Abstract

Parkinson’s disease (PD) and other α-synucleinopathies are characterized by the accumulation of α-synuclein (αS) pathology that can spread via the cell-to-cell transmission of αS aggregates. To better understand how various brain cells contribute to the spreading of αS pathology, we examined the metabolism of αS aggreges or pre-formed fibrils (PFFs) in neuronal and glial cells (microglia, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes). In neurons, while the full-length αS rapidly disappeared following αS PFF uptake, truncated αS accumulated with a half-life of days rather than hours. Epitope mapping and fractionation studies indicate that αS PFF was truncated at the C-terminal region following uptake and remained insoluble/aggregated. In contrast, microglia and astrocytes rapidly metabolized αS PFF as the half-lives of αS PFF in these glial cells were <6 hours. Differential processing of αS by neurons was recapitulated in cell lines as differentiated CLU neuronal cell lines stably accumulate truncated αS while undifferentiated cells rapidly metabolize αS. Immunolocalization and subcellular fractionation studies show that internalized αS PFF is initially localized to endosomes followed by lysosomes. The lysosome is largely responsible for the degradation of internalized αS PFF as the inhibition of lysosomal function leads to the stabilization of αS in all cell types. Significantly, αS PFF causes lysosomal dysfunction in neurons. In summary, we show that neurons are inefficient in metabolizing internalized αS aggregates, partially because αS aggregates cause lysosomal dysfunction, potentially generating aggregation-prone truncated αS. In contrast, glial cells may protect neurons from αS aggregates by rapidly clearing αS aggregates.

Keywords: α-synuclein, α-synuclein fibril, Endosome, Lysosome, Neurodegeneration, Parkinson’s disease (PD), Proteolysis, trafficking, Truncation, Uptake

Introduction

Neurodegenerative diseases characterized by the presence of α-synuclein (αS) aggregates are classified as α-synucleinopathies, including Parkinson’s disease (PD) and Dementia with Lewy Bodies (DLB). In PD and DLB, progressive neurodegeneration is accompanied by the presence of cytoplasmic αS aggregates called Lewy bodies (LB) and Lewy neurites (LN) [1]. αS is a highly conserved protein consisting of 140 amino acids that is predominantly expressed in neurons and enriched in presynaptic terminals. Under pathological conditions, αS adopts β-sheet conformations stabilized in oligomeric and/or fibrillar structures [2,3]. A series of studies now establish that αS pathology can spread from cell-to-cell [4-8].

While the mechanistic details of cell-to-cell spreading of αS pathology are still being uncovered, the general view is that a donor cell releases αS oligomer/aggregates, and the neighboring recipient cell internalizes the αS aggregates. Once in the recipient cell, internalized αS is thought to induce aggregation of αS in the recipient cell, possibly by acting as a seed for further aggregation. Although the details of how αS aggregates ultimately template or induce aggregation of endogenous αS are not fully understood, the metabolism/degradation of exogenous αS by recipient cells is an important factor in the spreading of αS pathology. In this regard, studies show that exogenous αS is taken up via endocytosis and trafficked via the endo-lysosomal pathway [9]. Presumably, the αS is eventually degraded via the major proteolytic pathways in the cell, including autophagy-lysosome and ubiquitin-proteasome systems [10,11].

In addition, studies show that different cell types in the brain may differentially metabolize internalized αS. For example, astrocytes can protect neurons from αS toxicity by competing for uptake of extracellular αS and degrading αS, presumably in the lysosome [6]. Similarly, microglia may coordinately degrade internalized αS via tunneling nanotubes and lysosomes [12,13]. However, these studies use cells that are exposed to relatively large amounts of αS aggregates for long periods. Thus, how different neural cell types handle αS PFF immediately following uptake is not completely understood.

To better understand the contributions of various brain cell types in the spreading of αS pathology, we examined αS trafficking and metabolism at short time points following uptake in the major brain cell types (neurons, astrocytes, microglia, and oligodendrocytes). We show that microglia and astrocytes rapidly metabolize αS PFF where the half-lives of αS PFF in these glial cells are ~5 hours. In neurons, while the full-length αS rapidly disappears following αS PFF uptake, substantial amount of C-terminally truncated αS stably accumulates and persists for days. We also confirm that internalized αS PFF is trafficked to endosomes followed by lysosomes. In glial cells, lysosome can completely degrade internalized αS. In neurons, while αS PFF is trafficked to lysosomes but is not fully degraded. Collectively, our results show that different brain cell types differentially metabolize internalized αS PFF and that glial cells could attenuate cell-to-cell transmission of α-synucleinopathy by reducing available αS aggregates.

Materials and Methods

Primary cell culture:

Mouse pups between postnatal day 0-2 (P0-2) were used to establish primary cultures of cortical neurons and glia were established as previously described [14,15]. For Primary Cortical Neuron (PCN), dissociated cells from newborn mouse cortex were plated onto a Matrigel-coated cell culture dish using plating medium (PM; DMEM, 1 mM Sodium pyruvate, Glutamax, Penicillin-streptomycin and FBS) and on the followday, replaced with NbActiv4 (BrainBits LCC) containing FdU mitotic inhibitor (8 μM final) to halt the growth of non-neuronal cells. Culture media was changed periodically twice a week until the cells became mature neurons [~12 days in vitro (DIV)], and then started various treatments as indicated. For Mixed Glia culture, 12,000,000 dissociated cells from the newborn brain were plated on a Matrigel-coated T75 flask using PM. Media was changed twice in a week until the cells became confluent (~1 week in culture). Primary Microglial cultures were established from the confluent mixed glial culture in a T75 flask via shaking at 220 rpm, 37°C for 1 h. Floating microglia were pelleted by centrifugation (300×g for 5 min). The cells were resuspended in PM and filtered through a 70 μm cell strainer. Cells were plated for 48 hours before the experiment. Primary oligodendrocyte cultures were established from the mixed glial culture depleted of microglia. Following microglial depletion, media was replaced and placed on a shaker (220 rpm, 37°C, overnight). Floating oligodendrocytes were filtered using a 40 μm cell strainer and spun down at 200×g for 10 min. Cells were resuspended in OPC media (PM + 50 μg/ml apo-transferrin, 5 μg/ml insulin, 30 ηM sodium selenite, 10 ηM D-biotin, 10 ηM hydrocortisone, 20 ηg/ml PDGF-AA and 20 ηg/ml bFGF). Cells were plated for 7-10 days before the experiment. Primary Astrocyte cultures were established following the removal of microglia and oligodendrocytes from the T75 flask. The remaining attached cells, representing astrocytes, were washed twice with PBS and detached using 0.25% Trypsin-EDTA, 5 ml NbAstro media was added and filtered through a 40 μm cells strainer and spun down at 300×g for 10 min. The pellet was resuspended in NbAstro media and filtered through 70 and then 40 μm cells strainer. Counted and cells were plated at 800,000 or 400,000 cells per well for 2-4 days before the experiment for biochemical or immunocytochemical analysis, respectively.

Cell lines:

SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma, CLU198 mouse hippocampal neuronal cell lines, BV2 mouse microglia cell lines, and HEK-293 human embryonic kidney cell lines were used in this study. All these cells were growing on full medium (DMEM, 10% FBS and 1% Pen-Strep). For differentiation of SH-SY5Y full medium was exchanged with differentiation media containing Neurobasal-A, pen-strep, B27, and retinoic acid. And for CLU the differentiation media contained Neurobasal-A, pen-strep, B27, and glutamax. Cells were differentiated for at least one week before being used for experiments.

Generation of recombinant α-synuclein (αS) pre-formed fibril (PFF):

Recombinant wild-type human/mouse α-Synuclein (αS) isolation, purification, and fibril formation were done as previously described [16] with modifications (For protocol see: dx.doi.org/10.17504/protocols.io.81wgbxjx3lpk/v1)[14]. Purified αS monomers were used to assemble αS PFF by agitation as previously described [14]. The PFF was diluted in PBS to 5 μg/μl aliquot and kept in a −80°C freezer. For internalization and processing study, PFF from frozen stock was diluted to 0.25 μg/μl in PBS, sonicated (1 Sec “on” then 1 Sec “off’) for 120 Sec with 20% amplitude by utilizing a Fisher Scientific Branson micro probe-tip sonicator (Fischer Scientific; Hampton, NH). Then, the sonicated PFFs were added into the media for the indicated time and doses (4 μg/ml, if otherwise indicated) to study primary cortical neurons, primary microglia, primary astrocytes, primary oligodendrocytes, hippocampal cell line CLU, SHSY5Y and HEK cells.

α-synuclein (αS) preformed fibrils (PFF) uptake and degradation/clearance assays:

For the uptake assay, cells were treated with fresh cultured media containing 4 μg/ml of αS PFF and incubated for the indicated duration. Total lysates of fibril-treated cells were harvested at the end of the indicated time points.

For the clearance assay, cells were pretreated with 4 μg/ml of αS PFF for 2 h, then washed with PBS or PBS supplemented with trypsin (0.005%) for 1 min to remove any excess PFFs bound on the external cell surface. The washed cells were incubated with fresh media in the presence or absence of other drugs/inhibitors treatment. Cells were harvested at the indicated time points.

Subcellular lysosomal fractionation:

After the designated treatment, cells were washed thrice with DMEM and extracted in 0.5 ml of homogenization buffer (250 mM sucrose, 2 mM EDTA, 1.5 mM magnesium chloride, 10 mM potassium chloride, and 20 mM HEPES) supplemented with proteinase and phosphatase inhibitors. The cells were gently detached using a cell scraper and homogenized using a Teflon homogenizer (12 strokes). 50 μl of total homogenates (TH) were separated and lysed with TNE lysis buffer. The rest of the TH was centrifuged at 1000×g for 10 minutes at 4°C. The resulting supernatant was centrifuged for 20,000×g for 20 minutes at 4°C to collect the precipitate as a crude lysosomal fraction (CLF). The CLF was lysed with TNE lysis buffer and used for Western blot analysis.

