Abstract

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), endemic areas of leishmaniosis have spread and the number of reported cases has increased. Europe is one of the continents with greatest risk of the re-emergence of this zoonosis. The significance of the cat as a reservoir of Leishmania species and not simply an accidental host seems to be gaining ground, mainly because: (i) cats can present increased seropositivity between serological analyses, but the pattern of seropositivity is not consistent between cats; (ii) cats can be infected for some months and thus are available for sandflies; and (iii) cats transmit the Leishmania species agent in a competent form. Furthermore, cats have behavioural characteristics that contribute to infection by Leishmania infantum and, as such, feline leishmaniosis (FeL) has been reported worldwide. When clinical signs of FeL are present, they are non-specific and frequently occur in other feline diseases. If they go undiagnosed, they can contribute to an underestimation of the actual occurrence of the disease in cats. The low seroprevalence titres, along with the commonly asymptomatic infection in cats, can further contribute to the underestimation of FeL occurrence. This work aims to raise awareness about FeL among veterinarians by providing a review of the current status of FeL infection caused by L infantum worldwide, the major clinicopathological features of infection, along with recent developments on FeL diagnosis, treatment and prevention.

Epidemiology of feline leishmaniosis

Leishmaniosis is a parasitic disease caused by an obligate intracellular protozoan of the genus Leishmania (Kinetoplastida, Trypanosomatidae). 1 Species from the genus Leishmania are subdivided in two subgenera: Leishmania (includes species from the Old World, namely L major, L infantum, L donovani and L tropica, and those found in the New World, namely L chagasi [syn L infantum], L mexicana, L amazonensis and L venezuelensis) and Viannia (only occurring in Central and South America; eg, species L [Viannia] braziliensis).1–3 Species from genus Leishmania identified as infective for felids include L infantum,1,2 L mexicana, 3 L venezuelensis, 4 and L (Viannia) braziliensis.5,6 Most L infantum strains belong to zymodeme MON-1, assumed to be responsible for zoonotic leishmaniosis, affecting humans, canids, felids and other hosts.7–11

The vectors of Leishmania species belong to the genus Phlebotomus (Diptera, Psychodidae) in the Old World and Lutzomya in the New World.12,13

Leishmaniosis in domestic cats (Felis catus) was described for the first time in 1912, in Algeria, in a cat that lived with a dog and a child, both infected with leishmaniosis. 14 Since then, as summarised in Table 1, feline leishmaniosis (FeL) has been globally reported, but it is found more frequently in countries bordering the Mediterranean Sea. 26 On the American continent, FeL has been reported particularly in Central America, 3 Brazil16,19 and Paraguay. 18

Table 1.

Compilation of worldwide epidemiological surveys of feline leishmaniosis due to Leishmania infantum

| Country (region) | Seroprevalence (total number of samples) | Diagnostic assay (cut-off titre) | Confirmatory assay: results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Italy (Milan) 15 | 25.3% (233) | IFI (1:80) | qPCR: 0% |

| Brazil (Araçatuba) 16 | 4.64% (302) | IFI (1:40) | ELISA: 12.91% |

| Direct parasitological exam: 9.93% | |||

| Mexico (Yucatan Peninsula) 17 | 22.1% (95) | ELISA (Fe-SOD) | – |

| Paraguay (Asuncion) 18 | 0.94% (317) | IFI | – |

| Brazil (Araçatuba) 19 | 25.4% (55) | ELISA | |

| 10.9% (55) | IFI (1:40) | – | |

| Iran 20 | 9.23% (195) | Immunochromatography | – |

| Portugal (Lisbon) 10 | 1.3% (76) | IFI | PCR: 20.3% (28/138) |

| Portugal (north region) 9 | 2.8% (316) | DAT | |

| ELISA | – | ||

| Greece (north region) 21 | 3.87% (284) | ELISA | – |

| Israel (Jerusalem) 22 | 6.7% (104) | ELISA | – |

| Portugal (Lisbon) 23 | 20% (20) | IFI | PCR: 30.4% (7/23) |

| Spain (south region) 2 | 60% (183) with titre ⩾10 | IFI | PCR: ELISA: 25.7% |

| 28.3% (183) with titre ⩾40 | Direct parasitological exam: 3/7 tested positive | ||

| Italy 24 | 16.3% (203) | IFI | – |

| Italy 25 | 0.9% (110) | IFI | – |

DAT = direct agglutination test; Fe-SOD = iron superoxide dismutase; IFI = indirect immunofluorescence; qPCR = quantitative polymerase chain reaction

