Advocates of tobacco control worldwide have long suspected collusion among major international tobacco companies over their refusal to acknowledge that smoking causes lung cancer, heart disease, emphysema, and other serious diseases. Tobacco industry documents now available on the internet disclose the establishment of a conspiracy between Philip Morris, R J Reynolds, British-American Tobacco, Rothmans, Reemtsma, and UK tobacco companies Gallaher and Imperial, dating from 1977. The documents also disclose the objects of the conspiracy: basically, to protect the industry's commercial interests both by promoting controversy over smoking and disease and through strategies directed at reassuring smokers.

The documents also disclose the means of implementing the conspiracy by utilising national manufacturers' associations coordinated through the International Committee on Smoking Issues, later to become the International Tobacco Information Centre. We expose the formation of the conspiracy and its objectives and means of implementation over the ensuing decades.

Summary points

For decades international tobacco companies have denied or disputed that smoking causes serious diseases, and advocates of tobacco control worldwide have long suspected collusion over this issue

Internal documents from the tobacco industry now available on the internet disclose that in 1977 seven of the world's major tobacco companies conspired to promote “controversy” over smoking and disease, in an exercise called Operation Berkshire

This conspiracy resulted in the International Committee on Smoking Issues (subsequently the International Tobacco Information Centre), which operated though an internationally coordinated network of national manufacturers' associations to retard measures for tobacco control

Thousands of documents now available on the internet evidence the implementation of the objectives of Operation Berkshire

Methods

After learning of a document referring to “Operation Berkshire,” we searched for documents on the website tobaccoarchives.com, and we collected and reviewed documents relevant to the conspiracy between the major tobacco companies and to its objectives and implementation.1 The website provides access to document sites on which various tobacco companies have been required to post copies of documents as a result of the multiparty settlement of litigation by United States attorneys general.2

An initial search of the Philip Morris site using the term “Berkshire” produced 157 documents of which the vast majority related to the conspiracy. Subsequent searches using the term “Shockerwick”, especially on the Philip Morris and R J Reynolds sites, filled in the gaps. Further searches using the terms “ICOSI” (International Committee on Smoking Issues) and “INFOTAB” (International Tobacco Information Centre) yielded thousands of additional documents on almost all the sites. Documents found under “Berkshire” and “Shockerwick” exposed the formation of a conspiracy and its objectives. Documents found under “ICOSI” and “INFOTAB” were too numerous to explore in the time available, but any number of them illustrate the implementation of the conspiracy.

Formation of the conspiracy

On 3 December 1976, the then President of Philip Morris International, Hugh Cullman, received a telephone call from the then Chairman of Imperial Tobacco in the United Kingdom, Mr A G (Tony) Garrett, who proposed a meeting of the world's major tobacco companies to develop a unified “defensive strategy” on smoking issues. A Philip Morris memorandum records:

Tony Garrett (TG) Chairman of Imperial Tobacco Limited phoned me from London. TG informed me that he had been exploring with a number of major tobacco companies; specifically, B.A.T., R.J. Reynolds, Reemtsma, Rothmans International and now with Philip Morris International, whether we might be prepared to meet discreetly to develop a defensive smoking and health strategy for major markets such as the U.K., Germany, Canada, U.S. and possibly others. TG reported that B.A.T., R.J. Reynolds, Reemtsma, Rothmans International and Imperial Tobacco were prepared to consider such a program which TG suggested take place after careful preparation in April or May of 1977 . . . The meeting would be as discreet as possible with, hopefully no publicity emanating therefrom, with a public affairs statement ready should news of such a meeting leak out. The initial objective of this group was to develop a smoking and health strategy which would include a voluntary agreement that no concessions beyond a certain point would be voluntarily made by the members and if further concessions were required by respective governments, that these not be agreed to and that governments be forced to legislate. TG seemed to be most concerned that companies and countries would be picked off one by one and that the Domino theory would impact on all of us.3

