Highlights

-

•

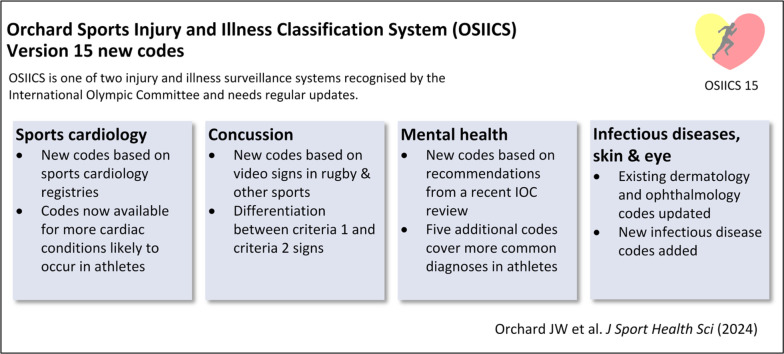

The Orchard Sports Injury and Illness Classification System (OSIICS) is 1 of 2 sports injury classification systems recognized by the International Olympic Committee and needs regular update.

-

•

It was previously focused on injuries rather than common illness/medical condition presentations in athletes, so the most recent updates have extended medical presentation diagnoses.

-

•

Version 15 includes expansion of available diagnoses in the fields of mental health, sports concussion, sports cardiology, sports dermatology, sports ophthalmology, and infectious diseases.

-

•

The OSIICS has been previously translated into Italian, Spanish, and Catalan, and further translation into multiple other languages is planned.

Keywords: Sports cardiology, Dermatology, Eye injuries, Concussion, Infectious diseases, Sports injury classification

Abstract

Background

Sports medicine (injury and illnesses) requires distinct coding systems because the International Classification of Diseases is insufficient for sports medicine coding. The Orchard Sports Injury and Illness Classification System (OSIICS) is one of two sports medicine coding systems recommended by the International Olympic Committee. Regular updates of coding systems are required.

Methods

For Version 15, updates for mental health conditions in athletes, sports cardiology, concussion sub-types, infectious diseases, and skin and eye conditions were considered particularly important.

Results

Recommended codes were added from a recent International Olympic Committee consensus statement on mental health conditions in athletes. Two landmark sports cardiology papers were used to update a more comprehensive list of sports cardiology codes. Rugby union protocols on head injury assessment were used to create additional concussion codes.

Conclusion

It is planned that OSIICS Version 15 will be translated into multiple new languages in a timely fashion to facilitate international accessibility. The large number of recently published sport-specific and discipline-specific consensus statements on athlete surveillance warrant regular updating of OSIICS.

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

The Orchard Sports Injury and Illness Classification System (OSIICS) had been used for injury surveillance for 30 years, ever since its initial iteration as the Orchard Sports Injury Classification System (OSICS, used primarily for sports injuries) in 1992. Its inception was as part of the development of the Australian Football League injury surveillance program, which commenced in 1992.1 Like other nascent injury surveillance systems around the world, it was noticed that the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) was not fit-for-purpose to use for the monitoring of sport-related presentations.2 ICD is hospital-based, which is not applicable for most sport-related injuries. The classic illustration—still relevant for the latest ICD-11—is that there is no specific code/diagnosis for a hamstring strain, a very common sports presentation.3 This also applies to many of the common lower-limb muscle strains (e.g., calf/soleus, groin/adductor). A further weakness is the provision of many codes associated with major brain trauma, such as the various types of brain hemorrhage, but no code for a medically-assessed head impact not diagnosed as a concussion (sub-concussive brain impact), which is now considered very important in sport.4 The ICD remains poor with regards to appropriate codes for many other sport-related injuries (and other musculoskeletal injury scenarios),5 hence sports injury surveillance coding has remained independent.6 Although OSIICS and Sports Medicine Diagnostic Coding System (SMDCS) are far preferable to ICD for sports injury coding, the ICD (with over 30,000 codes) has superior ability to provide specific codes for illness.7

