Abstract

Climate concern is on the rise in many countries and recent research finds that lifestyle- and behaviour-change could advance climate action; yet, individuals struggle to move their climate concern into action. This is known as the ‘awareness-action inconsistency,’ ‘psychological climate paradox,’ or ‘values-action gap.’ While this gap has been extensively studied, climate action implementation and policy-design seldom sufficiently apply that body of knowledge in practice. This Perspective presents a comprehensive heuristic to account for how individuals bring climate change into their awareness (climate action-logics), how they keep climate change out of their awareness (climate shadow), how social narratives contribute to shaping choices (climate discourses), and how systems and structures influence and constrain agency (climate-action systems). The heuristic is illustrated with an example of 15-Minute Cities in Canada. Understanding the multifaceted dilemma that weighs on people’s sense-making and behaviours may help policy-makers and practitioners to ameliorate the climate awareness-action gap.

Keywords: Behaviour change, Climate communications, Climate engagement, Climate shadow, 15-Minute cities, Values-action gap

Introduction

What holds societies back from reaching their climate targets has become a focus of study in the social sciences. Despite rising climate concern worldwide, most countries are not set on trajectories in which climate targets will be met by 2050 (O’Brien 2018; Hatch 2021; Matthews and Wynes 2022; Leiserowitz et al. 2023). A substantial constraint on government’s ability to accelerate climate action is due to lack of behavioural change and public acceptance of climate policies (Wang et al. 2018). On the one hand, IPCC (2022) reports that changes to lifestyles and behaviour have significant potential for large reductions in global greenhouse gas emissions. Yet, on the other hand, “in practice, human behaviour is as complex as the phenomenon of climate change” (Rishi 2022, p. 147) and consideration of the psychosocial dimensions of climate change are not well integrated into climate action plans (Hochachka et al. 2022). Despite widespread concern regarding climate change, climate-relevant behaviors can be enmeshed with mindsets, emotions and culture, and seldom does policy design account sufficiently for the social complexity surrounding the sought-after behaviour- and systems-change.

This delayed progress on climate action is partially explained by the gap between climate concern and the uptake of climate actions in daily lives (Matthews and Wynes 2022). This gap is referred to as an “awareness-action inconsistency” (Rishi 2022, p. 147), the psychological climate paradox (Norgaard 2011; Stoknes 2014), the attitude-action gap (Kollmuss and Agyeman 2002), and the values-action gap (Blake 1999). All of these terms highlight that even with climate concern in place to support action, in many instances climate action still does not emerge. It is important to better understand what is occurring in this gap. Misunderstandings about human perceptions and behaviour can lead to ineffective or misguided policies (Clayton et al. 2015), and can also inflame opposition and conflict about climate goals that further delays climate action. In their study of UK workers regarding net-zero strategies, Sawas et al. (2023, p. 7) note that “political polarisation is on the rise, globally, so meaningful engagement is also vital to mitigate backlash and unintended consequences of implementing the ambitious policies we need to meet our net zero policies.” Research on the disconnect between climate awareness and action has examined values, political ideology, emotions, attentional dynamics, lack of trust, and perceived locus of control, and more. However, it can be difficult for practitioners to parse through this information to accurately diagnose what is occurring in a given situation or context and then to identify possible ways to address it. Practical yet comprehensive models that support actors in climate communications, engagement, and policy-design are hard to find,1 and governments and policymakers can struggle to know what is most important to address in fostering greater support for climate action. As it stands, how to close the climate values-action gap remains an urgent, unsolved puzzle.

In addressing this puzzle, it is important to consider both the individual- and structural-factors involved in responding to climate change. Individual-factors include the emotions, political ideologies, and competing values which relate with how knowledge and concern are moved into action (Stoknes 2014), as well as the human agency to indeed act carried by the belief that such action will result in intended outcomes (McLaughlin and Dietz 2008; Brown and Westaway 2011). Structural-factors include the power asymmetries in decision-making, impacts, and costs, as well as the systemic constraints on lifestyles and low-carbon choices (Giddens 1986; Burns and Dietz 1992; Shove et al. 2012). On the one hand, individual agency can shape social structures through consumer choices, voting preferences, and social signalling (Naito et al. 2022). On the other hand, social structures heavily influence the choices and decisions that individuals are able to make, and without a sense that their actions will produce desired changes, individuals tend to have little incentive to act at all (Bandura 2000, 2006; Seto et al. 2016). As such, the structure-agency tension is central to understanding the values-action gap. Focusing just on individuals’ contributions to climate change, may risk leaving unexamined the ways in which institutions shape everyday life (Maniates 2001; Shove 2010) and may miss the more significant emissions contributions from the capitalist, industrial socio-political system (Klein 2015; Castree 2016). Yet a structural lens on climate action alone says little about how to account for the psycho-social dimension of individuals (O’Brien 2018; Brulle and Norgaard 2019; Leichenko and O’Brien 2019). A hidden assumption of essentialism, that persists in the field of climate change, has been found to discount the role of agency and culture and led to a bias towards technological solutions for climate action (McLaughlin and Dietz 2008).

Adjusting for that bias, I emphasize the psycho-social aspects here, but seek to employ an integrated framework that includes structural aspects. Both are important and inextricably linked. For example, while structures exert influence on individuals, individuals in turn shape the very systems that surround them, through their support of pro-climate policies, voting preferences, advocacy, forms of leadership, creativity, and agency to enact their own pro-climate behavioural changes and/or to champion pro-climate systems- and cultural-changes in their regions. For example, Kitt et al. (2021) note the psychological and affective factors, like positive emotions and trust, that affect citizen’s acceptance of climate policies. Furthermore, as sense-making in the current post-truth social context becomes more turbulent, with for example the rise of polarization and risks to democracy (McKay and Tenove 2021), what could have been social tipping points for net-zero structural change (Otto et al. 2020), risk becoming social stalling points (Linsell 2024). The objective of considering these psycho-social dimensions of climate action is not to assign blame to individuals and thus avoid structural change (Shove et al. 2012; Schiffman 2021), but rather to better grasp the ways in which psychology, ideology, emotional reactions, economic and cultural traumas, and so forth, factor into to both individual- and structural-change, since transformations emerge from the interaction between them (Giddens 1986; O’Brien 2015; Naito et al. 2022).

In this article, I present an integral heuristic to understand what is occurring within this awareness-action gap, including climate action-logics, climate shadow, climate discourses, and climate-action systems. These are defined and described below. Due to the larger extant body of work addressing the narrative and structural dimensions of climate action, I further center my focus on the lesser-attended psychosocial aspects or the ‘personal sphere’ (i.e. subjectivities, values, and worldviews) (O’Brien 2018; Wamsler and Raggers 2018; Wamsler et al. 2020). For example, certain recent emergent phenomena with overt consequences for climate agenda—namely, the rise of populism and the increase of polarization—need to be understood in both their psycho-social and structural dynamics, and yet have to date received insufficient attention by policymakers or environmentalists in understanding their origins or processes (Graves and Smith 2020; McKay and Tenove 2021). I build on preliminary research into action-logics applied to climate change and also develop the novel concept of climate shadow, which may provide new ways to understand and address root causes of climate opposition and inaction. Finally, I apply this heuristic with an example of the 15-min cities urban planning tool from Western Canada, including implications for climate change communications and engagement. An assumption held in this paper is that if climate policies and engagement were designed to better account for all four dimensions of this heuristic, pro-climate behaviour and lifestyle changes with significant potential to lower greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions may be more likely to be achieved.

Background

Individuals have an important role in mitigating climate change, through changes in lifestyles and behaviours (Dubois et al. 2019; IPCC 2022). This can occur through private actions (i.e. pro-environmental buying choices, creativity, agency), social-signalling actions (i.e., voting preferences, social (dis)approval of certain practices and policies), and systems-changing actions (i.e. advocacy for pro-climate policies and systems) (Naito et al. 2022). Climate action plans, however, seldom sufficiently consider the personal and structural transformations that support such behavioural and lifestyle changes (Hochachka et al. 2022; Revez et al. 2022). The result is that, even when people are concerned about climate change, often pro-climate actions still do not occur. Says Rishi (2022, p. 148):

Going deeper into the interrelationship between thought processes and climate action, one of the most common observations is that many of the times we have clear understanding of the likely negative impacts of climate change or unsustainable behavioural practices, we still refrain from taking desirable actions at the behavioural level. Why it is so?

