Malocclusion is the abnormal positioning of the teeth or jaws. It is a variation of growth and development and can affect a person's bite (occlusion), ability to clean teeth properly, gingival health, jaw growth, speech development, and appearance.

The shape and size of the face, jaws, and teeth are mainly inherited, but environmental factors can also have an impact. Factors as diverse as skeletal muscle pathology1 and sucking a digit (thumb or finger) can substantially influence the growth of the face and dentition.

Treatment of disorders such as crowded or protruding teeth may improve both aesthetics and oral function. In addition, prominent teeth can be damaged easily during childhood. The dental specialty most concerned with problems of facial growth, development of occlusion, and the prevention and correction of associated anomalies is orthodontics. The improvement of occlusion and aesthetics using restorative dental techniques is discussed in the next article.

Orthodontic care

The demand for orthodontic treatment is increasing to such an extent that an objective index of orthodontic treatment need (IOTN) has been established to ensure that resources are directed to patients with the greatest clinical need and who are likely to benefit most.2,3

Prevention or treatment of malocclusion may help• Aesthetic appearance• Occlusion• Oral health• Reduce dental trauma

Apart from a thorough history and examination, photographs of the face and teeth and models of the teeth are used to provide a record and facilitate treatment planning. Several types of radiograph may also be needed. Most commonly used are panoramic radiographs, which show all the upper and lower teeth in biting position as well as any teeth still developing within the jaws, and a lateral cephalometric radiograph, which shows the relation of the teeth and jaws to the face and base of the skull.

Treatment

Tooth extraction

Carefully controlled removal of selected primary teeth may be prescribed to facilitate the eruption of the permanent teeth into their correct position. Orthodontic treatment may also require healthy permanent teeth to be extracted when there is dento-alveolar disproportion—that is, a discrepancy in the size of the jaw in relation to the teeth present. Some malocclusions cannot be treated successfully without removing permanent teeth, though tooth removal is contraindicated in other situations. Typically, premolars are selected for extraction since this maintains aesthetics, but other teeth may be extracted if they are heavily filled, decayed, or have poor long term prognosis. Only very rarely are anterior teeth extracted for orthodontic reasons.

• The index of orthodontic treatment need is frequently used to determine clinical need and potential benefit• Space in the dental arch is gained by tooth movement or extraction• Teeth are generally moved by wires and springs on removable or fixed appliances• Treatment typically takes 18-30 months• Early treatment is often simpler and more effective than later treatment• Timing of referral in children is important• Screening for malocclusion by general dental practitioners is recommended at 9-10 years of age

Tooth movement

Treatment involves moving the teeth through the supporting alveolar bone to the desired position. This must be carried out slowly and carefully to avoid pain or damage to the teeth. It is done by means of fixed or removable appliances (braces) that gently move the teeth and supporting alveolar bone until they are in the desired position. The braces consist of brackets, made of metal, ceramics, or plastic, and an archwire that connects them. The teeth are moved by adjusting the pressures on them via the archwire. Springs or elastic bands may be used to help. The appliances are tightened periodically, and some discomfort is then felt for a few hours. It should be noted that placement and removal of orthodontic bands can cause a transient bacteraemia, and in cases with a risk of infective endocarditis appropriate antibiotic cover should be administered.4,5

The length of time required to move teeth to the desired location varies considerably. The average for children is 18-30 months, but it is generally longer for adults. The time required depends on the malocclusion complexity, amount of space available, distance the teeth must move, cooperation of the patient, bone density, and age of the patient.

When the desired occlusion has been achieved and the braces removed, a retainer is used, typically for 6-12 months, to prevent the teeth reverting towards their original positions. In some cases, retention may be needed long term.

Other types of brace include functional appliances which are orthopaedic devices designed to modify jaw growth, particularly in patients with a recessive lower jaw. In some situations additional components, such as extraoral appliances, may be worn to complement fixed or removable appliances, and these are generally worn only during the evening and night.

