Abstract

Purpose

We report a dosimetric study in whole breast irradiation (WBI) of plan robustness evaluation against position error with two radiation techniques: tangential intensity-modulated radiotherapy (T-IMRT) and multi-angle IMRT (M-IMRT).

Methods

Ten left-sided patients underwent WBI were selected. The dosimetric characteristics, biological evaluation and plan robustness were evaluated. The plan robustness quantification was performed by calculating the dose differences (Δ) of the original plan and perturbed plans, which were recalculated by introducing a 3-, 5-, and 10-mm shift in 18 directions.

Results

M-IMRT showed better sparing of high-dose volume of organs at risk (OARs), but performed a larger low-dose irradiation volume of normal tissue. The greater shift worsened plan robustness. For a 10-mm perturbation, greater dose differences were observed in T-IMRT plans in nearly all directions, with higher ΔD98%, ΔD95%, and ΔDmean of CTV Boost and CTV. A 10-mm shift in inferior (I) direction induced CTV Boost in T-IMRT plans a 1.1 (ΔD98%), 1.1 (ΔD95%), and 1.7 (ΔDmean) times dose differences greater than dose differences in M-IMRT plans. For CTV Boost, shifts in the right (R) and I directions generated greater dose differences in T-IMRT plans, while shifts in left (L) and superior (S) directions generated larger dose differences in M-IMRT plans. For CTV, T-IMRT plans showed higher sensitivity to a shift in the R direction. M-IMRT plans showed higher sensitivity to shifts in L, S, and I directions. For OARs, negligible dose differences were found in V20 of the lungs and heart. Greater ΔDmax of the left anterior descending artery (LAD) was seen in M-IMRT plans.

Conclusion

We proposed a plan robustness evaluation method to determine the beam angle against position uncertainty accompanied by optimal dose distribution and OAR sparing.

Keywords: left-sided breast, robustness, beam angle, intensity-modulated radiotherapy, position-error

Introduction

Whole-breast radiotherapy (WBRT) following breast-conserving surgery reduced local recurrence and breast cancer (BC) mortality.1–4 Cardio-protective strategies to further mitigate the injurious effects of radiotherapy (RT) are paramount for the cardiac complications that significantly affect the overall survival of BC patients. 5 Intensity-modulated radiation treatment (IMRT) technique provided an optimal dose distribution, sparing of heart and the left anterior descending artery (LAD), and improved the target dose homogeneity and conformity, compared to the conventional three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy (3D-CRT) technique. 6 Previous randomized trials implicated that the IMRT technique reduced acute radiation dermatitis, such as edema, erythema, moist desquamation, and breast pain.7–10 However, highly inverse optimized IMRT plans elevated the complexity of plans with smaller and irregular beam apertures and greater extent modulation of machine parameters, 11 thus further elevated the risk of inaccurate dose delivery induced by position error. Considering the higher risk of the IMRT technique, a deeper understanding of crucial factors associated with the robustness of IMRT plans is of pivotal significance to making a comprehensive evaluation by considering the plan robustness. 12

Tangential intensity-modulated radiotherapy (T-IMRT) adopted the beam angle arrangement of the former 3D-CRT technique, and improved the conformity and homogeneity compared to 3D-CRT. Multi-angle IMRT (M-IMRT) sets even beam angles in the same range as T-IMRT to acquire a higher degree of beam angle. T-IMRT and M-IMRT techniques generated different dose distributions and organ at risk (OAR) sparing. To the best of our knowledge, few studies have evaluated the plan robustness of beam angle arrangement in photon radiotherapy. Thus, we aimed to evaluate the plan robustness of two IMRT plans with different beam angle arrangements and provide a comprehensive description and a reference for clinical use.

Materials and Methods

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

The study was approved by the institutional review board of the National Cancer Center/National Clinical Research Center for Cancer/Cancer Hospital & Shenzhen Hospital (Approval number: KYLX2022-122).

Patients and Inclusion Criteria

Ten patients diagnosed with left-sided invasive, lymph-node negative BC or ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) and treated with breast-conserving surgery, were included in this retrospective planning study. We state that the consents for participation of data have been obtained from all patients. All the patients included in this study are above 18 years old.

CT Simulation and Delineation

All the patients were immobilized by a breast bracket (CIVCO Medical Solutions, Orange City, IA, USA) in a supine position. The computed tomography (CT) images with a slice thickness of 5.0 mm were acquired using a 16-slice CT scanner (GE Discovery RT, GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA). The clinical target volume (CTV), and clinical target volume boost (CTV Boost) were delineated by an experienced oncologist. The CTV was defined as the whole breast, and the CTV Boost was defined as a 2-cm margin of surgical clip. The plan target volume (PTV) and PTV Boost were generated by applying 5-mm radial and longitudinal margins from the CTV and CTV Boost, and subtracting the 5 mm of the skin surface. The OARs included bilateral lungs, heart, contralateral breast, the LAD, and esophagus.

Treatment Planning

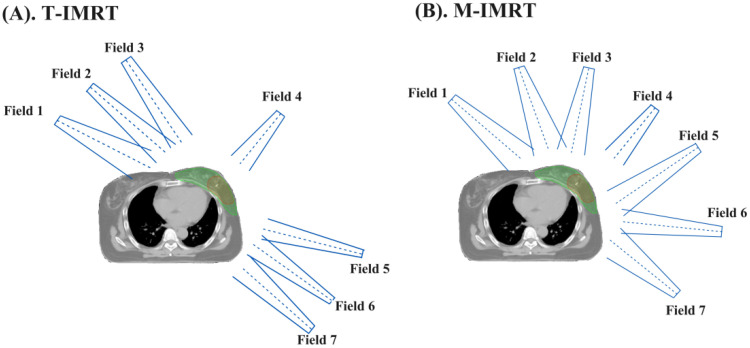

The T-IMRT and M-IMRT plans were generated using Varian Eclipse (13.6 Version) treatment planning system (TPS) modeled with the VitalBeam (Varian, Palo Alto, USA) linac. In our center, we followed the hypo-fractionated radiotherapy initiated by Department of Radiation Oncology, National Cancer Center/National Clinical Research Center for Cancer/Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College. 13 The prescription dose was 43.5 Gy in 15 fractions for PTV and a simultaneous integrated boost of 49.5 Gy in 15 fractions for PTV Boost. For T-IMRT plans (Figure 1(A)) contained 2 tangential fields and 4 neighboring fields spaced by ±10°. For M-IMRT plans (Figure 1(B)), the fields were set as equal interval angles within the range of the 2 tangential fields. In both T-IMRT and M-IMRT plans, field 4 was set as 30° with the irradiated area solely covering PTV Boost. The same optimization objective, convolution optimization, and iterative optimization were used. All the original plans were normalized so that ≥95% of the PTV and PTV Boost received 100% of the prescription dose.

Figure 1.

Beam arrangements of T-IMRT and M-IMRT plans. (A). T-IMRT; (B) M-IMRT.

