Abstract

Knowledge of the structures formed by proteins and small ligands is of fundamental importance for understanding molecular principles of chemotherapy and for designing new and more effective drugs. Due to the still high costs and to the several limitations of experimental techniques, it is most often desirable to predict these ligand-protein complexes in silico, particularly when screening for new putative drugs from databases of millions of compounds. While virtual screening based on molecular docking is widely used for this purpose, it generally fails in mimicking binding events associated with large conformational changes in the protein, particularly when the latter involve multiple domains. In this work, we describe a new methodology aimed at generating bound-like conformations of very flexible and allosteric proteins bearing multiple binding sites. Validation was performed on the enzyme adenylate kinase (ADK), a paradigmatic example of proteins that undergo very large conformational changes upon ligand binding. By only exploiting the unbound structure and the putative binding sites of the protein, we generated a significant fraction of bound-like structures, which employed in ensemble-docking calculations allowed to find native-like poses of substrates, inhibitors, and catalytically incompetent binders. Our protocol provides a general framework for the generation of bound-like conformations of flexible proteins that are suitable to host different ligands, demonstrating high sensitivity to the fine chemical details that regulate protein’s activity. We foresee applications in virtual screening for difficult targets, prediction of the impact of amino acid mutations on structure and dynamics, and protein engineering.

Introduction

Molecular recognition is a fundamental process for cellular life, regulation, and pathology,1,2 yet its quantitative understanding remains a major challenge due to the complexity of accounting for interactions among flexible partners fluttering in a crowded solution. In fact, the structural determinants of molecular recognition are best described considering an ensemble of conformational states of each (macro)molecule involved.2,3 This is particularly critical for proteins, which represent the majority of interactors and span a very wide flexibility range (from side-chain reorientations to large-scale domain motions, possibly coupled to secondary structure variations).2 The adaptability of targets is crucial in accommodating various ligands that establish diverse binding interactions, especially for multi-specific proteins, whereby even minor conformational changes can enable the binding of multiple compounds to different regions of the same broad binding site.4–6

The rapid increase in the number of experimentally resolved protein structures has fueled in the last decades the development of a large variety of computational tools to mine their conformational space, including machine/deep-learning approaches integrating experimental data and simulations.7–26 Methods to mimic protein-ligand association in silico, such as molecular docking and virtual screening, have become routinary ingredients in any modern drug design lab.2,27,28 Among possible applications a key one concerns the prediction of the interactions between proteins and small molecules (ligands), which underlies chemotherapy and drug design.2,29,30 Despite its widespread use, the accurate description of partners’ flexibility in molecular docking remains a big challenge in the field, significantly affecting accuracy.2,27,29,31 This is mainly due to the difficulties in exploring plasticity in high-dimensional spaces, coupled to the notorious sensitivity of molecular docking to even minor structural changes at the binding interface.2 These difficulties affect also AI-based algorithms, particularly for the generation of protein dynamical ensembles of high conformational diversity or in the presence of interactions with membranes,32 although the recently published algorithm NeuralPlexer achieved an accuracy comparable to state-of-the-art methods in reproducing protein-ligand structures.33

Among the strategies developed to cope with the flexibility issue,29 ensemble-docking accounts for plasticity by using a pre-defined set of structures of one (generally the protein) or both the binding partners.27,34,35 The method has been successfully applied to various targets, showcasing its versatility in drug discovery efforts.30,36–39 Within this framework, we recently proposed EDES (Ensemble Docking with Enhanced sampling of pocket Shape),40–42 a method employing metadynamics simulations43–47 with a set of ad hoc collective variables to bias the shape and the volume of a binding site. EDES was validated on a set of non-allosteric globular proteins bearing a single binding site, enabling the prediction of their bound(holo)-like conformations. Here we largely re-designed the original protocol, hereafter referred as generalized EDES (gEDES), in order to deal with multi-domain allosteric proteins bearing extended binding sites composed of multiple (sub)pockets. These proteins include indisputably relevant targets for drug design efforts.48,49

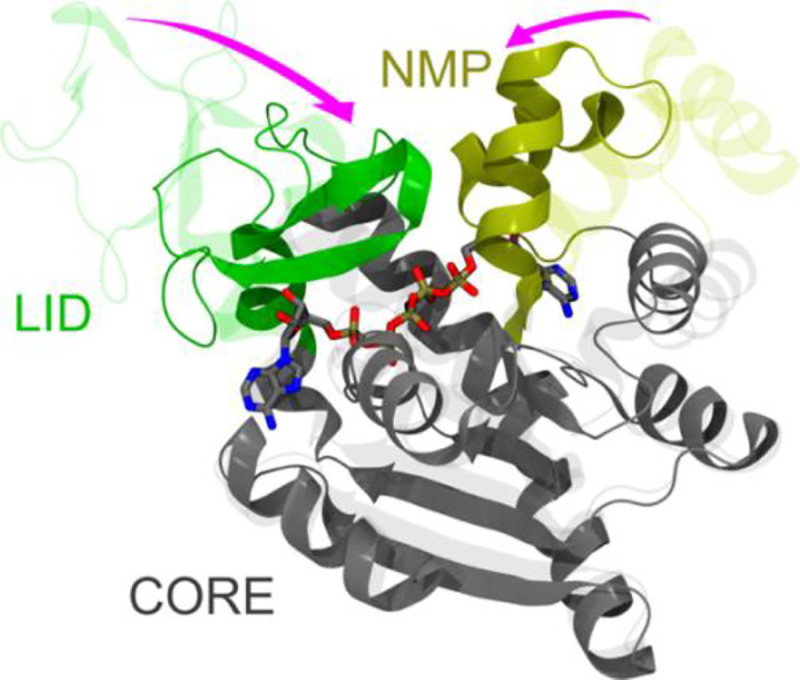

We validated gEDES on the pharmaceutically relevant enzyme adenylate kinase (ADK), a paradigm protein undergoing very large structural rearrangements upon binding of multiple substrates to an extended region composed of two (sub)pockets (Figure 1).50,51 Structurally, ADK is as a monomeric enzyme composed of a main domain (CORE) linked to a NMP-binding (NMP) and an ATP-binding (LID) domain.50 These three domains embed two distinct binding regions at the interfaces between the CORE and the NMP and the LID regions (hereafter NC and LC respectively in Figure 1), which bind ATP and AMP (substrates for the phosphoryl transfer) or two ADP molecules during the reverse reaction. During the catalytic cycle, the NMP and LID domains close over the substrate(s) via hinge-like motions (pink arrows in Figure 1),52–54 generating a reactive environment shielded from non-structural water molecules.55,56 This behavior is shared by different classes of pharmaceutically relevant proteins, including kinases and transferases.57,58 Allosteric models of ADK activity have been proposed on the basis of the high correlation between the structural rearrangements of the LC and NC interfaces.59–61 While cofactors such as Mg2+ are essential for the catalysis,62,63 substrate binding and related conformational changes are believed to be largely independent of their presence.62,64

Figure 1.

Comparison between the apo (PDB ID: 4AKE) and holo (PDB ID: 1AKE) experimental structures of ADK, represented by transparent and solid ribbons respectively. The protein structure is built upon three quasi-rigid domains, called CORE, LID and NMP, and it features two distinct binding sites. The LID (residues 118–160) and NMP (residues 30–61), which undergo hinge-like motions upon binding of substrates or inhibitors, are colored green and yellow, respectively. The CORE domain (residues 1–29, 62–117, 161–214) is colored gray. AP5 is shown by sticks colored by atom type (C, O, N, P atoms in grey, red, blue, and tan, respectively). The main hinge-like conformational changes between adjacent quasi-rigid domains are highlighted by the pink arrows.

Due to its peculiarities, ADK has been the subject of several experimental64–68 and computational59,69–84 studies shedding light on the details of the structural rearrangements and the energetics governing its biological activity. Moreover, ADK has been extensively employed as paradigm system to benchmark various computational strategies aiming to reproduce large/allosteric apo(open)/holo(closed) conformational transitions,71,72,76–79,85–90 as well as the ability of the predicted structures to correctly reproduce the binding of substrates and inhibitors in molecular docking calculations.81,91

Here, we demonstrate that our new protocol can generate a significant fraction of structures of ADK that are very similar to those bound to a set of different ligands, without exploiting any information about these compounds. Importantly: i) the ligands include substrates and inhibitors bound to a closed (active) conformation of the enzyme, as well as an incompetent binder bound to an open (inactive) state; ii) the agreement encompasses the fine geometry of the extended binding region, resulting in the correct side-chain orientation of most residues therein. Moreover, when employed in ensemble-docking calculations, these conformations: i) yielded native-like poses of substrates and inhibitors of ADK among the top-ranked ones for all the ligands; ii) reproduced the binding mode of the catalytically inactive GTP analog to an open structure of ADK. These results point to the high accuracy of gEDES in accounting for the fine chemical details regulating the activity of this enzyme, a feature that AI-based methods could not easily catch. In summary, gEDES stands among the state-of-the-art tools for accurate in silico Structure-Based Drug Design.