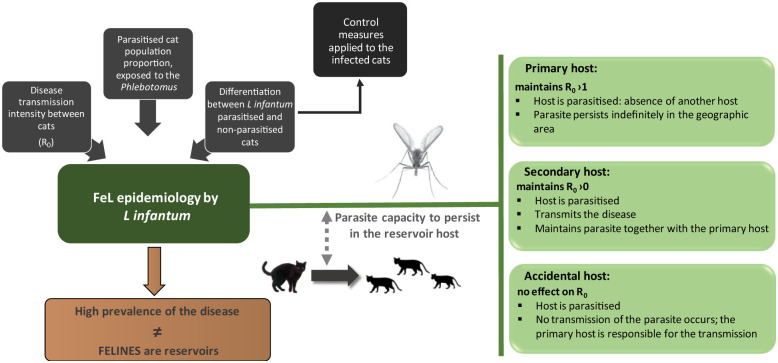

Recent cases and studies involving the occurrence of L infantum in cats suggest that these animals act as a reservoir.11,26–28 The classification of cats as accidental hosts or primary or secondary reservoirs remains an ongoing discussion.11,26–28 The classification of a host as primary, secondary (synonymous with minor) or accidental is based on the capacity of Leishmania species to persist, indefinitely or temporarily, in a population that is a reservoir of the disease, characterised by a basic reproduction number (R0), 29 as schematically depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Proposed flow chart for the study of the role of the cat in the epidemiology of Leishmania infantum infection (modified from Quinnell and Courtenay 29 ). R0 = basic reproduction number

Available data from epidemiological surveys (Table 1) and case reports (Table 2) suggest that the cat can act as a reservoir host of L infantum but not as an accidental host. 36 Possible justifications include8,10,28,37: (1) cats can be infected and do not develop illness – even if they present clinical signs, a chronic presentation will ensue; (2) in the peripheral blood of cats, the protozoan is in an infective form to the vector; (3) cats cohabit with human beings, namely in endemic areas of canine leishmaniosis (CaL) and (4) sick cats infected with Leishmania species do not recover without anti-leishmanial therapy.

Table 2.

Compilation of worldwide case reports of feline leishmaniosis due to Leishmania infantum

| Country (region) | Cat identification | Clinical signs | Diagnostic assay |

|---|---|---|---|

| France (south, St André Roche) 30 | 14-year-old male cat | Papular and ulcerative dermatitis at the base of the ear, head and interscapular region; weight loss; history of recurrent pododermatitis | Histopathology Western blotting qPCR Blood culture |

| Portugal (Porto) 31 | 4-year-old female cat | Depression and reduced appetite; severe non-regenerative anaemia; pancytopenia Mild increase in γ-globulin concentration |

Bone marrow cytology Buffy coat cytology PCR Indirect haemagglutination (1:100) |

| France (south, Biot) 7 | 6-year-old female cat | Whole-body cutaneous lesions with depilation and ulcero-crusted seborrhoeic dermatitis; emaciation | Histopathology Bone marrow cytology PCR Western blotting Direct agglutination (1/10240) |

| France (south, Grasse) 8 | 13-year-old neutered male cat | Ulcerative lesion in the left temporal region, initially reported as discrete crusts, with concurrent diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma; splenomegaly | IFI ELISA Histopathology Western blotting Blood culture |

| Spain (Barcelona) 32 | 8-year-old female cat | Slightly depressed, thin and poor-quality coat; moderate diffuse gingivitis and marked faucitis; bilateral panuveitis and secondary glaucoma; mild azotaemia, hyperglobulinaemia and moderate polyclonal gammopathy; diabetes mellitus | ELISA Ocular histopathology Bone marrow cytology PCR |

| Brazil (São Paulo) 33 | 2-year-old male cat | Nodular lesion on the nose; weight and muscle loss; lymphadenomegaly | IFI (1:80) PCR |

| Italy 34 | 14-year-old female cat | Anorexia and respiratory distress; emaciated and dehydrated; small crusty ulcer (0.5 cm), haematic cyst | IFI (1:640) Lesions cytology |

| 6-year-old male cat | History of bite abscess and aural itchiness; acute upper respiratory tract infection; popliteal lymphadenomegaly | Lymph node cytology PCR IFI (1:1280) |

|

| 10-year-old female cat | Anorexia, weight loss, depression; uveitis; severe non-regenerative anaemia, leukopenia and thrombocytopenia | Lymph node cytology PCR IFI (1:640) |

|

| Adult male cat | Persistent submandibular lymphadenomegaly, stomatitis and severe periodontitis; history of generalised alopecia and deep ulcers around the neck and weight loss | Lymph node cytology PCR IFI (1:640) |

|

| Italy (Imperia) 25 | 6-year-old female cat | Lethargy and an ulcerated nodule on the eyelid; weight loss, dysorexia; severe ulcerative stomatitis, generalised lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly | IFI (1:80) Histopathology Lesion and lymph node cytology PCR Electron microscopy |

| Spain 35 | 3-year-old female cat | History of abortion; recurrent alopecia of abdomen and neck; desquamation and erythema of the edge of the ears | IFI (1:160) Popliteal lymph node cytology |

| 5-year-old female cat | Severe jaundice and vomiting | Histopathology Electron microscopy |

