Abstract

Cartilage endplate (CEP) acts as a protective mechanical barrier for intervertebral discs (IVDs), yet its heterogeneous structure-function relationships are poorly understood. This study filled this gap by characterizing the regional biphasic mechanical properties and correlating them with regional biochemical composition in human lumbar CEP. Samples from central, lateral, anterior, and posterior portions of the disc (n=8/region) were mechanically tested under confined compression to quantify swelling pressure, equilibrium aggregate modulus, and hydraulic permeability. These properties were correlated with CEP porosity and glycosaminoglycan (s-GAG) content, which were obtained by biochemical assays of the same specimens. Both swelling pressure (142.79±85.89 kPa) and aggregate modulus (1864.10±1240.99 kPa) were found to be regionally dependent (p=0.0001 and p=0.0067, respectively) in the CEP and trended lowest in the central location. No significant regional dependence was observed for CEP permeability (1.35±0.97 *10−16 m4/Ns). Porosity measurements correlated significantly with swelling pressure (r=−0.40, p=0.0227), aggregate modulus (r=−0.49, p=0.0046), and permeability (r=0.36, p=0.0421), and appeared to be the primary indicator of CEP biphasic mechanical properties. Second harmonic generation microscopy also revealed regional patterns of collagen fiber anchoring, with fibers inserting the CEP perpendicularly in the central region and at off-axial directions in peripheral regions. These results suggest that CEP tissue has regionally dependent mechanical properties which are likely due to the regional variation in porosity and matrix structure. This work advances our understanding of healthy baseline endplate biomechanics and lays a groundwork for further understanding the role of CEP in IVD degeneration.

Keywords: Low back pain, Intervertebral disc, Cartilage endplate, Biomechanics

Introduction

Intervertebral discs (IVDs) in the lumbar spine are among the largest avascular tissues in the human body, crucial for weight bearing, shock absorption, and the coordination of complex three-dimensional motions (Adams and Roughley, 2006; Alonso and Hart, 2014). Each disc is interfaced with adjacent vertebrae via a thin layer of hyaline cartilage endplate (CEP) tissue covering its superior and inferior ends. CEP is considered vital for supplying nutrients to the disc and maintaining its mechanical integrity as it ages or degenerates (Urban et al., 1982; Roberts et al., 1989; Urban and Roberts, 1995; Adams and Roughley, 2006). Changes to CEP permeability during calcification for instance, has been implicated in the disruption of internal nutrient solute gradients critical for disc cell viability (Roberts et al., 1993, 1996; Soukane et al., 2007; Jackson et al., 2011; Wu et al., 2013; Huang et al., 2014). Other changes in the CEP, such as lesion formation, have been linked to heightened inflammatory responses in the disc and collagen matrix catabolism, leading to altered IVD kinematics and further injury (Lotz and Ulrich, 2006; Risbud and Shapiro, 2014; Dowdell et al., 2017).

The CEP has been previously characterized as having a greater compressive modulus and lower hydraulic permeability compared to other IVD regions in bovine tissue (Wu et al., 2015). In human, CEP aggregate modulus is nearly four times greater than that for NP tissue and up to thirteen times greater than that for the AF, while hydraulic permeability has been found to be up to an order of magnitude lower in the CEP than in the AF (Cortes et al., 2014; DeLucca et al., 2016). These findings have led to the general understanding that CEP tissue minimizes stress concentration at the IVD-bone interface, acting as a transition layer between the softer disc tissue and more rigid vertebral bone. Moreover, the lower CEP permeability has been hypothesized to support interstitial fluid pressurization within the disc, creating a barrier to fluid convection which may help the disc to better sustain compressive loads (Wu et al., 2015). This may be especially true of the bordering nucleus pulposus (NP) region at the center of the IVD, which is gel-like in structure and is densely embedded with electrically charged proteoglycan molecules that promote disc swelling (Buckwalter, 1995; Perie et al., 2006). In regions where the CEP makes contact with the AF, which is less hydrated and more organized in its matrix (Buckwalter, 1995), it may have additional roles in resisting tension and shear to prevent the AF from experiencing collagen fiber tears or herniation injury (Iatridis et al., 2005; Fields et al., 2018; Zhou et al., 2021).

Other characterizations of mechanical and solute transport properties in the CEP have further highlighted its uniqueness and material complexity in the IVD. Viscoelastic tensile properties have been measured in the CEP, with average equilibrium tensile moduli shown to be comparable to that of adult femoral articular cartilage (Fields et al., 2014). CEP hydraulic permeability has been found to decrease in value in degenerated IVD, while aggregate modulus stays at a similar magnitude (DeLucca et al., 2016). From our previous studies on nutrient solute (glucose), metabolite (lactate), and ion (Na+ and Cl−) diffusivities in the CEP, regionally dependent (i.e., central, lateral, anterior, and posterior) solute transport rates have been observed (Wu et al., 2016, 2017). Furthermore, qualitative differences in cartilage endplate histomorphology suggest a regionally distinct interface structure as well (Wu et al., 2016). However, region-dependent structure function relationships between CEP matrix structure, biochemical composition, and biphasic mechanical properties remain unclear.

Given the regional dependence in human CEP diffusion phenomena and its histological pattern (Wu et al., 2016, 2017), we hypothesized that CEP biphasic mechanical properties are variable between central, lateral, anterior, and posterior regions owing in part to unique tissue composition and structure. Therefore, the primary objectives of this study were to 1) spatially quantify biphasic properties from healthy human CEPs using a previously established confined compression technique; 2) correlate regionally obtained CEP biochemical compositions with biomechanical data from the same specimens; and 3) assess the CEP-bone interface morphology and disc collagen fiber insertion structure in each endplate region through label-free multiphoton confocal microscopy. This work aims to enhance current knowledge of healthy baseline CEP biomechanics and lay a groundwork for further understanding CEP heterogeneity and its biomechanical functions with disc degeneration progression.

