). Because of solvent exchange, only base-paired nucleotides yield NMR peaks for the imino protons. In total, 12 out of 13 expected 1H, 15N resonances could be detected in 1H, 15N BEST-TROSY spectra (Fig. 2B) at 298 K. Five of these resonances could be assigned to Us (N3-H3) and seven to Gs (N1-H1) based on their characteristic chemical shift. The missing G (N1-H1) resonance can be assigned to G−2 as part of the closing G-C base pair. Missing signals are expected as the imino proton is likely in exchange with the solvent and for this reason not detectable at 298 K. In 1H, 1H NOESY spectra NOE cross peaks of adjacent base pairs are to be expected, where one base-paired imino proton is in close proximity to another one. Analysis of these sequential NOE cross peaks led to a full assignment of all imino protons of both base-paired regions. The two observable sequential walks were GGUGUG and GUUGUUG(G), whereas G−2 is only observable at low temperatures (Supplemental Fig. S1), confirming the previously described secondary structure (Wacker et al. 2020). As for the Wuhan-Hu-1 version, the stable 7-bp lower stem is separated from the upper stem by an unpaired dynamic internal loop region. It is formed by 6 nt on the 5′-strand and 4 nt on the 3′-strand and shows no imino proton resonances due to solvent exchange. The proposed formation of the U29742–A29756 bp in the upper stem of the Delta mutant could be confirmed in both the 1H, 1H NOESY and 1H, 15N BEST-TROSY spectra (Fig. 2A,B).

At low temperatures, we additionally observed an NOE cross peak to G29744, which we assigned to originate from the G29745 imino signal as part of the GU loop closing base pair. Typical 1H and 15N chemical shifts detected in 1H, 15N BEST-TROSY spectra confirmed this (Supplemental Fig. S1). This base pair could not be detected at 298 K. Such loss of imino signal at higher temperatures is typically linked to accelerated base pair opening and chemical exchange with the solvent. We conclude that the base pair is dynamic and unstable. Additionally, the G−2 (H1-N1) resonance that could not be detected at 298 K is visible at 283 K.

Moving on from the imino proton assignment we could identify aromatic resonances of the base-paired Gs and Us via 1H, 13C HSQC, and HCCNH experiments of a 13C, 15N uniformly labeled sample. The latter experiment correlates the chemical shift of an H1 or H3 proton with its C8 or C6 aromatic carbon, respectively. In 1H, 13C HSQCs, we could assign peaks using this information resulting in an assignment of the aromatic protons of Gs and Us within the two stems (Fig. 2C,D).

Melting point determination

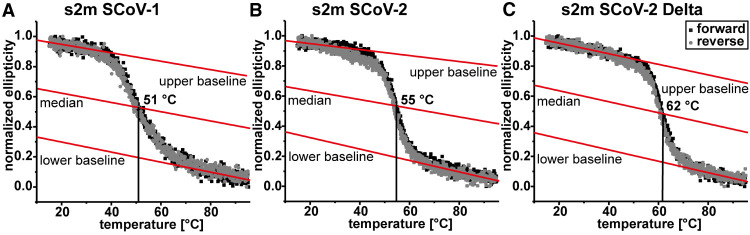

To investigate the stability of the RNA for the different mutants, we measured CD melting curves of SCoV-1, SCoV-2, and SCoV-2 Delta versions of s2m. Of all three constructs, s2m Delta showed the highest melting point of 62°C, which is significantly higher than the temperatures measured for the SCoV-1 (51°C) and SCoV-2 (55°C) versions (Fig. 3). This is in line with our proposed secondary structure and the finding that the upper stem now forms an uninterrupted helical segment of 6 bp.

FIGURE 3.

CD melting curves of s2m SCoV-1 (A), SCoV-2 (B), and Delta (C). All melting points are annotated. Black and gray curves correspond to measurements with increasing (forward) or decreasing (reverse) temperatures, respectively. Baselines and medians are shown as red lines.

Aromatic C6H6/C8H8 and ribose C1′H1′ assignment via 4D NMR

Using a 4D-HMQC-NOESY-HMQC experiment (Stanek et al. 2013), sequential assignment of 44 out of 45 C6H6/C8H8 and C1′H1′ resonances could be achieved. For this assignment, we started with aromatic peaks (Fig. 4A) that could be assigned before in HCCNH or 2D-NOESY spectra. From there, the chemical shifts of the 13C- and 1H dimensions were both transferred to the 4D spectrum. The resulting HSQC-like plane then only showed C1′H1′ resonances with an NOE cross peak to the selected aromatic proton (one peak for nucleotide [i] and one for nucleotide [i − 1] for most resonances) (Fig. 4B). By comparing the 4D plane with a 1H, 13C HSQC for the C1′H1′ region, these resonances could easily be assigned (Fig. 4C). As an example of the sequential walk using the 4D experiment, the loop assignment is shown in Supplemental Figure S2. The assignment procedure was inverted for difficult assignments starting from the C1′H1′ shifts and moving to the aromatic plane of the 4D spectrum. The aromatic plane then showed one peak for nucleotide (i) and a second peak for nucleotide (i + 1). In addition to the 4D-HMQC-NOESY-HMQC, HCN and CNC spectra as well as HCCNH and CPMG-NOESY experiments were used to assign C1′H1′ and C6H6/C8H8 resonances based on the imino assignment of the construct. The 4D experiment enabled us to observe continuous NOESY connectivities for the lower stem and for the upper stem including the loop. The most challenging region regarding the assignment was the internal loop region between nucleotides C29733–C29738 and U29760–C29764, respectively (Fig. 1), that could only be assigned by combining all previously mentioned experiments.

FIGURE 4.

Aromatic C6H6/C8H8 and ribose C1′H1′ assignment via 4D-HMQC-NOESY-HMQC. (A) 1H, 13C HSQC of the aromatic region of s2m Delta. The annotation and chemical shifts of nucleotide A735 are highlighted in blue. (B) 4D-HMQC-NOESY-HMQC C1′H1′ plane of A735. By transferring the aromatic chemical shifts (blue box) to the 4D a 1H, 13C HSQC-like plane of the C1′H1′ region is displayed. (C) Overview of relevant magnetization transfers and secondary structure. (D) Overlay of the 1H, 13C HSQC (ribose C1′H1′ region) of s2m Delta with the 4D plane of nucleotide A735. The resonance assignment for nucleotide A735 is highlighted in red. The resonance assignment of all nucleotides is annotated and the notation of nucleotides corresponds to the position in the genome −29,000.