Research has found communicative, cognitive, emotional and systemic reasons for this. In terms of communication, the linear ‘knowledge-deficit’ model—which assumes that more knowledge or information would be sufficient to ignite broad, widespread behaviour, systems and culture shifts to occur—has been found insufficient as a theory of change (Shove 2010; Suldovsky 2017) yet climate communications frequently default back to it (Perga et al. 2023). Emotional and ideological processing go into people’s attention on climate change, which already is competing for room in a crowded media landscape (Luo and Zhao 2019; Wynes et al. 2020). People tend to employ motivated reasoning in their media consumption about climate change (Kahan 2015; Luo and Zhao 2019). Reporting on climate change often occurs in an inflammatory manner, using frames like doom, gloom, sacrifice, and fear, which can create rebound-effects that counteract engagement (Stoknes 2014). Perga et al. (2023, p. 1) argue the current “mediatization of climate change research fails to breed real society engagement in actions.” In a post-truth context, the primacy of scientific truth has been replaced by a broad array of subjective truths based on emotions, identity, and prior personal experience, made even worse by algorithmic polarization (Moezzi et al. 2017; Groves 2019). As a result of how climate change has been communicated, it is now a politicized and emotional issue for many people, and sense-making about it can be difficult (Martel-Morin and Lachapelle 2022). Experts assert that losing the public narrative, risks losing the policies, in what has been referred to as greenlash (i.e. backlash to climate policies) (Clarke 2023).

Cognitively, the hyper-complexity of climate change results in markedly different mental models and understandings about it. Wynes et al. (2020) find that because climate impacts cross domains and involve multiple systems, individuals’ are limited in evaluating their own carbon footprints, and can tend to over- or under-estimate the climate impacts of certain decisions. The slow and, to date, largely ineffective responses to climate change is also related with an inability to collectively imagine the reality and severity of climate risks nor the potential solution pathways and desirable futures (Milkoreit 2017). The multifaceted nature of the climate crisis means that it cannot necessarily be solved through simply exchanging one set of practices with another (such as, switching from driving fossil fuel-powered cars to electric vehicles); rather the climate challenge involves trade-offs and paradigmatic shifts (Gram-Hanssen 2019). High cognitive demands further make climate change vulnerable to certain psychological barriers, such as Gifford’s (2011) ‘seven dragons of inaction’ (i.e. limited cognition, ideologies, comparisons with others, sunk costs, discredence, perceived risks, and limited behaviour).

When projections of climate impacts present a bleak future, involving loss of things we value and requiring sacrifice and disruption to the current system, emotionally, people may seek ways out of having to bear climate change in mind (Norgaard 2006b). The broad, disruptive changes to society and strong governmental regulatory response, is perceived by many as threatening (Graves and Smith 2020), and “affective processes motivate or prevent people from climate-friendly action” (Harth 2021, p. 140). Climate change can evoke feelings that are ego-dystonic, that is, out of alignment with who one believes oneself to be in terms of self-identity, culture, ideology, or faith (Norgaard 2006a, 2006b, 2011). It can also provoke a feeling of ontological insecurity—or, an insecure sense of nation-state, environment, or that which can be relied upon (Giddens 1991; Harries 2008; Hamilton 2017). Facing climate predictions, some find it hard “to believe that life will continue in much the same way as it always has” (Harries 2008, p. 482), others feel a sense of threat to “our deep and normalized conceptions of humanity and what it means to be a human ‘self’ in a stable and continuous world” (Hamilton 2017, p. 579). People tend to push such unmanageable feelings and painful information out of their conscious mind as ‘shadow’ in psychological terms (Freud and Bonaparte 1954). In a context of the IPCC (2021) report, Rishi (2022) refers to this psychological phenomenon of shadow regarding feelings of helplessness when climate impacts are presented alongside few to no actions people can effectively take to lessen those risks. I develop the novel concept of ‘climate shadow’ further here, explaining it as an ego-defence mechanism to safeguard the self against negative emotions about climate impacts (or about climate action itself) that are too difficult for the self to manage (further description below). In a blog article, Pattee (2021) referred to the term climate shadow in a conceptually different manner—referring to the total carbon emissions that an individual accrues and carries implicitly—like a literal carbon shadow following them around. Whereas here, my manner of using the term proceeds, like Rishi (2022), from the discipline of psychology.

Systemic reasons for the awareness-action gap relate to the fact that society is not well set-up for pro-climate choices to be the default options for people. While many nations are engaging in net-zero transitions in some form or another, typically taking up a new pro-climate practice usually means ‘going against the grain’ of the status-quo systems in which one lives. Often the behaviour change comes at an expense to individuals—in terms of increased costs, upfront investment, and radical changes to culture and lifestyles—some of which are borne disproportionately by certain groups in society. Such power asymmetries (i.e. between the decision-makers and those who bear the consequences of decisions) require an equity and justice lens to better account for fairness, as well as more deeply democratic processes for how governments involve local actors in climate action planning, including the need to reweight the reliance on certain knowledges over others (Gram-Hanssen et al. 2021). Shove (2010, p. 1281) describes how the focus on individual behaviour change is limited in so far as it fails “to be explicit about the extent to which state and other actors configure the fabric and the texture of daily life.” Multi-scalar social-ecological processes can serve as limitations or opportunities for individual’s agency to act on climate change (Nightingale 2015; Greene et al. 2022); sustainable patterns of behaviour are shaped—or not—through changes that occur structurally. At present, socio-technical systems of modern life are largely set on paradigms of fossil fuel use, as well as high consumption, resource extraction, pollution, and waste (Geels et al. 2004). Making choices that run counter to that can be hard to prioritize in the current system and existing cultural norms (Hochachka and Mérida 2023). Pro-climate options are generally not yet the easier, more convenient, effective, and cheaper options, in large part due to the way systems are structured; even willing consumers can find their agency constrained and their lifestyles ‘locked-in’ to high-carbon practices (Sanne 2002).

These communicative, cognitive, emotional, and systemic challenges of climate change all contribute to the awareness-action gap. However, an applied integration of this research into climate policy design and engagement is seldom carried out. Climate change is still presented by environmental groups, media, and the government via frames that are known to have limited impact if not boomerang effects (Perga et al. 2023). Climate policies are designed in ways that do not take a full account of the psychological and emotional tasks that climate change requires (Pidcock et al. 2021). Climate public-engagement is included in climate action plans (often under Article 12 of the Paris Agreement—‘Action for Climate Empowerment’), yet there is limited evidence that this is actually occurring, and when it does, typically it is often oriented towards getting citizens on-board with politically-mandated climate action, rather than oriented towards mobilizing a bottom-up social mandate for such action (Sawas et al. 2023). Finally, insufficient structural analysis is brought to bear on the systems-change that is central to effective climate action, resulting in plans that can fall short of reaching net-zero ambitions.

The following integral, transdisciplinary heuristic presents a way to think about the complex sensemaking challenges that individuals and groups experience, which are key for successful climate action and could be better incorporated into climate policy design and engagement.

A new heuristic to understand the awareness-action gap

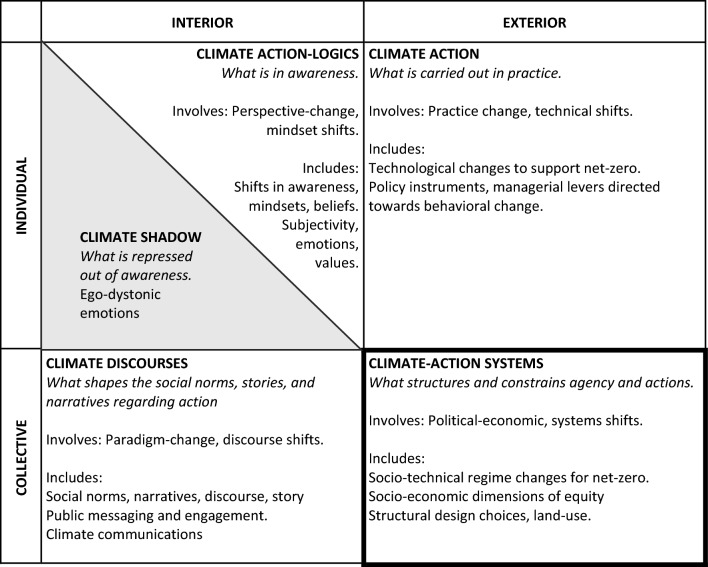

Drawing together the above diverse literature and empirical research, the below heuristic integrates four primary aspects involved in climate awareness moving into action: (1) how people become aware of climate change, (2) how people seek to stay unaware about climate change, (3) how narratives and stories influence their views and actions on climate, and (4) how the systems in which they live shape and influence their ability to act on their awareness (Fig. 1). This is based on the quadrants of Integral Theory (Wilber 1996, 2001; Esbjorn-Hargens 2009), applied in ecology and sustainability (Esbjorn-Hargens and Zimmerman 2009), climate change adaptation (Esbjörn-Hargens 2010; Hochachka 2021; O’Brien and Hochachka 2010), and climate policy design (Hochachka and Mérida 2023). These comprise an important set of interactions that are at play in the awareness-action gap.