Methods

Sample preparation

Six fresh frozen human cadaver spines [3 males, 3 females; 46.7±9.3 years of age] were obtained from a tissue bank (We Are Sharing Hope SC, Charleston, SC) under institutional approval by the Medical University of South Carolina. Gross-morphologic defects in the spines were assessed by our clinical collaborator (CR) using the Thompson grading scale (Thompson et al., 1990). Discs with grades greater than III or containing degeneration related defects (such as fissures and macrocalcification) were excluded from analysis. In total, twelve intervertebral discs were harvested across each of the L1-L5 vertebrae levels [1/12 (8.3%) from L1-2; 3/12 (25%) from L2-3; 3/12 (25%) from L3-4; 2/12 (16.7%) from L4-5, 1/12 (8.3%) from T12-L1, and 2/12 (16.7%) from L5-S1]. Segments were individually wrapped in plastic and gauze, which was soaked in a phosphate buffered saline solution (1xPBS, pH=7.4) to prevent dehydration (Yao et al., 2002). Discs were stored at −20°C for up to 48 hours prior to testing, as previous literature indicates this method of storage has negligible impacts on cartilaginous tissue mechanical properties (Hirsch and Galante, 1967; Smeathers and Joanes, 1988; Dhillon et al., 2001; Allen and Athanasiou, 2005).

Discs were opened using a sterile surgical scalpel. Cylindrical shaped osteochondral tissue plugs containing vertebral bone, CEP, and disc tissue, were harvested using a 5mm diameter corneal trephine from the central, lateral, anterior, and posterior regions of the discs (n=8/region; Fig. 1a). A freezing stage microtome (SM2400, Leica Microsystems GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany) was used to shave off underlying vertebral bone first, and then more transparent NP or AF tissue from the CEP (Fig. 1b). An embedded plastic spacer (0.7mm) served as a cutting reference to maintain the CEP thickness near its average in the human lumbar spine (Roberts et al., 1989). The prepared specimen thickness was assessed using a custom-designed current sensing digital micrometer (Gu et al., 2002; Yao et al., 2002). The thickness of the final cylindrically shaped CEP samples ranged from 0.5 – 0.8mm (average of 0.67mm), consistent with prior studies (Roberts et al., 1989; Wu et al., 2017, 2016, 2015).

Fig. 1.

(a) specimen regions, (b) schematic of sample preparation, (c) schematic of confined compression test chamber, and (d) mechanical testing protocol.

Biomechanical testing

Confined compression mechanical tests were performed in 1xPBS (pH=7.4) on a Thermal Advantage Dynamic Mechanical Analyzer (TA-Q800 DMA, New Castle, DE), following a previously established technique (Yao et al., 2002; Wu et al., 2015). The force and displacement measurement precisions of this instrument were 1mN and 1 μm respectively. CEP specimens were laterally confined in the testing chamber and compressed between a porous platen (20μm average pore size) and the DMA displacement probe (Fig. 1c), with the bony side of the CEP oriented toward the porous platen.

CEP specimens were situated first within the testing chamber, and then immersed in PBS, where they could swell freely in the axial direction. Samples were then compressed to 10% strain relative to their initial thickness measured prior to testing. This offset strain was to ensure interdigitation between the CEP and porous platen and to confine the specimen fully at its periphery. At this pre-strained height, stress relaxation was recorded in each sample, and the equilibrium swelling load (after approximately 1 hour) was used to calculate CEP swelling pressure. A creep test was then conducted by applying an additional load equal to 0.4 times the equilibrium swelling load. This protocol was chosen based on preliminary testing, to maintain resulting creep strains at approximately 3-5% after two hours of compression to satisfy the linear biphasic theory (Fig. 1d). Hydraulic permeability and equilibrium aggregate modulus were determined by curve fitting creep data to previously developed biphasic theory (Mow et al., 1980).

Biochemical analysis

Prior to mechanical testing (immediately after the initial thickness measurement), the wet weight of each CEP specimen was determined by weighing samples in air on an analytical balance. When testing was completed, specimens were again weighed while submerged in a 1xPBS solution using a density determination kit (Sartorius, Germany). This ensured accuracy in sample weights while minimizing tissue swelling between preparation and testing. Samples were then lyophilized, and a dry tissue weight was obtained. Following the procedure outlined in prior studies, Archimedes’ principle was used to determine the CEP volume fraction of water, or porosity () (Gu et al., 1996, 2002; Yao et al., 2002):

| (1) |

Where and denote the wet weight and dry specimen weights respectively, denotes the specimen weight measured in PBS solution, and is the relative density of the PBS solution to water (given to be 1.005). Lyophilized CEP tissues were then assayed for sulfated-glycosaminoglycan (s-GAG) content using a Blyscan™ Glycosaminoglycan (s-GAG) assay kit (Biocolor Life Science, Northern Ireland). This assay uses 1,9-dimethyl methylene blue dye binding to GAG molecules, with standards included in the kit.

Multiphoton microscopy

Four additional CEP plugs were prepared fresh from each region, cut into 0.5 mm thick blocks in the sagittal plane to reveal intact bone, endplate, and disc tissue components. In the lateral, anterior, and posterior CEP, slices were made perpendicular to the annulus lamellae to reveal its basic ring structure. These blocks were immersed in a petri dish containing PBS saline solution and lightly compressed against the glass bottom using a glass coverslip and custom 3D-printed clamp. Endplate interfaces were imaged over a 3x1mm area using an Olympus Fluoview 1200 laser scanning microscope with a 30x oil immersion objective lens (UPLSAPO, 30XSIR; Olympus). Images were taken as composites in two steps. First, collagen fibers were targeted fluorescently by second harmonic generation (SHG) using an excitation wavelength of 845nm, with emitted signal collected in the 420-460nm range (Coombs et al., 2017). Then, cell morphology and remaining extracellular matrix structures were visualized through two-photon excited fluorescence (2PEF) at 740nm excitation, measured in 575-630nm and 420-460nm ranges respectively (Coombs et al., 2017; Fan et al., 2023). Images were captured in mosaic fashion with a 1600x1200-pixel resolution and 480x360um field of view. Fiji ImageJ software (Schindelin et al., 2012) and the MIST plugin (Blattner et al., 2014; Chalfoun et al., 2017) were used to assemble them. The OrientationJ plugin (Rezakhaniha et al., 2012) was used to quantify the fiber orientation distribution in both CEP and adjacent disc fiber layers, from selected regions of interest matching the average CEP thickness in tested specimens.

