Abstract

Intra-genomic conflict driven by selfish chromosomes is a powerful force that shapes the evolution of genomes and species. In the male germline, many selfish chromosomes bias transmission in their own favor by eliminating spermatids bearing the competing homologous chromosomes. However, the mechanisms of targeted gamete elimination remain mysterious. Here, we show that Overdrive (Ovd), a gene required for both segregation distortion and male sterility in Drosophila pseudoobscura hybrids, is broadly conserved in Dipteran insects but dispensable for viability and fertility. In D. melanogaster, Ovd is required for targeted Responder spermatid elimination after the histone-to-protamine transition in the classical Segregation Distorter system. We propose that Ovd functions as a general spermatid quality checkpoint that is hijacked by independent selfish chromosomes to eliminate competing gametes.

Mendelian segregation is the foundation on which our understanding of genetics and population genetic theory rests. Segregation distorters are selfish chromosomes that violate Mendel’s Laws by over-representing themselves in the mature gamete pool of individuals that carry them (1, 2). In the male germline, distorters act by selectively eliminating spermatozoa that carry their competing homologous chromosomes (3). Although a few segregation distorter genes have been identified, the mechanisms underlying the selective elimination of competing gametes remain poorly understood (4–7).

In Drosophila, some selfish chromosomes act by directly disrupting target chromosome segregation during meiosis (5). In other distorter systems, drive mechanisms involve the elimination of post-meiotic spermatids (8–10). During Drosophila spermiogenesis, groups of interconnected spermatids elongate and condense their nuclei into highly compact, needle-shaped sperm heads (11, 12). This is achieved through a global chromatin remodeling process where almost all histones are progressively replaced first by transition proteins, such as Tpl94D, which are in turn replaced by Sperm Nuclear Basic Proteins (SNBPs), such as the Protamine-like ProtA and ProtB (13, 14). One of the best-described distorter systems is Segregation Distorter (SD) in Drosophila melanogaster (8, 15). In this system, selfish SD chromosomes selectively disrupt the histone-to-protamine transition in spermatid nuclei that carry an SD-sensitive homolog known as Responder (Rsp) (16–18). In SD/Rsp males, Rsp spermatid nuclei fail to condense properly and are eliminated during spermatid individualization. This is a common stage of spermiogenic failure observed in a variety of perturbations including male sterile mutants, high temperature induced sterility, etc. (19, 20). This has led to speculation that a general male germline checkpoint may exist during spermatid individualization (16, 21, 22). However, the mechanisms of elimination of Rsp sperm remain unknown.

Intra-genomic conflict involving segregation distorters provides a leading explanation for the rapid evolution of hybrid male sterility but evidence for this idea remains scarce (23–27). A direct line of evidence connecting intra-genomic conflict to speciation comes from hybrids between two very young subspecies: Drosophila pseudoobscura bogotana (Bogota) and Drosophila pseudoobscura pseudoobscura (USA) (28). F1 hybrid males from crosses between Bogota mothers and USA fathers are nearly sterile but become weakly fertile when aged (29). These aged hybrid males produce nearly all female progeny due to segregation distortion by the Bogota X-chromosome. Although the genetic basis of segregation distortion and male sterility in these hybrids involves a complex genetic architecture, a single gene Overdrive (Ovd) is involved in both phenomena (7, 30). Yet, little is known about the normal function of Ovd within species or its mechanistic role in segregation distortion and male sterility between species.