Materials and Methods

Binding site determination

The binding region of ADK was identified from the apo structure via the freely available site-finder software COACH-D.92 In line with previous literature,64,75 we selected the structure with PDB ID 4AKE,93 resolved at 2.2 Å resolution and devoid of any missing residue. COACH-D gives in output a set of up to 10 putative binding sites, together with a ranking score C ranging from 0 to 1, where a higher score indicates a more reliable prediction. In the case of ADK, the software identified three binding regions (Table S1) displaying a C-score respectively of 0.99 (BS1COACH), 0.89 (BS2COACH), and 0.67 (BS3COACH), while the remaining predictions featured very low C-scores (<0.01) and as such were discarded. For our purposes, we identified a consensus binding region (hereafter BSCOACH) by merging all the residues belonging to the three relevant sites mentioned above. Importantly, this choice avoids bias towards any ligand-specific binding site.

To test the accuracy of our protocol in reproducing the conformation of different experimental binding sites of ADK, we selected four complex structures, each bearing a different ligand and displaying full sequence identity to that of the apo protein. The PDB IDs of these complexes are 1AKE,94 2ECK,95 1ANK,55 and 6F7U.64 In 1AKE, the protein was resolved in complex with the inhibitor P1,P5-bis(adenosine-5’-)pentaphosphate (hereafter AP5, see Figure 1), mimicking the presence of two physiological substrates and binding across the LC and NC interfaces. In 1ANK the protein was complexed with AMP, a physiological substrate, and with ANP, a non-hydrolysable ATP analog, while in 2ECK ADK bore two physiological substrates, namely ADP and AMP. The non-hydrolysable (and thus catalytically incompetent) GTP analog β,γ-methyleneguanosine 5′-triphosphate (herafter GCP) was bound to the LC interface of the protein in the 6F7U structure, which resembles closely the open (unbound) ADK structure. This latter system allows for benchmarking the protocol against the impact of subtle chemical details on the conformation of the complexes. Four different experimental binding regions, labeled BSAP5, BSGCP, BSADP, and BSAMP, were defined by taking all the residues within 3.5 Å from the corresponding ligands AP5, GCP, ADP, and AMP in the structures identified by PDB IDs 1AKE, 6F7U, 2ECK, and 1ANK respectively (Table S1). BSAP5 spans both the NC and LC interfaces, while BSGCP and BSADP identify two slightly different regions across the LC interface, and BSAMP is located within the NC interface. Note that while enhanced conformational sampling will be performed by biasing BSCOACH, the sampling performance (that is the ability of gEDES in reproducing ADK bound-like conformations) will be assessed with respect to the experimental binding regions, which are truly relevant to ligand binding.

Standard MD

Standard all-atom MD simulations of the apo protein (hereafter MDstd) embedded in a 0.15 KCl water solution (~46.000 atoms in total) were carried out using the pmemd module of the AMBER20 package.96 The initial distance between the protein and the edge of the box was set to be at least 16 Å in each direction.

The topology file was created using the LEaP module of AmberTools21 starting from the apo structure. The AMBER-14SB97 force field was used for the protein, the TIP3P98 model was used for water, and the parameters for the ions were obtained from Wang et al.99 Long-range electrostatics was evaluated through the particle-mesh Ewald algorithm using a real-space cutoff of 12 Å and a grid spacing of 1 Å in each dimension. The van der Waals interactions were treated by a Lennard-Jones potential using a smooth cutoff (switching radius 10 Å, cutoff radius 12 Å). Multistep energy minimization with a combination of the steepest-descent and conjugate-gradient methods was carried out to relax the internal constraints of the systems by gradually releasing positional restraints. Next, the system was heated from 0 to 310 K in 10 ns of constant-pressure heating (NPT) MD simulation using the Langevin thermostat (collision frequency of 1 ps−1) and the Berendsen barostat. After equilibration, four production runs of 2.5 μs each were performed, for a total of 10 μs. Time steps of 2 and 4 fs (after hydrogen mass repartitioning) were used respectively for pre-production and equilibrium NPT MD simulations. Coordinates from production trajectory were saved every 100 ps.

Enhanced sampling MD

Bias-exchange well-tempered metadynamics simulations44,45 were performed on the apo protein, biasing a set of ad-hoc collective variables (CVs) able to act on both the shape and the volume of the binding pocket. We used the GROMACS 2022.4 package101 and the PLUMED 2.8 plugin.102 AMBER parameters were ported to GROMACS using the acpype parser.103 According to the original implementation of the method,40 we defined four CVs considering the residues lining BSCOACH: i) the radius of gyration (hereafter RoGBS) calculated using the gyration built-in function of PLUMED; ii) the number of (pseudo)contacts across three orthogonal “inertia planes” (CIPs), calculated through a switching function implemented in the coordination keyword of PLUMED. The “inertia planes” are defined as the planes orthogonal to the three principal inertia axes of the binding site and passing through its geometrical center. All non-hydrogenous atoms were considered to define the three CIPs, while only backbone atoms were used for RoGBS, in line with the variant of the original protocol introduced in ref. 41.

Starting from the last conformation sampled along the pre-production step of the unbiased MD, each replica was simulated without restraints for the first 10 ns. Next, an upper restraint centered at the value of RoGX-rayapo was imposed with a force constant increasing linearly from 10 to 25 kcal mol−1Å−2 in 40 ns. This preliminary phase is needed to push the system towards a structure featuring a RoGBS value close to RoGX-rayapo. Subsequently, the center of the RoGBS restraint was decreased linearly (every ns) to a value corresponding to 85% of RoGX-rayapo in 400 ns (moving restraints were applied on this CV - Figure S1). Focusing on conformations featuring collapsed sites is based on the evidence that the binding of ligands to enzymes is most often associated with such structural changes. Nonetheless, the relatively soft upper restraints adopted here still allow the sampling of structures with a larger RoGBS with respect to the value at which the restraint is set (Figure S1). After reaching the desired value, the RoGBS restraint is kept active for further 100 ns. Thus, the cumulative simulation time of each replica amounts to 550 ns.

To expand the use of our protocol for allosteric proteins bearing multiple binding sites, we employed computational algorithms (namely, SPECTRUS104) to identify the putative quasi-rigid domains of ADK. This analysis confirmed the dissection of the protein into three quasi-rigid domains, namely the CORE, LID, and NMP domains known from previous literature75,104 (Figure 1). The reliability of such subdivision was further verified by assessing, via RMSD calculations between the experimental structures, the internal conformational changes occurring upon ligand binding in each domain (Table S2). To account for hinge-like motions between the two LC and NC interfaces, we implemented the “contacts between quasi-rigid domains” (cRD) CVs representing the number of (pseudo)contacts across these interfaces. Clearly, with the aim of avoiding relying on any experimental knowledge of the binding region, we only exploited the knowledge of BSCOACH to identify residues lining the NC and LC (sub)pockets. Namely, the following procedure was adopted: i) we selected all BSCOACH residues belonging to the NMP(LID) and being within 8 Å from any residue of the CORE; ii) a second specular selection was made by taking all BSCOACH residues belonging to the CORE that are within 8 Å from any residue of the NMP(LID). This cutoff was chosen to ensure that none of the BSCOACH residues got associated with more than one cRD CV and that each list contained a minimum of 4 residues belonging to each quasi-rigid domain (limiting the onset of large structural distortions within secondary structure elements). The union of selections i) and ii) defined the cumulative list of residues used to setup the cRDLC(NC) CV (Figure 2); iii) the residues associated with the NC and LC (sub)pockets were split into two lists via domain assignment, for which the number of (pseudo)contacts was calculated via the coordination keyword of PLUMED. Furthermore, within each subpocket, the charged amino acids were separated from the others; this splitting in two CVs (cRDNC(LC)c and cRDNC(LC)o) specifically enhances the conformational sampling of charged amino acids in targets, such as ADK, which contain many of them within the BS.

Figure 2.

gEDES workflow. After choosing a structural template of the apo structure of the protein (1) either from experiments or modelling, a list of putative binding site(s) and quasi-rigid (QR) domains linked by flexible hinges is identified by exploiting experimental information or computational algorithms such as COACH-D. (2). Next, the collective variables (CVs) are setup (3): in addition to the gyration radius (RoGBS) and the three contacts across inertia planes (CIP1–3), a set of “contacts between quasi-Rigid Domains” (cRD) is also defined between residues belonging to adjacent QR domains and to the BS (namely the LID-CORE and NMP-CORE interfaces – hereafter LC and NC, respectively; see Materials and Methods for implementation details). If, as for ADK, a relevant fraction of residues lining the cRDs features a charged sidechain, this CV is further split into two new ones containing, respectively, only the charged residues and all the remaining ones. Finally, a multi-step cluster analysis is performed (4) on the trajectory generated with the gEDES setup, producing several structure representatives to be employed in ensemble docking calculations (5).

To facilitate the general applicability of the method, we automatized the workflow so that the latter cRD subdivision occurs only if: i) the binding site presents more than the 25% of charged residues and ii) each residue group defining a cRD variable is composed of at least 2 non-adjacent residues. In this case, 11 out of the 32 residues (~34 %) composing BSCOACH are charged, so this subdivision was applied.

The height w of the Gaussian hills was set to 0.6 kcal/mol, while their widths were set as reported in Table S3 based on the fluctuations recorded during a short (~200 ps) unbiased MD run. The bias factor for well-tempered metadynamics was set to 10. Hills were added every 2.5 ps, while the bias-exchange frequency was set to 50 ps. Further details on CV definitions are reported in Table S3. Coordinates of the system were saved every 10 ps.

