Abstract

Application of chemical acaricides in the control of ticks has led to the problem of tick-acaricide control failure. To obtain an understanding of the possible risk factors involved in this tick-acaricide control failure, this study investigated tick control practices on communal farms in the north-eastern part of the Eastern Cape Province (ECP) of South Africa. A semi-structured questionnaire designed to document specific farm attributes and acaricide usage practices was administered at 94 communal farms from the Oliver Tambo District municipality of the ECP. Data collected indicated that the main acaricide chemicals used at plunge dips of inland and coastal areas were synthetic pyrethroid formulations. Most (75%) farmers claimed not to have noticed a significant reduction in numbers of actively feeding and growing ticks on cattle after several acaricide treatments. Based on the farmers’ perceptions, leading factors that could have led to tick-acaricide control failure included: weak strength of the dip solution (76%); poor structural state of dip tanks (42%); and irregular tick control (21%). The rearing of crossbreeds of local and exotic cattle breeds, perceived weak strength of the dip solution and high frequency of acaricide treatment, were statistically associated with proportions of farms reporting tick-acaricide control failure. Furthermore, approximately 50% of farms reported at least four tick control malpractices, which could have resulted in the emergence and spread of tick-acaricide control failure. Other sub-optimal tick control practices encountered included incorrect acaricide rotation, and failure to treat all cattle in a herd. This data will inform and guide the development of management strategies for tick-acaricide control failure and resistance in communal farming areas.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10493-024-00910-x.

Keywords: Cattle production, Tick control, Acaricide, Application practices, Control failure

Introduction

The communal farming sector provides the highest percentage (78%) of cattle within the Eastern Cape Province (ECP) of South Africa (Goni et al. 2018), yet the proportion of animals sold or consumed per year is low compared to the commercial farming sector (Musemwa et al. 2010). Ixodid ticks and tick-borne diseases (TBDs) have been highlighted as one of the major challenges facing communal cattle production (Moyo and Masika 2009; Sungirai et al. 2016; Goni et al. 2018,). Tick control on cattle in communal areas of the ECP is a free service provided for by the Provincial government through the District Veterinary Services (Moyo and Masika 2009). The Provincial government is responsible for the provision of acaricides, technical personnel and infrastructure. The control of ticks on cattle within the ECP is mainly through the use of plunge dips (Ntondini et al. 2008). However, tick-acaricide control failure has greatly moderated the efforts that have been made to control ticks and TBDs in South Africa (Moyo and Masika 2009). To lessen the effects of tick-acaricide control failure, farmers have often supplemented the government provided dipping services with their own initiatives including use of commercially accessible chemical acaricides applied as sprays and pour-ons, use of household disinfectants, engine oils, plant extracts, predation by chickens and manual removal (Moyo and Masika 2009).

Acaricide resistance which is a heritable reduction in susceptibility of a tick population to an acaricide expressed by repeated failure of the acaricide to achieve the expected level of control when used according to the label recommendation (FAO 2004; Rodriguez et al. 2018), is perhaps one of the several causes of acaricide control failure. The pace at which tick resistance develops is strongly influenced by poor acaricide application practices (Abbas et al. 2014). Acaricide resistance in field studies have been reported worldwide (Rodriguez et al. 2018). Several factors have been associated with increased probability of acaricide resistance and consequently acaricide control failure. These include frequency of application, type of application, farm localization, grazing management, cattle breed, incorrect dilution of acaricides, failure to treat all cattle in a herd and incorrect acaricide rotation (Spickett and Fivaz 1992; Moyo and Masika 2009; Vudriko et al. 2018; Rodriguez et al. 2018).

In the ECP of South Africa, studies have been conducted to assess the effectiveness of tick control practices in the commercial cattle production sector (Spickett and Fivaz 1992). However, in a study on tick control methods used by resource-limited farmers in communal cattle production areas, Moyo and Masika (2009) did not adequately investigate control practices associated with tick-acaricide control failure. Moreover, their study was conducted almost 10 years ago, and over time farming practices change, thus the need to assess the current tick control practices. Furthermore, in view of the reported wide spread prevalence of tick-acaricide control failure especially in communal areas of the Eastern Cape (Mekonnen et al. 2002; Moyo and Masika 2009), assessment of the current tick control practices is a prelude for the management of acaricide control failure in tick control programmes. Therefore, this study attempted to document farm attributes and control practices associated with the development of tick-acaricide control failure in communal areas of the ECP of South Africa.

Materials and methods

Study area and design

The study was conducted from August 2018 to May 2019 at the Oliver Tambo District municipality (ORTDM), situated in the north-eastern part of the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa. There are five local municipalities (LM) within the ORTDM namely; King Sabata Dalindyebo (KSD), Mhlontlo, Nyandeni, Port St Johns and Ingquza (Fig. 1). All of these LMs, with the exception of KSD, are rural in nature with a subsistence economy. The ORTDM has the largest communal livestock farming in South Africa, incorporating 631 674 cattle, 732 478 goats and 1 225 244 sheep (IDP 2017). Communal areas comprise of villages, with land apportioned for residential, cropping and grazing purposes. Grazing areas are collectively shared by all villagers for rearing of different livestock including cattle, sheep, goats, horses and donkeys. Other agricultural activities practiced within the district include maize, vegetable, fruit and tea production, forestry, game rearing, apiculture and aquaculture. Most parts of the ORTDM receive an annual rainfall of above 900 mm and its environment has a wide range of habitats including inland and coastal grassland, Afromontane and coastal forest, valley thicket, thorny bushveld, coastal and marine habitats (IDP 2017).

Fig. 1.

Map of OR Tambo district municipality showing locations of communal farms included in the study

There are approximately 355 dip tank stations (farms) within the ORTDM, of which 145 and 210 are located within the coastal and inland areas, respectively. Data on the number of dipping tanks and corresponding cattle population serviced at the various dip tanks were obtained from the Office of District Director in charge of Veterinary Services. Through a purposive sampling process based on the cattle population size (≥ 1000) serviced at the dipping tanks, a total of 148 inland and 72 coastal dipping tanks were selected, from which a random sample comprising 50% of the eligible dipping tanks was obtained. Hence for data collection, a total of 74 and 36 dipping tanks from the inland and coastal areas of the ORTDM, respectively, were considered.