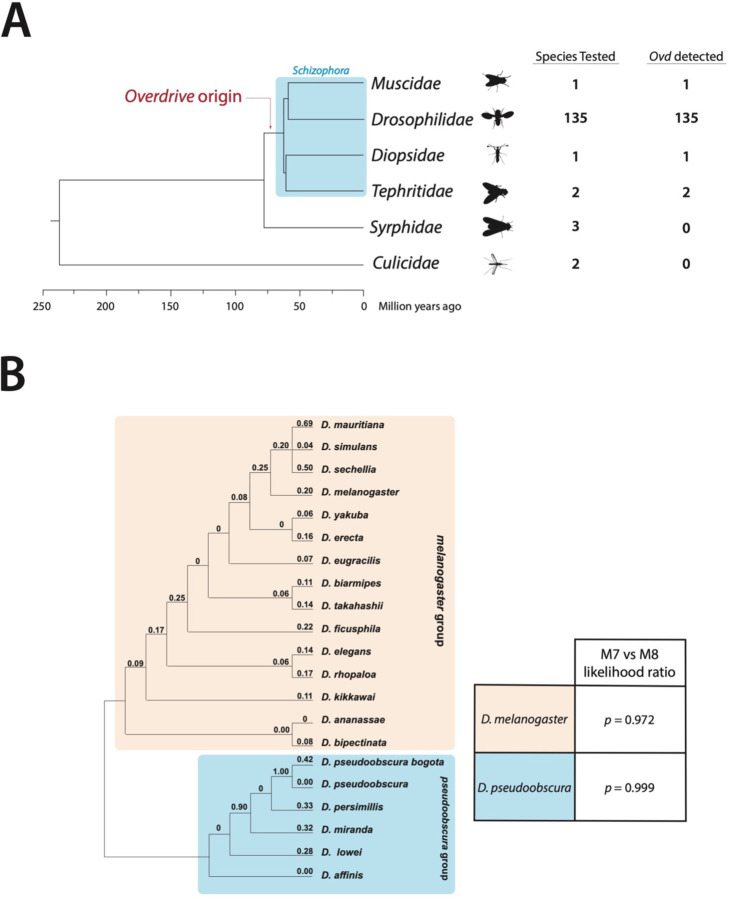

First, we wanted to understand the origins and patterns of molecular evolution of Ovd. To date the origins of Ovd, we used reciprocal BLAST and synteny analyses to search for orthologs of Ovd across Diptera. Ovd is present in all Drosophilidae and Schizophora species analyzed, but not detected outside of Schizophora (Figure 1A). Based on time-calibrated phylogenies of Dipterans and Schizophora (31, 32), we conclude that Ovd originated at least 60 million years ago in the ancestor of Schizophora and has since been maintained without loss. Hybrid sterility and segregation distortion genes tend to change rapidly under recurrent positive selection (5, 7, 33, 34). We used PAML (Phylogenetic Analysis by Maximum Likelihood) (35) to search for signatures of recurrent positive selection in Ovd in the melanogaster and obscura clades. Surprisingly, we did not observe high dN/ds values for Ovd, nor did any individual lineage show accelerated accumulation of nonsynonymous substitutions (Figure 1B). Models of molecular evolution allowing for positive selection were not a significantly better fit than those that excluded it (p = 0.972 for melanogaster group species and p = 0.999 for obscura group species, likelihood ratio test). No individual residues within Ovd showed signatures of positive selection. Despite being involved in both segregation distortion and hybrid sterility, Ovd is surprisingly conserved and shows no signs of accelerated evolution.

Figure 1: Overdrive has been maintained without loss since its origin at least 65 million years ago and does not evolve rapidly under positive selection.

(A) We searched for orthologs of Ovd in 139 species of Dipterans using reciprocal BLAST and synteny checks. Orthologs of Ovd were detected in all Schizophora species tested but not detected outside of Schizophora. Time-calibrated phylogenies of Schizophora and Dipterans allow time estimates for our phylogeny (31, 32). (B) Cladogram of Ovd sequence evolution across melanogaster (orange) and pseudoobscura (blue) groups with dN/dS values for each branch calculated with the PAML package. Ovd does not evolve under recurrent positive selection as denoted by p-values from M7 vs M8 model comparisons.

Because Ovd is a conserved gene and can cause sterility and segregation distortion in Bogota-USA hybrids, we wondered if it is essential for male germline development. We used CRISPR/Cas9-based gene editing to generate null mutants of Ovd in both the USA and Bogota subspecies (Figure 2A). Surprisingly, Ovd-null individuals from either subspecies were fertile. We observed no difference in male fertility, sex-chromosome segregation ratios, or viability between OvdΔ and wild-type controls in either subspecies (Figure 2B, 2C, 2D). Ovd thus appears to be dispensable for viability and male germline development in D. pseudoobscura.

Figure 2: Ovd is non-essential in D. pseudoobscura in pure species but removing it restores fertility and normal segregation in interspecies F1 hybrid males.

