Abstract

Background

Gut microbiome modulation to boost antitumor immune responses is under investigation.

Methods

ROMA-2 evaluated the microbial ecosystem therapeutic (MET)-4 oral consortia, a mixture of cultured human stool-derived immune-responsiveness associated bacteria, given with chemoradiation (CRT) in HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer patients. Co-primary endpoints were safety and changes in stool cumulative MET-4 taxa relative abundance (RA) by 16SRNA sequencing. Stools and plasma were collected pre/post-MET-4 intervention for microbiome and metabolome analysis.

Results

Twenty-nine patients received ≥1 dose of MET-4 and were evaluable for safety: drug-related adverse events (AEs) occurred in 13/29 patients: all grade 1–2 except one grade 3 (diarrhea). MET-4 was discontinued early in 7/29 patients due to CRT-induced toxicity, and in 1/29 due to MET-4 AEs. Twenty patients were evaluable for ecological endpoints: there was no increase in stool MET-4 RA post-intervention but trended to increase in stage III patients (p = 0.06). MET-4 RA was higher in stage III vs I-II patients at week 4 (p = 0.03) and 2-month follow-up (p = 0.01), which correlated with changes in plasma and stool targeted metabolomics.

Conclusions

ROMA-2 did not meet its primary ecologic endpoint, as no engraftment was observed in the overall cohort. Exploratory findings of engraftment in stage III patients warrants further investigation of microbiome interventions in this subgroup.

Subject terms: Drug development, Head and neck cancer

Introduction

Accumulating evidence has linked the gut microbiome composition and function with increase antitumor immune responses and improved efficacy of immune-checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) [1, 2]. As such, therapeutic manipulation of the gut microbiome in cancer patients is currently an area of active investigation. Fecal microbiome transplantation (FMT) via colonoscopy, using stools from ICI responders has shown encouraging results, but the logistical difficulties of this approach and the risk of toxicity, including fatal bloodstream infections from donor-derived antibiotic-resistant organisms, have limited its development [3–5]. Oral alternatives to FMT including dietary modifications, use of probiotics and orally-administered bacterial consortia are now being evaluated in clinical trials, either alone or in combination with other immunotherapies in patients with primary or secondary resistance to ICI [6]. Microbial consortia effectively prevent recurrence in patients with Clostridiodes difficile colitis, and are also being developed for inflammatory bowel disease [7, 8]. Microbial Ecosystem Therapeutics (MET)-4 is an orally delivered microbial consortia containing 30 stool-derived bacteria associated with ICI response and/or capable of inducing interferon-mediated CD8 + T-cell responses [1, 2], designed to enhance anti-tumor immune responses in the context of ICI. The safety and tolerability of MET-4 given in combination with ICI in advanced cancer patients has been recently evaluated in a first-in-class phase 1 study (MET4-IO) conducted by our group, showing the compound is safe, with MET-4 taxa engraftment being observed in several patients [9].

The role of the gut microbiome has remained mostly unexplored in head and neck cancer, as most of the efforts have been focused on studying the relationship of oral microbiome as a biomarker for tumorigenesis and immunotherapy efficacy [10, 11]. We had previously investigated both oral and gut microbiome composition before and after chemoradiotherapy in patients with Human Papillomavirus (HPV)-related locally-advanced oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (LA-OPSCC) and reported variability in ICI-responsiveness associated taxa across stages in this patient population [12, 13]. These preliminary observations suggested an opportunity for the evaluation of immunotherapies with modulation of the intestinal microbiome in this patient population. As the combination of ICI and (chemo)radiotherapy in either neoadjuvant, concurrent or adjuvant settings is actively being evaluated in prospective clinical trials involving HPV-related LA-OPSCC, the potential role of the intestinal microbiome modulation as a therapeutic tool in this setting warrants a comprehensive exploration [14] (NCT03765918, NCT03452137, NCT03952585). The investigator-initiated ROMA-2 trial, is the first interventional study evaluating the safety, feasibility and ecological effects of MET-4, in combination with definitive chemoradiotherapy in HPV-related LA-OPSCC.

Methods

Study population and trial design

ROMA-2 (NCT03838601) is a single-center, investigator-initiated feasibility study designed to assess the safety, tolerability and engraftment of MET-4 bacterial taxa when given in combination with chemoradiotherapy. Eligible patients had previously untreated pathologically-confirmed squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx, HPV-related, with no evidence of metastasis (M0) as per American Joint Committee on Cancer eighth edition and deemed candidates for definitive concurrent chemoradiation (CRT) with single agent cisplatin as per standard of care and according to Princess Margaret Cancer Center institutional protocols. Subjects unable to swallow orally administered medications or any subjects with gastrointestinal disorders likely to interfere with absorption (e.g. bowel obstruction, short gut syndrome, blind loop syndrome, ileostomy, etc.) were excluded. HPV status was determined by p16 staining and classified as positive if there is nuclear and cytoplasmic staining in ≥70% tumor cells. In situ hybridisation to confirm the presence of high-risk HPV DNA was performed in equivocal cases.