IFI = indirect immunofluorescence; qPCR = quantitative polymerase chain reaction

Additionally, cats have behavioural characteristics that can contribute to exposure. They are nocturnal predators, operating in a 1.5 km radius of their residence, using forests as hunting territory. These are ideal elements to link the sylvatic and domestic cycles, favouring the dissemination of parasites. 38 Cats are thus considered as disease amplifiers. 15

Pathogenesis and lesions

The classification as accidental host is further challenged by evidence that felids are usually asymptomatic.10,22,26 In a study comprising 200 cats, only two animals revealed clinical signs, specifically crusty lesions of the dorsal cervical region along with hepatosplenomegaly. 39 Clinical manifestations of the disease comprise visceral, cutaneous and mucosal signs. Visceral signs are associated with high mortality and systemic involvement of the organism. Cutaneous or mucocutaneous signs are frequently associated with dissemination of parasites through other tissues, causing significant morbidity.11,35,38

The first reported cases of FeL were characterised by cutaneous manifestations, without visceral involvement,4,7,34,35,40 with dry local lesions in the form of papules and nodules, and exudative lesions in the form of crusts and ulcers.11,28 The importance of screening cats presenting dermatitis, nodular or ulcerative, was further shown by Navarro et al 38 who described 15 cats infected with leishmaniosis presenting cutaneous expression of the illness, namely skin lesions in the mucocutaneous junction (nose, lips and ears) as well as ocular lesions. Granulomatous perifoliculitis, lichenoid dermatitis and pododermatitis were also described. 41 Similarly, a clinical case of a 14-year-old cat positive for feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV), with a 3 year history of recurrent pododermatitis, unresponsive to antibiotics and characterised by exudative and erythematosus lesions, was reported. Besides a 20% weight loss, the cat presented three circumscribed cutaneous injuries (at the base of the ear, head and interscapular region), all with ulcerated or haemorrhagic papules. The histopathological examination of these cutaneous lesions revealed the presence of macrophages, with cytoplasmic inclusion bodies, consistent with Leishmania species forms. A complete parasitological examination of the skin biopsy further confirmed Leishmania species. A fourth lesion in the auricular pavilion was consistent with squamous cell carcinoma. 30

Lymphadenomegaly was also frequently reported, accompanied by fever, scaling and alopecia of the head and abdomen, ulcers on bony prominences, history of abortion, 35 mild periodontitis, 28 onychogryphosis, cachexia with muscular atrophy and weakness. 42

Moreover, ocular leishmaniosis was described as featuring ocular lesions such as corneal exudative ulcers, panuveitis and panophthalmitis.32,38 Although seldom found, cats with visceral leishmaniosis but without cutaneous signs have also been reported, presenting fever, jaundice, vomiting, lymphadenomegaly, lesions of the oral mucosa with gingivitis, anaemia and leukopenia.28,31,32 Renal failure associated with FeL has also been described, 38 although it is less evident than in dogs. Indeed, in dogs renal failure is a well-recognised syndrome and a cause of death.

A synergism between squamous cell carcinoma and FeL has been proposed, given that while the carcinoma could take advantage of the proliferation of the protozoan, the parasite could initiate the development of the neoplasia, or both. Lesions compatible with squamous cell carcinoma were described in the left temporal region 8 and in the auricular pavilion 30 of two FIV-positive cats. It is noticeable that FIV and/or feline leukaemia virus (FeLV) infections were referred to as FeL predisposing factors based on the ensuing immunosuppression.34,39,43 Supporting studies found a strong association (~70%) for cats between leishmaniosis and FIV, 34 and even a statistically significant correlation with FeL and FIV 16 and FeLV. 44 However, other studies contradict this positive correlation between FIV and/or FeLV and FeL infection.7,10,24,26,28,31,33,40–42

Other agents with a significant prevalence among feline populations and with a possibility of serological cross-reaction with Leishmania species can be mentioned. Regarding Toxoplasma gondii, of which cats are considered reservoirs, the majority of the studies did not observe a positive correlation between both infections.9,22,41,44 Coinfection with feline infectious peritonitis 33 or Trypanosoma cruzi 17 were considered of minor significance.