Cluster analysis

The cluster analysis was performed in the CVs space (for both the gEDES and the unbiased runs) using in-house scripts in the R language. The distribution of RoGBS values sampled during the MD simulation was binned into 30 equally wide slices, and the built-in hclust module of R was used to perform a hierarchical agglomerative clustering within each slice, setting the number of generated clusters in the slice to , where , and are respectively the number of structures within the slice, the total number of structures, and the total number of clusters. In our case, was set to 100, and we imposed the additional requirement to have at least two clusters within each of the 30 slices. This was implemented by iteratively increasing by 10 units until the number of clusters within each of the RoGBS slices was equal or higher than two. The resulting clusters were used as starting points to perform a second cluster analysis with the K-means method (maximum number of iterations set to 10000) and generating the same number of clusters. This multistep strategy of clustering in the CV space outperforms more standard RMSD-based approaches in generating maximally diverse ensemble of protein conformations. This approach resulted respectively in 130 and 160 clusters for the gEDES and unbiased runs.

Docking

Docking was performed with the software HADDOCK105 and AutoDock.106 Ligand conformations were extracted from the relative complex structures and prepared according to the standard procedure of each software. Importantly, docking calculations, were performed on the predicted binding site (BSCOACH) independently from the ligand and thus from its true binding pocket. Thus, ligands binding to the NC(LC) interface could in principle sample the LC(NC) one.

In HADDOCK, a single docking run was performed per case, starting from the various ensembles of Nc conformations, with increased sampling (50000/1000/1000 models for it0, it1 and wat steps, respectively referring to rigid-body docking, semiflexible and final refinement in explicit solvent) using the HADDOCK2.4 web server.107 This increased sampling compared to the default was chosen in order to ensure that each conformation in the ensemble is sampled sufficiently. During it0 the protein BS residues were defined as “active”, effectively drawing the rigid ligand into the BS without restraining its orientation. For the subsequent stages only the ligand was active, improving its exploration of the binding site while maintaining at least one contact with its interacting residues. In addition, a fake bead was placed in the center of each binding site pocket and an ambiguous 0 Å distance restrain was defined to those two beads such as a ligand atom (any atom) should overlap with one of those two beads.

Those two beads were defined as “shape” in the server and have no interactions with the remaining of the system except for the defined distance restraints. All conformations in the MD ensemble were aligned on the initial apo structure and their position, together with that of the fake beads, was kept fixed during the rigid-body phase of the docking.

In AutoDock, each ligand conformation was rigidly docked on each one of the desired protein structures using the Lamarckian Genetic Algorithm (LGA). The number of energy evaluations (ga_num_evals parameter) was increased 10 times from its default value (1) to avoid repeating each calculation several times to obtain converged results. An adaptive grid was used, enclosing all the residues belonging to the BS in each different protein conformation. Finally, an additional step consisting in the relaxation of the docking poses by means of a restrained structural optimization was performed with AMBER20.96 Systems were relaxed in vacuum by means of up to 1000 cycles of steepest descent optimization followed by up to 24000 cycles using the conjugate gradients algorithm. Harmonic forces of 0.1 kcal mol−1 Å−1 were applied on all non-hydrogenous atoms of the system. Long-range electrostatics was evaluated directly using a cutoff of 99 Å, as for the Lennard-Jones potential. The AMBER-14SB97 force field was used for the protein, while the parameters of the ligands were derived from the GAFF108 force field using the antechamber module of AmberTools. Bond-charge corrections (bcc) charges were assigned to ligand atoms following structural relaxation under the “Austin Model 1 (AM1)” approximation. After this step, poses were scored according to AutoDock’s energy function. Next, the top poses (in total Nc, one for each docking run performed on a different receptor structure) were clustered using the cpptraj module of AmberTools with a hierarchical agglomerative algorithm. Namely, after structural alignment of the BS for the different complex conformations, ligand poses were clustered using a distance RMSD (dRMSD) cutoff dc = 0.067·Nnh, where Nnh is the number of non-hydrogenous atoms of the ligand. This choice was made to tune the cutoff to the molecular size of each compound and resulted in cutoffs of 3.8, 1.5, 1.8, and 2.1 Å for AP5, AMP, ADP, and GCP, respectively. Finally, clusters were ordered according to the top score (lowest binding free energy) within each cluster.

Complexes’ structure prediction with NeuralPLexer

NeuralPLexer33 simulations were run giving in input as receptor and template the chain A of the apo-structure of ADK. In addition, for each ligand, the molecular structure extracted from the PDB file of the corresponding complex was given as input to the ligand keyword. All files were provided in pdb format, and the remaining parameters were set to their default values (num-steps = 40, sampler = Langevin simulated annealing). The ‘batched structure sampling’ method was employed, which produced 16 (keyword n-samples) putative structures of the corresponding protein-ligand complex. The ‘complex structure prediction’ model, specifically trained for complex structure prediction, was used as model checkpoint.

Results and discussion

The workflow of gEDES is sketched in Figure 2. We anticipate two key features of the method: i) the introduction of a new class of CVs (cRD) to specifically enhance the motions between quasi-rigid protein domains. This allows to reproduce large conformational changes in the whole protein while biasing local CVs involving only aminoacids of the putative binding site(s); ii) the enhancement of BS breathing motions (altering its shape and volume) by means of two CVs representing pseudo-contacts between charged and non-charged groups of aminoacids. This splitting allows for effective sampling of conformations of the former group (particularly of sidechains), which otherwise could be penalized by the lower free energy barriers associated with overall fluctuations of non-charged aminoacids.

In this section, we report the performance of gEDES in generating holo-like conformations of ADK, both in terms of reproducing the overall protein structure and the fine geometry of the binding sites of four ligands. After analyzing the sampling performance, we discuss how accounting for the plasticity of the protein does lead to improved docking outcomes and accounts for distinct conformations of complexes formed by ligands featuring subtle chemical differences.

Sampling of holo-like protein conformations

The performance of gEDES in generating holo-like structures of ADK is summarized in Figure 3 and Table 1. Notably, these results were obtained without using any a priori experimental knowledge of the bound conformations. The binding site biased in metadynamics (BSCOACH) does not coincide precisely with the binding site of any ligand (indeed, it is much larger than any of them but AP5), and as such it is not biased towards specific chemotypes. BSCOACH comprises 32 residues, 11 of which (almost 35 %) are charged. By inspecting RMSD distributions in the left column of Figure 3 we see that, for all BS investigated in this work, gEDES is able to generate a non-negligible fraction of holo-like structures. The same performance was not obtained with MDstd, for which, as expected, we found conformations with RMSD values lower than 2 Å only when using BSGCP as reference (corresponding to an open structure of the enzyme). This is not surprising, as the binding to all substrates but GCP is associated with a decrease of the RoG of the corresponding BS by more than 20% (Table S4).

Figure 3.

Performance of MDstd and gEDES simulations in reproducing holo-like conformations of the computationally derived (BSCOACH, first row) and of the ADK ligands’ binding sites (2nd to last rows). The left column reports the normalized frequency distributions of the RMSD values of each site calculated on the non-hydrogenous atoms with respect to the reference structure (1AKE for BSCOACH and BSAP5, 2ECK for BSADP, 1ANK for BSAMP, 6F7U for BSGCP) after alignment of the same site. Green and gray shaded areas (lines) refer to the distributions extracted from the production trajectory (cluster representatives used for docking calculations) of the unbiased and gEDES simulations, respectively. These distributions were obtained by grouping RMSD values into bins of 0.2 Å in width and interpolating the resulting distribution with cubic splines and a density of 20 points per Å. The middle column reports the frequency of holo-like conformations sampled by each residue lining the corresponding BS during the unbiased and gEDES simulations. Bars pointing upwards refer to gEDES and are colored according to the amino acid type (red: negatively charged; blue: positively charged; black: neutral), while green bars pointing downwards refer to the unbiased simulation. A holo-like conformation is counted when the RMSD of the residue (calculated on all non-hydrogenous atoms after alignment of the whole BS) is lower than the arbitrary threshold defined for each amino acid in Table S6 (and always lower than 2.5 Å). The right column reports the normalized distributions of the fraction of total (solid lines) and charged (dashed lines) residues simultaneously assuming a holo-like conformation. The best conformation from the ensemble of clusters is also reported against the corresponding reference structure. Sidechains are shown by sticks colored from white to red according to the value of the per-residue RMSD from the reference (thin black sticks), with thick sticks identifying those residues that do not sample holo-like conformations.

Table 1.