Dosimetric Evaluation

The main parameters used to compare the T-IMRT and M-IMRT techniques were 98% dose coverage (D98%), 2 cm3 dose coverage (D2cc), mean dose (Dmean) of PTV and PTV Boost, and the 95% dose coverage (D95%) of PTV. For OARs, V20, V5, Dmean of the ipsilateral lung (Lung L); V20 and Dmean of heart, V5Gy and Dmean of the contralateral lung (Lung R); Dmean of the contralateral breast (Breast R), Dmax and Dmean of LAD and esophagus were evaluated. Dx% represented the dose (in Gy) received by x% of the volume, Vy the volume (in percentage) received by y Gy, and D2cc the dose (in Gy) received by a volume of 2 cm3. Dmean and Dmax represented the mean and max dose, respectively.

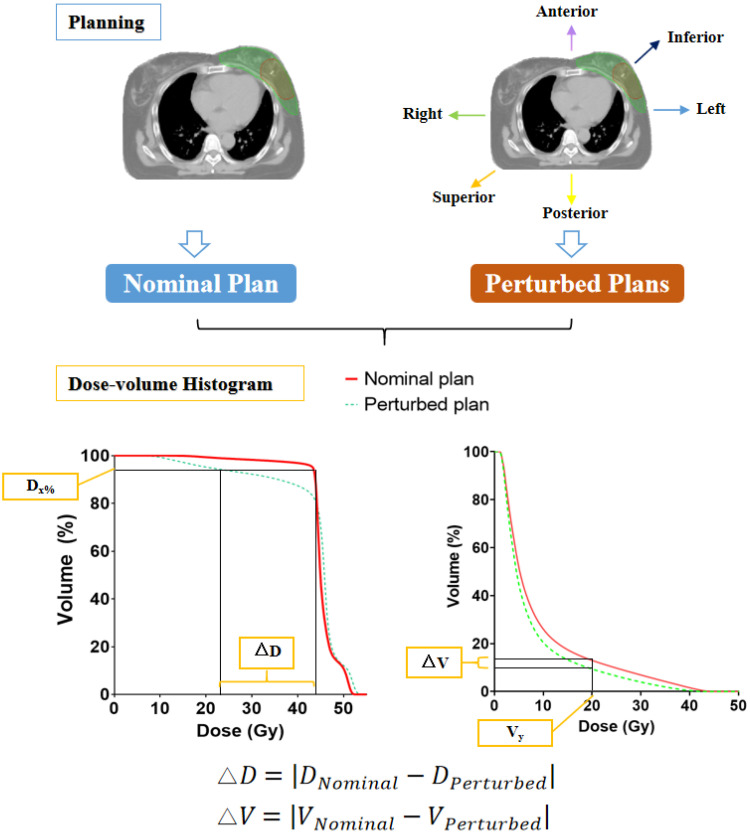

Robustness Quantification

Figure 2 illustrates the process of evaluating the robustness of T-IMRT and M-IMRT plans. We simulate the dose variations by introducing position shifts to the nominal plans. Eighteen perturbed plans were recalculated by shifting the isocenter from its reference point in the left-right (L-R), anterior-posterior (A-P), and superior-inferior (S-I) directions by 3, 5, and 10 mm. The differences in the dosimetric parameters (ΔDx% and ΔVy) between the perturbed plans and the nominal plan were calculated. The band of the specific dose parameter, such as an example of the band of D95%, is the region between the nominal and perturbed curves at D95%, and was associated with the plan robustness. The absolute value of the dose difference corresponded to the plan robustness for the structure. The smaller value correlated with a better robustness for certain dosimetric parameters.

Figure 2.

Steps in robustness evaluation of T-IMRT and M-IMRT plans.

Biological Evaluation

The tumor control probability (TCP) of CTV and CTV Boost were calculated for the biological evaluation. The Schultheiss logit model was adopted to calculate TCP, according to Equation (1).

| (1) |

TCD50 is the radiation dose that locally controls 50% of the tumor cells when the dose is homogeneously irradiated. The γ50 describes the slope of the dose–response curve at the value of TCD50. We set TCD50 as 30.89 Gy, γ50 as 1.3. 14 The equivalent uniform dose (EUD) was calculated according to Equations (2) and (3).

| (2) |

| (3) |

EQD2 represented the equivalent dose in 2 Gy per fraction, which depended on the fraction size and α/β ratio for each case. vi is the volume at dose Di. Parameters m and n are specific dose–response constants. 15 nf is the number of fractions. The α/β values of the breast and lung were 4.0, and 3.7 for the heart. 15 The TCP reduction (ΔTCP), which was the absolute value between the perturbed scenario and nominal scenario, corresponds to the plan robustness.

Statistical Analysis

We adopted either a two-tailed paired t-test (normal distribution) or the Wilcoxon signed-rank test (non-normal distribution) by using the IBM SPSS V22 software (IBM Incorporate, Armonk, USA). A p-value of less than 0.05 (*p < 0.05) was considered statistically significant.

Results and Discussion

PTV and PTV Boost Dosimetric Parameters

Both T-IMRT and M-IMRT plans were clinically acceptable. The dosimetric parameters of PTV, PTV Boost, and OARs were summarized in Table 1. No significant differences were observed in D2cc (p = 0.16), D98% (p = 0.49), and Dmean (p = 0.56) of PTV Boost. For PTV, T-IMRT exhibited lower D98% (** p = 0.009), D95% (p = 0.11) but higher Dmean (*p = 0.05). T-IMRT plans produced lower V5 (**p = 0.003) and Dmean (*p = 0.026), but with higher V20 (*p = 0.027) in the ipsilateral lung. Higher V20 (**p = 0.005) and Dmean (p = 0.131) of heart were observed in T-IMRT plans. M-IMRT plans had better sparing of LAD with lower Dmax (**p = 0.006) and Dmean (p = 0.098). M-IMRT plans generated a larger volume of normal tissue irradiated by low dose, resulting in higher V5 (**p = 0.008), Dmean (**p = 0.002) of the contralateral lung, higher Dmean (** p = 0.002) of the contralateral breast, and Dmax (* p = 0.039) and Dmean (** p = 0.001) of esophagus.

Table 1.