The survey instrument

A semi-structured questionnaire was used to document data on the attributes and control practices that could have resulted in the development of tick-acaricide control failure at the communal farms. The survey tool was designed to capture data on tick control methods and practices; acaricides used; animal husbandry and acaricide application practices; farmers’ perceptions on the causes of tick-acaricide control failure; and tick-acaricide control failure mitigation strategies. Tick-acaricide control failure was assessed by asking farmers if they had noticed a significant reduction in numbers of active ticks (feeding and growing) on cattle after several acaricide treatments (dipping). The survey tool was administered in the local isiXhosa language, since a majority of the communal farmers had little or no formal educational background and were not familiar with some terminologies used in the questionnaire. Prior to the administration of questionnaires, an informed oral consent was obtained from the Animal Health Technicians (AHTs), Community Animal Health Workers (CAHWs) and cattle farmers. Farmers were also assured of the confidentiality of their responses. Questionnaires were then administered to farmers on days of cattle treatment against ticks at the different dip tanks. The respondents were either delegated members of the dip tank committee (also cattle owners) or a group of cattle farmers who had finished the task of dipping the cattle. With the latter, a common consensus was reached before responses were recorded.

Data analysis

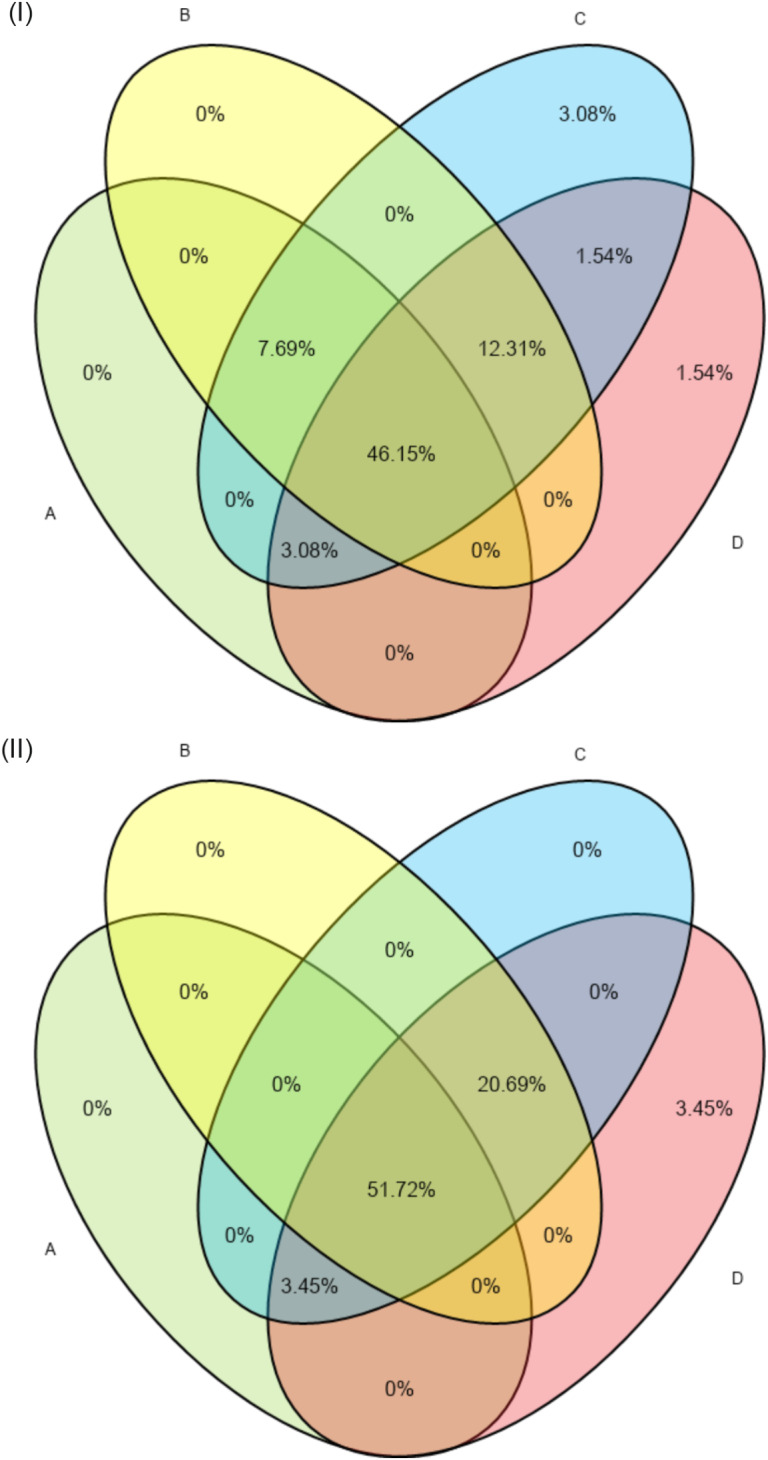

Data obtained from the questionnaires was summarised, coded and entered into Microsoft® Excel® 2016. Counts, frequencies and percentages were generated and analysed in GraphPad Prism 8 for Windows version 8.01. The Fischer’s Exact probability test was used to determine whether risky tick control practices were significantly (two tailed P value ≤ 0.05) associated with proportion of farms reporting tick-acaricide control failure. Furthermore, Venn diagrams were used to illustrate the proportion of farms with combinations of multiple risk factors associated with tick-acaricide control failure.

Results

General characteristics of the communal cattle farms

86% (94/110) of the sampled communal farms participated in the survey, of which a majority (43%) were from the KSD local municipality (Table 1). Respondents were either a group of ordinary cattle owners (49%) or members of the dipping tank committee (51%), who had no other formal jobs (96%) apart from livestock rearing. Cattle breeds mostly kept were crossbreeds of the local Nguni and exotic breeds (68%). Cattle were kept alongside other livestock including sheep (88%), goats (73%), and horses (54%). All these ruminants were either bred on grassland vegetation (63%), or both grassland and forest vegetation (45%). Cattle interaction with wildlife in the course of feeding was minimal (23%).