The first known sports injuring coding system was the National Athletic Injury/Illness Reporting System8 associated with National Football League and National Collegiate Athletic Association injury surveillance, but this did not flourish as it was declared proprietary. The SMDCS has since evolved to become the most used system in North America.9 OSIICS has been used more in Australasia, and throughout Europe. Both the SMDCS and the OSIICS were chosen as official coding systems of the International Olympic Committee (IOC) in 2020,9 and categorization of body parts and systems were aligned to allow easier translation between the 2 systems.

Although OSICS had expanded its codes to better cater to illness in Version 10 (2007),10 in 2020, it was re-named OSIICS to express that illness has equal consideration to injury when coding for sporting presentations. The most recent 2022 update (Version 14)11 included coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19) codes, additional female athlete codes and, for the first time, an Italian translation. Criticism of previous sports injury classification system versions was justified based on the lack of female athlete codes,12 which had been largely redressed by OSIICS Versions 13 and 14. Version 14 also included some codes recommended by a published cycling consensus.13 Other IOC extension statements, such as tennis, golf, and football, expressed satisfaction with the available codes,14, 15, 16 along with citation by studies of pediatric injury and illness17 and inclusion in databases.18,19

Apart from being open-access and free to use (with attribution), another important strength of the OSIICS has been the frequent updates. At the 2019 IOC consensus meeting on injury and illness surveillance this was a more formal process,9 whereas the majority of updates have been ad hoc organized by the primary author,10,11,20, 21, 22 with a less formal process. This paper presents a further update (Version 15) based on relevant publications and studies that have appeared recently in the sports medicine literature.

2. Methods

It was anticipated that the IOC will eventually re-convene a larger IOC Injury Surveillance full panel in the late 2020s, but a new version was warranted in 2024 to account for areas where code evolution was needed more promptly. The author group for this update was chosen in 2023 and includes:

JWO as the founder/primary author of the OSIICS and member of the 2019 IOC consensus panel; MM as a fellow member of the 2019 IOC consensus panel and international representative on this mini-panel; JJO as a specialist expert in sports cardiology coding and head of the Australasian Registry of Electrocardiograms in National-level Athletes (ARENA) registry; ER and KMC as injury surveillance experts from the La Trobe University Sport and Exercise Medicine Research Centre, one of the Australian members of the IOC Medical Research Network.

A literature search was performed using PubMed, SPORTDiscus, and Google to search for the terms “OSIICS” or “OSICS” or “Orchard codes” or “Orchard Sports Injury Classification” from 2021 to 2023, inclusive. Reference citations for specific OSIICS publications since 2020 were also part of the search strategy (using Google Scholar citation links). Formal inclusion and exclusion criteria were not used, as the goal of the search was simply to find references that had used the OSIICS over this time period, which did not require a complicated method. The available accumulated references were then reviewed for further code recommendations, any other considerations for additional codes were taken on the expert advice of the authors.

3. Results

OSIICS (or OSICS or Orchard codes) were referenced in multiple studies published in 2022 or early 2023.23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32 One recent study suggested multiple additional codes33 and pointed to other areas with deficient medical coding, where additional diagnostic depth has been added.

3.1. Additional mental health codes

A specific study on surveillance of athlete mental health symptoms and disorders recommended 5 additional mental health codes that were not part of OSIICS Version 14.33 These new codes are included below in Table 1, along with the ICD-11 equivalents.

Table 1.

Additional mental health codes.

| Diagnosis | OSIICS 15 | ICD-11 |

|---|---|---|

| Specific phobias | MSSP | 6B03 |

| Somatization | MSXS | 6C20.Z |

| Sleep disorders | MSSS | 7A26 |

| Bipolar disorders | MSXB | 6A60 |

| Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder | MSSH | 6A05 |

Abbreviations: ICD = International Classification of Diseases; OSIICS = Orchard Sports Injury and Illness Classification System.