Dosimetric Parameters of PTV, PTV Boost, and OARs in T-IMRT and M-IMRT Plans.

| Evaluated items | T-IMRT | M-IMRT | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTV Boost | D2cc (Gy) | 53.39 ± 1.25 | 53.06 ± 1.05 | 0.160 |

| D98% (Gy) | 47.72 ± 2.92 | 48.17 ± 1.54 | 0.492 | |

| Dmean (Gy) | 50.94 ± 0.26 | 50.88 ± 0.36 | 0.559 | |

| PTV | D98% (Gy) | 37.13 ± 4.83 | 40.96 ± 1.74 | **0.009 |

| D95% (Gy) | 43.51 ± 0.25 | 43.69 ± 0.25 | 0.111 | |

| Dmean (Gy) | 46.21 ± 0.68 | 46.01 ± 0.67 | *0.049 | |

| Lung L | V20 (%) | 11.77 ± 3.06 | 11.32 ± 3.09 | *0.027 |

| V5 (%) | 31.34 ± 5.66 | 38.88 ± 9.53 | **0.003 | |

| Dmean (Gy) | 7.53 ± 1.24 | 7.86 ± 41.43 | *0.026 | |

| Heart | V20 (%) | 4.70 ± 1.85 | 3.45 ± 1.49 | **0.005 |

| Dmean (Gy) | 4.30 ± 1.09 | 4.64 ± 1.19 | 0.131 | |

| Lung R | V5 (%) | 0.05 ± 0.11 | 3.75 ± 2.65 | **0.008 |

| Dmean (Gy) | 0.25 ± 0.13 | 1.50 ± 0.35 | **0.002 | |

| Breast R | Dmean (Gy) | 0.49 ± 0.16 | 2.60 ± 0.97 | **0.002 |

| LAD | Dmax (Gy) | 46.21 ± 2.43 | 42.24 ± 3.34 | **0.006 |

| Dmean (Gy) | 22.70 ± 8.33 | 20.05 ± 5.82 | 0.098 | |

| Esophagus | Dmax (Gy) | 2.76 ± 3.08 | 9.67 ± 5.90 | *0.039 |

| Dmean (Gy) | 0.68 ± 0.45 | 2.36 ± 1.18 | **0.001 | |

The results were exhibited by the mean dose ± standard deviation (in bold *p values < 0.05 and **p values < 0.01).

Plan Robustness Evaluation

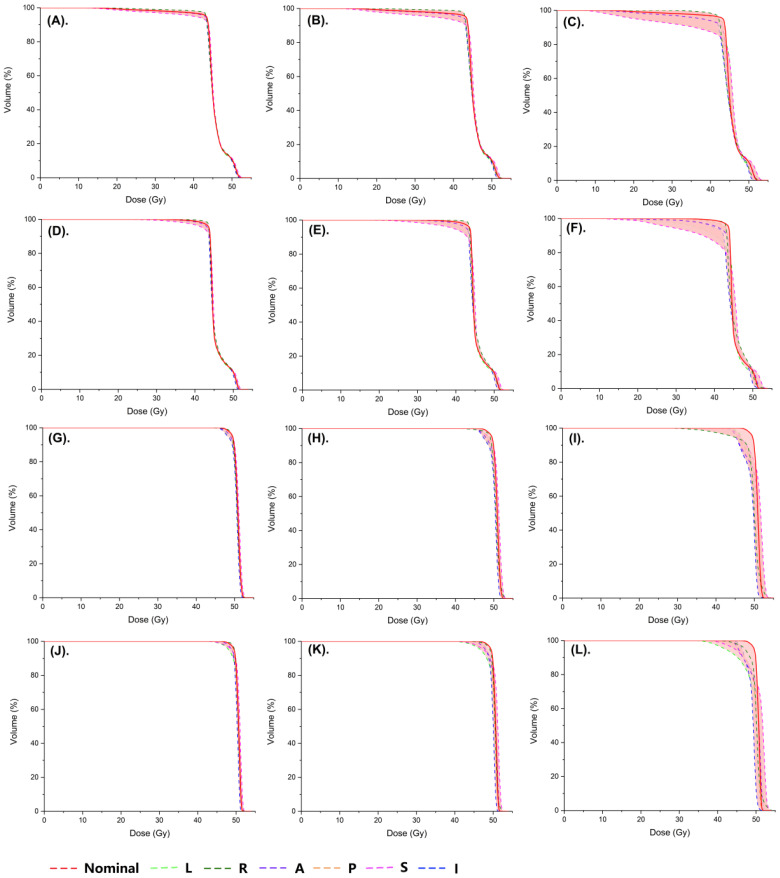

Figure 3 exhibited an example of dose-volume histogram of the nominal and perturbed plans for different isocenter shifts. The red solid line represented the nominal plan, while the colored dash lines represented the perturbed plans with position shifts in different directions. The band, which was marked in the pink shaded area, represented the degree of dose variation due to the position shift and was correspondent with plan robustness. When a 3-mm shift was introduced to the nominal plans, narrow bands were observed in both PTV (Figure 3(A), Figure 3(D)) and PTV Boost (Figure 3(G), Figure 3(J)) of T-IMRT and M-IMRT plans. When a 5-mm shift was introduced, an increased width of bands was found in PTV in both plans (Figure 3(B), Figure 3(E)). The width further increased with greater shifts. We noticed that the perturbed T-IMRT plans (Figure 3(C), especially in a 5- and 10-mm perturbed plan, resulted in an obvious decrease in the minimum dose of the PTV, which markedly increased the underdose risk of PTV. However, widened bands were observed in the PTV Boost of M-IMRT plans (Figure 3(K), Figure 3(L)) compared to T-IMRT plans (Figure 3(H), Figure 3(I)). We then further evaluated the dose differences of CTV and CTV Boost according to the formula (Figure 2).

Figure 3.

A sample of dose-volume histograms (DVHs) of the nominal and perturbed T-IMRT and M-IMRT plans for different isocenter shifts. (A) PTV of T-IMRT plans with a 3-mm shift; (B) PTV of T-IMRT plans with a 5-mm shift; (C) PTV of T-IMRT plans with a 10-mm shift; (D) PTV of M-IMRT plans with a 3-mm shift; (E) PTV of M-IMRT plans with a 5-mm shift; (F) PTV of M-IMRT plans with a 10-mm shift; (G) PTV Boost of T-IMRT plans with a 3-mm shift; (H) PTV Boost of T-IMRT plans with a 5-mm shift; (I) PTV Boost of T-IMRT plans with a 10-mm shift; (J) PTV Boost of M-IMRT plans with a 3-mm shift; (K) PTV Boost of M-IMRT plans with a 5-mm shift; (L) PTV Boost of M-IMRT plans with a 10-mm shift; PTV, plan target volume; PTV Boost, plan target volume boost; T-IMRT, tangential intensity-modulated radiation; M-IMRT, multiple-angle intensity-modulated radiation. L, left; R, right; A, anterior; P, posterior; S, superior; I, inferior.

We calculated the dose differences of D98%, D95%, and Dmean. The ΔD98%, ΔD95%, and ΔDmean of CTV Boost were summarized in Table 2. For a 3-mm perturbation, negligible ΔD98%, ΔD95%, and ΔDmean of CTV Boost were observed in both T-IMRT and M-IMRT plans. For a 5-mm perturbation, the shift in R and I directions exerted greater dose differences in ΔD98% of CTV Boost in T-IMRT plans (0.75 Gy for R direction, 1.40 Gy for I direction), while the shift in L and S directions induced greater dose differences in M-IMRT plans (1.13 Gy for L direction, 1.18 Gy for I direction). The shift in R and I directions generated greater dose differences in ΔD95% of CTV Boost in T-IMRT plans (0.63 Gy for R direction, 0.89 Gy for I direction), while the shift in L and S directions induced greater dose differences in M-IMRT plans (0.65Gy for L direction, 0.80 Gy for I direction). A 3- and 5-mm shift did not generate obvious dose differences of Dmean in both two techniques. For a 10-mm shift, greater dose differences were seen in T-IMRT plans in practically all directions, with higher ΔD98%, ΔD95%, and ΔDmean of CTV Boost. A 10-mm shift in S (5.47 Gy) and I (8.39 Gy) directions induced the maximum dose differences in ΔD98% of the T-IMRT plans. A 10-mm shift in I direction induced the largest ΔD95% and ΔDmean of CTV Boost in T-IMRT plans. Shifts in A-P directions induced negligible dose differences in both T-IMRT and M-IMRT plans.