Ribose assignment (C2′–C5′) based on 13C-filtered NOESY and 3D TOCSY

For the assignment of the C2′–C5′ resonances, the problem of signal overlap was particularly challenging because the stem nucleotides showed very similar 13C chemical shifts. To alleviate this restricted chemical shift resolution, we used 13C-filtered NOESY (Otting and Wüthrich 1989) and 3D-TOCSY spectra of selectively labeled samples (AC and GU 13C, 15N labeled). These combined experiments enabled a separate assignment of the 13C and 1H shifts. In turn, this allowed unambiguous identification of most peaks in the HSQC spectra despite insufficient resolution of the HSQCs, when considered alone. The 1H chemical shifts were obtained mainly via the filtered NOESY spectra using both the aromatic and H1′ region in the direct dimension. In the {F1, F2}-filtered spectrum, peaks were only visible when both protons were attached to a 12C carbon filtering out all protons that were connected to 13C. As an example, in our AC-labeled sample, cross peaks were visible from G29757 to U29758 but not to A29756. Consequently, this significantly diminished the number of signals and subsequently reduced the signal overlap.

Cross peaks were observed from the aromatic (or ribose H1′) protons intraresidual to all other ribose protons (H2′–H5″) and interresidual to H2′ and H3′ protons of the sequential nucleotide (Fig. 5A). The forward (fw)-HCCH-TOCSY (Schwalbe et al. 1995; Glaser et al. 1996) was analyzed by selecting different 1H, 13C-planes via the H1′ chemical shifts (Fig. 5C). In an ideal case, 1H and 13C chemical shifts can be obtained for all ribose protons of a nucleotide. In fact, most H2′C2′, H3′C3′, and H4′C4′ resonances can be assigned using this experiment. In addition, an HCC(H)-TOCSY was recorded that enabled the assignment of all ribose 13C chemical shifts connected to a C1′H1′ resonance (Fig. 5D). In this case, the 1H, 13C-planes were selected via the C1′ chemical shifts. Figure 5 shows which experiments were used for the assignments of 13C and 1H chemical shifts, respectively. A schematic representation of the assignment strategy is given in the upper right panel (Fig. 5B).

FIGURE 5.

Assignment of C2′–C5′ resonances via 13C-filtered NOESY and TOCSY spectra of selectively labeled s2m Delta samples. The resonance assignments for nucleotide C732 are annotated as an example. The notation of nucleotides corresponds to the position in the genome −29,000. (A) 13C-filtered NOESY of the aromatic to ribose region. (B) Overview of applied experiments for both selectively labeled samples and assignments derived from this. (C) fw-HCCH-TOCSY plane of nucleotide C732 (red) in overlay with a constant time HSQC (black) of the ribose region. The plane was selected via the H1′ chemical shift of nucleotide C732 (F1 = 5.3 ppm).

Using the previously mentioned strategy including the 4D-HMQC-NOESY-HMQC and 13C-filtered NOESY, >90% of all structurally relevant NMR resonances were unambiguously assigned. For the aromatic C6H6/C8H8 and the C1′H1′ chemical shifts, 44 of 45 resonances could be assigned with only nucleotide G738 missing, which was overlapping with other signals and in an adverse exchange regime leading to a missing peak in the 4D. For the remainder of the ribose resonances, 145 out of 180 13C chemical shifts and 201 of 225 1H chemical shifts could be assigned with a completeness ranging from 71% (C4′) to 98% (H2′). The complete assignment is reported in Supplemental Tables S1 and S2.

Canonical coordinates

Based on the complete ribose assignment of s2m Delta, we calculated canonical coordinates to determine the conformation of the ribofuranosyl ring of each nucleotide and the exocyclic torsion angle γ (Fig. 6). This empirical parameterization based on the 13C chemical shifts enables distinction between C3′ endo and C2′ endo conformation and was carried out as described previously (Ebrahimi et al. 2001; Cherepanov et al. 2010). Our results suggest a canonical C3′ endo conformation for both helical regions, the 3′ side of the dynamic internal loop and the lower part of the apical loop. This is typical for canonical A-form helices. In contrast, most of the loop nucleotides and the 5′ side of the internal loop adopt a C2′ endo conformation. For the internal loop nucleotides G736 and G737, we were not able to achieve a complete ribose assignment, but characteristic C4′ chemical shifts (84.46, 84.32 ppm) indicate C2′ endo conformation for these nucleotides. In the same manner, the loop nucleotide A752 can be considered as C2′ endo as it shows characteristic C1′ (90.86 ppm), C2′ (76.25 ppm), and C4′ (84.74 ppm) chemical shifts. For G745 and U753 the assigned chemical shifts predict a more C3′ endo conformation, which is in line with the previously mentioned unstable G-U base pair that is formed at low temperatures and extends the 6-bp upper stem. We excluded the C + 2 nt as it forms a cyclic phosphate after HDV-induced cleavage (see Materials and Methods).

FIGURE 6.

Canonical coordinates based on ribose carbon shifts of s2m. (A) Each square corresponds to a can1*/can2* combination of 1 nt derived from its ribose 13C chemical shifts. Specific nucleotides are annotated. Red squares indicate C2′ endo and black squares indicate C3′ endo conformation. Loop and internal loop nucleotides are annotated. (B) Secondary structure of s2m Delta.

Dynamics of the loop and internal loop region

Heteronuclear 13C T1 relaxation and NOE

To investigate the dynamics of s2m especially in the apical and internal loop regions, we measured heteronuclear 13C T1-relaxation rates and NOE. All measurements were conducted for the C6H6/C8H8 aromatic resonances (Fig. 7A) and for the C1′H1′ ribose resonances (Fig. 7B). For the apical loop region (pink), we measured significantly higher overall hetNOE rates. For the aromatic loop signals, we measured a mean hetNOE of 1.30 compared to a mean value of 1.14 for the stem. In addition, we observed that the hetNOE gradually increases with distance relative to the stem (e.g., U748 [1.37] and A749 [1.38] showed the highest hetNOE). For the aromatic internal loop residues, the picture was similar although the difference was not as prominent as for the loop (1.21 internal loop, 1.14 stem). The R1 rates for the aromatic signals showed a similar trend with a mean rate of 1.98 sec−1 for the loop compared to 1.55 sec−1 for the stem. However, it is worth noting that the R1 rates in the loop showed reduced values for all A nucleotides (A746, A749, A751) that are symmetrically distributed within the loop. The flexibility of the internal loop region as it is suggested from the hetNOE could in this case not be confirmed by higher R1 rates.

FIGURE 7.

1H, 13C R1 rates (upper panels), and heteronuclear NOE of s2m Delta (lower panels). For all measurements, separate experiments were recorded for (A) aromatic C6H6/C8H8 and (B) ribose C1′H1′ resonances. The secondary structure of the RNA as determined by NMR is given at the top. The loop region (pink) and internal loop region (green) are highlighted in the plots. The notation of nucleotides corresponds to the position in the genome −29,000.