Garrett followed up the conversation with a letter outlining the proposal under the code name “Operation Berkshire.” He noted that he had received support for the idea from British-American Tobacco, R J Reynolds, Reemtsma, and Rothmans International and proposed the meeting could be held at Shockerwick House, near Bath, England.4 Subsequently, Imperial Tobacco wrote to prospective attendees on 24 March 1977 outlining the programme and enclosing a bogus press statement.5,6

A position paper jointly prepared by British-American Tobacco and Philip Morris was circulated under cover of a letter stressing “the need for confidentiality and security” as neither company “would wish the paper to fall into the wrong hands.” This paper proceeded on the assumption of “a continuing smoking and health controversy,” involved a refusal to “accept as proven that there is a causal relationship between smoking and various diseases,” and maintained that “the issue of causation remains controversial and unresolved.7,8 It seems that a major motivation was fear of legal liability, particularly in the United States.9

MATTHEW PETERS

Despite this, industry documents from around the time disclose that senior officials within the industry took a different view.10 This view differed to such an extent that by 1980 documents from British-American Tobacco rehearsed “possible positions on smoking and health”11 and canvassed “a new company approach to the smoking and health issue.”12

Objectives of the conspiracy

The agenda for Operation Berkshire included determining areas for future cooperation in matters relating to smoking and health, discussing the feasibility of joint industry research into the benefits of smoking, and mounting a programme of “smoker reassurance” to counter the increasing social unacceptability of smoking.13,14 Proceedings from the meeting on 2 and 3 June 1977 are recorded in a minute apparently prepared by a representative of Philip Morris Europe.15 The minute, headed “strictly confidential—limited circulation,” describes a presentation by Imperial Tobacco, which “by implication rather than direct admission, made concessions in the areas of Lung Cancer, Pregnancy and to a lesser extent, Coronary Heart Disease.” This was followed by a “full discussion” of the Philip Morris and British-American Tobacco position paper and the ready acceptance of a “parallel paper” tabled by R J Reynolds.

A memorandum by R J Reynolds about the meeting describes—in even more detail than the minute of Philip Morris Europe—the deliberations and resolutions of the senior representatives of the tobacco industry in attendance.16 The record by Philip Morris of the meeting notes an agreement to establish three working parties dealing with the social acceptability of smoking, the benefits of smoking, and “other possible causes of alleged smoking related diseases.”15 It recommended that:

Philip Morris regards Operation Berkshire as a turning point in international cooperation on a matter of vital concern to the industry

Philip Morris attempts to maximise the effectiveness of the three established working committees by including executives with experience beyond purely the scientific or legal disciplines

Full security cover be maintained for future meetings irrespective of numbers of executives involved

The agreed position paper becomes the vehicle to activate industry associations throughout the world.

In time, this group of international executives from the tobacco industry became known as the International Committee on Smoking Issues.17,18

Implementation of the conspiracy

After the meeting, the working parties set about their tasks. Of particular interest is the record of a meeting of the working party on medical research that took place on 21 and 22 July. A memorandum from Helmut Gaisch, the delegate for Philip Morris Europe, summarised the meeting as follows:

At the beginning of the meeting we almost came to a deadlock. In discussing causality, a complete division of opinion occurred: Drs. Bentley, Field and Felton on the one side and Dr. Colby and myself on the other with Dr. Melch and Mr Hatchett remaining indifferent. The reason was that the three representatives of the British companies accepted that smoking was the direct cause of a number of diseases. They shared the opinion held by the British medical establishment that a consistent statistical association between one risk factor and a disease was sufficient to be able to assume causality. Dr. Colby and I emphasised, however, that the existence of a statistical association between a number of disease categories with a wide range of variables (risk markers or risk factors)—many of which have not even been recorded with sufficient accuracy—can, on principle, not serve to establish causality.19

