Learning objectives.

By reading this article, you will be able to:

-

•

Recognise the manifestations and impact of bias, prejudice and racism in healthcare.

-

•

Explain the neuropsychology of stereotypes, prejudice and bias.

-

•

Implement best practices for designing skills-based training curricula to address bias and microaggressions.

-

•

Respond to organisational mandates and apply recommended practices, whilst being prepared for potential pitfalls and challenges of such initiatives.

Key points.

-

•

Bias, prejudice and racism are global phenomena that affect health outcomes and health professionals.

-

•

Bias has cognitive, affective and behavioural components.

-

•

Training aims to raise awareness, explore others' perspectives and teach bias reduction strategies.

-

•

The design of a bias training programme should use needs assessment, established conceptual frameworks and rigorous assessment.

-

•

Longitudinal skills-based curricula are probably most effective for mitigating the effects of sustained bias.

Bias in healthcare is pervasive worldwide, despite increasing awareness and an explicit commitment to its elimination.1 Patterns of bias manifest differently according to the unique historical, economic and cultural contexts of different regions. For example, because of the legacy of chattel slavery in the United States, bias towards race remains prominent. However, bias may also be based on gender, directed toward indigenous populations, immigrants, based on religious background, sexual identity/sexual orientation and obesity.2 Other common manifestations of bias are associated with refugee status, disability and older age.2 The intersection of marginalised identities may further compound bias. For example, Black women physicians may experience bias to a greater extent than their Black male counterparts.3 Much of the information in this article is drawn from the North American literature.

Recent reports indicate that anaesthesia providers may contribute to race-based health disparities. A retrospective cohort study reviewed the perioperative use of antiemetics in >5 million anaesthetics in the USA between 2004 and 2018.4 The authors found that significantly fewer perioperative antiemetics were given to Black compared with White patients.4 Similarly, a retrospective cross-sectional study across New York State hospitals between 1998 and 2016 reviewed the management of almost 9000 patients with postdural puncture headache.5 There was significantly lower and delayed use of epidural blood patch among racial and ethnic minority patients compared with White patients.5 In England, Bamber and colleagues analysed >6 million childbirth episodes (2011–2021) and found a significantly higher likelihood of general anaesthesia for elective Caesarean birth among patients with Caribbean or African origin compared with White British patients.6 In addition, those of Bangladeshi or Pakistani origin were less likely to receive neuraxial anaesthesia compared with British White patients.6

Bias towards women regarding gender in the diagnosis and management of heart disease and pain management is well documented.7 There is a persistent gender-based pay gap and a lack of advancement of women with respect to promotions and leadership in medicine.8 The unique perioperative health needs of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transsexual and queer/questioning (LGBTQ+) individuals are often overlooked and there are significant inequities in health outcomes. Furthermore, medical curricula in North America have been criticised as not being designed to prepare physicians to deliver culturally appropriate care and meet the unique needs of this patient population.9 Finally, some religious minorities report significant discrimination in their interaction with healthcare providers, and as health professionals.10

Pulse oximeters have been found to overestimate oxygen saturation among patients with dark skin tones, leading to possible worse clinical outcomes because of higher rates of occult hypoxaemia.11 It is thought that insufficient inclusion of individuals with dark skin tones in device validation studies may have caused this miscalibration.

Algorithmic discrimination associated with the use of artificial intelligence tools is another increasing concern. The algorithms, often trained on data that lack diversity and contain built-in bias and systematic errors, potentially lead to harms such as delayed diagnosis, medical interventions and poorer healthcare outcomes for individuals from marginalised groups.12

With the recognition that bias and structural racism contribute to perpetuating inequities in health outcomes, accreditation bodies and professional organisations worldwide have instituted policies for mandatory training in recognising and responding to incidents of bias and prejudice, whether directed toward patients, or toward healthcare providers.13,14

Neuropsychology of stereotypes, prejudice and bias

Bias has three psychological components: cognitive (stereotypes), affective (prejudice) and behavioural (discrimination).2 Implicit bias, a term coined in 1995 by psychologists Greenwald and Banaji, encompasses both prejudicial attitudes and stereotypical beliefs, which are spontaneously activated and can ultimately lead to discriminatory behaviours.2,15

