Accountability is at the heart of the concept of clinical governance. Not only must health professionals strive to improve the quality of care, they must also be able to show that they are doing so.

The notion of accountability is not new—clinicians have long been accountable to their professional regulatory bodies. However, recent scandals about dangerous practice by doctors have damaged confidence in the current system of peer-led self regulation and raised concerns about the limited accountability of doctors in particular.1,2 The new requirement for primary care clinicians to be answerable to colleagues in their practice and their primary care group or trust can be seen as one of a range of responses to these concerns and is central to the notion of clinical governance.

LIANE PAYNE

This paper will discuss how the notion of accountability in clinical governance can be understood and operationalised within primary care. It will use the clinical governance work of a London primary care group as a case study to illustrate mechanisms of accountability and will show how there are different forms of accountability between health professionals and others, relating to various aspects of performance. The paper will also consider the barriers to improved accountability and highlight tensions that are likely to arise.

Summary points

Clinical governance will extend primary health care professionals' accountability beyond current forms of legal and professional accountability

Clinical governance in primary care is aimed at enhancing the collective responsibility and accountability of professionals in primary care groups or trusts

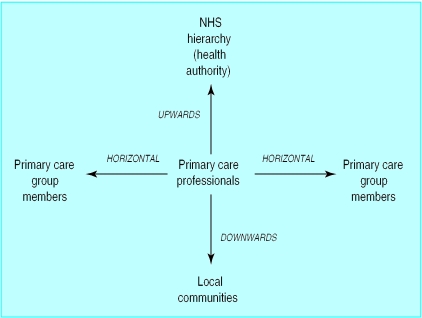

It is mainly concerned with increasing the accountability of primary health professionals to local communities (downwards accountability), the NHS hierarchy (upwards accountability), and their peers (horizontal accountability)

Primary care groups and trusts may find that, in addition to encouraging a culture of accountability, financial incentives are useful to achieve greater accountability

There are tensions between downwards and upwards accountability, and limited resources are likely to ensure that upwards accountability is given priority

Who is accountable?

In primary care, “who is accountable” can be divided into two groups: individual healthcare professionals and groups of professionals, such as primary care groups and trusts. The legal obligations for individual healthcare professionals to provide care of sufficiently high quality to individual patients predate clinical governance and will continue to exist in tandem with it. These are mainly dealt with by the law of negligence, under which a patient can sue a health professional for failing to have provided care of a reasonable standard. In addition, obligations imposed on individual professionals by their professional bodies (such as the General Medical Council) to provide care of adequate quality continue to exist.

In contrast to these mechanisms for individual accountability, the central aim of clinical governance is to hold groups of professionals accountable for each other's performance. One of the goals of clinical governance in primary care is to foster a new sense of collective responsibility for the quality of care provided by all primary care practitioners. This paper will concentrate on the collective notion of accountability in clinical governance.

Accountability to whom?

Primary care practitioners should regard themselves as accountable to a wide range of people:

The local community in which the practice is situated;

The NHS organisational hierarchy, represented, in the first instance, by the local health authority;

Peers in the primary care group or trust to which practitioners belong;

Actual patients who are treated in primary care; and

The regulatory organisation of the profession to which the healthcare professional belongs (for example, the General Medical Council for doctors and the United Kingdom Central Council for Nursing, Midwifery, and Health Visiting for nurses).

The last two groups are not the major concern of clinical governance, being covered primarily by the law of negligence and the disciplinary powers of the relevant profession respectively. Within primary care the novelty of clinical governance will lie in the development of public involvement in quality improvement work (characterised as downwards accountability) and the use of annual accountability agreements between primary care groups and trusts and the local health authority (characterised as upwards accountability). Comparing these developments with systems for quality assurance in general practice in other European countries, it is notable that in Germany, for example, emphasis remains mainly on legal liability to individual patients and professional self regulation and has not extended to the other forms of accountability envisaged by clinical governance in the United Kingdom.3

Primary care groups and trusts will also have to develop a new type of horizontal accountability to peers in the same organisation (figure). The relationships between primary care professionals are not governed by hierarchy or authority in the same way they would be in a hospital trust, requiring different systems of accountability. This is particularly relevant to doctors, for whom forthcoming regulations about revalidation4 and compulsory participation of individual practitioners in clinical audit5,6 complement the aims of clinical governance. The medical professional bodies will require participation in the activities of clinical governance for revalidation; though this will not be a legal obligation, it means that all doctors will have to comply if they wish to remain in practice.

Accountability for what?

Leat characterises accountability along four dimensions: fiscal, which concerns financial probity and thus the ability to trace and adequately explain all expenditure; process, which concerns the use of proper procedures; programme, which concerns the activities undertaken and, in particular, their quality; and priorities, which concerns the relevance or appropriateness of the activities chosen.7 All these aspects of accountability are relevant to the activities of clinical staff working in primary care, but process and programme accountability are most relevant to clinical governance.