Fig. 1.

An integral heuristic to understand psycho-social and structural aspects that contribute to the climate awareness-action gap. The four quadrants delineate the interior (subjective) and exterior (objective) dimensions of individuals and collectives. Climate Action includes the technical or managerial levers and policy instruments to nudge behaviours. The lower-right Climate-Action Systems (i.e. built environment, institutions, development paradigms) exert significant influence in shaping and constraining individuals’ agency (i.e. weighted line indicates this weighted influence). The upper-left includes Climate Action-Logics, which are the meaning-making frames through which people interact with their world (i.e. what is in people’s awareness) and Climate Shadow which refers to the ego-dystonic emotions that are repressed outside of conscious awareness. Climate Discourses refer to collectively held narratives and stories that afford social meaning to climate action

This heuristic is presented as a mental-model or thinking tool that could be brought into various aspects of the design and implementation of climate action; such as for designing public engagement processes, in creating communication materials about climate action (i.e. considering hot and cold buttons for residents), and when doing vulnerability-informed surveys or stock-taking about a region and its population. While any framework or heuristic has limitations, practitioners nevertheless employ mental models in their design of plans and strategies. This heuristic is best held lightly and reflexively—not as a ‘silver bullet’ nor as one that is fixed—but that could be used by climate practitioners to sort the complexity of the sensemaking challenges that publics face regarding climate. The categories of the heuristic are ‘empty of content’ until they become animated in a context, through the lived-realities of people, communities, and place. Pörtner et al. (2023, p. 7) reflect on the need for these types of frameworks that are “universal in terms of intent but sufficiently flexible and adaptive to different socioecological contexts, including historically and culturally embedded institutional and political governance structures.” This heuristic has been used by climate actors in the public, non-profit and academic sectors in Vancouver, BC in a focus group, for understanding psycho-social and structural dimensions of climate engagement.

First, I consider the ways in which people make meaning of climate change, which relates with what actions in turn make sense to them. These are referred to as climate action-logics (Lynam 2012; Divecha and Brown 2013; Hochachka 2019; Pender 2023). The term ‘action-logic’ is drawn from developmental psychology to describe an internal mechanism by which people interpret their surroundings and craft their actions or reactions (Bradbury 2015; Rooke and Torbert 2005). This body of work explains how people bring climate change into their awareness.

Second, due to how complex, politicized, and emotional climate change can be (Hulme 2009; Stoknes 2014), people can tend “to selectively interpret the ‘facts’ in ways that do not threaten their prior beliefs, values, and identities” (Martel-Morin and Lachapelle 2022, p. 6). Sometimes people do not want to see or accept that climate change is occurring because of the strong emotional ramifications of what it would mean if it were, in terms of climate impacts or the disruption in society for mitigation and adaption. Strong emotions can also arise in response to climate regulations or mandates by the government; without a sense of being heard and accounted for in these public initiatives, those emotions can fester and fuel opposition to governmental climate response. For example, individuals can feel defensive when interacting with municipal staff, they may feel blamed, forced to provide their personal information or to engage with decision-makers in ways that amplify power asymmetries (Nightingale 2015, 2017; Wamsler and Raggers 2018). When such strong emotions about climate change are pushed, repressed, or somehow maintained out of one’s awareness they can become climate shadow. This is a new term I introduce in this paper referring to a psychological defense mechanism in which a person avoids feelings that are ego-dystonic—that is, repugnant or at variance with one’s sense of self—by making them shadow.

Third, the shared cultural background, narratives, and stories told about nature/environment/climate contribute to shaping both individual consciousness as well as shaping the systems of a society (e.g., the ‘stories’ that are told about the economy, and therefore the economic policies that get put in place). Climate discourses, which are related to, but distinct from, action-logics, refer to this communicative dimension of climate action, including hermeneutics, narratives, social norms, and culture (Leichenko and O'Brien, 2019). The importance of climate discourses can be seen in the research on how important it is to get climate information from trusted sources and thought-leaders in one’s social group (Stoknes 2014) as well as regarding mis/disinformation about climate in a post-truth context (Groves 2019).

Fourth, I consider the ways in which actions are shaped by the structures and systems in which one lives. Referred to as climate-action systems, this section deals with what people can actually do in regards to the things they are aware of and concerned about, focusing particularly on how societal systems and structures support or thwart, incentivize or limit, people from acting on their awareness. Giddens (1986, p. 169) describes how structure (the rules and resources encoded into societal systems) is “always enabling and constraining, in virtue of the inherent relation between structure and agency.” The two-truths of that statements are both exciting and sobering; exciting in so far as a broad structural change towards low-carbon lifestyles can indeed enable similarly broad behavioural changes by individuals (relatively independent of their individually-sourced preferences, values, and so forth); yet sobering in that the high-carbon status-quo development essentially constrains individuals into similarly high-carbon practices. Systems and structures are, as such, ‘heavy’, meaning that they have an inordinate influence on individuals, including shaping social ideologies and consciousness of a culture (Wilber 2006). Critical theory, Marxist social theory, and political ecology all point to the outsized influence of systems on individual’s choices, as well as the equity and inclusion concerns that are woven with this dimension of the heuristic. It is an essential consideration of what drives and generates the awareness-action gap.

The interplay of these dimensions is crucial for addressing the awareness-action gap regarding climate action. How people, individually and collectively, resolve the dilemma presented by these four dimensions will support their ability to bridge the awareness-action gap and effectively carry out climate action. Below, I describe these four aspects in turn.

Climate action-logics

Awareness is important, as it is considered a first step in perception being created (Madhuri and Sharma 2020). How people become aware and make meaning of climate change is an important driver as to why and how they might take action on it.

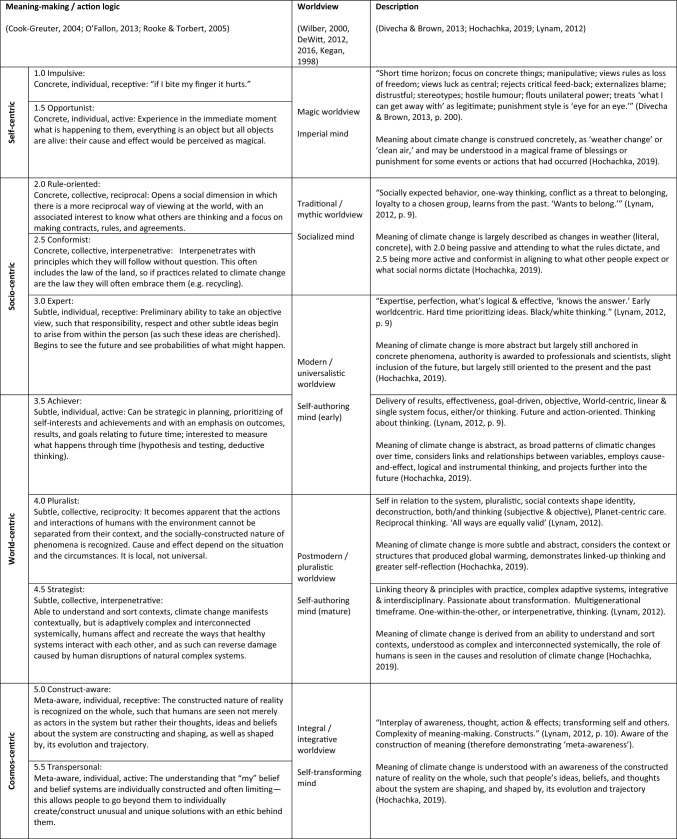

‘Action-logic’ is a term in psychology, defined as the psychological activity by which people organize their understanding about the world.2 Action-logics, as described by Rooke and Torbert (2005), operate in a paradigm-like fashion, as frames through which individuals interpret and organize meaning about their internal and external experience (Jones 2016). Applied here to understand climate responses, climate action-logics refer to the ways in which people become aware of climate change and what meanings they hold about it (Table 1). The study of action-logics in adult developmental psychology research has been applied in leadership, business, organizational development, and education (Kegan and Lahey 2001, 2009; Rooke and Torbert 2005), as well as in sustainability work and climate change (Lynam 2012; Divecha and Brown 2013; Hochachka 2019; Pender 2023).