(A) Schematic showing CRISPR-Cas9 NHEJ knockouts of Ovd where nearly the whole coding region is deleted in USA and Bogota subspecies of D. pseudoobscura. (B) Viability of OvdΔ and wild-type crosses in both D. pseudoobscura subspecies. Viability of OvdΔ and wild-type individuals are not significantly different (p=0.10 for USA; p=0.056 for Bogota; two sample Student’s t-test) (C) Male fertility of OvdΔ and wild-type individuals are not significantly different (p=0.73 for USA; p=0.54 for Bogota; two sample Student’s t-test). (D) Sex-ratio of progeny produced by OvdΔ and wild-type males in both D. pseudoobscura subspecies. Progeny sex-ratios between OvdΔ and wild-type individuals are not statistically significant (p=0.87 for USA; p=0.33 for Bogota; two sample Student’s t-test). (E) Crossing schematic and fertility of F1 hybrid males produced by crossing either OvdΔ or Ovd+ Bogota females to USA males. Deleting Ovd restores fertility to otherwise sterile F1 hybrid males (p=0.002; Wilcoxon test).

Previously, we showed that replacing an incompatible Bogota allele of Ovd with a compatible USA allele restores fertility and normal segregation to F1 hybrid males (7). However, it is not clear whether F1 hybrid males are sterile because they lack a USA allele of Ovd that provides an essential function or because the presence of the Bogota allele blocks male germline development. To discriminate between these possibilities, we crossed Bogota females with or without Ovd to USA males to produce F1 hybrid males (Figure 2E). In the control Ovd+ cross, all F1 hybrid males were sterile, as expected. In contrast, OvdΔ hybrid F1 males were fertile and showed normal sex-chromosome segregation ratios. We conclude that Ovd is not required for normal male germline development in pure species, but the presence of Bogota Ovd can block male germline development in hybrids.

Although Ovd is not an essential gene, its conservation across long evolutionary timescales suggests that it may have an important function. We hypothesized that Ovd may be involved in a putative male germline checkpoint. An Ovd-mediated checkpoint could explain three distinct observations. First, Ovd is dispensable for normal germline development because removing such a checkpoint would have no discernable effect in the absence of perturbation. For example, null mutants of known DNA damage checkpoint genes, such as p53 and Chk-2 kinase, are viable and develop normally, but only show an effect in the presence of DNA damage (36, 37). Second, removing Ovd restores normal segregation in hybrids. If an Ovd-mediated checkpoint specifically arrests only spermatids targeted for elimination, this would cause segregation distortion. Third, removing Ovd restores hybrid male fertility. If an Ovd-mediated checkpoint arrests all spermatids, this would cause sterility (Figure 3A).

Figure 3: Overdrive is non-essential for viability and fertility in D. melanogaster.

(A) A model for a role for Ovd in a germline checkpoint can explain why Ovd is dispensable for male germline development but is required for segregation distortion and male sterility. (B) Schematic for the design of D. melanogaster Ovd knockout. We use CRISPR-Cas9 to replace the coding sequence of Ovd with DsRed, a visible marker. (C) Progeny counts for OvdΔ crosses show that it is not essential for viability. OvdΔ shows no viability deficit relative to TM3 balancer. The number of progeny of OvdΔ /TM3 heterozygote pairs did not deviate significantly from the expected Mendelian ratio of 2:1 OvdΔ/TM3:OvdΔ/OvdΔ (p = 0.08, Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test). (D) Male fertility for OvdΔ. The number of progeny produced per male for wildtype Ovd, heterozygous for OvdΔ, and homozygous for OvdΔ are not significantly different from each other (one-way ANOVA; p = 0.124) (E) Sex-ratio of progeny produced by males wildtype for Ovd, heterozygous for OvdΔ, and homozygous for OvdΔ are not significantly differently from each other (one-way ANOVA; p = 0.875). (F) Nondisjunction rates for sex chromosomes and the fourth chromosome in w1118 and OvdΔ males. Sex chromosome nondisjunction frequencies do not differ significantly between the genotypes, nor do fourth chromosome nondisjunction frequencies. (G) k-values for SD/Rspss males with wild-type Ovd, heterozygous OvdΔ and homozygous OvdΔ for SD-72 and SD-5 chromosomes. Homozygous OvdΔ males show reduced strength of distortion (p < 0.05, Three-way ANOVA, Tukey’s Honestly Significant Differences test). (H) Progeny count per male for SD/Rspss males with wild-type Ovd, heterozygous OvdΔ and homozygous OvdΔ. Homozygous OvdΔ males produce more progeny than wild-type Ovd and heterozygous OvdΔ males in an SD background (p < 0.05, Three-way ANOVA, Tukey’s Honestly Significant Differences test)