Triton X-100 fractionation of soluble and insoluble αS:

Protein extraction and fractionation into total lysates (TL), Triton X-100 soluble (S), and Triton X-100 Insoluble (IS) fraction was conducted as described previously (For protocol see: dx.doi.org/10.17504/protocols.io.5qpvob21zl4o/v1)[14,17]. Briefly, cells were washed using cold PBS, TNE+1% TX-100 was added on ice for 5 mins and sonicated to achieve the TL fractions. The TL was centrifuged on the Airfuge (Beckman Coulter) at 100,000xg for 10 minutes. The supernatant was adjusted to complete TNE lysis buffer and considered as a soluble fraction. Washed pellets were re-suspended in complete TNE lysis buffer as the insoluble fractions.

Protein extraction and Immunoblot analysis of protein expression:

Cells were lysed in TNE lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA adjusted to pH at 7.4) containing 1% SDS, 0.5% NP-40, 0.5% DOC and protease/phosphatase inhibitors as previously described (For protocol see: dx.doi.org/10.17504/protocols.io.3byl4qpqjvo5/v1)[10]. Immunoblot analysis was conducted as described previously [10,14,18]. Briefly, relative protein levels of Total αS (SYN-1), Hu Specific αS, NAC-2 αS, N-2 αS, p62, LC3 and other proteins were determined from cell extracts by quantitative immunoblots analysis using chemiluminescence detection of horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies on the GE Image-Quant LAS-4010 (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI). Image-Quant software (GE) was used to determine the intensity of the immunoreactive bands [10,14,18].

Labeling of α-synuclein pre-formed fibril with Alex-Fluor 488 (PFFs-AF-488):

Alex Fluor 488 Microscale Protein Labelling Kit (AF-488, A30006) (Invitrogen) was used to label PFFs according to the manufacturer’s protocol. AF-488 reactive dye has a tetrafluorophenyl (TFP) ester moiety that is more stable in solution than the commonly used succinimidyl (NHS) ester. TFP ester reacts efficiently with primary amines of protein to form a stable dye-protein conjugate and is independent of pH between 4 and 10. Hu-WT-~S fibrils (PFFs) were diluted at a concentration of 1μg/μL in PBS followed by sonication (1 Sec on then 1 Sec off) for 120 Sec with 20% amplitude. Sonicated PFFs were used to label with AF-488.

Immunocytochemistry:

Immunocytochemistry was conducted as described previously [10,14,15]. Briefly, cells grown on coverslips were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) and immunostained followed by confocal imaging. Alex fluor (AF-647 or AF-488) conjugated secondary antibody was used.

Analysis of Lysosome Function:

To measure lysosomal Cathepsin B activity in live cells, we used the Magic Red Fluorescent Cathepsin B assay kit (Immunochemistry Technologies, CA). Briefly, cells were plated on coverslips and following PFF-488 uptake for indicated times, the cells were washed [PBS/trypsin (0.01%)] and treated with 1x Magic Red solution for 15 minutes at 37°C per manufacturer instruction. Live cell confocal imaging was done immediately by confocal microscopy where the lysosomal Cathepsin B activity is indicated by red fluorescence puncta produced by the hydrolysis of fluorogenic substrate, Magic Red. Images were taken from each culture using identical conditions and the confocal images were used to analyze the Magic Red signal in each cell using Image J. Briefly, each cell was outlined and the % area of the cell covered by Magic Red signal, as well as total signal intensity per cell, was determined.

To measure lysosomal membrane permeabilization (LMP), we immunostained for Galactin-3 (Gal3) [19]. Gal3 is a sugar-binding protein that translocates from cytosol to lysosome when the membrane becomes permeable due to lysosomal damage. Once LMP happens, the Gal3 fluorescence pattern changes from a diffuse condition to a dotted punctate structure. For the LMP assay, cells were plated on coverslips and treated with PFF-488 as indicated time. Cells were fixed in 4% PFA and immunostained using Gal3 primary and AF-647 conjugated secondary antibodies. Images were taken by confocal microscopy. To measure Gal3 accumulation in permeable lysosomes, punctate Gal3 staining was determined using Image J. Briefly, each cell was outlined and the % area of the cell covered by Gal3 immunoreactivity, as well as total signal intensity per cell, was determined.

To measure overall lysosomal function in PCN, we used the DQ-Red-BSA assay. Briefly, cells were cultured and treated with PFF-488 as mentioned above. Following indicated treatments, 10 μg/ml of DQ-BSA Red (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was dissolved in cell culture media and incubated for the last 90 minutes at 37°C. Fixed cells using 4% PFA at room temperature and images were taken following identical conditions throughout the treatment condition. DQ-BSA Red fluorescent signal is detected only when the fluorogenic substrate is hydrolyzed by lysosomal proteases. The red fluorescence resulting from lysosomal targeting of DQ-Red-BSA was determined using Image J. Because of an extensive network of neurites with DQ-Red signal in neurons, we quantified total DQ-Red signal (% area covered and total signal intensity) per microscopic field in at least 4 independent areas. The total % area covered by the DQ-Red signal was divided by the number of cells (DAPI stained nuclei) in the field analyzed.

Antibodies:

The primary antibodies used in this study is listed in the supplementary table (Table S1).

Statistical analysis:

To test for statistical significance between treatment groups, data was analyzed by one-way or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by a Multiple Comparison post hoc test (Tukey’s/Dunnett’s/Bonferroni’s), or Student’s t-test. All tests were performed using GraphPad PRISM Software (Version 10). All the data are expressed as means ± S.E. Probability (p) values less than 0.05 were considered significantly different.

Results

Exogenous αS fibrils accumulate as a truncated species in neurons.

While neurons internalize both exogenous αS monomers and fibrils, information regarding how neurons metabolize αS monomers and fibrils following intracellular uptake is incomplete. Thus, we treated primary cultures of cortical neurons with human αS monomers and αS preformed fibrils (PFF) to study the kinetics of intracellular αS metabolism. To minimize the impact of continuous uptake of exogenous αS in the culture media in the analysis of αS metabolism, we removed exogenous αS after 2h of uptake period. Briefly, the neurons were transiently exposed to exogenous αS for 2h and then washed with PBS with and without trypsin-EDTA to remove any excess PFFs attached to the outer membrane of neurons (Fig. S1). The amount of residual αS following PBS wash was comparable to the cells washed with PBS containing Trypsin, which proteolyzes any residual αS attached to the outer membrane of neurons. Thus, the majority (~90%) of the remaining αS following the PBS wash represents internalized αS as they were resistant to the trypsin wash (Fig. S1).

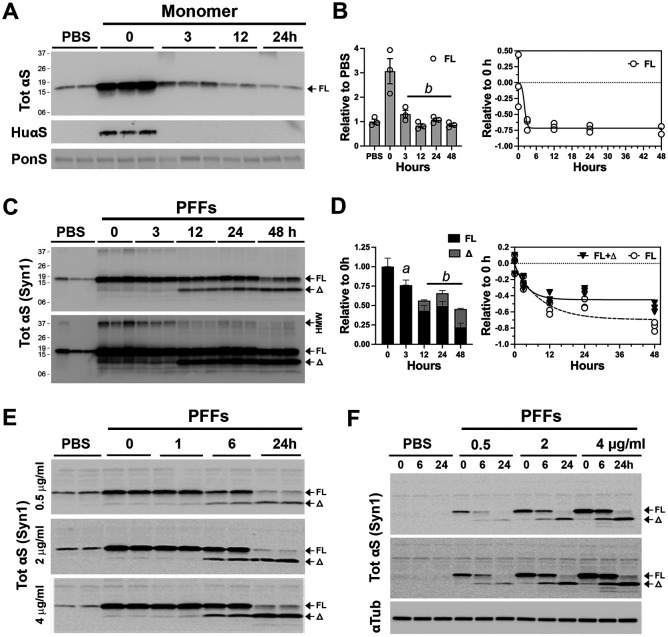

In neurons treated with αS monomers, the transient increase in total αS level rapidly decreases to the endogenous αS levels within 3 hours (Fig. 1A and B). Immunoblot analysis for the exogenous human αS, using the anti-HuαS antibody [17], confirms the rapid loss of human αS monomer in neurons (Fig. 1A). In neurons treated with αS PFF, internalized αS persists for a much longer period, with the approximate half-life of 12 hours for the full-length αS (αSFL) (Fig. 1 C, D), indicating that the internalized αS PFF is more stable than the αS monomer. Significantly, αS PFF treatment led to the appearance of truncated αS (αSΔ) metabolites with a major species resolving at ~10kDa (αS10) and corresponded to the disappearance of aSFL (Fig. 1C and D). Significantly, αSΔ stably remains even after 48 hours (Fig. 1C and D). Finally, αS PFF treatment leads to the stable accumulation of high molecular weight (HMW) SDS-resistant αS oligomers with major Syn-1 reactive species resolving at ~37kDa (Fig. 1C, lower panel). These results show that while neurons can rapidly degrade internalized αS monomers, internalized αS aggregates remain stable for a prolonged period. We note that “pulsing” αS PFF exposure by removing uninternalized αS PFF is important for accurate determination of αS PFF metabolism as neurons in unwashed cultures continue to internalize more αS PFF over time (Fig. S1D)

Figure 1. Exogenous αS pre-formed fibril stably accumulates as a truncated variant in primary cortical neurons.