Stereotypes, described as the cognitive building blocks of our mental schema, serve as ‘energy-saving’ shortcuts to allow expedient high-level categorisation of items such as ‘friend or foe’ when encountering a stranger.16 In the social context, stereotypes involve generalised descriptions of members of a group, often acquired early in life and shared by a group or culture.16 Accordingly, they are often associated with behavioural expectations, and may be assigned arbitrary characteristics.16 Whether favourable or unfavourable, stereotypes function to rationalise the conduct toward members of a group.16 They often lead to prejudicial behaviour when the judgment of an individual's abilities is based on their group identity, resulting in favouritism towards members of groups with whom they psychologically identify (ingroup), and bias towards members of group with whom they do not psychologically identify (outgroup).16 Discrimination, defined as denying ‘individuals or groups equality of treatment they may wish’ may be exerted at the interpersonal level between two or more people, but may also occur at the institutional level by becoming embedded in policies and practices that are informed implicitly or explicitly by stereotypes.17 Furthermore, the insertion of race into diagnostic algorithms and practice guidelines has the potential to cause harm, as this social construct has no biological meaning.18

The neural basis of prejudice involves networks between brain structures involved in emotion and motivation, such as the amygdala (fear, threat perception), insula (somatosensory states/visceral response, empathy), striatum and areas in the orbital and ventromedial frontal cortices (monitoring social cues).1 The amygdala rapidly processes social category cues, such as socially defined race, as being a reward or possible threat.1 The insula mediates the physical and emotional response towards members of social outgroups or ingroups.1 The orbital frontal cortex is involved with emotionally driven judgements of members of social outgroups, the latter processes being associated with a reduced activity in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, the region of the brain concerned with empathy and the ability to understand one's own mental state.1 In contrast, stereotyping, believed to have a cognitive component, involves cortical structures such as the temporal lobe and inferior frontal gyrus which support semantic and objective memory, and retrieval and conceptual activation. Both networks interact and impact cognition and behaviour.1 The lateral and medial prefrontal cortex also appear to play a role in regulating emotion and social behavioural responses.1

The probable biological basis of prejudice and stereotyping might mean that implicit bias cannot be eradicated completely from human behaviours, particularly in cultures that continually reinforce them.1 Accordingly, intentional control of behaviour may be more effective than attempting to extinguish bias, and behaviour changes may then become habitual.2

Microaggressions and their impact

The manifestations of bias can be overt, but may also be indirect and even unintentional, sometimes referred to as ‘microaggressions’. The term microaggressions was introduced in the 1970s by Chester Pierce to describe the “subtle, stunning, often automatic, and non-verbal exchanges which are put downs” of Black people by non-Black people.19 The concept of microaggressions was reintroduced decades later by Derald Wing Sue and colleagues who defined them as ‘brief commonplace daily verbal, behavioural, and environmental indignities, whether intentional or unintentional, that communicate hostile, derogatory, or negative racial slights and insults to the target person or group’.20

Microaggressions have been further categorised as microassaults (discriminatory behaviour or speech, e.g. saying “That's so gay”), microinsults (insensitive comments, e.g. in a Western country, telling an Asian individual that they speak English well), or microinvalidations (dismissive and exclusionary practices, e.g. telling a woman that she is being too sensitive).21

In contrast to overt discriminatory behaviour, implicit bias is difficult to identify, quantify and rectify because of its insidious and nebulous nature.20 Accordingly, assessment of the impact of bias should rely on the perceptions of the target of bias rather than on the instigator's intent.20 The cumulative burden of these occurrences, which are often minimised by others, shapes interpersonal relations, and has negative repercussions on the psychological, emotional, and somatic health of targets.19,20

Microaggressions and bias are associated with disparities in health outcomes, and may have adverse effects on physical health from the physiological consequences of chronic stress or ‘allostatic load’.22 They may also affect the quality of life, job satisfaction, and performance of healthcare professionals.21,23 Providers should be trained to recognise and manage experienced or witnessed bias directed to either patients or peers. One large survey of surgical residents in the United States revealed that those who experienced racism and other forms of discrimination were more likely to describe symptoms consistent with burnout and to have suicidal thoughts.23 Healthcare providers may experience discrimination from patients and their families, peers, or supervisors, and may be reluctant to report incidents of racism or bias because of the desire to avoid damaging relationships, fear of retaliation, lack of knowledge about reporting mechanisms, or lack of trust in their institution's ability to respond effectively. The hierarchical nature of medicine may contribute to hesitation to report superiors. In such cases, outside support may need to be sought.23,24