Process accountability includes the need to show that appropriate systems are being used to record to whom care is being delivered and the way in which it is delivered. To fulfil the requirements of process accountability, primary care groups and trusts will need to show that staff are delivering care in accordance with the standards in national service frameworks, and also that any locally developed standards are adhered to. National service frameworks will contain detailed prescriptions of what activities should be undertaken in primary care settings. For example, the coronary heart disease framework sets a goal for primary care that by April 2001 “a systematically developed and maintained practice-based CHD register is in place and actively used to provide structured care to people with CHD.”8 Primary care groups and trusts will be expected to assess themselves against such milestones, and their progress will also be monitored by the NHS hierarchy.

Programme accountability includes the quality of the activities undertaken, which is the idea at the heart of clinical governance. Earlier in this series Rosen discussed the many dimensions of quality in primary care and the various models that have been developed to promote quality improvement in primary care.9 Of particular interest is the model of clinical governance developed by Baker et al, reflecting the complex activities of primary care.10 The authors identify multiple mechanisms for quality improvement, each of which is linked to an explicit method of accountability, such as production of an annual report, making audit results available to health authorities and patients, and involving patients in setting clinical governance priorities.

Mechanisms for establishing and maintaining accountability

The maintenance of downwards accountability to local communities by the NHS has generally proved difficult to achieve.11 Primary care groups and trusts are obliged to have some lay representation on their main boards; this is designed to strengthen their local accountability.12 Some primary care groups and trusts (including the one that will be used as a case study in this article) also have lay representation on their clinical governance subgroups. This is not where most effort to establish accountability is currently being made. Nevertheless, in existing examples of good practice, individual practices have been involving their patients in decisions about services provided13; these need to be built on by primary care groups and trusts.

Case study

Objectives concerning clinical governance in one primary care group's accountability agreement with its local health authority

Health improvement—This objective concerns the reduction of the impact of diabetes by preventing or delaying the onset of type 2 diabetes and maximising the health of those with diabetes. Two of the five actions under this objective involve clinical governance: agreeing standards for managing diabetes in primary care and targets for achievement, and establishing systems to record care and achieve those standards

Health outcomes of NHS care—This objective concerns reducing mortality and morbidity from coronary heart disease, reducing the prevalence of other smoking related diseases and improving general health as a result of increased physical activity and healthy eating. Two of the five actions under this objective involve clinical governance: agreeing standards for the management of coronary heart disease and stroke in primary care based on equivalent standards in local secondary care providers and establishing systems to record care and treatment for patients with coronary heart disease and stroke

The establishment of upwards accountability from primary care to the NHS hierarchy is to some extent a new element of accountability introduced with primary care groups and trusts. The system of performance management in the NHS has, until recently, concentrated on hospital and community services, as opposed to primary care.14 An annual accountability agreement must now be made between every primary care group and its local health authority. The box (above) presents the two objectives relating to clinical governance agreed by one London primary care group for its 1999/2000 accountability agreement with the health authority.

But primary care groups and trusts will not be able to carry out their obligations under their upwards accountability agreements unless they are able to establish horizontal accountability among the practices which make up the group or trust. This is likely to be achieved through a mixture of persuasion and peer pressure and, where possible, through financial incentives. Evidence from independent practitioner associations in New Zealand shows that collective accountability for the quality of care can be successfully fostered with the financial incentive of collective responsibility for a shared, cash limited budget, through which savings can be used to improve services.15

Primary care groups and trusts have mostly set up clinical governance subgroups to run the processes on a collective basis. These can build on experience of peer review gained from the existing systems of voluntary clinical audit in primary care and work undertaken by local pharmaceutical advisors to improve prescribing. Some total purchasing pilots also developed processes for horizontal accountability based on peer review of prescribing and referrals.16,17

The primary care group in the case study intends to use some financial incentives to implement clinical governance. Two forms of financial incentive are to be used. Firstly, a practice incentive scheme explicitly links incentives to clinical governance. Money will be paid to practices that reach the specific clinical governance targets in respect of coronary heart disease and diabetes. Monitoring of these targets and of the clinical performance of individual practices in general will be a vital component of this means of improving horizontal accountability. Secondly, the primary care group has decided that small financial incentives will be given for infrastructure development. For example, money could be used to improve the quality of patient records by developing systems for the consistent recording of clinical information.