To test its hypothetical male germline checkpoint function, we switched to studying Ovd in Drosophila melanogaster, where more genetic and cytological tools are available. The predicted Ovd protein has a MADF DNA-binding domain and a BESS protein-interaction domain. MADF-BESS domain-containing proteins are involved in diverse processes such as transcriptional regulation and chromatin remodeling (38–40). We first studied the expression and localization pattern of Ovd in testes by introducing an N-terminus GFP-tag at the endogenous locus using CRISPR/Cas9. Testis imaging shows that Ovd is a nuclear protein expressed during spermatogenesis from male germline stem cells through the histone-to-protamine transition stages (Supplemental figure S1). Next, we used CRISPR/Cas9 to delete Ovd in D. melanogaster (Figure 3B, Supplemental figure S2). We observed little difference between male fertility, progeny sex-ratio, viability, or chromosomal non-disjunction rates between OvdΔ and wild type controls (Figure 3C, 3D, 3E, 3F). Like in D. pseudoobscura, Ovd is not essential for normal male germline development in D. melanogaster.

If Ovd functions in a male germline checkpoint, then sperm that are normally eliminated in response to perturbations may develop to maturity when Ovd is removed. We turned to the Segregation Distorter (SD) system to perturb male germline development in D. melanogaster. We hypothesized that when Ovd is removed, SD chromosomes would fail to eliminate gametes bearing homologous chromosomes with Rsp satellite repeats. We first measured the strength of distortion by the SD-72 chromosome against Rspss, a supersensitive Rsp chromosome, and observed near-complete distortion as expected (k > 0.99). We then measured the strength of distortion by the same SD-72 chromosome against Rspss in an OvdΔ homozygous background. We observed a strong reduction in the strength of distortion by SD-72 in the absence of Ovd (k~0.65; Figure 3G). We repeated our measurements with an independently isolated SD chromosome, SD-5 (8). Again, we found a strong reduction in the strength of distortion by SD-5 in an Ovd homozygous null background (Figure 3H). SD thus requires Ovd for full-strength distortion. Together, our results show that Ovd is required for both sex-chromosome distortion in D. pseudoobscura, and autosomal distortion in D. melanogaster.

We then investigated spermiogenesis in SD males in the presence or absence of Ovd. In SD-72/Rspss males, spermiogenesis appears highly disturbed with many abnormal spermatid nuclei being eliminated, a typical phenotype of SD males (16). In contrast, spermiogenesis in SD-72/Rspss males appeared overall normal in an OvdΔ homozygous background (Figure 4A). We then examined the histone-to-protamine transition in these males using Tpl94D-RFP and ProtB-GFP transgenes. As previously observed (16), about half spermatid nuclei showed a delay in protamine incorporation and elongation defects in SD males (Figure 4B). These nuclei fail to individualize and are eliminated before their release into the seminal vesicle, the sperm storage organ in males. In contrast, in an OvdΔ homozygous background, nearly all spermatids incorporate protamine and elongate properly (Figure 4A). Removing Ovd thus appears to restore proper histone-to-protamine transition and individualization to Rsp sperm even in the presence of SD. To assess the quality of sperm nuclei produced by SD males that lack Ovd, we stained seminal vesicles with an antibody that recognizes double stranded DNA (dsDNA). We have previously shown that this antibody can stain improperly compacted chromatin in mature Rsp sperm nuclei but not properly condensed sperm nuclei which are refractory to immuno-staining (16). Remarkably, we observed a significant increase of anti-dsDNA positive sperm in seminal vesicles of SD/Rspss males lacking Ovd compared to SD/Rspss males with Ovd (30% decondensed vs. 4% decondensed) (Figure 4C, 4D). We conclude that, when Ovd is removed, Rsp spermatids differentiate to maturity despite chromatin condensation defects caused by SD. Because these sperm produce viable Rspss progeny, these condensation defects are not fatal. Taken together, these results indicate that Ovd does not itself cause condensation defects in mature sperm but is instead required for the selective elimination of improperly condensed Rsp spermatids during individualization.

Figure 4: Ovd is required for selective elimination of Rsp sperm in the presence of SD in D. melanogaster.