Again, an even more detailed memorandum from R J Reynolds records the dissent in this meeting.20 Some consensus was, however, reached and a report prepared, essentially with the Philip Morris and R J Reynolds position prevailing.21 Apparently there was considerable acrimony between senior scientists in at least two of the companies (R J Reynolds and British-American Tobacco).22

Task forces

A second meeting of the International Committee on Smoking Issues was held at Brillancourt, Lausanne, Switzerland, 11 and 12 November 1977. Here, a revised position paper was adopted, working parties' reports received, and a “task force program” devised.23 One resolution involved an acceptance of the need for fully supported national associations of cigarette manufacturers such as tobacco institutes. This also involved the expression of the belief “that the Industry's activities in the smoking and health field should be carried out by or through the Associations, whenever this is appropriate.” In 1978, a secretariat was established in Brussels for the International Committee on Smoking Issues and a charter was ratified at a meeting at Leeds Castle.24–26 Task forces were also established to monitor world conferences on smoking and health.27

In 1981 the committee became known as the International Tobacco Information Centre.28 Thereafter, the centre established steering groups for subsequent world conferences and other task forces to undermine public health efforts to convey the dangers associated with smoking.28,29

National manufacturers' associations

The International Committee on Smoking Issues and International Tobacco Information Centre fostered the establishment of the national manufacturers' associations, and a joint meeting of these associations was convened in Zurich, 20-3 May 1979.30 One of the first countries to establish a national manufacturers' association was Australia, where the Tobacco Institute of Australia was established in December 1978. By 1981 there were 28 national manufacturers' associations in North America, Europe, Australia, New Zealand, Africa, the Middle East, Latin America, and the Far East including the Indian subcontinent.31

Operation Mayfly

“Operation Mayfly” illustrates the role of the national manufacturers' associations. This project, conceived by the International Tobacco Information Centre, was for a “long term communications plan” implemented in response to the World Health Organization's campaign “Smoking or health—the choice is yours.”32 Operation Mayfly involved a 1981 “field test” utilising the tobacco institutes of Australia and New Zealand “. . . to influence, modify or change public opinion to the industry, smokers and smoking, to create a more favourable climate however directly or indirectly.”33

Industry knowledge

All of this conduct occurred over the last three decades of the 20th century, despite recent admissions of an overwhelming medical and scientific consensus that cigarette smoking causes serious disease, and despite the fact that this seems to have been accepted—at least by the British tobacco companies—since the late 1970s.34–36 This is confirmed by another document recording notes on a research and development conference by British American Tobacco (BAT) Group in Sydney, March 1978:

There has been no change in the scientific basis for the case against smoking. Additional evidence of smoke-dose related incidence of some diseases associated with smoking has been published. But generally this has long ceased to be an area for scientific controversy. Against this background members were concerned that the approach by ICOSI . . . seemed to imply that research solutions should no longer be sought for smoking products and that, if adopted, the ICOSI programme would drain resources from scientifically useful areas of product modification into areas of dubious or no scientific value. The meeting affirmed that cigarettes acceptable on all counts can probably be achieved by research and, indeed, may in fact be available. The ICOSI concern to replicate the established multiple aetiology for some diseases seems of particularly little value.37

Indeed, discussion within the industry dating back at least 40 years shows that it had long contemplated “coming clean” on the causal issue, at least for heavy smokers. A British American Tobacco document dated 16 May 1980 states:

The company's position on causation is simply not believed by the overwhelming majority of independent observers, scientists and doctors . . . The industry is unable to argue satisfactorily for its own continued existence, because all arguments eventually lead back to the primary issue of causation, and on this point our position is unacceptable . . . our position on causation, which we have maintained for some twenty years in order to defend our industry is in danger of becoming the very factor which inhibits our long term viability.38