All patients were to receive MET-4 daily from week 1 to week 4 of CRT or unacceptable toxicity whichever occurred earlier. Tumor swabs, stools and blood samples were collected during the screening period (baseline), at week 4 following completion of MET-4 (window: +7 days from week 4 day 1), at the end of CRT (window: +3 weeks after last day of radiotherapy), and at the 2-month follow-up visit scheduled as per institutional standard practice (window: + 4 weeks from scheduled visit) (Fig. S1).

The primary objectives of the study were safety and toxicity profile of MET-4 when administered concurrent to CRT using the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events V.5.0; and the relative abundance of MET-4 associated bacterial strains in stool samples collected at week 4, end of CRT and 2-month follow-up timepoints. Secondary objectives included the evaluation of changes occurring in the bacterial taxa diversity of tumor swabs and stool samples between baseline and the consecutive timepoints; and the comparison of the changes occurring in both oral and intestinal microbiome composition and diversity with MET-4 intervention versus CRT alone. For the latter goal, the microbiome data from the observational ROMA LA-OPSCC-001 (ROMA-1) study was used [12]. Exploratory objectives included the correlation of stool and serum metabolomic profiles before and after MET-4 intervention. All patients enrolled that received at least one dose of MET-4 were evaluable for safety. According to protocol, patients were considered evaluable for co-primary ecological endpoints if they received at least 75% of planned MET-4 dosing; did not receive antibiotic therapy at any time between baseline and completion of MET-4; and paired samples at baseline and week 4 timepoint were successfully collected.

Treatment and follow-up

MET-4 (0.5 g capsule) was administered orally as an initial daily loading dose of 20 capsules (2–10 × 1010 colony forming units) over 2 days (starting day 1 of radiotherapy followed by a daily maintenance dose of 3 capsules (6–30 × 109 colony forming units)) of MET-4 until week 4 of CRT. All patients received intensity-modulated radiotherapy to a gross tumor dose of 70 Gy in 35 fractions over 7 weeks (2 Gy/fraction). Concurrent cisplatin (three-weekly at 100 mg/m2 on radiotherapy days 1, 22 and 43 or weekly at 40 mg/m2 for 7 weeks) was delivered according to institutional standards. The choice of a three-weekly versus weekly schedule was based on patient’s Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance scale and comorbidities as assessed by medical oncologist. All patients had a prophylactic gastrostomy tube placed within 3–4 weeks from the start of radiation as per institutional standard practice. Follow-up after treatment completion was conducted according to institutional protocol. Local and regional recurrences were confirmed histologically, while distant metastases were diagnosed by unequivocal clinical/radiologic evidence ± histologic confirmation.

Study oversight

The study protocol (supplementary material) and all the related amendments were approved by the Institutional Review Ethic Board. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and with Good Clinical Practice as defined by the International Conference on Harmonization. Before enrollment, all patients provided written informed consent. Established bi-weekly safety calls occurred to provide oversight of safety. Data collection and monitoring were performed throughout the study and after enrollment was completed. Monitoring of study conduct, including all adverse events, was performed by the Princess Margaret Cancer Center Tumor Immunotherapy Program once every two weeks and by the Data Safety Monitoring Committee twice a year and as needed.

Microbiome analysis

DNA was extracted from the patients’ frozen fecal material using the Quick-DNA Fecal/Soil Microbe Kits (Zymo Research; Irvine, CA, USA) and normalised by stool weight. Library generation and next generation sequencing were done at Mr DNA Molecular Research (Shallowater, TX, USA). The 16 S rRNA gene V4 variable region was amplified with PCR using primers 515 F (GTGYCAGCMGCCGCGGTTA) and 806 R (GGACTACNVGGGTWTCTAAT), with the barcode on the forward primer, and HotStarTaq Plus Master Mix Kit (Qiagen; Germantown, MD, USA). PCR consisted of 30 cycles of 94 °C for 3 min, then 30–35 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 53 °C for 40 s, and 72 °C for 60 s, and a final elongation step at 72 °C for 5 min. After amplification, PCR products were resolved by electrophoresis on a 2% agarose gel to determine amplification and relative band intensity. Multiple samples were pooled in equal proportions, on the basis of their molecular weight and DNA concentrations and purified with calibrated Ampure XP beads (Beckman Coulter; Brea, CA, USA). Pooled and purified PCR product was used to prepare an Illumina (San Diego, CA, USA) Nextera DNA library. Sequencing was done by Mr DNA (Shallowater, TX, USA) using an Illumina (San Diego, CA, USA) MiSeq with version 3 reagents and generating 300-bp paired-end reads. Reads in which more than 70% of bases had a Phred score of 30 or more were retained and trimmed using DADA2 [v1.14.1] [15]. Taxonomy was assigned with a native implementation of the naive Bayesian classifier method and trained with the Silva database [v.132]. Amplicon sequence variants were assigned and collated to the closest related taxon using NCBI BLAST.

Targeted metabolomics

Plasma and stool samples were sent to The Metabolomics Innovation Center (TMIC)(Edmonton, AB) for targeted metabolomic profiling using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). Samples were profiled for panels of bile acids and short chain fatty acids [9]. Analytes were included in statistical analyses if they were detectable in at least 40% of samples.