(A) Cysts of 64 spermatids in testes from SD-72/Rspss males with and without Ovd stained with DAPI. With Ovd, cysts are disorganized, half spermatid nuclei fail to elongate and degenerate (arrows). Without Ovd, spermatid elongation is restored. Bar: 10 μm (B) The histone-to-protamine transition of SD-72/Rspss males with and without Ovd. ProtB-GFP and Tpl94D-RFP transgenes are used to visualize protamines and transition proteins, respectively. With Ovd, half of the developing spermatids fail to incorporate protamines and do not elongate properly (arrows). Without Ovd, all sperm undergo the histone-to-protamine transition and elongation appropriately. Bar: 10 μm (C) Seminal vesicles of SD-72/Rspss males with and without Ovd stained with an anti-dsDNA antibody to reveal improperly condensed sperm nuclei. Bar: 50 μm. (D) Quantification of decondensed sperm in seminal vesicles of SD-72/Rspss males with and without Ovd, with w1118 and OvdΔ/OvdΔ as controls. There is a significant increase in number of anti-dsDNA positive sperm nuclei from SD-72/Rspss; OvdΔ/OvdΔ males compared to SD-72/Rspss; Ovd+/Ovd+ males (Wilcoxon Test; p < 0.01). Each dot corresponds to a male, decondensed sperm from one seminal vesicle was quantified per male.

Ovd is necessary for sex-chromosome segregation distortion and male sterility in D. pseudoobscura hybrids, and for autosomal segregation distortion in D. melanogaster SD males. Although Ovd is dispensable for normal spermiogenesis, it is evolutionarily conserved and blocks proper histone-to-protamine transition in Rsp spermatids in D. melanogaster SD males. Together, these properties suggest that the normal function of Ovd may involve the elimination of abnormal gametes during male germline development, which may get co-opted by selfish chromosomes.

It is worth noting the relationship between the genomic location of Ovd and its rate of evolutionary change. In D. pseudoobscura, Ovd is located on the distorting Bogota X-chromosome and rapidly accumulates non-synonymous changes in the Bogota lineage (7). In D. melanogaster, where Ovd is unlinked to the distorter, it is not rapidly evolving (Ovd is on the third chromosome, SD is on the second chromosome). Ovd thus evolves in a manner consistent with being locked in an evolutionary arms race in D. pseudoobscura but appears to act as an unwitting accomplice to SD in D. melanogaster. Nevertheless, Ovd is essential for two distant non-orthologous segregation distorters raising the possibility that independent selfish chromosomes may operate through shared mechanisms. Together, our findings open the door to understanding how mechanisms of gamete elimination may be involved in the evolution of selfish chromosomes within species and contribute to hybrid sterility between species.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Kent Golic for helpful discussions and feedback in improving this manuscript. We thank Titine Loppin for her continued support. Strains are available upon request. This work was supported by the National Institute of Health grant R01GM141422 to NP and French National Research Agency grant ANR-21-CE13-0037 to BL. We acknowledge the contribution of Lyon SFR Biosciences (UAR3444/CNRS, US8/INSERM, ENS de Lyon, UCBL) imaging facility (PLATIM) and fly food production (Arthrotools).