Statistical analysis

Mechanical and biochemical measurements were analyzed for differences among CEP regions. Linear mixed effects models were fit to each outcome, considering error heterogeneity for region and donor as supported by likelihood-based model selection. Models were fit using the restricted maximum likelihood approach, implemented through the ‘nlme’ package (Pinheiro et al., 2023) in R (R Core Team, 2023). Regional dependence was assessed by Type III ANOVA tests. Contrasts were made between regions, designating the central endplate region as a reference, and using Bonferroni p-value adjustment to address multiplicity. Regional estimates were summarized by model-based averages and 95% confidence intervals (mean ± SD reported in Supp. Table 1). Additional models were constructed to compare the central CEP with a pooled grouping of peripheral (lateral, anterior, and posterior) CEP regions (Supp. Tables 2-3). Correlations between total biomechanical and biochemical measurements were reported using Pearson’s r. Findings were considered significant at the p<0.05 alpha level.

Results

Regionally mapped endplate biomechanical and biochemical properties

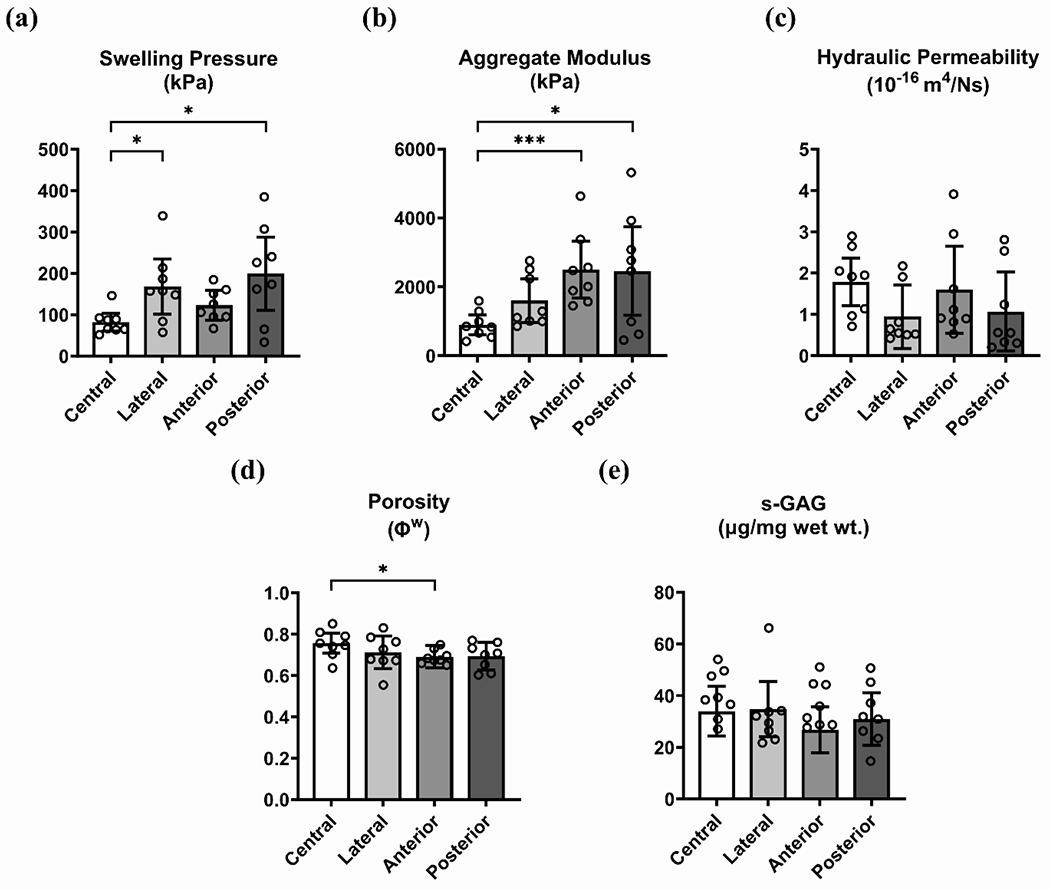

The CEP was observed to have regionally dependent swelling pressure (142.79 kPa, 95% CI [111.82, 173.76]; p=0.0067) and aggregate modulus (1864.10 [1416.67, 2311.52] kPa; p=0.0001). Swelling pressure was significantly greater in lateral (167.6 [101.0, 234.3] kPa; p=0.0234) and posterior CEP (198.8 [110.2, 287.4] kPa; p=0.0190) compared with central CEP (82.1 [60.4, 103.7] kPa) (Fig. 2a). It was also greater when compared for peripheral CEP (p=0.0001) in relation to central CEP (Supp. Fig. 1). Aggregate modulus (Fig. 2b) was greater in the anterior CEP (2501 [1672, 3331] kPa; p=0.0002) and posterior CEP (2458 [1176, 3740] kPa; p=0.0351) compared to central CEP (899 [613, 1185] kPa), and was likewise larger for peripheral CEP (p=0.0001; Supp. Fig. 1). Regional variation was not clear for permeability (1.35 [1.00, 1.70] *10−16 m4/Ns; p=0.1403), porosity (0.71 [0.69, 0.74]; p=0.1268), or s-GAG content (35.9 [31.9, 39.9] μg/mg wet wt.; p=0.1986), although pairwise comparisons indicated a lower porosity in the anterior CEP (0.69 [0.64, 0.75]; p=0.0367) relative to central CEP (0.76 [0.71, 0.80]). These effects were consistent with comparisons made between central and peripheral CEP (permeability: p=0.0912; porosity: p=0.0332; s-GAG: p=0.2077; Supp. Fig. 1).

Fig. 2.

Endplate biomechanical properties and composition by region: (a) swelling pressure, (b) aggregate modulus, (c) hydraulic permeability, (d) porosity, and (e) s-GAG content. Asterisks indicate differences at the given levels of statistical significance (* p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001, **** p<0.0001).