Table 2.

Absolute Dose Difference of Clinical Target Volume Boost (CTV Boost) Between the Reference and Perturbed T-IMRT and M-IMRT Plans for Different Isocenter Shifts.

| Position error | CTV Boost | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔD98% | ΔD95% | ΔDmean | ||||

| T-IMRT (Gy) | M-IMRT (Gy) | T-IMRT (Gy) | M-IMRT (Gy) | T-IMRT (Gy) | M-IMRT (Gy) | |

| L (3 mm) | 0.31 (0.01–1.03) | 0.53 (0.02–2.00) | 0.27 (0.00–0.94) | 0.36 (0.04–1.72) | 0.19 (0.01–0.54) | 0.20 (0.03–0.82) |

| R (3 mm) | 0.37 (0.15–0.90) | 0.22 (0.16–0.39) | 0.35 (0.19–0.76) | 0.24 (0.15–0.40) | 0.25 (0.05–0.78) | 0.43 (0.01–1.48) |

| A (3 mm) | 0.14 (0.03–0.40) | 0.19 (0.01–0.95) | 0.10 (0.02–0.23) | 0.14(0.00–0.70) | 0.01 (0.01–0.16) | 0.06 (0.01–0.17) |

| P (3 mm) | 0.13 (0.03–0.21) | 0.10 (0.03–0.20) | 0.12 (0.00–0.24) | 0.09 (0.01–0.19) | 0.09 (0.03–0.21) | 0.08 (0.01–0.20) |

| S (3 mm) | 0.38 (0.03–1.52) | 0.61 (0.11–1.38) | 0.34 (0.01–1.08) | 0.40 (0.01–1.00) | 0.24 (0.08–0.40) | 0.23 (0.03–0.39) |

| I (3 mm) | 0.50 (0.23–0.87) | 0.37 (0.06–1.01) | 0.41 (0.19–0.59) | 0.29 (0.01–0.45) | 0.28 (0.12–0.55) | 0.26 (0.01–0.49) |

| L (5 mm) | 0.74 (0.04–1.64) | 1.13 (0.08–2.91) | 0.39 (0.06–1.49) | 0.65 (0.03–2.55) | 0.28 (0.02–0.74) | 0.28 (0.01–1.08) |

| R (5 mm) | 0.75 (0.32–1.75) | 0.39 (0.12–0.55) | 0.63(0.34–1.01) | 0.39(0.25–0.48) | 0.44 (0.09–1.34) | 0.80 (0.01–2.96) |

| A (5 mm) | 0.32 (0.00–0.75) | 0.42 (0.02–1.61) | 0.18 (0.06–0.47) | 0.27 (0.00–1.19) | 0.11 (0.03–0.23) | 0.09 (0.01–0.21) |

| P (5 mm) | 0.31 (0.11–0.92) | 0.22 (0.02–0.68) | 0.24 (0.03–0.67) | 0.18 (0.05–0.48) | 0.15 (0.02–0.47) | 0.16 (0.03–0.40) |

| S (5 mm) | 0.93 (0.08–3.99) | 1.18 (0.10–3.06) | 0.57 (0.02–2.07) | 0.80 (0.03–1.63) | 0.38 (0.11–0.50) | 0.37 (0.06–0.63) |

| I (5 mm) | 1.40 (0.10–3.96) | 0.93 (0.05–3.99) | 0.89(0.10–1.54) | 0.69 (0.01–1.98) | 0.48 (0.24–0.94) | 0.44 (0.03–0.90) |

| L (10 mm) | 4.01 (0.68–18.28) | 3.74 (0.99–8.46) | 1.39 (0.11–4.82) | 2.09 (0.00–4.82) | 0.37 (0.01–1.06) | 0.48 (0.04–2.04) |

| R (10 mm) | 4.20 (1.13–8.48) | 2.32 (1.34–3.77) | 2.36 (0.84–5.97) | 1.30 (0.72–2.00) | 0.87 (0.01–2.29) | 1.60 (0.33–6.16) |

| A (10 mm) | 2.72 (0.65–5.12) | 2.49 (1.33- 14.37) | 1.63 (0.11–4.31) | 1.44 (0.33–3.37) | 0.30 (0.01–0.66) | 0.20 (0.02–0.38) |

| P (10 mm) | 2.18 (0.41–6.17) | 2.03 (0.35–5.69) | 1.32 (0.03–5.68) | 1.10 (0.03–5.00) | 0.39 (0.00–1.69) | 0.45 (0.02–1.54) |

| S (10 mm) | 5.47 (0.75–24.06) | 4.07 (0.27–14.37) | 2.30 (0.08–9.67) | 2.14 (0.39–7.24) | 0.65 (0.00–1.38) | 0.59 (0.05–1.18) |

| I (10 mm) | 8.39 (1.76–20.67) | 4.69 (1.28–15.03) | 5.74 (1.04–16.35) | 3.36 (0.54–12.40) | 1.56 (0.21–2.55) | 1.20 (0.09–2.04) |

The results were exhibited by mean value and range (in bold data ΔDx% > 1 Gy).

The ΔD98%, ΔD95%, and ΔDmean of CTV were exhibited in Table 3. For a 3-mm perturbation, negligible ΔD98%, ΔD95%, and ΔDmean of CTV were observed in both T-IMRT and M-IMRT plans. For a 5-mm perturbation, ΔD98% and ΔD95% of CTV, shift in R direction exerted greater dose differences in T-IMRT plans (0.52 Gy (ΔD98%) and 0.50 Gy (ΔD95%)). The shift in L, S, and I directions induced greater ΔD98% (0.69 Gy (L), 1.21 Gy (S), and 1.62 Gy (I)) in M-IMRT plans. The shift in I direction induced higher ΔD95% (0.86 Gy) in T-IMRT plans. Both T-IMRT and M-IMRT plans exhibited lower sensitivity to shifts in A-P directions. Appreciably higher ΔDmean of CTV was observed in T-IMRT plans. For a 10-mm perturbation, substantial dose differences were seen in T-IMRT plans in all directions, with higher ΔD98%, ΔD95%, and ΔDmean of CTV. The maximum dose differences appeared in ΔD98% of the T-IMRT plans with a 10-mm shift in S (12.02 Gy) and I (9.93 Gy) directions. A 10-mm shift in the I direction induced the largest ΔD95% and ΔDmean of CTV.

Table 3.