This document also discusses the disadvantages and advantages of making admissions on the causal issue, and concludes [to] “continue to maintain our present position on causation” or:

we can move our position on causation to one which acknowledges the probability that smoking is harmful to a small percentage of heavy smokers . . . On balance, it is the opinion of this department that . . . we should now move to position B, namely, that we acknowledge ‘the probability that smoking is harmful to a small percentage of heavy smokers’ . . . The ideas suggested above are in some cases a radical departure from our current practice although nearly all of them have echoes in our overall policy and attitudes. The problem to date has been the severe constraint of the American legal position. This problem has made us seem to lack credibility in the eyes of the ordinary man in the street. Somehow we must regain this credibility. By giving a little we may gain a lot. By giving nothing we stand to lose everything.38

On the tobacco archives website, there are thousands of documents showing the activities of the International Committee on Smoking Issues and International Tobacco Information Centre.1 These include many revealing frustration over the lack of credibility in promoting “social acceptability” of smoking against the constraint of the “public position” of an ongoing controversy over smoking and disease.39

Conclusion

It would seem that the activities of the International Committee on Smoking Issues and International Tobacco Information Centre in creating a “smoking and health controversy” have been, and for over two decades have been known by the tobacco industry to be, entirely spurious. Likewise, the promotion of the controversy by national manufacturers' associations has been calculating and disingenuous. Without question, the creation and promotion of this controversy, and the adoption of strategies implementing the conspiracy resulting from Operation Berkshire, have greatly retarded tobacco control measures throughout the world.40 We hope that our analysis, and the capacity to use website links to locate documents and conduct searches, will assist in uncovering the conspiracy as it has been implemented country by country.

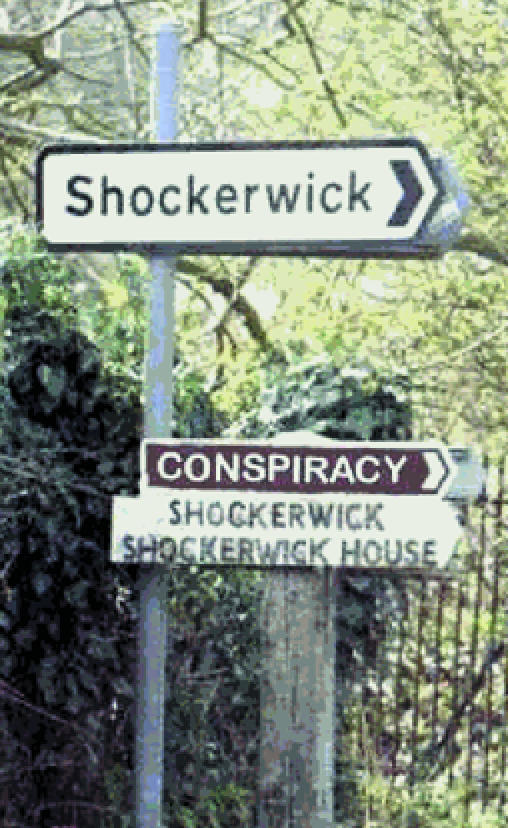

Figure.

MATTHEW PETERS

Shockerwick House, site of “Operation Berkshire”

Acknowledgments

We thank Anne Landman, regional programme coordinator and editor of the DOC-ALERT list service sponsored by the American Lung Association of Colorado, and Smokescreen for helping to find documents. Matthew Peters supplied the photographs electronically; the signpost was “enhanced.”

Footnotes

Competing interests: SC is a member of the Tobacco Control Coalition, which is bringing an action against the tobacco industry in the federal court of Australia. NF is counsel for the Tobacco Control Coalition in those proceedings.

Tables detailing shareholders votes against tobacco issues appear on the BMJ's website

References

- 1.www.tobaccoarchives.com/main.html (accessed14 Feb 2000).

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About tobacco industry documents. www.cdc.gov/tobacco/industrydocs/about.htm (accessed 27 May 2000).

- 3.Cullman H. Memorandum to the files (confidential). Interoffice correspondence, 1976: Dec 3. www.pmdocs.com Bates No 2025025286 (accessed 16 Feb 2000).