Primary cortical neurons (PCN) cultured from newborn C57BL6/J mouse brains at 7 days in vitro (DIV) were used. PCN were pre-incubated with 4 μg/ml (unless otherwise indicated) (A, B) monomeric αS or (C-F) αS PFF for 2h and washed to removed extracellular αS or αS PFF that was not internalized. Cells were provided with fresh media and then incubated for the indicated time before harvesting. A) Following αS monomer treatment, cell lysates were immunoblotted for total (Tot) αS or Hu-αS. Equal loading of proteins was verified using total protein stain (Ponceau S, PonS). B) Quantitative analysis of TotαS immunoblot shows that internalized αS monomers are rapidly metabolized within 3 hours of internalization. Mean±SEM; n=3. b, p<0.001 vs 0-hour, One-way ANOVA. C) Immunoblot analyses for TotαS following PFF treatment show that internalized full-length (FL) αS is truncated (Δ) and stably accumulate as the truncated species. Shown are two different exposure levels to show details. D) Quantitative analysis of TotαS immunoblot in (C). Bar and line graph show the kinetics of degradation and accumulation of αS species over time. Mean±SEM; n=3. a, p<0.01; b, p<0.001 vs. total αS (FL+Δ) at 0-hour, One-way ANOVA. E) To determine if the amount of αS PFFs internalized impacts the truncation and/or stability of internalized αS PFFs, PCN was treated with 0.5-, 2-, and 4-μg/ml of αS PFF and the status of TotαS was analyzed at indicated times. Even at very low amounts of PFFs (0.5 μg/ml), internalized PFFs are rapidly truncated and stably accumulate. F) To determine if endogenous αS impacts the metabolism of internalized αS PFFs PCN established from αS KO mice were treated with αS PFFs. The results show that the lack of endogenous αS does not impact the metabolism of internalized αS PFFs. Shown are two different exposures for TotalαS to show details. Equal loading of proteins was verified by immunoblotting for α-tubulin (αTub).

Because large amounts of internalized αS PFF may overload the cellular trafficking and degradation system, we asked whether the truncation and stability of internalized αS PFF depended on the amounts of αS PFF internalized. Cultured neurons were treated with 0.5, 2, or 4 μg/ml of αS PFF and the status of internalized αS was analyzed at various time following the PFF treatment (Fig. 1E). Our results show that even in neurons exposed to the lowest amount of αS PFF (0.5 μg/ml, ~30 ηM), internalized αS PFF stably accumulates as truncated species with similar kinetics to neurons treated with larger amounts of αS PFF (Fig. 1E). Thus, generation and accumulation of truncated αS is an intrinsic property of αS PFF metabolism in neurons rather than a secondary effect of αS PFF overloading the protein degradation system. We also determined if endogenous αS expression impacts the metabolism of exogenous αS PFF by treating cortical neurons lacking αS expression, established from αSKO mice, with αS PFF (Fig. 1F). Comparison with the wildtype (WT) mouse neuron (Fig. 1E) showed that αS PFF is identically metabolized in both WT and αSKO neurons.

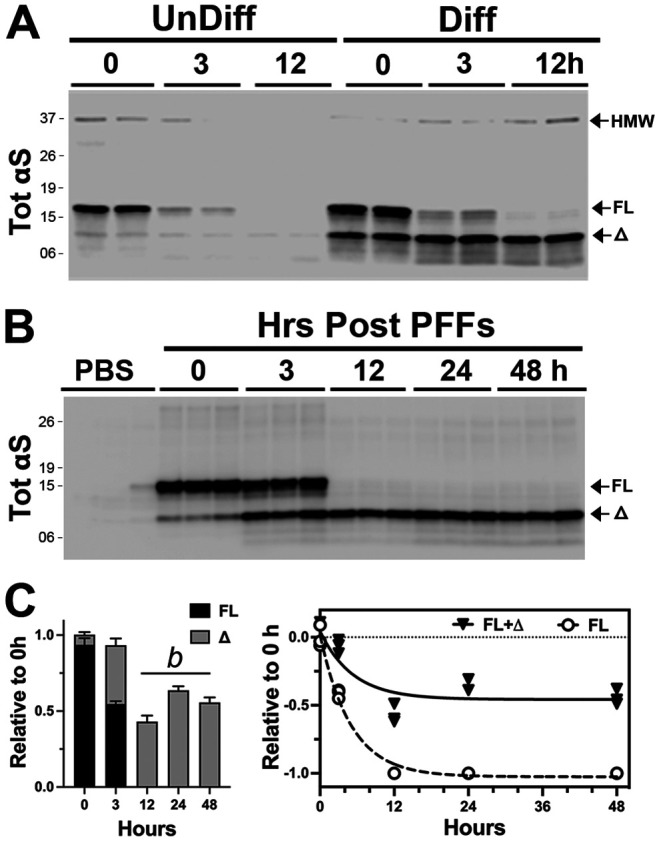

We previously showed that in neuronal cell lines and neurons, αS turnover slows with neuronal differentiation and maturation [20]. Thus, we examined whether neuronal differentiation impacts the metabolism of internalized αS PFF. For this study, we used the mouse embryonic hippocampal cell line (CLU198) that can be induced to differentiate into neuronal phenotype [21] and can efficiently internalize αS PFF (Fig. S1C). In undifferentiated CLU198 cells, internalized αS PFF, including the HMW species, disappears rapidly (half-life of <3 h) with no intermediate accumulation of αSΔ species (Fig. 2A). In contrast, in neuronally differentiated CLU198 cells, the disappearance of αSFL was accompanied by the stable accumulation of HMW αS and ΔSΔ species (Fig 2A-C), even at 48h following uptake (Fig 2B, C). Thus, the metabolism of αS PFF in neuronally differentiated CLU198 neuroblastoma cells was very similar to that seen in primary neurons (Figs. 1C, D; 2B, C). Analysis of αS PFF metabolism in a human neuroblastoma cell line (SH-SY5Y cells) (Fig. S1E) showed a similar pattern of αS metabolism as seen in CLU198 cells. Undifferentiated SH-SY5Y cells efficiently degraded αS PFF while in differentiated SH-SY5Y cells, internalized αS PFF stably accumulated as αSΔ species (Fig. S1E). Collectively, our results confirm that neuronal differentiation and maturation are associated with the distinct metabolism of αS PFF where the αSFL is rapidly processed and αS stably accumulates as αSD species.

Figure 2. Internalized αS PFFs is differentially metabolized in undifferentiated and differentiated neuronal cells.

(A) Undifferentiated (left) or neuronally differentiated (right) hippocampal cell line (CLU198) were treated with 4 μg/ml αS PFF and internalized αS PFF were analyzed at 0-, 3-, and 12-h following removal of excess αS PFF. In undifferentiated cells, internalized αS PFF is rapidly degraded by 12 h while truncated αS stably accumulates in differentiated cells. (B) Neuronally differentiated CLU198 cells were treated with αS PFF and internalized TotαS levels were analyzed at indicated times following the wash. The immunoblot analysis for TotαS clearly shows the rapid appearance and stable accumulation of truncated αS (Δ). C) Quantitative analysis of immunoblot shown in (B). The bar graph shows the relative status of full-length (FL) and truncated (Δ) αS levels over time, confirming the stable accumulation of truncated αS. Mean±SEM; n=3. b, p<0.001 vs total αS (FL+Δ) at 0-hour, One-way ANOVA.

Internalized αS PFF is rapidly cleared by astrocytes and microglia but not oligodendrocytes.

The differences in αS PFF metabolism between undifferentiated and differentiated neuronal states in the cell lines raise the possibility that glial cells in the brain may be more efficient in metabolizing internalized αS PFF than neurons. Thus, we examined the clearance/metabolism of αS PFF in primary cultures of microglia, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes. We determined the purity of the cell types in cultures by immunohistochemical analysis for the cell type markers (Fig. S2A). As with neurons (Fig. S1), analysis of cells washed with trypsin following 2h exposure to αS PFF showed all cell types internalized αS PFF (Fig. S2B).

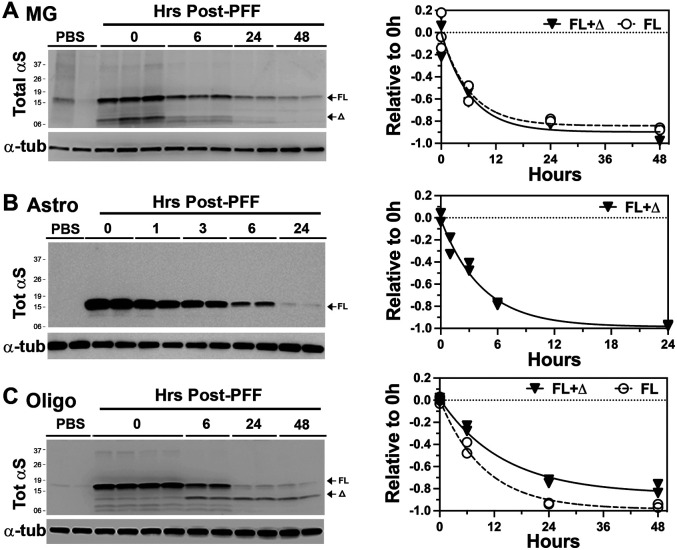

To define the clearance of internalized αS PFF, the cell lysates were collected at different times following the wash and analyzed for internalized αS. Our results show that both microglia and astrocytes efficiently metabolized αS PFF with the approximate half-life of 6h for microglia and 3h for astrocytes (Fig. 3A, B). Further, no obvious accumulation of αSΔ occurs in either of the cell types (Fig. 3A, B). Analysis of human embryonic kidney cell line, HEK293 showed that, like the other non-neuronal cells, the HEK293 cells efficiently degraded the internalized αS PFF (Fig. S2C).