Absolute Dose Difference of Clinical Target Volume (CTV) Between the Reference and Perturbed T-IMRT and M-IMRT Plans for Different Isocenter Shifts.

| Position error | CTV | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔD98% | ΔD95% | ΔDmean | ||||

| T-IMRT (Gy) | M-IMRT (Gy) | T-IMRT (Gy) | M-IMRT (Gy) | T-IMRT (Gy) | M-IMRT (Gy) | |

| L (3 mm) | 0.12 (0.01–0.56) | 0.32 (0.09–0.80) | 0.14 (0.09–0.17) | 0.14 (0.02–0.50) | 0.12 (0.03–0.23) | 0.10 (0.00–0.38) |

| R (3 mm) | 0.21 (0.02–0.35) | 0.16 (0.08–0.26) | 0.24 (0.08–0.35) | 0.15 (0.09–0.24) | 0.15 (0.04–0.28) | 0.12 (0.00–0.62) |

| A (3 mm) | 0.08 (0.00–0.15) | 0.12 (0.02–0.37) | 0.05 (0.00–0.09) | 0.07 (0.01–0.23) | 0.04 (0.00–0.08) | 0.04 (0.01–0.10) |

| P (3 mm) | 0.05 (0.01–0.12) | 0.06 (0.01–0.14) | 0.04 (0.00–0.08) | 0.05 (0.01–0.11) | 0.04 (0.00–0.08) | 0.05 (0.02–0.13) |

| S (3 mm) | 0.19 (0.00–0.84) | 0.53 (0.02–1.44) | 0.15 (0.01–0.23) | 0.29 (0.02–1.08) | 0.16 (0.04–0.30) | 0.15 (0.01–0.44) |

| I (3 mm) | 0.34 (0.03–0.84) | 0.43 (0.22–0.64) | 0.36 (0.12–0.61) | 0.29 (0.08–0.38) | 0.21 (0.00–0.44) | 0.16 (0.02–0.58) |

| L (5 mm) | 0.48 (0.03–2.34) | 0.69 (0.27–1.72) | 0.20 (0.08–0.47) | 0.27 (0.05–1.05) | 0.18 (0.04–0.34) | 0.17 (0.04–0.53) |

| R (5 mm) | 0.52 (0.24–0.92) | 0.35 (0.21–0.51) | 0.50 (0.34–0.65) | 0.30 (0.21–0.43) | 0.27 (0.08–0.51) | 0.23 (0.01–1.07) |

| A (5 mm) | 0.19 (0.03–0.32) | 0.28 (0.07–0.61) | 0.10 (0.00–0.21) | 0.15 (0.01–0.36) | 0.07 (001–0.14) | 0.06 (0.02–0.14) |

| P (5 mm) | 0.11 (0.00–0.27) | 0.15 (0.07–0.28) | 0.08 (0.01–0.18) | 0.11 (0.00–0.23) | 0.07 (001–0.12) | 0.08 (0.03–0.23) |

| S (5 mm) | 1.15 (0.08–6.55) | 1.21 (0.29–2.52) | 0.22 (0.03–0.67) | 0.57 (0.05–1.86) | 0.24 (0.04–0.42) | 0.25 (0.06–0.56) |

| I (5 mm) | 1.10 (0.60–2.73) | 1.62 (0.67–3.26) | 0.86 (0.45–1.48) | 0.73 (0.49–1.20) | 0.42 (0.07–0.84) | 0.26 (0.09–0.73) |

| L (10 mm) | 6.06 (0.35–17.05) | 2.80 (0.43–7.72) | 0.87 (0.04–3.69) | 0.85 (0.05–2.58) | 0.25 (0.05–0.45) | 0.28 (0.00–0.95) |

| R (10 mm) | 4.45 (1.60–8.23) | 2.32 (0.87–5.15) | 2.20 (0.90–3.59) | 1.01 (0.59–1.58) | 0.79 (0.28–1.46) | 0.50 (0.01–1.59) |

| A (10 mm) | 1.33 (0.06–3.95) | 1.20 (0.43–2.44) | 0.41 (0.09–0.81) | 0.47 (0.15–0.72) | 0.21 (0.04–0.34) | 0.15 (0.02–0.30) |

| P (10 mm) | 0.58 (0.05–1.77) | 0.79 (0.40–1.55) | 0.35 (0.06–0.81) | 0.40 (0.22–0.62) | 0.16 (0.00–0.38) | 0.15 (0.01–0.42) |

| S (10 mm) | 12.02 (0.65–25.55) | 8.74 (1.67–16.99) | 2.99 (0.04–13.41) | 2.63 (0.75–6.00) | 0.39 (0.08–1.20) | 0.52 (0.04–1.11) |

| I (10 mm) | 9.93 (3.97–16.66) | 9.21 (5.44–12.96) | 6.36 (1.58–13.73) | 5.72 (1.79–10.27) | 1.78 (0.90–3.06) | 1.03 (0.59–1.51) |

The results were exhibited by mean value and range (in bold data ΔDx% > 1 Gy).

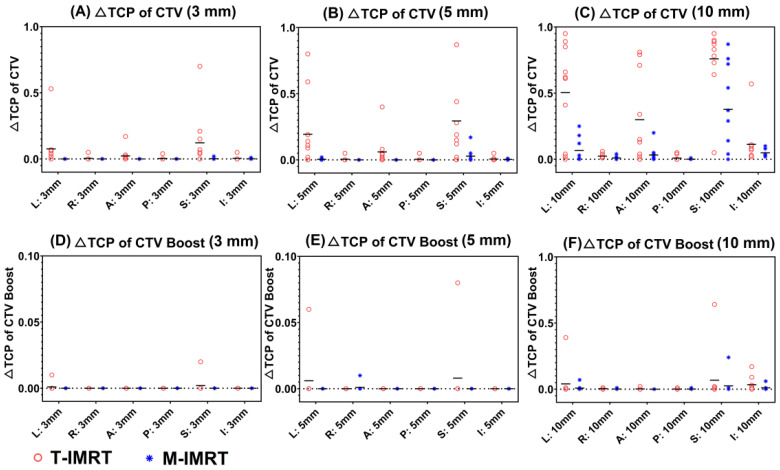

TCP Evaluation

We calculated the ΔTCP of CTV and CTV boost when the 3-, 5-, and 10-mm shifts were introduced to T-IMRT and M-IMRT plans. When a 3- and 5-mm shift were introduced, higher ΔTCP of CTV (Figure 4(A), Figure 4(B)) was observed in T-IMRT plans, especially in L and S directions. A 10-mm shift in the L, A, and S directions exerted substantial TCP reduction (Figure 4(C)) in T-IMRT plans. As to CTV Boost, inappreciable TCP reduction was seen for 3 mm (Figure 4(D)) and 5 mm perturbations (Figure 4(E)). 10 mm shift in L, S, and I directions exerted evident ΔTCP of CTV Boost (Figure 4(F)).

Figure 4.

TCP reduction (ΔTCP) of CTV and CTV Boost between the reference and perturbed T-IMRT and M-IMRT plans for different isocenter shifts. (A). ΔTCP of CTV (3 mm); (B). ΔTCP of CTV (5 mm); (C) ΔTCP of CTV (10 mm); (D). ΔTCP of CTV Boost (3 mm); (E). ΔTCP of CTV Boost (5 mm); (F) ΔTCP of CTV Boost (10 mm).