REFERENCES

- 1.Sandler L., Novitski E., Meiotic Drive as an Evolutionary Force. Am. Nat. 91, 105–110 (1957). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lyttle T. W., Segregation distorters. Annu. Rev. Genet. 25, 511–557 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Courret C., Chang C.-H., Wei K. H.-C., Montchamp-Moreau C., Larracuente A. M., Meiotic drive mechanisms: lessons from Drosophila. Proc. Biol. Sci. 286, 20191430 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Merrill C., Bayraktaroglu L., Kusano A., Ganetzky B., Truncated RanGAP encoded by the Segregation Distorter locus of Drosophila. Science 283, 1742–1745 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Helleu Q., Gérard P. R., Dubruille R., Ogereau D., Prud’homme B., Loppin B., Montchamp-Moreau C., Rapid evolution of a Y-chromosome heterochromatin protein underlies sex chromosome meiotic drive. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113, 4110–4115 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tao Y., Araripe L., Kingan S. B., Ke Y., Xiao H., Hartl D. L., A sex-ratio meiotic drive system in Drosophila simulans. II: an X-linked distorter. PLoS Biol. 5, e293 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Phadnis N., Orr H. A., A single gene causes both male sterility and segregation distortion in Drosophila hybrids. Science 323, 376–379 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Larracuente A. M., Presgraves D. C., The selfish Segregation Distorter gene complex of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 192, 33–53 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Policansky D., Ellison J., “Sex Ratio” in Drosophila pseudoobscura: Spermiogenic Failure. Science 169, 888–889 (1970). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vedanayagam J., Herbette M., Mudgett H., Lin C.-J., Lai C.-M., McDonough-Goldstein C., Dorus S., Loppin B., Meiklejohn C., Dubruille R., Lai E. C., Essential and recurrent roles for hairpin RNAs in silencing de novo sex chromosome conflict in Drosophila simulans. PLoS Biol. 21, e3002136 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tokuyasu K. T., Peacock W. J., Hardy R. W., Dynamics of spermiogenesis in Drosophila melanogaster. I. Individualization process. Z. Zellforsch. Mikrosk. Anat. 124, 479–506 (1972). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fuller M. T., “Spermatogenesis” in The Development of Drosophila Melanogaster, Bate A. A. M. M, Ed. (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, New York, NY, 1993), pp. 71–148. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jayaramaiah Raja S., Renkawitz-Pohl R., Replacement by Drosophila melanogaster protamines and Mst77F of histones during chromatin condensation in late spermatids and role of sesame in the removal of these proteins from the male pronucleus. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 6165–6177 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rathke C., Baarends W. M., Jayaramaiah-Raja S., Bartkuhn M., Renkawitz R., Renkawitz-Pohl R., Transition from a nucleosome-based to a protamine-based chromatin configuration during spermiogenesis in Drosophila. J. Cell Sci. 120, 1689–1700 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sandler L., Hiraizumi Y., Sandler I., Meiotic Drive in Natural Populations of Drosophila Melanogaster. I. the Cytogenetic Basis of Segregation-Distortion. Genetics 44, 233–250 (1959). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herbette M., Wei X., Chang C.-H., Larracuente A. M., Loppin B., Dubruille R., Distinct spermiogenic phenotypes underlie sperm elimination in the Segregation Distorter meiotic drive system. PLoS Genet. 17, e1009662 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu C. I., Lyttle T. W., Wu M. L., Lin G. F., Association between a satellite DNA sequence and the Responder of Segregation Distorter in D. melanogaster. Cell 54, 179–189 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hauschteck-Jungen E., Hartl D. L., Defective Histone Transition during Spermiogenesis in Heterozygous Segregation Distorter Males of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 101, 57–69 (1982). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wakimoto B. T., Lindsley D. L., Herrera C., Toward a comprehensive genetic analysis of male fertility in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 167, 207–216 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ben-David G., Miller E., Steinhauer J., Drosophila spermatid individualization is sensitive to temperature and fatty acid metabolism. Spermatogenesis 5, e1006089 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steinhauer J., Separating from the pack: Molecular mechanisms of Drosophila spermatid individualization. Spermatogenesis 5, e1041345 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McKee B. D., Wilhelm K., Merrill C., Ren X., Male sterility and meiotic drive associated with sex chromosome rearrangements in Drosophila. Role of X-Y pairing. Genetics 149, 143–155 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hurst L. D., Pomiankowski A., Causes of sex ratio bias may account for unisexual sterility in hybrids: a new explanation of Haldane’s rule and related phenomena. Genetics 128, 841–858 (1991). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frank S. A., Divergence of meiotic drive-suppression systems as an explanation for sex-biased hybrid sterility and inviability. Evolution 45, 262–267 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patten M. M., Selfish X chromosomes and speciation. Mol. Ecol. 27, 3772–3782 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coyne J. A. & Orr H. A., Speciation (Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA, 2004). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wen J., Duan H., Bejarano F., Okamura K., Fabian L., Brill J. A., Bortolamiol-Becet D., Martin R., Ruby J. G., Lai E. C., Adaptive regulation of testis gene expression and control of male fertility by the Drosophila hairpin RNA pathway. [Corrected]. Mol. Cell 57, 165–178 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Orr H. A., Irving S., Complex epistasis and the genetic basis of hybrid sterility in the Drosophila pseudoobscura Bogota-USA hybridization. Genetics 158, 1089–1100 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Orr H. A., Irving S., Segregation distortion in hybrids between the Bogota and USA subspecies of Drosophila pseudoobscura. Genetics 169, 671–682 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Phadnis N., Genetic Architecture of Male Sterility and Segregation Distortion in Drosophila pseudoobscura Bogota–USA Hybrids. Genetics 189, 1001–1009 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Junqueira A. C. M., Azeredo-Espin A. M. L., Paulo D. F., Marinho M. A. T., Tomsho L. P., Drautz-Moses D. I., Purbojati R. W., Ratan A., Schuster S. C., Large-scale mitogenomics enables insights into Schizophora (Diptera) radiation and population diversity. Sci. Rep. 6, 1–13 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wiegmann B. M., Trautwein M. D., Winkler I. S., Barr N. B., Kim J.-W., Lambkin C., Bertone M. A., Cassel B. K., Bayless K. M., Heimberg A. M., Wheeler B. M., Peterson K. J., Pape T., Sinclair B. J., Skevington J. H., Blagoderov V., Caravas J., Kutty S. N., Schmidt-Ott U., Kampmeier G. E., Thompson F. C., Grimaldi D. A., Beckenbach A. T., Courtney G. W., Friedrich M., Meier R., Yeates D. K., Episodic radiations in the fly tree of life. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108, 5690–5695 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Orr H. A., Masly J. P., Phadnis N., Speciation in Drosophila: from phenotypes to molecules. J. Hered. 98, 103–110 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oliver P. L., Goodstadt L., Bayes J. J., Birtle Z., Roach K. C., Phadnis N., Beatson S. A., Lunter G., Malik H. S., Ponting C. P., Accelerated evolution of the Prdm9 speciation gene across diverse metazoan taxa. PLoS Genet. 5, e1000753 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang Z., PAML 4: phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24, 1586–1591 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee J. H., Lee E., Park J., Kim E., Kim J., Chung J., In vivo p53 function is indispensable for DNA damage-induced apoptotic signaling in Drosophila. FEBS Lett. 550, 5–10 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu J., Xin S., Du W., Drosophila Chk2 is required for DNA damage-mediated cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. FEBS Lett. 508, 394–398 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cutler G., Perry K. M., Tjian R., Adf-1 is a nonmodular transcription factor that contains a TAF-binding Myb-like motif. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18, 2252–2261 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yi X., de Vries H. I., Siudeja K., Rana A., Lemstra W., Brunsting J. F., Kok R. M., Smulders Y. M., Schaefer M., Dijk F., Shang Y., Eggen B. J. L., Kampinga H. H., Sibon O. C. M., Stwl modifies chromatin compaction and is required to maintain DNA integrity in the presence of perturbed DNA replication. Mol. Biol. Cell 20, 983–994 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zinshteyn D., Barbash D. A., Stonewall prevents expression of ectopic genes in the ovary and accumulates at insulator elements in D. melanogaster. PLoS Genet. 18, e1010110 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kurzhals R. L., Titen S. W. A., Xie H. B., Golic K. G., Chk2 and p53 are haploinsufficient with dependent and independent functions to eliminate cells after telomere loss. PLoS genetics 7, e1002103 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gratz S. J., Ukken F. P., Rubinstein C. D., Thiede G., Donohue L. K., Cummings A. M., O’Connor-Giles K. M., Highly specific and efficient CRISPR/Cas9-catalyzed homology-directed repair in Drosophila. Genetics 196, 961–971 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dunckley T., Tucker M., Parker R., The teflon gene is required for maintenance of autosomal homolog pairing at meiosis I in male Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 157, 273–281 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schindelin J., Arganda-Carreras I., Frise E., Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nature Methods 9, 676–682 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Edgar R. C., MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Research 32, 1792–1797 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Waterhouse A. M., Procter J. B., Martin D. M. A., Clamp M., Barton G. J., Jalview Version 2 - a multiple sequence alignment editor and analysis workbench. Bioinformatics 25, 1189–1191 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Drozdetskiy A., Cole C., Procter J., Barton G. J., JPred4: a protein secondary structure prediction server. Nucleic Acids Research 43, W389–W394 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cooper J. C., Phadnis N., Parallel Evolution of Sperm Hyper-Activation Ca2+ Channels. Genome Biology and Evolution 9, 1938–1949 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sandler L., Hiraizumi Y., Meiotic drive in natural populations of Drosophila melanogaster. ii. genetic variation at the segregation-distorter locus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 45, 1412–1422 (1959). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.