Relationships between endplate biomechanical properties and composition

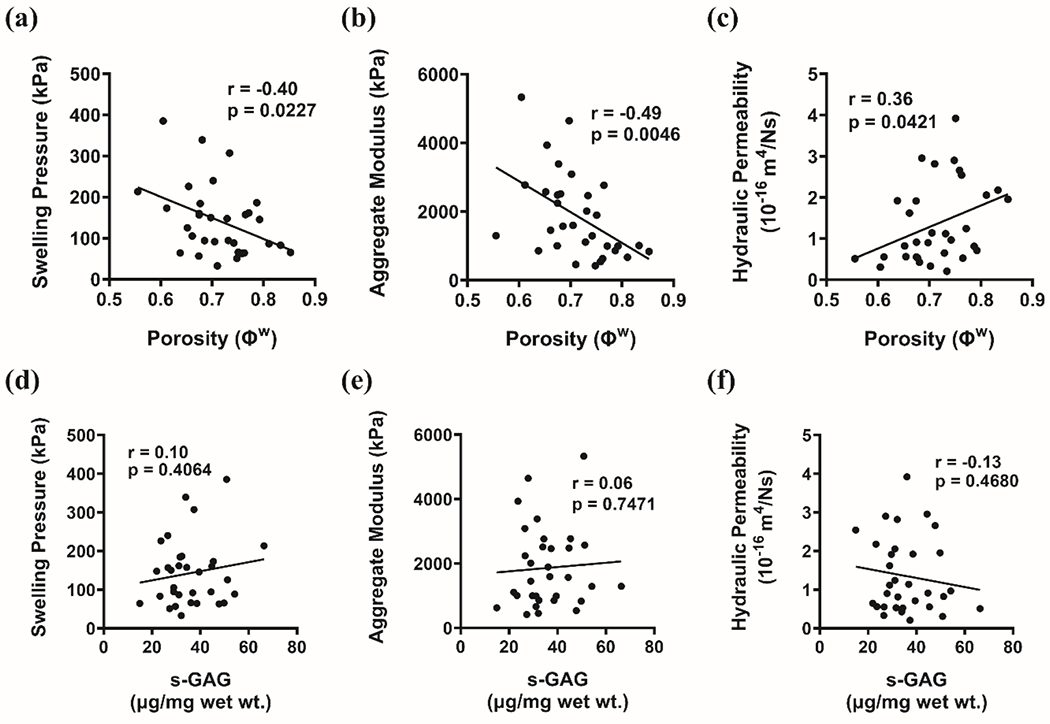

In Fig. 3, swelling pressure (r=−0.40, p=0.0227), aggregate modulus (r=−0.49, p=0.0046), and hydraulic permeability (r=0.36, p=0.0421) are shown to be significantly correlated with porosity. Strong positive correlation was additionally observed between swelling pressure and aggregate modulus (p=0.0001, r=0.69, Supp. Fig. 2). No significant correlation was observed between swelling pressure and s-GAG content (r=0.10, p=0.4064), aggregate modulus and s-GAG content (r=0.06, p=0.7471), or permeability and s-GAG content (r=−0.13, p=0.4680).

Fig. 3.

Correlations between endplate biomechanical outcomes and composition: swelling pressure, aggregate modulus, and hydraulic permeability vs. porosity (a)-(c) and vs. s-GAG content (d)-(f).

Endplate microscopy

Microscopy images (Fig. 4a-d) revealed a regionally unique endplate and disc transitional layer fiber structure. In the central region, fibers assumed a transverse orientation in the endplate, but were axially aligned in the disc transition layer (Fig. 4e). This region was absent of distinct fiber bundle formation in the disc, and there was no visible anchoring of disc fibers at the CEP-disc interface (Fig. 4a). The anterior and lateral regions were different, with endplate fibers that were more isotropic in orientation, and disc transitional layer fibers that inserted the endplate at off-axial directions (Fig. 4e). Fibers from the disc were seen to anchor into the endplate in distinct woven bundles (Fig. 4b-c). In the posterior region, endplate fibers were transversely oriented like the central region, but featured disc transition layer fibers that inserted the endplate in a slightly off-axial direction (Fig. 4d-e).

Fig. 4.

Multiphoton microscopy of the IVD interface: (a) central, (b) lateral, (c) anterior, and (d) posterior regions (SHG at 845nm [blue: 420-460nm collection range] and 2PEF at 740nm [green: 420-460nm range; red: 575-630nm range]; SHG also in grayscale). Regional fiber angle distributions (e) are quantified from CEP and transitional disc fiber layers.

Discussion

Osmotic swelling pressure, aggregate modulus, and hydraulic permeability were studied in healthy human cartilage endplate (CEP) and correlated with endplate porosity and sulfated glycosaminoglycan (s-GAG) content. The CEP exhibited higher equilibrium aggregate modulus and lower hydraulic permeability compared to other cartilaginous tissues (Table 1), supporting its role as a mechanical barrier crucial for maintaining fluid pressurization within the disc (Wu et al., 2015; DeLucca et al., 2016). This study found heterogeneous distributions of swelling pressure and aggregate modulus across the central, lateral, anterior, and posterior CEP regions, with the central region being less stiff than surrounding areas. Increased CEP stiffness toward peripheral regions may counteract unevenly distributed compression during daily activities, especially to resist greater magnitude stresses and strain exerted on the annulus fibrosus through bending (Adams et al., 1990; Tsantrizos et al., 2005; Ryan et al., 2008; Byrne et al., 2019). Greater compliance in the central CEP could relate to its pattern of axial bulging observed with nucleus pressurization (Lotz et al., 2013). Furthermore, previous mapping of vertebral endplate, the layer of bone beneath the CEP, has shown a mechanically weaker central region, prone to fracture under compression (Grant et al., 2001; Zhao et al., 2009; Fields et al., 2012). If the central CEP is also mechanically weak, there may be increased risk of disc protrusion into the vertebrae and the development of Modic changes in the subchondral bone (Dudli et al., 2016).

Table 1.