Table 1.

Climate action-logics (adapted from Hochachka 2019)

This body of research finds that action-logics inform and drive human reasoning and behavior (Torbert et al. 2004; Cook-Greuter 2013). Action-logics are related with other aspects of psychology—typically one becomes aware of something before they value or create morals and beliefs about it (Hedlund-de Witt 2012; Lynam 2019; Wilber 2000). Action-logics inform how one interprets reality and what one cares about, are related with worldviews and values, and can inform important standards or life goals (Rokeach 1973) and environmental attitudes (Schultz 2001). The coordination of meaning changes through lifespan towards greater degrees of complexity, with each new action-logic transcending and including the previous stage (Cook-Greuter 2013). Through this process, not only do the contents of what one is aware of increase, but also the manner of how meaning is organized becomes more complex. Kegan (2002, p. 148) describes how, “what gradually happens is not just a linear accretion of more and more that one can look at or think about, but a qualitative shift in the very shape of the window or lens through which one looks at the world.”

What can climate practitioners do with Table 1? Climate action-logics could be helpful in understanding the dynamics of how climate concerns fall into the awareness-action gap. Research on action-logics in regards to climate helps explain why there are so many differing views on it, why the knowledge-deficit model fails, and also how and why people typically don’t see the problem in the same way as the climate communicators articulate it (Hedlund-de Witt 2012; Hochachka 2019; Lynam 2019). While segmentation studies on climate perceptions are commonplace in many nations and used by climate science and policy in their communications strategies or political campaigning (Maibach et al. 2011; Chryst et al. 2018; Hatch 2021; Leiserowitz et al. 2023), these tend to sort populations into typologies that reflect surface features in a given moment (Graham et al. 2014; Hine et al. 2014) rather than the perspective-taking mechanisms occurring at a deeper level to coordinate meaning (Hochachka 2019). When climate scientists and policy-makers (who are themselves coming from a specific set of action-logics) assume that scientific evidence and defensible policy proposals will win public support but overlook the meaning-making capacities of their audiences, they can fail to connect their message across diverse groups, resulting in insufficient support for such policies. Applying Table 1 as an extension of the existing segmentation tools already in practical use, could help climate practitioners to take stock of what people are aware of in a given population (i.e. their action-logics) and then to identify actions that make sense to them. An understanding of this spectrum of possible climate action-logics in diverse audiences could support policymakers to craft a broader array of possible climate actions, helping to close the gap between awareness and action.

Climate shadow

The above subsection discussed how people make meaning of climate change in their awareness. Here, I turn to examine the strategies employed—subconsciously—to keep climate change out of one’s awareness, what I introduce here as ‘climate shadow.’

Climate shadow refers to the ways that individuals and collectives edit their comprehension or push out that which is too difficult to manage into the shadow of their conscious awareness. Climate shadow explains the mechanism by which people repress or avoid ego-dystonic phenomena (i.e. aspects that are felt to be repugnant, distressing, unacceptable, or inconsistent with the rest of one’s sense of self) in their responses to the climate crisis. Norgaard (2006a, b), for example, in her study of climate change responses in Norway, found that “people want to protect themselves a little bit.” She describes how, in order to manage the internal conflict provoked by climate change, people may try to push it outside of their ‘norms of attention,’ which are the social rules of what is acceptable or appropriate to talk about. Sometimes people are not avoiding disconfirming evidence, as much as they are ignoring ‘inconvenient truths’ about climate change severity, through a similar psychological phenomena seen when smokers are exposed to anti-tobacco labels (Leventhal and Cleary 1980; Perga et al. 2023).

There is an important function of this psychological mechanism—that is, when someone is overloaded, it makes survival sense to selectively ignore certain things—and it is something that all people do, even those deeply committed and engaged in climate action. However, maintaining a difficult emotion in the shadow of one’s awareness takes a toll on people’s mental health. From psychology, it is known that once an emotion is placed outside of awareness, shadowed emotions can trigger reactions that are disproportionate to phenomena and events (Wilber 2000). It may also make people more vulnerable to manipulation through mis- or disinformation. Broader implications of how specifically climate shadow operates on the realization of climate action are important to consider.

Climate shadow may be a seldom-recognized reason why climate policies fail, as well as how climate denial manages to take root in certain population segments. While explanations of social inertia on climate action vary widely, action remains piecemeal and largely dominated by technical and economic explanations which miss the psychological and emotional dynamics occurring with this issue (Brulle and Norgaard 2019). Yet research on affective politics has found that emotions indeed shape how individuals interact with and approach the world around them; “emotional reactions influence (often outside of conscious awareness) a multitude of cognitive processes such as information processing, attitude formation, and political behavior” (Widmann 2021, p. 1). Avoiding climate change (often involuntarily or unconsciously), due to the strong, negative emotions that it can evoke, is a coping strategy; not wanting to feel such emotions can lead to negating, repressing, ‘numbing out,’ or denying awareness of climate change (Brulle and Norgaard 2019). Norgaard (2006a, b) recounts respondents in Norway explaining, “we don’t really want to know,” and in turn editing their comprehension of climate change based on this emotional response. This also occurs at a collective-level. Brulle and Norgaard (2019) describe how climate change can create a ‘cultural trauma,’—that is, a symbolic challenge to the status-quo social order, meanings, and ways of life—which is met with similar defense-mechanisms. Normative threats to the existing cultural system can instigate the emergence of anti-climate views; for example, “a desire to return to a safer, more comfortable era” contributes to climate opposition (Graves and Smith 2020, p. 6).

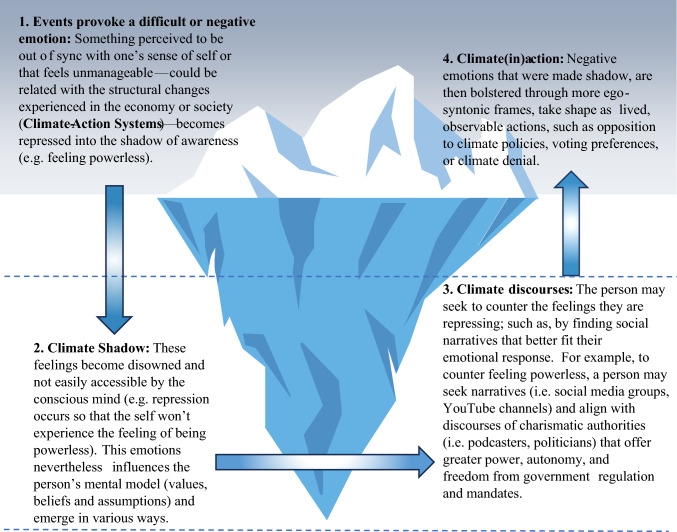

While the concept of climate shadow is being introduced in this paper and therefore work on it is preliminary, one way to theorize climate shadow in relation to the other elements is to use an adaptation of the Iceberg Model (Fig. 2). Originally cited to Goodman (2002) this model is now commonly applied in systems thinking to delve below the surface of events to see the deeper root causes. In Fig. 2, an example of how climate shadow operates from a repressed emotion through to assuming a social narrative that counters the negative feelings associated with that emotion, and then further into observable actions (pro- or anti-climate).

Fig. 2.