Performance of various MD simulations in reproducing holo-like conformations of the protein structures (only Cα atoms) and of the putative binding sites (all non-hydrogenous atoms) considered in this work, measured by the percentage of structures with RSMD values below 2 and 2.5 Å, respectively. Results refer to the cumulative trajectories and to cluster representatives of both the standard MD simulation (MDstd) and the gEDES approach. PDB codes of each reference holo-structure are reported in the second row. The lowest value of the RMSD is reported in parentheses. Structural alignment for RMSD calculations has been performed on the region specified in the third row of each column.

| RMSD < 2 / 2.5 Å [%] (RMSDmin) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Holo: 1AKE | Holo: 2ECK | Holo: 1ANK | Holo: 6F7U | ||||

| BSCOACH | BSAP5 | Protein (Cα) | BSADP | BSAMP | BSGCP | Protein (Cα) | |

| MDstd | 0 / 0 (3.7) | 0 / 0 (3.9) | 0 / 0 (2.9) | 0.04 / 1.9 (1.5) | 0 / 0 (3.1) | 8.5 / 23.5 (1.1) | 4.4 / 16.2 (0.9) |

| gEDES | 0.001 / 1.3 (2.0) | 0.001 / 0.7 (2.0) | 0.05 / 0.3 (1.8) | 0.01 / 0.02 (0.9) | 0 / 0.007 (2.2) | 3.2 / 19.8 (1.3) | 3.9 / 10.1 (1.0) |

| 0 / 0 (3.9) | 0 / 0 (4.0) | 0 / 0 (3.1) | 0 / 1.8 (2.1) | 0 / 0 (3.8) | 11.2 / 24.2 (1.1) | 3.1 / 16.8 (1.5) | |

| gEDESclust | 0.8 / 4.0 (2.0) | 0 / 3.8 (2.2) | 0 / 0.8 (2.1) | 2.3 / 13.6 (1.1) | 0 / 1.5 (2.2) | 1.6 / 16.7 (2.0) | 0.8 / 3.8 (2.0) |

In the following, we will discuss the sampling performance with respect to the AP5 and GCP bound structures. Indeed, the structures of ADK bound to ADP and AMP ligands (PDB IDs: 1ANK, 2ECK) featured an overall conformation very similar to the one bound to AP5 (PDB ID: 1AKE), with sub-angstrom structural variations at the corresponding BSs (Table S5).

The second column of Figure 3 illustrates the performances of gEDES and MDstd in reproducing the bound-like conformations of individual residues lining BSCOACH and all the experimental BSs. This analysis enlightens the overall superior sampling of these conformations by gEDES for residues bearing a net charge and/or an extended side chain (e.g. K13, D84, I120 for BSCOACH). In the last column of the same figure, we report the percentage of conformations displaying N amino acids simultaneously in their bound-like conformation (with N going from 0 to the number of residues lining each BS; see also Table S6). gEDES was able to generate a geometry of BSCOACH simultaneously displaying 27 out of 32 residues (of which 8 out of 11 charged amino acids) with a bound-like conformation. This in turn resulted in the accurate reproduction of bound-like conformations for all the experimental BS, which are partly overlapping and/or included in BSCOACH. In contrast, the best conformations generated from MDstd displayed less than 40% of the residues in a bound-like geometry for all binding sites but BSGCP.

Table 1 summarizes the results in terms of RMSD values from the true holo complexes for all the BSs and for the whole protein (in the case of AP5 and GCP), considering both the trajectory and cluster-derived structures. We observe that, while gEDES was able to sample conformations displaying respectively RMSD of as low as 2.0 (1.8) Å for BSCOACH and the whole protein, the best structures sampled by MDstd featured values of 3.7 and 2.9 Å respectively. These findings clearly indicate that even in absence of any bias on the whole protein, our set of local CVs was able to drag the whole structure toward holo-like geometries.

More importantly, our multi-step clustering pipeline allowed us to preserve these geometries within a restricted pool of selected structures. Indeed, the sets of conformations selected from gEDES MDs for the ensemble docking of AP5, ADP, AMP, and GCP include conformations distant respectively 2.2, 1.1, 2.2, 2.0 Å from the corresponding complex structures. As expected, gEDES and MDstd have similar sampling performances only in the case of BSGCP. These results further confirm the general applicability of gEDES, despite the protocol was originally developed to address targets undergoing large conformational changes.

Reproducing ligand native poses

In this subsection, we compare the ensemble-docking results obtained using the conformational clusters extracted from gEDES and MDstd simulations. The poses reported for AutoDock4 were obtained after performing a ligand cluster analysis on the top poses obtained from each individual docking run (i.e. a run for each protein conformation), while in HADDOCK all cluster conformations within each ensemble were used in a single docking run. Note that, in the spirit of using our protocol in the prediction of unknown behaviors, docking was performed on the region encompassing the full BSCOACH. Details of this implementation can be found in the Materials and Methods section.

Overall, for all ligands but ADP, only the conformations of ADK obtained with gEDES were able to generate a native-like complex structure ranked among the top ten poses (Table 2). Namely, using either AutoDock4 or HADDOCK with the clusters obtained from gEDES, the top two poses contain a near-native structure (RMSDlig values of 2.2 and 1.6 Å, respectively); importantly, these poses fitted within conformations of BSAP5 resembling that of the true complex, which enables recovering a large fraction Fnat of native contacts. On the other hand, clusters obtained from MDstd also yield near-native ligand poses, but these were ranked poorly and were obtained on largely distorted BS structures (RMSDBS values of 4.9 Å and 7.9 Å respectively), thus describing incorrect binding modes with low Fnat values.

Table 2.

Performance of AutoDock4 and HADDOCK in reproducing the experimental structures of the complexes between ADK and the four ligands investigated in this work. For each compound, two cluster sets (gEDES and MDstd) were employed in ensemble-docking calculations. The Autodock results refer to clusters of docking poses obtained from a cluster analysis performed on all generated complexes (see Methods) while for HADDOCK they refer to the single structures from a single run starting from the ensemble of MD conformations. The sampling performance is calculated as the percentage of poses within 2.5 Å from the native (for HADDOCK calculated at the rigid-body stage out of 50000 poses). The pose ranking refers to the first native-like conformation obtained using the highest score within each cluster. The next row reports the heavy atoms RMSD of the ligand and for the binding site calculated for the first native-like conformation following ranking. Fnat indicates the fraction of native contacts recovered within a shell of 5 Å from the ligand in the experimental structures. The overall best poses are highlighted in bold and shown in Figure 4.

| AP5 | AMP | ADP | GCP | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDstd | gEDES | MDstd | gEDES | MDstd | gEDES | MDstd | gEDES | ||

| Autodock | Sampl. perf. [%] | 0.6 | 1.8 | - | 0.9 | 1.9 | 2.7 | 1.2 | 1.8 |

| Pose rank | 19 | 2 | - | 7 | 10 | 1 | 16 | 1 | |

| RMSDlig/BS [Å] | 2.3/4.9 | 2.2/2.2 | - | 2.1/3.1 | 2.3/3.8 | 0.9/1.1 | 2.5/1.7 | 2.3/2.0 | |

| Fnat | 0.58 | 0.79 | - | 0.74 | 0.57 | 0.86 | 0.75 | 0.80 | |

| HADDOCK | Sampl. perf. [%] | 2.8 | 0.57 | - | 0.004 | 0.06 | 0.1 | 1.01 | 1.4 |

| Pose rank | 61 | 1 | 643 | 193 | 23 | 1 | 390 | 11 | |

| RMSDlig/BS [Å] | 2.2/7.9 | 1.6/2.1 | 2.4/8.5 | 1.7/2.7 | 2.3/4.2 | 0.6/1.4 | 2.0/3.5 | 1.7/2.0 | |

| Best RMSDlig [Å] / rank | 1.8/68 | 0.9/16 | 2.4/643 | 1.7/193 | 2.2/81 | 0.5/7 | 1.9/644 | 0.8/74 | |

| Fnat | 0.38 | 0.82 | 0.33 | 0.67 | 0.54 | 0.88 | 0.43 | 0.86 | |

A similar situation is seen for ADP, for which both docking programs find a native-like pose (associated with low RMSDlig and high Fnat values) ranked as first only when using gEDES clusters. On the other hand, while some native-like poses were also found when using the MDstd clusters, they were ranked poorly and (again) associated with distorted BS conformations. Regarding GCP, Autodock and HADDOCK found the native-like pose ranked as 1st and 11th respectively when using gEDES clusters, to be compared with rank 16th for AutoDock4 when using structures obtained from MDstd. In this case, as expected, near-native ligand poses were found on holo-like BSGCP conformations with both the MDstd and the gEDES clusters. Finally, gEDES retrieved a near-native ligand pose of AMP (RMSDlig = 2.1 Å), although associated with a slightly distorted binding region (RMSDBS = 3.1 Å) compared to the previous ligands.

On the other hand, no native-like pose was retrieved when using protein structures derived from MDstd. The slightly worst gEDES performance for AMP is perhaps expected, as this compound binds to the NC interface, whose competent conformation is triggered via an allosteric boost involving a previous closure of the LID domain.59 Nonetheless, binding-prone conformation of BSAMP enabling to accurately predict near-native AMP poses were recovered even without explicitly mimicking allosteric regulation.

Comparison with previous works

In this section, we compare our results with previous works aiming to explore ADK functional motions, eventually leading to the generation of druggable structures, and to characterize the energetics of its apo-to-holo transitions.

Flores and Gerstein employed ADK as test system for their “conformation explorer” algorithm,109 which was developed to sample structural rearrangements of proteins underdoing hinge-like functional motions. In the work, based on the identification of protein’s hinge axes followed by Euler rotations and MD simulations, the authors addressed only the LID motion, for which the closest-to-holo generated model displayed a Cα-RMSD (after superimposing the CORE and NMP domains) of 3.8 Å, to be compared with the value of ~17 Å (after the same superposition) between the experimental apo and holo structures.