Statistical analysis

This is a signal-finding study without any pre-specified statistical assumptions. Descriptive statistics were used to summarise MET-4-related adverse events, as well as patient and disease characteristics. Ecological outcomes (MET-4 cumulative relative abundance, change from baseline, absolute count of MET-4 taxa >1%, Shannon diversity and observed operational taxonomic units (OTUs)) were provided for all MET-4 recipients and compared across timepoints as continuous variables with non-parametric ANOVA and paired T-tests. For alpha-diversity metrics, samples were rarefied to a sequencing depth of 42141 reads (the lowest depth for a sample included in the analysis). Fold-change in MET-4 relative abundance between baseline samples (pre-MET-4) and post-MET-4 timepoints were generated by dividing post-treatment relative abundance by the baseline relative abundance and log transforming the resulting fold-change, then using one-sample T-tests to compare the distribution of these values to a ‘no-change’ reference value of 0. Forest plots with differential relative abundance taxa between timepoints and across stage subgroups were generated by Maaslin2 with study participant included as a random effect. Compositional differences in Bray-Curtis dissimilarity (beta diversity measure) were plotted on PCoA plots and compared by permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA).

Concentrations of metabolites were compared across sampling timepoints for MET-4 treated using ANOVA with log10 transformation when appropriate. Log 2-fold change (L2FC) in metabolite concentration was calculated by dividing post-MET-4 metabolite concentrations by baseline metabolite concentration and log2 transforming the data. All analyses were performed in Graphpad Prism, QIIME2.2 2022.8 [16] and R Studio 2022.07.1

Results

Study patient population

Between 18/July/19 and 07/July/21, a total of 30 patients with LA-OPSCC candidates for c CRT were enrolled in the study. Total population and evaluable subjects for MET-4-related analysis are summarized in Fig. S2. Cohort characteristics are shown in Table S1. Median age at diagnosis was 61 years old (45–73). Most patients were male and 60% were former smokers with a smoking history over >10 pack-years, with 13% being current smokers. Over 95% of the tumors were located in the base of tongue (53%) and tonsil (43%). Half of the study patient population presented with stage III disease. All patients completed the radiotherapy course, and almost 80% received ≥200 mg/m2 cisplatin cumulative dose. Up to 20% of patients received antibiotics 1-month prior to or during CRT, with only 1 patient receiving them during the course of MET-4 treatment. At the time of data cut-off (Aug 1st, 2022), with a median follow-up of 20 months (8–35), all patients were alive: 25 with no disease recurrence, and 2 with disease recurrence (1 locoregional and 1 distant, both with stage III at presentation).

MET-4 was safe and tolerable in the context of concurrent chemoradiotherapy

A total of 29 patients took at least one dose of MET-4 and were evaluable for safety (Fig. S2). Treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) attributable to MET-4 occurred in 13/29 patients (45%) (Table 1). No grade ≥4 events occurred. One patient had grade 3 diarrhea lasting one day, resolved with loperamide, and was able to continue and complete MET-4 planned dosing. Grade 1 and 2 TRAEs included bloating (N = 2), nausea/vomiting (N = 3), diarrhea (N = 4), flatulence (N = 2) and belching (N = 2). Completion of preplanned MET-4 dosing over 75% was achieved by 21 patients (72%). Reasons for MET-4 early discontinuation were CRT-induced toxicity (nausea and vomiting and difficulty swallowing due to mucositis) (N = 6), MET-4 TRAEs (N = 1; G3 diarrhea) and withdrawal of consent (N = 1). Three patients of this cohort developed long-term grade 3-4 toxicity related to CRT: osteoradionecrosis (N = 2: R2-003 and R2-008) and persistent ulceration of the base of tongue (N = 1; patient R2-025).

Table 1.

Treatment-related adverse events attributable to MET-4.

| All Grades | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nausea/Vomiting | 3 (10%) | 3 (10%) | 0 | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 4 (14%) | 1 (3%) | 2 (7%) | 1 (3%) |

| Bloating | 2 (7%) | 2 (7%) | 0 | 0 |

| Flatulence | 2 (7%) | 2 (7%) | 0 | 0 |

| Belching | 2 (7%) | 2 (7%) | 0 | 0 |

MET-4 taxa were not augmented following MET-4 intervention

A total of 313 out of the 360 planned samples were collected across timepoints (87% compliance): 105/120 stools, 103/120 tumor swabs and 105/120 plasma samples (Table S2). Twenty patients (69%) were deemed evaluable for the ecological endpoints based on pre-specified criteria (Section 2.1). Within this group, tumor swab and stool samples at the post CRT timepoint were not available for one patient.