Table 1.

General characteristics of the studied communal cattle farming areas within OR Tambo district of South Africa

| Query | Level | Percentage reponse per area | Percent of total (n = 94) | |

| Inland (n = 65)# | Coastal (n = 29) | |||

| Local municipality | KSD | 40 (26) | 45 (13) | 41 (39) |

| Mhlonto | 35 (23) | 0 (0) | 25 (23) | |

| Port St Johns | 0 (0) | 10 (3) | 3 (3) | |

| Ingquza hill | 10 (6) | 17 (5) | 12 (11) | |

| Nyandeni | 15 (10) | 28 (8) | 19 (18) | |

| Position at the communal farm | Cattle farmer | 41 (27) | 66 (19) | 49 (46) |

| Dipping tank committee member | 59 (38) | 35 (10) | 51 (48) | |

| Breed of cattle reared | *Crossbreeds only | 63 (41) | 79 (23) | 68 (64) |

| Both Local and crossbreeds | 37 (24) | 21 (6) | 32 (30) | |

| aKeeping of other livestock | Sheep | 89 (58) | 86 (25) | 88 (83) |

| Goat | 66 (43) | 90 (26) | 73 (69) | |

| Horses | 45 (29) | 76 (22) | 54 (51) | |

| Pigs | 20 (13) | 24 (7) | 21 (20) | |

| bVegetation cattle feed on | Grassland only | 72 (47) | 55 (16) | 67 (63) |

| Grassland and forest | 37 (24) | 62 (18) | 44 (42) | |

| Interaction between cattle and wildlife | Yes | 14 (9) | 45 (13) | 23 (22) |

| No | 86 (56) | 55 (16) | 77 (72) | |

Abbreviation KSD, King Sabata Dalindyebo

* Crossbreeds of the local Nguni and exotic cattle

#Numbers in brackets indicate number of responses

aSome farmers had a combination of other livestock, and combinations of livestock were not accounted for

bSome farmers grazed their cattle in both grassland-only and grassland-and-forest areas

Cattle ticks, their effects and control

A majority (95%) of farmers indicated that their cattle were infested with ticks. Based on the blue colour of engorged female ticks, as well as coloured patterns on scutum and coloured rings on legs of bont-legged ticks, Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) spp. (95%) and Amblyomma spp. (55%) were mostly reported (Table 2). Bont-legged ticks were reportedly present on majority cattle (83%) kept at the coastal communal areas. Furthermore, farmers indicated that greater number of active ticks were found on cattle during the summer (86%). With regards to the effects of ticks, a majority (95%) of farmers knew that tick infestations led to weight loss, TBDs, and wounds on body, ears, udder, teat and tail of the animal. In addition, some farmers mentioned that tick infestations also lead to abscesses (28%) and loss of appetite (5%) in cattle. Tick control at the communal farms was conducted mainly by immersing cattle into an acaricide solution in a dip tank. Other tick control measures encountered included: the use of home-made remedies (7%); predation by chickens (11%) and handpicking (2%). Furthermore, in a few instances, commercially available chemical products were reportedly used to complement the dipping of cattle, in the form of hand sprays, pour-ons and injections with ivermectin (Table 2). Chemical spraying was carried using a 5–10 L hand operated sprayer (2%) or locally fabricated 2 L hand operated sprayers (4%).

Table 2.

Tick control on cattle in communal farming areas of the OR Tambo district of South Africa

| Query | Level | Percentage response per area | Percent of total (n = 94) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inland (n = 65)# | Coastal (n = 29) | |||

| Presence of cattle ticks | Yes | 95 (62) | 93 (27) | 95 (89) |

| No | 5 (3) | 7 (2) | 5 (5) | |

| *Common name of the ticks |

Blue ticks Bont legged ticks |

95 (62) 43 (28) |

93 (27) 83 (24) |

95 (89) 55 (52) |

| *Effects of ticks on cattle |

Weight loss Wounds on body, ears, udder, teat and tail Tick borne diseases Abscesses |

95 (62) 95 (62) 95 (62) 15 (10) |

93 (27) 93 (27) 93 (27) 55 (16) |

95 (89) 95 (89) 95 (89) 28 (26) |

| Loss of appetite | 5 (3) | 7 (2) | 5 (5) | |

| Time of the year with high tick infestations | Summer | 88 (57) | 83 (24) | 86 (81) |

| Winter | 5 (3) | 7 (2) | 5 (5) | |

| Whole year | 3 (2) | 3 (1) | 3 (3) | |

| Note sure | 5 (3) | 7 (2) | 5 (5) | |

| *Tick control methods | Handpicking | 2 (1) | 3 (1) | 2 (2) |

| Predation by chickens | 11 (7) | 14 (4) | 12 (11) | |

| Chemicals (acaricides) | 100 (65) | 100 (29) | 100 (94) | |

| Home-made remedies | 8 (5) | 7 (2) | 7 (7) | |

| *Acaricide application method | Plunge dip | 100 (65) | 100 (29) | 100 (94) |

| Hand spraying | 2 (1) | 17 (5) | 6 (6) | |

| Pour-ons | 14 (9) | 14 (4) | 14 (13) | |

| Injectables | 3 (2) | 17 (5) | 7 (7) | |

| *Facility/equipment used for acaricide application | Dipping tank | 100 (65) | 100 (29) | 100 (94) |