OAR Sparing

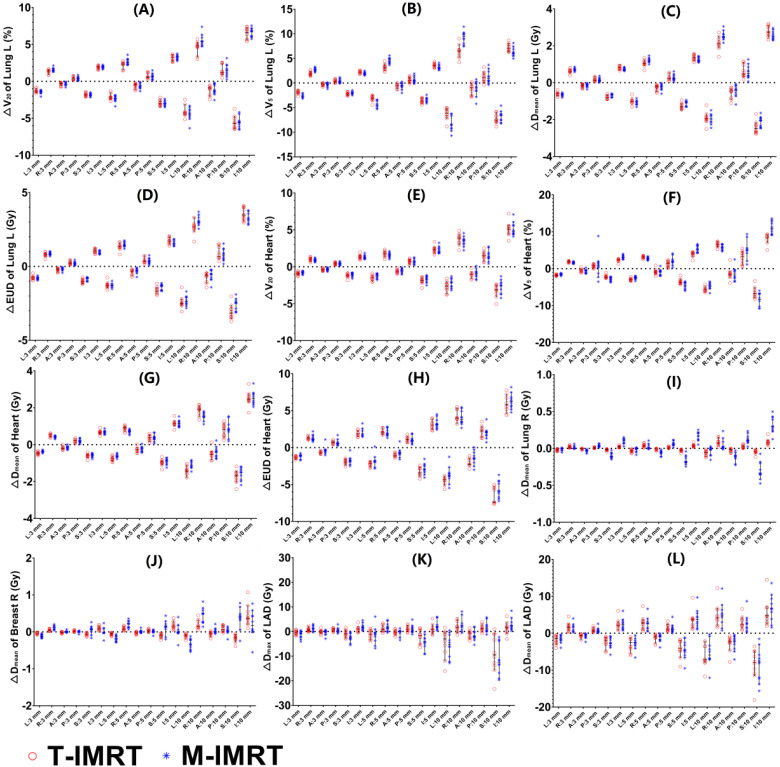

We calculated the dose differences of vicinal OARs including bilateral lungs, heart, LAD, and contralateral breast. Negligible differences of ΔV20 (Figure 5(A)), ΔV5 (Figure 5(B)), and ΔDmean (Figure 5(C)) of the ipsilateral lung were found between T-IMRT and M-IMRT plans. However, the ΔEUD (Figure 5(D)) of the ipsilateral lung in T-IMRT plans is slightly higher than that in M-IMRT plans. Similarly, inappreciable differences of ΔV20 (Figure 5(E)), ΔV5 (Figure 5(F)), and ΔDmean (Figure 5(G)) of the heart were found between T-IMRT and M-IMRT plans, but higher ΔEUD (Figure 5(H)) was observed in T-IMRT plans. M-IMRT had a larger ΔDmean of contralateral lung (Figure 5(I)) and breast (Figure 5(J)) than T-IMRT plans. The LAD exhibited the largest dose differences of ΔDmax (Figure 5(K)) and ΔDmean (Figure 5(L)), implicating a high risk of overdose in both T-IMRT and M-IMRT plans. The shift in S-I and L-R directions induced more noticeable dose differences than in A-P directions.

Figure 5.

Dose difference between the reference and perturbed T-IMRT and M-IMRT plans for different isocenter shifts. (A) ΔV20 of Lung L; (B) ΔV5 of Lung L; (C) ΔDmean of Lung L; (D) EUD of Lung L; (E) ΔV20 of heart; (F) ΔV5 of heart; (G) ΔDmean of heart; (H) EUD of heart; (I) ΔDmean of Lung R; (J) ΔDmean of Breast R; (K) ΔDmax of LAD; (L) ΔDmean of LAD.

Discussion

We compared the dosimetric parameters of T-IMRT and M-IMRT plans. Both T-IMRT and M-IMRT plans were clinically acceptable, with no significant differences of PTV and PTV Boost. T-IMRT improved the conformity and homogeneity of the target compared to CRT plans, however, retained a greater volume of OAR exposed to high dose. T-IMRT plans generated a higher V20, lower V5, and Dmean of the ipsilateral lung and the heart compared to M-IMRT plans. M-IMRT has a wider range of beam angles to perform better sparing the ipsilateral lung, heart, and LAD, but leading to a larger volume of normal tissue irradiated by low doses and higher mean doses of contralateral lung, breast, and esophagus. Previous studies indicated that the scattered radiation might increase the second primary cancer risk.16,17 Chao 18 carried out a study that involved 32 patients treated with IMRT and 58 patients treated with volumetric-modulated arc therapy (VMAT) for BC patients to evaluate the incidence of radiation-induced pneumonitis (RP) and secondary cancer risk (SCR). They suggested that lower V40 of the ipsilateral lung reduced the potential for inducing secondary malignancies and RP complications, and even larger low dose volume of contralateral breast slightly elevated the risk of SCR of breast. 18 M-IMRT significantly spared the max dose to LAD, and reduced the risk of coronary events, for the incidence of acute coronary events increased by 16.5% per Gy. 19 An optimal treatment plan tailored to solve a multi-criteria optimization problem to achieve the best trade-off between the optimal dose distribution, OAR sparing, and better clinical outcomes.

Besides, it should be noted that highly optimized plans generated complex plans. With the increased plan complexity, the risks of inaccurate dose calculation and treatment delivery were elevated, 11 compared to non-modulated plans. The accuracy of dose calculation and delivery might be reduced in highly complex plans.20,21 A study by Hirashima 22 uses plan complexity and dosiomics features to predict the performance of gamma passing rate, indicating the correlation between plan complexity and the accuracy of treatment plan dose delivery. Thus, we investigated the association between beam angle arrangement and plan robustness.

We evaluated the robustness of CTV Boost and CTV. A 3-mm position shift did not induce a marked dose difference (less than 1 Gy) in both T-IMRT and M-IMRT plans for CTV Boost and CTV. The greater shift worsened plan robustness. For a 10-mm perturbation, greater dose differences were observed in T-IMRT plans in almost all directions, with higher ΔD98%, ΔD95%, and ΔDmean of CTV Boost and CTV. A 10-mm shift in I direction induced the largest dose differences of CTV Boost, with 1.8 (ΔD98%), 1.7 (ΔD95%), and 1.3 (ΔDmean) times higher dose differences than those in M-IMRT plans. A 10-mm shift in I direction induced CTV Boost in T-IMRT plans a 1.1 (ΔD98%), 1.1 (ΔD95%), and 1.7 (ΔDmean) times dose differences higher than dose differences in M-IMRT plans. The physical dose differences induced biological dose variation and affected clinical outcomes to some degree. A 5- and 10-mm shift induced the T-IMRT plans greater ΔTCP of CTV Boost. Substantially higher ΔTCP of CTV in T-IMRT plans were observed in 3, 5, and 10 mm perturbed plans. Under dosage in the targets may result in the possibility of tumor recurrence, 15 for TCP predominately correlates with the minimum dose of tumor. 14 T-IMRT plans were less robust than M-IMRT plans for the beam angles in a narrow range amplifying the dose deviation caused by the position shift. The perturbed effect had been averaged in M-IMRT plans due to the wide range of beam angles.