In contrast to the aromatic protons, the chemical environment of H1′ was generally more similar, which led to an easier interpretation of the R1 rates and the hetNOE (Fig. 7B). For the flexible regions, the mean hetNOEs were again significantly higher (internal loop: 1.13, loop: 1.23) than for the stem regions (1.08). The highest hetNOEs were detected for the nucleotides U748, A749, and C750 (1.32). These nucleotides represent the tip of the loop and are the furthest away from the upper stem. The R1 rates for the C1′ resonances showed the same trend with mean rates of 1.23 sec−1 for the loop compared with 0.74 sec−1 for the stem. In this case, no variations are observed for A746, A749, and A751, and the internal loop region shows slightly higher mean hetNOEs than the stem (0.89 vs. 0.74 sec−1). Within the loop, the same gradual increase in R1 rates was observable as for the hetNOE values. For nucleotides G−2, G−1, and C + 2, higher hetNOE values and/or R1 rates indicating increased dynamics are observed due to the instability of closing base pairs.

Overall, the relaxation and hetNOE data confirmed the dynamic nature of the unpaired regions of s2m. In particular, the loop must be regarded as highly flexible with an increased flexibility for the nucleotides at the tip of the nonaloop. Structure calculations of this RNA will, therefore, not yield a tight structure bundle in the loop region but show a variety of states.

Druggability of s2m Delta

To investigate the druggability of s2m, ligand- and RNA-based titrations were carried out. In an earlier fragment-based NMR screening approach, 10 hits out of 768 fragments were identified for SCoV-2 s2m, and KD values were estimated in ligand-based titrations (Sreeramulu et al. 2021). We now determined values for s2m Delta with seven of these initial hits using 1H-1D NMR titrations with constant ligand concentration (100 µM) and increasing RNA concentration (0–250 µM). An overview of the determined affinities is given in Figure 8E. 1D spectra and fits for all ligands are given in Supplemental Figure S4. A comparison of all affinities between s2m SCoV-2 and s2m Delta showed an overall good agreement except for ligand P5H08 in which a significantly lower affinity was detected for the Delta version ( > 1 mM vs. 200 µM). An explanation for this could be that the ligand might interact with the upper stem of the motif close to the G-A mismatch that is present in the Wuhan-Hu-1 construct. For both s2m versions, the ligands P6E06 and P4C11 showed the highest affinity ( = 120–212 µM). We conclude that the druggability of s2m does not change significantly between the two mutants.

FIGURE 8.

(A) Determination of estimated KD via ligand-detected 1H-1D NMR titration. (B) RNA-based Euclidean distance plot to determine the binding site of P4C11 to s2m. The structural formula of the ligand is shown in the upper right corner. Internal loop residues are highlighted in green and loop residues are highlighted in magenta. A threshold of twofold the standard deviation was used. (C) 1H, 13C HSQC spectra of the aromatic region of s2m Delta (100 µM) with 0 µM (black) and 500 µM (yellow) P4C11. Resonance assignments are annotated and the notation of nucleotides corresponds to the position in the genome −29,000. Loop resonances are labeled in magenta and internal loop resonances are labeled in green. (D) The secondary structure of s2m Delta is colored with HSQC-based chemical shift perturbation (CSP) heatmap (strong: red, weak: blue) and red corresponds to the maximum CSP detected. (E) Overview of values of different ligands for s2m SCoV-2 and s2m Delta.

The binding behavior of P4C11 and P6E06 was further analyzed via analysis of CSPs (mapping) in RNA detected 1H, 13C HSQC spectra of the aromatic region using a fivefold excess of ligands (Figs. 8 and 9). Here, the chemical shift differences between spectra with and without added ligands were determined and plotted in histograms (Figs. 8B and 9B). To visualize the largest changes in chemical shift, CSPs were mapped on the secondary structure of s2m Delta (Figs. 8D and 9D). Nucleotides that revealed the largest CSPs were considered to be part of the binding pocket. Using this approach, the binding site of both ligands could be localized in the internal loop region of the RNA. For P4C11, more prominent effects were observed on the 3′ side of the internal loop where all 4 nt (UACA) showed significant shifts with C762 and A763 shifting the most. Similarly, for P6E06, C762 and A763 were shifting the most but also the 5′ site of the internal loop shows significant CSPs at position A735 and G736. Residues further away from this region including the nonaloop showed significantly lower CSPs of the aromatic resonances. The same procedure was carried out for the C1′H1′ resonances upon the addition of P4C11 (Supplemental Fig. S5) and P6E06 (Supplemental Fig. S6). As for the aromatic resonances, the ribose H1′C1′ resonances corresponding to the internal loop nucleotides show the strongest shifts. In contrast to the aromatics, the lower part of the nonaloop (G745, A746, and U753) showed also clear effects. We interpret this as a second binding event in the lower part of the nonaloop.

FIGURE 9.

(A) Determination of estimated KD via ligand-detected 1H-1D NMR titration. (B) RNA-based Euclidean distance plot to determine the binding site of P6E06 to s2m Delta. The structural formula of the ligand is shown in the middle. Internal loop residues are highlighted in green and loop residues are highlighted in magenta. A threshold of twofold the standard deviation was used. (C) 1H, 13C HSQC spectra of the aromatic region of s2m (100 µM) with 0 µM (black) and 500 µM (yellow) P6E06. Resonance assignments are annotated and the notation of nucleotides corresponds to the position in the genome −29,000. Loop resonances are labeled in magenta and internal loop resonances are labeled in green. (D) The secondary structure of s2m Delta is colored with HSQC-based CSP heatmap (strong: red, weak: blue), and red corresponds to the maximum CSP detected.

DISCUSSION

Understanding the structure and function of UTRs in viruses is an important step in understanding the virus because these regions are known to fulfill regulatory roles (Yang and Leibowitz 2015). The s2m element is of particular interest due to its high degree of conservation and potential ability to be transferred horizontally between different viruses (Tengs et al. 2013; Tengs and Jonassen 2016; Colson et al. 2022). It is important to understand the structure and function of elements like s2m considering future pandemics or viral outbreaks, because it is likely that these viruses also contain similar motifs.

As of November 2023, there are more than 1000 structures deposited in pdb containing the main protease nsp5 and more than 1500 structures deposited in pdb containing Spike and its variants of concern (RCSB.org; Berman 2000). By stark contrast, empirical structural studies delineating the impact of mutations on the structure and dynamics of conserved RNA elements are very sparse. We focus on the 3D structure determination of these viral RNAs (Vögele et al. 2023; S Toews, A Wacker, EM Faison, et al., unpubl.; J Vögele, E Duchardt-Ferner, J Kaur Bains, et al., unpubl.) and report here on the detailed characterization of the impact of the Delta mutation in the s2m RNA element located in the 3′-UTR. This element stands out as it is one of the few viral elements for which a crystal structure was published for SCoV-1. To our knowledge, there is no experimental RNA structure available for SCoV-2 s2m. It has been shown by our laboratory that the secondary structure of s2m significantly differs between SCoV-1 and SCoV-2 (Wacker et al. 2020). Therefore, computational data that uses SCoV-1 as a starting point could potentially lead to a false conclusion. In addition, any biochemical experimental data that rely on the secondary structure of SCoV-1 will inevitably lead to wrong conclusions.