Approaches to managing bias

Given that stereotypes are ingrained and automatic, their modulation requires deliberate and consistent efforts.16,20 Several ‘debiasing strategies’ addressing various forms of bias have been described both in the field and in the laboratory (Table 1).25,26 In addition, reducing stereotype activation has been attempted on volunteers through interventions such as mood alteration using music, or giving drugs such as propranolol.25 Overall, the success of any intervention has been limited; even modest reductions in measured bias are short-lived with no proved effect on behaviour.26

Table 1.

Examples of ‘debiasing’ and ‘habit-breaking’ interventions. Taken from references.2, 25, 26, 44, 46, 47

| Strategy/approach | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Contact | The ‘contact hypothesis’ holds that repeated positive interactions with individuals with a different social identity (e.g. race, gender and sexual orientation) is linked with a reduction in stereotyping, prejudice and discrimination. | Study of simulated workplace contact between white racially prejudiced adults who believed that they were hired to work on a railroad company management task with a Black and White confederate led to more positive attitudes in the prejudiced individuals of their Black ‘coworkers’. |

| Perspective taking | Actively contemplate the point of view and psychological experiences of others. | Write an essay from the perspective of an older adult. |

| Individuating | Evaluate and distinguish individuals based on personal characteristics as opposed to those associated with that group. | Avoid stereotypical inferences of people of other races by gathering more information about background, taste, hobbies and family. |

| Stereotype replacement | Replace personal stereotypical responses for non-stereotypical response. | Recognise a personal response as stereotypical, reflect on the reason and consider how the response can be avoided in future. |

| Counterstereotypical imaging | Imagine people who counter commonly-held stereotypes. View photographs of individuals from marginalised identities who do not conform to stereotypes. |

Expose participants to images of admired Black and disliked White individuals. Display images or symbols from groups with marginalised identities in common spaces. |

In contrast, the recommended approaches to managing implicit bias fall in one of three categories: raising awareness of bias and prejudice, exploring perspectives and providing bias reduction strategies (Table 2).27

Table 2.

Strategies for recognising and managing bias.

| Strategy | Intervention | Goals | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Raising awareness | Provocative engagement triggers | Exposing group biases |

|

| Implicit association test | Exposing own biases and implicit associations |

|

|

| Facilitated reflection | Reflection on biases in self and in systems |

|

|

| Exploring perspectives | Cultural humility | Explore alternate perspectives | |

| Teaching bias reduction | Simulation | Develop skills to mitigate bias; engage in self-reflection to uncover bias |

|

A limited number of skills-based curricula in healthcare have been reported, with varied content and delivery methods.14 Instructional delivery may be in-person or web-based, delivered in formats ranging from lectures, to interactive workshops, or simulation-based education. These can be one-off instructions or longitudinal courses, some occurring over a period of up to several months.14

Raising awareness

Raising awareness of personal bias and prevailing prejudice is considered an important necessary, but not sufficient step.28 These interventions are designed to bring the individual's existing bias to the surface by using ‘provocative engagement triggers’ such as discussions of scenarios where biases are unexpectedly exposed or using the implicit association test (https://implicit.harvard.edu/implicit/takeatest.html), a widely used online simultaneous classification task for which response latency is used as a proxy for implicit associations between categories. The construct validity and inability to predict behaviour has been criticised. Other strategies for raising awareness include facilitated reflection and discussion exercises where participants are invited to reflect on structural inequities and their impact, and the influence of implicit bias on policymaking.

Exploring perspectives

Described like ‘death by a thousand paper cuts’, bias and discrimination can erode the psychological, emotional and cognitive health of their targets.21 Because of their subtle nature, these instances are readily dismissed as inadvertent/accidental, and therefore not rising to the level that requires intervention.20 Strategies that use role playing in conflict management, followed by structured debriefs, encourage learners to adopt a different perspective and explore alternative possibilities.14 These exercises are consistent with the concept of cultural humility, defined as a “commitment and active engagement in a lifelong practice of self-evaluation and self-critique within the context of the patient-provider (or health professional) relationship through patient-oriented interviewing and care”.29 Culture encompasses ‘the customary beliefs, social norms, and material traits of a racial, religious, or social group’ and influences individuals' interpretation of information and, in the provider–patient context, the development of shared objectives.30 Culture can affect the expression of symptoms such as pain, and care choices.21 In today's multicultural societies, providers must be equipped to provide cross-cultural care.