The Iceberg Model from systems theory applied to operationalize climate shadow (adapted from Goodman 2002). When emotions threaten one’s sense of self, culture, or identity (1), the self employs a psychological defense mechanism that represses those emotions out of conscious awareness to unseen layers of the metaphorical iceberg (2). This influences the middle layers in terms of what narratives, thought-leaders, media sources, and political leadership is sought (3), and the upper layers of the iceberg in terms of ones’ overt stance regarding climate action (4). How this may relate with climate action-logics is currently being studied

What can be done with the concept of climate shadow in practice? First, it can be used to make sense of existing research which has not been adequately incorporated into climate-action strategy yet is affecting its success. For example, in Canada, values of ‘respect for authority’ and ‘traditional family values’ plummeted from 1994 to 2018: “along with economic stagnation and the fall from middle-class membership, these threatening value declines may have left the segment of society which continued to place high emphasis on them feeling angry and fearful about their loss (hence the appeal of making things ‘great’ again or taking back control)” (Graves and Smith 2020, p. 9) The role of these emotions, alongside the structural realities of a diminishing middle-class prosperity and high-cost of living, have provoked backlash to climate policies in some parts of Canada. These scholars argue that this ‘ordered-populist’ segment is poorly understood and that the derisive response to it from progressives does little to address the core concerns that drive it (Graves 2019a, b). This is a problem, in their findings, since it has contributed to a heightened polarization in Canada and “there is no path to solving the critical challenges such as climate change in a world irreconcilably riven into two incommensurable views of the future.” (Graves and Smith 2020, p. 31). The tendency by populists to deny what is incontrovertible climate science is in large part driven not based on the strength of their arguments or evidence, as much as based on their feelings and emotions, and specifically by wanting to weigh in, have their opinions treated with respect, and their preferences honored (Nichols 2017; Goldstein 2023). In this type of case, the concept of ‘climate shadow’ could help to explain the affective aspects of climate opposition, engendering greater empathy and less derision, and thereby less polarization.

Secondly, the concept of climate shadow could inform both the design and process of public engagement. Inroads are being made into more affective or relational engagement, which has been found helpful especially with controversial, polarizing issues. For example, ‘deep canvassing,’ which involves the non-judgmental exchange of narratives in interpersonal conversations, has been found to durably reduce exclusionary attitudes in participants (Kalla and Broockman 2020) and ‘empathy mapping’ to better understand target audiences when crafting climate communications (Gibbons 2018). The concept of climate shadow could explain why such approaches to engagement are effective, namely as a way to surface and discuss difficult emotions and have concerns heard and accounted for. While emotions are subjective, they are in no way immaterial. For example, scholars submit that the emotional dynamics in populist segments in the USA in turn bolstered the Trump presidency in withdrawing the USA from the Paris Agreement (Goldstein 2023) and others posit that unchecked emotionally-fueled disinformation threatens even the foundations of democracy (McKay and Tenove 2021). Climate engagement that provides processes for citizens to air their emotions and feel that they have been accounted for in collective-action plans that involve them, may bode more successful (Nightingale 2015).

A third application of climate shadow is in dealing with mis/disinformation in a post-truth media context. Disinformation is defined by the Merriam-Webster Dictionary (2024) as “false information deliberately and often covertly spread (as by the planting of rumors) in order to influence public opinion or obscure the truth.” The emotional intensity of online media has been found to lead to motivated reasoning and the polarization of opinions, which McKay and Tenove (2021) refer to as techno-affective polarization. To better account for this emotional dimension of disinformation, scholars call for top-down interventions by government (i.e. introducing policies to curate or filter online participation), as well as mid-range (e.g. media companies and journalism organizations) and bottom-up (e.g. individuals and groups) interventions (McKay and Tenove 2021; Perga et al. 2023). Specifically the bottom-up interventions could be supported by accounting for the dynamics of climate shadow, getting to affective drivers and providing a more durable defense against disinformation campaigns.

Climate shadow helps to explain the social inertia that shrouds climate action and may assist in resolving the awareness-action gap. This body of research (Norgaard 2006a, 2011; Hamilton 2017; Brulle and Norgaard 2019; Rishi 2022) suggests that the issue is not that people are failing to act on their awareness of climate change; rather, people are trying to cultivate or maintain unawareness about the need for climate action, in order to withstand the strong emotions, suffering, and difficulties that are attached to it (i.e. fear of societal disruption, ontological insecurity, and so forth). How a consideration of climate shadow could be incorporated into climate communications and engagement, and what potential it holds for diffusing backlash and supporting a broader social mandate for climate action, is an exciting area for future empirical research.

Climate discourses

Climate change presents as a social, cultural and ideological crisis in need of collective sensemaking. People tend to make sense of the world through discourses and stories that have to do with their understanding about the world and events around them. For example, researchers contend that “populist…rhetoric [described above] has traction because of the emotion-inducing repertoires used to tell a story rather than through any measurable or objective ‘truth’ contained in it” (Homolar and Löfflmann 2021, p. 2 italics added). In this section, I consider this narrative dimension of the climate awareness-action gap.

Harries (2008, p. 482) summarizes this literature, defining a ‘discourse’ as: “an ensemble of ideas, concepts, categories and social representations through which meaning is given to physical and social realities.” Environmental and climate change discourses have been studied to explain the variance of social meanings about these subjects (Dryzek 2013; Leichenko and O’Brien 2019). Some universities have dedicated centres to study this interpersonal dimension of climate change, such as at Yale Centre for Climate Change Communication, and much research exists on how narratives matter regarding climate (O’Brien et al. 2007; Veland and Lynch 2016; Moezzi et al. 2017; Veland et al. 2018). Smith and Raven (2012) examine how narratives influence the public’s decisions about low-carbon development, noting that fit-and-conform narratives are more easily accepted by citizens than stretch-and-transform narratives that break with the status quo, even though it is the latter that will lead to long-term sustainability and equity.

Leichenko and O’Brien (2019) in their book, Climate and Society, draw on discourse theory and studies into the social construction of knowledge, to discern four climate change discourses—namely, the biophysical, critical, integrative, and dismissive—each that portray and understand the issue differently and prioritize different solutions (Table 2).3 Climate discourses help explain the difference in perceptions and sensemaking on climate. An example from Leichenko and O’Brien (2019) demonstrates how the perceived causality of the climate crisis differs across discourses. Whereas the biophysical discourse points to the ways that humanity has collectively contributed to climate change, a critical discourse submits that the causes of climate change are uneven, highlighting the power, vested interests, and roots of colonialism that have given rise to global warming. Meanwhile, an integrative discourse sees the validity of both positions yet views the cause of climate change to be linked to social and cultural norms, structural and systemic factors, and to individual and shared beliefs, values, worldviews and paradigms. A dismissive discourse is skeptical on the causative claims by other discourses, and rather suggests it could be a ploy or a hoax that serves entities with covert motives. In the book's second edition, to be published in mid-2024, the authors add a fifth climate change discourse—an eco-centric discourse—which sees climate change to be a result of a dualistic view of nature being separate from humans and society (O'Brien, 2024, personal communication). Often climate practitioners and policymakers rely predominantly on a biophysical climate discourse, however all four climate discourses are typically present in the general population; better understanding and aligning with those discourses would assist in securing public acceptance of a climate policy or fostering uptake of a climate action.

Table 2.