Biphasic properties (mean ± standard deviation) of CEP, other IVD tissues (NP and AF), and articular cartilage (AC).

| Water (%) | Aggregate Modulus (MPa) | Permeability (10−15 m4/Ns) | Method | Species | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 71.3±6.7 | 1.86±1.24 | 0.14±0.10 | Confined Compression | Human CEP Total | This study |

| 75.6±6.6 | 0.90±0.39 | 0.18±0.08 | Confined Compression | Human CEP Central | This study |

| 71.2±8.6 | 1.60±0.77 | 0.09±0.07 | Confined Compression | Human CEP Lateral | This study |

| 69.1±3.4 | 2.50±1.07 | 0.16±0.12 | Confined Compression | Human CEP Anterior | This study |

| 69.4±6.4 | 2.46±1.71 | 0.11±0.10 | Confined Compression | Human CEP Posterior | This study |

| 69.9±6.3 | 2.19±1.26 | 0.12±0.10 | Confined Compression | Human CEP Peripheral | This study |

| ~59.5 | ~0.26 | ~0.56 | Confined Compression | Human CEP Healthy | (DeLucca et al., 2016) |

| ~61.8 | ~0.24 | ~0.23 | Confined Compression | Human CEP Degenerated | (DeLucca et al., 2016) |

| 75.4±6.6 | 0.39±0.34 | 0.56±0.51 | Confined Compression | Human CEP | (Cortes et al., 2014) |

| 89.7±5.6 | 0.10±0.07 | 0.55±0.78 | Confined Compression | Human NP | (Cortes et al., 2014) |

| 81.4±4.3 | 0.03±0.02 | 6.40±7.60 | Confined Compression | Human AF | (Cortes et al., 2014) |

| 75.6±3.1 | 0.23±0.15 | 0.13±0.07 | Confined Compression | Bovine CEP Central | (Wu et al., 2015) |

| 70.2±1.8 | 0.83±0.26 | 0.09±0.03 | Confined Compression | Bovine CEP Peripheral | (Wu et al., 2015) |

| - | - | (1.19±1.64) ·105 | Permeameter | Human CEP | (Rodriguez et al., 2011) |

| 86.5±0.7 | 0.31±0.04 | 0.67±0.09 | Confined Compression | Bovine NP | (Périé et al., 2005) |

| 68.3±0.9 | 0.74±0.13 | 0.23±0.19 | Confined Compression | Bovine AF | (Périé et al., 2005) |

| 65±7 | 0.56±0.21 | 0.21±0.10 | Confined Compression | Human AF | (Iatridis et al., 1998) |

| 81.1±2 | 0.40±0.14 | 2.70±1.50 | Confined Compression | Bovine AC | (Ateshian et al., 1997) |

| ~73.1 | ~0.60 | ~1.48 | Indentation | Human AC | (Froimson et al., 1997) |

| - | 1.15±0.50 | 0.71±0.36 | Indentation | Human AC | (Athanasiou et al., 1994) |

Although hydraulic permeability and biochemical composition (porosity and s-GAG content) did not vary significantly across the four tested regions, there was notable evidence that the central CEP was more porous compared to the anterior CEP. This higher porosity in the central CEP was also evident when compared to pooled data from the other three peripheral endplate locations (Supp. Fig. 1). This aligns with previous findings which indicate the central region as being the most porous (Wu et al., 2016, 2015). A porous central CEP is suggested to facilitate nutrient diffusion into the nearby nucleus pulposus (Wu et al., 2016). Despite unclear regional heterogeneity in hydraulic permeability, which indicates relatively uniform fluid convection across the CEP, nutrient transport functions may still be regionally dependent due to differences in porosity and solute diffusivity alone (Urban et al., 1982; Wu et al., 2016). In this sense, a lower CEP stiffness in the center region, possibly associated with injury risk, may be a necessary tradeoff for better CEP nutrient exchange. While s-GAG content did not show regional dependency on a wet weight basis, there was evidence of regional dissimilarity between the central and anterior CEP on a dry weight basis (see Supp. Table 3). This corresponds with our previous finding showing higher dry weight s-GAG in the central CEP (Wu et al., 2016).

By correlating biochemical measurements with biphasic mechanical properties across the CEP specimens, it was found that porosity directly correlated with permeability and inversely correlated with swelling pressure and aggregate modulus. This supports previous hypotheses suggesting that water content is a key indicator of cartilaginous tissue biomechanical properties (Perie et al., 2006; Kuo et al., 2010; DeLucca et al., 2016). As higher water content corresponds to lower swelling pressure and matrix stiffness, it is reasonable that regional variation in these outcomes follow this relationship. Current findings of a softer and more porous central CEP compared to other CEP locations, agrees with this understanding. For s-GAG content, significant correlation was not found among any of the biphasic properties, illustrating its weak influence on CEP biomechanical and solute transport properties (Gu et al., 2004; Perie et al., 2006; Wu et al., 2016, 2017). One possible reason for this may be the relatively narrow range of variation in CEP s-GAG content in healthy discs. A study comparing biphasic properties between two healthy articular cartilage surfaces revealed that while s-GAG content correlated modestly with aggregate modulus in patellar cartilage, it did not correlate significantly in femoral cartilage, where the mean s-GAG content was greater by a margin of 5 μg/mg wet wt. (Froimson et al., 1997). The mean s-GAG content from the femoral cartilage was similar to that reported presently in the CEP (~35 μg/mg wet wt. for both tissues) (Froimson et al., 1997).

Multiphoton microscopy of the cartilage endplate (CEP) and the nearby transitional fiber layers of the disc revealed a distinct regional pattern of fiber anchoring. In the central region, the disc layer formed a clear boundary with the CEP, with fibers primarily oriented axially. In contrast, fibers in the anterior, lateral, and posterior regions anchored the endplate at off-axial angles. This off-axial orientation is likely expressed as an adaptation to bending loads experienced during flexion, extension, and side bending, potentially enhancing the compressive response of peripheral CEP areas in situ. In the anterior and lateral regions, CEP matrix fibers had no dominant orientation, but fibers were transversely oriented in the central and posterior regions. In central CEP, transverse fiber orientation may stem from tensile loads experienced in the transverse plane as it flexes during axial compression (Veres et al., 2010; Fields et al., 2010, 2014). Isotropic orientations in the anterior and lateral CEP could be explained by multidirectional loads generated through infrequent bending or shear in these regions. The posterior region, however, may take on transverse orientation due to compression experienced from normal spinal curvature (Been and Kalichman, 2014). Future studies should characterize fiber interdigitation within the transverse plane to better elucidate these phenomena.