Figure 3. Glial cells rapidly degrade internalized αS PFF.

(A) Primary microglia (MG), (B) Primary astrocyte (Astro), and (C) Primary oligodendrocyte (Oligo) cultures were established from newborn C57BL/6 mouse brains. Cells were pre-incubated with 4 μg/ml αS PFF, harvested at indicated times post-washing, and immunoblotted for TotαS. α-tubulin (αTub) was used as a loading control. Quantitative analysis of the immunoblots (Graphs) shows the rate of decrease in TotαS. Note that most of the internalized αS PFFs are degraded within 12-24 h with a much shorter half-life (~6 hours) than in neurons. Further, astrocytes and microglia do not accumulate truncated αS seen in neurons. Significantly, oligodendrocytes stably accumulate truncated αS (Δ), albeit at lower levels than in neurons. Mean±SEM; n=2 per time point.

Significantly, primary oligodendrocytes show distinct αS PFF metabolism compared to the other glial cell types. While the oligodendrocytes rapidly metabolized αSFL, with a half-life of ~6h, oligodendrocytes also generated αSΔ with MW of ~10 kDa that remained stable for a prolonged period (Fig. 3C). Thus, the oligodendrocytes resemble neurons in the metabolism of αS PFF by generating and accumulating αSΔ .

Thus far, our results show that microglia and astrocytes efficiently internalized and degraded αS PFF. However, neurons and oligodendrocytes did not fully metabolize αS PFF as αSD accumulated in these cells. While accumulation of αSD in αS PFF-treated neurons has been reported [22], this report is first to show that non-neuronal cells do not accumulate αSΔ and that oligodendrocytes also accumulate αSΔ following internalization of αS PFF. It is significant that both neurons and oligodendrocytes exhibit similar metabolism of internalized αS PFF as these are the two major cell types known to develop α-synuclein pathology in brain [23-25].

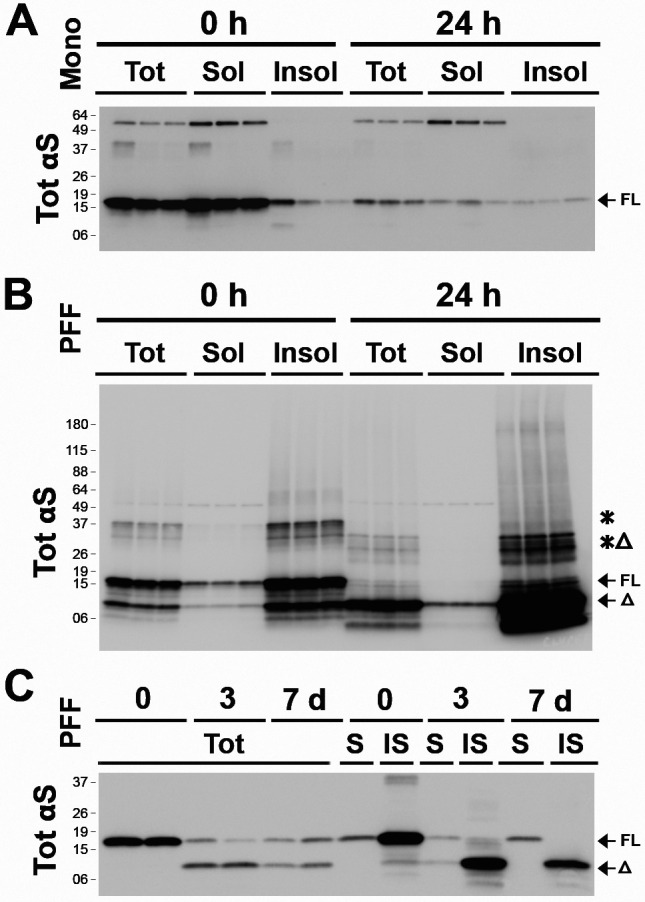

Internalized αS PFF and truncated αS remain detergent insoluble in neuronal cells.

When αS PFF are sonicated to facilitate uptake by the cells, sonication leads to a significant fraction of αS PFF partitioning into buffer soluble fractions that can induce seeding of αS aggregates [26]. Our analysis also confirmed that sonicated αS PFF used to induce αS pathology contained a significant amount of soluble αS (data not shown). Thus, we asked if the internalized αS are soluble or insoluble as they are metabolized by neurons. First, we compared the solubility of monomeric αS and αS PFF internalized by differentiated CLU198 cells (Fig. 4A, B). CLU198 cells were treated with αS monomer (Fig. 4A) or αS PFFs (Fig. 4B) for 2 h, washed, and the cells were collected at ‘0h’ and ‘24h’. The collected samples were solubilized in triton X-100 (TX-100) and the detergent soluble and insoluble fractions were obtained by centrifugation at 100,000xg. In the monomer-treated cells, the majority of αS remained soluble at 0h and degraded by 24 h, albeit a small fraction of αS monomer, likely endogenous αS, was found in the insoluble fraction at 24 h. In the αS PFF-treated cells, the majority of αS species partitioned to the TX-100 insoluble fraction, even at 24 h. Significantly, TX-100 insoluble SDS-resistant αS oligomers resolving ~37 kDa at 0h (Fig. 4B, *) resolved at slightly lower MW at 24h (Fig. 4B, *Δ), consistent with the truncation of the HMW αS species.

Figure 4. Internalized αS PFF and truncated αS remain detergent-insoluble.

(A, B) Neuronally differentiated CLU198 cells were treated with 4 ug/ml of αS monomers (A) or αS PFF (B). At 0h and 24h after washing, the cell lysates were fractionated into total SDS-soluble lysates (Tot), Triton X-100 (TX-100) soluble (Sol) fraction, and TX-100 insoluble (Insol) fraction. Immunoblot analysis show that internalized αS monomers partition with the TX-100 Sol fraction (A) while bulk of αS PFF partitions with the TX-100 Insol fraction (B). (C) PCN treated with PFFs were analyzed for TotαS in TX-100 soluble (S) and insoluble (IS) fractions at 3- and 7-days post αS PFF treatment. Even at 7 days following the initial internalization of αS PFF, virtually all of the truncated αS (Δ) partitions with the insoluble fraction.

Analysis of soluble and insoluble αS in the αS PFF-treated PCN during several days following PFF treatment show that the internalized αS remained insoluble at 0 day, 3 days, and 7 days following initial αS PFF internalization (Fig. 4C). Consistent with very slow turnover of internalized αS PFF in neurons, ~50% of αS remains even at 7 days post internalization.

Neurons accumulate C-terminally truncated αS PFF.

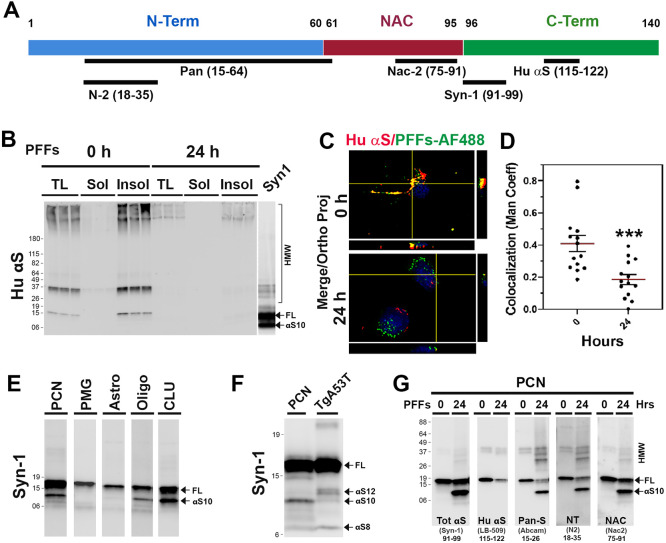

We previously showed that αS is normally truncated at C-terminus and that C-terminally truncated αS is enriched in αS aggregates in vivo [17]. To determine if internalized αS PFF is C-terminally truncated in neurons, we performed immunoblot analysis of the soluble and insoluble fractions from PFF-treated CLU198 cells using the anti-HuαS antibody [17] that selectively recognize the HuαS C-terminal epitope (amino acids 115-122) (Fig. 5A). Our results show that HuαSyn antibody recognized both HMW and αSFL at 0h but the HuαS immunoreactivity was virtually absent at 24 h (Fig 5B). Taken together with immunoblot analysis of the αS species detected by Syn-1 antibody (Figs. 2B, 4B), we conclude that the majority of internalized αS PFF was C-terminally truncated at 24 h. We also analyzed αS PFF-treated PCN at various times and compared the αS variants recognized by Syn-1 and anti-HuSyn antibodies (Fig. S3A). As with the CLU198 cells, HuαSyn reactive bands disappeared with the loss of αSFL, indicating that the αSD species were missing the C-terminal portion of the protein.

Figure 5. Neurons accumulate C-terminally truncated αS PFF.