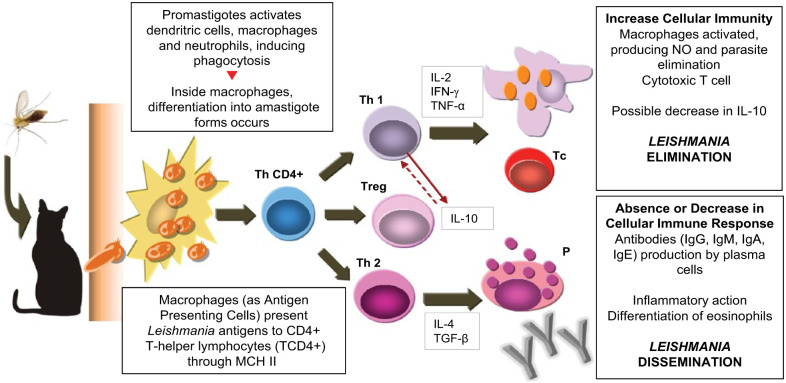

Immunological features of leishmaniosis

Based on CaL, we can assume that, in cats, leishmaniosis involves cell-mediated immunity (CMI), with activation of macrophages for the destruction of the amastigote forms. The high antibody titres (Table 2), present in some symptomatic cats, do not confer immunity against the disease. 45 Nevertheless, some investigations have shown that animals with increased titres of anti-Leishmania antibodies presented decreased positivity in PCR, whereas the biggest positivity through PCR occurred more frequently in cats with reduced antibody titres.2,39 This suggests that the immune response in felids differs from the response observed in dogs, explaining the high number of asymptomatic infected cats, and the variable clinical manifestation of the disease, showing that lesions occur before the production of antibodies. When these lesions are in a resolution phase, seroconversion occurs, suggesting that the humoral immune response is protective in FeL. 2 Ultimately, it shows that conventional serological methods to detect active infection in cats are not always reliable. 2 Figure 2 illustrates the possible immune response of felids to L infantum infection.

Figure 2.

Suggested immune response of felids to Leishmania species infection, in accordance with the immune mechanism in canine leishmaniosis (modified from Barbiéri 45 ). IFN-γ = interferon gamma; IL = interleukin; MCH II = major histocompatibility complex; NO = nitric oxide; P = plasma cell; Tc = cyotoxic cell; TCD4+ = T-helper cell; Th1 = type-1 T-helper cell; Th2 = type-2 T-helper cell; TGF-β = transformation growth factor beta; TNF-α = tumor necrosis factor alpha; Treg = regulatory T cell

The natural resistance of cats to leishmaniosis is widely suggested by the spontaneous healing of the lesion, which is often characterised by minimal or limited pathological changes.38,43

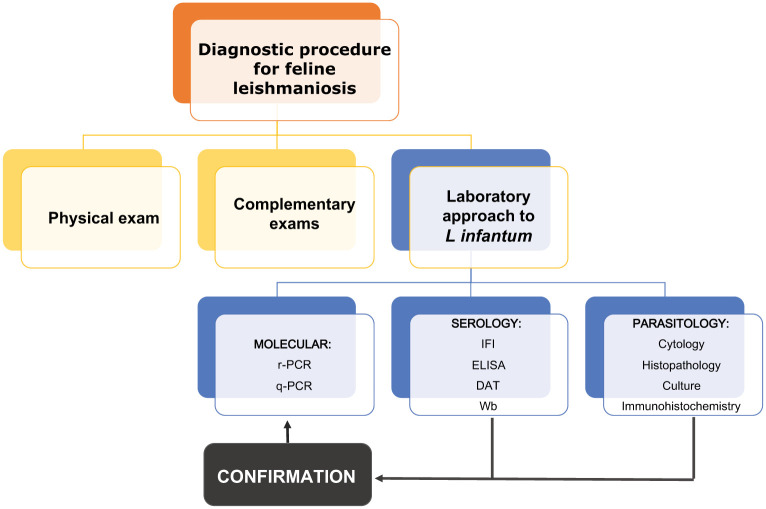

Diagnosis

Laboratory methods are essential for the diagnosis of Leishmania species infection (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Feline leishmaniosis diagnostic methodologies. DAT = direct agglutination test; IFI = indirect immunofluorescence; Wb = Western blotting

In clinically manifested visceral leishmaniosis, haemogram and biochemical analysis frequently show leukocytosis with neutrophilia, as well as urea and aspartate aminotransferase above the reference intervals. Creatinine, alanine aminotransferase and alkaline phosphatase can present normal values. 42 Neutrophilia with monocytosis and hyperglobulinaemia with polyclonal gammopathy was also reported. 32