Bias reduction strategies

Strategies to effect bias reduction have the dual purpose of identifying and labelling biased behaviours, and to provide targets and witnesses with skills to navigate those situations. This may be best accomplished through simulation or role-playing exercises.31

Simulation has been used to address issues related to equity, inclusion and advocacy by teaching behavioural skills such as communication and history-taking.31 Most reports describe using standardised patients or role play; none used high fidelity manikins or virtual reality.31 A few simulation experiences were conducted as longitudinal curricula, but the majority were one-time opportunities. Assessment of session effectiveness relied on self-report, self-assessment, or objective structured clinical examinations; changes in behaviour and longitudinal outcomes were not assessed.31 Best practices for simulation-based approaches are summarised in Supplementary Appendix A.

Workshops designed to provide skills for witnesses of discriminatory everyday experiences to intervene allows the bystander to become an ‘upstander’, which refers to a form of allyship.32 Allyship is ‘a supportive association with another group, specifically members of marginalised or mistreated groups to which one does not belong’.33 Depending on the context, allyship may manifest through direct or indirect strategies, and may be in the moment or delayed (Fig. 1).21 To ensure a constructive response to microaggressions and discrimination, the focus should remain on the behaviour and not on the individual perpetrator.24 After committing a microaggression oneself, recommendations include acknowledging the mistake, accepting feedback and thanking the recipient for sharing their experience.20

`Fig 1.

Upstander responses to witnessed microaggression. Adapted from Ehie and colleagues.21.

Workshops can be designed as interactive, collaborative sessions, using the concept of forum theatre (FT).34 Forum theatre is based on the work of Paul Freire in the early 1970s, describing the emancipatory power of education achieved through the development of ‘critical consciousness’.35 These concepts inspired Augusto Boal to create the ‘Theatre of the oppressed’, a set of theatrical techniques that enable the audience to take part in recognising a situation of oppression, and transforming the reality through collaborative rewriting of the script.36 Forum theatre is designed with a set of enacted scripts or vignettes where an instigator engages in bias and discrimination against a target in the presence of a bystander. The audience is then asked to reflect on the action, identify the bias and discrimination and develop alternate paths to approach the situation and resolve the conflict. Forum theatre can be conducted in person or virtually. The power of FT resides in allowing participants to engage in uncomfortable conversations in a safe and simulated environment, to explore different perspectives and to witness bias and discrimination regardless of past personal experiences, and to generate constructive strategies for responding to and managing bias.34 Forum theatre can help participants recognise incidents of bias by others or by themselves, and develop the confidence to intervene. In one example, these self-reported trends were sustained 6 months after workshop attendance.37

Curricula designed for anaesthetists should be tailored to incorporate realistic clinical scenarios, such as pain assessment in a patient with low proficiency in English. The sessions should provoke reflection on individual and system biases and teach practical skills, such as the effective use of interpreters.

Limitations of training and barriers to success

There is a paucity of evidence to support the effectiveness of strategies proposed to reduce bias, stereotype and prejudice.2 Challenges include defining the desirable outcomes, designing relevant assessment methods, implementing processes and interventions and ignoring recognised pitfalls.

Lack of standardised methods of assessment increases the difficulty of comparing interventions or confirming their effectiveness. Most measures of effectiveness are based on participants' self-reports of increased awareness of implicit bias.14 Others compare pre- and post-intervention scores on the implicit association test. No evidence exists for changes in behaviour, or improvement in health outcomes or patient experiences.26 Furthermore, training effects can decay over time. Studies are warranted to assess the sustained effectiveness of training with more objective and patient-centred indicators.2,14

The implementation of curricula to manage bias is challenged by the difficulty of recruiting faculty educators.28 This may result from a misperception of lack of direct relevance to patient care, and concurrent pressure to focus on medically-centred curricular content. In addition, facilitation approaches are not standardised and there are few publications of skills-based curricula.14 Likewise, because of time pressures, interventions are often brief and not well incorporated into standing curricula.