The secondary structure presented here for the Delta variant of s2m analyzes the impact of the G29742U mutation appearing in the Delta variant. In CD melting experiments, we detected a significantly higher melting temperature of s2m Delta (62°C) compared to SCoV-2 (55°C) or SCoV-1 (51°C). These results regarding the stability of the s2m Delta are in agreement with UV thermal denaturing experiments published by others (Cunningham et al. 2023).

In line with the increase in melting temperature, we detected an additional U29742–A29756 base pair in NOESY spectra in contrast to the internal unstable G-A mismatch that is present in SCoV-2. With this new base pair, an uninterrupted 6-bp upper helix is formed that likely leads to a global stabilization against thermal denaturation. With a complete imino proton assignment of the upper stem, we unambiguously show that s2m consists of two stems separated by a 10-nt asymmetric internal loop with a large apical nonaloop. In addition, as indicated by higher R1 rates and higher hetNOE values for the unpaired regions our dynamic NMR data confirm this secondary structure.

Previously, partial NOESY data of s2m Delta recorded at 292 K, at lower magnetic fields, with lower sample concentration and in a different buffer system were reported (Cunningham et al. 2023). The imino proton assignment reported there is incomplete and was not augmented by substantial assignment experiments, including 4D NOESY as reported here. Incomplete NMR data for an RNA can lead to ambiguous assignments, as is likely the case in the previous report. The reason for this may likely stem from the lower chemical shift resolution and fewer NOE cross peaks due to lower signal-to-noise compared to our spectra (Cunningham et al. 2023). These ambiguities, however, do not lead to a wrong secondary structure. In fact, follow-up MD simulations are in agreement with our dynamic NMR data (Makowski et al. 2023).

To characterize an NMR structure at a single-residue level, and to evaluate NMR dynamics data or map binding sites of an RNA, it is essential to assign as many resonances as possible. NMR resonance assignments of large RNAs are inherently challenging because of signal overlap, increased line widths, and intermediate exchange. In the case of s2m, in addition, the palindromic sequences flanking the 10-nt internal loop make a close-to-complete assignment difficult to achieve. We here present an assignment strategy using a 4D-HMQC-NOESY-HMQC published before (Stanek et al. 2013) in combination with {13C, 15N}-filtered NOESY and 3D TOCSY of selectively labeled samples. Even with severe signal overlap in 1H, 13C HSQC spectra, especially in the ribose regions, assigning resonances is enabled by separate assignment of the 1H and 13C chemical shifts using a combination of the mentioned experiments. More than 90% of the relevant NMR signals were assigned in this manner.

Based on the 13C assignment, we calculated canonical coordinates to analyze the ribose conformation of each nucleotide. For larger RNAs this is of particular interest as it is often challenging to determine torsion angles based on J-coupling constants, cross-correlated relaxation (CCR) rates, or chemical shift anisotropy (CSA) (Marino et al. 1996; Rinnenthal et al. 2007; Nozinovic et al. 2010).

Folded RNAs often show conformational dynamics, and especially loop or internal loop regions tend to be flexible. Already for small tetraloops dynamic data show some degree of flexibility and an ensemble is required to correctly describe the RNA structure (Oxenfarth et al. 2023). For larger RNAs containing larger unpaired regions, this is even more relevant. To quantify the dynamics in s2m, we conducted 1H, 13C HSQC-based T1, and hetNOE data of the aromatic H6C6/H8C8 and ribose H1′C1′ resonances that clearly confirm the flexibility of both unstructured regions, whereas the tip of the nonaloop shows the biggest effects. By comparing the hetNOE and T1 values within the RNA, we also concluded that the dynamics of the internal loop nucleotides occur on slower timescales than those of the loop nucleotides, and express overall less flexibility. Judging from the overall high degree of flexibility of this RNA, we conclude that a single structure is not sufficient to describe this motif and that an ensemble of structures is required to correctly describe s2m.

In the recent years, more and more different RNA drug targets have been identified (Warner et al. 2018; Campagne et al. 2019; Meyer et al. 2020; Kelly et al. 2021; Umuhire Juru and Hargrove 2021). Considering the regulatory roles of the UTRs of viruses, it is interesting to explore the druggability of these regions. Performing initial screens with small molecules can be the starting point for the development of new antiviral drugs. Except for classical intercalators, typical RNA–small molecule interactions involve conformationally flexible RNA regions with elevated dynamics. Ligand binding is often characterized by conformational adaption of these RNA motifs during the recognition and binding process (Noeske et al. 2006; Stelzer et al. 2011; Hermann 2016; Zafferani et al. 2021). We have shown here that seven out of the 10 hits identified in our previous work (Sreeramulu et al. 2021) also bind to s2m Delta. The two best binders show an estimated KD of <200 µM. Mapping of the largest binding-induced changes to individual RNA resonances confirmed the regions of s2m with the most pronounced hetNOE- and T1-derived dynamics as binding sites: the 10-nt dynamic internal loop and the apical nonaloop. It has been shown before that flexible regions of RNAs like the internal loop or the apical nonaloop of s2m can provide specific binding sites for small molecules (Stelzer et al. 2011). We assume, therefore, that especially the internal loop of s2m provides a perfect balance between flexibility and rigidity to facilitate specific binding events.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

DNA templates

Plasmids were used as DNA templates for in vitro transcription containing the different s2m RNA sequences from the SCoV-2 RNA genome. For 3′-end homogeneity, the HDV ribozyme sequence was positioned at the 3′-end of the s2m sequence (Ferre-D'Amare and Doudna 1996). This ribozyme induces self-cleavage at the 3′-end resulting in a cyclic phosphate. The production of the DNA plasmids with T7 promoter was done via hybridization of complementary oligonucleotides and ligation into the EcoRI and NcoI sites in the pSP64 vector (Promega) containing the HDV ribozyme (the s2m SCoV-2 plasmid was provided by the group of Prof. Dr. Julia Weigand as part of the COVID-NMR Consortium). For RNA production DNA plasmids containing the cloned sequence were transformed and amplified in Escherichia coli DH5α competent cells in SB medium. Purification of plasmids was performed using the Gigaprep (QIAGEN) purification kit with yields between 2 and 10 mg plasmid per liter SB medium. Plasmids were linearized with HindIII before being used for in vitro transcription. S2m RNA sequences are summarized in Supplemental Table S3 and plasmid vector cards can be obtained upon request.

In vitro transcription

RNA synthesis was done with in-house expressed and purified T7-polymerase in in vitro transcriptions. Preparative-scale in vitro transcriptions (10–15 mL) were performed. Nucleotides (13C, 15N labeled or natural abundance) were purchased at Silantes GmbH and used according to different isotope labeling schemes. All prepared RNA constructs and the yields after purification are listed in Supplemental Table S5.