Regional biphasic mechanical properties reported presently for the human CEP were robust, utilizing techniques comparable with previous cadaveric and animal model-based study designs (Setton et al., 1993; Périé et al., 2005; Cortes et al., 2014; Wu et al., 2015), however their spatial mapping had limitations. First, discrepancy in biphasic properties was noted between this study and previously reported data, possibly due to the different age groups examined (47±9 years vs. 60±12 years) (DeLucca et al., 2016). Influence of age, sex, disc level, and endplate site (inferior vs. superior side of the disc) on biomechanical and biochemical properties was also not reported, as they had no discernable effect on regional outcomes. This is potentially due to the small sample size used in this study, which may not be representative of the biologic heterogeneity among all healthy discs. Although it was expected that CEP tissue in peripheral locations would have lower hydraulic permeability, no regional variation was observed. One reason may be interdigitation of cartilage into the testing chamber porous plate, affecting measurement precision (Buschmann et al., 1998; Perie et al., 2006). Another likely factor is the lower magnitude of endplate permeability in relation to other disc tissues (Wu et al., 2015; DeLucca et al., 2016), rendering regional differences less apparent under this scale. Porosity differences were observed between central and anterior CEP, but high overall water content (up to 85%) and small tissue volumes (average of 0.013 cm3) may have masked broader spatial differences. Concerning the absence of regional variation in total s-GAG content and its lack of correlation with biphasic properties, it must be noted that the assay used in this study was unable to differentiate between specific s-GAG types. Species such as chondroitin sulfate (CS) and keratin sulfate (KS) for example, are known to vary in their regional distribution within the IVD (Stevens et al., 1979; Urban and Maroudas, 1980). They also differ in their contribution to the electrical fixed charge density of the tissue (CS carries two negative charges per disaccharide, twice as much as KS) (Jackson et al., 2009; Roberts et al., 1994; Stevens et al., 1979). These factors could obscure the effects of s-GAG on the CEP osmotic environment (Wu et al., 2017), and in turn the relationship of s-GAG with CEP biomechanical outcomes. Finally, the biphasic properties reported in this study were curve fit under confined compression conditions where the CEP collagen fibers experience minimal or no tension. Accordingly, no correlation was expected between either CEP collagen content or fiber orientation and the magnitude of these biphasic properties. Further research is needed to investigate regional tensile properties in the CEP and their relationships with collagen composition and fiber orientation to better understand the in situ CEP compressive response.

To summarize, this study demonstrates the heterogeneous nature of cartilage endplates in the human IVD, reporting variations in swelling pressure, aggregate modulus, water content, and fiber structure across its regions. Particularly, central CEP was less stiff and more porous than surrounding CEP tissue, a difference driven primarily by porosity, which correlated strongly with the biphasic properties. Stiffer peripherally located CEP likely complements the annulus fibrosus, providing resistance against non-uniform compression through bending of the IVD. Conversely, softer, and more porous central CEP may elucidate known mechanisms of CEP injury, such as nucleus pulposus protrusion into underlying vertebrae, while potentially facilitating nutrient supply to the IVD nucleus as a tradeoff.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH/NIGMS COBRE: South Carolina Translational Research Improving Musculoskeletal Health (SC TRIMH; P20GM121342), NIH: R01DE021134, and the Cervical Spine Research Society Seed Starter Grant.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest statement

None of the authors of this paper have a conflict of interest that might be construed as affecting the conduct or reporting of the work presented.