- 4.Garrett RA (Imperial Tobacco). Letter to Cullman H (Philip Morris International). www.pmdocs.com Bates No 2025025290/5291 (accessed 16 Feb 2000).

- 5.Garrett RA (Imperial Tobacco). Letter to Holtzman A (Philip Morris International). www.pmdocs.com Bates No 2025025341/5343 (accessed 16 Feb 2000).

- 6.Anon. Draft press statement (undated). www.pmdocs.com/PDF/1000219803.PDF (accesssed 16 Feb 2000).

- 7.Lockhart GHS (British American Tobacco). Letter to Garrett RA (Imperial Tobacco), 1977: Apr 28. www.pmdocs.com Bates No 2501024571 (accessed 15 Feb 2000).

- 8.Anon. Position paper, 1977: Apr 28. www.pmdocs.com Bates No 2501024572/4575 (accessed 15 Feb 2000).

- 9.Osdene TS. Roper study proposal to tobacco institute, 1978:Feb 16. www. tobaccoinstitute.com Bates No 34601/4602 (accessed 27 May 2000).

- 10.M.J.L., G.F.T. British American Tobacco. Possible positions on smoking and health. Does BAT think that smoking causes diseases such as cancer? Appendix A2;1980: May 15. http://outside.cdc.gov:8080/BASIS/ncctld/web/abindex4/sf Bates No 109881333-4 (accessed 27 May 2000).

- 11.British American Tobacco, secret—appreciation—draft No 3, a new company approach to the smoking and health issue, 1980: May 16 (accessed 27 May 2000).

- 12.http://outside.cdc.gov:8080/BASIS/ncctld/web/abindex4/sf Bates No 109881335 (accessed 27 May 2000).

- 13.Anon. Operation Berkshire, 1977: Apr 15. pmdocs.com Bates No 2501024570 (accessed 15 Feb 2000).

- 14.Anon. Operation Berkshire. Agenda papers, 1977: 30 May. www.pmdocs. com Bates No 2025025356 (accessed 16 Feb 2000).

- 15.Anon (strictly confidential—limited circulation). Brief notes on Operation Berkshire—Shockerwick House, 1977: Jun 2 and 3. www.pmdocs.com Bates No 2024266422/6428 (accessed 14 Feb 2000).

- 16.Witt SB III. Draft report to Hobbs WD and Pederson JR. International Committee on Smoking Issues, Shockerwick House, 1977: Jun 8. www.rjrtdocs.com Bates No 50029 8104/8115 (accessed 27 May 2000).

- 17.Anon. International Committee On Smoking Issues (ICOSI) Working Party on Smoking Behaviour. Chelwood, 1977: Sep 1-3. www.pmdocs. com Bates No 2501020219 (accessed 27 May 2000).

- 18.Anon. Working party on the social acceptability of smoking issue. Background, objectives, and procedures, 1977. www.pmdocs.com Bates No 2025025295/5300 (accessed 27 May 2000).

- 19.Gaisch H (Philip Morris). Letter to Wakeman HR and Fagan R (Philip Morris), 1977: Aug 12. www.pmdocs.com Bates No 1003727234/7235 (accessed 18 Feb 2000).

- 20.Colby FG. Draft notes re meeting of the working party on medical research of the International Committee on Smoking Issues, Shockerwick House, 1977: Jul 21-2; 1977: Jul 28. www.rjrtdocs.com Bates No 50029 8811/8819 (accessed 27 May 2000).

- 21.Anon. International Committee on Smoking Issues. Working party on medical research. First report (confidential), 1977. www.pmdocs.com Bates No 2501020187 (accessed 15 Feb 2000).

- 22.Memorandum for the record/file re telephone conversation between Dr Bentley and Dr Colby, 1978: Jun 1. www.rjrtdocs.com Bates No 500284646/4647 (accessed 27 May 2000).