Climate change discourses (Leichenko and O’Brien 2019)

| Biophysical | Critical | Dismissive | Integrative |

|---|---|---|---|

| Climate change is an environmental problem caused by GHG emissions from human activities | Climate Change is a social problem caused by economic, political, and cultural processes that contribute to uneven, unsustainable patterns of development and energy use | Climate change is not a problem at all or at least note an urgent concern, and may even been a hoax | Climate change is an environmental and social problem that is rooted in particular beliefs and perceptions of human–environment relationships and humanity’s place in the world |

| Can be addressed through policies, technologies, and behavioural changes | Can be addressed through challenging economic systems and power structures that perpetuate fossil fuel consumption | Need not be addressed, and instead other issues should be prioritized | Can be addressed through challenging and changing mindsets, norms, rules, institutions, and policies that support unsustainable resource use and practices |

Climate discourses can help practitioners bridge the awareness-action gap by: (1) disclosing the range of interpretative frames on climate, (2) helping to discern what stories to tell and how; and (3) foregrounding narrative-based approaches in climate engagement. The ways climate change is portrayed in the media can reinforce the awareness-action gap, in part because it often predominantly proceeds from a biophysical climate discourse. The scientific papers on climate change that make news headlines showcase a narrow and limited facet of climate change knowledge (i.e., natural science and health), while research on technological, social, economic and energy-related aspects of climate change are underrepresented (Perga et al. 2023). This results in a biased focus in the media on the high risks and consequences of climate impacts, at the expense of other solutions and pathways. Elsewhere, the ‘doom, gloom, sacrifice’ climate story has been found ineffective in inspiring action (Stoknes 2014; Moser 2016). Yet De Meyer et al. (2020) report up to 98% of environmental news as negative, suggesting this is driven by a misguided sense that an increase in concern must precede action. These scholars draw on “evidence from psychology and neuroscience showing that ‘in real life actions drive beliefs’” and thereby argue a shift is needed from issue-based communication to action-based storytelling about climate (De Meyer et al. 2020, p. 2). Moser (2016, pp. 354–356) explain how certain climate messages (such as doom, loss, guilt, and identity-change) indeed make audience defensive and her work lists alternate communication approaches to use instead.

This interpersonal dimension of the climate challenge demonstrates the influence that intersubjectivity has on individuals. For example, people tend to take in information about climate change more positively from ‘trusted messengers’ than they do from politicians, media, or campaigners (Sawas et al. 2023). Yet, often the approach to climate action still tends to only superficially engage communities, which does not help to engender trust. The role and the power asymmetries of this interpersonal dimension, with respect to the climate stories that get made, shared, and promulgated, is crucially important to the success of bridging the climate awareness-action gap (i.e. Who is involved in climate storytelling? Who’s voices count, and how are they accounted for?) (Howarth et al. 2020). To ward off ongoing attempts to draw climate change into the ‘culture wars,’ Sawas et al. (2023, p. 8) reflect on how “bringing people in is the best way to mitigate their fears and help them to see themselves in the transition story.” Getting to such a shared climate story happens through active listening, drawing from a diversity of values, and acknowledging everyday concerns, and ensuring public consultations are sufficiently binding so that people can see their influence in decisions. Narrative-based public engagement on climate action occurring in various places worldwide is so far proving helpful in developing shared climate discourses (Marshall et al. 2017, 2018).

Climate-action systems

Structural-level factors regarding climate action refer to the ways that existing systems shape people’s ability to take action on climate change. Climate-action systems include technical systems, transportation and energy systems, heating and construction systems, socio-economic systems, communications systems, and so forth, that support or thwart pro-climate action (Sanne 2002; Geels et al. 2004; Shove 2010; Naito et al. 2022). Changing systems involves reckoning with policy lock-in and path dependency, which is not an easy task. Socio-technical regime theory describes how policies and political power can create a selection environment that works against incumbent innovations to the prevailing system, for example putting at a disadvantage path-breaking pro-climate innovations (Geels 2010). Systems dynamics factor heavily into the values-action gap, specifically in terms of power relations, structures, and dynamics that generate climate change in the first place and also conspire to constrain and influence people’s abilities to act on climate.

Climate-action systems are relevant in terms of understanding (1) the full weight of systems on individual choices as well as (2) in regards to power asymmetries and disproportionate impacts.

Municipalities tend to find that, despite many residents and businesses wanting climate action, “the systems they operate in often make it difficult to take those actions” (City of Vancouver 2020a, pp. 13–14). For example, even with a high degree of climate concern, a resident may face a socioeconomic situation that requires them to choose a cheaper option than the pro-climate alternative (Anguelovski et al. 2016, 2019), or, insufficient public transit options in a region means that, regardless of their stance regarding the climate, people remain caught in systems of high-carbon transportation (City of Vancouver 2015, 2020). These examples speak more to citizens being trapped in systems, rather than about their climate concerns per se. Yet the flipside of that scenario reveals the transformative potential of a systems-change approach; namely, if inclusive, pro-climate systems were accessible and competitive with high-carbon status-quo systems, they may become broadly used by citizens regardless of individuals’ climate concern.

However, for systems change to deliver on such potential, power asymmetries for climate action must be addressed. Some scholars argue that the key challenge in climate policy is in mitigating for how such policies create winners and losers and ignite distributive conflicts (Aklin and Mildenberger 2020). That is, climate policies that fail to sufficiently account for the most neglected citizens tend to provoke social unrest, detracting from net-zero goals (Tatham and Peters 2023). Efforts towards GHG emissions reductions must take stock of such asymmetric power relations which can become entrenched in societal systems and shape individuals’ agency. Anguelovski et al. (2019) describe the dual-threats that citizens can face: both the threat of climate inaction due to rising unpredictable weather events, as well as the threat of climate action itself, which can add additional costs to an already challenging socioeconomic situation. Both climate impacts as well as economic impacts of low-carbon transitions are disproportionate. Some segments of the population—such as low-income residents, indigenous peoples, and ethnic minorities as well as workers in resource-based industries and farmers— may suffer the brunt of climate impacts more heavily and will also experience the ramifications of net-zero transitions more significantly than those in more affluent socioeconomic sectors.

Against such a backdrop of winners and losers, support for climate action from these groups is not always certain. For example, Samí reindeer herders opposed a wind-power development in Fosen, Norway, seeing that they had more to lose in livelihood and culture than they stood to gain (Cambou 2020; Ravna 2022). Farmers in certain parts of the world have protested with concerns that the bill for the climate will be paid for by them, both in lower incomes but also a greater set of restrictions on their farming practices (van der Ploeg 2020). Key cities that proposed to reduce GHG emissions from cars with transport pricing failed to assemble public support, as it raised concerns about increased livelihood costs along with the loss of a perceived cultural way of life (Hochachka and Mérida 2023). Economic threats and changes in class structure are among the forces that set in motion the current polarization in Canada, which first served to provoke anti-mandate views during the pandemic, resulting in the “Freedom Convoy,” and more recently reformulated into an anti-climate sentiment (Graves and Smith 2020; Graves 2022). These examples support the assertion that this climate-action systems dimension, and how it in turn relates with climate action-logics, stories, and shadow, is keenly important in considering the climate awareness-action gap.

An example

Accounting for the intertwined aspects of this integral heuristic in climate engagement could help ameliorate the awareness-action gap. Box 1 illustrates this heuristic by examining the example of the ‘15-minute city’ urban-planning tool. The 15-min city concept, used in climate action planning, puts amenities close to where people live, thereby reducing the need to drive and increasing low-carbon mobility. I chose this case example as it’s reception in certain regions has many planners and progressive politicians perplexed: what should have been a feasible climate action for residents to get behind and to take up, has instead become a controversy. In Box 1, I examine the 15-min city using this heuristic, attempting to show how this simple planning tool became a hotbed of conflict, with take-aways for climate policy-design and engagement.

Box 1: Illustrative example of the climate awareness-action gap—The 15-min city planning tool for urban climate action

| Case: | What is the climate action, policy, or issue that you are focusing on? What is the current state of climate awareness in this context? | |

| The 15-minute city is an urban planning tool for developing self-sufficient neighbourhoods where most amenities are located in close proximity to where people live (Khavarian-Garmsir et al. 2023). This structurally creates low-carbon mobility by reducing the need for motorized travel, thereby reducing GHGs. The concept was promulgated by Carlos Moreno (2019), became popular coming out of the COVID pandemic when the resilience of cities was tested, and was taken up as a key strategy for post-COVID recovery (Allam et al. 2022) as well as incorporated into climate action planning. While it has been received positively for its environmental, social, and economic benefits by many (Khavarian-Garmsir et al. 2023), in the past few years, it has gotten mired in feuds over driving versus low-carbon mobility and has been construed as a conspiracy to restrict residents from leaving their neighbourhoods (Dawson 2023). This has occurred in various parts of Canada, such as Edmonton and Kamloops, for example. With its connection with pandemic-recovery, a negative association was forged between the 15-minute city concept and COVID lock-downs, producing the moniker ‘climate lock-downs.’ An additional tension arose regarding the overt intention for the 15-minute city to limit car travel, thereby putting at risk car-based culture, values, and identity. The ensuing backlash and opposition in some parts of Canada has been acute (Front Burner 2023). Key concerns by residents pertain to fear of restrictions on their freedoms to travel and overall threats to their loss of autonomy, loss of certain lifestyles (i.e. rural, suburban), and loss of their vehicles, at the hands of a government plan in which they had not been included in the design (Anderssen 2023). Some more extreme opposition viewed 15-min cities as “a ploy to control everything we do” as part of “a Surveillance State and social credit system” (Rothenburger 2023). Social media groups and charismatic authorities, such as Jordan Peterson, have played key roles in the misinformation on this topic (Dawson 2023; Regan 2023). It has had real impacts on the implementation of climate action; in Kamloops for example, its scheduled open-houses on climate had to be cancelled due to safety concerns, resulting in the district board’s inability to adopt the climate action plan last summer (Carrigg 2023). | ||