Purification

Preparative-scale in vitro transcriptions were terminated after incubation for 6 h at 37°C by the addition of ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) with a final concentration of 80 mM at pH 8.0. Precipitation was done via the addition of 0.3 M (final concentration) NaOAc and isopropanol. RNA was isolated by performing gel electrophoresis to separate RNA bands. The respective RNA band was excised with a scalpel under UV illumination at 254 nm. RNA was eluted from gel pieces by diffusion into 0.3 M NaOAc solution. Eluted RNA was precipitated with EtOH and residual PAA was removed by reversed-phase HPLC using a Kromasil RP 18 column and a gradient of 0%–40% 0.1 M acetonitrile/triethylammonium acetate. RNA-containing fractions were freeze-dried and precipitated with LiOCl4 solution (2% in acetone) to exchange cations. Folding of RNA was achieved by heating for 5 min to 95°C and cooling to room temperature before exchanging to NMR buffer (25 mM K2HPO4/KH2PO4, pH 6.2, 50 mM KCl) via centrifugal concentrators with molecular mass cutoff of 2–3 kDa. The purity of RNA samples was verified through analytical denaturing PAGE. Special care was taken to verify the monomeric state and homogeneity of the RNA samples as others have reported kissing dimer and duplex formation of s2m Delta (Cunningham et al. 2023). After folding and rebuffering, the monomeric fold was verified by native PAGE (Supplemental Fig. S7).

CD

Stability differences between different construct variants were investigated by CD melting experiments on a spectropolarimeter (Jasco AKS J-810). Eight micromolars of RNA were measured in 25 mM potassium phosphate buffer with a pH of 6.2. A quartz cuvette with a path length of 1 mm was used. Melting curves were recorded at a wavelength of 261 nm from 15°C to 95°C and a heating rate of 1°C/min. All melting curves were measured from low to high temperature (forward) and from high to low temperature (reverse). Melting points were determined graphically via the intersection of the forward curve and the median of linearly fitted baselines.

NMR experiments

A summary of all measured NMR spectra for the resonance assignment of s2m Delta is given in Supplemental Table S5. Spectrometers that were used to record NMR spectra were 600-, 800-, 900-, and 950-MHz Bruker Avance NMR-spectrometers equipped with 5-mm cryogenic triple resonance TCI-N probes, a 700-MHz spectrometer that was equipped with a QCI-31P probe, and another 800-MHz spectrometer that was equipped with a TXO cryogenic probe. Sample specifications varied, but for exchangeable protons, measurements were performed in 5% D2O/95% H2O and for nonexchangeable protons in 100% D2O. All samples were measured in 5-mm Shigemi tubes in 25 mM K2HPO4/KH2PO4, at pH 6.2 and 50 mM KCl with sodium 2,2-dimethyl-2-silapentane-5-sulfonate (DSS) as an external reference. NMR spectra were analyzed using TopSpin 4.1, and resonance assignment was done with NMRFAM-SPARKY (Lee et al. 2015). HetNOE data were recorded to analyze structural dynamics at 308 K and evaluated via peak heights in Sparky.

Canonical coordinates

Canonical coordinates (can1* and can2*) were calculated based on 13C ribose chemical shifts as published before (Ebrahimi et al. 2001; Cherepanov et al. 2010):

where δ is 13C the chemical shift in ppm with indices for the ribose carbon, P is the pseudorotation phase, and γ the torsion angle.

T1 measurements

R1 rates were measured via an HSQC-based experiment as pseudo 3D using eight different T1 delays ranging from 20 msec to 1.5 sec at constant time with constant time delays of 12.5 msec (aromatics) and 8.8 msec (riboses) and with a relaxation delay of 2.6 sec. Errors were calculated based on the fitting with NMRFAM-SPARKY (Lee et al. 2015). For optimized spectral quality all experiments were recorded at 308 K.

HetNOE measurements

Heteronuclear NOE experiments were performed as pseudo-3D experiments measuring the NOE and the reference experiment without NOE in an interleaved manner with an interscan delay of 5 sec. For the NOE experiment, 3 sec presaturation were used, and an off-resonant pulse at −1000 ppm was used for temperature compensation in the reference experiment. Errors were calculated based on the signal/noise ratios. To decrease spectral overlap, two selectively 13C, 15N labeled samples were used (AC labeled: 290 µM, GU labeled: 360 µM). All measurements were carried out at 308 K and 800 MHz in 25 mM potassium phosphate (pH 6.2), 50 mM KCl, in 100% D2O.

Ligand binding measurements

For the determination of the estimated KD individual samples with varying RNA concentrations of RNA (50–250 µM) and constant ligand concentration (100 µM) were measured in 1.7-mm tubes. 1H-1D spectra were recorded and the chemical shifts of reporter signals of the ligands were monitored. values were fitted with Origin (OriginLab Corporation) based on Michaelis Menten kinetics. All samples were measured in 25 mM potassium phosphate (pH 6.2), 50 mM KCl, and 5% DMSO-d6. DSS was used as an internal reference. The binding site was determined in 1H, 13C HSQC experiments with 100 µM RNA and 0 or 500 µM ligand. Chemical shift changes were monitored and Euclidean distances (d) were determined via

where δ is the chemical shift change of 1H and 13C in ppm and α is the weighting factor for 13C based on the ratio of gyromagnetic ratios (α = 0.25) as described by the Al-Hashimi laboratory (Getz et al. 2007).

DATA DEPOSITION

Assignment data can be found in the BMRB (bmrb.io) with the code 52215.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Supplemental material is available for this article.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Work was supported by the Goethe Corona Funds, German funding agency (DFG) in Collaborative Research Center 902: “Molecular principles of RNA-based regulation,” and in SCHW 701/27-1 (495006306), and by European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation program iNEXT-discovery. Work at BMRZ was supported by the state of Hesse.

Footnotes

Article is online at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.079902.123.

Freely available online through the RNA Open Access option.

MEET THE FIRST AUTHORS

Tobias Matzel.

Maria Wirtz Martin.

Meet the First Author(s) is an editorial feature within RNA, in which the first author(s) of research-based papers in each issue have the opportunity to introduce themselves and their work to readers of RNA and the RNA research community. Tobias Matzel and Maria Wirtz Martin are co-first authors of this paper, “NMR characterization and ligand binding site of the stem–loop 2 motif from the Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2”. Tobias and Maria are, respectively, fifth-year and fourth-year PhD students in the Department of Organic Chemistry and Chemical Biology at Goethe University Frankfurt, in the group of Professor Harald Schwalbe. Tobias’ focus is using NMR spectroscopy to gain information about the structure, dynamics, and interactions of RNAs with other biomolecules or small molecules. Maria's focus is on researching RNA structure and dynamics of viral and bacterial RNA (riboswitches) with NMR spectroscopy, while also analyzing fragment-based screening data using NMR spectroscopy.

What are the major results described in your paper and how do they impact this branch of the field?