| Hand operated sprayer (5–10 L) | 0 (0) | 7 (2) | 2 (2) | |

| Syringe | 3 (2) | 17 (5) | 7 (7) | |

| Lid-perforated 2 L plastic bottle | 2 (1) | 10 (3) | 4 (4) | |

#Numbers in brackets indicate number of responses

* Several farmers offered multiple responses to the query statement

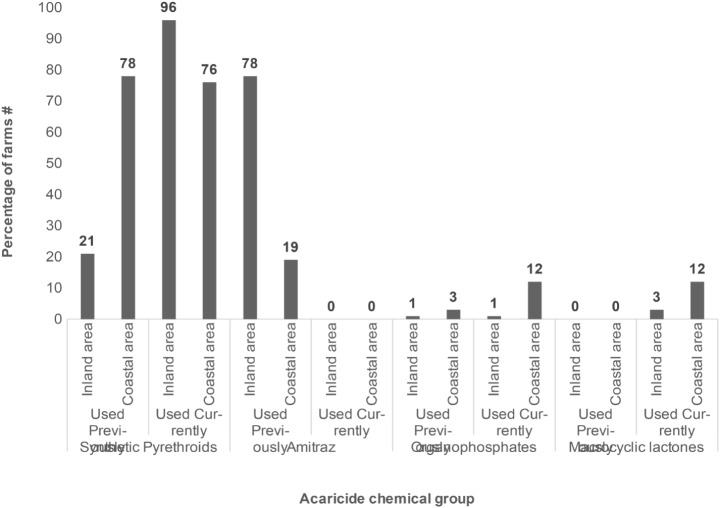

A total of 10 acaricide brands were mentioned to have been used in the control cattle ticks (Table 3). Acaricide formulations, provided by the government that have been used previously in plunge dips at communal farms of the ORTDM included: Triatix® (Amitraz 12.5% m/v, a formamidine), Deca-tix®3 (Deltamethrin, 2.5% m/v, a synthetic pyrethroid) and, Delete-X5® (Deltamethrin, 5% m/v, a synthethic pyrethroid) (Fig. 2). A considerably small number of farms had previously used synthetic pyrethroids (Deadline®) and organophosphates (Supadip®) to complement the government funded dipping services. Deca-tix® and Delete-X5® were more recently being used at 71% and 21% of the inland-located dip tanks, respectively. However, all the coastally located dip tanks were using Delete-X5® (Table 3). To complement cattle dipping, farmers used macrocyclic lactone (ML) and organophosphate (OP) formulations (Fig. 2).

Table 3.

Past and present use of acaricides in the control of ticks on cattle in communal areas

| Query | Level | Percentage response per area | Percent of total (n = 94) | |

| Inland (n = 65)# | Coastal (n = 29) | |||

| *Acaricides previously used | Deca-tix (Plunge dip) | 12 (8) | 76 (22) | 32 (30) |

| Delete -X5 (Plunge dip) | 8 (5) | 3 (1) | 6 (6) | |

| Triatix (Plunge dip) | 80 (52) | 21 (6) | 62 (58) | |

|

Deadline (Pour on) Supadip (Spray) |

2 (1) 2 (1) |

7 (2) 3 (1) |

3 (3) 2 (2) |

|

| Duration of acaricides used previously | ||||

| 1–2 years | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | |

| 2–3 years | 11 (7) | 0 (0) | 8(7) | |

| Above 3 years | 17 (11) | 72 (21) | 34 (32) | |

| Note sure | 70(46) | 28 (8) | 57 (54) | |

| *Names of acaricides in use currently | Deca-tix (Plunge dip) | 71 (46) | 0 (0) | 49 (46) |

| Delete -X5 (Plunge dip) | 29 (19) | 100 (29) | 51 (48) | |

| Deadline (Pour on) | 9 (6) | 7 (2) | 9 (8) | |

| Maxipour (Pour on) | 5 (3) | 3 (2) | 5 (5) | |

| Dectomax (Injectable) | 2 (1) | 7 (2) | 3 (3) | |

| Ecomectin (Injectable) | 0 (0) | 3 (1) | 1 (1) | |

| Virbamec (Injectable) | 2 (1) | 7 (2) | 3 (2) | |

|

Supona aerosol (Spray) Supadip (Spray) |

0 (0) 2 (1) |

7 (2) 10 (3) |

2 (2) 4 (4) |

|

| Duration of acaricides used currently | Less than 1 year | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| 1–2 years | 21 (14) | 3 (1) | 16 (15) | |

| 2–3 years | 2 (1) | 14 (4) | 5 (5) | |

| Above 3 years | 63 (41) | 66 (19) | 64 (60) | |

| Note sure | 12 (8) | 17 (5) | 14 (13) | |

| *Reasons for changing to the currently used acaricides. | AHT advice | 100 (65) | 100(29) | 100(94) |

| Ticks not dying | 74 (48) | 76(22) | 75 (70) | |

|

Poor state of dipping tank Lack/shortage of water |

8 (5) 22 (14) |

10 (3) 35 (10) |

9 (8) 26 (24) |

|

| Reduction in numbers of active ticks on cattle after dipping. | Sometimes | 26 (17) | 24 (7) | 25 (24) |

| No | 74 (48) | 76 (22) | 75 (70) | |

Abbreviation AHT, Animal Health Technician

* Several farmers offered multiple responses to the query statement

#Numbers in brackets indicate number of responses

Fig. 2.

Acaricide chemical groups used on cattle ticks on communal areas in the OR Tambo District of the Eastern Cape province of South Africa. # Percentages were obtained from number of farms that used an acaricide chemical group and total number of farms sampled

It was observed that most farmers (57%) could not remember the exact usage-duration of the previously applied acaricides. However, most of them (64%) reported to have been using the currently applied acaricides for a duration of above 3 years (Table 3). Advice on the rotation or change of acaricide at the farm was mainly provided by the AHT (100%). According to the farmers, the acaricides were changed or rotated because the ticks are not dying (75%). A majority (75%) of farmers reportedly did not observe a significant reduction in numbers of active ticks (feeding and growing) on cattle after several acaricide applications (tick-acaricide control failure).

Farmers’ perceptions on the causes of tick-acaricide control failure

According to the farmers, tick-acaricide control failure could have been caused by a number of factors (Table 4). A majority (76%) of them indicated that the strength of the acaricide mixture inside the dip tank was weak and ineffective in killing ticks. Poor structural state of the dip tanks (42%) and irregular cattle tick control (21%) were also frequently mentioned. They noted that the alleged weak strength of the acaricide mixture in the dip tank might have been as a consequence of mud accumulation (21%) and high water level (14%) after heavy rains (Table 4). Other causes of tick-acaricide control failure mentioned included; limited quantity of the provided acaricide solution, and closeness to the forest. Most farmers (84%) were against the fact that tick-acaricide control failure coincided with the arrival of new animals. Whenever tick-acaricide control failure was observed most farmers (94%) would report and seek advice from the AHT. To reduce or minimize tick-acaricide control failure, farmers demanded for an increase in the strength of the acaricide mixture in the dip tank (85%) or replacement of the acaricide (20%).