(A) Schematic representation of αS with the locations of epitopes for the anti-αS antibodies used to map the truncated αS. (B) TX-100 soluble (Sol) and insoluble (Insol) fractions from PFFs treated CLU198 cells, shown in Figure 4B, were immunoblotted using HuαS antibody. Note that HuαS antibody recognizes αS FL but not the truncated αS resolving at ~10 kDa (αS10). (C) Neuronally differentiated CLU198 cells were treated for 2h with Alex Fluor 488 (PFFs-AF 488) labelled PFFs and washed to remove any extracellular PFFs-AF-488. Cells were provided with fresh media and then incubated for 0h or 24h prior to fixing and immunostained with HuαS antibody. Double immunofluorescence microscopy was used to visualize HuαS (red) and PFFs-AF 488 (green). (D) Co-localization (yellow) between Hu αS and PFFs-AF 488 were quantified (n=15-18 cells) by using the Manders’ coefficient (ImageJ software) and plotted. ***p<0.001, Unpaired t-test. (E) PFFs treated PCN, primary microglia (PMG), primary astrocytes (Astro), oligodendrocytes (Oligo), and neuronal differentiated CLU198 cells (CLU) were analyzed for αS variants. All the samples were resolved on same gel but separated and reordered for clarity. Only PCN, Oligo, and CLU accumulate αS10. (F) Comparison of αS variants in αS PFF-treated PCN and TgA53T mice with αS pathology. While αS12 is the major truncated αS variant in TgA53T mice, αS10 is the dominant variant produced from internalized αS PFF in PCN. (G) Triton X-100 (TX-100) insoluble fractions from PCN were immunoblot analyzed for Tot αS (SYN-1, epitope 91-99), C-terminal HuαS (epitope 115-122), N-terminal Pan-S (epitope 15-26), N-terminal NT-αS (epitope 18-35) and NAC-domain containing NAC-2αS (epitope 75-91). αS10 is missing the C-terminal HuαS epitope but retains the N-terminal epitopes.

To document the C-terminal truncation at the cellular level, neuronally differentiated CLU198 cells were treated with αS PFF labeled with Alex Fluor-488 (AF-488, green) and immunostained for HuαS and visualized using AF-647 conjugated secondary antibody, at 0 h and 24 h following αS PFF treatment (Fig. 5C, D). Colocalization of AF-488 (Green) with HuαSyn immunoreactivity (Red) showed high levels of colocalization between AF-488 and HuαS at 0 h. However, at 24 h following αS PFF treatment, colocalization of AF-488 with HuαS dramatically decreased, indicating that the C-terminal portion of the αS was missing from the internalized PFF at 24 h (Fig. 5C, D).

To further define the nature of the αS truncation, we used a variety of αS antibodies with the defined epitopes (Fig. 5A) to map the primary structure of αS species generated by the cells following αS PFF internalization. Immunoblot analysis with Syn-1 antibody (amino acids 91-99) [17,27] (Fig. 5E) showed that in PCN, CLU198, and oligodendrocytes, αS PFF treatment resulted in a major truncated αS species at ~10 kDa (αS10), while the accumulation of truncated αS species were not obvious in PMG and astrocytes (Fig. 5E). While small amount of αSΔ was occasionally seen in PMG, these species were transient as they disappeared with the full-length αS (αSFL) (Fig. 3A). To determine if the αSΔ seen in PFF treated neurons accumulate in vivo with αS pathology, we also compared the PFF-derived αS with the insoluble αS from the transgenic mouse expressing A53T mutant human αS (TgA53T) affected by α-synucleinopathy (Fig. 5F). Insoluble aggregate recovered from TgA53T is qualitatively similar to the aggregates recovered from human PD cases [17]. Comparison of TgA53T lysate with αS PFF treated neurons show that αSΔ resulting from internalized αS PFF is qualitatively different from the insoluble αS aggregates recovered from the TgA53T mouse. Specifically, the major truncated species in the TgA53T mouse model resolves at ~12 kDa (αS12), while in αS PFF-treated neurons, αS12 was not seen and αS10 was most abundant. Because αS aggregates in vivo contain both N- and C-terminally truncated αS [17], we used additional anti-αS antibodies with defined epitopes located at the N-terminal region, C-terminal region, and central-NAC regions (Fig. 5A) to map the αSΔ species inαS PFF-treated PCN (Fig. 5G). The results show that the αSFL reacts with all antibodies. The major 10 kDa truncated αS (αS10) reacted to antibodies recognizing the N-terminal (N2, pan-Syn) and the central (NAC, Syn-1) epitopes but not to the antibodies that bind to the C-terminal epitopes (HuαS, LB509). The minor truncated variants at ~6 kDa only reacted to antibodies to central epitopes (Syn-1, NAC). Thus, internalized PFF was first truncated at the C-terminal region to generate 10 kDa species (αS10) and further truncated to remove the N-terminal region (αS8). In contrast, insoluble αS from TgA53T model contains a major C-terminally truncated species at ~12 kDa (αS12), a minor C-terminal species 10 kDa species (αS10), and another prominent truncated species at ~6-8 kDa lacking both N- and C-terminal regions (αS8) (Fig. 5F). Our comparative analysis shows that both αS10 and αS8 maybe common species in both PFF treated PCN and TgA53T mice (Fig. 5F). Our results are consistent with previous results showing that αS12 is derived from truncation of endogenous αS monomers while the αS10 and αS8 are only seen in the insoluble aggregate fractions [17,28,29].

Epitope mapping of αS species in primary oligodendrocytes (Fig. S3B) and hippocampal CLU198 cell lines (Fig. S3C) show that these cells accumulated of αS10 where C-terminal epitope was missing while retaining the N-terminal and NAC regions. In PMG, a truncated species at ~6 kDa (αS6), missing both N- and C-terminal region is observed. Our results show that the accumulation of C-terminally truncated αS is a common feature of neuronal cells (PCN and CLU198 cells) and the oligodendrocytes, cell types that are associated with α-synucleinopathies.

Internalized αS PFF is trafficked to lysosomes via endosomes.

Internalization of αS PFF occurs via the endosomal pathway and is trafficked to lysosomes [4,30-32]. Further, lysosomal proteases, such as cathepsins and asparagine endopeptidase (AEP), are implicated in the C-terminal truncation of αS [29,33,34]. Thus, we determined the time course of intracellular trafficking of αS PFF immediately after the internalization by treating the cells with αS PFF labeled with Alex Fluor-488 or −647 (AF-488 or AF-647).

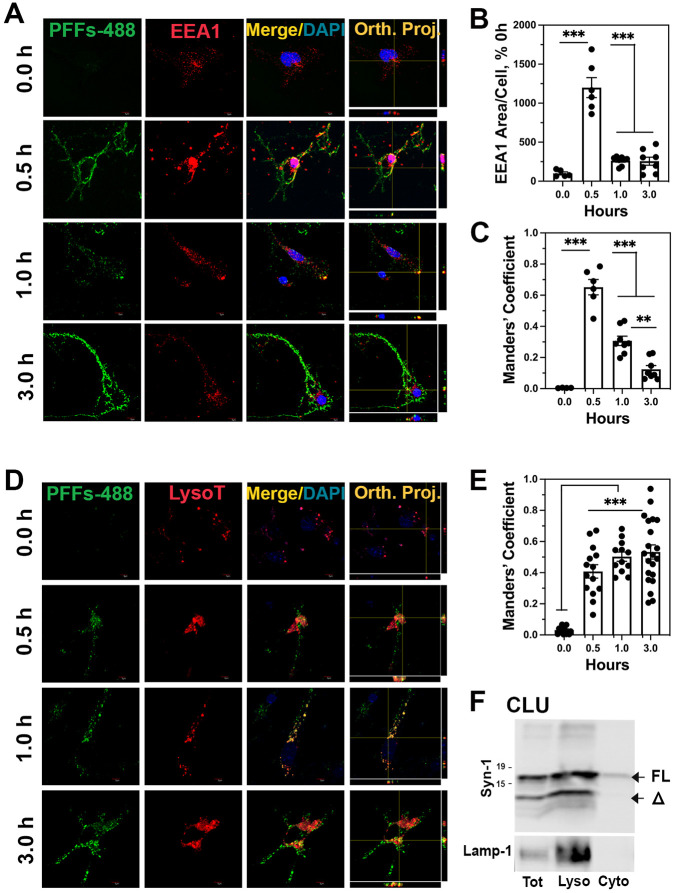

To confirm that internalized αS PFF in neurons are initially trafficked to endosomes, we colocalized internalized PFF-AF488 with an early endosome marker, EEA1, at different times following PFF-AF488 treatment (Fig. 6 A-C). At 0.5h post αS PFF treatment, a significant increase in the amount of EEA1 staining was seen compared to the levels of EEA1 staining at other times (Fig. 6A and B), indicating that internalization of αS PFF induced an increase in early endosomes. A strong co-localization of PFF-AF488 with EEA1 was seen at 0.5 h and the colocalization decreased at 1 h and 3 h post αS PFF treatment (Fig. 6A and C). Following transit through endosomes, we hypothesize that a decrease in endosomal αS represents the trafficking of internalized αS PFF to lysosomes. To confirm this, we first treated PCN with the Lysotracker Red-50 followed by transient exposure to PFF-AF488. Colocalization of the PFF-AF488 with the Lysotracker was examined at 0, 0.5, 1.0, and 3.0 h post-PFF treatment (Fig. 6D and E). Our results show that as the PFF-AF488 exits the endosomal compartment, PFF-AF488 accumulates in the lysosomes labeled by the Lysotracker (Fig. 6D and E). We also performed subcellular fractionation to obtain Lamp1-enriched lysosomal fraction and cytosolic fraction from PFF-treated CLU198 cells (Fig. 6F). Immunoblot analysis for αS showed that most of the αS, both αSFL and αSΔ, is recovered with the lysosomal fractions.

Figure 6. αS PFF is internalized via endosomes and trafficked to lysosomes.