3.2. Additional concussion codes

Additional concussion codes have been added based on the increasing use of video signs in Rugby Union34 and other sports35 to differentiate concussion sub-categories, which influence decisions on removal from the field and return to play. Criteria (or Category) 1 concussion signs include clear loss of consciousness, ataxia or seizures, and Criteria 1 symptoms include amnesia and disorientation,34 whereas Criteria 2 concussion signs include possible loss of consciousness and possible ataxia. All of these new codes generally translate to the single ICD-11 code for concussion (NA07.0).

There has been pressure from governmental investigations into the management of concussion36 to institute more conservative minimum return-to-play times. Because some of these guidelines will rely on specific symptoms and signs, there will be generally more need to use specific diagnostic criteria, as listed in Table 2, as part of injury classification rather than simply relying on the single code of HN1. In Version 13, HZN was added to reflect a head impact that was assessed medically but was not deemed to be a concussion, given the importance of recording not only diagnosed concussions but also sub-concussive head impacts as part of injury surveillance.4

Table 2.

Additional concussion codes.

| Diagnosis | OSIICS 15 | ICD-11 |

|---|---|---|

| Concussion with Criteria 1 video signs | HNC1 | NA07.0 |

| Concussion with Criteria 2 video signs | HNC2 | NA07.0 |

| Head impact (not concussion) with Criteria 2 video signs | HZC2 | NA07.0 |

| Concussion in a player with a concerning history | HNCH | NA07.0 |

| Concussion with no concerning history or signs | HNCN | NA07.0 |

| Concussion with delayed symptom presentation | HNCD | NA07.0 |

| Concussion with imaging abnormality | HNCA | NA07.0 |

| Concussion with abnormal biomarkers | HNCB | NA07.0 |

| Traumatic encephalopathy syndrome | HNCT | NA07.0Y |

Abbreviations: ICD = International Classification of Diseases; OSIICS = Orchard Sports Injury and Illness Classification System.

3.3. Additional cardiac codes

The field of sports cardiology has emerged as a subspeciality of both cardiology and sports medicine.37 While multiple sports cardiology codes were already present in OSIICS Version 14, the Outcomes Registry for Cardiac Conditions in Athletes design protocol,38 the ARENA protocol, and a previous landmark cardiac screening paper39 were searched for sports cardiology diagnoses not already included. This process allowed the identification of further diagnoses to be added, as per Table 3.

Table 3.

Additional sports cardiology codes.

| Diagnosis | OSIICS 15 | ICD-11 |

|---|---|---|

| Arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy (formerly arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy) | MCEAC | BC43.6 |

| Dilated cardiomyopathy | MCCD | BC43.0 |

| Brugada syndrome | MCJBS | BC65.1 |

| Aortopathy | MCCA | 4A44.1 |

| Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator complication | MCZIC | NE82.1Z |