References

- Adams M, Dolan P, Hutton W, Porter R, 1990. Diurnal changes in spinal mechanics and their clinical significance. J Bone Joint Surg Br 72-B, 266–270. 10.1302/0301-620X.72B2.2138156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams MA, Roughley PJ, 2006. What is intervertebral disc degeneration, and what causes it? Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 31, 2151–2161. 10.1097/01.brs.0000231761.73859.2c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen KD, Athanasiou KA, 2005. A surface-regional and freeze-thaw characterization of the porcine temporomandibular joint disc. Ann Biomed Eng 33, 951–962. 10.1007/s10439-005-3872-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso F, Hart DJ, 2014. Intervertebral Disk, in: Aminoff MJ, Daroff RB. (Eds.), Encyclopedia of the Neurological Sciences (Second Edition). Academic Press, Oxford, pp. 724–729. 10.1016/B978-0-12-385157-4.01154-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ateshian GA, Warden WH, Kim JJ, Grelsamer RP, Mow VC, 1997. Finite deformation biphasic material properties of bovine articular cartilage from confined compression experiments. J Biomech 30, 1157–1164. 10.1016/s0021-9290(97)85606-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Athanasiou KA, Agarwal A, Dzida FJ, 1994. Comparative study of the intrinsic mechanical properties of the human acetabular and femoral head cartilage. J Orthop Res 12, 340–349. 10.1002/jor.1100120306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Been E, Kalichman L, 2014. Lumbar lordosis. Spine J 14, 87–97. 10.1016/j.spinee.2013.07.464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blattner T, Keyrouz W, Chalfoun J, Stivalet B, Brady M, Zhou S, 2014. A Hybrid CPU-GPU System for Stitching Large Scale Optical Microscopy Images. Presented at the 2014 43rd International Conference on Parallel Processing, pp. 1–9. 10.1109/ICPP.2014.9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buckwalter JA, 1995. Aging and degeneration of the human intervertebral disc. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 20, 1307–1314. 10.1097/00007632-199506000-00022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buschmann MD, Soulhat J, Shirazi-Adl A, Jurvelin JS, Hunziker EB, 1998. Confined compression of articular cartilage: linearity in ramp and sinusoidal tests and the importance of interdigitation and incomplete confinement. J Biomech 31, 171–178. 10.1016/s0021-9290(97)00124-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne RM, Aiyangar AK, Zhang X, 2019. A Dynamic Radiographic Imaging Study of Lumbar Intervertebral Disc Morphometry and Deformation In Vivo. Sci Rep 9, 15490. 10.1038/s41598-019-51871-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalfoun J, Majurski M, Blattner T, Bhadriraju K, Keyrouz W, Bajcsy P, Brady M, 2017. MIST: Accurate and Scalable Microscopy Image Stitching Tool with Stage Modeling and Error Minimization. Sci Rep 7, 4988. 10.1038/s41598-017-04567-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coombs MC, Petersen JM, Wright GJ, Lu SH, Damon BJ, Yao H, 2017. Structure-Function Relationships of Temporomandibular Retrodiscal Tissue. J Dent Res 96, 647–653. 10.1177/0022034517696458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortes DH, Jacobs NT, DeLucca JF, Elliott DM, 2014. Elastic, permeability and swelling properties of human intervertebral disc tissues: A benchmark for tissue engineering. J Biomech 47, 2088–2094. 10.1016/jjbiomech.2013.12.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLucca JF, Cortes DH, Jacobs NT, Vresilovic EJ, Duncan RL, Elliott DM, 2016. Human cartilage endplate permeability varies with degeneration and intervertebral disc site. J Biomech 49, 550–557. 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2016.01.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhillon N, Bass EC, Lotz JC, 2001. Effect of frozen storage on the creep behavior of human intervertebral discs. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 26, 883–888. 10.1097/00007632-200104150-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowdell J, Erwin M, Choma T, Vaccaro A, Iatridis J, Cho SK, 2017. Intervertebral Disk Degeneration and Repair. Neurosurgery 80, S46–S54. 10.1093/neuros/nyw078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudli S, Fields AJ, Samartzis D, Karppinen J, Lotz JC, 2016. Pathobiology of Modic changes. Eur Spine J 25, 3723–3734. 10.1007/s00586-016-4459-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan H, Xu P, Chen X, Li Y, Zhang Z, Hsu J, Le M, Ye E, Gao B, Demos H, Yao H, Ye T, 2023. Mask R-CNN provides efficient and accurate measurement of chondrocyte viability in the label-free assessment of articular cartilage. Osteoarthr Cartil Open 5, 100415. 10.1016/j.ocarto.2023.100415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields AJ, Ballatori A, Liebenberg EC, Lotz JC, 2018. Contribution of the endplates to disc degeneration. Curr Mol Biol Rep 4, 151–160. 10.1007/s40610-018-0105-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields AJ, Lee GL, Keaveny TM, 2010. Mechanisms of initial endplate failure in the human vertebral body. J Biomech 43, 3126–3131. 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2010.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields AJ, Rodriguez D, Gary KN, Liebenberg EC, Lotz JC, 2014. Influence of biochemical composition on endplate cartilage tensile properties in the human lumbar spine.J. Orthop. Res 32, 245–252. 10.1002/jor.22516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields AJ, Sahli F, Rodriguez AG, Lotz JC, 2012. Seeing double: a comparison of microstructure, biomechanical function, and adjacent disc health between double- and single-layer vertebral endplates. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 37, E1310–1317. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318267bcfc [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froimson MI, Ratcliffe A, Gardner TR, Mow VC, 1997. Differences in patellofemoral joint cartilage material properties and their significance to the etiology of cartilage surface fibrillation. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 5, 377–386. 10.1016/s1063-4584(97)80042-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant JP, Oxland TR, Dvorak MF, 2001. Mapping the structural properties of the lumbosacral vertebral endplates. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 26, 889–896. 10.1097/00007632-200104150-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu W, Lewis B, Lai WM, Ratcliffe A, Mow VC, 1996. A Technique for Measuring Volume and True Density of the Solid Matrix of Cartilaginous Tissues, in: ASME 1996 International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition. Advances in Bioengineering. pp. 89–90. 10.1115/IMECE1996-1128 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gu WY, Justiz M-A, Yao H, 2002. Electrical conductivity of lumbar anulus fibrosis: effects of porosity and fixed charge density. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 27, 2390–2395. 10.1097/00007632-200211010-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu WY, Yao H, Vega AL, Flagler D, 2004. Diffusivity of ions in agarose gels and intervertebral disc: effect of porosity. Ann Biomed Eng 32, 1710–1717. 10.1007/s10439-004-7823-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch C, Galante J, 1967. Laboratory conditions for tensile tests in annulus fibrosus from human intervertebral discs. Acta Orthop Scand 38, 148–162. 10.3109/17453676708989629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y-C, Urban JPG, Luk KDK, 2014. Intervertebral disc regeneration: do nutrients lead the way? Nat Rev Rheumatol 10, 561–566. 10.1038/nrrheum.2014.91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iatridis JC, MaClean JJ, Ryan DA, 2005. Mechanical damage to the intervertebral disc annulus fibrosus subjected to tensile loading. J Biomech 38, 557–565. 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.03.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iatridis JC, Setton LA, Foster RJ, Rawlins BA, Weidenbaum M, Mow VC, 1998. Degeneration affects the anisotropic and nonlinear behaviors of human anulus fibrosus in compression. J Biomech 31, 535–544. 10.1016/s0021-9290(98)00046-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson AR, Huang C-Y, Gu WY, 2011. Effect of endplate calcification and mechanical deformation on the distribution of glucose in intervertebral disc: a 3D finite element study. Comput Methods Biomech Biomed Engin 14, 195–204. 10.1080/10255842.2010.535815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson AR, Yuan T-Y, Huang C-Y, Gu WY, 2009. A Conductivity Approach to Measuring Fixed Charge Density in Intervertebral Disc Tissue. Ann Biomed Eng 37, 2566–2573. 10.1007/s10439-009-9792-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo J, Zhang L, Bacro T, Yao H, 2010. The region-dependent biphasic viscoelastic properties of human temporomandibular joint discs under confined compression. J Biomech 43, 1316–1321. 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2010.01.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotz JC, Fields AJ, Liebenberg EC, 2013. The role of the vertebral end plate in low back pain. Global Spine J 3, 153–164. 10.1055/s-0033-1347298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotz JC, Ulrich JA, 2006. Innervation, inflammation, and hypermobility may characterize pathologic disc degeneration: review of animal model data. J Bone Joint Surg Am 88 Suppl 2, 76–82. 10.2106/JBJS.E.01448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mow VC, Kuei SC, Lai WM, Armstrong CG, 1980. Biphasic creep and stress relaxation of articular cartilage in compression: Theory and experiments. J Biomech Eng 102, 73–84. 10.1115/1.3138202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Périé D, Korda D, Iatridis JC, 2005. Confined compression experiments on bovine nucleus pulposus and annulus fibrosus: sensitivity of the experiment in the determination of compressive modulus and hydraulic permeability. J Biomech 38, 2164–2171. 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perie DS, Maclean JJ, Owen JP, Iatridis JC, 2006. Correlating material properties with tissue composition in enzymatically digested bovine annulus fibrosus and nucleus pulposus tissue. Ann Biomed Eng 34, 769–777. 10.1007/s10439-006-9091-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro J, Bates D, R Core Team, 2023. nlme: Linear and Nonlinear Mixed Effects Models. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team, 2023. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. [Google Scholar]