In another work, the NMsim71 conformational search algorithm, based on elastic network models (ENM), was employed to retrieve ADK bound-like structures either by unbiased simulations or using by biasing the RoG of the protein to values below a threshold (namely, the value corresponding to the apo structure). These approaches produced respectively conformations featuring backbone RMSD as low as 3.06 Å and 2.36 Å from the holo structure.52,94

A similar methodology was employed by Ahmed et al.72 who coupled a rigid cluster normal-mode analysis (RCNMA) with the NMsim71 algorithm to generate conformations featuring a Cα-RMSD as low as 1 or 3.1 Å from the experimental complex when exploiting or not the closed structure of ADK. Unfortunately, no information was reported on the fine bound-like geometry of the BS.

Wang et al.110 employed Replica-Exchange MD simulations (starting from the holo structure) to estimate the free energy profile and the timescales associated with LID opening and closing. They found these values to be respectively ~29 μs and ~118 μs, in good correlation with the experimental data89 and pointing to the need for very long unbiased simulations to collect a statistically significant number of opening/closing events.

Yasuda et al.76 introduced a method called “parallel cascade selection MD (PaCS-MD)” to generate transition pathways from a given source structure to a target structure by repeating short-time MD simulations. Importantly, the method relies on the similarity between the principal components extracted from a set of multiple short MD simulations of a target protein and from a trajectory starting from the holo (target) geometry. Application of their approach to ADK led to models displaying a Cα-RMSD as low as 1.1 Å from the AP5-bound complex.

Jalalypour and coworkers77 developed an approach to identify key residues responsible for specific conformational transitions in proteins by comparing apo and holo structures of a generic target. Steered MD (SMD)58 simulations fed with this information were employed to trigger apo-to-holo functional rearrangements in ADK, generating conformations with Cα-RMSD as low as 3.1 Å from the AP5-bound geometry.

A thorough comparison of our method with those discussed above is limited by the lack of data regarding the accuracy in reproducing the atomistic geometry of the extended binding region considered in this work, which is relevant for drug design applications. Below, we report two examples enabling such an assessment.

In the first one, Kurkcuoglu and Doruker81 included ADK in the set of 5 proteins selected to assess the performance of their ENM-based workflow to generate an ensemble of holo-like protein conformations for docking calculations. Their best model (selected after filtering the RoG of the protein so as to discard conformations with values larger than RoGapo) displayed a Cα-RMSD of 2.4 Å over the whole protein.52,94 When these models were employed in docking calculations of AP5, the closest-to-native pose featured an RMSDlig 2.9 Å with respect to the X-ray structure with PDB ID 1AKE.

The second example regards NeuralPLexer, a recent computational approach exploiting deep learning to predict protein-ligand complex structures by integrating small molecules information and biophysical inductive bias.33 We employed this tool to reproduce the structures of the complexes between ADK and the four ligands investigated in this work, using as inputs the unbound structure of the protein and the conformations of the ligands extracted from the corresponding complexes. The results of these calculations, reported in Table 3, indicate that gEDES compares very well with NeuralPLexer. In particular, the latter package predicts complex structures that are slightly closer than those generated by gEDES and Autodock/HADDOCK for AP5 and AMP, while it has a slight worst performance for ADP and, moreover, fails in generating any native-like conformation for GCP. A recent investigation68 suggested that initial binding of AMP followed by ATP could lead to a closed state that does not allow the correct positioning of the two ligands for effective phosphate transfer. In other words, binding of AMP should occur after binding of the other substrate for optimal enzymatic activity; therefore, our results are remarkable as we did not perform any simulation of the AMT-ATP complex. Even more interesting are the results for GCP, whose binding arrests the enzyme in a catalytically non-functional open state.

Table 3.

Comparison of gEDES and NeuralPLexer performances in reproducing native-like conformations of the complexes between AK and the four ligands investigated in this work. The best pose for each ligand is highlighted by bold fonts. See caption of Table 2 for further details.

| AP5 | AMP | ADP | GCP | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autodock-gEDES | RMSDlig/BS [Å] | 2.2/2.2 (2) | 2.1/3.1 (7) | 0.9/1.1 (1) | 2.3/2.0 (1) |

| Fnat | 0.79 | 0.74 | 0.86 | 0.80 | |

| HADDOCK-gEDES | RMSDlig/BS [Å] | 1.6/2.1 (1) | 1.7/2.7 (193) | 0.6/1.4 (1) | 1.7/2.0 (11) |

| Fnat | 0.71 | 0.67 | 0.88 | 0.86 | |

| Neural PLexer | RMSDlig/BS [Å] | 1.6/1.9 (1) | 1.3/2.1 (1) | 1.0/1.8 (1) | -* |

| Fnat | 0.89 | 0.90 | 0.77 | -* | |

NeuralPLexer was unable to correctly reproduce the conformation of the protein and of the BS (minimum RMSD ~5.9 Å), as well as native-like poses of GCP (RMSDmin ~ 3.8 Å, Fnat = 0.50)

Since our approach generates several different conformations, including some open structures, we were able to retrieve native-like conformations of the complex between GCP and ADK. In contrast, NeuralPLexer generated in all cases catalitically competent structures very similar to those found for the true substrates of the enzyme. We hypothesize that this could be due, at least partly, to the large predominance of substrate bound (closed) ADK conformations.

Concluding remarks and perspectives

In silico prediction of structural determinants enabling biological and therapeutic activity by small molecules targeting proteins is a holy grail in computational biology and drug design. Accuracy and computational costs are two essential factors to be accounted for in developing software and protocols that can effectively help research in these fields. The first factor requires not only to identify the correct structures of protein-ligand complexes, but also to distinguish between active and inactive compounds based on their binding modes and affinities. This is particularly relevant when dealing with enzymes, whose selectivity comes from the fine structural and chemical matching between active sites and substrates, reducing erroneous associations.

In this work, we developed gEDES, a computational protocol for the accurate prediction of holo-like conformations of allosteric and/or multi-pocket proteins undergoing extended conformational changes upon ligand binding. Notably, gEDES relies only on the knowledge of a structure of the protein (even if unbound to any ligand) and on the identification of its putative binding site(s), thereby avoiding bias towards any specific chemotype. We validated our methodology on the paradigm enzyme adenylate kinase, widely employed to benchmark computational methods aiming to reproduce apo/holo conformational transitions and to predict holo-like conformations of proteins. gEDES was able to generate a large fraction of holo-like conformations of both the whole protein and the extended binding competent region, which is constituted by multiple distinct binding sites. Importantly, the agreement goes beyond the overall geometry of the binding region (defined by its backbone atoms) and includes the correct prediction of almost all sidechain conformations. Furthermore, these binding competent geometries were reproduced for both active and inactive protein conformations within a single simulation. When using a limited set of conformations extracted from gEDES trajectories in ensemble-docking calculations of substrates, inhibitors, and catalytically incompetent binders of adenylate kinase, we retrieved in all cases native-like structures of the complexes (which include closed and open protein conformations) ranked among the top predictions. These results demonstrate that gEDES, coupled to state-of-the-art docking simulations, is able to achieve very high sensitivity towards subtle but crucial chemical details of ligands, placing it among the state-of-the-art methodologies in the field.

In perspective, we plan to use our protocol to predict functional conformational changes in proteins, in accurate virtual screening campaigns, and in the rational design and repurposing of drugs. Exploring the conformational diversity of binding sites could lead to the identification of a larger number of promising lead candidates2,111–114 and/or to discover potential new uses for already marketed ones115. In addition, the detection of putative binding regions could in principle be improved by combining existing structural data with druggability estimations based on the physico-chemical properties of the site.22,116 Sampling could be further improved by introducing new CVs crucial for protein dynamics and/or coupling metadynamics with other enhanced-sampling methods. For example, biasing the radius of gyration of the whole protein could be of help in case of large proteins, for which exploiting only variables defined on a putative binding region could not be effective. Another possibility is the coupling of our strategy with others directly addressing the fine treatment of torsional angles117 rotations and/or secondary structure changes.118 Our workflow also allows for the inclusion of experimental information at different stages of the process, for instance during post-processing as done e.g. in refs.81 For instance, to enhance the extraction of conformations featuring a value for the radius of gyration within a desired range, the cluster analysis can be filtered accordingly. As a long-term purpose, we aim to create a database of protein structures encompassing bound, unbound, and intermediate conformational states.

Supplementary Material

Figure 4.