| ICD insertion | MCZII | QB50.03 |

| ICD shock | MCZIS | |

| Cardiac arrest | MCVCA | MC82 |

| Sudden cardiac death | MCZCD | |

| Hypertension | MCCH | BA00 |

| High cholesterol | MCCC | 5C80.0 |

| Commotio cordis | MCET | |

| Ablation procedure | MCZP | |

| Patent ductus arteriosus | MCJP | LA8B.4 |

| Atrial septal defect including patent foramen ovale | MCJD | LA8E.Y |

| Abnormal screening ECG | MCEG | MC91 |

| Syncopal episode(s) cardiac | MCESC | MG45.0 |

| Exertional chest pain (angina) | MCECP | BA40 |

| Marfan syndrome | MCJM | LD28.0 |

| Pacemaker insertion | MCZPM | |

| Pacemaker complication | MCZPC | |

| Heart failure | MCCHF | BD1Z |

| Syncope/collapse, general (including non-cardiac causes) | MCES | MG45.Z |

| Coronary artery anomaly | MCJCA | LA8C |

| Ventricular septal defect | MCJVS | LA88.4 |

| Mitral valve prolapse | MCCMV | BB62 |

| Pulmonary stenosis | MCCPS | BB90 |

| Aortic valve pathology | MCCAV | BB7Z |

| Supraventricular tachycardia (including atrial flutter) | MCCSV | BC8Z |

| Myocardial infarction | MCCMI | BA41.Z |

| Coronary artery disease | MCCCA | BA52.Z |

Abbreviations: ECG = electrocardiogram; ICD = International Classification of Diseases; OSIICS = Orchard Sports Injury and Illness Classification System.

It is anticipated that research projects like Outcomes Registry for Cardiac Conditions in Athletes and ARENA will need the greater diagnostic options provided by OSIICS Version 15 as part of surveillance of these cardiac conditions as they relate to athletes.

3.4. Additional dermatology, ophthalmology, and infectious disease codes

Neither dermatology40,41 nor ophthalmology42,43 codes were comprehensive in previous versions; thus, additional codes have been introduced. Versions 13 and 14 had codes for COVID-19 that were thought to have become relevant for athletes given the mandatory government restrictions in many countries in 2020–2022. Other major specific infectious diseases are included for the first time (Table 4). The full Excel version of OSIICS 15 is downloadable in the online version of this paper as Supplementary materials.

Table 4.

Additional dermatology, ophthalmology, and infectious disease codes.

| Diagnosis | OSIICS 15 | ICD 11 |

|---|---|---|

| Sebaceous (epidermoid) cyst | MDYC | EK70.0Z |

| Subcutaneous lipoma | MDBL | 2E80.0 |

| Enlarged lymph node | MDYL | MA01.Z |

| Melanoma-in-situ (grade 0) | MDBES | 2E63 |

| Keratolysis | MDIK | 1C44 |

| Talon noir (black heel)/hyperkeratosis hemorrhagica | FVTN | EH92.Y |

| Scabies | MDISC | 1G04 |

| Acne | MDYAC | ED80 |

| Myopia | MOJM | 9D00.0 |

| Hyperopia (hypermetropia) | MOJH | 9D00.1 |

| Astigmatism | MOJA | 9D00.2 |

| Pterygium | MOSP | 9A61.1 |

| Glaucoma | MOCG | 9C61 |

| Cataract | MOCC | 9B10 |

| Traumatic retinal hemorrhage | HORH | NA06.7 |

| Influenza virus | MPII | 1E30 |

| Respiratory syncytial virus | MPIRS | XN275 |

| Dengue fever | MXID | XN4CA |

| Malaria | MXIM | 1F4Z |

| Tuberculosis | MXITB | 1B1Z |

| Chikungunya | MXICV | 1D40 |

| Measles | MXIMS | 1F03 |

| Mumps | MXIMP | 1D80 |

| Rubella | MXIRV | 1F02 |

Abbreviations: ICD = International Classification of Diseases; OSIICS = Orchard Sports Injury and Illness Classification System.

4. Discussion

The injury and illness surveillance consensus process of the IOC in 2019 remains the ideal format in which to upgrade and update coding for sports injury and illness.6 It allows a large group of experts to use methodology that considers multiple opinions to inform the updated codes.

Nevertheless, disagreement with the outcome of such a process will always be present. Possibly, the most contentious change to a code in OSIICS 13 was the consensus recommendation that the Achilles tendon be considered part of the calf region rather than the ankle region. There are good arguments both ways (from an anatomical boundary perspective, the Achilles belongs in the ankle whereas from a functional unit perspective it belongs in the same region as the calf muscle group). Independent of this debate, it is a better process to make decisions using consensus methodology from many experts than unilaterally by a single expert (JWO). The biggest decision of the 2019 process was to align SMDCS and OSIICS so that the Achilles, for example, would be grouped in the same region in both systems and, therefore, would be tabulated in the calf/shin region in all sports medicine studies.