Measurements should be taken to ensure the accurate dose delivery. Beyond the wide application of cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) and kilo-voltage image (KV) to minimize the set-up error, respiration-induced motion is a significant factor for geometric and dosimetric uncertainties during treatment planning and delivery. 23 Therefore, motion mitigation should be widely applied to obtain a precise dose delivery during radiotherapy. Optical surface-guided radiotherapy (SGRT), combining deep inspiration breath-hold (DIBH) technique obtained, not only lowers irradiated heart and LAD doses by pushing them away but also reproducible decreased target motion.24,25 Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), which is the administration of positive pressure to the airways during the entire respiratory cycle, was proved to be an effective strategy to reduce tumor motion. 26 The plan robustness was elevated in a small range of position shift for a 3-mm shift induced negligible dose differences in both CTV and CTV Boost based on our results of robustness evaluation. The pseudo skin flash strategy to open the leaf of the control points was considered an effective function application that could significantly reduce the possibility of insufficient tumor target caused by inspiratory motion and ensure sufficient tumor target exposure. 27

Meanwhile, plan robustness should be evaluated in highly optimized plans. In our study, the results suggested that IMRT plan robustness is correlated to beam angle selection. M-IMRT plans produced a larger low dose volume and a higher mean dose of contralateral lung and breast but spared high dose volume of ipsilateral lung, heart, and LAD and elevated plan robustness to some degree. This robustness evaluation should be taken into consideration to help determine the beam arrangement in highly optimized treatment plans. We noticed that different beam angles have different sensitivity to uncertainty in different directions. For CTV Boost, T-IMRT showed sensitivity to position shifts in the R and I directions, and M-IMRT showed sensitivity to position shifts in the L and S directions. For CTV, T-IMRT plans exhibit higher sensitivity to the shift in the R direction. M-IMRT plans exhibit higher sensitivity to shifts in L, S, and I directions. Both T-IMRT and M-IMRT plans exhibited lower sensitivity to shifts in A-P directions. The CTV-to-PTV margin method, adopted based on the Van Herk margin formula 28 in the margin-based treatment planning, aimed to ensure the dose coverage of CTV by blurring dose distribution. This may result in overdose or underdose,29,30 especially in highly optimized treatment plans, for the bluff dose of the margin should not be identified by geometric margin but the spatial location of the vicinal OAR and the steepness of required dose fall-off. Gordon JJ 31 proposed a coverage-based treatment planning (CBTP) to produce treatment plans that ensure target coverage by adjusting the margin until the specified CTV coverage is achieved, accompanied by CTV coverage probability analysis. The non-uniform beam-specific margin oriented towards different susceptibility with different beam arrangements may offer a new direction to improve the dose distribution and plan robustness.

Besides, empirical evidence suggested that plan robustness and plan complexity were positively correlated. 32 The key factors that are closely related to plan robustness and plan complexity should be clarified, such as modulation complexity scores (MCS), MLC aperture area variability (AAV), MLC leaf sequence variability (LSV), modulation index (MI), aperture area (AA), aperture perimeter (AP), aperture irregularity (AI), irregularity (PI), and plan-averaged beam modulation (PM) and so on, to interfere with plan quality and robustness.33,34

For OARs, no detectable dose differences in high dose volume (V20 of Lung L and V25 of Heart) were found, while M-IMRT plans exhibited slightly higher ΔV5 in bilateral lungs and Heart. Greater Dmax of LAD was seen in M-IMRT plans, for better LAD sparing in nominal M-IMRT plans generated steeper dose fall off. Levis 35 estimated the LAD PRV through the use of ECG-gated CT scans. They found that the LAD showed relevant displacements over the heart cycle, suggesting the need for a specific PRV margin to accurately estimate the dose received by these structures and optimize the planning process. Besides, the shifts in A-P directions exerted minimum dose difference, while S-I directions exerted maximum dose difference. Optimization using a LAD PRV with a non-uniform margin brings a new light to help mitigate the uncertainty by position shift.

Among the study's limitations, it has to be highlighted that the shifts were adopted in a single direction and calculated 18 times in each perturbed plan to simulate the dose deviation in one direction. Practically, the respiration-induced target motion was the combination of several directions in the regular breathing cycle. 36 During the breathing cycle, the tumor moved out of PTV, receiving a lower dose, then moved back, 36 resulting in a similar blurring effect for the respiration-induced relative motion is a regular event in a whole breathing cycle. Besides, the small size of the sample in a single institution was involved and the results were obtained according to our center's working protocols, which may reduce the statistical power and increase the margin of error. More quantitative research is in demand to define the plan robustness and plan quality evaluation.

Conclusions

We proposed a plan robustness evaluation method to determine the beam angle against position uncertainty accompanied with optimal dose distribution and OAR sparing. Different beam arrangements show different sensitivity to errors in different directions. The results can provide a reference for the clinical decision of adopting a non-uniform CTV-to-PTV margin to elevate plan robustness. More comprehensive measures of challenges in radiotherapy and treatment delivery may elevate the precision of treatment and ensure optimal clinical outcomes.

Footnotes

Authors Contributions: Zhen Ding did methodology, data Curation, and writing.

Kailian Kang and Wenjue Zhang performed data curation and preparation of tables.

Qingqing Yuan and Yong Sang did preparation of figures.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate: The study was approved by the institutional review board of National Cancer Center/National Clinical Research Center for Cancer/Cancer Hospital & Shenzhen Hospital. We confirm that all methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Sanming Project of Medicine in Shenzhen, Shenzhen High-level Hospital Construction Fund, Shenzhen Key Medical Discipline Construction Fund, Hospital Research Project, (grant numbers SZSM201612063, SZXK013, SZ2020QN006).

ORCID iDs: Zhen Ding https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6002-8863