We were able to unambiguously assign >90% of all structurally relevant NMR resonances for the 45-nt stem–loop II motif (s2m) from SARS-CoV-2 Delta. In the course of this, we could clarify that s2m consists of two stems separated by a large internal loop and a highly dynamic nonaloop. With the assignment at hand, we were able to monitor these dynamics via heteronuclear NOE and T1 measurements. Additionally, we investigated ligand interactions and mapped the ligand binding site on s2m using the assigned 13C-HSQC spectra. This is particularly important as binding site mapping on most other resonances is restricted to base-paired regions due to solvent exchange of nucleotides in unpaired regions. Interestingly, ligand binding predominantly occurs at the internal loop of s2m.

What led you to study RNA or this aspect of RNA science?

MWM: My parents are scientists and I have always been interested in chemistry and biology, which is why I studied biochemistry. During my bachelor's thesis, I researched a protein with solid-state NMR and really enjoyed working in this field. For my master's thesis, I conducted research on riboswitches in the group of Professor Harald Schwalbe. RNA research using NMR piqued my interest because, unlike proteins, the tools and methods are not as advanced, presenting unique and intriguing challenges.

TM: During my master's studies in Frankfurt, I focused on NMR, as this has always interested me. Fortunately, Frankfurt offers access to several high-field NMR spectrometers and a lot of expertise in this field. Beginning with my master's thesis in the Schwalbe group, I investigated RNA–protein interactions with the protein side as the readout. Although I enjoyed my initial projects, I recognized the need to expand my knowledge of NMR on RNA. This method is particularly effective in this field as RNAs often contain highly dynamic regions that can only be correctly described when structural investigations are conducted in solution.

During the course of these experiments, were there any surprising results or particular difficulties that altered your thinking and subsequent focus?

At the beginning of the project, our focus was the Wuhan version of s2m. However, we quickly realized that a 13C assignment for this construct would be challenging due to the poor spectral quality, especially for the ribose resonances. With the Delta variant, we had a construct that appeared promising from the start. We were confident that we could achieve a close-to-complete assignment. Although we hoped that at some point we would be able to calculate a 3D structure, we soon realized the signal overlap was too severe even with this construct. Furthermore, we believe that especially the internal loop makes this RNA too dynamic to yield a tight bundle in structure calculations. Any single structure obtained for this RNA will not represent the true conformational space of s2m (in vivo). Instead, we followed up on our screening project and used the assignment of s2m to map the binding site of our small molecule hits using resonances of nonexchangeable protons. We found a correlation between our binding site mapping and our dynamic NMR data, which is one of our main claims for this manuscript.

What are some of the landmark moments that provoked your interest in science or your development as a scientist?

TM: Already during my primary school years, I developed a keen interest in science documentaries. In the following years, the people that influenced me the most were my biology, chemistry, and physics teachers. One particular incident that stands out was when my chemistry teacher moved me to the front row due to my disruptive behavior with my friends. Before that day I was mainly interested in biology and was not really good at chemistry. But when I sat there alone with no disturbance, I started to really follow the class. From that point on, I realized that chemistry was remarkably interesting, and my grades in chemistry, math, and physics improved significantly. An internship in another group from the Goethe University led to the decision to study chemistry with the possibility to specialize in biochemistry.

If you were able to give one piece of advice to your younger self, what would that be?

MWM: Reflecting on my past experiences, there are several pieces of advice that I would give to my younger self, that would have made my studies less stressful: Surround yourself with work and people that really interest you, and do not let failures get to you that easily. Establish a healthy work–life balance. Learn to deal with frustration. Be more confident in your results and present them with conviction. These lessons still remain relevant even for my current PhD journey.

What were the strongest aspects of your collaboration as co-first authors?

When we started this project during the COVID-19 pandemic, we had a work shifts system in our laboratory. Working in a team allowed for a smooth transition between the different shifts. Even after returning to normal operations, having a second person deeply involved in the project proved to be highly beneficial for exchanging opinions, finding solutions, or simply not being alone with our problems if things were not going as planned. Additionally, when the project branched off into smaller subprojects, we could distribute tasks and work on them simultaneously. Overall, the collaboration led to faster progress in the project, more thorough troubleshooting, and better interpretation of results.