Interventions that do not provide practical skills and strategies may have unintentional harmful consequences leading to avoidance of patients from marginalised groups, withdrawal, by spending less time with patients, or overcompensation and sounding insincere.2 Interestingly, research has shown that simply instructing participants to suppress stereotypes can have the opposite effect.25

The challenges to the success of training interventions are first, it is unlikely that a brief training will be sufficient to counter existing world views, constructed over a lifetime from lived experiences and media exposure. Second, counteracting apathy from majority or socially privileged groups is challenging. Despite egalitarian norms, research has shown that individuals tend not to be distressed by witnessing outgroup racism.38 Third, learners may reject training when it generates feelings of cognitive dissonance and discomfort, from being confronted by their behaviours that are counter to their espoused beliefs.39 Fourth, encounters in the clinical learning environments can perpetuate or worsen existing biases. Lastly, ‘moral licensing bias’ may result when participants perceive their training credentials to protect their actions from appearing biased, thereby paradoxically increasing their likelihood of engaging in prejudicial or racist behaviours.40

Key factors to consider when implementing bias training programmes

Addressing bias is both a compliance issue and a moral imperative for anaesthetists.25 The goals of training are to increase awareness of workplace diversity concerns and to promote a positive culture and healthy interactions between co-workers and with patients.40

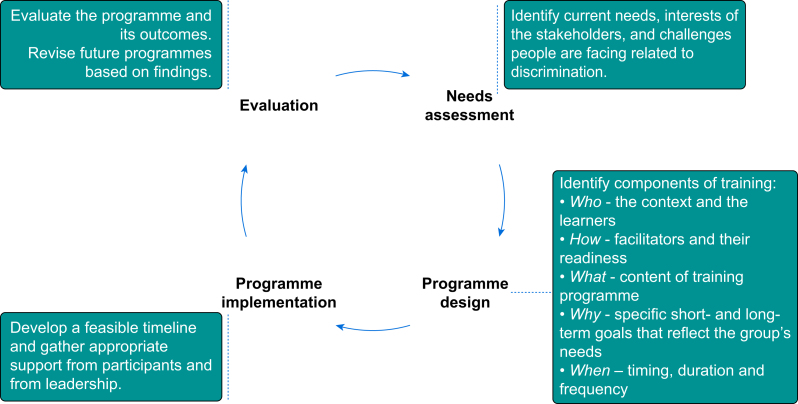

A structured and stepwise approach, designing programmes that are informed by a clear needs assessment, anchored in desired outcomes, and use of rigorous assessment methods is ideal (Fig. 2).2 Programmatic needs (the gap between the current state and desired objectives) will vary between programmes and over time. Using established conceptual frameworks ensures clarity in design and gathers support of the various stakeholders (Table 3).

Fig 2.

Stepwise approach to designing bias training programmes.

Table 3.

Concept mapping for programme design.

| Context | Facilitators | Content and format | Outcomes and evaluations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perform a needs assessment | Training facilitators in delivery and moderation of sensitive topics | Consider inclusion of community member in content development | Define desirable outcomes as short-term and long-term; aim for patient-centred outcomes |

| Identify target audience and characteristics | Training in pre- and debrief | Provide pre-learning material to include background, theory, rationale | Evaluations should move beyond feasibility and participant satisfaction |

| Obtain buy-in from stakeholders | Consider engaging expert facilitators | Debriefing allows self-reflection and managing difficult moments | Participants surveys can explore immediate satisfaction and engagement, and perceived learning |

| Recognise situational challenges to implementation and adjust accordingly | Provide feedback to facilitators frequently based on observations or participants' comments | Provide skills training and actionable tools | Patient surveys when feasible can identify changes in behaviours and improved outcomes |

Context and learners

Learners' characteristics should be carefully considered so that scenarios are relevant to the audience. Thoughtful selection of participants should be conducted. Mid-level leaders are particularly important to champion the process, lead by example, provide mentoring and be engaged with social accountability.40 Voluntary training programmes tend to attract only those individuals who are already engaged in the efforts. However, mandatory training may generate resentment and be poorly received. Communications about the purpose of the training should be clear to avoid the perceptions of pro forma activity. Training should not be provided in isolation but should be implemented in conjunction with process changes within the organisation. Best practices for conducting bias training are summarised in Supplementary Appendix B.