The primary ecological outcome is shown in Fig. 1. No significant changes in the cumulative relative abundance or absolute count of MET-4 taxa over 1% in stools were observed at week 4 and consecutive timepoints when compared to baseline (Fig. 1a, b). For all patients, the mean (± standard deviation) cumulative relative abundance of MET-4 taxa at baseline, week 4, post-CRT and at 2-month follow-up were 0.26 (±0.09), 0.28 (±0.09), 0.25 (±0.11) and 0.28 (±0.11) (p = 0.82). Changes in cumulative relative abundance MET-4 taxa from baseline to week 4 were not significantly driven by specific MET-4 taxon (Fig. 1c). Gemmiger formicilis was significantly associated with increased MET-4 cumulative relative abundance after CRT, and Clostridium leptum, Bacteroides eggerthii, Parabacteroides distasonis and lactocaseibacillus casei/paracasei/zeae were significantly associated with increased MET-4 cumulative relative abundance at the 2-month follow-up timepoints (p < 0.05). We observed an increase in MET-4. cumulative relative abundance in at least one timepoint post-MET-4 intervention in 15/20 patients (Fig. S3). Changes in MET-4 cumulative relative abundance varied significantly by patient and by taxon (Figs. S4, S5).

Fig. 1. Ecological primary endpoints.

Stool samples were collected pre-MET-4 intervention at baseline (BL) and post-MET-4 intervention at week 4 (W4), post-CRT (POST) and at 2-month follow-up (FU). 16 S rRNA gene sequencing was used to determine: (a) Cumulative relative abundance (RA) of MET-4 taxa; and (b)—number of MET-4 taxa with a relative abundance of at least 0.01 (1%) of the stool microbiome at each timepoint; (c)- A volcano plot depicting differentially abundant MET-4 taxa at post-intervention timepoints. X axis shows the delta cumulative relative abundance MET-4 taxa from baseline to week 4 by the fold-change of individual MET-4 taxon RA at each timepoint. Gemmiger formicilis and Clostridium leptum, Bacteroides eggerthii, Parabacteroides distasonis and lactocaseibacillus casei/paracasei/zeae are the only taxa significantly associated with increase MET-4 cumulative relative abundance at post-CRT and FU timepoints, respectively (p < 0.05). Q-values are shown for taxa with p < 0.05.

Patients with stage III disease had greater MET-4-associated ecological responses

Exploratory subgroup analysis according to stage showed significant changes in MET-4 taxa cumulative relative abundance in stage III vs stage I-II patients (p = 0.008) (Fig. 2a): mean (± standard deviation) was significantly higher at both week 4 and 2-month follow-up timepoints (0.34 ± 0.06 vs 0.22 ± 0.08, p = 0.03; and 0.33 ± 0.06 vs 0.22 ± 12, p = 0.01, respectively) but not at baseline or post-CRT (p value > 0.99). Paired analysis showed a trend towards increased cumulative relative abundance of MET-4 taxa at week 4 vs baseline in the stage III subgroup (p = 0.06) with no differences at other timepoints (Fig. 2b). There were no changes observed for any timepoint in the stage I-II subgroup. No significant differences in Shannon diversity index were observed across timepoints by stage subgroup although a decrease in diversity could be observed at week 4 in the stage III subgroup (Fig. 2c). Overall stool community composition by Bray-Curtis dissimilarity did not significantly differ by stage subgroups (Fig. 2d). No differentially abundant gut taxa were observed by stage subgroups when using subject as random effect.

Fig. 2. Exploratory stage subgroup analysis.

a Cumulative relative abundance of MET-4 taxa at each timepoint by stage subgroups. b Paired-analysis of MET-4 taxa cumulative relative abundance at each timepoint post-MET-4 intervention compared to baseline. c Alpha-diversity measured with Shannon diversity index at each timepoint by stage subgroups. d Bray-Curtis Principal Coordinates Analyses (PCoA) showing stool community composition by stage at each timepoint. Each cercle represent a sample and the color represents the stage subgroup. e Paired-analysis of MET-4 taxa cumulative relative abundance post-CRT vs baseline in stool samples from ROMA-1 study. f Cumulative relative abundance of MET-4 taxa in stools pre- and post-CRT by stage subgroups. G- Cumulative relative abundance of MET-4 taxa in stools pre- and post-CRT in ROMA-2 vs ROMA-1 studies. P values are only shown when significant (p < 0.05).

MET-4 associated taxa tend to decrease following CRT in patients with stage III disease

We compared the changes occurring after MET-4 intervention versus CRT alone using the observational prospective cohort from the ROMA-1 study [12]. The 16SRNA sequencing data obtained from stool samples collected at baseline and post-CRT in the ROMA-1 were pipelined together with 16SRNA sequencing data from ROMA-2 samples in order to allow the comparison of the relative abundances of species included in MET-4 in both cohort sets. For all patients in ROMA-1, the mean (± standard deviation) cumulative relative abundance of the taxa included in MET-4 at baseline vs post-CRT were 0.27 (±0.08) and 0.24 (±0.12), respectively (p = 0.31) (Fig. 2e). Stage III patients experienced a notable reduction in cumulative relative abundance of MET-4 taxa post-CRT when compared to stage I-II: mean 0.28 (±0.03) to 0.22 (±0.11) vs 0.27 (±0.09) to 0.26 (±0.12), respectively, although they were non-significant (p = 0.47) (Fig. 2f). No significant differences in MET-4 RA baseline versus post-CRT was observed stage I-II (p value = 0.81). When comparing the changes in MET-4 taxa at baseline vs post-CRT timepoints between ROMA-2 (both exogenous and endogenous) vs ROMA-1 (endogenous only, since there was no intervention) datasets across stage subgroups, cumulative relative abundance was increased post-CRT in stage III patients from ROMA-2 (intervention) while it decreased in ROMA-1, although these differences did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 2g).