| Description: | Take-aways: | |

| Climate action-logics: | What are people aware of? What action-logic is informing the climate policy compared to the action-logics of publics? | • Rather than assuming everyone will get on side with a worldcentric frame (rational, achiever action-logic) for this planning initiative, instead climate actors could proceed with a more empathic politics. Seeking to understand the alternate views across a spectrum of meaning-making stages would have disclosed the range of perspectives, motivations, and concerns. |

| The 15-min city concept employs a worldcentric worldview (i.e.achiever and pluralist action-logics). It considers the interaction-effects between air quality on health, congestion and travel times, and as a structural intervention aligned with meeting climate targets (global and national). The action-logics demonstrated in the opposition to 15-min cities are sociocentric worldview (rule-oriented and conformist action-logics)— seeking to uphold existing lifestyles of the traditional Canadian culture, typified by heavy car usage — as well as a self-centric (opportunist action-logic), affirming personal rights and autonomy, distrustful, and viewing rules as loss of freedom. Much of the controversy and opposition occurred due to this misalignment between climate action-logics of planners versus certain groups in the population. The misalignment was also exemplified by how proponents of the 15-min cities had inadequately accounted for the meaning that citizens held about the pandemic lock-downs. In construing 15-min cities as a low-carbon initiative in a post-pandemic recovery, the concept linked the least popular aspect of the pandemic (mandated lock-downs) with climate action. In so doing, climate was able to be dragged into an already-heated debate about the pandemic regulations. | • The 15-min city could be framed in a manner that is more aligned with where people are coming from; more connected with the socio- and self-centric action-logics in audiences. | |

| • Relating with the socio-centric interest in social stability and traditional lifestyles, the 15-Min City could have been presented as a way to get back to the original Canadian community-living (e.g. notably Edmonton began using such frames as such, creating a ‘community of communities,’ or, ‘small towns in our big city’ (Dawson 2023)) | ||

| • Relating with key motivators for self-centric action-logics, namely autonomy and freedom, planners could better consider how the 15-min city concept can be operationalized to empower citizens, perhaps through ways in which public engagement findings can result in changes to urban planning strategies thereby demonstrating to local people that their perspectives count | ||

| Description: | Take-aways: | |

| Climate shadow: | In what ways are people trying to keep climate change out of their awareness, and why? | • From psychology, it is known that once an emotion is placed outside of awareness, shadowed emotions can trigger reactions that are disproportionate to phenomena and events (Wilber 2000). What appeared to city councilors as an innoxious planning tool—a tool that had been around for a long time already without giving rise to controversial reactions—suddenly provoked disproportionate backlash. This is partially explained by the mechanism of climate shadow. |

| Climate shadow factors into this issue in at least two ways. First, restricting car-based travel by changing the built environment of a region represents the kind of societal disruption that some people fear in regards to climate response. Car-dependent lifestyles and cultures are deeply rooted in Canada, based on values of independence and freedom, as well as other frames (Sovacool and Axsen 2018). In Vancouver, respondents in a 2022 study on urban climate action explained “cars are [not just] how people get around, [the car is] an extension of themselves” (Hochachka et al. 2022, p. 1028). The association between curbing car use and the 15-min city inadvertently activated strong emotions, such as loss, fear, and a sense of being powered-over. Second, coming out the pandemic, where people were socially isolated and restricted in their movements, some citizens feared this planning tool to be a covert means to replicate the lock-downs. City planners did not specify otherwise. Anderssen (2023) reports how senior city planner Sean Bohlein in Edmonton said that the plan had not specifically stated that the 15-min city would not include lock-downs, saying: “We didn’t consider that. There are infinite things the plan will not do. We’re not going to neuter your chinchilla, for example.” This statement overlooked and also dismissed the emotional toll of the pandemic on people, and didn’t account for the fear people felt regarding being restricted in their movements. | • Communications about the 15-min city as an urban planning tool cannot only be technical, and needs to also recognize the role that emotions play in the reception by publics. The emotions in question here relate with the loss of a cultural identity regarding the car—the freedom it symbolizes, and the perceived right to a car-based lifestyle—as well as a loss of autonomy over one’s ability to choose and create the life one wants. | |

| • The design process needs to account for those emotions in one way or another. Design for the 15-min city would benefit from a genuine citizens’ assembly process where people participate in that which has real consequences on their lives. It cannot be an academic concept laid onto people’s daily realities, but rather needs to be brought into dialogue with people to make sense of it in the context of their daily realities. In providing a more genuine and co-generated engagement process, citizens would have opportunities to air their emotions about the initiative, and have their concerns addressed and reflected in climate plans. | ||

| Climate discourses: | What are the narratives that people hold to make sense of this situation, and how are these stories being disseminated? | • Instead of assuming one’s own climate discourse is shared by others, policymakers need to realize that the biophysical climate discourse is but one of at least four discourses; and thus to employ more diverse messaging that can attend for and include other sensemaking on climate |

| The role of climate discourses in this case is relevant in understanding: (1) which climate discourses are at play, (2) where the oppositional narrative originated, (3) how this narrative was perpetuated on social media, and (4) how it might be resolved through deep engagement with the public. The 15-min tool as a climate action strategy proceeds from a biophysical climate discourse, whereas the oppositional response came from a dismissive climate discourse that did not see the problem in the same way as policymakers. It is uncertain whether the origins of the opposition were anti-climate to begin with, or whether climate was dragged into the post-COVID ‘culture-war.’ But, what is clear is that “much of the pushback against the 15-min city concept is rooted in fiction rather than fact” (Baker and Weedon 2023). The narratives that provoked pushback were characterized by the post-pandemic frustration regarding mandates constraining behaviours and fears and fatigue of citizens feeling heavily regulated in a manner that is unusual for a Western liberal democracy. The anti-15-min city response took root in this narrative-context. It was further galvanized in certain echo chambers on social media, where previous rational-legal authorities have been replaced for charismatic authorities (such as podcasters like Jordan B. Peterson) (Regan 2023). The amplification of misinformation about the 15-min cities in such groups spread quickly. When Edmonton City Councillor Andrew Knack met with concerned residents about the 15-min city planning tool, and sought to hear their concerns and address misperceptions or misunderstandings about the planning strategy, he was reported in saying “Talking it through at least makes a person feel that somebody listened to them” (Anderssen 2023). | • Better listening by policymakers to the concerns of residents may have headed off much of what then became a more dramatic narrative. The extent to which city councilors expressed shock in the anti-15-min city response is a testament to how disconnected they were from the prevalent concerns of citizens coming out of the pandemic. Requests for the municipality to guarantee freedom of travel and to state that it “won’t restrict access to medical care, bank accounts, sporting activities, utilities, churches, groceries or the ability to garden” (Rothenburger 2023), were held against a pandemic backdrop in which the government had restricted some of those freedoms (i.e., via the lock-downs, vaccine mandates, and when the Canadian prime minister invoked the Emergencies Act to be able to restrict bank accounts of those who supported the “Freedom Convoy” in Ottawa). | |

| • More focus and resources could be placed on the social-emotional design, such as through climate dialogues and narrative workshops. Deep canvassing could be helpful now that the issue is controversial (Kalla and Broockman 2020). This provides people a way to feel heard and included, and could support them in gaining ownership over the subsequent plan rather than having the sense it was mandated. | ||

| Description: | Take-aways | |

| Climate-action systems: | What systemic constraints are people experiencing which could support or thwart the acceptance of the 15-Min City Plan? | • Attention to climate-action systems reveal how the socioeconomic constraints people experience can thwart the acceptance of climate policies and acknowledge the power asymmetries present in climate challenge |