Table 4.

Farmers’ perceptions about the causes and management of tick-acaricide control failure on communal areas of the Eastern Cape Province

| Query | Level | Percentage response per area |

Percent of total (n = 94) |

|

| Inland (n = 65)# | Coastal (n = 29) | |||

| * Causes of tick-acaricide control failure | Poor state of dip tank | 28 (18) | 76 (21) | 42 (39) |

| Weak acaricide mixture | 77 (50) | 72 (21) | 76 (71) | |

| Irregular cattle tick control | 22 (14) | 21 (6) | 21 (20) | |

| Mud inside the dip tank | 2 (1) | 21 (6) | 7 (7) | |

| Shortage of acaricide solution | 5 (3) | 7 (2) | 5 (5) | |

| Water level inside dip tank after heavy rains | 0 (0) | 14 (4) | 4 (4) | |

| Closeness to forest | 2 (1) | 3.4 (1) | 2 (2) | |

| Acaricide failure coincides with arrival of new animals | Yes | 19(12) | 10 (3) | 16 (15) |

| No | 81 (53) | 90 (26) | 84 (79) | |

| * Sources of advice whenever acaricide failure is observed | Vet shop teller | 17 (11) | 21 (6) | 18 (17) |

| CAHW/ fellow farmer | 12 (8) | 3 (1) | 10 (9) | |

| AHT | 95 (62) | 90 (26) | 94 (88) | |

| * What should be done when acaricide failure is observed? | Increase the strength of acaricide mixture | 91 (59) | 72 (21) | 85 (80) |

| Use another acaricide | 17 (11) | 28 (8) | 20(19) | |

| Community discusses strategies to curb acaricide failure | Yes | 46 (30) | 35 (10) | 43 (40) |

| No | 54 (35) | 65 (19) | 57 (54) | |

Abbreviations CAHW, Community Animal Health Worker; AHT, Animal Health Technician

* Several farmers offered multiple responses to the query statement

#Numbers in brackets indicate number of responses

Tick-acaricide control application practices

Acaricide solutions provided for by the Eastern Cape Provincial government were supplied to the communal areas through the AHT (95%), CAHWs or dipping committee members (12%). At a few farms (18%), farmers complemented dipping with commercially available acaricide chemical products that were obtained from nearby veterinary drug shops or supermarkets (Table 5). The AHTs (98%) provided advice on all tick control related issues. However, a few farmers consulted the sales persons at drug shops or supermarkets, dipping committee members, or simply relied on their own personal experiences. Often (95%), the mixing of the acaricide solution was conducted by an appointed dipping committee member, most (72%) of whom had received basic training on acaricide application techniques. With regard to acaricide treatment frequency, most cattle (96%) were treated at the recommended rate of 2–4 times per month (24–48 times/year) during the summer. However, during the winter season, irregular acaricide application was rife (91%). It was also noted that most farmers (89%) did not always bring all their cattle for treatment against ticks. Moreover, it was noted that not all (43%) of the newly introduced cattle into the communal area were treated before integrating them with other animals. In communal grazing areas, interactions between cattle and other livestock species including goats, sheep, and horses is inevitable. Consequently, a high level (99%) of interaction between treated cattle and these livestock species was predictable (Table 5).

Table 5.

Tick-acaricide control application practices on communal areas

| Query | Level | Percentage response per area |

Percent of total (n = 94) |

|

| Inland (n = 65)# | Coastal (n = 29) | |||

| *Sources of the acaricides | Vet. drug shop | 14(9) | 14(4) | 14 (13) |

| Supermarket | 5(3) | 3(1) | 4(4) | |

| AHT | 99(64) | 86(25) | 95(89) | |

| CAHWs/ Dipping committee member | 11(7) | 14(4) | 12(11) | |

| *Sources of advice on tick control | Vet. drug shop | 11(7) | 14(4) | 12(11) |

| AHT | 100(65) | 93(27) | 98(92) | |

| Dipping committee member | 1(1) | 3(1) | 2(2) | |

| Personal experience | 1(1) | 7(2) | 3(3) | |

|

Who mixes the acaricides |

Appointed dipping committee member | 95(62) | 93 (27) | 95(89) |

| Cattle owner | 5(3) | 7(2) | 5(5) | |

| Person who mixes the acaricides has been trained | Yes | 66(43) | 86(25) | 72(68) |

| No | 34(22) | 14 (4) | 28 (26) | |

| Acaricide application frequency during summer | 2–4 times per month | 95 (62) | 97 (28) | 96 (90) |

| once a month | 5 (3) | 3 (1) | 4 (4) | |

| Acaricide application frequency during winter | ||||

| Once a month | 0 (0) | 28 (8) | 9 (8) | |

| Inconsistent | 100 (65) | 72 (21) | 91 (86) | |

| Farmers bring all the cattle, always for treatment | Yes | 14 (9) | 3 (1) | 11 (10) |

| No | 86(56) | 97 (28) | 89 (84) | |

| Interaction between treated cattle and other livestock species | Yes | 97 (63) | 100 (29) | 99 (92) |

| No | 3(2) | 0 (0) | 1(2) | |

| Newly introduced cattle into the communal area are treated | Yes | 54 (35) | 55 (16) | 54 (51) |

| No | 45(29) | 38 (11) | 43 (40) | |

| Sometimes | 1(1) | 7 (2) | 3 (3) | |

Abbreviations CAHW, Community Animal Health Worker; AHT, Animal Health Technician

* Several farmers offered multiple responses to the query statement

#Numbers in brackets indicate number of responses

Farm attributes and practices associated with the development of tick-acaricide control failure

There were statistically significant associations (P ≤ 0.05) between rearing of non-descript cattle breeds, alleged weak strength of acaricide mixture inside the dip tank, acaricide treatment frequency during summer, and proportion of farms reporting high tick-acaricide control failure (Table 6). There was insufficient research evidence to associate reported tick-acaricide control failure with geography, failure to treat all cattle in a herd, irregular tick control and poor structural state of the dip tanks (Table 6). An overall proportion of 46.15% and 51.72% of the inland and coastal farms, respectively, reported at least four risky acaricide application practices, which could have resulted into tick-acaricide control failure (Fig. 3). These included the alleged weak strength of the diluted acaricide mixture in the dip tank; irregular tick control; high frequency of acaricide treatment during summer; and failure to treat all cattle in a herd.