Impact of MET-4 and CRT on tumor swabs and stool microbiome composition

There were no longitudinal changes in Shannon diversity index in stool samples across timepoints (Fig. S6A). No correlation was observed between stool Shannon diversity at baseline and MET-4 taxa increase at subsequent timepoints. Overall stool community composition by Bray-Curtis dissimilarity did not differ across timepoints (Fig. S6B), although a few taxa were differentially abundant at post-CRT timepoints when compared to baseline (Fig. S6C–E).

MET-4 taxa were rare in tumor swabs at all timepoints with no significant changes in the cumulative relative abundance (p = 0.089) (Fig. S6F). Mean (±standard deviation) cumulative relative abundance of MET-4 taxa at baseline was 0.005 ± 0.01. There were no longitudinal changes in Shannon diversity index in tumor swabs across timepoints (Fig. S6G). Overall tumor swab community composition significantly differed by sampling timepoint (p = 0.003) (Fig. S6H), with several differentially abundant taxa noted at week 4 and 2-month follow-up timepoints when compared to baseline (Fig. S6I–K).

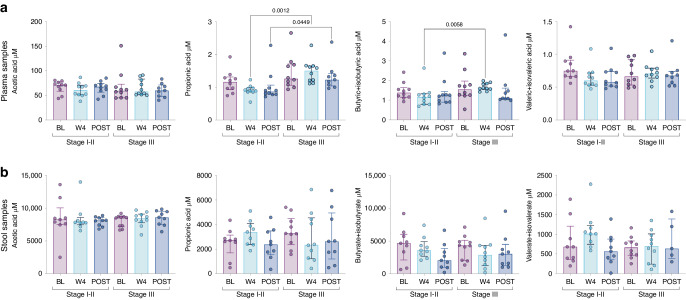

Metabolomic analysis were consistent with microbiome observations

Ecological interventions targeting gut microbiome can lead to changes in stool/plasma metabolomes [4, 9], we therefore investigated the variations in bile acids and short-chain fatty acids in both stool and plasma samples available at baseline (n = 19 and n = 20, respectively), week 4 (n = 19 and n = 20, respectively) and post-CRT (n = 18 and n = 19, respectively) for all patients. No significant differences were observed in stool nor plasma primary and secondary bile acids and short-chain fatty acids following MET-4 at week 4 or post-CRT (Fig. S7). There was no correlation between increased MET-4 cumulative relative abundance and metabolomic changes. Given the higher cumulative relative abundance of MET-4 taxa observed in patients with stage III disease, we explored metabolomic changes according to stage subgroups. Butyrate and propionic short-chain fatty acids were significantly higher in plasma samples at week 4 in stage III patients when compared to stage I-II (p = 0.03 and p < 0.01, respectively) (Fig. 3a), while they both tended to decrease in stool samples (Fig. 3b). Bile acids did not differ between stage subgroups across timepoints, but a consistent decrease in secondary bile acids at week 4 was noted in stage III but not stage I-II patients (Fig. S8). These findings may indicate that changes in MET-4 cumulative RA in stools are associated with metabolic changes in plasma.

Fig. 3. Plasma and stool short chain fatty acids exploratory analysis in stage subgroups.

a, b Short chain fatty acid (SCFA) levels in plasma and stool samples, respectively, at each timepoint and by stage subgroups. P values are only shown when significant (p < 0.05).

We attempted to account for the effect of dietary habits through collection of validated questionnaires, however, the small number of patients and the high heterogeneity of the data gathered limited its evaluation.

Discussion

ROMA-2 is the first interventional study to evaluate microbiome modulation in the context of CRT in HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer patients. We showed that MET-4 is safe and tolerable in this patient population and setting, and it does not increase risk or severity of CRT-induced toxicity. MET-4 administration was feasible during the first 3 weeks of CRT, although completion of dosing was limited by impaired oral intake due to CRT toxicity. In terms of ecological response, there was no significant increase in MET-4 taxa cumulative relative abundance nor absolute count occurred at any timepoint post- intervention in the overall cohort, although the exploratory subgroup analysis revealed significant increases in MET-4 taxa in most stage III patients when compared to stage I-II. Changes in both plasma and stool targeted metabolomes were observed in this patient subgroup.