Best complex structures (nearest-to-native) obtained from the combined set of docking calculations using HADDOCK and AutoDock4 for all ADK ligands investigated in this work. These structures correspond to the best overall pose reported in Table 2. For each ligand (names are indicated in the figure), the top row shows the structure obtained by gEDES yielding the nearest-to-native complex geometry superposed to corresponding experimental bound conformation. These structures are shown in cartoons and colored respectively by domain (green, yellow, and gray for the LID, NMP, and CORE domains respectively) and in dark gray. The location of the ligand in the experimental structures is shown by a semi-transparent surface. The bottom row shows the comparison between the geometries of the BSs and of the ligand in the experimental bound structure vs. the nearest-to-native pose. The sidechains of residues lining the BS in the former (latter) structure are shown by dark thin (light thick) sticks colored by residue type; the ligand is shown with single color sticks in the experimental structure, while thicker sticks colored by atom type (C, N, O, P atoms in white, blue, red, and orange respectively) indicate the best docking pose.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by the Regional Government of Sardinia through the project “PROOF of CONCEPT - Valorizzazione dei risultati della ricerca in biomedicina”, and partially funded by the Italian Ministry of University and Research, PNRR, mission 4, component 2, investment 1.3 (Partenariati estesi alle università, ai centri di ricerca, alle aziende per il finanziamento di progetti di ricerca di base), title INF-ACT, project number PE00000007, CUP: F53C22000720007 (M. A., A.V.V., University of Cagliari) and by the NIAID/NIH grant no. R01AI136799 (to A.B., M. A., G.M., P.R., and A.V.V.). H.K. is a recipient of a Ph.D. fellowship co-funded by the University and Research Italian Ministry and by the company AngeliniPharma S.p.A. under the program “Programma Operativo Nazionale FSE-FESR Ricerca e Innovazione 2014–2020”, Azione I.1 “Dottorati Innovativi con caratterizzazione industriale”. A.M.J.J.B. acknowledges funding from the European Union Horizon 2020 project BioExcel (823830). We thank Vincenzo Carnevale (Temple University, Philadelphia, U.S.A.) for useful discussions and Mattia Bernetti (Istituto Italiano di Tecnologia, Italy) and Paolo Carloni (Forschungszentrum Jülich GmbH, Germany) for the careful reading of the manuscript.