Yong Sang https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0302-015X

References

- 1.Xiang X, Ding Z, Feng L, Li N. A meta-analysis of the efficacy and safety of accelerated partial breast irradiation versus whole-breast irradiation for early-stage breast cancer. Radiat Oncol. 2021;16(1):24. doi: 10.1186/s13014-021-01752-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haviland JS, Owen JR, Dewar JA, et al. The UK Standardisation of Breast Radiotherapy (START) trials of radiotherapy hypofractionation for treatment of early breast cancer: 10-year follow-up results of two randomised controlled trials. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(11):1086‐1094. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70386-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whelan TJ, Pignol JP, Levine MN, et al. Long-term results of hypofractionated radiation therapy for breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(6):513‐520. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0906260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG), Darby S, McGale P, et al. Effect of radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery on 10-year recurrence and 15-year breast cancer death: meta-analysis of individual patient data for 10,801 women in 17 randomised trials. Lancet. 2011;378(9804):1707‐1716. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61629-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bantema-Joppe EJ, Vredeveld EJ, de Bock GH, et al. Five year outcomes of hypofractionated simultaneous integrated boost irradiation in breast conserving therapy; patterns of recurrence. Radiother Oncol. 2013;108(2):269‐272. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2013.08.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu H, Chen X, He Z, Li J. Evaluation of 3D-CRT, IMRT and VMAT radiotherapy plans for left breast cancer based on clinical dosimetric study. Comput Med Imaging Graph. 2016;54(12):1‐5. doi: 10.1016/j.compmedimag.2016.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pignol JP, Olivotto I, Rakovitch E, et al. A multicenter randomized trial of breast intensity-modulated radiation therapy to reduce acute radiation dermatitis. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(13):2085‐2092. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.2488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mukesh MB, Barnett GC, Wilkinson JS, et al. Randomized controlled trial of intensity-modulated radiotherapy for early breast cancer: 5-year results confirm superior overall cosmesis. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(36):4488‐4495. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.7842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mukesh MB, Qian W, Wah Hak CC, et al. The Cambridge breast intensity-modulated radiotherapy trial: comparison of clinician- versus patient-reported outcomes. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2016;28(6):354‐364. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2016.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pignol JP, Truong P, Rakovitch E, Sattler MG, Whelan TJ, Olivotto IA. Ten years results of the Canadian breast intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) randomized controlled trial. Radiother Oncol. 2016;121(3):414‐419. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2016.08.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hernandez V, Hansen CR, Widesott L, et al. What is plan quality in radiotherapy? The importance of evaluating dose metrics, complexity, and robustness of treatment plans. Radiother Oncol. 2020;153(12):26‐33. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2020.09.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ding Z, Zeng Q, Kang K, et al. Evaluation of plan robustness using hybrid intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) and volumetric arc modulation radiotherapy (VMAT) for left-sided breast cancer. Bioengineering (Basel). 2022;9(4):131. doi: 10.3390/bioengineering9040131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang SL, Fang H, Hu C, et al. Hypofractionated versus conventional fractionated radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery in the modern treatment era: a multicenter, randomized controlled trial from China. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(31):3604‐3614. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.01024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luxton G, Keall PJ, King CR. A new formula for normal tissue complication probability (NTCP) as a function of equivalent uniform dose (EUD). Phys Med Biol. 2008;53(1):23‐36. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/53/1/002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.. Qi XS, White J, Li XA. Is α/β for breast cancer really low? Radiother Oncol. 2011;100(2):282‐288. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2011.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Filippi AR, Ragona R, Piva C, et al. Optimized volumetric modulated arc therapy versus 3D-CRT for early stage mediastinal Hodgkin lymphoma without axillary involvement: a comparison of second cancers and heart disease risk. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2015;92(1):161‐168. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2015.02.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Corradini S, Ballhausen H, Weingandt H, et al. Left-sided breast cancer and risks of secondary lung cancer and ischemic heart disease: effects of modern radiotherapy techniques. Strahlenther Onkol. 2018;194(3):196‐205. doi: 10.1007/s00066-017-1213-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chao PJ, Lee HF, Lan JH, et al. Propensity-score-matched evaluation of the incidence of radiation pneumonitis and secondary cancer risk for breast cancer patients treated with IMRT/VMAT. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):13771. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-14145-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van den Bogaard VA, Ta BD, van der Schaaf A, et al. Validation and modification of a prediction model for acute cardiac events in patients with breast cancer treated with radiotherapy based on three-dimensional dose distributions to cardiac substructures [published correction appears in J Clin Oncol. 2017 Nov 10;35(32):3736]. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(11):1171‐1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Younge KC, Matuszak MM, Moran JM, et al. Penalization of aperture complexity in inversely planned volumetric modulated arc therapy. Med Phys. 2012;39(11):7160‐7170. 10.1118/1.4762566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Götstedt J, Karlsson Hauer A, Bäck A. Development and evaluation of aperture-based complexity metrics using film and EPID measurements of static MLC openings. Med Phys. 2015;42(7):3911‐3921. 10.1118/1.4921733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hirashima H, Ono T, Nakamura M, et al. Improvement of prediction and classification performance for gamma passing rate by using plan complexity and dosiomics features. Radiother Oncol. 2020;153(12):250‐257. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2020.07.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao Y, Diao P, Zhang D, et al. Impact of positioning errors on the dosimetry of breath-hold-based volumetric arc modulated and tangential field-in-field left-sided breast treatments. Front Oncol. 2020;10:554131. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.554131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Naumann P, Batista V, Farnia B, et al. Feasibility of optical surface-guidance for position verification and monitoring of stereotactic body radiotherapy in deep-inspiration breath-hold. Front Oncol. 2020;10:573279. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.573279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gaál S, Kahán Z, Paczona V, et al. Deep-inspirational breath-hold (DIBH) technique in left-sided breast cancer: various aspects of clinical utility. Radiat Oncol. 2021;16(1):89. doi: 10.1186/s13014-021-01816-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jacobson G, Lawrence YR, Appel S, et al. Benefits of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) during radiation therapy: a prospective trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2021;110(5):1466‐1472. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2021.03.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang L, Qiu G, Yu J, et al. Effect of auto flash margin on superficial dose in breast conserving radiotherapy for breast cancer. J Appl Clin Med Phys. 2021;22(6):60‐70. doi: 10.1002/acm2.13287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van Herk M. Errors and margins in radiotherapy. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2004;14(1):52‐64. doi: 10.1053/j.semradonc.2003.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou G, Xu S, Yang Y, et al. SU-E-J-19: how should CTV to PTV margin be created—analysis of set-up uncertainties of different body parts using daily image guidance. Med Phys. 2012;39(6 Part 6):3656‐3656. doi: 10.1118/1.4734852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boekhoff MR, Defize IL, Borggreve AS, et al. CTV-to-PTV margin assessment for esophageal cancer radiotherapy based on an accumulated dose analysis. Radiother Oncol. 2021;161(8):16‐22. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2021.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gordon JJ, Siebers JV. Coverage-based treatment planning: optimizing the IMRT PTV to meet a CTV coverage criterion. Med Phys. 2009;36(3):961‐973. doi: 10.1118/1.3075772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Whitacre JM, Bender A. Networked buffering: a basic mechanism for distributed robustness in complex adaptive systems. Theor Biol Med Model. 2010;7(6):20. doi: 10.1186/1742-4682-7-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li C, Tao C, Bai T, et al. Beam complexity and monitor unit efficiency comparison in two different volumetric modulated arc therapy delivery systems using automated planning. BMC Cancer. 2021;21(1):261. doi: 10.1186/s12885-021-07991-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nguyen M, Chan GH. Quantified VMAT plan complexity in relation to measurement-based quality assurance results. J Appl Clin Med Phys. 2020;21(11):132‐140. doi: 10.1002/acm2.13048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Levis M, De Luca V, Fiandra C, et al. Plan optimization for mediastinal radiotherapy: estimation of coronary arteries motion with ECG-gated cardiac imaging and creation of compensatory expansion margins. Radiother Oncol. 2018;127(3):481‐486. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2018.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Engelsman M, Damen EM, De Jaeger K, et al. The effect of breathing and set-up errors on the cumulative dose to a lung tumor. Radiother Oncol. 2001;60(1):95‐105. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(01)00349-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]