It was appropriate to include the identification of illness in the OSIICS title, but perhaps an oversight that some conditions that require coding are neither injuries nor illnesses (e.g., pregnancy). In this sense SMDCS is a more politically correct name because it doesn't suggest that injuries and illnesses are the only conditions worthy of coding. However, in contrast, the ICD has the least politically correct name (and perhaps can never be useful for sports medicine as long as it pertains primarily to disease).

One paper suggested reform of OSIICS (which has not been adopted) to include severity as part of the coding.44 There is no doubt it is important in any Athlete Management System (database) to record severity as well as diagnosis. However, assessment of severity is complex and, thus, probably inappropriate to be incorporated into a diagnostic coding system. First is the dilemma of whether severity should be judged on clinical grounds (dysfunction on clinical testing), radiological grounds (imaging appearance), missed playing or training time (duration of time loss, often not known at the time of initial coding), or level of performance limitation (functional severity). Beas-Jiménez et al.44 suggested a universal code for functional severity; however, functional limitations vary across the phase of rehabilitation and conflict with other ways of grading severity. For, say, muscle strains, there remains significant disagreement on the determination of severity. There are multiple non-conforming ways to grade muscle strains in the literature45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50 as well as published arguments that clinical parameters are preferable to imaging for assessing severity.51

Because OSIICS Version 15 was created by a smaller number of authors than were involved in the 2019–2020 IOC consensus panel process, the authors limited their changes to adding new codes that were considered important (particularly in the special areas listed in Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4). There were no major structural changes undertaken as we determined this would require a larger panel. Therefore, users of Versions 13 and 14 will find migration to Version 15 relatively straightforward; there are no missing codes, only additional ones. The major change to existing codes was the spelling out of abbreviations in full the first time they are used (i.e., no existing codes were changed from Version 14).

Many of the codes introduced in OSIICS Version 15 illustrate the difference in focus between the OSIICS and the ICD-11. Concussion has a single code in the ICD-11 (NA07.0) with a description of “loss or diminution of consciousness due to injury”, itself an inaccurate descriptor as concussion may occur without diminution of consciousness. The first recommended detail codes in the ICD-11 for concussion relate to whether pupils are reactive to light. In sports medicine presentations, pupil non-reaction is exceedingly rare, but concussion with no diminution of consciousness is very common. Motor incoordination (subsequent to head injury) without loss of consciousness is considered a definite concussion and an indication for compulsory removal according to the Consensus statement on concussion in sport,52 as well as in the rugby codes and in other sports. Because this sport-specific knowledge has led to change in legislation in certain sports, additional OSIICS codes have been created subsequently.

For some of the codes, it was challenging to determine whether they should be classified as injuries (with a body part first character) or as medical conditions (with a body-system base). For example, we concluded that pterygium was best classified as an ophthalmological condition rather than an eye injury and that Commotio Cordis was a cardiology condition rather than a chest injury, but we recognize and appreciate counter arguments.

Some infectious diseases have been given codes for the first time: For example malaria, which is a very rare diagnosis in athletes but included because it is one of the world's most common infectious diseases; there are over 30 different ICD-11 codes related to malaria.

5. Conclusion

Version 15 of OSIICS adds updated codes for mental health conditions in athletes, sports cardiology, concussion sub-types, infectious diseases, and skin and eye conditions. We encourage the translation of OSIICS into multiple languages over the course of 2024, and we aim to publish these versions in 2025 as OSIICS 15L.

Authors' contributions

JWO is the primary author of the OSIICS; MM particularly was involved in updating the mental health codes; JJO was involved in updating the sports cardiology codes; MM, ER, and KMC are sports epidemiology experts who provided oversight of the methods and process of adding code updates. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript, and agree with the order of presentation of the authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests, in particular that OSIICS is an open-access system that is not income generating.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Shanghai University of Sport.