Facilitators

Training of facilitators is important because of the sensitive nature of the topics, the reluctance of participants to engage openly in self-reflection, the risk of tokenism or reinforcing racial and ethnic stereotypes and of reductive perspectives.30 Facilitators must set a tone of psychological safety for participants. Programmes should furthermore engage with existing resources and experts such as community health workers, language-concordant educational materials for patients and access to interpreters, including for the hearing impaired.

Content and format

Whenever possible, programmes for recognising and managing bias should be integrated into established anaesthetic trainee and departmental curricula. This ensures a holistic approach to the topics that are then accepted as central to the mission of a group. An ‘information deficit model’, that ignores that course content may be discordant with participants' experiences, should be avoided.41 Practical strategies for changing behaviour should be provided along with predictable follow-up.

Poorly designed programmes can lead to confusion, resentment, or inadvertent activation of stereotypes and are unlikely to prompt behaviour change.40 Backlash from poorly received programmes can include heightened animosity related to difference—individuals from majority/socially privileged groups may feel vilified, ‘needing to walk on eggshells’, or affirmed in their beliefs that people with marginalised identities are too sensitive.40

Sustained effects are unlikely after a single session or intervention.2 A grand rounds format may be used to introduce the topic and reach a wider audience.42 A longitudinal, ongoing process, with multiple sessions with varying formats is recommended.25

No standardised curricula exist as curricula tend to be tailored for individual institutions.30 However, it is recommended that content be patient-centred and tailored toward patients' characteristics and local community requirements. As part of the process, participants should be called upon to engage in self-critique and reflect on their identity, to acknowledge the power imbalance of the patient–provider relationship and to engage in active listening and shared decision-making.43 In addition to raising awareness of bias, successful programmes should aim to provide concrete, evidence-based ‘habit-breaking’ strategies, using existing or novel frameworks.2,25,44 More theory-driven strategies, the effectiveness of which should be tested with healthcare providers, followed by studies of the impact on practice and the wider community are warranted.

Most health disparities literature focuses on implicit prejudice (affective) and not stereotyping (cognitive). The interrelated concepts contribute to health disparities in different ways (i.e. communication vs treatment, respectively), so experts recommend that the intent of the training should be clear.45 For example, patients belonging to marginalised groups perceive inferior patient–provider communication with healthcare providers documented as having implicit prejudice; physicians who believe the stereotype that Black individuals are less compliant, may make different treatment decisions.45 Given how difficult bias is to eliminate, some experts advocate for a greater focus on skills for improving communication behaviours—body language, eye contact and body distance—and paraverbal behaviours (tone, pitch and volume of speech) and content of speech, as this may be more achievable and become habitual.2

Evaluation

Evaluation of the success of interventions can examine feasibility, participants' satisfaction with the programme, or their perceived self-assessment of learning. Provider behaviour changes are challenging to evaluate. Patient satisfaction surveys may be informative and can reflect changes in practice. Surveys may ask about planned behaviour change, but actual behaviour change has not been studied. Creating a logic model to conceptualise interventions and assessments, and desired/expected outcomes at the individual, organisational and societal level, may be valuable for the design and evaluation of a programme.27

Conclusions

Bias and prejudice continue to be pervasive in healthcare, affecting both providers and their patients. Despite the widespread availability of educational materials and implementation of training interventions, sustainable change is difficult to achieve and to assess. To accomplish the goal of professional and safe workspaces and to eliminate disparities in healthcare, there is a pressing need for the development of innovative skills-based instruction, and objective, validated outcome metrics to assess the effectiveness of such strategies in changing behaviours meaningfully.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

MCQs

The associated MCQs (to support CME/CPD activity) will be accessible at www.bjaed.org/cme/home by subscribers to BJA Education.

Biographies

Allison Lee MD MS is a professor of clinical anesthesiology and critical care at the Perelman School of Medicine within the University of Pennsylvania. She is the departmental vice chair for Diversity, Equity and Inclusion, and the block chief for obstetric anesthesia.

Maya Hastie MD Ed D is a professor of anesthesiology at Columbia University Irving Medical Centre, in the department of anesthesiology at Columbia University. She is the departmental vice chair for education and a member of the division of adult cardiothoracic anesthesia.