Direct observation of the parasite might be undertaken through cytology and/or skin biopsy, namely from cutaneous lesions, lymph node or bone marrow.7,39 Cytology by aspiration or impression can be carried out in affected organs, such as the liver, spleen and kidney.8,31,46 Direct parasitological examination of the popliteal lymph node by aspiration cytology was recently demonstrated to be more sensitive compared with cytology from other organs, such as bone marrow, the spleen or liver. 39 L infantum amastigotes were also found in the cytoplasm of neutrophils in both blood and buffy coat smears (4% of the neutrophils), as well as in the splenic parenchyma and the follicular centres of lymph nodes. 31

Histopathology has an acceptable sensitivity and specificity, especially for the diagnosis of cats with cutaneous lesions. 30 Immunohistochemistry can be used as a confirmatory method 38 or as first-line diagnosis. 19

The culture of Leishmania species promastigotes is an additional direct method, but it has some disadvantages, as it features low sensitivity and is time-consuming, taking too long to obtain results. 30 Although blood, bone marrow or lymph node samples can be used, some authors consider that blood is not a suitably sensitive specimen for culture in cats because of the low parasitaemia and small amount collected, resulting in lower sensitivity of the culture method. 2

The established higher sensitivity of molecular techniques such as PCR, which further allows the confirmation of L infantum,1,11,47 makes this a good option to confirm the diagnosis and for detection in asymptomatic animals. 37 However, the detection of DNA of L infantum may not necessarily mean the existence of an active infection. In addition, it has been shown that afterwards, kinetoplast and nuclear parasite DNA degradation occurs very rapidly. 48 In dogs, the most suitable method to detect the DNA of Leishmania species is a lymph node biopsy. 10

One of the most important serological techniques is indirect immunofluorescence (IFI) assay, also known as the indirect fluorescence antibody test (IFAT). The IFI cut-off titre can be set at 1:80 for cats, as in dogs, following the work of Pennisi et al 49 carried out with positive and negative controls. Nevertheless, further studies are needed to confirm the best cut-off value for this technique to discriminate between positive and negative samples. Although IFI is considered the reference technique for CaL and human leishmaniosis (HuL) diagnosis, 23 for FeL diagnosis results should be interpreted together with other diagnostic methods and clinical signs.17,50 Low antibody titres or even seronegativity could be the result of the potentially predominant cellular immune response in cats, ultimately revealed as low seroprevalence in FeL surveys.10,31 The use of cut-off antibody titres derived from CaL can further explain such low seroprevalence.17,28 Antigenic changes after multiple in vitro culture passages of promastigotes used in the IFAT technique were also described, which could explain some variability in antibody titres reported. 51,52

Other serological techniques include ELISA and Western blotting, which have been recently modified by the use of a molecular specific marker that is highly immunogenic, named superoxide dismutase of iron (Fe-SOD). 17

Therapy and prevention strategies

Information about therapeutic efficacy in FeL cases is scarce, with few investigated cases; the majority of the anti-leishmanial drugs have been studied just for dogs. Even for dogs, some of the studied and licensed treatment options are not considered to be capable of a complete cure. 1 Moreover, the strain of L infantum defines the host’s clinical manifestation, as it can modulate susceptibility or determine resistance to one drug. 52

Naturally infected cats do not seem to recover without specific anti-leishmanial therapy. 26 However, a 12 month monitoring study in Spain reported that 11/27 cats (with FeL diagnosed by IFI and/or PCR) had good clinical status without any treatment for Leishmania species. 2

Pentamidine, administrated intramuscularly at the same dose recommended for dogs, allowed a cat to be clinically cured. 34 Nevertheless, allopurinol is the therapy recommended by the European Advisory Board on Cat Diseases (ABCD), at a dosage of 10–20 mg/kg q24h or q12h. 47 A positive clinical response in two cats treated with allopurinol (a 7-year-old with blepharitis and a 14-year-old with conjunctivitis, respectively, both with raised parasitic load) was described. 38 Allopurinol, 100 mg q24h, was also administered to a 14-year-old FIV-positive cat with a 3 year history of recurrent pododermatitis. 30 After 4 months of treatment, this case of disseminated leishmaniosis was considered to be in remission, with healing of the dermal lesions. The treatment further contributed to a reduction in the parasitaemia (11 parasites/ml in contrast with 26 parasites/ml at the point of diagnosis). The cat died 3 months later in a traffic accident. The post-mortem examination revealed development of adipose tissue reservoirs, suggesting improvement of its clinical condition. PCR confirmed the presence of parasites in the circulating blood.