Supplementary materials associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.jshs.2024.03.004.

Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Seward H, Orchard J, Hazard H, Collinson D. Football injuries in Australia at the elite level. Med J Aust. 1993;159:298–301. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1993.tb137863.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rae K, Britt H, Orchard J, Finch C. Classifying sports medicine diagnoses: A comparison of the International Classification of Diseases 10-australian modification (ICD-10-AM) and the Orchard Sports Injury Classification System (OSICS-8) Br J Sports Med. 2005;39:907–911. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2004.017517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ekstrand J, Bengtsson H, Waldén M, Davison M, Khan KM, Hägglund M. Hamstring injury rates have increased during recent seasons and now constitute 24% of all injuries in men's professional football: The UEFA Elite Club Injury Study from 2001/02 to 2021/22. Br J Sports Med. 2022;57:292–298. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2021-105407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sundaram V, Sundar V, Pearce AJ. Biomechanical characteristics of concussive and sub-concussive impacts in youth sports athletes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sports Sci. 2023;41:631–645. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2023.2231317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stannard J, Finch CF, Fortington LV. Improving musculoskeletal injury surveillance methods in Special Operation Forces: A Delphi consensus study. PLoS Glob Public Health. 2022;2 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgph.0000096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bahr R, Clarsen B, Derman W, et al. International Olympic Committee Consensus Statement: Methods for recording and reporting of epidemiological data on injury and illness in sports 2020 (including STROBE Extension for Sport Injury and Illness Surveillance—STROBE-SIIS) Br J Sports Med. 2020;54:372–389. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2019-101969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steffen K, Clarsen B, Gjelsvik H, et al. Illness and injury among Norwegian para athletes over five consecutive paralympic summer and winter games cycles: Prevailing high illness burden on the road from 2012 to 2020. Br J Sports Med. 2022;56:204–212. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2021-104489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levy IM. Formation and sense of the NAIRS athletic injury surveillance system. Am J Sports Med. 1988;16:S132–S133. doi: 10.1177/03635465880160s125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Orchard JW, Meeuwisse W, Derman W, et al. Sport Medicine Diagnostic Coding System (SMDCS) and the Orchard Sports Injury And Illness Classification System (OSIICS): Revised 2020 Consensus Versions. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54:397–401. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2019-101921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rae K, Orchard J. The Orchard Sports Injury Classification System (OSICS) Version 10. Clin J Sport Med. 2007;17:201–204. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0b013e318059b536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Orchard J, Genovesi F. Orchard Sports Injury and Illness Classification System (OSIICS) Version 14 and Italian translation. Br J Sports Med. 2022;22 doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2022-105828. bjsports-2022-105828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moore IS, Crossley KM, Bo K, et al. Female athlete health domains: A supplement to the International Olympic Committee consensus statement on methods for recording and reporting epidemiological data on injury and illness in sport. Br J Sports Med. 2023;57:1164–1174. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2022-106620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clarsen B, Pluim BM, Moreno-Pérez V, et al. Methods for epidemiological studies in competitive cycling: An extension of the IOC consensus statement on methods for recording and reporting of epidemiological data on injury and illness in sport 2020. Br J Sports Med. 2021;55:1262–1269. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2020-103906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Verhagen E, Clarsen B, Capel-Davies J, et al. Tennis-specific extension of the International Olympic Committee consensus statement: Methods for recording and reporting of epidemiological data on injury and illness in sport 2020. Br J Sports Med. 2021;55:9–13. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2020-102360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Waldén M, Mountjoy M, McCall A, et al. Football-specific extension of the IOC consensus statement: Methods for recording and reporting of epidemiological data on injury and illness in sport 2020. Br J Sports Med. 2023;57:1341–1350. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2022-106405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murray A, Junge A, Robinson PG, et al. International consensus statement: Methods for recording and reporting of epidemiological data on injuries and illnesses in golf. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54:1136–1141. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2020-102380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Post EG, Anderson T, Shilt JS, et al. Incidence of injury and illness among paediatric team USA athletes competing in the 2020 Tokyo and 2022 Beijing Olympic And Paralympic Games. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. 2023;9 doi: 10.1136/bmjsem-2023-001730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.METEOR. The orchard sports injury and illness classification system, Version 14.0. Available at: https://meteor.aihw.gov.au/content/787488. [accessed 10.03.2024]