Table 6.

Analysis of control malpractices associated with tick-acaricide control failure on communal areas

| Factor | Response level | Tick-acaricide control failure reported on the farm | Fisher Exact probability test value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 70) | No (n = 24) | |||

| Geographical location |

Inland Coastal |

48 22 |

17 7 |

P = 1.00 |

| Cattle breed | *Crossbreeds only | 59 | 4 | P < 0.0001 |

| Local & crossbreeds | 11 | 20 | ||

| Frequency of acaricide treatment in summer | 2–4 times/month | 69 | 21 | P = 0.049 |

| Once a month | 1 | 3 | ||

| Alleged weak strength of the dip solution inside the dip tank | Yes | 61 | 10 | P < 0.0001 |

| No | 9 | 14 | ||

| Failure to treat all cattle in a herd | Yes | 69 | 23 | P = 0.447 |

| No | 1 | 1 | ||

| Irregular tick control | Yes | 64 | 20 | P = 0.271 |

| No | 6 | 4 | ||

| Poor state of dip tank | Yes | 32 | 7 | P = 0.229 |

| No | 38 | 17 | ||

* Crossbreeds of the local Nguni and exotic cattle

Fig. 3.

Proportions of Inland (I) and Coastal (II) communal farms with combinations of risk factors associated with tick-acaricide control failure. A- Alleged weak strength of the dip solution; B- Irregular tick control; C- High acaricide application frequency during summer; D- Failure to treat all cattle in a herd

Discussion

Several farm management and tick control malpractices reportedly associated with increased probability of tick-acaricide control failure have been identified in this study. On communal and commercial (Spickett and Fivaz 1992) farming areas of the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa, rearing of non-descript cattle breeds (mainly Bonsmara) is preferred to the local Nguni cattle. As a result, the herd composition on communal farms is mainly made up of the highly productive and tick-susceptible crossbreeds of the local Nguni and exotic breeds. Therefore, we speculate that the rearing of these cattle crossbreeds is related to the reported tick-acaricide control failure, as they have been found to harbour significantly more ticks (species and numbers) than the local indigenous Nguni cattle breeds (Nyangiwe et al. 2011). Additionally, the Nguni cattle is known for its high adaptability to challenging local environmental conditions, and through natural selection it has acquired a higher degree of tick and disease resistance (Spickett et al. 1989; Norval 1994; Bester et al. 2001). Hence, the keeping of indigenous cattle breed is being promoted as an option for the integrated control of ticks and tick-borne diseases in South Africa (Spickett and Fivaz 1992).

The use of chemical products has been the main control intervention against cattle tick infestations worldwide (Abbas et al. 2014). Plunge dipping of cattle into an acaricide solution is the main control method against ticks and TBDs in communal areas of the ECP (Masika et al. 1997; Moyo and Masika 2009). Dipping of cattle as a tick control method is not effective against ticks in sheltered locations such as between the toes, in the ears, or under the tail (Nicholson et al. 2019). Ticks that are missed, survive to reproduce rapidly and re-establish the pest population. Consequently, in this study farmers reportedly found actively growing ticks on cattle after dipping, and had to supplement the government provided dipping services with chemical acaricide sprays, pour-ons and injections with ivermectin. Nevertheless, the application of acaricides in form of sprays is also regarded as one of the practices that promotes acaricide resistance (Spickett and Firaz 1992). The acaricide spray technique especially when delivered using sub-standard equipment (locally fabricated sprayers), leads to uneven acaricide exposure (Jonsson et al. 2000). This subsequently, leads to an increase in the probability of ticks being exposed to declining acaricide concentrations, thus favouring the selection for resistance. Additionally, the practice of supplementation of the government-provided dipping services entails the adoption of a personal convenient tick treatment strategy, which may involve the use of higher treatment frequencies and doses of chemicals, resulting in the development tick-acaricide control resistance (Kumar et al. 2020).

This study found that synthetic pyrethroids (SP) were the most widely used acaricides in the control of ticks on cattle on the communal areas. This may be attributed to aggressive marketing and broad spectrum of vectors targeted by the chemical (Kumar et al. 2020). Unfortunately, the continuous use and inadequate application of SP over a long period (> 3 years) in communal areas of the ORTDM, could promote the selection of acaricide resistant ticks, thereby increasing the rate of resistance development (de Oliveira Souza Higa et al. 2015), and tick-acaricide control failure. Amitraz (Triatix®), a popular formamidine acaricide of Southern Africa (Rodriguez-Vivas et al. 2018) is no longer in use at dipping tanks on communal farms, probably due to reported tick-acaricide control failure (Strydom and Peter 1999; Mekonnen et al. 2002; Baron et al. 2015) or as a means of implementing acaricide rotation by the provincial government (Vudriko et al. 2018). This study noted an acaricide treatment frequency of 24–48 times/year during summer periods, whereas, dipping was highly inconsistent during winter, ranging from 0–24 times/year. Comparatively, at another communal farming community located at Wartburg of the ECP, dipping was done 24 and 12 times/year during summer and winter periods respectively (Nowers et al. 2013). Meanwhile, on commercial farms of the ECP, most farmers treated their cattle 21–25 times/year while a few treated their animals more than 41 times/year (Spickett and Fivaz 1992). The use of higher acaricide treatment frequencies as noted in the current study, is a likely indicator of tick control challenges (Spickett and Fivaz 1992). This practice increases the selection pressure on ticks over time, leading to the development of acaricide resistance (Rodriguez-Vivas et al. 2018). The probability of ticks developing resistance is higher when acaricides are used more than 5 times/year (Jonsson et al. 2000). Sutherst and Comins (1979) has recommended an acaricide treatment frequency of 16 times/year, especially during spring or early summer periods when a large proportion of tick populations are in the parasitic stage.