Orthodontics in children and adolescents

Most orthodontic treatment is carried out during childhood since the teeth can then most readily be moved. Some problems are treated most effectively when the child is actively growing, and, for this reason, the timing of referral is critical. This particularly applies to children with very prominent upper teeth and a small lower jaw. Failure to treat at the appropriate age may mean that orthodontic correction of the problem is not feasible and that the patient will require orthognathic surgery at a later stage. All children should be screened at about 9-10 years of age by their dental practitioner, and appropriate referral for a specialist opinion instigated where necessary.

Orthodontics in adults

Orthodontics is increasingly used in adults. This may involve orthodontics alone or orthodontics together with intervention from another dental discipline. Thus, orthodontic care may be required when teeth need to be moved to allow ideal restorations (such as crowns or bridges) to be placed.

Orthognathic surgery

When there is a severe skeletal discrepancy or there is no growth allowing orthopaedic correction, orthodontics alone will not solve the problem. Patients who present with severe dentofacial problems (such as an extremely recessive or protruding mandible or facial asymmetries) may require a combination of fixed braces to place the teeth in an ideal position followed by maxillofacial surgery to reposition the jaws in the correct relationship (orthognathic treatment). This form of treatment is undertaken when growth is complete and can produce marked improvements in facial and dental appearance and in oral function. These improvements often lead to improvements in patients' self confidence, their ability to interact socially, and how they are perceived by others.6

• Severe malocclusions may be disfiguring and not correctable by orthodontics alone• A combination of orthodontics and orthognathic surgery may be indicated• Some malocclusions may be amenable to distraction osteogenesis

Distraction osteogenesis, the forcible lengthening of bone, is being developed for patients with severe dentofacial problems, including adults and some children with syndromes manifesting severe deformities (such as the midfacial deformity typical of Crouzon syndrome).

Cleft lip and palate and facial syndromes

Cleft lip and palate

Cleft lip and palate is the most common congenital deformity in the craniofacial region, with an incidence of about 1 in 700 live births. The presentation may range from a bifid uvula, often associated with a submucous cleft, to a complete bilateral cleft of the lip and palate. Submucous clefts are often not recognised early as there is apparently an intact soft palate, but the muscle alignment is abnormal and may give rise to poor speech development.

An orthodontist should attend a baby with cleft lip or palate as soon as possible after birth in order to decide whether to construct a feeding plate and to advise the parents on future management. The child will continue to be seen regularly by the orthodontist and will require intervention at several stages during development as well as careful dental care.

The orthodontist will monitor facial growth and development of the dentition. Active treatment is required before bone grafting of the alveolar palatal defect at about 10 years of age. This timing is dictated by the stage of dental development, when the canine tooth will erupt through the newly placed bone graft. When the permanent teeth have erupted then comprehensive orthodontic treatment is often indicated. There may be extra or missing teeth or teeth with poor prognosis in the site of the cleft. The orthodontist must take all these factors into account when planning definitive treatment, which may involve dental extractions and the use of fixed appliances.

• Management of cleft lip and palate involves a team approach with orthodontists and surgeons in key roles• Crucial treatment times for a patient with cleft palate are before bone grafting (around 10 years) and when the permanent teeth have erupted

Patients with clefts of the lip and palate often present with facial growth problems, with the maxilla being recessive relative to the mandible, and these patients may well require some form of orthognathic surgery when growth has ceased. As with all stages of treatment, if orthognathic surgery is required this should be planned carefully by the orthodontist, maxillofacial surgeon, otorhinolaryngologist, plastic surgeon, restorative dentist, and speech therapist for optimal results.