- 19.Jones M. Injury and illness classification fields. Available at: https://smartabase.zendesk.com/hc/en-us/articles/15010022468884-Injury-and-Illness-Classification-Fields. [accessed 10.03.2024]

- 20.Orchard J. Orchard Sports Injury Classification System (OSICS) Sport Health. 1993;11:39–41. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Orchard J. In: Science and medicine in sport. Bloomfield J, Fricker P, Fitch K, editors. Blackwell; Melbourne: 1995. Orchard Sports Injury Classification System (OSICS) pp. 674–681. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Orchard J, Rae K, Brooks J, et al. Revision, uptake and coding issues related to the open access Orchard Sports Injury Classification System (OSICS) Versions 8, 9 and 10.1. Open Access J Sports Med. 2010;1:207–214. doi: 10.2147/OAJSM.S7715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hansen MG, Ross AG, Meyer T, Knold C, Meyers I, Peek K. Incidence, characteristics and cost of head, neck and dental injuries in non-professional football (soccer) using 3 years of sports injury insurance data. Dent Traumatol. 2023;39:542–554. doi: 10.1111/edt.12869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Helme M, Tee J, Emmonds S, Low C. The associations between unilateral leg strength, asymmetry and injury in sub-elite rugby league players. Phys Ther Sport. 2023;62:58–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ptsp.2023.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shanley E, Thigpen CA, Boes N, et al. Arm injury in youth baseball players: A 10-year cohort study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2023;32(Suppl.6):S106–S111. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2023.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Orchard JW, Inge P, Sims K, et al. Comparison of injury profiles between elite Australian male and female cricket players. J Sci Med Sport. 2023;26:19–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2022.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ross AG, McKay MJ, Pappas E, Bhimani N, Peek K. “Benched” the effect of the COVID-19 lockdown on injury incidence in sub-elite football in Australia: A retrospective population study using injury insurance records. Sci Med Footb. 2024;8:21–31. doi: 10.1080/24733938.2022.2143551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nicholas J, Weir G, Alderson JA, et al. Incidence, mechanisms, and characteristics of injuries in pole dancers: A prospective cohort study. Med Probl Perform Art. 2022;37:151–164. doi: 10.21091/mppa.2022.3022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ross AG, McKay MJ, Pappas E, Fortington L, Peek K. Direct and indirect costs associated with injury in sub-elite football in Australia: A population study using 3 years of sport insurance records. J Sci Med Sport. 2022;25:743–749. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2022.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buchholtz K, Barnes C, Burgess TL. Injury and illness incidence in 2017 Super Rugby Tournament: A surveillance study on a single South African team. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2022;17:648–657. doi: 10.26603/001c.35581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kennedy E, Bax J, Blanchard P, et al. Clients and conditions encountered by final year physiotherapy students in private practice. A retrospective analysis. Physiother Theory Pract. 2022;38:3027–3036. doi: 10.1080/09593985.2021.1975340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ngai ASH, Beasley I, Materne O, et al. Fractures in professional footballers: 7-years data from 106 team seasons in the Middle East. Biol Sport. 2023;40:1117–1124. doi: 10.5114/biolsport.2023.125588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mountjoy M, Junge A, Bindra A, et al. Surveillance of athlete mental health symptoms and disorders: A supplement to the International Olympic Committee's consensus statement on injury and illness surveillance. Br J Sports Med. 2023;57:1351–1360. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2022-106687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Falvey É C. Return to play recommendations for the elite adult player–2022 risk stratification. Available at: https://www.World.Rugby/the-game/player-welfare/medical/concussion/hia-protocol. [accessed 10.03.2024]