REFERENCES

- Berg H, Wirtz Martin M, Altincekic N, Alshamleh I, Kaur Bains J, Blechar J, Ceylan B, de Jesus V, Dhamotharan K, Fuks C, et al. 2022. Comprehensive fragment screening of the SARS-CoV-2 proteome explores novel chemical space for drug development. Angew Chem Int Ed 61: e202205858. 10.1002/anie.202205858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman HM. 2000. The protein data bank. Nucleic Acids Res 28: 235–242. 10.1093/nar/28.1.235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campagne S, Boigner S, Rüdisser S, Moursy A, Gillioz L, Knörlein A, Hall J, Ratni H, Cléry A, Allain FH-T. 2019. Structural basis of a small molecule targeting RNA for a specific splicing correction. Nat Chem Biol 15: 1191–1198. 10.1038/s41589-019-0384-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantrelle F-X, Boll E, Brier L, Moschidi D, Belouzard S, Landry V, Leroux F, Dewitte F, Landrieu I, Dubuisson J, et al. 2021. NMR spectroscopy of the main protease of SARS-CoV-2 and fragment-based screening identify three protein hotspots and an antiviral fragment. Angew Chem Int Ed 60: 25428–25435. 10.1002/anie.202109965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherepanov AV, Glaubitz C, Schwalbe H. 2010. High-resolution studies of uniformly 13C, 15N-labeled RNA by solid-state NMR spectroscopy. Angew Chem Int Ed 49: 4747–4750. 10.1002/anie.200906885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colson P, Delerce J, Marion-Paris E, Lagier JC, Levasseur A, Fournier PE, La Scola B, Raoult D. 2022. A 21L/BA.2-21K/BA.1 “MixOmicron” SARS-CoV-2 hybrid undetected by qPCR that screen for variant in routine diagnosis. Infect Genet Evol 105: 105360. 10.1016/j.meegid.2022.105360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham CL, Frye CJ, Makowski JA, Kensinger AH, Shine M, Milback EJ, Lackey PE, Evanseck JD, Mihailescu M-R. 2023. Effect of the SARS-CoV-2 Delta-associated G15U mutation on the s2m element dimerization and its interactions with miR-1307-3p. RNA 29: 1754–1771. 10.1261/rna.079627.123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchardt-Ferner E, Ferner J, Fürtig B, Hengesbach M, Richter C, Schlundt A, Sreeramulu S, Wacker A, Weigand JE, Wirmer-Bartoschek J, et al. 2023. The COVID19-NMR consortium: a public report on the impact of this new global collaboration. Angew Chem Int Ed 62: e202217171. 10.1002/anie.202217171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebrahimi M, Rossi P, Rogers C, Harbison GS. 2001. Dependence of 13C NMR chemical shifts on conformations of RNA nucleosides and nucleotides. J Magn Reson 150: 1–9. 10.1006/jmre.2001.2314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferre-D'Amare AR, Doudna JA. 1996. Use of cis- and trans-ribozymes to remove 5′ and 3′ heterogeneities from milligrams of in vitro transcribed RNA. Nucleic Acids Res 24: 977–978. 10.1093/nar/24.5.977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frye CJ, Shine M, Makowski JA, Kensinger AH, Cunningham CL, Milback EJ, Evanseck JD, Lackey PE, Mihailescu MR. 2023. Bioinformatics analysis of the s2m mutations within the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron lineages. J Med Virol 95: e28141. 10.1002/jmv.28141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fürtig B, Richter C, Wöhnert J, Schwalbe H. 2003. NMR spectroscopy of RNA. Chembiochem 4: 936–962. 10.1002/cbic.200300700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Getz MM, Andrews AJ, Fierke CA, Al-Hashimi HM. 2007. Structural plasticity and Mg2+ binding properties of RNase P P4 from combined analysis of NMR residual dipolar couplings and motionally decoupled spin relaxation. RNA 13: 251–266. 10.1261/rna.264207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert C, Tengs T. 2021. No species-level losses of s2m suggests critical role in replication of SARS-related coronaviruses. Sci Rep 11: 1–5. 10.1038/s41598-021-95496-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser SJ, Schwalbe H, Marino JP, Griesinger C. 1996. Directed TOCSY, a method for selection of directed correlations by optimal combinations of isotropic and longitudinal mixing. J Magn Reson B 112: 160–180. 10.1006/jmrb.1996.0126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goebel SJ, Miller TB, Bennett CJ, Bernard KA, Masters PS. 2007. A hypervariable region within the 3′ cis-acting element of the murine coronavirus genome is nonessential for RNA synthesis but affects pathogenesis. J Virol 81: 1274–1287. 10.1128/JVI.00803-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Günther S, Reinke PYA, Fernández-García Y, Lieske J, Lane TJ, Ginn HM, Koua FHM, Ehrt C, Ewert W, Oberthuer D, et al. 2021. X-ray screening identifies active site and allosteric inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 main protease. Science 372: 642–646. 10.1126/science.abf7945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann T. 2016. Small molecules targeting viral RNA. WIREs RNA 7: 726–743. 10.1002/wrna.1373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imperatore JA, Cunningham CL, Pellegrene KA, Brinson RG, Marino JP, Evanseck JD, Mihailescu MR. 2022. Highly conserved s2m element of SARS-CoV-2 dimerizes via a kissing complex and interacts with host miRNA-1307-3p. Nucleic Acids Res 50: 1017–1032. 10.1093/nar/gkab1226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H, Joshi A, Gan T, Janowski AB, Fujii C, Bricker TL, Darling TL, Harastani HH, Seehra K, Chen H, et al. 2023. The highly conserved stem-loop II motif is dispensable for SARS-CoV-2. J Virol 97: e0063523. 10.1128/jvi.00635-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly ML, Chu C-C, Shi H, Ganser LR, Bogerd HP, Huynh K, Hou Y, Cullen BR, Al-Hashimi HM. 2021. Understanding the characteristics of nonspecific binding of drug-like compounds to canonical stem–loop RNAs and their implications for functional cellular assays. RNA 27: 12–26. 10.1261/rna.076257.120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kensinger AH, Makowski JA, Pellegrene KA, Imperatore JA, Cunningham CL, Frye CJ, Lackey PE, Mihailescu MR, Evanseck JD. 2023. Structural, dynamical, and entropic differences between SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 s2m elements using molecular dynamics simulations. ACS Phys Chem Au 3: 30–43. 10.1021/acsphyschemau.2c00032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kofstad T, Jonassen CM. 2011. Screening of feral and wood pigeons for viruses harbouring a conserved mobile viral element: characterization of novel astroviruses and picornaviruses. PLoS ONE 6: e25964. 10.1371/journal.pone.0025964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee W, Tonelli M, Markley JL. 2015. NMRFAM-SPARKY: enhanced software for biomolecular NMR spectroscopy. Bioinformatics 31: 1325–1327. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Sczepanski JT. 2022. Targeting a conserved structural element from the SARS-CoV-2 genome using l-DNA aptamers. RSC Chem Biol 3: 79–84. 10.1039/d1cb00172h [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lulla V, Wandel MP, Bandyra KJ, Ulferts R, Wu M, Dendooven T, Yang X, Doyle N, Oerum S, Beale R, et al. 2021. Targeting the conserved stem loop 2 motif in the SARS-CoV-2 genome. J Virol 95: e0066321. 10.1128/JVI.00663-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macchiagodena M, Pagliai M, Procacci P. 2020. Identification of potential binders of the main protease 3CLpro of the COVID-19 via structure-based ligand design and molecular modeling. Chem Phys Lett 750: 137489. 10.1016/j.cplett.2020.137489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makowski JA, Kensinger AH, Cunningham CL, Frye CJ, Shine M, Lackey PE, Mihailescu MR, Evanseck JD. 2023. Delta SARS-CoV-2 s2m structure, dynamics, and entropy: consequences of the G15U mutation. ACS Phys Chem Au 3: 434–443. 10.1021/acsphyschemau.3c00008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manfredonia I, Nithin C, Ponce-Salvatierra A, Ghosh P, Wirecki TK, Marinus T, Ogando NS, Snijder EJ, van Hemert MJ, Bujnicki JM, et al. 2020. Genome-wide mapping of SARS-CoV-2 RNA structures identifies therapeutically-relevant elements. Nucleic Acids Res 48: 12436–12452. 