A combination of meglumine antimoniate 5 mg/kg q24h SC with ketoconazole 10 mg/kg q24h PO was successfully administered to a cat with dermatological injuries and visceral involvement. Treatment was followed by three cycles for 4 weeks, with a 10 day interval.1,39 Treatment of L mexicana infection with clotrimazole followed by paromomycin 15% (topically) was not effective. Six months later, the cat developed a new lesion in the nasal mucosa that was managed with levamisole (1 mg/kg q48h), but without clinical success. 34

Supportive treatment is required in leishmaniosis, especially in animals with visceral compromise, such as hepatic failure and chronic kidney disease, given the hepato- and nephrotoxic potential of some drugs. Monitoring of hepatic and renal functions in cats receiving anti-leishmanial therapy is thus recommended. 53

Regression or a positive clinical response in FeL can be determined by the low number of parasites in lymphocytes and macrophages, indicating a cellular response and healing process. 38

Given the above, prevention should be the main goal. Topical insecticides prevent sandfly bites. Repellents should be used in animals that inhabit or travel to, even if only temporarily, endemic zones. 54 Pyrethrins and pyrethroids exert efficient repellent activity against phlebotomines, and thus are widely accepted and effective in CaL control. The decreased hydrolysis of the esters of pyrethroids makes cats intolerant to pyrethrins and pyrethroids. A recently commercially available pyrethroid class molecule, flumethrin, is reported as safe in cats, being effective against ticks, fleas and arthropods.55,56 Another option is imidacloprid, which according to a study carried out in Italy, when combined with flumethrin showed efficacy in the prevention of CaL in an area considered hyperendemic. 57 An additional prophylaxis measure recommended in endemic areas is the use of impregnated nets and spraying of shelters and areas occupied by human beings and animals with insecticide solutions.

Gradoni 54 further supports mandatory notification of Leishmania species in problematic regions as well as in non-endemic contiguous areas.

Conclusions

This work aims to raise awareness about FeL among veterinarians by providing a review of the current status of FeL infection caused by L infantum worldwide, the major clinicopathological features of infection, along with recent developments on FeL diagnosis, treatment and prevention.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Escola Universitaria Vasco da Gama, Coimbra, Portugal.

Footnotes

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

None of the authors of this paper has a commercial, financial or personal relationship with other people or organisations that could inappropriately influence or bias the content of the paper.