- 35.Davis GA, Makdissi M, Bloomfield P, et al. International consensus definitions of video signs of concussion in professional sports. Br J Sports Med. 2019;53:1264–1267. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2019-100628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Government UK. UK Concussion Guidelines for Non-Elite (Grassroots) Sport. Available at: https://sramedia.s3.amazonaws.com/media/documents/9ced1e1a-5d3b-4871-9209-bff4b2575b46.pdf. [accessed 10.03.2024]

- 37.Baggish AL, Battle RW, Beckerman JG, et al. Sports cardiology: Core curriculum for providing cardiovascular care to competitive athletes and highly active people. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:1902–1918. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.08.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moulson N, Petek BJ, Ackerman MJ, et al. Rationale and design of the ORCCA (Outcomes Registry For Cardiac Conditions in Athletes) study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2023;12 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.122.029052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Malhotra A, Dhutia H, Finocchiaro G, et al. Outcomes of cardiac screening in adolescent soccer players. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:524–534. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1714719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Adams BB. Dermatologic disorders of the athlete. Sports Med. 2002;32:309–321. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200232050-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.De Luca JF, Adams BB, Yosipovitch G. Skin manifestations of athletes competing in the Summer Olympics: What a sports medicine physician should know. Sports Med. 2012;42:399–413. doi: 10.2165/11599050-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ashraf G, Arslan J, Crock C, Chakrabarti R. Sports-related ocular injuries at a tertiary eye hospital in Australia: A 5-year retrospective descriptive study. Emerg Med Australas. 2022;34:794–800. doi: 10.1111/1742-6723.13982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Patel V, Pakravan P, Mehra D, Watane A, Yannuzzi NA, Sridhar J. Trends in sports-related ocular trauma in United States emergency departments from 2010 to 2019: Multi-center cross-sectional study. Semin Ophthalmol. 2023;38:333–337. doi: 10.1080/08820538.2022.2107400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Beas-Jiménez JD, Garrigosa AL, Cuevas PD, et al. Translation into Spanish and proposal to modify the Orchard Sports Injury Classification System (OSICS) Version 12. Orthop J Sports Med. 2021;9 doi: 10.1177/2325967121993814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mueller-Wohlfahrt HW, Haensel L, Mithoefer K, et al. Terminology and classification of muscle injuries in sport: The Munich consensus statement. Br J Sports Med. 2013;47:342–350. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2012-091448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Valle X, Alentorn-Geli E, Tol JL, et al. Muscle injuries in sports: A new evidence-informed and expert consensus-based classification with clinical application. Sports Med. 2017;47:1241–1253. doi: 10.1007/s40279-016-0647-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chan O, Del Buono A, Best TM, Maffulli N. Acute muscle strain injuries: A proposed new classification system. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012;20:2356–2362. doi: 10.1007/s00167-012-2118-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pollock N, James SL, Lee JC, Chakraverty R. British athletics muscle injury classification: A new grading system. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48:1347–1351. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2013-093302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Paton BM, Court N, Giakoumis M, et al. London international consensus and Delphi study on hamstring injuries part 1: Classification. Br J Sports Med. 2023;57:254–265. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2021-105371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wangensteen A, Guermazi A, Tol JL, et al. New MRI muscle classification systems and associations with return to sport after acute hamstring injuries: A prospective study. Eur Radiol. 2018;28:3532–3541. doi: 10.1007/s00330-017-5125-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reurink G, Whiteley R, Tol JL. Hamstring injuries and predicting return to play: “Bye-bye MRI?”. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49:1162–1163. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2015-094771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Patricios JS, Schneider KJ, Dvorak J, et al. Consensus statement on concussion in sport: The 6th International Conference on Concussion in Sport–Amsterdam, October 2022. Br J Sports Med. 2023;57:695–711. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2023-106898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.