PCN was treated with PFF-AF488 and fixed at 0-, 0.5-, 1- and 3-h following PFF-AF488 addition. (A) Cells were immunostained for early endosome marker EEA1. Both EEA1 (Red) and αS PFF-AF488 (Green) were imaged by double immunofluorescence microscopy. (B) Quantitative analysis of the area/cell covered by EEA1 shows transient increase in early endosomes immediately following αS PFF uptake. (C) Colocalization of EEA1 with PFF-AF488, expressed as the Manders’ coefficient, show initial colocalization of EEA1 and PFF-AF488 followed by a progressive decrease in colocalization. (D) PCN treated with PFF-AF488 were labeled with Lysotracker Red (LysoT). Both PFF-AF488 (Green) and LysoT (Red) were imaged using double immunofluorescence microscopy. (E) Colocalization of PFFs-AF488 with LysoT, expressed as the Manders’ coefficient, shows that PFFs-AF488 is trafficked to lysosomes and continues to accumulate with lysosomes over time. (F) Differentiated CLU-198 cells were treated with PFFs for 30 minutes and cytosolic and lysosome-enriched fractions were obtained. Immunoblot analysis of the fractions shows that both αS-FL and αS10 partitions with the lysosome fraction. The fractions were also immunoblotted for Lamp1, a lysosomal marker. **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, One-way ANOVA.

Analysis of PFF-AF488 with other subcellular markers in PCN show some co-localization of αS PFF-AF488 with Lamp-2, p62, and endoplasmic reticulum marker, Grp78 (Fig. S4A). No significant colocalization of internalized PFF-AF488 are seen with the markers of autophagosomes (LC3) or Golgi (GM-130) (Fig. S4A). Analysis of PMG and astrocytes (Fig. S4B and C), show that internalized AF488-PFF initially co-localizes with the endosome markers followed by the lysosome markers.

Collectively, our results support the scenario where internalized αS PFF traffic to lysosomes via the endosomes. Further, we proposed that the truncation of αS PFF (neurons) and/or degradation of αS PFF (all cells) occurs in lysosomes. In neuronal cells, internalized αS PFFs stably accumulated in the lysosomes (Fig. 6D-F) and the time course of αS PFF colocalization of lysosomes mirrors the timer course of αSΔ accumulation (see Fig. 1C and E).

Lysosome is the major degradation machinery of αS PFF

Lysosome is an acidic organelle containing hydrolytic enzymes that are responsible for the degradation of protein aggregates, non-functioning intracellular organelles, and foreign influx [10,35]. Given that the lysosome is the predominant destination of internalized αS PFF, we hypothesize that the lysosome is responsible for the rapid metabolism of αS PFF in non-neuronal cells. To directly test the role of lysosomes in αS PFF metabolism, we used bafilomycin A1 (Baf), which inhibits v-ATPase responsible for the acidification of lysosomes. This lysosomal acidification requires the activation of resident hydrolytic enzymes to stay inside the lysosome [36].

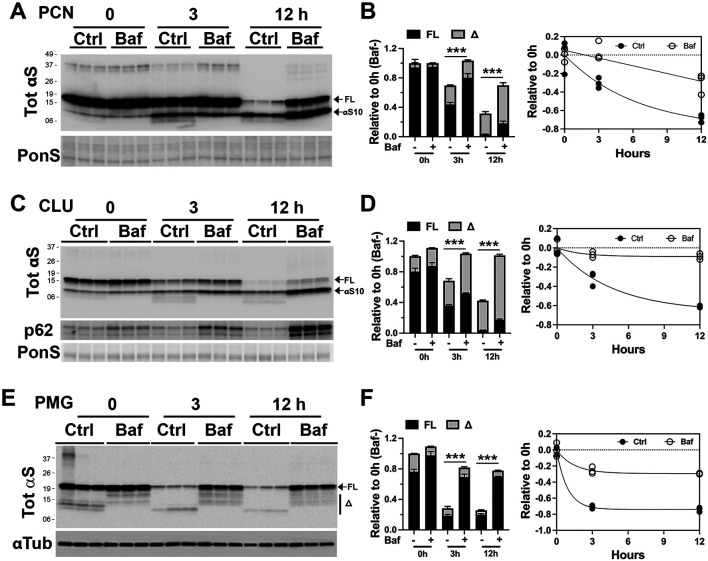

Baf inhibition of lysosome in αS PFF-treated PCN resulted in stabilization of both αSFL and αSΔC, particularly at 12 h post-PFF treatment (Fig. 7A and B). In CLU-198 cells, Baf also caused αS stabilization as in PCN (Fig. 7 C and D). Because CLU198 cells exhibit a faster rate of αS PFF truncations, increased levels of both αSFL and αS10 with Baf treatment were obvious at 3 h following αS PFF uptake. Analysis of Triton X-100 soluble and insoluble fractions showed that the Baf treatment increased αS in the insoluble fraction (Fig. S5A). Further, both monomeric αS and HMW αS were stabilized by Baf treatment (Fig. S5A).

Figure 7. Inhibition of Lysosome function dramatically slows the degradation of αS PFF in neuron and glial cells.

Primary neuronal culture (PCN) (A, B), neuronally differentiated CLU198 cells (C, D), and Primary Microglia (PMG) (E, F) were pretreated with a lysosomal inhibitor bafilomycin A1 (100 ηM, Baf) or DMSO for 4h. During the last 2 h of Baf treatment, 4 μg/ml of αS PFF was added to the cells. The cells were washed and provided with fresh media containing DMSO (control, Ctrl) or Baf (100 ηM) and harvested at 0-, 3- and 12-h of incubation in fresh media. The levels of TotαS at each time point were determined by immunoblot analysis. Ponceau S (PonS) or αTub was used as loading controls. Bar graphs show that levels of total αS (FL+α) in Baf-treated cells are significantly higher than in controls. Further, the individual levels of FL and truncated αS (αS10, α) are significantly higher in Baf-treated cells at 12 h compared to the corresponding controls (p<0.001, Two-way ANOVA). The line graph and corresponding regression analysis show that Baf treatment significantly slows rate of αS degradation. Mean±SEM; n=3. ***p<0.001, total αS(FL+α) in Baf− vs Baf+, Two-way ANOVA.

The above results indicate that in neuronal cells, αS PFF is largely metabolized by lysosomes. Significantly, while αSΔC seems to accumulate in the lysosomes, inhibition of lysosomes by Baf does not inhibit αS truncation. Thus, while the truncated αS PFF accumulates in lysosomes, the truncation of αS PFF is independent of αS degradation.

We also treated non-neuronal cells with Baf to test if lysosome function is responsible for the effective degradation of internalized αS PFF. Results from PMG (Fig. 7E and F) show that Baf treatment leads to robust stabilization of αS PFF. Similarly, Baf treatment also prevents degradation of αS PFFs in primary astrocytes and HEK293 cells (Fig. S5 B and C). Thus, our results show that in both neuronal and non-neuronal cells, lysosomal degradation is the predominant mode of degradation for internalized αS PFFs.

Since the lysosome is largely responsible for the metabolism of internalized αS PFF in cells, we examined whether differences in the lysosomal content of the cells could linked to differential metabolism of internalized αS PFF in the various cell types. When the cell types used here were analyzed for the abundance of lysosome markers (Lamp-1 and Cathepsin D) (Fig. S5 D and E), microglia and astrocytes exhibit higher levels of lysosomal markers than PCN, indicating that the glial cells have higher lysosomal capacity than in PCN. Moreover, undifferentiated CLU198 cells (Fig. S5 D and E, CLU-UD) contain higher levels of lysosomal markers than the neuronally differentiated CLU198 cells (Fig. S5 D and E, CLU-Diff). These results support the view that differences in the lysosomal activity contribute to the differential metabolism of internalized αS PFF in neural cell types.

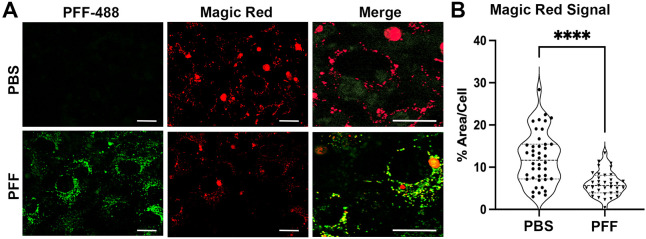

Accumulation of αS fibrils in the lysosome of neuronal cells is linked to dysfunctional lysosomes [4,10]. Thus, we tested if the accumulation of truncated αS PFF in lysosomes at early time points following PFF uptake was associated with lysosomal dysfunction. We focused on neuronal cells as the rapid degradation of αS PFF by glial cells excludes the presence of lysosomal dysfunction by αS PFF in glial cells. Differentiated CLU198 cells were treated with saline or αS PFF-AF488 and at 6- and 24-hours post-αS PFF uptake, the lysosomal function was evaluated on live cells using the Magic Red Cathepsin B activity kit (Fig. 8, Fig. S6). Our results show that both 6- and 24-hours post-PFF uptake, the levels of Cathepsin B activity were notably lower in α PFF-treated cells (Fig. 8, Fig. S6). Quantitative analysis of Magic Red Cathepsin B signal at 24 hours following PFF-uptake showed that lysosomal function, as indicated by the area occupied by the Magic Red signal per cell, was significantly lower with αS PFF treatment (Fig. 8). We also used Galectin-3 (Gal3) staining as a marker of lysosomal integrity [19]. Gal3 is normally localized diffusely in the cytosol but when the lysosome becomes permeable/damaged, Gal3 translocates into the lysosome and exhibits punctate staining. Analysis of cells treated with PBS or αS PFF shows that αS PFF treatments lead to a significant increase in Gal3 staining (Fig. S7 A, B). Finally, we analyzed lysosomal function in PCN using DQ-Red-BSA, which is targeted to lysosomes and resulting lysosomal proteolysis leads to an intense florescence signal [4]. In PCN, PFF treatment leads to a significant decrease in the DQ-Red fluorescence (Fig. S7 C, D).

Figure 8. Internalized αS PFF inhibits lysosome function in neuronal cells.