10.1093/nar/gkaa1053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marino JP, Schwalbe H, Glaser SJ, Griesinger C. 1996. Determination of γ and stereospecific assignment of H5′ protons by measurement of 2J and 3J coupling constants in uniformly 13C labeled RNA. J Am Chem Soc 118: 4388–4395. 10.1021/ja953554o [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer SM, Williams CC, Akahori Y, Tanaka T, Aikawa H, Tong Y, Childs-Disney JL, Disney MD. 2020. Small molecule recognition of disease-relevant RNA structures. Chem Soc Rev 49: 7167–7199. 10.1039/D0CS00560F [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monceyron C, Grinde B, Jonassen TØ. 1997. Molecular characterisation of the 3′-end of the astrovirus genome. Arch Virol 142: 699–706. 10.1007/s007050050112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noeske J, Buck J, Furtig B, Nasiri HR, Schwalbe H, Wohnert J. 2006. Interplay of “induced fit” and preorganization in the ligand induced folding of the aptamer domain of the guanine binding riboswitch. Nucleic Acids Res 35: 572–583. 10.1093/nar/gkl1094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nozinovic S, Richter C, Rinnenthal J, Fürtig B, Duchardt-Ferner E, Weigand JE, Schwalbe H. 2010. Quantitative 2D and 3D Γ-HCP experiments for the determination of the angles α and ζ in the phosphodiester backbone of oligonucleotides. J Am Chem Soc 132: 10318–10329. 10.1021/ja910015n [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otting G, Wüthrich K. 1989. Extended heteronuclear editing of 2D 1H NMR spectra of isotope-labeled proteins, using the X(ω1, ω2) double half filter. J Magn Reson 85: 586–594. 10.1016/0022-2364(89)90249-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oxenfarth A, Kümmerer F, Bottaro S, Schnieders R, Pinter G, Jonker HRA, Fürtig B, Richter C, Blackledge M, Lindorff-Larsen K, et al. 2023. Integrated NMR/molecular dynamics determination of the ensemble conformation of a thermodynamically stable CUUG RNA tetraloop. J Am Chem Soc 145: 16557–16572. 10.1021/jacs.3c03578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padroni G, Bikaki M, Novakovic M, Wolter AC, Rüdisser SH, Gossert AD, Leitner A, Allain FH-T. 2023. A hybrid structure determination approach to investigate the druggability of the nucleocapsid protein of SARS-CoV-2. Nucleic Acids Res 51: 4555–4571. 10.1093/nar/gkad195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rangan R, Zheludev IN, Hagey RJ, Pham EA, Wayment-Steele HK, Glenn JS, Das R. 2020. RNA genome conservation and secondary structure in SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-related viruses: a first look. RNA 26: 937–959. 10.1261/rna.076141.120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rangan R, Watkins AM, Chacon J, Kretsch R, Kladwang W, Zheludev IN, Townley J, Rynge M, Thain G, Das R. 2021. De novo 3D models of SARS-CoV-2 RNA elements from consensus experimental secondary structures. Nucleic Acids Res 49: 3092–3108. 10.1093/nar/gkab119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinnenthal J, Richter C, Ferner J, Duchardt E, Schwalbe H. 2007. Quantitative Γ-HCNCH: determination of the glycosidic torsion angle χ in RNA oligonucleotides from the analysis of CH dipolar cross-correlated relaxation by solution NMR spectroscopy. J Biomol NMR 39: 17–29. 10.1007/s10858-007-9167-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson MP, Igel H, Baertsch R, Haussler D, Ares M, Scott WG. 2005. The structure of a rigorously conserved RNA element within the SARS virus genome. PLoS Biol 3: e5. 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryder SP, Morgan BR, Coskun P, Antkowiak K, Massi F. 2021. Analysis of emerging variants in structured regions of the SARS-CoV-2 genome. Evol Bioinform Online 17: 117693432110141. 10.1177/11769343211014167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwalbe H, Marino JP, Glaser SJ, Griesinger C. 1995. Measurement of H,H-coupling constants associated with .nu.1, .nu. 2, and .nu.3 in uniformly 13C-labeled RNA by HCC-TOCSY-CCH-E.COSY. J Am Chem Soc 117: 7251–7252. 10.1021/ja00132a028 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simba-Lahuasi A, Cantero-Camacho Á, Rosales R, McGovern BL, Rodríguez ML, Marchán V, White KM, García-Sastre A, Gallego J. 2022. SARS-CoV-2 inhibitors identified by phenotypic analysis of a collection of viral RNA-binding molecules. Pharmaceuticals 15: 1448. 10.3390/ph15121448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sreeramulu S, Richter C, Berg H, Wirtz Martin MA, Ceylan B, Matzel T, Adam J, Altincekic N, Azzaoui K, Bains JK, et al. 2021. Exploring the druggability of conserved RNA regulatory elements in the SARS-CoV-2 genome. Angew Chem Int Ed 60: 19191–19200. 10.1002/anie.202103693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanek J, Podbevšek P, Koźmiński W, Plavec J, Cevec M. 2013. 4D Non-uniformly sampled C,C-NOESY experiment for sequential assignment of 13C,15N-labeled RNAs. J Biomol NMR 57: 1–9. 10.1007/s10858-013-9771-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stelzer AC, Frank AT, Kratz JD, Swanson MD, Gonzalez-Hernandez MJ, Lee J, Andricioaei I, Markovitz DM, Al-Hashimi HM. 2011. Discovery of selective bioactive small molecules by targeting an RNA dynamic ensemble. Nat Chem Biol 7: 553–559. 10.1038/nchembio.596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tengs T, Jonassen C. 2016. Distribution and evolutionary history of the mobile genetic element s2m in coronaviruses. Diseases 4: 27. 10.3390/diseases4030027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tengs T, Kristoffersen AB, Bachvaroff TR, Jonassen CM. 2013. A mobile genetic element with unknown function found in distantly related viruses. Virol J 10: 132. 10.1186/1743-422X-10-132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umuhire Juru A, Hargrove AE. 2021. Frameworks for targeting RNA with small molecules. J Biol Chem 296: 100191. 10.1074/jbc.REV120.015203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vögele J, Hymon D, Martins J, Ferner J, Jonker HRA, Hargrove AE, Weigand JE, Wacker A, Schwalbe H, Wöhnert J, et al. 2023. High-resolution structure of stem-loop 4 from the 5′-UTR of SARS-CoV-2 solved by solution state NMR. Nucleic Acids Res 51: 11318–11331. 10.1093/nar/gkad762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wacker A, Weigand JE, Akabayov SR, Altincekic N, Bains JK, Banijamali E, Binas O, Castillo-Martinez J, Cetiner E, Ceylan B, et al. 2020. Secondary structure determination of conserved SARS-CoV-2 RNA elements by NMR spectroscopy. Nucleic Acids Res 48: 12415–12435. 10.1093/nar/gkaa1013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner KD, Hajdin CE, Weeks KM. 2018. Principles for targeting RNA with drug-like small molecules. Nat Rev Drug Discov 17: 547–558. 10.1038/nrd.2018.93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu F, Zhao S, Yu B, Chen Y-M, Wang W, Song Z-G, Hu Y, Tao Z-W, Tian J-H, Pei Y-Y, et al. 2020. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature 579: 265–269. 10.1038/s41586-020-2008-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang D, Leibowitz JL. 2015. The structure and functions of coronavirus genomic 3′ and 5′ ends. Virus Res 206: 120–133. 10.1016/j.virusres.2015.02.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zafferani M, Haddad C, Luo L, Davila-Calderon J, Chiu L-Y, Mugisha CS, Monaghan AG, Kennedy AA, Yesselman JD, Gifford RJ, et al. 2021. Amilorides inhibit SARS-CoV-2 replication in vitro by targeting RNA structures. Sci Adv 7: 6096. 10.1126/sciadv.abl6096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Lin D, Sun X, Curth U, Drosten C, Sauerhering L, Becker S, Rox K, Hilgenfeld R. 2020. Crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 main protease provides a basis for design of improved α-ketoamide inhibitors. Science 368: 409–412. 10.1126/science.abb3405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]