Gut microbiome manipulation with oral FMT alternatives including dietary changes, pre- and pro-biotics and oral administration of single strains is being actively investigated in cancer patients, mostly in the context of immunotherapy-based treatments [6, 17]. In patients with advanced cancer, a few studies evaluating oral consortia in combination with antiPD-(L)1 and antiCTLA-4 agents are ongoing (NCT04208958, NCT03686202), with MET4 -IO trial being the first published report in this setting [9]. Similarly to other early phase microbiome-modulating studies, the main primary endpoint of MET4-IO, was to demonstrate “engraftment” or ecological response defined as an increase in MET-4 taxa relative abundance in patients’ stools at pre-specified timepoints post-administration. The study showed a significant increase in relative abundance as in the absolute number of MET-4 taxa in several MET-4 recipients when compared to controls, but failed to demonstrate significant changes post-MET-4 intervention when compared to baseline within MET-4 recipients. The evaluation of engraftment in this ROMA-2 study was built upon the design and preliminary data from the MET4-IO trial. We did not observe a consistent and significant increase in MET-4 relative abundance at week 4 or subsequent timepoints across all recipients. The lack of engraftment observed in our study may be due to multiple factors: ecological resistance due to the composition of the pre-treatment gut microbiome composition, comorbidities, the use of concurrent therapies and dose/duration of MET-4 administration. In the ROMA-1 study, CRT cper se did not appear to induce significant changes in gut microbiome composition and diversity, while it clearly impacted on oral microbiome composition [13]. In ROMA-2 we did observe an increase in MET-4 cumulative abundance in at least one timepoint post-MET4 intervention in 75% of the patients, although this change did not appear to be driven by specific MET-4 taxa and varied by patient. The measurement of engraftment is not standardized in the microbiome field, with different methodology (i.e., increment in cumulative relative abundance or in the absolute count of a specific taxon; detection of endogenous vs exogenous taxa) reported. What is considered a “positive” ecological response remains challenging and ideally will be linked to physiologic, metabolomic or immunologic biomarkers of microbiome function. The lack of a standardized or externally validated ecological response method limits the ability to reliably or reproducibly correlate findings with a clinically meaningful endpoint (i.e., response rate, survival) and the potential of microbiome responses to become a pharmacodynamic biomarker. Ecological parameters may not be the most predictive measure of microbiome-modifying therapeutic efficacy. Metabolic changes, treatment-induced anti-microbial antibodies and immunologic parameters are potentially more informative indicators of microbiome-targeting therapeutic responses in the setting of ICI [18].

How to pre-identify patients that may respond to microbiome modulation strategies remains unknown, since there are many potential factors influencing individual changes in gut microbiome composition pre- and during interventions, such as comorbidities, prior anticancer therapies or use of specific concomitant medications such as antibiotics [19, 20]. Although pre-selection of patients based on a disrupted/unfavorable gut microbiome can be technically feasible, defining what bacteria could be used as a biomarker for a specific antitumor immune-mediated response is complex, and it would not account for dynamic/transient changes [21]. The administration of selected antibiotics pre-microbiome intervention with the aim of reducing inter-patient variability and facilitate the engraftment of administered bacteria is under evaluation (NCT04208958). In the MET4-IO trial, changes in MET-4 cumulative relative abundance varied significantly by patient [9]. The subgroup exploratory analysis in ROMA-2 identified a potential group of ecological responders: a higher number of patients with stage III disease had an increase in MET-4 cumulative relative abundance at week 4 when compared to patients with stage I or II; and overall MET-4 taxa abundance at week 4 was significantly higher in these patients when compared to stage I-II. These observations in stage III patients were linked with changes in stools and plasma metabolites, mainly in plasma and stool short-chain fatty acids. Several taxa included in the MET-4 consortia are known to be producers of short-chain fatty acids such as Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Clostridium leptum and Eubacterium rectale [22]. Short-fatty acids, particularly butyrate, have immunomodulatory properties, especially by modulating T-regulatory T cells, and its abundance in both plasma and stools has been recently correlated with responses to antiPD-1 agents [23, 24]. However, the significance of these metabolome changes is unclear in this patient population, since we cannot rule out a potential impact of other factors such as cisplatin chemotherapy or dietary changes (enteral nutrition).

Interestingly, the comparative analysis with our prior observational cohort (ROMA-1 study, [12]), revealed that CRT induced a notable reduction of the MET-4 relative abundance of taxa in stools in stage III patients but not stage I-II, while this did not occur in the ROMA-2 study, suggesting that MET-4 intervention may have prevented the decrease in endogenous “immune-favorable taxa” associated with CRT in this subgroup of patients. These findings may have clinical implications, since patients with stage III HPV-related OPC are considered a “high risk” subgroup, as the rates of disease recurrence are higher when compared to stage I-II patients, and they are the target for treatment intensification strategies involving the use of ICI in combination with CRT.

There are several limitations in this trial. The ROMA-2 was designed as a feasibility study and the observations and findings are exploratory and hypothesis generating. Given the limited number of patients, our study does not have power to assess the impact of potential confounders and variables that may explain the differential ecological responses to MET-4 across stage subgroups. In particular, altered nutrition may have impacted on MET-4 ecological responses, although in the ROMA-1 study its use did not appear to alter the composition nor diversity of the gut microbiome composition [12]. The study lacks a randomized control group to assess the variability directly caused by the effect of CRT, and we recognize the potential bias of using the prior non-interventional cohort of LA-OPSCC patients as a comparator. The association between microbiome compositional changes and disease recurrence was out of the scope of this study, and it could not be explored given the small cohort, the limited number of recurrences and the short follow-up for a curative-intent patient population. We could not evaluate the correlation between changes in MET-4 taxa and tumor immunophenotyping as we did not collect tumor biopsies post-MET 4 intervention. Finally, 16 S RNA sequencing provides lower taxonomic resolution than alternatives such as metagenomics, which thus does not allow us to differentiate species within some genera, or to distinguish between endogenous or exogenous MET-4 strains.