Facial syndromes

Some syndromes affecting the craniofacial region are relatively minor (such as cleidocranial dysplasia), but others are much more severe (such as first arch syndrome, Crouzon syndrome, and Apert syndrome). Many require orthodontic care, conducted in major regional craniofacial centres. Orthodontists also play a role in diagnosing systemic conditions that affect facial growth or development of the dentition, such as acromegaly or Marfan's syndrome. These may require orthodontic or surgical intervention to correct the associated problems.

Figure.

Patient with crowded teeth and malocclusion (top) and after orthodontic treatment (bottom)

Figure.

Dentition of a 21 year old man who would benefit from orthodontic treatment to relocate spaces in lower jaw before bridges are placed to correct aesthetic appearance

Figure.

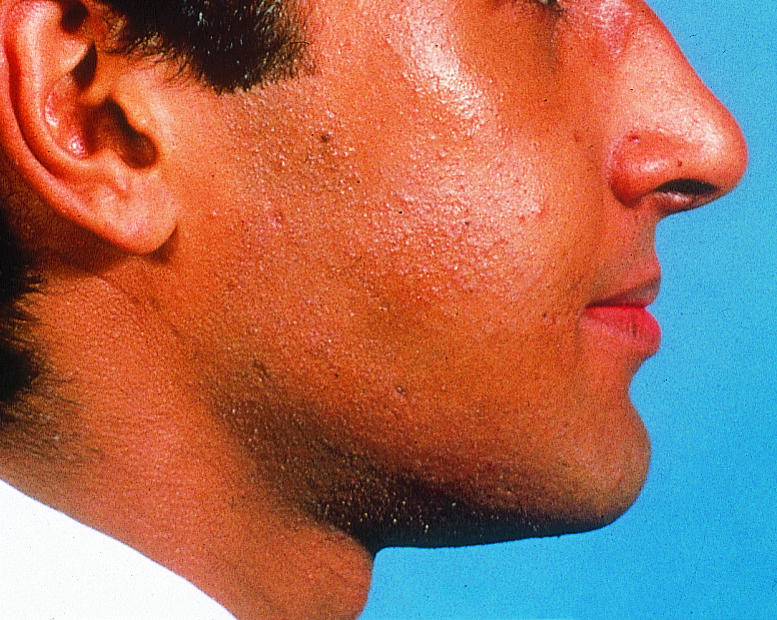

Profile view of patient with protruding mandible (top) and after orthognathic treatment (bottom)

Figure.

Palatal view of patient with cleft lip and palate

Acknowledgments

Crispian Scully is grateful for the advice of Rosemary Toy, general practitioner, Rickmansworth, Hertfordshire.

Footnotes

Susan Cunningham is lecturer, Elisabeth Horrocks is consultant, Nigel Hunt is professor of orthodontics, Steven Jones is consultant, Howard Moseley is consultant, Joseph Noar is consultant, and Crispian Scully is dean at the Eastman Dental Institute for Oral Health Care Sciences, University College London, University of London (www.eastman.ucl.ac.uk).

The ABC of oral health is edited by Crispian Scully and will be published as a book in autumn 2000.

References

- 1.Hunt NP. Muscle function and the control of facial form. In: Harris M, Edgar M, Meghji S, editors. Clinical oral science. Oxford: Wright; 1998. pp. 120–133. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brook PH, Shaw WC. The development of an index of orthodontic treatment priority. Eur J Orthod. 1989;11:309–320. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.ejo.a035999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Otuyemi OD, Jones SP. Methods of assessing and grading malocclusion: A review. Aust Orthod J. 1995;14:21–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Erverdi N, Kadir T, Ozkan H, Acar A. Investigation of bacteremia after orthodontic banding. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1999;116:687–690. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(99)70205-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khurana M, Martin MV. Orthodontics and infective endocarditis. Br J Orthod. 1999;26:295–298. doi: 10.1093/ortho/26.4.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cunningham SJ, Hunt NP, Feinmann C. Psychological aspects of orthognathic surgery—A review of the literature. Int J Adult Orthod Orthognath Surg. 1995;10:159–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]