Possible tensions between accountability to various groups

Nurses on the primary care group board may face conflicts between the priorities of the primary care group and those of their NHS Trust employer—for example, about attachment of nursing staff to practices

Individual general practitioners may face conflicts between the primary care group's collective need to curtail spending on drugs and their professional judgment as to the appropriate drugs to prescribe for certain patients

The primary care group as a whole may face conflicts between the need to plan and commission local community and hospital services within the budget available (which may entail closing some services), for which the primary care group is accountable to the central NHS via the Health Authority, and the demands of patients and local groups for services to remain open so that there are accessible local services

Making accountability happen

Primary care groups and trusts will face several challenges if they are to make real improvements in professional accountability. Firstly, clinical governance does not impose any new legal obligations on individual health professionals. The only new legal obligation, given in section 18(1) of the Health Act 1999, is that primary care trusts (along with health authorities and hospital trusts) must “put and keep in place arrangements for the purpose of monitoring and improving the quality of health care.”18 This broadly defined requirement can be seen as a way of fostering collective responsibility inside those organisations, rather than singling out individual professionals. The organisational developments needed to achieve this will be discussed later in this series.19 Such work will be important to foster the types of relationships between primary care group or trust members required for horizontal accountability to operate effectively. Organisational development work with primary care groups and trusts must aim to foster a culture of collective responsibility among staff, and one in which accountability to others is recognised as important and not just as a threat to individual professionals' autonomy.

Secondly, the aims and desires of the groups to whom professionals are accountable may not be compatible at all times—in particular, the views of the public at local level may not coincide with the goals of the centrally managed NHS, as manifested in the plans of the local health authority. For example, local populations are often opposed to the closing or downgrading of local facilities, such as hospitals, which the NHS hierarchy regards as surplus to requirements and inefficient to maintain operating in their current state. The box below gives some further examples of tensions that may arise between different aspects of health professionals' accountability.

Thirdly, establishing and maintaining horizontal and upwards accountability as part of clinical governance is likely to be costly. Health professionals will need time and appropriate skills, equipment, and facilities to undertake peer review and monitor the targets they set themselves. Money will be needed for financial incentives, if these are used. Additionally, if downwards accountability to local communities is taken seriously by primary care groups and trusts, this will require further expenditure on activities such as informing, training, and meeting with lay people to enable meaningful participation by the public.

Conclusions

Clearly, in the face of the limited resources being offered by health authorities, primary care groups and trusts will need to give priority to some elements of accountability. Horizontal accountability is important to develop early on, as it is the bedrock for effective clinical governance in primary care groups and trusts. Accountability for processes of care makes a good building block for further work, such as measuring actual outcomes of care. At the same time, it will be necessary for primary care groups and trusts to satisfy the requirements of upwards accountability to the NHS hierarchy.

Thus, primary care professionals will need to concentrate on a mixture of centrally identified clinical and organisational issues, particularly those set out in the national service frameworks, and issues identified in local health improvement programmes. Downwards accountability to communities of patients is likely to be the aspect of accountability which will have the least attention paid to it in the short term.

Figure.

Types of accountability

This is the second in a series of five articles

Footnotes

Series editor: Rebecca Rosen

References

- 1.Smith R. All changed, utterly changed. BMJ. 1998;316:1917–1918. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7149.1917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beecham L. Milburn sets up inquiry into Shipman case. BMJ. 2000;320:401. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pugner K. Quality uber alles? The German approach to clinical regulation. Br J Health Care Manage. 1998;4(12):4–7. [Google Scholar]

- 4.General Medical Council. GMC endorses revalidation proposal (10 February 1999). www.gmc-uk.org/standard/news/news.htm (accessed 21 July 2000).

- 5.Secretary of State for Health. Supporting doctors, protecting patients: a consultation paper on preventing, recognising and dealing with poor clinical performance of doctors in the NHS in England. London: Department of Health; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Royal College of General Practitioners. Good medical practice for general practitioners. London: RCGP; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leat D. Voluntary organisations and accountability. London: National Council of Voluntary Organisations; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Department of Health. National service framework for coronary heart disease: modern standards and service models. London: Department of Health; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosen R. Improving quality in the changing world of clinical care. BMJ. 2000;321:551–554. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7260.551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baker R, Lakhani M, Fraser R, Cheater F. A model of clinical governance in primary care groups. BMJ. 1999;318:779–783. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7186.779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Longley D. Public law and health service accountability. Buckingham: Open University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 12.NHS Executive. The new NHS: modern and dependable: developing primary care groups. Leeds: NHSE; 1998. . (HSC 1998/139.) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murray S, Tapson J, Turnbull L, McCallum J, Little A. Listening to local voices: adapting rapid appraisal to assess health and social needs in general practice. BMJ. 1994;308:698–700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6930.698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.NHS Executive. The new NHS: modern and dependable: a national framework for assessing performance. Leeds: NHSE; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Malcolm M, Mays N. New Zealand's independent practitioner associations: a working model of clinical governance in primary care? BMJ. 1999;319:1340–1342. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7221.1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goodwin N, Abbott S, Baxter K, Evans D, Killoran A, Malbon G, et al. The dynamics of primary care commissioning: a close up of total purchasing pilots. London: King's Fund; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Castlefields Health Centre. Annual report 1993-94. Runcorn: Castlefields Health Centre; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Health Act 1999. London: Stationery Office; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huntington J, Gillam S, Rosen R. Organisational development for clinical governance. BMJ 2000;321 (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]