- 23.Anon. The second ICOSI meeting, Brillancourt, Lausanne, 1977: Nov 11. www.pmdocs.com Bates No 2501017119/7140 (accessed 27 May 2000).

- 24.International Committee on Smoking Issues. Provisional job description for the secretary general and other ICOSI staff, 1978: Apr. www.pmdocs. com Bates No 2501020317/0321 (accessed 16 Feb 2000).

- 25.Doyle J (secretary general International Committee on Smoking Issues). Letter to Simpson B (Tobacco Institute of Australia), 1979: Jul 12. www. pmdocs.com Bates No 2501015819 (accessed 16 Feb 2000).

- 26.Anon. Draft agenda for Leeds Castle meeting, 1978: Sept 11. www.pmdocs.com Bates No 2501020290 (accessed 16 Feb 2000).

- 27.Anon. ICOSI Task Force on Fourth World Conference on Smoking and Health, Kansas City Meetings, 1978: Nov 20-1. www.pmdocs.com Bates No 2501015505 (accessed 16 Feb 2000).

- 28.(Author not identified.) Speech. The role of INFOTAB. Rio de Janeiro, 1981: Nov 20. www.pmdocs.com Bates No 2501029902/9918 (accessed 27 May 2000).

- 29.Falkiewicz AW (Philip Morris) Interoffice correspondence. Talking briefs, 1987: Jul 20. www.pmdocs.com Bates No 2501046619 (accessed 27 May 2000).

- 30.International Committee on Smoking Issues. Delegates and presenters. Joint meeting of the national associations, Zurich, 1979: May 20-3. www. pmdocs.com Bates No 10040887/0893 (accessed 16 Feb 2000).

- 31.International Tobacco Information Centre. National Manufacturers' Associations (list). www.pmdocs.com Bates No 2025047961 (accessed 16 Feb 2000).

- 32.King TCH (Imperial Tobacco). Letter to Stuart Alexander (Tobacco Advisory Council, London), 1981: Jan 23. www.pmdocs.com Bates No 2025017150_7152 (accessed 16 Feb 2000).

- 33.Corner RM. Advisory group meeting material, 1980: Dec 8. www.pmdocs. com Bates No 2501023924/3950; Ogilvy and Mather “Operation Mayfly 1st draft script.” www.rjrdocs.com Bates No 50212 0575_0597 (accessed 27 May 2000).

- 34.Covington MW, Egerton RAD, Hargrove GC, Horrigan EA Jr, McCay CR, Murray W, et al. Report: the public position question, 1981: Jan 26. www.pmdocs.com Bates No 2501023745/3761 (accessed 27 May 2000).

- 35.Philip Morris. Cigarette smoking. Health issues for smokers, 13 Oct 1999. www.philipmorris.com/tobacco_bus/tobacco_issues/health_issues.html (accessed 17 Feb 2000).

- 36.Gallaher Group. Submission to the parliamentary health committee (undated). www.gallaher-group.com/submission/submission.htm (accessed 27 May 2000).

- 37.Fernandes E. FOCUS-“No safe cigarette,” say UK tobacco firms. Reuters 2000: Jan 13.

- 38.Notes on group research and development conference, Sydney, 1978: Mar. (Restricted.) outside.cdc.gov:8080/BASIS/ncctld/web/mnimages/DDW?W=DETAILSID=1249 (accessed 17 Feb 2000).

- 39.British American Tobacco. Appreciation, re: Aim—to become stronger in tobacco, as a sound basis for further diversification, 1980: May 16. outside.cdc.gov:8080/BASIS/ncctld/web/abindex4/sf Bates No 109881322 – 109881331 (accessed 27 May 2000).

- 40.International Tobacco Information Centre. A guide for dealing with anti-tobacco pressure groups, 1989. www.pmdocs.com Bates No 250406380_3817 (accessed 27 May 2000).