Overall, the ROMA-2 study confirmed the feasibility, safety and tolerability of gut microbiome intervention with an oral microbial consortium in the context of definitive CRT in patients with HPV-related OPSCC. The ecological responses and the metabolome changes observed in patients with stage III disease may warrant further exploration of microbiome therapeutic interventions in this subgroup.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all patients and their families for their participation. We acknowledge and are grateful for the support of the Head and Neck Discovery Program, the Tomcyzk AI and Microbiome Working Group, the Bartley-Smith/Wharton, the Gordon Tozer, the Wharton Head and Neck Translational, Dr. Mariano Elia, Petersen-Turofsky Funds and the ‘The Joe & Cara Finley Center for Head & Neck Cancer Research’ at the Princess Margaret Cancer Foundation. MO would like to acknowledge the SEOM Foundation and Cris Contra el Cancer Foundation for their financial-grant support of his fellowship at Princess Margaret Cancer Center; and the Conquer Cancer Foundation 2019 Young Investigator Award, Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ICIII) Rio Hortega Pre-Doctoral Program and M-AES research support grants and Dr. Spreafico Research Funding to the ROMA Project.

Author contributions

MO, LLS, BC and AS developed the concept and design of the ROMA LA-OPSCC-002 study. Patient recruitment and sample collection was performed by MO, GW, AS, LLS, RT and AH. Clinical data collection, analysis and curation was performed by MO, GW and AS. KC performed 16 S qPCR quantification, sequencing library preparation and taxonomic profiling (with CAGEF). MO, AH and AR conducted microbiome statistical analyses and figure generation under supervision of BC.

Funding

This study was partly supported by MO ASCO Conquer Cancer Foundation Young Investigator Award (YIA) 2019, by the Princess Margaret Hospital DMOH 2019 Grant and by AS Division of Medical Oncology, Department of Medicine, University of Toronto Strategic Planning Innovation Grant.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study will be made available in public repository. OTU tables are provided in the Supplementary Material.

Competing interests

MO has consulting/advisory arrangements with Merck, MSD and Transgene. Research support from Merck and Roche. The institution receives clinical trial support from Abbvie, Ayala Pharmaceutical, MSD, ALX Oncology, Debiopharm International, Merck, ISA Pharmaceuticals, Roche Pharmaceuticals, Boehringer Ingelheim, Seagen, Gilead. Travel accommodations expenses: BMS, MSD, Merck. AS has consulting/advisory arrangements with Merck, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, Oncorus, Janssen, Medison & Immunocore. The institution receives clinical trial support from: Novartis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Symphogen AstraZeneca/Medimmune, Merck, Bayer, Surface Oncology, Northern Biologics, Janssen Oncology/Johnson & Johnson, Roche, Regeneron, Alkermes, Array Biopharma/Pfizer, GSK, Treadwell, ALX Oncology, Amgen, Servier. RMN has consulting/advisory arrangements with Merck, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Roche, Seattle Genetics, Astra Zeneca, Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim. Speaker Bureau honoraria from Merck, MSD and Boehringer Ingelheim. GW has consulting/advisory arrangements with Gilead, Novartis, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Boehringer-Ingelheim. Research support from Pfizer. Travel grants from BMS, Abbvie.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

ROMA LA-OPSCC-002 was a prospective interventional trial that involved MET-4 drug administration and the collection and analysis of oropharyngeal swabs, stool and plasma samples. The study did not determine the eligibility to receive standard-of-care treatment with definitive chemoradiotherapy. The study was approved by the Princess Margaret Cancer Center Institutional Research Ethics Board (Study ID 19-5079.10) and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided written, signed, informed consent to participate.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Bryan Coburn, Email: bryan.coburn@uhn.ca.

Anna Spreafico, Email: anna.spreafico@uhn.ca.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41416-024-02701-y.