| The consideration of climate-action systems reveals the structural constraints that people experience which may be contributing to the opposition. This raises the justice and equity dimension of this planning tool, as well as attends to the power asymmetries baked into policy and planning processes. Applying a structural analysis and a climate justice and equity lens to guide policy-design would consider whether 15-min city lifestyles are within reach socioeconomically and to ensure that negative impacts are not borne disproportionately to those who can least afford to manage them. People may seek to drive for groceries for economic reasons (e.g. where protests arose in Canada, local boutique-stores are often more expensive than big-box stores like Walmart, Canadian Superstore or Costco Wholesale, located outside the urban core). It will be important to analyze whether 15-min city amenities offer cost-comparative alternatives at the neighbourhood scale to ensure that a pro-climate land-use plan does not make life substantially more expensive for residents. | • When replacing long-standing systems that people rely on, it is necessary to involve people in weighing trade-offs and in the decision-making around those changes. Citizens need to be included and accounted for in the climate-action systems being created, especially if it means adding to their cost of living and/or forcing alternative systems on them by way of ‘choice-editing.’ | |

| • Engaging more participatory methods, in which the plan can be interrogated by the people whose lives it will impact, trade-offs and risks can be weighed, and through which the plan can incorporate diverse perspectives of residents. Often such perspectives shed insight from within the lived realities of citizens and draw on local knowledges in ways that typically are missed by employing a techno-managerial approach alone | ||

| Summary | |

|---|---|

| Climate action-logics and Climate shadow | Climate action |

|

• Publics meaning-making about the problem (self-centric, affective and socio-centric, traditional) differed from the planners and municipal staff (rational, worldcentric action-logic) • Fears of being powered over, identity-loss, and isolation from the pandemic extended into climate. |

• A simple innoxious planning tool • Supports low-carbon behaviour change by putting amenities close to residences • Lessens the need to drive; increases low-carbon mobility |

| Climate discourses | Climate-action systems |

|

• Biophysical climate discourse (focused on techno-managerial change) met a dismissive climate discourse (focused on a different perceived problem around liberty and autonomy) • Hooked into narratives re taking-back control, ‘making great again’, and distrust in govt from pandemic • Climate pulled into that pre-existing tension • Echo chambers, algorithms, podcasters played key roles in shaping these narratives |

• Concerns that restructuring the city could also make driving for groceries more difficult, which is where some residents prefer to shop for socio-economic reasons (local boutiques are typically more expensive than Costco or Superstore) • Disproportionate impacts in an already difficult economy for many people, with high-costs of living • Power asymmetries in who makes decisions and who bears the consequences |

Recommendations for application

An integrative ‘turn’ in climate engagement is needed, specifically for better understanding and reconciling the awareness-action gap. Policymakers and climate advocates need to understand that techno-fixes are not enough and also that not everyone experiences and values climate action the same way. This integral heuristic discloses the multifaceted dilemma that is formed by these psychosocial and structural aspects and weigh on people’s sense-making and action. Table 3 includes further applications for how policymakers and climate communicators might put this heuristic into practice—including some known and also some new strategies—which may help to lessen the gap between climate awareness and action.

Table 3.

Applications of this heuristic for climate communications and engagement

| Align communications | Consider how communications can best take stock of the tensions that individuals and groups wrestle with when it comes to climate, including skillful alignment of climate action-logics and climate discourses between policy-makers and audiences. This could include drafting communications to avoid triggers and support more resonant meaning-making frames, and connecting with citizen’s ‘objects of care’ that motivates people in connecting climate concern with action, be that changed behaviours, lifestyles, or voting preferences (Wang et al. 2018) |

| Seek to understand | Balance the current reliance on technical, quantitative research with qualitative research from social science, such as semi-structured interviews, action-research methods, and focus group sessions to gain ‘thick descriptions’ of the multiple tensions that people manage, and the way they make meaning about climate change. This is not to sell the intended policy better (i.e. social marketing), but rather to design the policy from the bottom-up in consideration of these tensions and subjectivities, and in better alignment with the climate action-logics of audiences (Nightingale 2015; Hochachka 2019) |

| Convene and listen | Facilitating narrative workshops or other dialogue processes can be part of climate action programming as a way to practice empathetic engagement, build shared climate stories, and facilitate dilemma resolution (Shaw and Corner 2017) |

| Identify and integrate emotions | Employ affective tools to design climate policy in ways that account for residents’ climate emotions. This could include workshops on ‘climate shadow’ or other types of facilitated processes in which participants surface and discuss emotions regarding climate that are difficult to manage. Design policies and engagement to foster positive emotions and group contributions, rather than emotions of sacrifice and loss (Harth 2021) |

| Practice empathy and inclusion | Conduct empathy mapping of audiences to better grasp the lived consequences of a climate-action strategy and to more fully perceive the emotional and structural aspects that individuals face when it comes to climate action (Gibbons 2018) |

| Consider agency and structure explicitly in policy-design processes | Address the agency-structure tension that climate change activates. Regarding agency, create psychology-informed policy commissions to assist in the design of climate policy which may lessen the dilemmas that residents will face as a result of these measures and empower their agency to act. Regarding structure, directly address the power asymmetries that can stoke climate opposition through deep engagement processes with publics. Citizen involvement ought to transpire in binding results to some degree, such that they can see their participation has been accounted for, and also that the climate-action system in question has been molded by their own perspectives as well, not simply put on them from the state (Sawas et al. 2023) |

Conclusion

In this article, I have brought together four interacting aspects that are relevant for climate awareness to move into action. This integral heuristic included the ways that people become aware of climate change, through their perspective-taking and organization of meaning, as well as how they can seek to stay unaware about climate change, through the activation of a certain psychological defense mechanism that helps the self-system manage difficult emotions (referred to as shadow). This inquiry also touched on how people are enmeshed in social contexts (i.e. sub-cultures, echo-chambers) that construe climate via stories and discourses that nudge them to or away from climate action; and are locked into systems that shape and constrain their actions in terms of where and how they are able to advance pro-climate choices. Overall, greater appreciation is needed for the ways that these aspects shape the dilemmas people face regarding climate change. This isn't just aimed at having an easier time getting people to change their behavior or better convincing them about pro-climate lifestyles. Rather, it aims to connect with what people care about and how they make sense of the climate challenge in their daily lives, while also overcoming disproportionate impacts and unfair structural constraints. It may also help to unravel the attempts to drag climate into the ‘culture wars,’ by working at a deeper layer of the challenge than typical techno-fixes are able to reach. Such an integral heuristic applied to climate action strategies may help to bridge the gap between awareness and action, moving the untapped yet significant potential of pro-climate behaviour and lifestyle changes to lower GHG emissions towards reality.

Acknowledgements

The author acknowledges Prof. Karen O’Brien, Prof. Ioan Fazey, Dr. Irmelin Gram-Hanssen, Joanna Kerr, and James Boothroyd for their help in reviewing and editing the article, to supervisor Prof. Robert Kozak for his academic guidance, and to the Mitacs Elevate fellowship research Grant IT26581 and the MakeWay Foundation for financial support.

Gail Hochachka

is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada. Her research interests include the human dimensions of climate action and transformations to sustainability, with a specific focus on the action-logics and worldviews shaping climate perceptions and discourses.

Footnotes

An exception is the University College London’s Climate Action Unit, which draws on psychology, sociology, and an understanding of energy transitions, and is set up precisely to support the public sector in policy development.

I will use action logic and meaning-making stage interchangeably in this article. Besides an understanding of these different action-logics—which is based within an academic discipline of psychology that typically employs an ontology of separation between subject and object, humans and nature—other ways of knowing, such as indigenous cosmologies, can employ a relational ontology, which is reciprocal, co-constitutive, and enactive, and are found to perceive climate change in unique ways (Huffaker 2021).

In a forthcoming edition of this book, they include a fifth, an eco-centric discourse. The second edition, to be published in mid-2024, adds an eco-centric discourse which sees climate change to be a result of a dualistic view of nature being separate from humans, and that the response ought to repair that division through collaboration, coexistence, and responsibility (O'Brien, 2024, personal communication).

Publisher's Note