- Rezakhaniha R, Agianniotis A, Schrauwen JTC, Griffa A, Sage D, Bouten CVC, van de Vosse FN, Unser M, Stergiopulos N, 2012. Experimental investigation of collagen waviness and orientation in the arterial adventitia using confocal laser scanning microscopy. Biomech Model Mechanobiol 11, 461–473. 10.1007/s10237-011-0325-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risbud MV, Shapiro IM, 2014. Role of cytokines in intervertebral disc degeneration: pain and disc content. Nat Rev Rheumatol 10, 44–56. 10.1038/nrrheum.2013.160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts S, Caterson B, Evans H, Eisenstein SM, 1994. Proteoglycan components of the intervertebral disc and cartilage endplate: an immunolocalization study of animal and human tissues. Histochem J 26, 402–411. 10.1007/BF00160052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts S, Menage J, Eisenstein SM, 1993. The cartilage end-plate and intervertebral disc in scoliosis: calcification and other sequelae. J Orthop Res 11, 747–757. 10.1002/jor.1100110517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts S, Menage J, Urban JP, 1989. Biochemical and structural properties of the cartilage end-plate and its relation to the intervertebral disc. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 14, 166–174. 10.1097/00007632-198902000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts S, Urban JP, Evans H, Eisenstein SM, 1996. Transport properties of the human cartilage endplate in relation to its composition and calcification. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 21, 415–420. 10.1097/00007632-199602150-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez AG, Slichter CK, Acosta FL, Rodriguez-Soto AE, Burghardt AJ, Majumdar S, Lotz JC, 2011. Human Disc Nucleus Properties and Vertebral Endplate Permeability. Spine 36, 512. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181f72b94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan G, Pandit A, Apatsidis D, 2008. Stress distribution in the intervertebral disc correlates with strength distribution in subdiscal trabecular bone in the porcine lumbar spine. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 23, 859–869. 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2008.03.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, Kaynig V, Longair M, Pietzsch T, Preibisch S, Rueden C, Saalfeld S, Schmid B, Tinevez J-Y, White DJ, Hartenstein V, Eliceiri K, Tomancak P, Cardona A, 2012. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods 9, 676–682. 10.1038/nmeth.2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setton LA, Zhu W, Weidenbaum M, Ratcliffe A, Mow VC, 1993. Compressive properties of the cartilaginous end-plate of the baboon lumbar spine. J Orthop Res 11, 228–239. 10.1002/jor.1100110210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smeathers JE, Joanes DN, 1988. Dynamic compressive properties of human lumbar intervertebral joints: a comparison between fresh and thawed specimens. J Biomech 21, 425–433. 10.1016/0021-9290(88)90148-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soukane DM, Shirazi-Adl A, Urban JPG, 2007. Computation of coupled diffusion of oxygen, glucose and lactic acid in an intervertebral disc. J Biomech 40, 2645–2654. 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2007.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens RL, Ewins RJ, Revell PA, Muir H, 1979. Proteoglycans of the intervertebral disc. Homology of structure with laryngeal proteoglycans. Biochem J 179, 561–572. 10.1042/bj1790561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JP, Pearce RH, Schechter MT, Adams ME, Tsang IK, Bishop PB, 1990. Preliminary evaluation of a scheme for grading the gross morphology of the human intervertebral disc. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 15, 411–415. 10.1097/00007632-199005000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsantrizos A, Ito K, Aebi M, Steffen T, 2005. Internal strains in healthy and degenerated lumbar intervertebral discs. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 30, 2129–2137. 10.1097/01.brs.0000181052.56604.30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urban J, Maroudas A, 1980. The Chemistry of the Intervertebral Disc in Relation to its Physiological Function and Requirements. Clin Rheum Dis 6, 51–76. 10.1016/S0307-742X(21)00280-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Urban JP, Holm S, Maroudas A, Nachemson A, 1982. Nutrition of the intervertebral disc: effect of fluid flow on solute transport. Clin Orthop Relat Res 296–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urban JP, Roberts S, 1995. Development and degeneration of the intervertebral discs. Mol Med Today 1, 329–335. 10.1016/s1357-4310(95)80032-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veres SP, Robertson PA, Broom ND, 2010. ISSLS prize winner: how loading rate influences disc failure mechanics: a microstructural assessment of internal disruption. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 35, 1897–1908. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181d9b69e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Cisewski S, Sachs BL, Yao H, 2013. Effect of cartilage endplate on cell based disc regeneration: a finite element analysis. Mol Cell Biomech 10, 159–182. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Cisewski SE, Sachs BL, Pellegrini VD, Kern MJ, Slate EH, Yao H, 2015. The region-dependent biomechanical and biochemical properties of bovine cartilaginous endplate. J Biomech 48, 3185–3191. 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2015.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Cisewski SE, Sun Y, Damon BJ, Sachs BL, Pellegrini VD, Slate EH, Yao H, 2017. Quantifying Baseline Fixed Charge Density in Healthy Human Cartilage Endplate: A Two-point Electrical Conductivity Method. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 42, E1002–E1009. 10.1097/BRS.0000000000002061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Cisewski SE, Wegner N, Zhao S, Pellegrini VDJ, Slate EH, Yao H, 2016. Region and strain-dependent diffusivities of glucose and lactate in healthy human cartilage endplate. J Biomech 49, 2756–2762. 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2016.06.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao H, Justiz M-A, Flagler D, Gu WY, 2002. Effects of swelling pressure and hydraulic permeability on dynamic compressive behavior of lumbar annulus fibrosus. Ann Biomed Eng 30, 1234–1241. 10.1114/1.1523920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao F-D, Pollintine P, Hole BD, Adams MA, Dolan P, 2009. Vertebral fractures usually affect the cranial endplate because it is thinner and supported by less-dense trabecular bone. Bone 44, 372–379. 10.1016/j.bone.2008.10.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M, Lim S, O’Connell GD, 2021. A Robust Multiscale and Multiphasic Structure-Based Modeling Framework for the Intervertebral Disc. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 9, 685799. 10.3389/fbioe.2021.685799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.