References

- 1.Routy B, Le Chatelier E, Derosa L, Duong CPM, Alou MT, Daillere R, et al. Gut microbiome influences efficacy of PD-1-based immunotherapy against epithelial tumors. Science. 2018;359:91–7. doi: 10.1126/science.aan3706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gopalakrishnan V, Spencer CN, Nezi L, Reuben A, Andrews MC, Karpinets TV, et al. Gut microbiome modulates response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in melanoma patients. Science. 2018;359:97–103. doi: 10.1126/science.aan4236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davar D, Dzutsev AK, McCulloch JA, Rodrigues RR, Chauvin JM, Morrison RM, et al. Fecal microbiota transplant overcomes resistance to anti-PD-1 therapy in melanoma patients. Science. 2021;371:595–602. doi: 10.1126/science.abf3363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baruch EN, Youngster I, Ben-Betzalel G, Ortenberg R, Lahat A, Katz L, et al. Fecal microbiota transplant promotes response in immunotherapy-refractory melanoma patients. Science. 2021;371:602–9. doi: 10.1126/science.abb5920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marcella C, Cui B, Kelly CR, Ianiro G, Cammarota G, Zhang F. Systematic review: the global incidence of faecal microbiota transplantation-related adverse events from 2000 to 2020. Aliment Pharm Ther. 2021;53:33–42. doi: 10.1111/apt.16148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Araujo DV, Watson GA, Oliva M, Heirali A, Coburn B, Spreafico A, et al. Bugs as drugs: the role of microbiome in cancer focusing on immunotherapeutics. Cancer Treat Rev. 2020;92:102125. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2020.102125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Louie T, Golan Y, Khanna S, Bobilev D, Erpelding N, Fratazzi C, et al. VE303, a defined bacterial consortium, for prevention of recurrent clostridioides difficile infection: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2023;329:1356–66. doi: 10.1001/jama.2023.4314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van der Lelie D, Oka A, Taghavi S, Umeno J, Fan TJ, Merrell KE, et al. Rationally designed bacterial consortia to treat chronic immune-mediated colitis and restore intestinal homeostasis. Nat Commun. 2021;12:3105. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-23460-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spreafico A, Heirali AA, Araujo DV, Tan TJ, Oliva M, Schneeberger PHH, et al. First-in-class microbial ecosystem therapeutic 4 (MET4) in combination with immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with advanced solid tumors (MET4-IO trial) Ann Oncol. 2023;34:520–30. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2023.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oliva M, Spreafico A, Taberna M, Alemany L, Coburn B, Mesia R, et al. Immune biomarkers of response to immune-checkpoint inhibitors in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Ann Oncol. 2019;30:57–67. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Orlandi E, Iacovelli NA, Tombolini V, Rancati T, Polimeni A, De Cecco L, et al. Potential role of microbiome in oncogenesis, outcome prediction and therapeutic targeting for head and neck cancer. Oral Oncol. 2019;99:104453. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2019.104453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oliva M, Schneeberger PHH, Rey V, Cho M, Taylor R, Hansen AR. Transitions in oral and gut microbiome of HPV+ oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma following definitive chemoradiotherapy (ROMA LA-OPSCC study). Br J Cancer. 2021;124:1543–1551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Oliva Bernal M, Schneeberger PHH, Taylor R, Rey V, Hansen AR, Taylor K, et al. Role of the oral and gut microbiota as a biomarker in locoregionally advanced oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (ROMA LA-OPSCC) J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:6045. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2019.37.15_suppl.6045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wong KCW, Johnson D, Hui EP, Lam RCT, Ma BBY, Chan ATC. Opportunities and challenges in combining immunotherapy and radiotherapy in head and neck cancers. Cancer Treat Rev. 2022;105:102361. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2022.102361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Callahan BJ, McMurdie PJ, Rosen MJ, Han AW, Johnson AJ, Holmes SP. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat Methods. 2016;13:581–3. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bolyen E, Rideout JR, Dillon MR, Bokulich NA, Abnet CC, Al-Ghalith GA, et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat Biotechnol. 2019;37:852–7. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0209-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spencer CN, McQuade JL, Gopalakrishnan V, McCulloch JA, Vetizou M, Cogdill AP, et al. Dietary fiber and probiotics influence the gut microbiome and melanoma immunotherapy response. Science. 2021;374:1632–40. doi: 10.1126/science.aaz7015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dizman N, Meza L, Bergerot P, Alcantara M, Dorff T, Lyou Y, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab with or without live bacterial supplementation in metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a randomized phase 1 trial. Nat Med. 2022;28:704–12. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01694-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eng L, Sutradhar R, Niu Y, Liu N, Liu Y, Kaliwal Y, et al. Impact of antibiotic exposure before immune checkpoint inhibitor treatment on overall survival in older adults with cancer: a population-based study. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41:3122–34. doi: 10.1200/JCO.22.00074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang C, Feng S, Huo F, Liu H. Effects of four antibiotics on the diversity of the intestinal microbiota. Microbiol Spectr. 2022;10:e0190421. doi: 10.1128/spectrum.01904-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rooney AM, Cochrane K, Fedsin S, Yao S, Anwer S, Dehmiwal S, et al. A microbial consortium alters intestinal Pseudomonadota and antimicrobial resistance genes in individuals with recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection. mBio. 2023;14:e0348222. doi: 10.1128/mbio.03482-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Louis P, Flint HJ. Formation of propionate and butyrate by the human colonic microbiota. Environ Microbiol. 2017;19:29–41. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mirzaei R, Afaghi A, Babakhani S, Sohrabi MR, Hosseini-Fard SR, Babolhavaeji K, et al. Role of microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids in cancer development and prevention. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021;139:111619. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2021.111619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nomura M, Nagatomo R, Doi K, Shimizu J, Baba K, Saito T, et al. Association of short-chain fatty acids in the gut microbiome with clinical response to treatment with nivolumab or pembrolizumab in patients with solid cancer tumors. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e202895. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.2895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study will be made available in public repository. OTU tables are provided in the Supplementary Material.