In this study, the alleged use of lower acaricide dosages for tick control at the dipping tanks was statistically associated with proportion of farms reporting tick-acaricide control failure. In a similar vein, Mekonnen et al. (2002) had indicated that the use of incorrect acaricide concentrations is one of the most important factors affecting the efficacy of acaricides at communal dipping tanks of the ECP. Although the mixing and replenishment of the dipping tanks was reportedly conducted by trained individuals, measurement errors could have led to inappropriate acaricide doses (Mekonnen et al. 2002). However, the alleged weak strength of the dip solution probably could have arisen from shortages in the government provided acaricides, mud accumulation and high water level inside the dipping tank after heavy rains. The exposure of ticks to lower acaricide doses favours the selection of resistant individuals (Kemp and Kunz 1994) and consequently to tick-acaricide control failure. Therefore, for optimal tick control on cattle that would lessen the effects of tick-acaricide control failure, farmers commanded for the application of higher acaricide doses. This finding corroborates that of Mekonnen et al. (2002), where farmers demanded for an increased in acaricide concentration in the dip tank during the peak tick season. However, when considering the selection pressure that may have already been imposed by the application of lower acaricide doses, any increase in the acaricide dosage would result in a rapid development of resistance (Kemp and Kunz 1994). Nevertheless, even if the high-dose strategy was to be considered, there would possibly be some limitations on their use including, uncertainties regarding the exact dose required to kill resistant ticks, restrictions related to the approved dosage for the product as well as animal and environmental safety issues (George et al. 2004).

It is interesting to note that the reported tick-acaricide control failure in the ORTDM could have been as a function of a whole set of acaricide application practices. For instance, approximately 50% of the communal farms exhibited combinations of at least four inappropriate control practices, including the alleged weak strength of the dip solution, irregular tick control, high acaricide treatment frequency, and failure to treat all cattle in a herd. Other sub-optimal tick control practices that predispose to tick- acaricide failure included poor structural state of the dip tank and incorrect rotation of acaricide. In addition, the fact that farmers could not remember the exact duration of acaricides used previously, probably also has an implication on the correctness of acaricide rotation. This study also noted that communal farmers generally practiced mixed livestock farming with cattle and other livestock combinations, mostly including sheep, goats and horses. These animals are alternative hosts to cattle tick species (Horak et al. 2018). Therefore, they should be considered together with cattle with regard to the control and eradication of tick species. Furthermore, it would be of interest to explore the reasons why communal farmers treated ticks on cattle at irregular intervals. We suggest that the encountered tick-acaricide control failure probably might have discouraged some farmers from participating in dipping programs. Nevertheless, irregular dipping of animals could have been due to shortages in acaricide solution or lack of water to replenish the dip as a result of drought (Eisler et al. 2003), farmers making use of other control options (Moyo and Masika 2009), elderly cattle owners’ inability to walk long distances for cattle treatment (Sungirai et al. 2016) and, the lack of repairs or structural maintenance of dip tanks (Eisler et al. 2003).

A limitation to this study include the purposive selection criterion that was used for the sampling of participatory farms. Such a criterion might have limited the ability to make generalisations on tick-acaricide control failure, as farms with smaller herd sizes (< 1000) were excluded. Additionally, a few pre-selected farms were excluded as they were not easily accessible. To limit this, questions were constantly evaluated and interpreted to be sure that they were understood correctly. The study was unable to verify the possible contribution of poor acaricide quality on the reported tick-acaricide control failure. Furthermore, the study did not undertake morphological or molecular identification of the tick species present on cattle. This is a crucial omission since different tick species may necessitate distinct strategic control measures.

Conclusion

This survey confirms that prolonged and frequent exposure of ticks to inappropriate doses of the same acaricide chemical compound, leads to increased probability of tick-acaricide control failure, possibly due to emergence of tick acaricide resistance. Additionally, the likelihood of tick-acaricide control failure problem on communal areas of South Africa is expected, as approximately 50% of farms display combinations of at least four tick control malpractices. Nevertheless, the reportedly high rate (75%) of tick-acaricide control failure on communal farms should be investigated further to ascertain the manifestation of resistance development. Acaricide control failure management strategies should include educating field veterinarians and farmers on acaricide use and resistance in ticks to these chemicals. Farmers are urge to use acaricides strategically and judiciously, focusing on targeted applications in farms or areas where tick populations are concentrated. Furthermore, field veterinarians should be encouraged to identify and report tick-acaricide control failure promptly for early diagnosis, to promote the sustainability of the currently available acaricide chemical formulations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to recognize the contribution and efforts of the District Veterinary Service officials, Animal Health Technicians, Community Animal Health workers and cattle farmers from various towns/villages within the OR Tambo District Municipality for providing all necessary information and assistance during the administration of questionnaires.

Author contributions

W.D.D.: Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, resources, funding acquisition, and original draft preparation. P.V.: Supervision. O.T.: Conceptualization, supervision, resources, funding acquisition. All authors edited and reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

The Directorate of Research Development and Innovation of the Walter Sisulu University (WSU) provides partial funding towards the project. The NRF incentive fund for rated researchers (GUN:118949) made available to Oriel Thekisoe was also used in this study.