References

- (1).Baron R.; McCammon J. A. Molecular Recognition and Ligand Association. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2013, 64 (1), 151–175. 10.1146/annurev-physchem-040412-110047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Du X.; Li Y.; Xia Y.-L.; Ai S.-M.; Liang J.; Sang P.; Ji X.-L.; Liu S.-Q. Insights into Protein–Ligand Interactions: Mechanisms, Models, and Methods. IJMS 2016, 17 (2), 144. 10.3390/ijms17020144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Chu W.-T.; Yan Z.; Chu X.; Zheng X.; Liu Z.; Xu L.; Zhang K.; Wang J. Physics of Biomolecular Recognition and Conformational Dynamics. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2021, 84 (12), 126601. 10.1088/1361-6633/ac3800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Ma B.; Shatsky M.; Wolfson H. J.; Nussinov R. Multiple Diverse Ligands Binding at a Single Protein Site: A Matter of Pre-existing Populations. Protein Science 2002, 11 (2), 184–197. 10.1110/ps.21302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Niitsu A.; Re S.; Oshima H.; Kamiya M.; Sugita Y. De Novo Prediction of Binders and Nonbinders for T4 Lysozyme by gREST Simulations. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2019, 59 (9), 3879–3888. 10.1021/acs.jcim.9b00416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Ahuja L. G.; Aoto P. C.; Kornev A. P.; Veglia G.; Taylor S. S. Dynamic Allostery-Based Molecular Workings of Kinase:Peptide Complexes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2019, 116 (30), 15052–15061. 10.1073/pnas.1900163116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Bonomi M.; Camilloni C.; Cavalli A.; Vendruscolo M. Metainference: A Bayesian Inference Method for Heterogeneous Systems. Sci. Adv. 2016, 2 (1), e1501177. 10.1126/sciadv.1501177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Bottaro S.; Lindorff-Larsen K. Biophysical Experiments and Biomolecular Simulations: A Perfect Match? Science 2018, 361 (6400), 355–360. 10.1126/science.aat4010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Senior A. W.; Evans R.; Jumper J.; Kirkpatrick J.; Sifre L.; Green T.; Qin C.; Žídek A.; Nelson A. W. R.; Bridgland A.; Penedones H.; Petersen S.; Simonyan K.; Crossan S.; Kohli P.; Jones D. T.; Silver D.; Kavukcuoglu K.; Hassabis D. Improved Protein Structure Prediction Using Potentials from Deep Learning. Nature 2020, 577 (7792), 706–710. 10.1038/s41586-019-1923-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Ganesan A.; Coote M. L.; Barakat K. Molecular Dynamics-Driven Drug Discovery: Leaping Forward with Confidence. Drug Discovery Today 2017, 22 (2), 249–269. 10.1016/j.drudis.2016.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Śledź P.; Caflisch A. Protein Structure-Based Drug Design: From Docking to Molecular Dynamics. Current Opinion in Structural Biology 2018, 48, 93–102. 10.1016/j.sbi.2017.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Allison J. R. Computational Methods for Exploring Protein Conformations. Biochemical Society Transactions 2020, 48 (4), 1707–1724. 10.1042/BST20200193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).De Vivo M.; Masetti M.; Bottegoni G.; Cavalli A. Role of Molecular Dynamics and Related Methods in Drug Discovery. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59 (9), 4035–4061. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Muscat S.; Stojceski F.; Danani A. Elucidating the Effect of Static Electric Field on Amyloid Beta 1–42 Supramolecular Assembly. Journal of Molecular Graphics and Modelling 2020, 96, 107535. 10.1016/j.jmgm.2020.107535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Lazim R.; Suh D.; Choi S. Advances in Molecular Dynamics Simulations and Enhanced Sampling Methods for the Study of Protein Systems. IJMS 2020, 21 (17), 6339. 10.3390/ijms21176339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Bouvier B. Curvature as a Collective Coordinate in Enhanced Sampling Membrane Simulations. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2019, 15 (12), 6551–6561. 10.1021/acs.jctc.9b00716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Souza P. C. T.; Thallmair S.; Conflitti P.; Ramírez-Palacios C.; Alessandri R.; Raniolo S.; Limongelli V.; Marrink S. J. Protein–Ligand Binding with the Coarse-Grained Martini Model. Nat Commun 2020, 11 (1), 3714. 10.1038/s41467-020-17437-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Heilmann N.; Wolf M.; Kozlowska M.; Sedghamiz E.; Setzler J.; Brieg M.; Wenzel W. Sampling of the Conformational Landscape of Small Proteins with Monte Carlo Methods. Sci Rep 2020, 10 (1), 18211. 10.1038/s41598-020-75239-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Sasmal S.; Gill S. C.; Lim N. M.; Mobley D. L. Sampling Conformational Changes of Bound Ligands Using Nonequilibrium Candidate Monte Carlo and Molecular Dynamics. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2020, 16 (3), 1854–1865. 10.1021/acs.jctc.9b01066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Degiacomi M. T. Coupling Molecular Dynamics and Deep Learning to Mine Protein Conformational Space. Structure 2019, 27 (6), 1034–1040.e3. 10.1016/j.str.2019.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Noé F.; De Fabritiis G.; Clementi C. Machine Learning for Protein Folding and Dynamics. Current Opinion in Structural Biology 2020, 60, 77–84. 10.1016/j.sbi.2019.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Yuan J.-H.; Han S. B.; Richter S.; Wade R. C.; Kokh D. B. Druggability Assessment in TRAPP Using Machine Learning Approaches. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2020, 60 (3), 1685–1699. 10.1021/acs.jcim.9b01185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Jumper J.; Evans R.; Pritzel A.; Green T.; Figurnov M.; Ronneberger O.; Tunyasuvunakool K.; Bates R.; Žídek A.; Potapenko A.; Bridgland A.; Meyer C.; Kohl S. A. A.; Ballard A. J.; Cowie A.; Romera-Paredes B.; Nikolov S.; Jain R.; Adler J.; Back T.; Petersen S.; Reiman D.; Clancy E.; Zielinski M.; Steinegger M.; Pacholska M.; Berghammer T.; Bodenstein S.; Silver D.; Vinyals O.; Senior A. W.; Kavukcuoglu K.; Kohli P.; Hassabis D. Highly Accurate Protein Structure Prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596 (7873), 583–589. 10.1038/s41586-021-03819-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Motta S.; Callea L.; Bonati L.; Pandini A. PathDetect-SOM: A Neural Network Approach for the Identification of Pathways in Ligand Binding Simulations. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2022, 18 (3), 1957–1968. 10.1021/acs.jctc.1c01163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Zhang Y.; Li S.; Meng K.; Sun S. Machine Learning for Sequence and Structure-Based Protein–Ligand Interaction Prediction. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2024, 64 (5), 1456–1472. 10.1021/acs.jcim.3c01841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Müllender L.; Rizzi A.; Parrinello M.; Carloni P.; Mandelli D. Effective Data-Driven Collective Variables for Free Energy Calculations from Metadynamics of Paths. PNAS Nexus 2024, 3 (4), pgae159. 10.1093/pnasnexus/pgae159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Amaro R. E.; Baudry J.; Chodera J.; Demir Ö.; McCammon J. A.; Miao Y.; Smith J. C. Ensemble Docking in Drug Discovery. Biophysical Journal 2018, 114 (10), 2271–2278. 10.1016/j.bpj.2018.02.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Buonfiglio R.; Recanatini M.; Masetti M. Protein Flexibility in Drug Discovery: From Theory to Computation. ChemMedChem 2015, 10 (7), 1141–1148. 10.1002/cmdc.201500086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Antunes D. A.; Devaurs D.; Kavraki L. E. Understanding the Challenges of Protein Flexibility in Drug Design. Expert Opinion on Drug Discovery 2015, 10 (12), 1301–1313. 10.1517/17460441.2015.1094458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Caballero J. The Latest Automated Docking Technologies for Novel Drug Discovery. Expert Opinion on Drug Discovery 2020, 1–21. 10.1080/17460441.2021.1858793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Harmalkar A.; Gray J. J. Advances to Tackle Backbone Flexibility in Protein Docking. Current Opinion in Structural Biology 2021, 67, 178–186. 10.1016/j.sbi.2020.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Saldaño T.; Escobedo N.; Marchetti J.; Zea D. J.; Mac Donagh J.; Velez Rueda A. J.; Gonik E.; García Melani A.; Novomisky Nechcoff J.; Salas M. N.; Peters T.; Demitroff N.; Fernandez Alberti S.; Palopoli N.; Fornasari M. S.; Parisi G. Impact of Protein Conformational Diversity on AlphaFold Predictions. Bioinformatics 2022, 38 (10), 2742–2748. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btac202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Qiao Z.; Nie W.; Vahdat A.; Miller T. F.; Anandkumar A. State-Specific Protein–Ligand Complex Structure Prediction with a Multiscale Deep Generative Model. Nat Mach Intell 2024, 6 (2), 195–208. 10.1038/s42256-024-00792-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Huang S.-Y.; Zou X. Ensemble Docking of Multiple Protein Structures: Considering Protein Structural Variations in Molecular Docking. Proteins 2006, 66 (2), 399–421. 10.1002/prot.21214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Kapoor K.; Thangapandian S.; Tajkhorshid E. Extended-Ensemble Docking to Probe Dynamic Variation of Ligand Binding Sites during Large-Scale Structural Changes of Proteins. Chem. Sci. 2022, 13 (14), 4150–4169. 10.1039/D2SC00841F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Acharya A.; Agarwal R.; Baker M. B.; Baudry J.; Bhowmik D.; Boehm S.; Byler K. G.; Chen S. Y.; Coates L.; Cooper C. J.; Demerdash O.; Daidone I.; Eblen J. D.; Ellingson S.; Forli S.; Glaser J.; Gumbart J. C.; Gunnels J.; Hernandez O.; Irle S.; Kneller D. W.; Kovalevsky A.; Larkin J.; Lawrence T. J.; LeGrand S.; Liu S.-H.; Mitchell J. C.; Park G.; Parks J. M.; Pavlova A.; Petridis L.; Poole D.; Pouchard L.; Ramanathan A.; Rogers D. M.; Santos-Martins D.; Scheinberg A.; Sedova A.; Shen Y.; Smith J. C.; Smith M. D.; Soto C.; Tsaris A.; Thavappiragasam M.; Tillack A. F.; Vermaas J. V.; Vuong V. Q.; Yin J.; Yoo S.; Zahran M.; Zanetti-Polzi L. Supercomputer-Based Ensemble Docking Drug Discovery Pipeline with Application to Covid-19. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2020, 60 (12), 5832–5852. 10.1021/acs.jcim.0c01010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Meller A.; Lotthammer J. M.; Smith L. G.; Novak B.; Lee L. A.; Kuhn C. C.; Greenberg L.; Leinwand L. A.; Greenberg M. J.; Bowman G. R. Drug Specificity and Affinity Are Encoded in the Probability of Cryptic Pocket Opening in Myosin Motor Domains. eLife 2023, 12, e83602. 10.7554/eLife.83602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Akbari Z.; Stagno C.; Iraci N.; Efferth T.; Omer E. A.; Piperno A.; Montazerozohori M.; Feizi-Dehnayebi M.; Micale N. Biological Evaluation, DFT, MEP, HOMO-LUMO Analysis and Ensemble Docking Studies of Zn(II) Complexes of Bidentate and Tetradentate Schiff Base Ligands as Antileukemia Agents. Journal of Molecular Structure 2024, 1301, 137400. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2023.137400. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Ricci-Lopez J.; Aguila S. A.; Gilson M. K.; Brizuela C. A. Improving Structure-Based Virtual Screening with Ensemble Docking and Machine Learning. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2021, 61 (11), 5362–5376. 10.1021/acs.jcim.1c00511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Basciu A.; Malloci G.; Pietrucci F.; Bonvin A. M. J. J.; Vargiu A. V. Holo-like and Druggable Protein Conformations from Enhanced Sampling of Binding Pocket Volume and Shape. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2019, 59 (4), 1515–1528. 10.1021/acs.jcim.8b00730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Basciu A.; Koukos P. I.; Malloci G.; Bonvin A. M. J. J.; Vargiu A. V. Coupling Enhanced Sampling of the Apo-Receptor with Template-Based Ligand Conformers Selection: Performance in Pose Prediction in the D3R Grand Challenge 4. J Comput Aided Mol Des 2020, 34 (2), 149–162. 10.1007/s10822-019-00244-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Basciu A.; Callea L.; Motta S.; Bonvin A. M. J. J.; Bonati L.; Vargiu A. V. No Dance, No Partner! A Tale of Receptor Flexibility in Docking and Virtual Screening. In Annual Reports in Medicinal Chemistry; Elsevier, 2022; Vol. 59, pp 43–97. 10.1016/bs.armc.2022.08.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Laio A.; Parrinello M. Escaping Free-Energy Minima. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2002, 99 (20), 12562–12566. 10.1073/pnas.202427399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Barducci A.; Bussi G.; Parrinello M. Well-Tempered Metadynamics: A Smoothly Converging and Tunable Free-Energy Method. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 100 (2), 020603. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.020603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Piana S.; Laio A. A Bias-Exchange Approach to Protein Folding. J. Phys. Chem. B 2007, 111 (17), 4553–4559. 10.1021/jp067873l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Zuo K.; Kranjc A.; Capelli R.; Rossetti G.; Nechushtai R.; Carloni P. Metadynamics Simulations of Ligands Binding to Protein Surfaces: A Novel Tool for Rational Drug Design. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2023, 25 (20), 13819–13824. 10.1039/D3CP01388J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Cavalli A.; Spitaleri A.; Saladino G.; Gervasio F. L. Investigating Drug–Target Association and Dissociation Mechanisms Using Metadynamics-Based Algorithms. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48 (2), 277–285. 10.1021/ar500356n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Nussinov R.; Tsai C.-J. Allostery in Disease and in Drug Discovery. Cell 2013, 153 (2), 293–305. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Sheik Amamuddy O.; Veldman W.; Manyumwa C.; Khairallah A.; Agajanian S.; Oluyemi O.; Verkhivker G. M.; Tastan Bishop Ö. Integrated Computational Approaches and Tools for Allosteric Drug Discovery. IJMS 2020, 21 (3), 847. 10.3390/ijms21030847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Ionescu M. I. Adenylate Kinase: A Ubiquitous Enzyme Correlated with Medical Conditions. Protein J 2019, 38 (2), 120–133. 10.1007/s10930-019-09811-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Carling D. AMPK Signalling in Health and Disease. Current Opinion in Cell Biology 2017, 45, 31–37. 10.1016/j.ceb.2017.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Müller C.; Schlauderer G.; Reinstein J.; Schulz G. Adenylate Kinase Motions during Catalysis: An Energetic Counterweight Balancing Substrate Binding. Structure 1996, 4 (2), 147–156. 10.1016/S0969-2126(96)00018-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Bae E.; Phillips G. N. Roles of Static and Dynamic Domains in Stability and Catalysis of Adenylate Kinase. PNAS 2006, 103 (7), 2132–2137. 10.1073/pnas.0507527103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Liu R.; Xu H.; Wei Z.; Wang Y.; Lin Y.; Gong W. Crystal Structure of Human Adenylate Kinase 4 (L171P) Suggests the Role of Hinge Region in Protein Domain Motion. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2009, 379 (1), 92–97. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Berry M. B.; Meador B.; Bilderback T.; Liang P.; Glaser M.; Phillips G. N. The Closed Conformation of a Highly Flexible Protein: The Structure ofE. Coli Adenylate Kinase with Bound AMP and AMPPNP. Proteins 1994, 19 (3), 183–198. 10.1002/prot.340190304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Schulz G. E.; Müller C. W.; Diederichs K. Induced-Fit Movements in Adenylate Kinases. Journal of Molecular Biology 1990, 213 (4), 627–630. 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80250-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Wu P.; Nielsen T. E.; Clausen M. H. FDA-Approved Small-Molecule Kinase Inhibitors. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences 2015, 36 (7), 422–439. 10.1016/j.tips.2015.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Arrowsmith C. H.; Bountra C.; Fish P. V.; Lee K.; Schapira M. Epigenetic Protein Families: A New Frontier for Drug Discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2012, 11 (5), 384–400. 10.1038/nrd3674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Whitford P. C.; Gosavi S.; Onuchic J. N. Conformational Transitions in Adenylate Kinase: ALLOSTERIC COMMUNICATION REDUCES MISLIGATION. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283 (4), 2042–2048. 10.1074/jbc.M707632200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Potoyan D. A.; Zhuravlev P. I.; Papoian G. A. Computing Free Energy of a Large-Scale Allosteric Transition in Adenylate Kinase Using All Atom Explicit Solvent Simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B 2012, 116 (5), 1709–1715. 10.1021/jp209980b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Daily M. D.; Phillips G. N.; Cui Q. Many Local Motions Cooperate to Produce the Adenylate Kinase Conformational Transition. Journal of Molecular Biology 2010, 400 (3), 618–631. 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Kerns S. J.; Agafonov R. V.; Cho Y.-J.; Pontiggia F.; Otten R.; Pachov D. V.; Kutter S.; Phung L. A.; Murphy P. N.; Thai V.; Alber T.; Hagan M. F.; Kern D. The Energy Landscape of Adenylate Kinase during Catalysis. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2015, 22 (2), 124–131. 10.1038/nsmb.2941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Lassila J. K.; Zalatan J. G.; Herschlag D. Biological Phosphoryl-Transfer Reactions: Understanding Mechanism and Catalysis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2011, 80 (1), 669–702. 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060409-092741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Rogne P.; Rosselin M.; Grundström C.; Hedberg C.; Sauer U. H.; Wolf-Watz M. Molecular Mechanism of ATP versus GTP Selectivity of Adenylate Kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2018, 115 (12), 3012–3017. 10.1073/pnas.1721508115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Vonrhein C.; Schlauderer G. J.; Schulz G. E. Movie of the Structural Changes during a Catalytic Cycle of Nucleoside Monophosphate Kinases. Structure 1995, 3 (5), 483–490. 10.1016/S0969-2126(01)00181-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Kovermann M.; Grundström C.; Sauer-Eriksson A. E.; Sauer U. H.; Wolf-Watz M. Structural Basis for Ligand Binding to an Enzyme by a Conformational Selection Pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2017, 114 (24), 6298–6303. 10.1073/pnas.1700919114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Hanson J. A.; Duderstadt K.; Watkins L. P.; Bhattacharyya S.; Brokaw J.; Chu J.-W.; Yang H. Illuminating the Mechanistic Roles of Enzyme Conformational Dynamics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2007, 104 (46), 18055–18060. 10.1073/pnas.0708600104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).Scheerer D.; Adkar B. V.; Bhattacharyya S.; Levy D.; Iljina M.; Riven I.; Dym O.; Haran G.; Shakhnovich E. I. Allosteric Communication between Ligand Binding Domains Modulates Substrate Inhibition in Adenylate Kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2023, 120 (18), e2219855120. 10.1073/pnas.2219855120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (69).Ionescu M.; Oniga O. Molecular Docking Evaluation of (E)-5-Arylidene-2-Thioxothiazolidin-4-One Derivatives as Selective Bacterial Adenylate Kinase Inhibitors. Molecules 2018, 23 (5), 1076. 10.3390/molecules23051076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (70).Li D.; Liu M. S.; Ji B. Mapping the Dynamics Landscape of Conformational Transitions in Enzyme: The Adenylate Kinase Case. Biophysical Journal 2015, 109 (3), 647–660. 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.06.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (71).Kruger D. M.; Ahmed A.; Gohlke H. NMSim Web Server: Integrated Approach for Normal Mode-Based Geometric Simulations of Biologically Relevant Conformational Transitions in Proteins. Nucleic Acids Research 2012, 40 (W1), W310–W316. 10.1093/nar/gks478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (72).Ahmed A.; Rippmann F.; Barnickel G.; Gohlke H. A Normal Mode-Based Geometric Simulation Approach for Exploring Biologically Relevant Conformational Transitions in Proteins. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling 2011, 51 (7), 1604–1622. 10.1021/ci100461k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (73).Lu Q.; Wang J. Single Molecule Conformational Dynamics of Adenylate Kinase: Energy Landscape, Structural Correlations, and Transition State Ensembles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130 (14), 4772–4783. 10.1021/ja0780481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (74).Seyler S. L.; Beckstein O. Sampling Large Conformational Transitions: Adenylate Kinase as a Testing Ground. Molecular Simulation 2014, 40 (10–11), 855–877. 10.1080/08927022.2014.919497. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (75).Formoso E.; Limongelli V.; Parrinello M. Energetics and Structural Characterization of the Large-Scale Functional Motion of Adenylate Kinase. Sci Rep 2015, 5 (1), 8425. 10.1038/srep08425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (76).Yasuda T.; Shigeta Y.; Harada R. Efficient Conformational Sampling of Collective Motions of Proteins with Principal Component Analysis-Based Parallel Cascade Selection Molecular Dynamics. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2020, 60 (8), 4021–4029. 10.1021/acs.jcim.0c00580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (77).Jalalypour F.; Sensoy O.; Atilgan C. Perturb–Scan–Pull: A Novel Method Facilitating Conformational Transitions in Proteins. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2020, 16 (6), 3825–3841. 10.1021/acs.jctc.9b01222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (78).Wang J.; Peng C.; Yu Y.; Chen Z.; Xu Z.; Cai T.; Shao Q.; Shi J.; Zhu W. Exploring Conformational Change of Adenylate Kinase by Replica Exchange Molecular Dynamic Simulation. Biophysical Journal 2020, 118 (5), 1009–1018. 10.1016/j.bpj.2020.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (79).Uyar A.; Kantarci-Carsibasi N.; Haliloglu T.; Doruker P. Features of Large Hinge-Bending Conformational Transitions. Prediction of Closed Structure from Open State. Biophysical Journal 2014, 106 (12), 2656–2666. 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (80).Zeller F.; Zacharias M. Substrate Binding Specifically Modulates Domain Arrangements in Adenylate Kinase. Biophysical Journal 2015, 109 (9), 1978–1985. 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.08.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (81).Kurkcuoglu Z.; Doruker P. Ligand Docking to Intermediate and Close-To-Bound Conformers Generated by an Elastic Network Model Based Algorithm for Highly Flexible Proteins. PLoS ONE 2016, 11 (6), e0158063. 10.1371/journal.pone.0158063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (82).Lou H.; Cukier R. I. Molecular Dynamics of Apo-Adenylate Kinase: A Principal Component Analysis. J. Phys. Chem. B 2006, 110 (25), 12796–12808. 10.1021/jp061976m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (83).Nam K.; Arattu Thodika A. R.; Grundström C.; Sauer U. H.; Wolf-Watz M. Elucidating Dynamics of Adenylate Kinase from Enzyme Opening to Ligand Release. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2024, 64 (1), 150–163. 10.1021/acs.jcim.3c01618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (84).Fiorentini R.; Tarenzi T.; Potestio R. Fast, Accurate, and System-Specific Variable-Resolution Modeling of Proteins. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2023, 63 (4), 1260–1275. 10.1021/acs.jcim.2c01311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (85).Kanada R.; Terayama K.; Tokuhisa A.; Matsumoto S.; Okuno Y. Enhanced Conformational Sampling with an Adaptive Coarse-Grained Elastic Network Model Using Short-Time All-Atom Molecular Dynamics. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2022, 18 (4), 2062–2074. 10.1021/acs.jctc.1c01074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (86).Yuan Y.; Zhu Q.; Song R.; Ma J.; Dong H. A Two-Ended Data-Driven Accelerated Sampling Method for Exploring the Transition Pathways between Two Known States of Protein. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2020, 16 (7), 4631–4640. 10.1021/acs.jctc.9b01184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (87).Yang S.; Song C. Switching Go -Martini for Investigating Protein Conformational Transitions and Associated Protein–Lipid Interactions. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2024, 20 (6), 2618–2629. 10.1021/acs.jctc.3c01222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (88).Wang Y.; Makowski L. Fine Structure of Conformational Ensembles in Adenylate Kinase. Proteins 2018, 86 (3), 332–343. 10.1002/prot.25443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (89).Henzler-Wildman K. A.; Thai V.; Lei M.; Ott M.; Wolf-Watz M.; Fenn T.; Pozharski E.; Wilson M. A.; Petsko G. A.; Karplus M.; Hübner C. G.; Kern D. Intrinsic Motions along an Enzymatic Reaction Trajectory. Nature 2007, 450 (7171), 838–844. 10.1038/nature06410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (90).Shao Q. Enhanced Conformational Sampling Technique Provides an Energy Landscape View of Large-Scale Protein Conformational Transitions. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18 (42), 29170–29182. 10.1039/C6CP05634B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (91).Punia R.; Goel G. Computation of the Protein Conformational Transition Pathway on Ligand Binding by Linear Response-Driven Molecular Dynamics. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2022, 18 (5), 3268–3283. 10.1021/acs.jctc.1c01243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (92).Wu Q.; Peng Z.; Zhang Y.; Yang J. COACH-D: Improved Protein–Ligand Binding Sites Prediction with Refined Ligand-Binding Poses through Molecular Docking. Nucleic Acids Research 2018, 46 (W1), W438–W442. 10.1093/nar/gky439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (93).Müller C.; Schlauderer G.; Reinstein J.; Schulz G. Adenylate Kinase Motions during Catalysis: An Energetic Counterweight Balancing Substrate Binding. Structure 1996, 4 (2), 147–156. 10.1016/S0969-2126(96)00018-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (94).Müller C. W.; Schulz G. E. Structure of the Complex between Adenylate Kinase from Escherichia Coli and the Inhibitor Ap5A Refined at 1.9 Å Resolution. Journal of Molecular Biology 1992, 224 (1), 159–177. 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90582-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (95).Berry M. B.; Bae E.; Bilderback T. R.; Glaser M.; Phillips G. N. Crystal Structure of ADP/AMP Complex of Escherichia Coli Adenylate Kinase. Proteins 2005, 62 (2), 555–556. 10.1002/prot.20699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]