Accepted: 6 May 2015

References

- 1. Solano-Gallego L, Baneth G. Feline leishmaniosis. In: Greene CE. (ed). Infectious diseases of the dog and cat. 4th ed. St Louis, MO: Elsevier, 2006, pp 748–749. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Martín-Sánchez J, Acedo C, Muñoz-Pérez M, et al. Infection by Leishmania infantum in cats: epidemiological study in Spain. Vet Parasitol 2007; 145: 267–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Trainor KE, Porter BF, Logan KS, et al. Eight cases of feline cutaneous leishmaniosis in Texas. Vet Pathol 2010; 47: 1076–1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bonfante-Garrido R, Valdivia O, Torrealba J, et al. Cutaneous leishmaniosis in cats (Felis domesticus) caused by Leishmania venezuelensis. FCV-LUZ 1996; 13: 187–190. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schubach TMP, Figueiredo FB, Pereira SA, et al. American cutaneous leishmaniasis in two cats from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: first report of natural infection with Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2004; 98: 165–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rougeron V, Catzeflis F, Hide M, et al. First clinical case of cutaneous leishmaniasis due to Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis in a domestic cat from French Guiana. Vet Parasitol 2011; 181: 325–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ozon C, Marty P, Pratlong F. Disseminated feline leishmaniosis due to Leishmania infantum in Southern France. Vet Parasitol 1998; 75: 273–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Grevot A, Jaussaud H, Marty P, et al. Leishmaniosis due to Leishmania infantum in a FIV and FeLV positive cat with squamous cell carcinoma diagnosed with histological, serological and isoenzymatic methods. Parasite J 2005; 12: 271–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cardoso L, Lopes AP, Sherry K, et al. Low seroprevalence of Leishmania infantum infection in cats from northern Portugal based on DAT and ELISA. Vet Parasitol 2010: 174; 37–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Maia C, Gomes J, Cristovão J, et al. Feline leishmania infection in a canine leishmaniosis endemic region, Portugal. Vet Parasitol 2010; 174: 336–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gramiccia M. Recent advances in leishmaniosis in pet animals: epidemiology, diagnostics and anti-vectorial prophylaxis. Vet Parasitol 2011; 181: 23–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Afonso MO, Alves-Pires C. Bioecologia dos vectores. In: Santos-Gomes G, Fonseca IP. (eds). Leishmaniose canina. Lisbon: Merial, 2008, pp 27–39. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Simões-Mattos L, Bevilaqua C, Mattos M, et al. Feline leishmaniosis: uncommon or unknown? Rev Port Ciências Vet 2004; 550: 79–87. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sergent E, Sergent E, Lombard J, et al. La leishmaniose à Alger. Infection simultanée d’un enfant, d’un chien et d’un chat dans la même habitation. Bull Soc Pathol Exot 1912; 5: 93–98. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Maia C, Afonso MO, Neto L, et al. Molecular detection of Leishmania infantum in naturally infected Phlebotomus perniciosus from Algarve region, Portugal. J Vector Borne Dis 2009; 46: 268–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sobrinho LS, Rossi CN, Vides JP, et al. Coinfection of Leishmania chagasi with Toxoplasma gondii, feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) and feline leukemia virus (FeLV) in cats from an endemic area of zoonotic visceral leishmaniosis. Vet Parasitol 2012; 187: 302–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Longoni S, López-Cespedes A, Sánchez-Moreno M, et al. Detection of different Leishmania spp. and Trypanossoma cruzi antibodies in cats from the Yucatan Peninsula (Mexico) using an iron superoxide dismutase excreted as antigen. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis 2012; 35: 469–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Velázquez A, Medina M, Pedrozo R, et al. Prevalencia de anticuerpos anti-Leishmania infantum por immunofluorescencia indirecta (IFI) y estudio de factores de riesgo en gatos domésticos en el Paraguay. Vet Zootecn 2011; 18: 284–296. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Vides JP, Schwardt TF, Sobrinho LS, et al. Leishmania chagasi infection in cats with dermatologic lesions from an endemic area of visceral leishmaniosis in Brazil. Vet Parasitol 2011; 178: 22–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mosallanejad B, Avizeh R, Razi Jalali MH, et al. Antibody detection against Leishmania infantum in sera of companion cats in Ahvaz, south west of Iran. Arch Razi Instit 2013; 2: 165–171. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Diakou A, Papadopoulos E, Lazarides K. Specific anti-Leishmania spp. antibodies in stray cats in Greece. J Feline Med Surg 2009; 11: 728–730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nasereddin A, Salant H, Abdeen Z. Feline leishmaniosis in Jerusalem: serological investigation. Vet Parasitol 2008; 158: 364–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Maia C, Nunes M, Campino L. Importance of cats in zoonotic leishmaniosis in Portugal. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2008; 8: 555–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Vita S, Santori D, Aguzzi I, et al. Feline leishmaniosis and ehrlichiosis: serological investigation in Abruzzo region. Vet Res Commun 2005; 29: 319–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Poli A, Abramo F, Barsotti P, et al. Feline leishmaniosis due to Leishmania infantum in Italy. Vet Parasitol 2002; 106: 181–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Solano-Gallego L, Rodriguez-Cortes A, Iniesta L, et al. Cross-sectional serosurvey of feline leishmaniosis in ecoregions around the Northwestern Mediterranean. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2007; 76: 676–680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. da Silva AV, de Souza Cândido CD, de Pita Pereira D, et al. The first record of American visceral leishmaniosis in domestic cats from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Acta Tropica 2008; 105; 92–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Maroli M, Pennisi MG, Di Muccio T, et al. Infection of sandflies by a cat naturally infected with Leishmania infantum. Vet Parasitol 2007; 145: 357–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Quinnell RJ, Courtenay O. Transmission, reservoir hosts and control of zoonotic visceral leishmaniosis. Parasitology 2009; 136: 1915–1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pocholle E, Reyes-Gomez E, Giacomo A, et al. Un cas de leishmaniose féline disséminée dans le sud de la France. Parasite 2012; 19: 77–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Marcos R, Santos M, Malhão F, et al. Pancytopenia in a cat with visceral leishmaniosis. Vet Clin Pathol 2009; 38: 201–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Leiva M, Lloret A, Peña T, et al. Therapy of ocular leishmaniosis in a cat. Vet Ophthalmol 2005; 1: 71–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Savani ES, de Oliveira Camargo MC, de Carvalho, et al. The first record in the Americas of an autochthonous case of Leishmania infantum (chagasi) in a domestic cat (Felix catus) from Cotia County, Sao Paulo State, Brazil. Vet Parasitol 2004; 120: 229–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pennisi G. A high prevalence of feline leishmaniosis in southern Italy. Intervet Proceedings of the 2nd International Canine Leishmaniosis Forum; 2002 Feb 6–9; Seville, Spain. Boxmeer: Intervet, 2002, pp 39–48. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hervás J, De Lara F, Sánchez-Isarria M, et al. Two cases of feline visceral and cutaneous leishmaniosis in Spain. J Feline Med Surg 1999; 1: 101–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Soares CSA, Duarte SC, Sousa SR. The cat as an integrating host in the epidemiology of Leishmania infantum. Acta Parasitol Port 2014; 20: 41–46. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gramiccia M, Gradoni L. The current status of zoonotic leishmaniases and approaches to disease control. Int J Parasitol 2005; 35: 1169–1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Navarro JA, Sánchez J, Peñafiel-Verdú C, et al. Histopathological lesions in 15 cats with leishmaniosis. J Comp Pathol 2010; 143: 297–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Costa T, Rossi C, Laurenti M, et al. Ocorrência de Leishmaniose em gatos de área endémica para leishmaniose visceral. Braz J Vet Res Animal Sci 2010; 3: 213–217. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bourdoiseau G. Leishmaniose féline: actualités. Prat Med Chirurg Animal Comp 2011; 46: 23–26. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Coelho WM, do Amarante AF, Apolinario C, et al. Seroepidemiology of Toxoplasma gondii, Neospora caninum, and Leishmania spp. infections and risk factors for cats from Brazil. Parasitol Res 2011; 109: 1009–1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. da Silva SM, Rabelo PF, Gontijo Nde F, et al. First report of infection of Lutzomyia longipalpis by Leishmania (Leishmania) infantum from a naturally infected cat of Brazil. Vet Parasitol 2010; 174: 150–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Simões-Mattos L, Mattos MR, Teixeira MJ, et al. The susceptibility of domestic cats (Felis catus) to experimental infection with Leishmania braziliensis. Vet Parasitol 2005; 127; 199–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sherry K, Miró G, Trotta M, et al. A serological and molecular study of Leishmania infantum infection in cats from the Island of Ibiza (Spain). Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2011; 11: 239–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Barbiéri CL. Immunology of canine leishmaniosis. Parasite Immunol 2006; 28: 329–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bresciani K, Serrano A, de Matos L, et al. Ocorrência de Leishmania spp em felinos do municipio de Araçatuba. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 2010; 19: 127–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Pennisi M, Hartmann K, Lloret M, et al. Leishmaniosis in cats: ABCD guidelines on prevention and management. J Feline Med Surg 2013; 13: 638–642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Prina E, Roux E, Mattei D, et al. Leishmania DNA is rapidly degraded following parasite death: an analysis by microscopy and real time PCR. Microb Infect 2007; 9: 1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Pennisi MG, Lupo T, Malara D, et al. Serological and molecular prevalence of Leishmania infantum infection in cats from Southern Italy [abstract]. J Feline Med Surg 2012; 14: 656. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Spada E, Proverbio D, Migliazzo A, et al. Serological and molecular evaluation of Leishmania infantum infection in stray cats in a nonendemic area in northern Italy. Parasitol 2013; 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Moreno I, Álvarez J, Garcia N, et al. Detection of anti-Leishmania infantum antibodies in sylvatic lagomorphs from an epidemic area of Madrid using the indirect immunofluorescence antibody test. Vet Parasitol 2014; 199: 264–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Aït-Oudhia K, Gazanion E, Sereno D, et al. In vitro susceptibility to antimonials and amphotericin B of Leishmania infantum strains isolated from dogs in a region lacking drug selection pressure. Vet Parasitol 2012; 187: 386–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Solano-Gallego, Cardoso L. Epidemiologia en Europa. In: Saz S, Esteve LO, Esteve LO, et al. (eds). Leishmaniose: una revisión actualizada. 1st ed. Navarra: Servet editoral, 2013, pp 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Gradoni L. Epidemiological surveillance of leishmaniosis in the European Union: operational and research challenges. Eurosurv 2013; 18: 2–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Stanneck D, Rass J, Radeloff I, et al. Evaluation of the long-term efficacy and safety of an imidacloprid 10%/flumethrin 4.5% polymer matrix collar (Seresto) in dogs and cats naturally infested with fleas and/or ticks in multicentre clinical field studies in Europe. Parasites Vectors 2012; 5: 66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Stanneck D, Kruedewagen E, Fourle J, et al. Efficacy of an imidacloprid/flumethrin collar against fleas and ticks on cats. Parasites Vectors 2012; 5: 82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Otranto D, Dantas-Torres F, de Caprariis, et al. Prevention of canine leishmaniosis in a hyper-endemic area using a combination of 10% imidacloprid/4.5% flumethrin. PloS One 2013; 8: 56374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]