Open access funding provided by North-West University.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethical approval

To ensure compliance with ethical standards, animals were treated with care and respect, and all procedures were approved by the Faculty of Natural Sciences Committee at the North-West University. Project Reference Number: NWU-02103-19-A9.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Abbas RZ, Zaman MA, Colwell DD, Gilleard J, Iqbal Z. Acaricide resistance in cattle ticks and approaches to its management: the state of play. Vet Parasitol. 2014;203(1–2):6–20. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2014.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron S, van der Merwe NA, Madder M, Maritz-olivier C (2015) SNP analysis infers that recombination is involved in the evolution of amitraz resistance in Rhipicephalus microplus. PLoS ONE 10:e0131341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bester J, Matjuda LE, Rust JM, Fourie HJ (2001) The Nguni: A Case Study in Proc. Community-Based Management of Animal Genetic Resources, Mbabane

- de Oliveira Souza Higa L, Garcia MV, Barros JC, Koller WW, Andreotti R. Acaricide Resistance Status of the Rhipicephalus microplus in Brazil: A literature overview. Med Chem. 2015;5:326–333. doi: 10.4172/2161-0444.1000281. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eisler MC, Torr SJ, Coleman PG, Machila N, Morton JF. Integrated control of vector-borne diseases of livestock–pyrethroids: panacea or poison? Trends Parasitol. 2003;19:341–345. doi: 10.1016/S1471-4922(03)00164-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George JE, Pound JM, Davey RB. Chemical control of ticks on cattle and the resistance of these parasites to acaricides. Parasitology. 2004;129(Suppl S1):S353–S366. doi: 10.1017/S0031182003004682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goni S, Skenjana A, Nyangiwe N. The status of livestock production in communal farming areas of the Eastern Cape: a case of Majali Community, Peelton. Appl Anim Husb Rural Develop. 2018;11:34–40. [Google Scholar]

- Horak IG, Heyne H, Williams R, Gallivan GJ, Spickett AM, Bezuidenhout JD, Estrada-Peña A. The Ixodid ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) of Southern Africa. Gewerbestrasse: Springer; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- IDP (2017) Integrated Development Plan, O. R Tambo District Municipality. Mthatha, Eastern Cape Province

- Jonsson NN, Mayer DG, Green PE. Possible risk factors on Queensland dairy farms for acaricide resistance in cattle tick (Boophilus microplus) Vet Parasitol. 2000;88:79–92. doi: 10.1016/S0304-4017(99)00189-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R, Sharma AK, Ghosh S. Menace of acaricide resistance in cattle tick, Rhipicephalus microplus in India: Status and possible mitigation strategies. Vet Parasitol. 2020;278:108993. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2019.108993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunz SE, Kemp DH. Insecticides and acaricides: resistance and environmental impact. Rev Sci Tech off Int Epiz. 1994;13(4):1249–1286. doi: 10.20506/rst.13.4.816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masika P, Sonandi A, Van Averbeke W. Tick control by small-scale cattle farmers in the central Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. J S Afr Vet Assoc. 1997;68:45–48. doi: 10.4102/jsava.v68i2.868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mekonnen S, Bryson NR, Fourie LJ, Peter RJ, Spicketi AM, Taylor RJ, Strydom T, Horak IG. Acaricide resistance profiles of single- and multi-host ticks from communal and commercial farming areas in the Eastern Cape and North-West provinces of South Africa. Onderstepoort J Vet Res. 2002;69:99–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyo B, Masika PJ. Tick control methods used by resource-limited farmers and the effect of ticks on cattle in rural areas of the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2009;41:517–523. doi: 10.1007/s11250-008-9216-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musemwa L, Mushunje A, Chimonyo M, Mapiye C. Low cattle market off-take rates in communal production systems of South Africa: causes and mitigation strategies. J Sust Dev A. 2010;12(5):209–225. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson WL, Sonenshine DE, Noden BH, Brown RN (2019) Ticks (Ixodida). In Gary M, Durden LA (ed) Medical and Veterinary Entomology (Elsevier), pp 603–672, 10.1016/B978-0-12-814043-7.00027-3

- Norval RAI. Vectors: ticks. In: Coetzer JAW, Thomson GR, Tustin RC, editors. Infectious diseases of livestock with special reference to Southern Africa Vol. Cape Town: Oxford University Press; 1994. pp. 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Nowers C, Nobumba L, Welgemoed J. Reproduction and production potential of communal cattle on sourveld in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. AAH RD. 2013;6:48–54. [Google Scholar]

- Ntondini Z, van Dalen EM, Horak IG. The extant of acaricide resistance in 1-, 2-, and 3-host ticks on communally grazed cattle in the eastern region of the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. J S Afr Vet Assoc. 2008;79(3):130–135. doi: 10.4102/jsava.v79i3.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyangiwe N, Goni S, Hervé-Claude LP, Ruddat I, Horak IG. Ticks on pastures and on two breeds of cattle in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Onderstepoort J Vet Res. 2011;78(1):320–328. doi: 10.4102/ojvr.v78i1.320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Vivas RI, Jonsson NN, Bhushan C. Strategies for the control of Rhipicephalus microplus ticks in a world of conventional acaricide and macrocyclic lactone resistance. Parasitol Res. 2018;117:3–29. doi: 10.1007/s00436-017-5677-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spickett AM, Fivaz BH. A survey of cattle tick control practices in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa. Onderstepoort J Vet Res. 1992;59:203–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spickett AM, de Klerk D, Enslin CB, Scholtz MM. The resistance of Nguni, Bonsmara and Hereford cattle to ticks in a bushveld region of South Africa. Onderstepoort J Vet Res. 1989;56:245–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statements & Declarations

- Strydom T, Peter R. Acaricides and Boophilus Spp. resistance in South Africa. In: Morales G, Fragosa H, Garcia Z, editors. Control De La Resistancia en Garrapatas Y Moscas De Importancia Veterinaria Y Enfermedadas que transmiten. Jalisco: IV Seminario Internacional de Parasitologia Animal. Puerto Vallarta, Mexico; 1999. pp. 35–40. [Google Scholar]

- Sungirai M, Moyo DZ, De Clercq P, Madder M. Communal farmers’ perceptions of tick-borne diseases affecting cattle and investigation of tick control methods practiced in Zimbabwe. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2016;7:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2015.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherst RW, Comins HN. The management of acaricide resistance in the cattle tick, Boophilus microplus (Canestrini) (Acari: Ixodidae), in Australia. Bull Entomol Res. 1979;69:519–537. doi: 10.1017/S0007485300019015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vudriko P, Okwee-Acai J, Byaruhanga J, Tayebwa DS, Okech SG, Tweyongyere R, Wampande EM, Okurut ARA, Mugabi K, Muhindo JB, Nakavuma JL, Umemiya-Shirafuji R, Xuan X, Suzuki H. Chemical tick control practices in southwestern and northwestern Uganda. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2018;9(4):945–955. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2018.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.