Neuronally differentiated CLU198 cells were treated with PFF-AF488, washed, and incubated for 24 h prior to confocal live cell imaging. The cells were also treated with Magic Red Cathepsin-B assay reagent for the last hour prior to imaging. (A) Representative confocal live cell images of PFF-AF488 (Green) and Magic Red (Red). Merge shows higher magnification to show details. (B) Violin Plot of % area/cell covered by Magic Red signal. The overall Magic Red signal, representing Cathepsin B activity, is significantly lower in PFF treated cells. ****p<0.0001, unpaired t-test. Bar=10 μm.

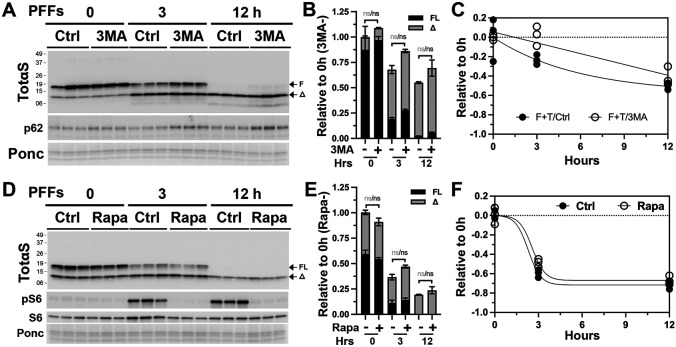

We also evaluated the involvement of other possible proteolytic machinery in the metabolism of αS PFF. Given the important relationship between the lysosomes and autophagy, we examined the possible role of autophagy in the metabolism of αS PFF. We examined the role of autophagy on αS PFF metabolism by inhibiting autophagy via the 3-methyladenine (3MA) treatment [37] (Fig. 9A-C; Fig. S8 A-D) and promoting autophagy via rapamycin treatment [38] (Fig. 9D-F; Fig. S8 E-F). 3MA treatment of differentiated CLU198 cells led to modest increases in αS levels at 3 h and 12 h following αS PFF treatment but the increase was not statistically significant (Fig. 9A-C). Non-neuronal cells treated with 3MA showed no effect on αS levels in astrocytes (Fig. S8 A and B) and a modest increase in αS levels in HEK293 cells at 12 h following PFF treatment (Fig. S8 C and D). Stimulation of autophagy by rapamycin treatment did not lead to any obvious alternations in the levels of αS following PFF treatment of differentiated CLU198 cells and non-neuronal HEK293 cells (Fig. 9 D-F; Fig. S8 E-F).

Figure 9. Autophagy is not a major factor in the metabolism of internalized αS PFF in neuronal cells.

Differentiated hippocampal CLU198 cells and were pre-treated for 4h with an autophagy inhibitor 3 methyladenine (100 mM, 3MA, A-B) or an autophagy activator rapamycin (100 ηM, Rapa, C-D). The cells were treated with 4 μg/ml αS PFF for the last 2 h of 3MA treatment and washed. Washed cells were provided with fresh media containing PBS (Control, Ctrl), 3MA or Rapa and then incubated for 0-, 3-, and 12-h before harvesting. Levels of TotαS were detected by immunoblot analysis (A, D). Ponceau S (Ponc) staining was used to verify equal protein loading. The bar (B, E) and line (C, F) graphs show the relative levels of full-length (FL) and truncated (Δ) αS levels over time. Mean±SEM; n=3. n.s., not significant.

Analysis of the levels of active lysosomal enzyme cathepsin D shows that 3MA treatment decreases active cathepsin D levels in astrocytes and HEK293 cells (Fig. S8 B and D). Thus, we believe 3MA treatment could be impacting the metabolism of αS PFF partly via induction of modest lysosomal deficit. Regardless, 3MA impacted αS PFF metabolism less than with the direct inhibition of lysosomes. Collectively, our results suggest that autophagy is a minor component in the regulation of αS PFF metabolism in neuronal cells. We also examined the potential role of the proteasome in αS PFF degradation in CLU198 and HEK-293 cells using, PS-341, a selective proteasomal inhibitor [39] (Fig. S9). We found that proteasome inhibition did not affect the metabolism of internalized αS PFF (Fig. S9). In conclusion, our studies indicate that lysosome is the major degradation machinery for the internalized αS PFFs.

Discussion

Progression of αS pathology in the brain is thought to involve cell-to-cell spreading of αS pathology where the pathogenic αS from doner neurons induces αS pathology in the neighboring neurons that internalize the pathogenic αS. In addition to neurons, glial cells can efficiently internalize extracellular αS variants released by neurons and may impact the spread of αS pathology. For example, astrocytes or microglia can attenuate the development of αS pathology in neurons by competing for the uptake of pathogenic αS [6,12,13,40]. However, most of the current studies examined the fate of exogenous αS at several hours or days following initial uptake. Thus, information about the short-term metabolism of the αS in various brain cell types is incomplete. To gain further insights about the roles of different brain cell types in the development of αS pathology, we examined how αS aggregates, in the form of αS PFF, are metabolized by various neural cells within hours of uptake rather than days. Our results show that neurons are inefficient in degrading internalized αS PFF and αS PFF stably accumulates as C-terminally truncated species. In neurons, we show that both the degradation and truncation of internalized αS PFF occurs in the endosome/lysosome compartment within minutes and hours following initial internalization of αS PFF. Moreover, truncation and stable accumulation of internalized αS PFF occurs in both primary cultured neurons as well as neuronal cell lines. Significantly, in neuronal cell lines (CLU-198 and SH-SY5Y), stable accumulation of truncated αS PFF is selectively associated with neuronal differentiation as undifferentiated cells rapidly degrade internalized αS PFF. Similarly, astrocytes and microglia rapidly degrade internalized αS PFF within 6-8 hours while αS PFF accumulates as truncated species in oligodendrocytes. Epitope mapping of the internalized αS PFF shows that the major 10 kDa truncated species, αS10, retains the N-terminal epitopes but presumably missing ~40 amino acids from the C-terminal region. We also show that the lysosome is a major organelle responsible for the degradation of internalized αS PFF as inhibition of lysosomes significantly increased accumulation of αS PFF in all cell types.

We showed that a significant fraction of αS is normally truncated at the C-terminal region and the C-terminally truncated αS can promote αS aggregation [17]. Moreover, the abundance of C-terminally truncated αS is increased in PD cases as well as in the αS aggregates in vivo [17]. However, the current report indicates that the truncation of internalized αS PFF is different than the truncation of αS expressed in cells or αS aggregates extracted from human and mouse cells/brain. While ~5-25% of endogenously expressed αS monomers accumulate as C-terminal truncated forms [17], internalized exogenous αS monomer is efficiently degraded without any accumulation of truncated αS. Further, αS aggregates extracted from mouse or human brains are partially truncated (~25-50%) [17], while virtually 100% of internalized αS PFF are truncated. Similarly, analysis of lysosomes isolated from the brains of a TgA53T mouse line shows that aSFL is more abundant than the truncated αS [34]. Direct comparison of truncated variants in αS PFF treated neurons with the αS aggregates extracted from the human PD cases and the TgA53T model show that, with the in vivo derived αS aggregates, the major C-terminally truncated species resolve at ~12 kDa [17], rather than ~10 kDa seen with αS PFF (Fig. 5). While we have not defined actual site of αS truncation, other studies have shown that several lysosomal proteases can truncate αS at several C-terminal residues [34], including Glu114 and Asn103 [33,34,41]. Interestingly, cleavage at Glu114 is resistant to Cathepsin inhibition [41], and cleavage at Asn103, while catalyzed by asparagine endopeptidase (AEP), is independent of lysosomal pH [42]. Our study differs from some of these studies as we observe dramatic differences in αS PFF metabolism in HEK293 cells used by Quintin and colleagues [41] and we were not able to document truncation at Asn103 using commercially available antibody (N103, Millipore-Sigma ABN2260; data not shown). Significantly, while astrocytes and microglia can rapidly degrade αS PFF without accumulation of αSΔ, oligodendrocytes resemble neurons as both cell types accumulate truncated αS10. Thus, C-terminal truncation and accumulation of exogenous αS PFF is a common feature of the cell types that are known to develop αS aggregates in human α-synucleinopathies.

Significantly, internalized αS PFF, even when extensively truncated, remains insoluble for at least 7 days, indicating that αS PFF remains aggregated in neurons for an extended period. The increased stability of the αS PFF in neurons may be because internalized αS PFF causes lysosomal dysfunction. However, this effect must not be a global lysosomal deficit but at an individual lysosome level since even very low levels of αS PFF are truncated and remain stable for an extended period. This result also indicates that even with the internalization of small amounts αS PFF by neurons, there is an extended timeframe for the internalized αS PFF to seed αS aggregation.

Collectively, we show that under normal conditions, any exogenous αS monomers are rapidly metabolized by all brain cell types but αS PFF, representing αS aggregates, are rapidly metabolized by glial cells but not by neurons. Our results suggest that studies on the cellular effects of αS PFF will need to consider the cell types used. We also predict that, if αS oligomers/aggregates are released extracellularly, astrocytes and microglia will efficiently remove the αS oligomers/aggregates under normal conditions, preventing significant transmission of αS oligomers/aggregates to neighboring neurons. However, under conditions that may lead to reduced αS uptake or lysosomal dysfunction, such as aging or increased inflammation, reduced metabolism of exogenous αS by glial cells likely promotes neuronal uptake of αS oligomers/aggregates and subsequent development of αS pathology.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

We thank Drs. Mohammad Abdur Rashid and Balvindar Singh for the early observations leading to the current report. We also thank Mr. Hector Martell Martinez for help with glial cultures.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to MKL: R01-NS086074, R01-NS092093, and the Aligning Science Across Parkinson’s (ASAP-000592/ASAP-024407) grant administered through the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research (MJFF).