Matrix codes: 1F04, 2H01, 3J02

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjae.2024.03.006.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Amodio D.M. The neuroscience of prejudice and stereotyping. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2014;15:670–682. doi: 10.1038/nrn3800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hagiwara N., Kron F.W., Scerbo M.W., Watson G.S. A call for grounding implicit bias training in clinical and translational frameworks. Lancet. 2020;395:1457–1460. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30846-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soussi S., Mehta S., Lorello G.R. Equity, diversity, and inclusion in anaesthesia and critical care medicine: consider the various aspects of diversity. Br J Anaesth. 2023;131:e135–e136. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2023.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.White R.S., Andreae M.H., Lui B., et al. Antiemetic administration and its association with race: a retrospective cohort study. Anesthesiology. 2023;138:587–601. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000004549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee A., Guglielminotti J., Janvier A.S., Li G., Landau R. Racial and ethnic disparities in the management of postdural puncture headache with epidural blood patch for obstetric patients in New York State. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.8520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bamber J.H., Goldacre R., Lucas D.N., Quasim S., Knight M. A national cohort study to investigate the association between ethnicity and the provision of care in obstetric anaesthesia in England between 2011 and 2021. Anaesthesia. 2023;78:820–829. doi: 10.1111/anae.15987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim I., Field T.S., Wan D., Humphries K., Sedlak T. Sex and gender bias as a mechanistic determinant of cardiovascular disease outcomes. Can J Cardiol. 2022;38:1865–1880. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2022.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hastie M.J., Lee A., Siddiqui S., Oakes D., Wong C.A. Misconceptions about women in leadership in academic medicine. Can J Anaesth. 2023;70:1019–1025. doi: 10.1007/s12630-023-02458-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ejiogu N.I. LGBTQ+ health and anaesthesia for obstetric and gynaecological procedures. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2022;35:292–298. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0000000000001134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Padela A.I., Azam L., Murrar S., Baqai B. Muslim American physicians’ experiences with, and views on, religious discrimination and accommodation in academic medicine. Health Serv Res. 2023;58:733–743. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.14146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jamali H., Castillo L.T., Morgan C.C., et al. Racial disparity in oxygen saturation measurements by pulse oximetry: evidence and implications. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2022;19:1951–1964. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202203-270CME. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoffman S. The emerging hazard of AI-related healthcare discrimination. Hastings Cent Rep. 2021;51:8–9. doi: 10.1002/hast.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pennington C.R., Bliss E., Airey A., Bancroft M., Pryce-Miller M. A mixed-methods evaluation of unconscious racial bias training for NHS senior practitioners to improve the experiences of racially minoritised students. BMJ Open. 2023;13 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-068819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gonzalez C.M., Onumah C.M., Walker S.A., Karp E., Schwartz R., Lypson M.L. Implicit bias instruction across disciplines related to the social determinants of health: a scoping review. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2023;28:541–587. doi: 10.1007/s10459-022-10168-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greenwald A.G., Banaji M.R. Implicit social cognition: attitudes, self-esteem, and stereotypes. Psychol Rev. 1995;102:4–27. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.102.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Augoustinos M., Walker I. The construction of stereotypes within social psychology – from social cognition to ideology. Theor Psychol. 1998;8:629–652. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Allport G.W. Addison-Wesley; Cambridge, Mass: 1954. The Nature of Prejudice. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vyas D.A., Eisenstein L.G., Jones D.S. Hidden in plain sight — reconsidering the use of race correction in clinical algorithms. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:874–882. doi: 10.1056/NEJMms2004740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pierce C.M., Carew J.V., Pierce-Gonzalez D., Wills D. An experiment in racism: TV commercials. Educ Urban Soc. 1977;10:61–87. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sue D.W., Capodilupo C.M., Torino G.C., et al. Racial microaggressions in everyday life – Implications for clinical practice. Am Psychol. 2007;62:271–286. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.4.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ehie O., Muse I., Hill L., Bastien A. Professionalism: microaggression in the healthcare setting. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2021;34:131–136. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0000000000000966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guidi J., Lucente M., Sonino N., Fava G.A. Allostatic load and its impact on health: a systematic review. Psychother Psychosom. 2021;90:11–27. doi: 10.1159/000510696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hu Y.Y., Ellis R.J., Hewitt D.B., et al. Discrimination, abuse, harassment, and burnout in surgical residency training. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1741–1752. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1903759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hastie M.J., Jalbout T., Ott Q., Hopf H.W., Cevasco M., Hastie J. Disruptive behavior in medicine: sources, impact, and management. Anesth Analg. 2020;131:1943–1949. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000005218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paluck E.L., Green D.P. Prejudice reduction: what works? A review and assessment of research and practice. Annu Rev Psychol. 2009;60:339–367. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Forscher P.S., Lai C.K., Axt J.R., et al. A meta-analysis of procedures to change implicit measures. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2019;117:522–559. doi: 10.1037/pspa0000160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sukhera J., Watling C. A framework for integrating implicit bias recognition into health professions education. Acad Med. 2018;93:35–40. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gonzalez C.M., Lypson M.L., Sukhera J. Twelve tips for teaching implicit bias recognition and management. Med Teach. 2021;43:1368–1373. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2021.1879378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tervalon M., Murray-García J. Cultural humility versus cultural competence: a critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 1998;9:117–125. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trinh N.H., Jahan A.B., Chen J.A. Moving from cultural competence to cultural humility in psychiatric education. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2021;44:149–157. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2020.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Daya S., Illangasekare T., Tahir P., et al. Using simulation to teach learners in healthcare behavioral skills related to diversity, equity, and inclusion: a scoping review. Simul Healthc. 2023;18:312–320. doi: 10.1097/SIH.0000000000000690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.York M., Langford K., Davidson M., et al. Becoming active bystanders and advocates: teaching medical students to respond to bias in the clinical setting. MedEdPORTAL. 2021;17 doi: 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.11175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martinez S., Araj J., Reid S., et al. Allyship in residency: an introductory module on medical allyship for graduate medical trainees. MedEdPORTAL. 2021;17 doi: 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.11200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rizk N., Jones S., Shaw M.H., Morgan A. Using forum theater as a teaching tool to combat patient bias directed toward healthcare professionals. MedEdPORTAL. 2020;16 doi: 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.11022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Freire P. 30th anniversary Edn. Continuum; New York: 2000. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boal A. Pluto Press; New Wing, Somerset House, Strand, London, WC2R 1LA: 2000. Theater of the Oppressed. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Patnaik R., Mueller D., Dyurich A., et al. Forum theatre to address peer-to-peer mistreatment in general surgery residency. J Surg Educ. 2023;80:563–571. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2022.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Karmali F., Kawakami K., Page-Gould E. He said what? Physiological and cognitive responses to imagining and witnessing outgroup racism. J Exp Psychol Gen. 2017;146:1073–1085. doi: 10.1037/xge0000304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sukhera J., Watling C.J., Gonzalez C.M. Implicit bias in health professions: from recognition to transformation. Acad Med. 2020;95:717–723. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dobbin F., Kalev A. Why doesn’t diversity training work? The challenge for industry and academia. Anthropol Now. 2018;10:48–55. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cox W.T.L. Developing scientifically validated bias and diversity trainings that work: empowering agents of change to reduce bias, create inclusion, and promote equity. Manag Decis. 2023;61:1038–1061. doi: 10.1108/md-06-2021-0839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rodriguez N., Kintzer E., List J., et al. Implicit bias recognition and management: tailored instruction for faculty. J Natl Med Assoc. 2021;113:566–575. doi: 10.1016/j.jnma.2021.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chang E.S., Simon M., Dong X. Integrating cultural humility into healthcare professional education and training. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2012;17:269–278. doi: 10.1007/s10459-010-9264-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Forscher P.S., Mitamura C., Dix E.L., Cox W.T.L., Devine P.G. Breaking the prejudice habit: mechanisms, timecourse, and longevity. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2017;72:133–146. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2017.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maina I.W., Belton T.D., Ginzberg S., Singh A., Johnson T.J. A decade of studying implicit racial/ethnic bias in healthcare providers using the implicit association test. Soc Sci Med. 2018;199:219–229. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.estcott CA, Blair IV, Stone J. Examining the Presence, Consequences, and Reduction of Implicit Bias in Health Care: A Narrative Review. Group Process Intergroup Relat. 2016;19(4):528–542. doi: 10.1177/1368430216642029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dasgupta N, Greenwald AG. On the malleability of automatic attitudes: combating automatic prejudice with images of admired and disliked individuals. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2001;81(5):800–801. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.81.5.800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.