Abbreviations:

- Baf A1

bafilomycin A1

- DMEM

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium

- DMSO

Dimethyl sulfoxide

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- LC3

microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3

- NAC domain

non-amyloidal component

- PD

Parkinson’s diseases

- p62 (SQSTM1)

sequestosome 1

- PFF

αS pre-formed-fibril

- PCN

primary cortical neuron

- PMG

primary microglia

- αS

α-synuclein

- αSΔC

C-terminally truncated αS

- FL

full-length

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

The data and materials are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- [1].Spillantini MG, Schmidt ML, Lee VM, et al. Alpha-synuclein in Lewy bodies. Nature. 1997. Aug 28;388(6645):839–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Cremades N, Cohen SI, Deas E, et al. Direct observation of the interconversion of normal and toxic forms of alpha-synuclein. Cell. 2012. May 25;149(5):1048–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Bengoa-Vergniory N, Roberts RF, Wade-Martins R, et al. Alpha-synuclein oligomers: a new hope. Acta Neuropathol. 2017. Dec;134(6):819–838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Senol AD, Samarani M, Syan S, et al. alpha-Synuclein fibrils subvert lysosome structure and function for the propagation of protein misfolding between cells through tunneling nanotubes. Plos Biol. 2021. Jul;19(7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Bae EJ, Yang NY, Song M, et al. Glucocerebrosidase depletion enhances cell-to-cell transmission of alpha-synuclein. Nat Commun. 2014. Aug 26;5:4755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Loria F, Vargas JY, Bousset L, et al. alpha-Synuclein transfer between neurons and astrocytes indicates that astrocytes play a role in degradation rather than in spreading. Acta Neuropathol. 2017. Nov;134(5):789–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Chung HK, Ho HA, Perez-Acuna D, et al. Modeling alpha-Synuclein Propagation with Preformed Fibril Injections. J Mov Disord. 2019. Sep;12(3):139–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Volpicelli-Daley LA, Luk KC, Patel TP, et al. Exogenous alpha-synuclein fibrils induce Lewy body pathology leading to synaptic dysfunction and neuron death. Neuron. 2011. Oct 6;72(1):57–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Hoffmann AC, Minakaki G, Menges S, et al. Extracellular aggregated alpha synuclein primarily triggers lysosomal dysfunction in neural cells prevented by trehalose. Scientific reports. 2019. Jan 24;9(1):544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Karim MR, Liao EE, Kim J, et al. alpha-Synucleinopathy associated c-Abl activation causes p53-dependent autophagy impairment. Mol Neurodegener. 2020. Apr 16;15(1):27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Poehler AM, Xiang W, Spitzer P, et al. Autophagy modulates SNCA/alpha-synuclein release, thereby generating a hostile microenvironment. Autophagy. 2014;10(12):2171–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Scheiblich H, Dansokho C, Mercan D, et al. Microglia jointly degrade fibrillar alpha-synuclein cargo by distribution through tunneling nanotubes. Cell. 2021. Sep 30;184(20):5089–5106 e21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Choi I, Zhang Y, Seegobin SP, et al. Microglia clear neuron-released alpha-synuclein via selective autophagy and prevent neurodegeneration. Nat Commun. 2020. Mar 13;11(1):1386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Vermilyea SC, Christensen A, Meints J, et al. Loss of tau expression attenuates neurodegeneration associated with alpha-synucleinopathy. Transl Neurodegener. 2022. Jul 1;11(1):34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Nanclares C, Poynter J, Martell-Martinez HA, et al. Dysregulation of astrocytic Ca(2+) signaling and gliotransmitter release in mouse models of alpha-synucleinopathies. Acta Neuropathol. 2023. May;145(5):597–610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Volpicelli-Daley LA, Luk KC, Lee VM. Addition of exogenous alpha-synuclein preformed fibrils to primary neuronal cultures to seed recruitment of endogenous alpha-synuclein to Lewy body and Lewy neurite-like aggregates [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural]. Nat Protoc. 2014. Sep;9(9):2135–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Li W, West N, Colla E, et al. Aggregation promoting C-terminal truncation of alpha-synuclein is a normal cellular process and is enhanced by the familial Parkinson's disease-linked mutations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005. Feb 8;102(6):2162–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Singh B, Covelo A, Martell-Martinez H, et al. Tau is required for progressive synaptic and memory deficits in a transgenic mouse model of alpha-synucleinopathy. Acta Neuropathol. 2019. Jun 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Aits S. Methods to Detect Loss of Lysosomal Membrane Integrity. Methods Mol Biol. 2019;1880:315–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Li W, Lesuisse C, Xu Y, et al. Stabilization of alpha-synuclein protein with aging and familial parkinson's disease-linked A53T mutation. J Neurosci. 2004. Aug 18;24(33):7400–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Gingerich S, Kim GL, Chalmers JA, et al. Estrogen receptor alpha and G-protein coupled receptor 30 mediate the neuroprotective effects of 17beta-estradiol in novel murine hippocampal cell models. Neuroscience. 2010. Sep 29;170(1):54–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Mahul-Mellier AL, Burtscher J, Maharjan N, et al. The process of Lewy body formation, rather than simply alpha-synuclein fibrillization, is one of the major drivers of neurodegeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020. Mar 3;117(9):4971–4982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Peng C, Gathagan RJ, Covell DJ, et al. Cellular milieu imparts distinct pathological alpha-synuclein strains in alpha-synucleinopathies. Nature. 2018. May;557(7706):558–563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Reddy K, Dieriks BV. Multiple system atrophy: alpha-Synuclein strains at the neuron-oligodendrocyte crossroad. Mol Neurodegener. 2022. Nov 26;17(1):77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Halliday GM, Holton JL, Revesz T, et al. Neuropathology underlying clinical variability in patients with synucleinopathies [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't Review]. Acta Neuropathol. 2011. Aug;122(2):187–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Luth ES, Stavrovskaya IG, Bartels T, et al. Soluble, prefibrillar alpha-synuclein oligomers promote complex I-dependent, Ca2+-induced mitochondrial dysfunction. J Biol Chem. 2014. Aug 1;289(31):21490–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Perrin RJ, Payton JE, Barnett DH, et al. Epitope mapping and specificity of the anti-alpha-synuclein monoclonal antibody Syn-1 in mouse brain and cultured cell lines. Neurosci Lett. 2003. Oct 2;349(2):133–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Sorrentino ZA, Vijayaraghavan N, Gorion KM, et al. Physiological C-terminal truncation of alpha-synuclein potentiates the prion-like formation of pathological inclusions. J Biol Chem. 2018. Dec 7;293(49):18914–18932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Sorrentino ZA, Giasson BI. The emerging role of alpha-synuclein truncation in aggregation and disease. J Biol Chem. 2020. Jul 24;295(30):10224–10244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Masaracchia C, Hnida M, Gerhardt E, et al. Membrane binding, internalization, and sorting of alpha-synuclein in the cell. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2018. Aug 14;6(1):79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Rodriguez L, Marano MM, Tandon A. Import and Export of Misfolded alpha-Synuclein. Front Neurosci. 2018;12:344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Burbidge K, Rademacher DJ, Mattick J, et al. LGALS3 (galectin 3) mediates an unconventional secretion of SNCA/alpha-synuclein in response to lysosomal membrane damage by the autophagic-lysosomal pathway in human midbrain dopamine neurons. Autophagy. 2022. May;18(5):1020–1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Zhang Z, Kang SS, Liu X, et al. Asparagine endopeptidase cleaves alpha-synuclein and mediates pathologic activities in Parkinson's disease. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2017. Aug;24(8):632–642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].McGlinchey RP, Lacy SM, Huffer KE, et al. C-terminal alpha-synuclein truncations are linked to cysteine cathepsin activity in Parkinson's disease. J Biol Chem. 2019. Jun 21;294(25):9973–9984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Lie PPY, Nixon RA. Lysosome trafficking and signaling in health and neurodegenerative diseases. Neurobiol Dis. 2019. Feb;122:94–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Song Q, Meng B, Xu H, et al. The emerging roles of vacuolar-type ATPase-dependent Lysosomal acidification in neurodegenerative diseases. Transl Neurodegener. 2020. May 11;9(1):17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Wu YT, Tan HL, Shui G, et al. Dual role of 3-methyladenine in modulation of autophagy via different temporal patterns of inhibition on class I and III phosphoinositide 3-kinase. J Biol Chem. 2010. Apr 2;285(14):10850–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Sarkar S, Ravikumar B, Floto RA, et al. Rapamycin and mTOR-independent autophagy inducers ameliorate toxicity of polyglutamine-expanded huntingtin and related proteinopathies. Cell Death Differ. 2009. Jan;16(1):46–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Bazzaro M, Lin Z, Santillan A, et al. Ubiquitin proteasome system stress underlies synergistic killing of ovarian cancer cells by bortezomib and a novel HDAC6 inhibitor. Clin Cancer Res. 2008. Nov 15;14(22):7340–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Tsunemi T, Ishiguro Y, Yoroisaka A, et al. Astrocytes Protect Human Dopaminergic Neurons from alpha-Synuclein Accumulation and Propagation. J Neurosci. 2020. Nov 4;40(45):8618–8628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Quintin S, Lloyd GM, Paterno G, et al. Cellular processing of alpha-synuclein fibrils results in distinct physiological C-terminal truncations with a major cleavage site at residue Glu 114. J Biol Chem. 2023. Jul;299(7):104912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Kang SS, Ahn EH, Zhang Z, et al. alpha-Synuclein stimulation of monoamine oxidase-B and legumain protease mediates the pathology of Parkinson's disease. EMBO J. 2018. Jun 15;37(12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.